Download the full program as PDF - Fashion Film Festival

Download the full program as PDF - Fashion Film Festival

Download the full program as PDF - Fashion Film Festival

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

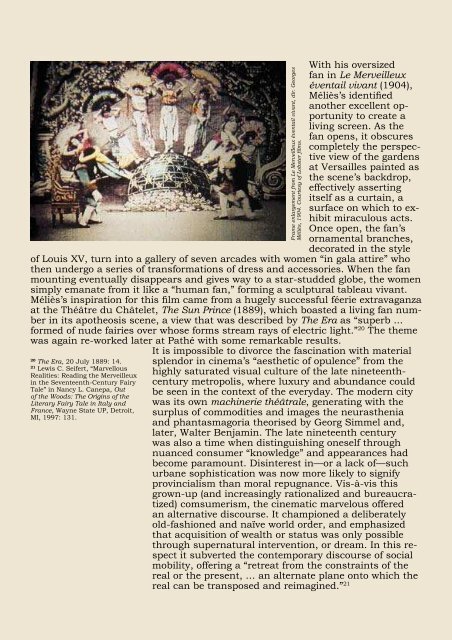

With his oversized<br />

fan in Le Merveilleux<br />

éventail vivant (1904),<br />

Méliès’s identified<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r excellent opportunity<br />

to create a<br />

living screen. As <strong>the</strong><br />

fan opens, it obscures<br />

completely <strong>the</strong> perspective<br />

view of <strong>the</strong> gardens<br />

at Versailles painted <strong>as</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> scene’s backdrop,<br />

effectively <strong>as</strong>serting<br />

itself <strong>as</strong> a curtain, a<br />

surface on which to exhibit<br />

miraculous acts.<br />

Once open, <strong>the</strong> fan’s<br />

ornamental branches,<br />

decorated in <strong>the</strong> style<br />

of Louis XV, turn into a gallery of seven arcades with women “in gala attire” who<br />

<strong>the</strong>n undergo a series of transformations of dress and accessories. When <strong>the</strong> fan<br />

mounting eventually disappears and gives way to a star-studded globe, <strong>the</strong> women<br />

simply emanate from it like a “human fan,” forming a sculptural tableau vivant.<br />

Méliès’s inspiration for this film came from a hugely successful féerie extravaganza<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Théâtre du Châtelet, The Sun Prince (1889), which bo<strong>as</strong>ted a living fan number<br />

in its apo<strong>the</strong>osis scene, a view that w<strong>as</strong> described by The Era <strong>as</strong> “superb ...<br />

formed of nude fairies over whose forms stream rays of electric light.” 20 The <strong>the</strong>me<br />

w<strong>as</strong> again re-worked later at Pathé with some remarkable results.<br />

It is impossible to divorce <strong>the</strong> f<strong>as</strong>cination with material<br />

splendor in cinema’s “aes<strong>the</strong>tic of opulence” from <strong>the</strong><br />

highly saturated visual culture of <strong>the</strong> late nineteenthcentury<br />

metropolis, where luxury and abundance could<br />

be seen in <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> everyday. The modern city<br />

w<strong>as</strong> its own machinerie théâtrale, generating with <strong>the</strong><br />

surplus of commodities and images <strong>the</strong> neur<strong>as</strong><strong>the</strong>nia<br />

and phant<strong>as</strong>magoria <strong>the</strong>orised by Georg Simmel and,<br />

later, Walter Benjamin. The late nineteenth century<br />

w<strong>as</strong> also a time when distinguishing oneself through<br />

nuanced consumer “knowledge” and appearances had<br />

become paramount. Disinterest in—or a lack of—such<br />

urbane sophistication w<strong>as</strong> now more likely to signify<br />

provincialism than moral repugnance. Vis-à-vis this<br />

grown-up (and incre<strong>as</strong>ingly rationalized and bureaucratized)<br />

comsumerism, <strong>the</strong> cinematic marvelous offered<br />

an alternative discourse. It championed a deliberately<br />

old-f<strong>as</strong>hioned and naïve world order, and emph<strong>as</strong>ized<br />

that acquisition of wealth or status w<strong>as</strong> only possible<br />

through supernatural intervention, or dream. In this respect<br />

it subverted <strong>the</strong> contemporary discourse of social<br />

mobility, offering a “retreat from <strong>the</strong> constraints of <strong>the</strong><br />

real or <strong>the</strong> present, … an alternate plane onto which <strong>the</strong><br />

real can be transposed and reimagined.” 21<br />

Frame enlargement from Le Merveilleux éventail vivant, dir. Georges<br />

Méliès, 1904. Courtesy of Lobster films.<br />

engenDering FAust:<br />

tHe veileD lADY in nino oxiliA’s<br />

RApSODIA sAtAnicA<br />

Eugenia paulicelli<br />

Rapsodia satanica, by <strong>the</strong> Turin-b<strong>as</strong>ed writer and director<br />

