arizona military museum courier - Department of Emergency ...

arizona military museum courier - Department of Emergency ...

arizona military museum courier - Department of Emergency ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

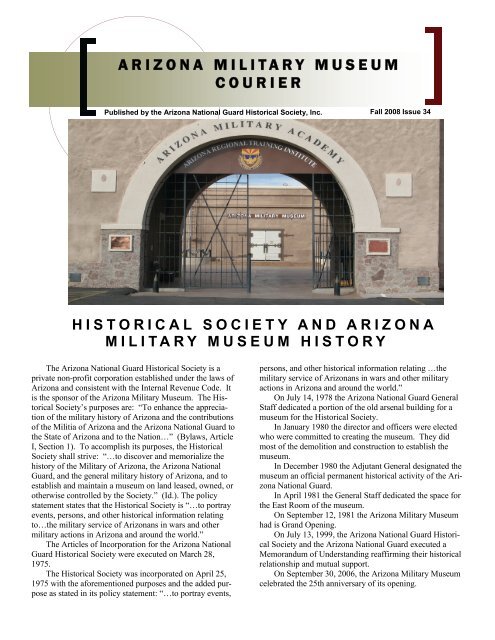

ARIZONA MILITARY MUSEUM<br />

COURIER<br />

Published by the Arizona National Guard Historical Society, Inc.<br />

The Arizona National Guard Historical Society is a<br />

private non-pr<strong>of</strong>it corporation established under the laws <strong>of</strong><br />

Arizona and consistent with the Internal Revenue Code. It<br />

is the sponsor <strong>of</strong> the Arizona Military Museum. The Historical<br />

Society’s purposes are: “To enhance the appreciation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>military</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Arizona and the contributions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Militia <strong>of</strong> Arizona and the Arizona National Guard to<br />

the State <strong>of</strong> Arizona and to the Nation…” (Bylaws, Article<br />

I, Section 1). To accomplish its purposes, the Historical<br />

Society shall strive: “…to discover and memorialize the<br />

history <strong>of</strong> the Military <strong>of</strong> Arizona, the Arizona National<br />

Guard, and the general <strong>military</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Arizona, and to<br />

establish and maintain a <strong>museum</strong> on land leased, owned, or<br />

otherwise controlled by the Society.” (Id.). The policy<br />

statement states that the Historical Society is “…to portray<br />

events, persons, and other historical information relating<br />

to…the <strong>military</strong> service <strong>of</strong> Arizonans in wars and other<br />

<strong>military</strong> actions in Arizona and around the world.”<br />

The Articles <strong>of</strong> Incorporation for the Arizona National<br />

Guard Historical Society were executed on March 28,<br />

1975.<br />

The Historical Society was incorporated on April 25,<br />

1975 with the aforementioned purposes and the added purpose<br />

as stated in its policy statement: “…to portray events,<br />

Fall 2008 Issue 34<br />

HISTORICAL SOCIETY AND ARIZONA<br />

MILITARY MUSEUM HISTORY<br />

persons, and other historical information relating …the<br />

<strong>military</strong> service <strong>of</strong> Arizonans in wars and other <strong>military</strong><br />

actions in Arizona and around the world.”<br />

On July 14, 1978 the Arizona National Guard General<br />

Staff dedicated a portion <strong>of</strong> the old arsenal building for a<br />

<strong>museum</strong> for the Historical Society.<br />

In January 1980 the director and <strong>of</strong>ficers were elected<br />

who were committed to creating the <strong>museum</strong>. They did<br />

most <strong>of</strong> the demolition and construction to establish the<br />

<strong>museum</strong>.<br />

In December 1980 the Adjutant General designated the<br />

<strong>museum</strong> an <strong>of</strong>ficial permanent historical activity <strong>of</strong> the Arizona<br />

National Guard.<br />

In April 1981 the General Staff dedicated the space for<br />

the East Room <strong>of</strong> the <strong>museum</strong>.<br />

On September 12, 1981 the Arizona Military Museum<br />

had is Grand Opening.<br />

On July 13, 1999, the Arizona National Guard Historical<br />

Society and the Arizona National Guard executed a<br />

Memorandum <strong>of</strong> Understanding reaffirming their historical<br />

relationship and mutual support.<br />

On September 30, 2006, the Arizona Military Museum<br />

celebrated the 25th anniversary <strong>of</strong> its opening.

Courier page 2<br />

Published by the Arizona<br />

National Guard Historical<br />

Society, 5636 E<br />

McDowell Rd, Bldg<br />

M5320, Phoenix, AZ<br />

85008-3495<br />

President/Director:<br />

Joseph Abodeely<br />

Vice President:<br />

Thomas Quarelli<br />

Secretary:<br />

Carolyn Feller<br />

Treasurer:<br />

Klaus Foerst<br />

Board <strong>of</strong> Director<br />

Members:<br />

Jean McColgin<br />

Anna Kroger<br />

Dan Mardian<br />

Harry/Mary Hensell<br />

Rick White<br />

Eugene Cox<br />

George Notarpole<br />

Jon Falk<br />

Robert Lutes<br />

Trudie Cooke<br />

Ex-Officio Board Member:<br />

MG David Rataczak<br />

Museum Hours:<br />

The Arizona Military<br />

Museum is temporarily<br />

closed pending ro<strong>of</strong><br />

repairs.<br />

How to Contact Us:<br />

Write or call<br />

Phone: 602.267.2676<br />

Or: 602-253-2378<br />

Fax: 602.267.2632<br />

DSN: 853-2676<br />

Editors: Joseph<br />

Abodeely and Trudie<br />

Cooke<br />

Submit address<br />

changes and articles to<br />

the Arizona Military<br />

Museum, 5636 E<br />

McDowell Rd, Phoenix,<br />

AZ 85008-3495.<br />

Arizona National Guard<br />

Historical Society<br />

“Lest We Forget”<br />

REPORT TO THE MEMBERSHIP<br />

I have good news and bad news. The bad news is that<br />

the <strong>museum</strong> is still closed to the public. The Facilities<br />

Management Office (FMO) determined that the <strong>museum</strong> should be closed right after he<br />

saw the two cracked trusses in November 2007, and the engineers hired by the FMO<br />

said to close the <strong>museum</strong>. Risk management has concurred based on the information<br />

presented by their report. I complained to no avail about only the <strong>museum</strong> being singled<br />

out to be closed down while the RTI classrooms (immediately to the west) and the<br />

dining facility (immediately to the right) remained open because all three areas are under<br />

the same ro<strong>of</strong> in the north building <strong>of</strong> the RTI. The FMO engineers and an independent<br />

engineer we hired said the shoring up <strong>of</strong> the trusses was sufficient to hold them<br />

in place; but the engineers have taken the position to keep the <strong>museum</strong> closed supposedly<br />

for safety reasons. The RTI classroom area, on the west side <strong>of</strong> the <strong>museum</strong>, is<br />

still open to the public. And, the supposedly emergency situation is still not resolved.<br />

The engineers report to the FMO took about six months to recommend repairing the<br />

entire ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> the north building for a cost <strong>of</strong> $1.9 million. The Guard applied for<br />

funds from National Guard Bureau to fix the building. We made the recommendation<br />

that it take a more conservative approach and make only necessary repairs. On September<br />

3, the Guard informed the Board that there was no money allocated for the repairs<br />

at this time, and the Guard would not allow the <strong>museum</strong> to reopen to the public<br />

relying on the engineers’ recommendation to Risk Management.<br />

On September 10, I was given 45 minutes notice to attend a meeting with the engineers,<br />

the FMO, the Chief <strong>of</strong> Staff, and the Army Assistant AG. Dan Mardian and I<br />

were informed that the Guard just got money from NGB to do the major project—the<br />

$1,900,000. The discussion dealt with whether it was a viable option to repair only the<br />

broken trusses in the <strong>museum</strong> and the dining facility or fix all the trusses and the ro<strong>of</strong>.<br />

It appears the Guard will do all the repairs now to avoid potential problems in the future.<br />

The <strong>museum</strong> may have to remove all <strong>of</strong> its artifacts during the construction. In<br />

other words dismantle the <strong>museum</strong>. The FMO and the Chief <strong>of</strong> Staff assured me they<br />

will work closely with us during construction and the likely removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>museum</strong> items.<br />

Dan Mardian expressed our belief that the trusses were cracked due to A/C units on the<br />

ro<strong>of</strong>, but the engineers were adamant that the other trusses were at risk due to wear.<br />

