Practical Approach to the Pathologic Diagnosis of Gastritis

Practical Approach to the Pathologic Diagnosis of Gastritis

Practical Approach to the Pathologic Diagnosis of Gastritis

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Practical</strong> <strong>Approach</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong><br />

● Context.—Most types <strong>of</strong> gastritis can be diagnosed on<br />

hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin stains. The most common type <strong>of</strong> chronic<br />

gastritis is Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Reactive or<br />

chemical gastropathy, which is <strong>of</strong>ten associated with nonsteroidal<br />

anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry drug use or bile reflux, is common<br />

in most practices. The diagnosis <strong>of</strong> atrophic gastritis<br />

can be challenging if few biopsy samples are available and<br />

if <strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsies in <strong>the</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach is not known,<br />

such as when random biopsies are sampled in one jar. If<br />

<strong>the</strong> biopsy site is not known, immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains,<br />

such as a combination <strong>of</strong> synap<strong>to</strong>physin and gastrin, are<br />

useful in establishing <strong>the</strong> biopsy location.<br />

Objective.—To demonstrate a practical approach <strong>to</strong><br />

achieving a pathologic diagnosis <strong>of</strong> gastritis by evaluating<br />

a limited number <strong>of</strong> features in mucosal biopsies.<br />

Data Source.—In this article, we present several repre-<br />

<strong>Gastritis</strong> refers <strong>to</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> diseases characterized by<br />

inflammation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric mucosa. His<strong>to</strong>logic examination<br />

<strong>of</strong> gastric mucosal biopsies is necessary <strong>to</strong> establish<br />

a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> gastritis. In clinical practice, <strong>the</strong> role<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pathologist who evaluates a gastric biopsy for gastritis<br />

is <strong>to</strong> find <strong>the</strong> cause <strong>of</strong> gastritis because that will provide<br />

direct targets <strong>to</strong>ward which <strong>the</strong>rapeutic measures can<br />

be directed. An etiologic classification <strong>of</strong> gastritis is presented<br />

at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> this section. Comprehensive reviews<br />

<strong>of</strong> gastritis have been published. 1,2,3 The goal <strong>of</strong> this article<br />

is <strong>to</strong> present a practical approach <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

most common types <strong>of</strong> gastritis encountered in a large<br />

practice <strong>of</strong> gastrointestinal pathology. The reader will be<br />

presented several cases representative <strong>of</strong> typical forms <strong>of</strong><br />

gastritis; for each case, <strong>the</strong> reader will be prompted<br />

through a series <strong>of</strong> questions <strong>to</strong> examine <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>logic<br />

features <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa, leading <strong>to</strong> a pattern <strong>of</strong> answers<br />

and <strong>to</strong> a final diagnosis.<br />

The first question is aimed at determining whe<strong>the</strong>r or<br />

not <strong>the</strong>re are features <strong>of</strong> chronic or acute (active) gastritis<br />

Accepted for publication January 10, 2008.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Pathology and Labora<strong>to</strong>ry Medicine, Hospital<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.<br />

The authors have no relevant financial interest in <strong>the</strong> products or<br />

companies described in this article.<br />

Presented in part at <strong>the</strong> 47th Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hous<strong>to</strong>n Society<br />

<strong>of</strong> Clinical Pathologists, Hous<strong>to</strong>n, Tex, April 21, 2007.<br />

Reprints: An<strong>to</strong>nia R. Sepulveda, MD, PhD, Department <strong>of</strong> Pathology<br />

and Labora<strong>to</strong>ry Medicine, University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce St,<br />

Founders Six, Philadelphia, PA 19104 (e-mail: asepu@mail.med.<br />

upenn.edu).<br />

An<strong>to</strong>nia R. Sepulveda, MD, PhD; Madhavi Patil, MD<br />

sentative gastric biopsy cases from a gastrointestinal pathology<br />

practice <strong>to</strong> demonstrate <strong>the</strong> practical application<br />

<strong>of</strong> basic his<strong>to</strong>pathologic methods for <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> gastritis.<br />

Conclusions.—Limited ancillary tests are usually required<br />

for a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> gastritis. In some cases, special<br />

stains, such as acid-fast stains, and immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stains, such as for H pylori and viruses, can be useful. Helicobacter<br />

pylori immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains can particularly<br />

contribute (1) when moderate <strong>to</strong> severe, chronic gastritis<br />

or active gastritis is present but no Helicobacter organisms<br />

are identified upon hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin stain; (2)<br />

when extensive intestinal metaplasia is present; and (3) in<br />

follow-up biopsies, after antibiotic treatment for H pylori.<br />

(Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1586–1593)<br />

present. If <strong>the</strong> biopsy shows chronic gastritis, <strong>the</strong> following<br />

questions should be posed:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis present? Lymphocytic<br />

and plasmacytic inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry reaction indicates<br />

chronic gastritis.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? The presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> neutrophils indicate active gastritis.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter?<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re glandular atrophy? Is intestinal metaplasia<br />

present?<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions (predominantly in<br />

<strong>the</strong> oxyntic mucosa <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> body and fundus, predominantly<br />

in antrum, or involving both locations)?<br />

6. Are <strong>the</strong>re special features (such as granulomas, foveolar<br />

hyperplasia, viral inclusions)?<br />

7. What ancillary studies are indicated, and what are<br />

<strong>the</strong> results?<br />

TYPES OF CHRONIC GASTRITIS<br />

Infectious <strong>Gastritis</strong><br />

Helicobacter pylori infection is <strong>the</strong> most common cause <strong>of</strong><br />

chronic gastritis. O<strong>the</strong>r forms <strong>of</strong> infectious gastritis include<br />

<strong>the</strong> following: Helicobacter heilmannii–associated gastritis;<br />

granuloma<strong>to</strong>us gastritis associated with gastric infections<br />

in mycobacteriosis, syphilis, his<strong>to</strong>plasmosis, mucormycosis,<br />