Nino Oxilia, is a true m<strong>as</strong>terpiece whose value deserves to be recognized and<br />

positioned in <strong>the</strong> wider context of <strong>the</strong> history of cinema in Italy and beyond. It is<br />

especially crucial to see how this early Italian film can be re-read today through<br />

<strong>the</strong> lens of dress and f<strong>as</strong>hion so <strong>as</strong> to capture <strong>the</strong> philosophical underpinnings of<br />

Oxilia’s reinterpretation of <strong>the</strong> Faust legend, its gender implications, and its aes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

folding and unfolding of his “dance of human p<strong>as</strong>sions.” 1 Unlike o<strong>the</strong>r versions<br />

of Faustian narratives, in Rapsodia it is an elderly woman, Alba d’Oltrevita<br />

(whose name we could translate <strong>as</strong> Dawn beyond Life), played by <strong>the</strong> Italian diva<br />

Lyda Borelli, who makes <strong>the</strong> pact with <strong>the</strong> Devil. The price she is <strong>as</strong>ked to pay to<br />

regain her beauty and youth is to give up love. Youth and beauty are exchanged<br />

for a life devoid of emotion, p<strong>as</strong>sion, and sensuality—almost a contradiction in<br />

terms. This is especially so because in <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> film, Alba unfolds herself<br />

into younger skin and becomes a femme fatale.<br />

Rapsodia satanica foregrounds <strong>the</strong>mes of <strong>the</strong> fragility of<br />

human actions, emotions, <strong>the</strong> impossibility of divorcing love from youth and life,<br />

<strong>the</strong> transience of human existence and actions and, above all, time and its inherent<br />

slipperiness. All are <strong>the</strong>mes quintessential to this film and perhaps also to<br />

film in general, especially at <strong>the</strong> time of experimentation and advancement in <strong>the</strong><br />

arts and sciences in which Rapsodia w<strong>as</strong> made. And this is ano<strong>the</strong>r re<strong>as</strong>on why<br />

Oxilia’s film is so rich. Time is embedded in <strong>the</strong> cinematic machine in its kineaes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

multi-dimensionality. The composer Pietro M<strong>as</strong>cagni wrote <strong>the</strong> score for <strong>the</strong><br />

film, signalling artistic collaboration between <strong>the</strong> relatively new cinematographic<br />

art and <strong>the</strong> world of high art, <strong>the</strong>ater and opera. Rapsodia is a big production<br />

conceived <strong>as</strong> an opera totale of <strong>the</strong> Rome-b<strong>as</strong>ed production house, Cines. In its<br />

very title, <strong>the</strong> film offers itself <strong>as</strong> a challenge to <strong>the</strong> tradition of <strong>the</strong> art of storytelling<br />

in <strong>the</strong> age of mechanical reproduction.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> c<strong>as</strong>tle of illusions where Alba lives, anything can<br />

happen. It is <strong>as</strong> if <strong>the</strong> c<strong>as</strong>tle itself were a movie <strong>the</strong>ater<br />

in which acts of magic and illusion are performed on<br />

<strong>the</strong> screen, like a painting of Mephisto coming to life<br />

and jumping into <strong>the</strong> room where Alba sits, reaching<br />

out not only to her but also to <strong>the</strong> spectator. There is a witty cinematic allusion<br />

to technology and <strong>the</strong> transformation of <strong>the</strong> self that is incarnated on screen by<br />

<strong>the</strong> performance of <strong>the</strong> diva especially, <strong>as</strong> she changes through dress and movement.<br />

However, this metamorphosis from one scenario to ano<strong>the</strong>r, through <strong>the</strong><br />

film’s rhythms and interruptions, does not prevent her inevitable death. It only<br />

postpones it. The dances and m<strong>as</strong>querades defer death; <strong>the</strong>re can be no salvation<br />

for Alba. The price she pays for youth is loneliness of <strong>the</strong> heart. Alba appears<br />

<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> veiled lady, and <strong>as</strong> such she is both <strong>the</strong> author and <strong>the</strong> vehicle of<br />

transformation. The veil, in fact, accompanies all her rituals of dressing, redressing<br />

and addressing; a piece of fabric covers and uncovers, envelops and exposes<br />

her body and her face. It is Alba’s habitus.<br />

As a recurrent element in <strong>the</strong> whole film, <strong>the</strong> veil is also<br />

what binds <strong>the</strong> several threads of Rapsodia toge<strong>the</strong>r in its narrative and nonnarrative<br />

moments. But Alba’s is a veil that is never stitched. In Oxilia’s film, <strong>the</strong><br />

binding fabric that holds toge<strong>the</strong>r its different acts always flows, never losing its