The engineers favored the total-repair option. We have been closed to the public for<br />

the past ten months, and nobody on the Board believes an emergency exists only in<br />

the <strong>museum</strong> to require its closure. But that is a moot point now. I asked the FMO<br />

about the time frame, and he said that demolition would commence soon and that the<br />

<strong>museum</strong> should be completed by around May 2009. I am taking the position <strong>of</strong> let’s<br />

take lemons and make lemonade. We will have a new building for the <strong>museum</strong> when<br />

all is done. But we’ve got to open soon. A <strong>museum</strong> not open to the public is merely<br />

a collection.<br />

The good news is that we are still working to keep one <strong>of</strong> the finest <strong>military</strong> <strong>museum</strong>s<br />

in the country alive. On February 14, 2008 (Valentine’s Day and Arizona Statehood<br />

Day), the Arizona Military Museum participated in the annual Museums on the

Letter to Membership continued.<br />

Courier page 3<br />

the Mall event held on the grounds <strong>of</strong> the State Capitol. We had two tables with artifacts on display. Harry<br />

and Mary Hensell and I attended. Rick White and Jon Falk helped transport our artifacts to and from the<br />

event. Numerous other <strong>museum</strong>s also participated, and the event always gives your <strong>museum</strong> great visibility.<br />

The <strong>museum</strong> received a $1700.00 grant from the Arizona Historical Society which we used to purchase a<br />

firepro<strong>of</strong> lateral file cabinet. We preserve important documents in it such as the original muster rolls <strong>of</strong> the 1 st<br />

Arizona Volunteer Infantry. We really appreciate the continued support from AHS. We did not ask for a grant<br />

this year since the <strong>museum</strong> was still closed. On March 2 and 3, I attended the Arizona Library, Archives, and<br />

Public Records Convocation in Tucson. It was informative about records collections, preservation, and conservation.<br />

In April, three Board members (George Notarpole, Trudie Cooke, and me) attended the Museums<br />

Association <strong>of</strong> Arizona (MAA) annual convention in Wickenburg. I spoke about the creation, maintenance,<br />

and operation <strong>of</strong> the Arizona Military Museum. The convention was very informative about <strong>museum</strong> governance<br />

and procedures.<br />

Also, in April your Board <strong>of</strong> Directors was selected for the year. The Officers and Board <strong>of</strong> Directors are<br />

Col. Joseph Abodeely (USA Ret.)-President; BG Thomas Quarelli (ANG Ret.)-Vice President; LTC Carolyn<br />

Feller (USAR Ret.)-Secretary; Klaus Foerst-Treasurer; and the Directors are Jean McColgin, Anna Kroger,<br />

Dan Mardian, CSM Harry Hensell (Ret.), Mary Hensell, Rick White, Eugene Cox, George Notarpole, Jon<br />

Falk, Robert Lutes, and Trudie Cooke.<br />

MG David Rataczak serves as an ex-<strong>of</strong>ficio member <strong>of</strong> the Board <strong>of</strong> Directors. He will be retiring this<br />

year, and we wish to thank him for the support he has given us in the past.<br />

While the <strong>museum</strong> has been closed, Board members installed slat walls in the display cases to facilitate<br />

hanging artifacts from the walls. We have conducted inventories <strong>of</strong> USPFO weapons and vehicles, and also <strong>of</strong><br />

our own weapons and artifacts. Trudie Cooke and Nancy Goodson have been working on the library; and<br />

George, Nancy, Trudie, and I have been working on specific inventories <strong>of</strong> the items displayed in each display<br />

case.<br />

I attended a MAA workshop on August 18 in Tucson at AHS about the changing population growth in Arizona<br />

and how it will affect <strong>museum</strong>s. Arizona will double its population by 2030 with many more retirees and<br />

Hispanics. There will be a rise <strong>of</strong> the “creative class” which will be 30% <strong>of</strong> the population with 50% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

population’s income.<br />

On Saturday, November 8, we will celebrate Veterans’ Day. We will have artifacts from the <strong>museum</strong> on<br />

display in the quadrangle and <strong>military</strong> motor vehicles, provided by the two <strong>military</strong> motor vehicle clubs in the<br />

Valley. We will also have a book sale. Come and visit with us. We need the morale booster. Of course, admission<br />

is free.<br />

We are looking forward to the Arizona’s centennial celebration in 2012, and we are hoping to be a focal<br />

point <strong>of</strong> interest because <strong>of</strong> our portrayal <strong>of</strong> Arizona’s <strong>military</strong> history. We are applying for the Arizona Centennial<br />

Commission’s Legacy Project certification. We are pleased and proud to honor Arizona’s veterans,<br />

militia and National Guard members who have served in the past and present. We are extremely pleased to<br />

have guest articles in this Courier from Marshall Trimble, the Official State Historian, Jim Turner, the Historian<br />

from the Arizona Historical Society, and John Langellier, Director, Sharlot Hall Museum.<br />

The Officers and Directors <strong>of</strong> the Historical Society have kept the <strong>museum</strong> going, and we would like to<br />

continue to do so. We do it voluntarily to provide the Arizona National Guard and the public one <strong>of</strong> the best<br />

<strong>military</strong> <strong>museum</strong>s in the United States. We could not do what we do without your support and the support <strong>of</strong><br />

MG Rataczak and his staff. As the state’s centennial is approaching, the <strong>museum</strong> is gearing up to be the showcase<br />

for the Arizona National Guard. We hope you’ll help.<br />

Joseph E. Abodeely<br />

Colonel (USA Ret)<br />

President, AZNG Historical Society

Courier page 4<br />

Geronimo’s Last Campaign<br />

By Marshall Trimble, Official Arizona State Historian<br />

There were stretches <strong>of</strong> country picturesque<br />

to look upon and capable <strong>of</strong> cultivation, especially<br />

with irrigation; and other expanses not<br />

a bit more fertile than so manmade brickyards,<br />

where all was desolation, the home <strong>of</strong><br />

the cactus and the coyote. Arizona was in<br />

those days separated from “God’s country”<br />

by a space <strong>of</strong> more than fifteen hundred<br />

miles, without a railroad, and the <strong>of</strong>ficer or<br />

soldier who once got out there rarely returned<br />

for years. (p. 3)<br />

….During this campaign we were <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

obliged to leave the warm valleys in the<br />

morning and climb to the higher altitudes and<br />

go into bivouac upon summits where the<br />

snow was hip deep, as on the Matitzal (sic.),<br />

the Mogollon plateau, and the Sierra Ancha.<br />

To add to the discomfort, the pine was so<br />

thoroughly soaked through with snow and<br />

rain it would not burn, and unless cedar could<br />

be found, the command was in bad luck. (p.<br />

185)<br />

Captain John G. Bourke, On the Border<br />

with Crook, 1971<br />

In the years following the Civil War, the Frontier Army was<br />

charged with the thankless task <strong>of</strong> keeping the peace in the<br />

West. That meant not only protecting the whites from the Indians<br />

but protecting the Indians from the Whites. Playing peacemaker,<br />

the Army was caught between a rock and a hard place.<br />

There were some 2,600 soldiers to police about 200,000 Indians.<br />

Many times the natives were better armed than the soldiers.<br />

The Army was also caught in the middle between eastern<br />

politicians and activists who believed the Army was too harsh<br />

in its treatment <strong>of</strong> Indians and the westerners who insisted the<br />

Army mollycoddled the natives.<br />

Deaths resulting from such diseases as cholera and yellow<br />

fever killed far more than those resulting from fighting Indians.<br />

Between the years 1860 and 1886, 1,993 soldiers were killed or<br />

wounded in the Indian Wars. In 1886, 1,217 soldiers died from<br />

cholera alone.<br />

Harsh living conditions, fatigue, poor pay, poor rations, and<br />

little appreciation from his fellow countrymen were the grim<br />

prospects the soldiers faced. They were <strong>of</strong>ten sent into battle<br />

with obsolete weapons and equipment as well as under strength<br />

in numbers. Desertion, alcoholism and suicide rates were high<br />

on the isolated <strong>military</strong> posts. Loneliness and boredom was the<br />

soldier’s constant companion. Typical meals on the posts consisted<br />

<strong>of</strong> such culinary delights as beef hash, dry bread, and<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee for breakfast. Evening meals were just simply bread and<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee.<br />

Punishment was harsh especially for acts such as drunkenness<br />

and desertion. Yet these men became good soldiers. Under<br />

the pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism <strong>of</strong> the corps <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficers and noncommissioned<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers, along with the rigid discipline instilled,<br />