South American blas<strong>to</strong>mycosis, anisakiasis or anisakidosis;<br />

chronic gastritis associated with parasitic infections;<br />

and viral infections, such as cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus and<br />

herpesvirus infection.<br />

1586 Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil

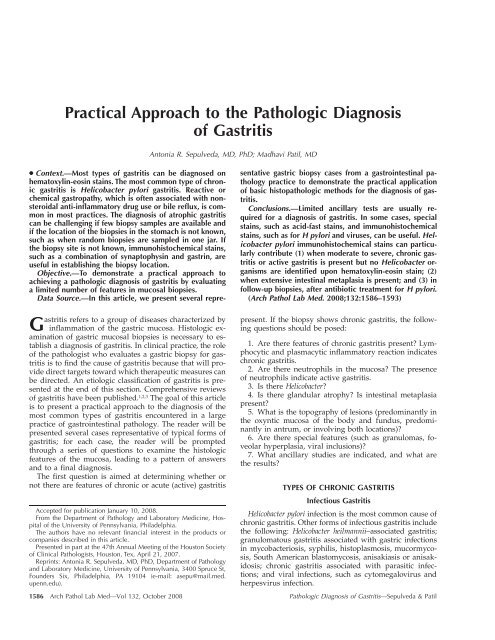

Figure 1. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic active gastritis. A,<br />

Chronic inflammation oriented <strong>to</strong>ward <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa. Neutrophils<br />

cannot be seen at this magnification (original magnification<br />

10) but were identified with high power (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin stain). B,<br />

Circled area shows H pylori organisms within <strong>the</strong> mucus layer close<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> gastric epi<strong>the</strong>lial cells (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original<br />

magnification 40). C, Gastric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin,<br />

original magnification 20).<br />

Noninfectious <strong>Gastritis</strong><br />

Noninfectious gastritis is associated with au<strong>to</strong>immune<br />

gastritis; reactive or chemical gastropathy, usually related<br />

<strong>to</strong> chronic bile reflux or nonsteroidal anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

drug (NSAID) intake; uremic gastropathy; noninfectious<br />

granuloma<strong>to</strong>us gastritis; lymphocytic gastritis, including<br />

gastritis associated with celiac disease; eosinophilic gastritis;<br />

radiation injury <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach; graft-versus-host<br />

disease; ischemic gastritis; and gastritis secondary <strong>to</strong> chemo<strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

Many cases <strong>of</strong> gastritis are <strong>of</strong> undetermined cause and<br />

present as chronic, inactive gastritis with various degrees<br />

<strong>of</strong> severity. 3<br />

TYPES OF ACUTE GASTRITIS<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forms <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis may present with<br />

an acute form, with progression <strong>to</strong> chronic gastritis because<br />

<strong>of</strong> persisting injury or sequelae. This is <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong><br />

gastritis associated with long-term intake <strong>of</strong> aspirin and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r NSAIDs and bile reflux in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach; excessive<br />

alcohol consumption; heavy smoking; cancer chemo<strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

drugs and radiation; acids and alkali in suicide<br />

attempts; uremia; severe stress (trauma, burns, surgery);<br />

ischemia and shock; systemic infections; mechanical trauma,<br />

such as intubation associated mucosal lesions; and viral<br />

infections.<br />

Case 1<br />

A 60-year-old man underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy.<br />

A biopsy <strong>of</strong> gastric antrum was submitted <strong>to</strong> pathology<br />

<strong>to</strong> rule out H pylori. The his<strong>to</strong>logic findings are<br />

shown in Figure 1, A through C.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material available<br />

gives <strong>the</strong> following answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? Yes. The gastric<br />

antral mucosa shows expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lamina propria<br />

by chronic inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cells, consisting <strong>of</strong> plasma cells<br />

and small lymphocytes, predominantly located <strong>to</strong>ward <strong>the</strong><br />

luminal aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa, a pattern that is suggestive<br />

<strong>of</strong> H pylori infection.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? Yes. Therefore,<br />

this represents active gastritis. This is a mild form <strong>of</strong> active<br />

gastritis.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? Yes. Hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin (H&E)<br />

examination reveals diagnostic H pylori bacterial forms in<br />

<strong>the</strong> surface mucus layer in close proximity <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> apical<br />

aspect <strong>of</strong> surface epi<strong>the</strong>lial cells.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re glandular atrophy? The biopsy sample available<br />

is not adequate for evaluation <strong>of</strong> atrophic gastritis;<br />

multiple biopsies, including samples <strong>of</strong> gastric body, are<br />

necessary for adequate evaluation <strong>of</strong> glandular atrophy. Is<br />

<strong>the</strong>re intestinal metaplasia? Yes.<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions? The chronic gastritis<br />

in this case involves, at minimum, <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum;<br />

it is advisable <strong>to</strong> obtain biopsy samples <strong>of</strong> both gastric<br />

antrum and body for a better evaluation <strong>of</strong> gastritis, as<br />

recommended by <strong>the</strong> updated Sydney guidelines4 for classification<br />

<strong>of</strong> gastritis.<br />

6. Are additional special features present? No.<br />

7. Are special stains recommended? No.<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Gastric antral mucosa with H pylori–associated<br />

chronic gastritis, mildly active, and focal intestinal<br />

metaplasia.<br />

H PYLORI–ASSOCIATED CHRONIC GASTRITIS<br />

The Helicobacter species consist <strong>of</strong> gram-negative rods<br />

that infect <strong>the</strong> gastric mucosa. Helicobacter pylori bacteria<br />

are 3.5 m long and are generally comma-shaped or have<br />

slightly spiral forms. Helicobacter heilmannii, a rare agent<br />

<strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis, is a 5- <strong>to</strong> 9-m-long bacterium, with<br />

a characteristic tightly corkscrew-shaped, spiral form. 5<br />

Helicobacter pylori infection usually is acquired during<br />

childhood, persisting as chronic gastritis if <strong>the</strong> organism<br />

is not eradicated. During progression <strong>of</strong> gastritis over <strong>the</strong><br />

years, <strong>the</strong> gastric mucosa undergoes a sequence <strong>of</strong> changes<br />

that may lead <strong>to</strong> glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia,<br />

increased risk <strong>of</strong> gastric dysplasia and carcinoma, 6–9 and<br />

