Stalking : policing and prosecuting practices in three Australian ...

Stalking : policing and prosecuting practices in three Australian ...

Stalking : policing and prosecuting practices in three Australian ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

typologies (see Table 1). For<br />

example, Zona et al.’s (1998)<br />

research, which is predom<strong>in</strong>antly<br />

concerned with psychiatric<br />

classification, divides two of these<br />

classifications, (simple<br />

obsessional <strong>and</strong> love obsessional)<br />

on the basis of the relationship<br />

between the offender <strong>and</strong> victim.<br />

Similarly, Mullen et al. (2000),<br />

Harmon et al. (1998) <strong>and</strong> Wright<br />

et al. (1996) utilise a mixture of<br />

motivations <strong>and</strong> psychiatric<br />

characteristics <strong>in</strong> the<br />

development of their typologies.<br />

Specific examples of<br />

categorisations of stalk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude Harmon, Rosner <strong>and</strong><br />

Owens (1995) who developed a<br />

classification scheme for the<br />

offenders along two axes: “one<br />

relat<strong>in</strong>g to the nature of the<br />

attachment between the<br />

defendant <strong>and</strong> the object of their<br />

attentions, <strong>and</strong> another relat<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

the nature, if any of the prior<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction between them”<br />

(Harmon et al. 1995, p. 189).<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Institute of Crim<strong>in</strong>ology<br />

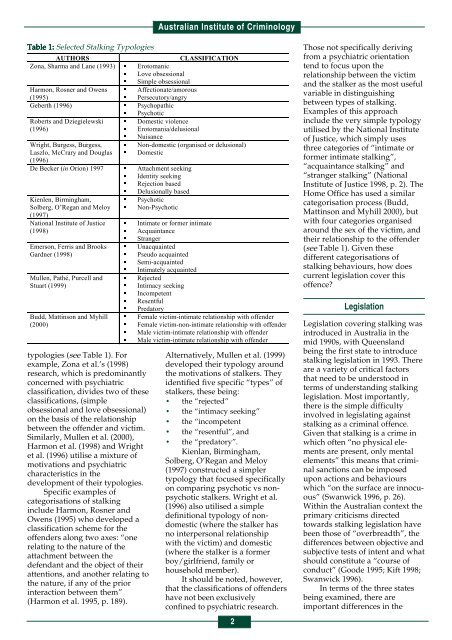

Table Table 1: 1: Selected <strong>Stalk<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Typologies<br />

AUTHORS CLASSIFICATION<br />

Zona, Sharma <strong>and</strong> Lane (1993) Erotomanic<br />

Love obsessional<br />

Simple obsessional<br />

Harmon, Rosner <strong>and</strong> Owens Affectionate/amorous<br />

(1995)<br />

Persecutory/angry<br />

Geberth (1996) Psychopathic<br />

Psychotic<br />

Roberts <strong>and</strong> Dziegielewski Domestic violence<br />

(1996)<br />

Erotomania/delusional<br />

Nuisance<br />

Wright, Burgess, Burgess, Non-domestic (organised or delusional)<br />

Laszlo, McCrary <strong>and</strong> Douglas<br />

(1996)<br />

Domestic<br />

De Becker (<strong>in</strong> Orion) 1997 Attachment seek<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Identity seek<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Rejection based<br />

Delusionally based<br />

Kienlen, Birm<strong>in</strong>gham,<br />

Psychotic<br />

Solberg, O’Regan <strong>and</strong> Meloy<br />

(1997)<br />

Non-Psychotic<br />

National Institute of Justice Intimate or former <strong>in</strong>timate<br />

(1998)<br />

Acqua<strong>in</strong>tance<br />

Stranger<br />

Emerson, Ferris <strong>and</strong> Brooks Unacqua<strong>in</strong>ted<br />

Gardner (1998)<br />

Pseudo acqua<strong>in</strong>ted<br />

Semi-acqua<strong>in</strong>ted<br />

Intimately acqua<strong>in</strong>ted<br />

Mullen, Pathé, Purcell <strong>and</strong> Rejected<br />

Stuart (1999)<br />

Intimacy seek<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Incompetent<br />