Geronimo, circa 1886.<br />

the small Spartan army made up largely <strong>of</strong> Irish and German<br />

immigrants became veteran, reliable and even efficient. It was<br />

admired and understood by foreign <strong>military</strong> observers who ventured<br />

west to observe them.<br />

Following General George Crook’s successful 1872-1873<br />

campaign against the Apache in the rugged mountains <strong>of</strong> central<br />

Arizona, the tribes were located on reservations after agreeing<br />

to the federal government’s promise to provide provisions.<br />

Trouble began almost immediately after the Chiricahua were<br />

relocated to San Carlos in 1876, and thrown in with other<br />

Apache groups who regarded them as enemies. Also, leaders<br />

like Juh, Chatto, Chihuahua, and Victorio were unhappy with<br />

reservation life and continued bolting the reservation, leading<br />

raids in Arizona and Mexico. This initiated the so-called<br />

“renegade” period in the Apache Wars where soldiers would go<br />

in pursuit <strong>of</strong> those who left the reservation.<br />

Two issues led to the final outbreak. The Apache men had a<br />

custom <strong>of</strong> biting <strong>of</strong>f the nose <strong>of</strong> the unfaithful wife, a practice<br />

General Crook had strictly forbidden. They insisted he had no<br />

business interfering with their customs. The other was the<br />

drinking <strong>of</strong> tiswin, a beer made <strong>of</strong> fermented corn. Mangus’s<br />

wife was a maker <strong>of</strong> excellent tiswin and she hated Whites. She<br />

goaded her husband, the son <strong>of</strong> the legendary chief, Mangas<br />

Colorados, constantly. Chihuahua was one <strong>of</strong> her best customers.<br />

He liked to drink and complain but wasn’t too interested in<br />

bolting the reservation again. The consummate malcontent<br />

Geronimo took advantage <strong>of</strong> the situation to stir up trouble.<br />

In May, 1885, a group <strong>of</strong> Apache decided to test the policy<br />

against tiswin. They got drunk and confronted the <strong>of</strong>ficer in<br />

charge, Lieutenant Britton Davis. Davis informed them he was<br />

wiring General Crook for instructions. The wire was sent to a<br />

Captain Francis Pierce; an <strong>of</strong>ficer new to the area failed to<br />

grasp the gravity <strong>of</strong> the situation and determined it wasn’t important<br />

enough to bother the general. Meanwhile, the Apache<br />

grew restless wondering what kind <strong>of</strong> wrath the general would<br />

bring upon them for their drunken binge and bolted once again<br />

for Mexico.<br />

Thus began the last campaign to end the Apache Wars. In<br />

January, 1886, Captain Emmett Crawford defeated Geronimo

and band in the Sierra Madre. Two months later the Apache<br />

leader met with General Crook at Canon de los Embudos, and<br />

agreed to surrender. Thus began the last campaign to end the<br />

Apache Wars. In January, 1886, Captain Emmett Crawford<br />

defeated Geronimo and band in the Sierra Madre. Two months<br />

later the Apache leader met with General Crook at Canon de los<br />

Embudos, and agreed to surrender. That night bootleggers<br />

came into the Apache camp and sold them booze, at the same<br />

time telling them the soldiers planned to kill them once they<br />

were in Arizona.<br />

Geronimo and warriors bolted once again causing Crook’s<br />

superior in Washington, General Phil Sheridan, also his roommate<br />

at West Point, to suggest he was placing too much trust in<br />

the Apache. Crook asked to be replaced and General Nelson<br />

Miles was sent to relieve him.<br />

Camels in the Southwest Desert?<br />

Photograph and story by Marshall Trimble, Official Arizona<br />

State Historian<br />

Arizona has always been a place where bizarre events were<br />

accepted as normal. But perhaps the strangest <strong>of</strong> all occurred in<br />

1857 when a caravan <strong>of</strong> camels looking like something out <strong>of</strong><br />

the Arabian Nights trekked across northern Arizona.<br />

At the time, the federal government was planning to survey<br />

a wagon road along the 35 th Parallel from New Mexico to California<br />

and wanted to test the feasibility <strong>of</strong> using camels as<br />

beasts <strong>of</strong> burden. The camel experiment was the pet project <strong>of</strong><br />

Secretary <strong>of</strong> War, Jefferson Davis, who believed that camels<br />

were the solution for transporting cargo across the arid lands <strong>of</strong><br />

the American West.<br />

The man chosen to lead the experiment was a colorful adventurer<br />

named Lieutenant Edward F. “Ned” Beale <strong>of</strong> the Army<br />

Corps <strong>of</strong> Topographical Engineers. Beale, a former Navy <strong>of</strong>ficer,<br />

had been a hero at the Battle <strong>of</strong> San Pasquel in California<br />

during the Mexican war when he and Kit Carson sneaked<br />

through the enemy lines to bring a relief force from San Diego<br />

to General Kearny’s Army <strong>of</strong> the West, under siege by Mexican<br />

forces.<br />

Following the discovery <strong>of</strong> gold in California in 1848, Beale<br />

took a sack full <strong>of</strong> gold nuggets and traveled across Mexico<br />

disguised as a Mexican. He eventually reached Washington<br />

D.C. and presented the gold to President James Polk, proving<br />

that rumors <strong>of</strong> the gold strike in California were indeed true.<br />

Courier page 5<br />

The campaign was nearly over by the time Miles arrived.<br />

He continued Crook’s policy <strong>of</strong> using Apache scouts, durable<br />

pack trains and relentless pursuit. The Army also rounded up<br />

the Chiricahua on reservations and shipped them to Florida.<br />

That summer five thousand U.S. troops or some 20% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

U.S. Army were chasing less than two dozen warriors. In August<br />

Lieutenant Charles Gatewood, an <strong>of</strong>ficer known and respected<br />

by Geronimo, Tom Horn, along with two Apache<br />

scouts named Martine and Kayitah undertook a dangerous mission<br />

to Geronimo’s camp. They held a parley with Geronimo<br />

and his band. After some haggling, Gatewood dealt the warriors<br />

his ace card. Their relatives had been exiled to Florida and<br />

if they wanted to see them again they would have to surrender.<br />

On September 3, 1886, the wily war chief surrendered and the<br />

Apache Wars were finally over.<br />

Beale’s Camel expedition nearly a decade later was<br />

unique<br />

in the annals <strong>of</strong> exploration in the American West. The<br />

camel’s amazing ability to travel great distances without<br />

water, and thriving on natural forage along the trail made<br />

them a natural for hauling cargo.<br />

Although Beale championed his illustrious camels, referring<br />

to them as the “noblest brute alive,” his muleskinners<br />

scorned them. They were especially upset when entire<br />

herds <strong>of</strong> mules stampeded at the mere site <strong>of</strong> the homely<br />

creatures. The camels propensity to be extremely stubborn<br />

and spit at the muleskinners certainly didn’t endear them to<br />

their American handlers. The problem handling the animals<br />

was solved when camel drivers were imported from the<br />

Middle East. A Syrian named Hadji Ali was the most famous.<br />

His name was quickly Americanized to “Hi Jolly.”<br />

The camels passed a supreme test when Beale was challenged<br />

to pit them against the packers’ mules on a 60-mile endurance<br />

trek. Using six camels against twelve mules, a 2.5 ton<br />

load was divided among the camels, and a like amount was<br />

loaded on two Army wagons, drawn by six mules. The camels<br />

finished the trip in two and a half days while the mules took<br />

four days.<br />

Beale and his camels managed to successfully open the<br />

wagon road along the 35 th Parallel. That road later became the<br />

storied Route 66 and is today Interstate 40. He persisted in<br />

naming the various rivers, passes and mountains after his fellow<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers in the U.S. Navy. The names usually didn’t stick and if<br />

they had, most <strong>of</strong> the geographical features in western Arizona<br />

would today sound like a battleship’s roster.<br />

Hi Jolly remained in Arizona, got married and became a<br />

prospector. He is memorialized on a pyramid-shaped monument,<br />

topped <strong>of</strong>f with a lone camel, at Quartzsite, Arizona.<br />

This brief, but romantic event in Arizona history came to an<br />

end just before the Civil War began and was overshadowed by<br />

the great events that took place in the East. As for the camels,<br />

they were turned loose to roam the deserts <strong>of</strong> western Arizona.<br />

One, “Red Ghost,” became the stuff <strong>of</strong> legends. When pranksters<br />

tied a dead body on his back the animal went insane and<br />

attacked a woman, killing her. Over the next few years the<br />

camel, with a skeleton tied to its back, was seen at various parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arizona, causing havoc when it came around humans and<br />

became the subject <strong>of</strong> many a campfire story.