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, 10,11 reported<br />

as extranodal, marginal zone, B-cell lymphoma in <strong>the</strong><br />

World Health Organization classification. 12<br />

Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>logic<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> active and chronic gastritis, reflecting <strong>the</strong><br />

presence <strong>of</strong> neutrophils and mononuclear cells (lymphocytes<br />

and plasma cells) in <strong>the</strong> mucosa, respectively. The<br />

term active gastritis is preferred <strong>to</strong> acute gastritis because H<br />

pylori gastritis is a long-standing chronic infection with<br />

ongoing activity. Lymphoid aggregates and lymphoid follicles<br />

may be observed expanding <strong>the</strong> lamina propria, and<br />

rare lymphocytes may enter <strong>the</strong> epi<strong>the</strong>lium. Helicobacter<br />

pylori organisms are found within <strong>the</strong> gastric mucus layer<br />

that overlays <strong>the</strong> apical side <strong>of</strong> gastric surface cells, and<br />

lower numbers are found in <strong>the</strong> lower portions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric<br />

foveolae. Helicobacter pylori may be found within <strong>the</strong><br />

deeper areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa in association with glandular<br />

cells in patients on acid blockers, such as <strong>the</strong> commonly<br />

used pro<strong>to</strong>n pump inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs. 13<br />

Helicobacter pylori–associated gastritis can display different<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> severity. The severity <strong>of</strong> H pylori gastritis activity<br />

may be indicated in a pathology report as mild (rare<br />

neutrophils seen), moderate (obvious neutrophils within<br />

<strong>the</strong> glandular and foveolar epi<strong>the</strong>lium), or severe (numerous<br />

neutrophils with glandular microabscesses and mucosal<br />

erosion or frank ulceration). 4,14<br />

Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic gastritis can manifest<br />

as a pangastritis involving <strong>the</strong> area from <strong>the</strong> pylorus<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric body and cardia, or it may predominantly<br />

involve <strong>the</strong> antrum. Patients with gastric ulcers generally<br />

have antral-predominant gastritis, whereas pangastritis,<br />

Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil 1587

Figure 2. Chronic active gastritis in a patient with Crohn disease. A<br />

glandular abscess is shown; additionally, <strong>the</strong>re are many neutrophils in<br />

<strong>the</strong> lamina propria admixed with a background <strong>of</strong> chronic inflammation<br />

(hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original magnification 20).<br />

or at least multifocal gastritis, is more common in patients<br />

with gastric carcinoma. The latter generally have significant<br />

intestinal metaplasia and gastric oxyntic glandular<br />

atrophy coexisting in <strong>the</strong> background s<strong>to</strong>mach. It is important<br />

<strong>to</strong> make a pathologic diagnosis <strong>of</strong> atrophic gastritis<br />

because gastric atrophy is associated with increased<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> gastric cancer. 15,16 Patients with chronic atrophic<br />

gastritis may have up <strong>to</strong> a 16-fold increased risk <strong>of</strong> developing<br />

gastric carcinoma, compared with <strong>the</strong> general population.<br />

15,17<br />

When large numbers <strong>of</strong> H pylori are present in <strong>the</strong> mucosa,<br />

<strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> typical organisms is generally<br />

possible on H&E stains. However, <strong>the</strong>re are cases <strong>of</strong> chronic,<br />

active gastritis with features suggestive <strong>of</strong> H pylori gastritis<br />

in which <strong>the</strong> organisms are not detected. Several special<br />

stains have been extensively used <strong>to</strong> help identify H<br />

pylori organisms in <strong>the</strong> gastric mucosa, including modified-Giemsa,<br />

Genta, thiazine stains, and immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry<br />

against Helicobacter antigens. The selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

special stain used is largely dependent on preferences related<br />

<strong>to</strong> individual practices. Although, overall, no major<br />

differences in sensitivity and specificity have been reported,<br />

studies have recommended immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stains in a subset <strong>of</strong> cases. 18,19 In our practice, we prefer <strong>to</strong><br />

use immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains for detection <strong>of</strong> H pylori<br />

if organisms are not found on H&E stains in <strong>the</strong> following<br />

cases: (1) if moderate <strong>to</strong> severe chronic gastritis or any<br />

grade <strong>of</strong> active gastritis is present but no Helicobacter organisms<br />

are identified on H&E; (2) when extensive intestinal<br />

metaplasia is present because H pylori density is reduced<br />

in areas <strong>of</strong> intestinal metaplasia; and (3) during<br />

follow-up biopsies after antibiotic treatment for H pylori.<br />

Helicobacter heilmannii may cause similar pathology, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> treatment is similar <strong>to</strong> H pylori. 5<br />

Case 2<br />

A 45-year-old man is seen <strong>to</strong> rule out H pylori. He presents<br />

with a his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> Crohn disease. The his<strong>to</strong>logic findings<br />

are shown in Figure 2.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material results<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pattern <strong>of</strong> answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? Yes. The gastric<br />

antral mucosa shows expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lamina propria<br />

by chronic inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cells, consisting <strong>of</strong> admixed plasma<br />

cells and small lymphocytes, throughout <strong>the</strong> thickness<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? Yes, with an<br />

occasional glandular abscess; <strong>the</strong>refore, <strong>the</strong>re is active gastritis.<br />

Of note, <strong>the</strong> active gastritis has a patchy distribution.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? No. Examination with H&E<br />

stain does not reveal such bacterial forms. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stain is performed.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re atrophy? The biopsy sample available is not<br />

adequate for evaluation <strong>of</strong> atrophic gastritis because <strong>the</strong><br />

biopsy material is only from <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum; multiple<br />

gastric body biopsies are necessary for adequate evaluation<br />

<strong>of</strong> glandular atrophy. There is no intestinal metaplasia.<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions? The chronic gastritis<br />

involves, at minimum, <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum.<br />

6. Are additional special features seen? No. Although<br />

in a case <strong>of</strong> Crohn disease gastritis, epi<strong>the</strong>lioid granulomas<br />

may be present; in this case, no granulomas were<br />

seen.<br />

7. Are special stains recommended? Yes. Helicobacter pylori<br />

immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stain, which is helpful in cases<br />

where Crohn disease is suspected because <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong><br />

H pylori organisms in chronic active gastritis is consistent<br />

with Crohn disease. The H pylori immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stain in this case is negative.<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Gastric antral mucosa with chronic active<br />

gastritis, moderately active, patchy. No H pylori organisms<br />

are identified by H&E or immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry. Note:<br />