Resentful<br />

Predatory<br />

Budd, Matt<strong>in</strong>son <strong>and</strong> Myhill Female victim-<strong>in</strong>timate relationship with offender<br />

(2000)<br />

Female victim-non-<strong>in</strong>timate relationship with offender<br />

Male victim-<strong>in</strong>timate relationship with offender<br />

Male victim-<strong>in</strong>timate relationship with offender<br />

Alternatively, Mullen et al. (1999)<br />

developed their typology around<br />

the motivations of stalkers. They<br />

identified five specific “types” of<br />

stalkers, these be<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

the “rejected”<br />

the “<strong>in</strong>timacy seek<strong>in</strong>g”<br />

the “<strong>in</strong>competent<br />

the “resentful”, <strong>and</strong><br />

the “predatory”.<br />

Kienlan, Birm<strong>in</strong>gham,<br />

Solberg, O’Regan <strong>and</strong> Meloy<br />

(1997) constructed a simpler<br />

typology that focused specifically<br />

on compar<strong>in</strong>g psychotic vs nonpsychotic<br />

stalkers. Wright et al.<br />

(1996) also utilised a simple<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itional typology of nondomestic<br />

(where the stalker has<br />

no <strong>in</strong>terpersonal relationship<br />

with the victim) <strong>and</strong> domestic<br />

(where the stalker is a former<br />

boy/girlfriend, family or<br />

household member).<br />

It should be noted, however,<br />

that the classifications of offenders<br />

have not been exclusively<br />

conf<strong>in</strong>ed to psychiatric research.<br />

2<br />

Those not specifically deriv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

from a psychiatric orientation<br />

tend to focus upon the<br />

relationship between the victim<br />

<strong>and</strong> the stalker as the most useful<br />

variable <strong>in</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

between types of stalk<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Examples of this approach<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude the very simple typology<br />

utilised by the National Institute<br />

of Justice, which simply uses<br />

<strong>three</strong> categories of “<strong>in</strong>timate or<br />

former <strong>in</strong>timate stalk<strong>in</strong>g”,<br />

“acqua<strong>in</strong>tance stalk<strong>in</strong>g” <strong>and</strong><br />

“stranger stalk<strong>in</strong>g” (National<br />

Institute of Justice 1998, p. 2). The<br />

Home Office has used a similar<br />

categorisation process (Budd,<br />

Matt<strong>in</strong>son <strong>and</strong> Myhill 2000), but<br />

with four categories organised<br />

around the sex of the victim, <strong>and</strong><br />

their relationship to the offender<br />

(see Table 1). Given these<br />

different categorisations of<br />

stalk<strong>in</strong>g behaviours, how does<br />

current legislation cover this<br />

offence?<br />

Legislation<br />

Legislation cover<strong>in</strong>g stalk<strong>in</strong>g was<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> Australia <strong>in</strong> the<br />

mid 1990s, with Queensl<strong>and</strong><br />

be<strong>in</strong>g the first state to <strong>in</strong>troduce<br />

stalk<strong>in</strong>g legislation <strong>in</strong> 1993. There<br />

are a variety of critical factors<br />

that need to be understood <strong>in</strong><br />

terms of underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g stalk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

legislation. Most importantly,<br />

there is the simple difficulty<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> legislat<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

stalk<strong>in</strong>g as a crim<strong>in</strong>al offence.<br />

Given that stalk<strong>in</strong>g is a crime <strong>in</strong><br />

which often “no physical elements<br />

are present, only mental<br />

elements” this means that crim<strong>in</strong>al<br />

sanctions can be imposed<br />

upon actions <strong>and</strong> behaviours<br />

which “on the surface are <strong>in</strong>nocuous”<br />

(Swanwick 1996, p. 26).<br />

With<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Australian</strong> context the<br />

primary criticisms directed<br />

towards stalk<strong>in</strong>g legislation have<br />

been those of “overbreadth”, the<br />

differences between objective <strong>and</strong><br />

subjective tests of <strong>in</strong>tent <strong>and</strong> what<br />

should constitute a “course of<br />

conduct” (Goode 1995; Kift 1998;<br />

Swanwick 1996).<br />

In terms of the <strong>three</strong> states<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g exam<strong>in</strong>ed, there are<br />

important differences <strong>in</strong> the