Courier page 6<br />

By Trudie Cooke<br />

By Trudie Cooke<br />

Down Range: To<br />

Iraq and Back<br />

speaks to the hearts<br />

<strong>of</strong> our <strong>military</strong> men<br />

and women<br />

Down Range: To Iraq and Back, by Bridget C. Cantrell,<br />

Ph.D. and Chuck Dean, Word Smith Publishing, Seattle, WA<br />

98168, 2005, is a small paperback book that <strong>of</strong>fers help to all<br />

the men and women who have served in combat.<br />

This book is a surprise in such a compact form. The message<br />

is timely, and to some veterans <strong>of</strong> past wars, long overdue.<br />

Down Range is dedicated to bringing the troops home and addresses<br />

the challenges <strong>of</strong> the re-integration process from combatant<br />

to civilian.<br />

On the back cover is written, “Bridget Cantrell, Ph.D. and<br />

Vietnam veteran, Chuck Dean have joined forces to present this<br />

vital information and resource manual for both returning troops<br />

and their loved ones. Here you will find answers, explanations,<br />

and insights as to why so many combat veterans suffer from<br />

flashbacks, depression, fits <strong>of</strong> rage, nightmares, anxiety, emotional<br />

numbing, and other troubling aspects <strong>of</strong> Post-Traumatic<br />

Stress Disorder (PTSD).”<br />

The Springfield 1903 Rifle and<br />

those daring Bushmasters<br />

An interesting comment on the famed Bushmaster’s M1903<br />

rifle used during World War II:<br />

Briefly, the 158th Infantry became the 158th Regiment<br />

Combat Team and separated from the 45th Division <strong>of</strong> Oklahoma<br />

on Sep 16, 1940. They spent a year in the Panama Canal<br />

Zone where they earned their nickname “Bushmasters.” By Jan<br />

16, 1943, they were at Port Moresby, New Guinea. They remained<br />

in the Philippines for the remainder <strong>of</strong> the war.<br />

They were equipped with the M1903 Springfield rifle prior<br />

to departure for the Panama Canal Zone. While in the Canal<br />

Zone , they modified their issued M1903 rifle. Lt. Col. William<br />

S. Brophy, USAR, Ret., says in his book The Springfield 1903<br />

Rifles, (1985), “Frequently brave souls in the <strong>military</strong> perform<br />

unauthorized modifications to standard equipment. However,<br />

the fear <strong>of</strong> the discipline meted out, and the possible attachment<br />

<strong>of</strong> pay for the cost <strong>of</strong> the item, prevented many worthwhile and<br />

inventive ideas from being tried….However, if high authority<br />

blessed the project, it was not uncommon for ideas to be tried<br />

and, in some cases, put to use….A good example <strong>of</strong> equipment<br />

Some excepts from the book are:<br />

“War forces its participants to go beyond the paradigms <strong>of</strong><br />

ordinary life, pushing them beyond what one would think are<br />

humanly possible. When we assertively take the life <strong>of</strong> another<br />

human being we are catapulted far beyond the range <strong>of</strong> normal<br />

human behavior. As terrible as killing is, it is still not the worst<br />

outcome <strong>of</strong> war. Cruelty to the souls <strong>of</strong> the soldiers who fight<br />

is war’s greatest casualty….<br />

At the end <strong>of</strong> each battle, and when the war is over, the images<br />

and sounds <strong>of</strong> combat are still present in the minds and<br />

hearts <strong>of</strong> those who engaged in it—and these will never go<br />

away….Now comes the full realization that you willingly participated<br />

in something so unnatural to the mind and<br />

spirit” (page 24 and 25).<br />

“We should never again blame the individual soldiers (like<br />

so many did during the Vietnam War) for fighting in a war that<br />

was decided upon by government leaders” (page 25).<br />

This book also provides contact sources for help that include<br />

such places as the Veterans Administration, the Vietnam<br />

Veterans <strong>of</strong> America, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline,<br />

the National Veterans Foundation, and many other groups that<br />

specifically handle PTSD.<br />

The whole point <strong>of</strong> this book is to be an educational guide, a<br />

spiritual guide, a source guide—all rolled into one small paperback<br />

book. The warrior and his family are not alone. Help is<br />

out there.<br />

This book may be obtained from the Arizona National<br />

Guard Personnel Readiness Center, Frank Sandell, Transition<br />

Assistance Advisor, Papago Park Military Reservation, 5636 E<br />

McDowell Rd, Phoenix, AZ 85008 at 602-629-4421. It is free<br />

while supplies last.<br />

for a particular use in a specific area is the Bushmaster ’03 rifle.”<br />

(page 82)<br />

“By order <strong>of</strong> Major General Robert H. Lewis, Commanding<br />

General <strong>of</strong> the Panama Mobile Force Command in 1942, Model<br />

1903 rifles were shortened six inches for use by the Jungle Security<br />

Platoon [the Bushmasters] while conducting missions in<br />

heavy jungle foliage.” (page 83)<br />

Alterations were done by the Ordnance Shops in the Canal<br />

Zone once permission was granted by the Army Chief <strong>of</strong> Ordnance.<br />

The altered M1903 was used by the Bushmasters in the<br />

Canal Zone and also in the Philippines.<br />

From The Springfield 1903 Rifle, William S. Brophy, 1985,<br />

page 82.

The 1st Arizona Infantry fights Apaches:<br />

Arizona Indian Wars 1865 to 1866<br />

By Jim Turner, Historian for the Arizona Historical<br />

Society—Tucson, AZ<br />

(Editor’s note: With the Civil War still going on<br />

and Carleton still fighting the Navajos, the U.S. War<br />

<strong>Department</strong> authorized Governor John Noble Goodwin<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arizona to raise five companies <strong>of</strong> Arizona<br />

Volunteers in 1864. Recruitment was delayed for a<br />

year, but by the fall <strong>of</strong> 1865, more than 350 men had<br />

been issued into service under the command <strong>of</strong> nine<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers. The overwhelming majority was Mexicans,<br />

many <strong>of</strong> them from Sonora, or O'odham and Maricopas<br />

from the Gila River villages, who had grown up<br />

fighting Yavapais and Apaches, as had their fathers<br />

and grandfathers. Many never received shoes or<br />

warm clothing. They lived in hovels and marched for<br />

days on beef jerky and parched cornmeal. They carried<br />

.54-caliber (14 mm) rifles with plenty <strong>of</strong> ammunition,<br />

in addition to bows, arrows, and war clubs.<br />

For the next year, these frontiersmen guarded wagon<br />

trains between Prescott and La Paz and campaigned<br />

relentlessly across central Arizona. The following<br />

excerpt and description <strong>of</strong> the 1 st Arizona Volunteer<br />

Infantry was presented by Jim Turner, Historian for<br />

the Arizona Historical Society—Tucson—in an article,<br />

“Pima Villages”, the Journal <strong>of</strong> Arizona History<br />

1998. The article was too lengthy to include in the<br />

Courier, but we highly recommend that the reader<br />

seek out and read the entire article to learn some<br />

important Arizona history.)<br />

Governor John N. Goodwin, 1863—1866, received<br />

permission from the United States Provost<br />

Marshal James B. Fry to “raise within the Territory<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arizona one regiment <strong>of</strong> Volunteer Infantry to<br />

serve for three years or the duration <strong>of</strong> the war.” The<br />

War <strong>Department</strong> intended that the recruitment <strong>of</strong> native<br />