These features are consistent with Crohn disease–associated<br />

gastritis.<br />

CROHN DISEASE–ASSOCIATED GASTRITIS<br />

The hallmark his<strong>to</strong>pathologic features <strong>of</strong> Crohn disease–<br />

associated gastritis are <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> patchy, acute inflammation<br />

with possible gastric pit or glandular abscesses,<br />

commonly with a background with lymphoid aggregates.<br />

Recent studies20 reported <strong>the</strong> presentation <strong>of</strong> gastritis<br />

in patients with Crohn disease as a focally enhanced<br />

gastritis, characterized by small collections <strong>of</strong> lymphocytes<br />

and histiocytes surrounding a small group <strong>of</strong> gastric foveolae<br />

or glands, <strong>of</strong>ten with infiltrates <strong>of</strong> neutrophils. In<br />

severe cases, <strong>the</strong>re may be diffuse inflammation in <strong>the</strong><br />

lamina propria, with variable glandular loss, fissures, ulcers,<br />

transmural inflammation, and fibrosis. Noncaseating<br />

epi<strong>the</strong>lioid granulomas may be present in about one third<br />

<strong>of</strong> cases <strong>of</strong> Crohn disease gastritis but are <strong>of</strong>ten not seen,<br />

at least in part, because <strong>of</strong> limited tissue sampling.<br />

When granulomas are identified, <strong>the</strong> differential diagnosis<br />

includes o<strong>the</strong>r forms <strong>of</strong> granuloma<strong>to</strong>us gastritis.<br />

There are infectious and noninfectious causes <strong>of</strong> granuloma<strong>to</strong>us<br />

gastritis. Noninfectious diseases represent <strong>the</strong> usual<br />

cause <strong>of</strong> gastric granulomas and include Crohn disease,<br />

sarcoidosis, and isolated granuloma<strong>to</strong>us gastritis. Sarcoidlike<br />

granulomas may be observed in cocaine users, and<br />

foreign material is occasionally observed in <strong>the</strong> granulomas.<br />

Sarcoidosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach is usually associated with<br />

granulomas in o<strong>the</strong>r organs, especially <strong>the</strong> lungs, hilar<br />

nodes, or salivary glands. A diagnosis <strong>of</strong> idiopathic, iso-<br />

1588 Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil

Figure 3. Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis. A, Chronic<br />

active gastritis involving <strong>the</strong> gastric oxyntic mucosa with glandular atrophy<br />

(hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original magnification 10). Inset shows<br />

rare neutrophils in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> glandular epi<strong>the</strong>lium (white arrows). B, Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stain for H pylori shows a small area with organisms<br />

attached <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface epi<strong>the</strong>lium. Insets show individual Helicobacter<br />

bacteria (thin arrows) with characteristic elongated, slightly<br />

spiral S shape or clusters <strong>of</strong> packed bacteria (thick arrowhead) closely<br />

adherent <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> epi<strong>the</strong>lial cells. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains<br />

are useful in cases such as this one, when H pylori organisms are<br />

closely associated with <strong>the</strong> surface epi<strong>the</strong>lial cells making it difficult <strong>to</strong><br />

ascertain <strong>the</strong> characteristic bacterial morphology on hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin<br />

stains (original magnification 40).<br />

lated, granuloma<strong>to</strong>us gastritis is rendered when known<br />

entities associated with granulomas are excluded.<br />

Case 3<br />

A 60-year-old man presents with a nodularity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

gastric body <strong>to</strong> rule out H pylori. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy<br />

with biopsy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nodular areas was performed.<br />

The his<strong>to</strong>logic findings are shown in Figure 3, A and B.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material results<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pattern <strong>of</strong> answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? Yes.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? Yes. There are<br />

neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa, representing active gastritis.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? No. Examination with H&E<br />

stain does not reveal H pylori bacterial forms. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

is performed.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re atrophy? Yes. There is a reduced number <strong>of</strong><br />

oxyntic glands in <strong>the</strong> biopsy. There is no intestinal metaplasia.<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions? The chronic gastritis<br />

involves, at minimum, <strong>the</strong> gastric body.<br />

6. Are additional special features seen? No.<br />

7. Are special stains recommended? Yes. Helicobacter pylori<br />

immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stain, which is positive.<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Gastric oxyntic mucosa with H pylori–associated<br />

chronic active gastritis and glandular atrophy,<br />

moderate. No intestinal metaplasia is identified. Helicobacter<br />

organisms are identified by immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry.<br />

ATROPHIC GASTRITIS<br />

Several publications, including those reporting <strong>the</strong> Sydney<br />

system and <strong>the</strong> updated Hous<strong>to</strong>n classification <strong>of</strong> gastritis,<br />

have proposed criteria for <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> atrophic<br />

gastritis. Interobserver variability is significant, especially<br />

in <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> antral atrophy. 4,21 Recent advances that<br />

appear <strong>to</strong> decrease <strong>the</strong> interobserver variation in <strong>the</strong> assessment<br />

<strong>of</strong> gastric atrophy have been reported. 14 Atrophy<br />

is more accurately assessed after resolution <strong>of</strong> severe inflammation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa; <strong>the</strong>refore, if <strong>the</strong>re is H pylori<br />

gastritis, <strong>the</strong> infection should be eradicated before atrophy<br />

is difinitively evaluated. When marked inflammation is<br />

present, a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> indefinite for atrophy may be <strong>of</strong>fered,<br />

especially if <strong>the</strong>re is no intestinal metaplasia.<br />

The recommended definition <strong>of</strong> atrophy is <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong><br />

appropriate glands, and atrophy can be scored according<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> severity as mild, moderate, or severe. 22 In<br />

this definition, intestinal metaplasia represents a form <strong>of</strong><br />

atrophy described as metaplastic atrophy (or gastric glandular<br />

atrophy with intestinal metaplasia).<br />

Gastric atrophy is usually associated with intestinal<br />

metaplasia. However, in limited endoscopic biopsies, intestinal<br />

metaplasia might not be sampled, whereas <strong>the</strong><br />

mucosa shows definitive atrophy. Usually gastric atrophy<br />

and intestinal metaplasia occur on a background <strong>of</strong> chronic<br />

gastritis, hence <strong>the</strong> term atrophic gastritis.<br />

Sampling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa for evaluation <strong>of</strong> atrophy and<br />

gastritis is generally adequate by using <strong>the</strong> 5 biopsies recommended<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Sydney system, including 2 biopsies<br />

from <strong>the</strong> antrum, 2 from <strong>the</strong> corpus or body, and 1 from<br />

<strong>the</strong> incisura angularis. 4,21 It is essential for <strong>the</strong> pathologist<br />

<strong>to</strong> have a means <strong>of</strong> determining <strong>the</strong> specific site in <strong>the</strong><br />

s<strong>to</strong>mach where a biopsy is sampled from because specific<br />

<strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> atrophy characterizes <strong>the</strong> different types <strong>of</strong><br />

atrophic gastritis. In atrophic gastritis associated with H<br />

pylori, glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia involve<br />

both <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum and body, whereas in au<strong>to</strong>immune<br />

atrophic gastritis, <strong>the</strong> disease is essentially restricted<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric body. Ideally, <strong>the</strong> precise location is indicated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> endoscopist, and <strong>the</strong> biopsies from different sites<br />

are submitted in separate containers. However, using special<br />

stains can help <strong>the</strong> pathologist determine <strong>the</strong> location<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy fragments received. This approach is exemplified<br />

in case 5.<br />

Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are associated<br />

with increased gastric cancer risk, but unlike <strong>the</strong> intestinal<br />

metaplasia <strong>of</strong> Barrett syndrome, no specific recommendations<br />

for surveillance have been established in <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States, although published data in o<strong>the</strong>r populations<br />

have suggested a benefit. 23 In that study, 23 patients with<br />

Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil 1589

Figure 4. Au<strong>to</strong>immune gastritis. A, The gastric biopsy location in<br />

s<strong>to</strong>mach was not provided in this case (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original<br />

magnification 20). B, Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stain for synap<strong>to</strong>physin<br />

demonstrates enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia (original magnification<br />

20). The inset shows individual enterochromaffin-like cells<br />

staining brown, indicated by <strong>the</strong> arrow. C, Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stain<br />

for gastrin is negative, indicating <strong>the</strong> biopsy site <strong>to</strong> be from <strong>the</strong> gastric<br />

oxyntic mucosa (original magnification 20).<br />

extensive atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia had<br />

an 11% risk <strong>of</strong> gastric malignancy.<br />

Case 4<br />

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy <strong>of</strong> a 60-year-old man<br />

shows gastritis. The pathologist needs <strong>to</strong> rule out H pylori<br />

and gastric atrophy. The gastric site <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy is not<br />

specified. Figure 4, A through C, represents <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>logic<br />

findings.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material results<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pattern <strong>of</strong> answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? Yes.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? Yes. There are<br />

neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa; <strong>the</strong>refore, <strong>the</strong>re is a component<br />

<strong>of</strong> active gastritis.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? No. Examination with H&E<br />

stains do not reveal H pylori bacterial forms. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stain is performed.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re atrophy? If <strong>the</strong> biopsy is from gastric oxyntic<br />

mucosa <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re is atrophy, however, if <strong>the</strong> specimen is<br />

from <strong>the</strong> antrum, it may represent chronic gastritis without<br />

atrophy. There is no intestinal metaplasia.<br />

5. Are special stains recommended? Yes. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stains for synap<strong>to</strong>physin and gastrin are performed.<br />

Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains for synap<strong>to</strong>physin<br />

(Figure 4, B), show a linear pattern <strong>of</strong> synap<strong>to</strong>physin-pos-<br />

itive cells, whereas <strong>the</strong> gastrin stain is negative. Because<br />

gastrin is negative, <strong>the</strong> biopsy is not from <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum<br />

(G cells are characteristically located in <strong>the</strong> antrum<br />

and pylorus), and <strong>the</strong>refore, it can be established that <strong>the</strong><br />

biopsy is <strong>of</strong> oxyntic mucosa with reduced oxyntic glandular<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>iles, establishing a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> atrophy. The linear<br />

arrays <strong>of</strong> synap<strong>to</strong>physin-positive cells represent enterochromaffin-like<br />

cell hyperplasia. Enterochromaffinlike<br />

cell hyperplasia occurs in response <strong>to</strong> hypergastrinemia<br />

that results from hypochlorhydria associated with<br />

gastric oxyntic cell atrophy.<br />

6. Are additional special features seen? No.<br />

7. Is immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stain for H pylori positive?<br />

No.<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Gastric oxyntic mucosa with chronic active<br />

gastritis and glandular atrophy, severe. No intestinal metaplasia<br />

is identified. No Helicobacter organisms are identified.<br />

Note: These features are most suggestive <strong>of</strong> au<strong>to</strong>immune<br />

gastritis.<br />

AUTOIMMUNE ATROPHIC GASTRITIS<br />

This form <strong>of</strong> gastritis (reviewed in Sepulveda et al1 and<br />

Capella et al24 ) is caused by antiparietal cell and anti-intrinsic<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>r antibodies and presents as a chronic gastritis<br />

with oxyntic cell injury, and glandular atrophy essentially<br />

restricted <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> oxyntic mucosa <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric body and<br />

fundus. The his<strong>to</strong>logic changes vary in different phases <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> disease. During <strong>the</strong> early phase, <strong>the</strong>re is multifocal<br />

infiltration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lamina propria by mononuclear cells and<br />

eosinophils and focal T-cell lymphocyte infiltration <strong>of</strong> oxyntic<br />

glands with glandular destruction. Focal mucous<br />

neck cell hyperplasia (pseudopyloric metaplasia), and hypertrophic<br />

changes <strong>of</strong> parietal cells are also observed.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> florid phase, <strong>the</strong>re is increased lymphocytic<br />

inflammation, oxyntic gland atrophy, and focal intestinal<br />

metaplasia. The end stage is characterized by diffuse involvement<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric body and fundus by chronic atrophic<br />

gastritis associated with multifocal intestinal metaplasia.<br />

In contrast <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric body, <strong>the</strong> antrum is<br />

spared. Recently, a distinct form <strong>of</strong> au<strong>to</strong>immune gastritis,<br />

characterized by atrophic pangastritis, was reported in a<br />

small group <strong>of</strong> patients with systemic au<strong>to</strong>immune disorders.<br />