Arizonans would supplement the California Volunteers,<br />

who hesitated to go on long scouting missions<br />

against the Apaches because their Civil War<br />

enlistment would soon be up. The Arizona Volunteers<br />

served for one year, and gave Mexicans, Pimas<br />

and Maricopas an opportunity to avenge the losses<br />

they received at the hands <strong>of</strong> the Apaches while acquiring<br />

much-needed guns from the government.<br />

Courier page 7<br />

Goodwin appointed Thomas Ewing, a teamster<br />

from the Pima Villages, to recruit Maricopa Indians,<br />

and former sergeant John D. Walker to recruit the<br />

Pimas. (This is not the same John Walker who was<br />

previously Indian Agent.) On October 2, 1865, First<br />

Lieutenant William Tompkins <strong>of</strong> the Third California<br />

Infantry arrived at Maricopa Wells and commissioned<br />

First Lieutenant Ewing, Second Lieutenant<br />

Charles Reidt, who was fluent in the Maricopa language,<br />

and Captain Juan Chevereah, chief <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Maricopas. He also mustered in 94 Maricopa recruits,<br />

designated as Company B, Arizona Volunteer<br />

Infantry. By May 16, 1866 there were 103 men in the<br />

company. John D. Walker was commissioned as first<br />

lieutenant and William A. Hancock as second lieutenant<br />

<strong>of</strong> Company C, made up <strong>of</strong> Pima Indians.<br />

Their chief, Antonio Azul, was made a sergeant and<br />

89 Pimas were recruited to fill out the company. Five<br />

more Pimas were added later at Sacaton.<br />

A unique Arizona character, John D. Walker was<br />

part Wyandotte Indian, born in Nauvoo, Illinois<br />

about 1840. He arrived at the Pima villages as a<br />

wagon master in the California Volunteers, and was<br />

charged with expediting the distribution <strong>of</strong> the Pimas’<br />

surplus wheat and corn to California Volunteer<br />

posts as far away as the Rio Grande. When his enlistment<br />

was up, Walker married a Pima woman and<br />

settled in the Pima village <strong>of</strong> Sacaton. Quick to learn,<br />

he compiled the first written grammar <strong>of</strong> their language<br />

and became a leader in Pima councils. He<br />

studied medicine and was something <strong>of</strong> a scientist.<br />

Such a background makes the other side <strong>of</strong> his character<br />

even more unusual. According to historian<br />

James McClintock, "It is said that when they were in<br />

the field you could not tell him from the other Indians.<br />

He dressed like them, with nothing but a breechcloth,<br />

and whooped and yelled like his Indian comrades."<br />

The native Arizonans enlisted just as Apache raiding<br />

reached new heights, and their orders — to destroy<br />

Apache camps, crops and supplies and kill resisters<br />

— coincided with their attitudes toward their<br />

traditional enemies. The Indian soldiers received a<br />

blue blouse, trimmed in red for the Maricopas and<br />

blue for the Pimas, one pair <strong>of</strong> blue pants, one pair <strong>of</strong><br />

shoes and one yard <strong>of</strong> flannel for a headdress. Most

Courier page 8<br />

<strong>of</strong> them wore “teguas” — shoes <strong>of</strong> untanned hide<br />

with broad soles turned up at the toes with a hole to<br />

admit air and remove dirt. Scouts were <strong>of</strong>ten carried<br />

out on foot with packs containing a canteen, a blanket,<br />

and some dried beef and pinole, a food made <strong>of</strong><br />

one part sugar to two parts roasted ground corn or<br />

wheat mixed with water. The Indians were expected<br />

to provide their own horses, but allowances were<br />

sometimes made for feed. Although these were the<br />

intended provisions, circumstances did not always<br />

afford them and the Indians <strong>of</strong>ten endured the cold<br />

without benefit <strong>of</strong> warm clothes, bedding or shoes.<br />

The Pimas and Maricopas were used to hardship,<br />

however; they were familiar with the country and<br />

knew the Apaches.<br />

The two new volunteer companies left Maricopa<br />

Wells with Colonel Clarence E. Bennett’s California<br />

Volunteers on September 4, 1865 to establish a fort<br />

seven miles north <strong>of</strong> the confluence <strong>of</strong> the Verde and<br />

Salt rivers. Both companies helped construct Camp<br />

McDowell to protect farms along the rivers from<br />

Apaches. The Tonto and Pinal Apaches inhabited the<br />

Tonto Basin, bordered by the Mazatzal and Sierra<br />

Ancha Mountains on the east and west and the<br />

Mogollon Rim to the north. These were some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

last Apache tribes to be subdued, and the Arizona<br />

Volunteers became their first considerable foe. The<br />

Indians at Camp McDowell lived in brush shelters.<br />

Military reports said their morale was high and they<br />

were allowed to return to their villages almost as <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

as they pleased. Although Hispanic and Anglo<br />

volunteers suffered various forms <strong>of</strong> typhoid from<br />

continuous attacks <strong>of</strong> fever caused by rain and humidity,<br />

not a single individual from Indian companies<br />

B or C was reported sick on post returns.<br />

The Indian volunteers began their first foray on<br />

September 8, 1865, led by Lieutenant Reidt. They<br />

traveled northeast for several days into the Tonto Basin.<br />

Maricopa guides took them up the east side <strong>of</strong><br />

the Mazatzal Mountains up Tonto Creek, 110 miles<br />

up steep banks, across canyons, and through arroyos<br />

thick with underbrush. “It was a trying, sorry march,<br />

and the animals and men suffered from the cactus.”<br />

When one Pima was accidentally shot in the hand, all<br />

but fifteen returned to camp with him. The volunteers<br />

eventually surprised an Apache ranchería just<br />

east <strong>of</strong> Payson. One Apache was killed, several were<br />

wounded and their crops and houses were burned.<br />

The Indian volunteers proved their valor in battle<br />

after battle. On October 15, 1865, Cuchavenashak,<br />

a Company B Maricopa charged an Apache. The<br />

Apache's first arrow went through his horse's ear, the<br />

second hit the Maricopa's belt plate and the third hit<br />

him in the forehead and glanced <strong>of</strong>f, causing a flesh<br />

wound. Cuchavenashak leaped <strong>of</strong>f his horse,<br />

clinched the Apache to him and killed him. This<br />

alarmed a ranchería <strong>of</strong> about 20 families <strong>of</strong> Apaches<br />

nearby. A volley <strong>of</strong> 100 shots were fired into the<br />

Apaches as they retreated.<br />

The Arizona Volunteers were an experiment in<br />

cultural coexistence. For the good <strong>of</strong> the mission, the<br />

Indians were allowed to practice their traditional war<br />

customs without interference from white soldiers. On<br />

March 6, 1866, Lt. Ewing took a party near the Polos<br />

Blancos [sic] Mountains, on Rattlesnake Creek “The<br />

night being quite dark, it was decded to await the rising<br />

<strong>of</strong> the moon. During the wait, the Indian soldiers<br />

consulted a prophet or tobacco mancer. A circle was<br />

formed around the prophet who began to smoke<br />

"cigarettes." As soon as one was consumed another<br />

was furnished him by an attendant. After some time,<br />

he began to tremble and fell "dead" (stupefied). He<br />

lay there for several minutes, during which time not<br />

a sound was heard from command. When he arose,<br />

he said that his spirit had followed the trail, that the<br />

command was on, towards the "Massasahl" and there<br />

under the peak it saw two large rancherías with a<br />

great many warriors. His spirit then followed the trail<br />

north, where it found a ranchería that had been abandoned<br />

because <strong>of</strong> the death <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the occupants.”<br />

When he finished, the Indians slept. When the moon<br />

had risen high in the sky, Walker and Ewing led their<br />

men up the mountain in search <strong>of</strong> the ranchería.

Halfway up the mountain they found an abandoned<br />

ranchería and later a large camp <strong>of</strong> Apaches, just as<br />

the tobacco mancer predicted.<br />

On March 27, Lieutenant Walker led the largest<br />

expedition <strong>of</strong> Arizona Volunteers on record; an estimated<br />

260 Papagos and Pimas and 40 Maricopas<br />

from Company B left the Pima villages. Those from<br />

Company B left the Pima villages. Those without<br />

rifles or muskets fashioned war clubs while they established<br />

a temporary supply depot on Tonto Creek.<br />

In a fight four days later, 25 Apaches were killed and<br />

16 taken prisoner. Three Pimas were wounded, one<br />

<strong>of</strong> whom eventually died. Because they were in<br />

Apache country, the Pima warrior’s body was burned<br />

along with the mourners’ clothes instead <strong>of</strong> his own<br />

belongings as was the custom in the villages. Although<br />

most warriors left the Pima villages well clad,<br />

many returned naked. This is also probably the expedition<br />

where the miners were shocked by the smashing<br />

<strong>of</strong> heads. Conner relates that the Pimas would lift<br />

a heavy stone above their heads and drop it on a dead<br />

or wounded Apache, crushing the skull <strong>of</strong> their enemy.<br />

Sometimes they placed the head <strong>of</strong> the victim<br />

on a flat rock to suitably cave in his face, perhaps so<br />

it would not be recognized in the next world. The<br />

Apaches, possibly learning it from the Pimas, followed<br />

this custom. Conner said he was more disgusted<br />

that the Whites looked on with approval, musing<br />

that “savage civilized men are the most monstrous<br />

<strong>of</strong> all monsters.”<br />

In late Aug, 1866, Colonel Charles S. Lovell became<br />

commander <strong>of</strong> District <strong>of</strong> Arizona. He did not<br />