25<br />

Au<strong>to</strong>immune gastritis is a relatively rare disease but<br />

represents <strong>the</strong> most frequent cause <strong>of</strong> pernicious anemia<br />

in temperate climates. The risk <strong>of</strong> gastric adenocarcinoma<br />

was reported <strong>to</strong> be at least 2.9 times higher in patients<br />

with pernicious anemia than in <strong>the</strong> general population,<br />

and <strong>the</strong>re is also an increased risk <strong>of</strong> gastric carcinoid tumors.<br />

Case 5<br />

A 47-year-old woman presents with a his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> celiac<br />

disease. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed,<br />

with biopsy <strong>of</strong> gastric antrum. The pathologist needs <strong>to</strong><br />

rule out H pylori. Figure 5, A and B, illustrates <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>logic<br />

findings.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material results<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pattern <strong>of</strong> answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? Yes. There are<br />

large numbers <strong>of</strong> intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial lymphocytes.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? No.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? No. Examination with H&E<br />

1590 Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil

Figure 5. Lymphocytic gastritis. A, Gastric mucosal surface epi<strong>the</strong>lium<br />

is studded with intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial small lymphocytes (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin,<br />

original magnification 20). B, Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry highlights numerous<br />

CD3-positive T lymphocytes staining dark brown (original magnification<br />

20). The lymphocytes predominantly infiltrate <strong>the</strong> surface<br />

and foveolar epi<strong>the</strong>lium. The thick arrow points <strong>to</strong> light-brown background<br />

stain found in some glandular cells. The inset shows a higher<br />

magnification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface epi<strong>the</strong>lium containing many intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial<br />

lymphocytes (original magnification 40). One individual lymphocyte<br />

is indicated by <strong>the</strong> arrow. T lymphocytes stain dark brown, whereas<br />

<strong>the</strong> nucleus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> epi<strong>the</strong>lial cell nuclei stain with <strong>the</strong> blue counterstain.<br />

stain does not reveal H pylori bacterial forms. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

is performed.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re atrophy? No. There is no glandular atrophy<br />

and no intestinal metaplasia.<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions? The chronic gastritis<br />

involves, at minimum, <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum.<br />

6. Are additional special features seen? Yes. The specific<br />

features in this biopsy include a characteristic intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial<br />

lymphocy<strong>to</strong>sis. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stain for CD3 is<br />

positive, highlighting a population <strong>of</strong> T lymphocytes in<br />

<strong>the</strong> mucosa and, typically, many intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial lymphocytes.<br />

7. Are special stains recommended? Yes. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stain for H pylori, which is negative.<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Chronic gastritis with increased intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial<br />

T lymphocytes. No Helicobacter organisms are identified.<br />

Note: These features are consistent with lymphocytic<br />

gastritis–associated with celiac disease.<br />

LYMPHOCYTIC GASTRITIS<br />

Lymphocytic gastritis is a type <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis characterized<br />

by marked infiltration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gastric surface and<br />

foveolar epi<strong>the</strong>lium by T lymphocytes and by chronic inflammation<br />

in <strong>the</strong> lamina propria. A diagnosis can be rendered<br />

when 30 or more lymphocytes per 100 consecutive<br />

epi<strong>the</strong>lial cells are observed, and <strong>the</strong> counts are recommended<br />

in biopsies from <strong>the</strong> gastric corpus. The endoscopic<br />

pattern is, in some cases, described as varioliform<br />

gastritis. The cause <strong>of</strong> lymphocytic gastritis is usually unknown,<br />

but some cases are seen in patients with glutensensitive<br />

enteropathy/celiac disease and in Ménétrier disease.<br />

Smaller numbers <strong>of</strong> intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial lymphocytes can also<br />

be seen in H pylori gastritis, but <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> lymphocytic<br />

gastritis should be reserved for cases with marked<br />

intraepi<strong>the</strong>lial lymphocy<strong>to</strong>sis in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> active H<br />

pylori gastritis. Lymphocytic gastritis can be observed in<br />

children but is usually detected in late adulthood, with<br />

average age <strong>of</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> 50 years.<br />

Case 6<br />

A 75-year-old woman presents after esophagogastroduodenoscopy.<br />

Gastric antrum shows gastritis; <strong>the</strong> pathologist<br />

is asked <strong>to</strong> rule out H pylori. The his<strong>to</strong>logic findings<br />

are shown in Figure 6.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material results<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pattern <strong>of</strong> answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? There is minimal<br />

chronic gastritis.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? No.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? No. Examination <strong>of</strong> H&E stains<br />

does not reveal H pylori bacterial forms.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re atrophy? No. There is no atrophy or intestinal<br />

metaplasia.<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions? The chronic gastritis<br />

involves, at minimum, <strong>the</strong> gastric antrum.<br />

6. Are additional special features seen? Yes. There are<br />

diagnostic special features, including foveolar hyperplasia<br />

with a corkscrew appearance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> foveolae. The foveolar<br />

epi<strong>the</strong>lium shows reactive cy<strong>to</strong>logic features, including reduced<br />

cy<strong>to</strong>plasmic mucin. The lamina propria shows congestion<br />

and smooth muscle hyperplasia, with prominent<br />

muscularization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most superficial mucosa.<br />

7. Are special stains recommended? No ancillary tests<br />

are performed.<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Gastric antral mucosa with features consistent<br />

with reactive gastropathy. No H pylori organisms<br />

are identified.<br />

CHRONIC, REACTIVE (CHEMICAL) GASTROPATHY<br />

Chronic reactive gastropathy (also know as chemical<br />

gastropathy) is very common in current clinical practice.<br />

The mucosal changes are usually more prominent in <strong>the</strong><br />

prepyloric region, but <strong>the</strong>y may extend <strong>to</strong> involve <strong>the</strong> oxyntic<br />

mucosa. The usual underlying causes include chronic<br />

bile reflux and long-term NSAID intake. The his<strong>to</strong>pathologic<br />

features include mucosal edema, congestion, fibromuscular<br />

hyperplasia in <strong>the</strong> lamina propria, and foveolar<br />

hyperplasia with a corkscrew appearance in <strong>the</strong> most severe<br />

forms. The foveolar epi<strong>the</strong>lium characteristically<br />

shows reactive nuclear features and reduction <strong>of</strong> mucin.<br />

The epi<strong>the</strong>lial changes occur with little background chronic<br />

inflammation. However, if <strong>the</strong>re is erosion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mucosa,<br />

superficial neutrophils may be present. Erosive gas-<br />

Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil 1591

Figure 6. Reactive gastropathy (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original magnification<br />

20).<br />

Figure 7. Erosive gastritis and cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus-associated gastritis. A,<br />

Gastric mucosa with erosion in a patient with his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> nonsteroidal<br />

anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry drug use (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original magnification<br />

20). B, Gastric mucosal erosion with granulation tissue. Inset shows<br />

tritis (Figure 7, A) can present clinically as acute gastritis,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten associated with NSAID intake.<br />

The features associated with bile reflux are typically<br />

found in patients with partial gastrec<strong>to</strong>my, in whom, <strong>the</strong><br />

lesions develop near <strong>the</strong> surgical s<strong>to</strong>ma. However, alterations<br />

induced by bile reflux also affect <strong>the</strong> intact s<strong>to</strong>mach.<br />

A recent study 26 reported altered mucin expression in reactive<br />

gastropathy, including aberrant expression <strong>of</strong><br />

MUC5Ac in pyloric glands. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> mucin-expression<br />

patterns can be useful <strong>to</strong> support a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> reactive<br />

gastropathy; however, additional studies are warranted<br />

<strong>to</strong> validate this potential application <strong>of</strong> mucin immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry.<br />

Case 7<br />

A 45-year-old woman presents with a his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> bone<br />

marrow transplant. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy shows<br />

gastric erosion. The his<strong>to</strong>logic findings are represented in<br />

Figure 7, B.<br />

Findings. Examination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy material results<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pattern <strong>of</strong> answers:<br />

1. Are <strong>the</strong>re features <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis? Yes. The sample<br />

<strong>of</strong> gastric mucosa reveals mucosal erosion with granulation<br />

tissue and associated chronic and acute inflammation.<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong>re neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa? Yes. There are<br />

superficial neutrophils in <strong>the</strong> mucosa, but <strong>the</strong>y are limited<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> mucosal erosion.<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong>re Helicobacter? No. Examination with H&E<br />

stain does not reveal such bacterial forms.<br />

4. Is <strong>the</strong>re atrophy? No. There is no atrophy or intestinal<br />

metaplasia.<br />

5. What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>pography <strong>of</strong> lesions? Away from <strong>the</strong><br />

areas <strong>of</strong> erosion, <strong>the</strong>re is no evidence <strong>of</strong> gastritis; <strong>the</strong>refore,<br />

<strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy is not contribu<strong>to</strong>ry in this case.<br />

6. Are additional special features seen? Yes. There are<br />

special features including enlarged cells, arousing suspicion<br />

<strong>of</strong> cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus inclusions in <strong>the</strong> granulation tissue.<br />

7. Are special stains recommended? Yes. Immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical<br />

stain for cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus reveals rare but characteristic<br />

viral inclusions (not shown).<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong>. Gastric antral mucosa with erosion and cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus<br />

inclusions, consistent with cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirusassociated<br />

gastritis.<br />

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS GASTRITIS<br />

Cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus infection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach is observed<br />

in patients with underlying immunosuppression. His<strong>to</strong>logically,<br />

intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions and smaller<br />

intracy<strong>to</strong>plasmic inclusions in enlarged cells are characteristic.<br />

A patchy, mild inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry infiltrate is observed<br />

in <strong>the</strong> lamina propria. Viral inclusions are present in endo<strong>the</strong>lial<br />

or mesenchymal cells in <strong>the</strong> lamina propria and<br />

may be seen in gastric epi<strong>the</strong>lial cells. Severe activity may<br />

result in mucosal ulceration.<br />

←<br />

cy<strong>to</strong>megalovirus inclusion. This single inclusion is identified by <strong>the</strong> arrow<br />

on <strong>the</strong> background granulation tissue (hema<strong>to</strong>xylin-eosin, original<br />

magnifications 20 and 40 [inset]).<br />

1592 Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil

COMMENT<br />

Most types <strong>of</strong> gastritis can be diagnosed with H&E<br />

stains. To reach a determination <strong>of</strong> etiology and a specific<br />

diagnostic entity, a limited list <strong>of</strong> questions can be used<br />

<strong>to</strong> evaluate <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>pathology <strong>of</strong> gastric biopsies, which<br />

can lead <strong>to</strong> a pattern <strong>of</strong> answers that corresponds <strong>to</strong> a<br />

specific diagnosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most common types <strong>of</strong> gastritis.<br />

Although not ideal, <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> gastritis can be<br />

reached from limited biopsy material, even when <strong>the</strong> location<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biopsy is not indicated. If <strong>the</strong> biopsy site is<br />

not known, immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains for synap<strong>to</strong>physin<br />

and gastrin can help determine <strong>the</strong> biopsy location,<br />

permitting a specific diagnosis <strong>of</strong> atrophic gastritis type.<br />

Helicobacter pylori immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical stains can be particularly<br />

useful when moderate <strong>to</strong> severe chronic gastritis<br />

or any active gastritis is present but no Helicobacter organisms<br />

are identified on H&E stains, when extensive intestinal<br />

metaplasia is present, and <strong>to</strong> evaluate follow-up biopsies<br />

after antibiotic treatment for H pylori.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day, <strong>the</strong>re are a number <strong>of</strong> cases with<br />

a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> chronic inactive gastritis, generally mild, for<br />

which a specific etiology cannot be determined by his<strong>to</strong>pathologic<br />

examination alone. This may be accounted for<br />

by limited tissue sampling, nonspecific focal, mild, chronic<br />

inactive gastritis associated with various systemic disorders,<br />

or as yet uncharacterized forms <strong>of</strong> gastritis.<br />

References<br />

1. Sepulveda AR, Dore MP, Bazzoli F. Chronic gastritis. Available at: http://<br />

www.emedicine.com. Accessed November 27, 2007.<br />

2. Srivastava A, Lauwers GY. Pathology <strong>of</strong> non-infective gastritis. His<strong>to</strong>pathology.<br />