appreciate the Pima and Maricopa custom <strong>of</strong> living<br />

in their villages when not in the field and not being<br />

subject to the post commanders’ orders. General Mason<br />

had promised the Indians that they could do as<br />

they pleased, and the spirit <strong>of</strong> cooperation had served<br />

all parties admirably. As was <strong>of</strong>ten the case with<br />

army/Indian relations, just as the vastly different cultures<br />

began to understand each other, personnel<br />

changed, previous arrangements were nullified and<br />

once again the Indians had to adapt. Official feelings<br />

were not unanimous on the subject <strong>of</strong> Indian soldiers,<br />

however. In May, while still commander at Fort<br />

McDowell, Colonel Bennett asked the Arizona’s Adjutant<br />

General to extend the volunteer enlistment or<br />

create a regular native regiment. If these options<br />

proved unworkable, he proposed that the volunteers<br />

be allowed to keep their arms when discharged so<br />

they could continue fighting Apaches effectively.<br />

Courier page 9<br />

1907 Portrait <strong>of</strong> Antonio Azul, last hereditary chief <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Pima Indians. Died at Sacaton, AZ, October 20, 1910 at<br />

the age <strong>of</strong> about 76. He was a 2nd Lieutenant, 1st Arizona<br />

Infantry, Company C, National Guard <strong>of</strong> Arizona<br />

during the 1866 Indian Wars. Photograph courtesy <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Pima-Maricopa Indian Community.<br />

At Fort McDowell on September 11, 1866, because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the legalities <strong>of</strong> retaining them, Maricopa<br />

Company B was discharged from service by First<br />

Lieutenant Ewing and now Captain Juan Chevereah.<br />

The records indicated that Maricopas McGill, Yose,<br />

Goshe Zep, and Duke were killed in battle. The same<br />

day, Pima Company C was mustered out by Captain<br />

John D. Walker. Hownik Mawkum, Juan Lewis and<br />

Au Papat were Pimas listed as killed in battle. All the<br />

men were allotted $50 pay and allowed to keep their<br />

firearms and equipment. Many volunteers who believed<br />

they would get no pay found that all at once<br />

they had more money than they had ever had at any<br />

time in their lives. In honor <strong>of</strong> the Arizona Volunteers,<br />

in the fall <strong>of</strong> 1866 the Third Arizona Territorial<br />

Legislature passed a memorial for their outstanding<br />

service.<br />

The services <strong>of</strong> Arizona Volunteers were definitely<br />

missed. In November <strong>of</strong> 1866, General<br />

McDowell let it be known that any Indians enlisting<br />

as scouts would be treated as when they served in the<br />

Volunteers. They would not be required to drill or<br />

fight with army methods and could stay in their villages<br />

when not on patrol. Pimas and Maricopas continued<br />

to work with the <strong>military</strong>, but the practice<br />

peaked in 1869 as more Apaches became willing to<br />

serve as scouts.

Courier page 10<br />

Buffalo Soldiers served in Arizona during the Indian Wars <strong>of</strong> 1888<br />

By John Langellier, Director, Shalot Hall Museum, Prescott,<br />

AZ<br />

Last February at the Museums<br />

on the Mall event, I was<br />

talking to John Langellier,<br />

Director, Sharlot Hall Museum,<br />

about the actions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Buffalo Soldiers in Arizona. I<br />

told him that some people told<br />

me that they never were in<br />

Arizona during the Indian<br />

Wars era. John, who is an<br />

expert <strong>military</strong> historian, said<br />

he would send me some information.<br />

Here is what he sent:<br />

The 10th U.S. Cavalry<br />

regiment transferred from the<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Texas to the<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Arizona in 1886 with the regimental headquarters<br />

at Ft. Whipple under Colonel Benjamin Grierson<br />

and the various companies assigned to forts all over the<br />

territory including Forts Apache and Grant. The 10th participated<br />

in the final Apache campaigns, and the name<br />

“Buffalo Soldiers” first appeared in print for a widespread<br />

audience when Fredrick Remington wrote and illustrated<br />

an article in Arizona in 1888 titled “Scout with the Buffalo<br />

Soldiers.” The 24th Infantry also reported to Arizona<br />

soon aft the arrival <strong>of</strong> the 10th, and two <strong>of</strong> their men received<br />

the Medal <strong>of</strong> Honor for the incident cited below.<br />

Thus, black troops have been stationed continuously in<br />

Arizona since 1886 and continue to play a role in the<br />

armed forces here to this day.<br />

He also sent a story written by Paul L. Allen published<br />

in the Arizona Republic on July 29, 2006:”Lookin' Back:<br />

Safford-area Treasury Ambush Stuff <strong>of</strong> Legends”:<br />

When you mix an audacious crime with goodly a<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> loot and a sizable dollop <strong>of</strong> whodunit, you've<br />

got a ready-made Old West legend.<br />

Such is the Wham payroll robbery <strong>of</strong> May 11, 1889,<br />

which bears the added distinction <strong>of</strong> being likely the most<br />

frequently mispronounced incident name in the Southwest.<br />

It is pronounced Wham (like "bomb") and not<br />

Wham (like "Bam!").<br />

Here's what happened:<br />

Army Maj. Joseph W. Wham and an escort <strong>of</strong> 11 Buffalo<br />

Soldiers from the 24th Infantry and 10th Cavalry were en<br />

route from Fort Grant to Fort Thomas, but northwest <strong>of</strong><br />

present-day Safford on the Gila River.<br />

Wham rode in an ambulance that also carried a strongbox<br />

containing $28,345 in gold and silver coins, much <strong>of</strong><br />

it still in Treasury <strong>Department</strong> sacks. An escort wagon<br />

followed the ambulance.<br />

They were forced to stop at Cedar Springs because a<br />

large boulder blocked the roadway<br />

where it passed through a<br />

narrow defile. Men in the escort<br />

set about moving the obstacle,<br />

but were immediately<br />

fired upon from both sides <strong>of</strong><br />

the road. Eight were wounded<br />

in the melee.<br />

Their attackers numbered -<br />

depending on whose account is<br />

to be believed - from eight to<br />

20.<br />

Wham, in reporting the incident<br />

to the Secretary <strong>of</strong> War,<br />

wrote that the "party was am-<br />

“Proud to Serve,” oil painting by Don Stivers, Waterford, VA,<br />

bushed and fired into by a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> armed brigands, since<br />

estimated by U.S. Marshal (W.K.) Meade at from twelve<br />

to fifteen, but to myself and entire escort, two noncommissioned<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers and nine privates, at fifteen to<br />

twenty."<br />

He indicated a signal shot was followed by a barrage<br />

<strong>of</strong> gunfire, and a battle lasting more than 30 minutes ensued.<br />

Two soldiers involved, one shot in the abdomen but<br />

continuing to fire until shot again through both arms, and<br />

another who, though wounded, walked and crawled<br />

nearly two miles to Cottonwood Ranch to give the alert,<br />

later were awarded the Medal <strong>of</strong> Honor.<br />

The rancher who brought some <strong>of</strong> his cowboys to the<br />

scene <strong>of</strong> the battle arrived after the attackers had fled with<br />

the loot. They sent a <strong>courier</strong> to Fort Thomas to alert the<br />

commander, and a surgeon and hospital ambulance were<br />

dispatched to tend the wounded.<br />

Lt. Powhattan H. Clarke and detachments from Troop<br />

K, 10th Cavalry, and Company I, 24th Infantry, went in<br />

pursuit <strong>of</strong> the attackers.* Eventually eight suspects<br />

(another account indicates nine) were identified and arrested--all<br />

Mormon ranchers and farmers from the Safford<br />

area. The missing money was not found.<br />

At the trial convened Nov. 11, 1889, in Tucson, they<br />

were defended by attorney Marcus Aurelius Smith, a colorful<br />

attorney and perennial congressional delegate Ben<br />

Goodrich, and Frank Hereford. Prosecution attorneys included<br />

U.S. Attorneys Harry Jeffords, William Herring,<br />

Herring's Tucson-based son-in-law Selim M. Franklin.<br />

(Both Hereford and Franklin were members <strong>of</strong> Tucson's<br />

bachelor enclave known as "the Owls.")<br />

The defense attorneys worked to attribute blame to a<br />

dozen unidentified drifters alleged to have been in the<br />

area at the time <strong>of</strong> the robbery. It is likely, the jury was

told, that they escaped into Mexico with the purloined<br />

payroll.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> the confusion during the battle, neither<br />