2007;50:15–29.<br />

3. McKenna BJ, Appelman HD. Primer: his<strong>to</strong>pathology for <strong>the</strong> clinician—how<br />

<strong>to</strong> interpret biopsy information for gastritis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepa<strong>to</strong>l.<br />

2006;3:165–171.<br />

4. Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P, <strong>the</strong> participants in <strong>the</strong> International<br />

Workshop on <strong>the</strong> His<strong>to</strong>pathology <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>, Hous<strong>to</strong>n 1994. Classification<br />

and grading <strong>of</strong> gastritis: <strong>the</strong> updated Sydney System. Am J Surg Pathol.<br />

1996;20:1161–1181.<br />

5. Singhal AV, Sepulveda AR. Helicobacter heilmannii gastritis: a case study<br />

with review <strong>of</strong> literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1537–1539.<br />

6. Sipponen P, Kekki M, Haapakoski J, Ihamaki T, Siurala M. Gastric cancer<br />

risk in chronic atrophic gastritis: statistical calculations <strong>of</strong> cross-sectional data. Int<br />

J Cancer. 1985;35:173–177.<br />

7. Uemura N, Okamo<strong>to</strong> S, Yamamo<strong>to</strong> S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection<br />

and <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789.<br />

8. Asaka M, Sugiyama T, Nobuta A. et al. Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia<br />

in Japan: results <strong>of</strong> a large multicenter study: Helicobacter. 2001;6:294–<br />

299.<br />

9. Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum S, Archer M. A model for<br />

gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet. 1975;2:58–60.<br />

10. Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection<br />

and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267–1271.<br />

11. Wo<strong>the</strong>rspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter<br />

pylori–associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;<br />

338:1175–1176.<br />

12. Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Pathology and Genetics <strong>of</strong> Tumours<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hema<strong>to</strong>poietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001.<br />

World Health Organization Classification <strong>of</strong> Tumours; vol 3.<br />

13. Tagkalidis P, Royce S, Macrae F, Bhathal P. Selective colonization by Helicobacter<br />

pylori <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deep gastric glands and intracellular canaliculi <strong>of</strong> parietal<br />

cells in <strong>the</strong> setting <strong>of</strong> chronic pro<strong>to</strong>n pump inhibi<strong>to</strong>r use. Eur J Gastroenterol<br />

Hepa<strong>to</strong>l. 2002;14:453–456.<br />

14. Rugge M, Genta RM. Staging and grading <strong>of</strong> chronic gastritis. Hum Pathol.<br />

2005;36:228–233.<br />

15. Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> relationship<br />

between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology.<br />

1998;114:1169–1179.<br />

16. Correa P, Hough<strong>to</strong>n J. Carcinogenesis <strong>of</strong> Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology.<br />

2007;133:659–72.<br />

17. Sepulveda AR, Coelho LG. Helicobacter pylori and gastric malignancies.<br />

Helicobacter. 2002;7(suppl 1):37–42.<br />

18. Jonkers D, S<strong>to</strong>bberingh E, de Bruine A, Arends JW, S<strong>to</strong>ckbrugger R. Evaluation<br />

<strong>of</strong> immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry for <strong>the</strong> detection <strong>of</strong> Helicobacter pylori in gastric<br />

mucosal biopsies. J Infect. 1997;35:149–154.<br />

19. Toulaymat M, Marconi S, Garb J, Otis C, Nash S. Endoscopic biopsy pathology<br />

<strong>of</strong> Helicobacter pylori gastritis: comparison <strong>of</strong> bacterial detection by immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry<br />

and Genta stain. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:778–781.<br />

20. Xin W, Greenson JK. The clinical significance <strong>of</strong> focally enhanced gastritis.<br />

Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1347–1351.<br />

21. Price A. The Sydney System: his<strong>to</strong>logical division. J Gastroenterol Hepa<strong>to</strong>l.<br />

1991;6:209–222.<br />

22. Rugge M, Correa P, Dixon MF. et al. Gastric mucosal atrophy: interobserver<br />

consistency using new criteria for classification and grading. Aliment Pharmacol<br />

Ther. 2002;16:1249–1259.<br />

23. Whiting JL, Sigurdsson A, Rowlands DC, Hallissey MT, Fielding JW. The<br />

long term results <strong>of</strong> endoscopic surveillance <strong>of</strong> premalignant gastric lesions. Gut.<br />

2002;50:378–381.<br />

24. Capella R, Fiocca C, Cornaggia M. Au<strong>to</strong>immune gastritis. In: Graham DY,<br />

Genta RM, Dixon MF, eds. <strong>Gastritis</strong>. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams; 1999:<br />

79–96.<br />

25. Jevremovic D, Torbenson M, Murray JA, Burgart LJ, Abraham SC. Atrophic<br />

au<strong>to</strong>immune pangastritis: a distinctive form <strong>of</strong> antral and fundic gastritis associated<br />

with systemic au<strong>to</strong>immune disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1412–1419.<br />

26. Mino-Kenudson M, Tomita S, Lauwers GY. Mucin expression in reactive<br />

gastropathy: an immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:<br />

86–90.<br />

Archives <strong>of</strong> Pathology & Labora<strong>to</strong>ry Medicine and Archives <strong>of</strong> Ophthalmology will publish a joint<br />

<strong>the</strong>me issue on ophthalmic pathology in August 2009. Articles on diagnostic procedures, pathologic<br />

mechanistic pathways, and translational research in retinoblas<strong>to</strong>ma, melanoma, lymphoma,<br />

orbital, and adnexal tumors in ophthalmic pathology will have <strong>the</strong> best chance for consideration<br />

in this <strong>the</strong>me issue. Manuscripts must be submitted no later than February 1, 2009 for<br />

consideration in <strong>the</strong> joint <strong>the</strong>me issue. All submissions will undergo our usual peer review process.<br />

Important: When submitting a manuscript for this <strong>the</strong>me issue, be certain <strong>to</strong> mention this in<br />

both <strong>the</strong> cover letter and <strong>the</strong> Comment section within <strong>the</strong> AllenTrack submission system.<br />

To view our Instructions for Authors, visit<br />

http://arpa.allenpress.com/pdf/instructionsforauthors.pdf<br />

Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 132, Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 <strong>Pathologic</strong> <strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gastritis</strong>—Sepulveda & Patil 1593