Wham nor any <strong>of</strong> his escort troops were able to identify<br />

any <strong>of</strong> the defendants in court, and after a marathon 33day<br />

parade <strong>of</strong> courtroom histrionics, the defendants were<br />

acquitted.<br />

Hearsay <strong>of</strong> the time indicated all those charged were<br />

on good terms with the acting territorial governor, and<br />

that he exerted political pressure to have them acquitted.<br />

The Wham payroll robbery has become an enduring<br />

legend in the Safford area and beyond, with some insisting<br />

the accused were, indeed, innocent, and others noting<br />

that times were hard in the area in 1889, and that government<br />

money would have provided welcome relief.<br />

Wham died Dec. 21, 1908, in Washington, D.C., and<br />

is buried at Wham Hill Cemetery, Marion County, Ill.<br />

*This is the same Second Lieutenant Powhattan H.<br />

Clarke, Company K and who received the Medal <strong>of</strong><br />

Honor for rescuing Corporal Scott while under heavy fire<br />

from Apaches at Pinito Mountains, Sonora, Mex., 3 May<br />

1886. Entered service at: Baltimore, Md. Birth: Alexandria,<br />

La. Date <strong>of</strong> issue: 12 March 1891. Citation: Rushed<br />

forward to the rescue <strong>of</strong> a soldier who was severely<br />

wounded and lay, disabled, exposed to the enemy's fire,<br />

and carried him to a place <strong>of</strong> safety.<br />

According to the June 15, 2007 “An Arizona Buffalo<br />

Soldier,” Arizona Capitol Times article, Lt. Powhatan H.<br />

Clarke referred to the soldiers <strong>of</strong> the black 10th Cavalry<br />

Regiment under his command by racially derogatory<br />

names. However, at the same time he wrote, “No men<br />

could have been more determined and cooler.” A commander<br />

in the Civil War, he met his end in the most famous<br />

Indian battle in American history. His death at the<br />

Little Bighorn might have prevented him from becoming<br />

the only goat to be elected president <strong>of</strong> the United Stares.<br />

Pickett, <strong>of</strong> course, has his name attached to one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world's most famous charges.<br />

Much thanks to John for this colorful information<br />

which helps put history in perspective and helps me win<br />

arguments with people who think they know Arizona’s<br />

<strong>military</strong> history when they don’t. The Director<br />

8 November 2008<br />

9am to 4pm<br />

Come visit us at the Arizona Military<br />

Museum<br />

Displays <strong>of</strong> <strong>military</strong> vehicles, artifacts from<br />

the <strong>museum</strong>, and books for sale.<br />

Bring your children and grand-children to see<br />

the old vehicles and weapons.<br />

Enjoy Veterans Day With Us!<br />

Survival<br />

By Anonymous (worldwide web)<br />

Courier page 11<br />

Some Thoughts about Survival, Firearms, and Protecting<br />

Yourself<br />

This is the law:<br />

The purpose <strong>of</strong> fighting is to win.<br />

There is no possible victory in defense.<br />

The sword is more important than the shield;<br />

skill is more important than either.<br />

The final weapon is the brain.<br />

All else is supplemental.<br />

These are the rules:<br />

1. Don't pick a fight with an old man. If he is too old to<br />

fight, he will just kill you.<br />

2. If you find yourself in a fair fight, your tactics suck.<br />

3. I carry a gun 'cause a cop is too heavy.<br />

4. America is not at war. The U.S. Military is at war.<br />

America is at the Mall.<br />

5. When seconds count, the cops are just minutes away.<br />

(Yep, shoot first, then call 911)<br />

6. A reporter did a human interest piece on the Texas<br />

Rangers. The reporter recognized the Colt Model 1911 the<br />

Ranger was carrying and asked him "Why do you carry<br />

a .45?" The Ranger responded with, “Because they don't<br />

make a 46."<br />

7. The old sheriff was attending an awards dinner when a<br />

lady commented on his wearing his sidearm. "Sheriff, I<br />

see you have your pistol. Are you expecting trouble?"<br />

"No Ma'am", answered the Sheriff. "If I were expecting<br />

trouble, I would have brought my rifle." (Winchester<br />

Model 94, 30-30 Cal. and loaded with Winchester Silver<br />

Tips, no doubt.)<br />

8. Beware the man who only has one gun.... HE PROBA-<br />

BLY KNOWS HOW TO USE IT!!!<br />

Some thoughts about being armed:<br />

I was once asked by a lady visiting if I had a gun in the<br />

house. I said "I did." She said, "Well I certainly hope it<br />

isn't loaded!" To which I said, "Of course it is loaded."<br />

She then asked, "Are you that afraid <strong>of</strong> someone evil coming<br />

into your house?" My reply was, "No, not at all. I am<br />

not afraid <strong>of</strong> the house catching fire either, but I have fire<br />

extinguishers around, and THEY ARE ALL LOADED,<br />

TOO."

Courier page 12<br />

Editorial:<br />

America’s Global War on Terrorism:<br />

Success or Failure<br />

By Joseph Abodeely, Director<br />

For several years, America has been engaged in what<br />

has been called the “Global War On Terrorism” (GWOT).<br />

The cost in lives and treasure has been tremendous, and<br />

other tangential costs to America in loss <strong>of</strong> international<br />

prestige, the devaluation <strong>of</strong> the dollar, the decline <strong>of</strong> the<br />

economy, the diversion <strong>of</strong> attention to preserving the U.S.<br />

infrastructure, and the over taxing <strong>of</strong> American armed<br />

forces and related resources—all have a negative impact<br />

on U.S. national security. Since September 11, 2001,<br />

more than 4,600 Arizona National Guard soldiers and<br />

airmen have been ordered to federal active duty in support<br />

<strong>of</strong> Operation Noble Eagle, Enduring Freedom, and Iraqi<br />

Freedom. It is essential that the American public and<br />

those whose duty it is to combat “terrorism” truly understand<br />

what it is.<br />

The RAND Corporation is a nonpr<strong>of</strong>it research organization<br />

providing objective analysis and effective solutions<br />

that address the challenges facing the public and private<br />

sectors around the world. RAND's publications do not<br />

necessarily reflect the opinions <strong>of</strong> its research clients and<br />

sponsors. Recently, the RAND Corporation presented a<br />

monograph relating to a study <strong>of</strong> how terrorist organizations<br />

reached their demise. This research in the public<br />

interest was supported by RAND, using discretionary<br />

funds made possible by the generosity <strong>of</strong> RAND's donors,<br />

the fees earned on client-funded research, and independent<br />

research and development (IR&D) funds provided by<br />

the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Defense. All RAND monographs undergo<br />

rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for<br />

research quality and objectivity.<br />

For those who believed that the so-called GWOT was<br />

ill-conceived and ill-implemented—not because <strong>of</strong> pacifistic<br />

tendencies or political motives—but from a clearer<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> the nature <strong>of</strong> the threat <strong>of</strong> “terrorism”<br />

than the political slogans which persuaded the majority <strong>of</strong><br />

the American public to believe, the RAND monograph<br />

entitled, How Terrorist Groups End: Lessons for Countering<br />

al Qa'ida, by Seth G. Jones and Martin C. Libicki,<br />

is vindication. The full monograph can be obtained<br />

online by Googling RAND Corporation, but the salient<br />

points in summary about the monograph follow.<br />

The research showed that all terrorist groups eventually<br />

end. But how do they end? The evidence since 1968<br />

indicates that most groups have ended because (1) they<br />

joined the political process (43 percent) or (2) local police<br />

and intelligence agencies arrested or killed key members<br />

(40 percent). Military force has rarely been the primary<br />

reason for the end <strong>of</strong> terrorist groups, and few<br />

groups within this time frame have achieved victory.<br />

This has significant implications for dealing with al<br />

Qa'ida and suggests fundamentally rethinking post-9/11<br />

U.S. counterterrorism strategy: Policymakers need to understand<br />

where to prioritize their efforts with limited resources<br />

and attention.<br />

The authors report that religious terrorist groups take<br />

longer to eliminate than other groups and rarely achieve<br />

their objectives. The largest groups achieve their goals<br />

more <strong>of</strong>ten and last longer than the smallest ones do. Finally,<br />

groups from upper-income countries are more<br />

likely to be left-wing or nationalist and less likely to have<br />

religion as their motivation. The authors conclude that<br />

policing and intelligence, rather than <strong>military</strong> force,<br />

should form the backbone <strong>of</strong> U.S. efforts against al<br />

Qa'ida. And U.S. policymakers should end the use <strong>of</strong><br />

the phrase “war on terrorism” since there is no battlefield<br />

solution to defeating al Qa'ida.<br />

America needs to set its priorities and use its <strong>military</strong><br />

and law enforcement resources wisely or it will be ineffective<br />

in dealing with either international terrorism or<br />

domestic terrorism. "Terrorism" is defined as "The calculated<br />

use <strong>of</strong> violence or threat <strong>of</strong> violence to inculcate<br />

fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate governments or<br />

societies in the pursuit <strong>of</strong> goals that are generally political,<br />

religious, or ideological.” The actions <strong>of</strong> al Qa'ida<br />

have fit into that definition, but the Islamic world would<br />

argue that the actions <strong>of</strong> the U.S. in invading and occupying<br />

Iraq would also meet that definition. The point is that<br />

the U.S. policy makers have not displayed a keen understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> “terrorism.” Similarly, “domestic terrorism”<br />

must be recognized in order to effectively deal with it.<br />

"Domestic Terrorism" is defined as "Terrorism perpetrated<br />

by the citizens <strong>of</strong> one country against fellow countrymen.<br />

That includes acts against citizens <strong>of</strong> a second<br />

country when they are in the host country and not the<br />

principal or intended target.”<br />

The Pentagon in 1992 considered this problem as evidence<br />

by a memorandum circulated by the legal <strong>of</strong>ficer<br />

for the U.S. Army Military Police Operations Agency.

CONCLUSION<br />

Since 9/11, U.S. policy on national security has<br />

changed drastically in many ways. America invaded Iraq,<br />

and is still an occupation force. Counterinsurgency or<br />

antiterrorism <strong>military</strong> operations are being conducted in<br />

Afghanistan. The Homeland Security agency has been<br />

created to provide domestic security in the continental<br />

U.S. Local federal and state law enforcement agencies<br />

have the primary responsibility to deal with local criminal<br />

acts which can include acts <strong>of</strong> terrorism in the U.S., but<br />

after 9/11 combating terrorism has become a national priority.<br />

Military units, including activated National Guard<br />

units or personnel could be tasked to deal with terrorism<br />

in the U.S. if the President so orders. As the RAND research<br />

shows, policing and intelligence, rather than<br />

<strong>military</strong> force, should form the backbone <strong>of</strong> U.S. efforts<br />

against terrorism.<br />

If National Guard personnel were to act in a quasi law<br />

enforcement role to deal with terrorist acts or a broader<br />

terrorist threat in the U.S., hopefully they would be sufficiently<br />

trained to perform their duties consistent with<br />

Constitutional protections afforded the American populace.<br />

Many “pr<strong>of</strong>essional” police are caught on tape committing<br />

assaults.<br />

The <strong>military</strong> needs to be used judiciously and only<br />

when necessary to combat “terrorism” or it will become<br />

over-extended as it is now at a time when Russia is invading<br />

former members <strong>of</strong> the old USSR. Local police and<br />

intelligence agencies should be relied on to arrest or kill<br />

key members <strong>of</strong> terrorist groups. Lastly, U.S. policymakers<br />

should end the use <strong>of</strong> the phrase “war on terrorism”<br />

since there is no battlefield solution to defeating al<br />

Qa'ida.<br />

Courier page 13<br />

The above photographs are from the worldwide<br />

web. The upper two photograph show the Los<br />

Angeles riot and a California National Guardsman<br />

on patrol duty during the Los Angeles, California<br />

Riots. The photograph immediately above<br />

shows the Murrah Building in Okalahoma City,<br />

Okalahoma, after the bombing. All dramatically<br />

illustrate domestic terrorism in the United States.<br />

Proper training <strong>of</strong> National Guard members will prevent<br />

acts <strong>of</strong> uncontrolled violence. This Los Angeles Times photograph<br />

to the left depicts <strong>of</strong>ficers arresting an individual<br />

during the riots.

Courier page 14<br />

Documents Supporting the Editorial:<br />

“Lest We Forget”<br />

In honor <strong>of</strong> September 11, 2001, we remember<br />

those who lost their lives that day that changed forever<br />

the way Americans look at themselves and the<br />

world.<br />

We also take this time to honor the <strong>military</strong> men<br />

and women who have lost their lives in the service <strong>of</strong><br />

their country since that day, and for all the other wars<br />

and <strong>military</strong> actions before 9/11.<br />

We take this time to thank all <strong>military</strong> men and<br />

women who have served in the past, who serve now<br />

and who will serve in the future to keep our great<br />

country free.<br />

Freedom is not free.

From the Report <strong>of</strong> the Adjutant General <strong>of</strong> Arizona 1891,<br />

Edwin S. Gill, The Adjutant General<br />

Dated January 1, 1892<br />

To Hon. John N. Irwin,<br />

Governor and Commander-in-Chief:<br />

Sir:<br />

I have the honor to submit the annual report <strong>of</strong> the Adjutant<br />

General for the year ending December 31, 1891, as follows:<br />

(This report contained 26 pages.)<br />

The National Guard <strong>of</strong> Arizona now consists <strong>of</strong> one regiment<br />

<strong>of</strong> Infantry, composed <strong>of</strong> nine companies, organized<br />

into three battalions. The annual returns for the year show a<br />

present force <strong>of</strong> 288 <strong>of</strong>ficers and enlisted men. This report<br />

embraces only seven companies and the regimental and two<br />

battalion organizations. Companies A and C having failed to<br />

comply with orders issued, Colonel Brodie directed them to<br />

turn in their arms and equipment. Efforts are now making to<br />

re-organize both companies upon a firm basis, and I hope to<br />

be able to report success in a short time. The remaining companies<br />

are now recruiting and expect to soon have an enrollment<br />

<strong>of</strong> from 45 to 55 men each..<br />

Previous to March 19, 1891, Arizona had no Military<br />

Code, hence the present organization really dates subsequent<br />

to that time. Seven independent companies were organized<br />

during the summer and fall <strong>of</strong> 1890, but the lack <strong>of</strong> State aid<br />

caused the members to lose interest, and from December,<br />

1890, until April, 1891, hardly a drill was had. Another company<br />

known as “H” had been organized at Yuma, in January,<br />

1891, but pending the action <strong>of</strong> the Legislature nothing was<br />

done towards equipping it.<br />

The Code as adopted provides that “The organized militia<br />

shall consist <strong>of</strong> ten companies, *** <strong>of</strong> which the companies<br />

now formed shall form a part. *** Infantry companies may be<br />

organized into battalions <strong>of</strong> not less than two nor more than<br />

six companies, and such battalions into regiments <strong>of</strong> not less<br />

than two nor more than three battalions. To each regiment<br />

there shall be one Colonel, one Lieutenant-Colonel, three<br />

Majors, *** who shall be commissioned by the Commander-<br />

In-Chief. *** Each company duly organized under the provisions<br />

<strong>of</strong> this Code shall receive $30 per month to defray the<br />

expenses <strong>of</strong> maintaining each company, said amount payable<br />

monthly out <strong>of</strong> any funds in the Territorial Treasury not otherwise<br />

appropriated. The said monthly installment to be paid<br />

upon the requisition <strong>of</strong> the commanding <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> such company,<br />

the same being accompanied by vouchers approved by<br />

the Adjutant General.”<br />

General Orders, No. 1, the first ever issued to the National<br />

Guard <strong>of</strong> Arizona, were promulgated from this <strong>of</strong>fice, April<br />

23, directing the then existing companies to be mustered in<br />

under the new Code. This resulted in a virtual reorganization,<br />

the different companies completing their muster<br />

by May 30.<br />

[Further on in the report--]<br />

While the Code adopted was a start towards a <strong>military</strong><br />

organization, it is but just<br />

to the guard to say that the<br />

zeal <strong>of</strong> those in the organization<br />

has more to do with<br />

keeping it alive than aid<br />

derived from the Territory.<br />

Excepting the small sum <strong>of</strong><br />

$30 per month allowed<br />

each company, not one<br />

penny is appropriated for<br />

<strong>military</strong> expenses. No<br />

provisions whatever are<br />

made for the pay or transportation<br />

<strong>of</strong> troops if called<br />

Courier page 15<br />

Edwin S. Gill, The Adjutant General<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arizona, 1892.<br />

out, for encampments or inspections, for court-martials, for<br />

headquarters, regimental or battalion <strong>of</strong>fice expenses, nor for<br />

necessary <strong>of</strong>ficial transportation, nor in short for anything.<br />

The utter inconsistency <strong>of</strong> the law is especially shown in the<br />