Econ-244: Exercise Answers

Econ-244: Exercise Answers

Econ-244: Exercise Answers

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

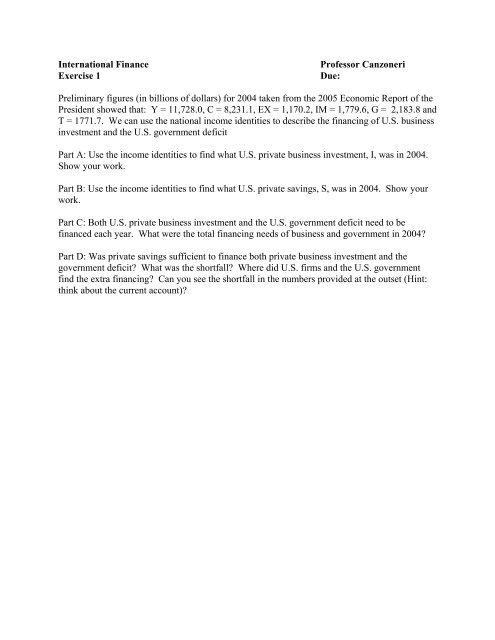

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 1 Due:<br />

Preliminary figures (in billions of dollars) for 2004 taken from the 2005 <strong>Econ</strong>omic Report of the<br />

President showed that: Y = 11,728.0, C = 8,231.1, EX = 1,170.2, IM = 1,779.6, G = 2,183.8 and<br />

T = 1771.7. We can use the national income identities to describe the financing of U.S. business<br />

investment and the U.S. government deficit<br />

Part A: Use the income identities to find what U.S. private business investment, I, was in 2004.<br />

Show your work.<br />

Part B: Use the income identities to find what U.S. private savings, S, was in 2004. Show your<br />

work.<br />

Part C: Both U.S. private business investment and the U.S. government deficit need to be<br />

financed each year. What were the total financing needs of business and government in 2004?<br />

Part D: Was private savings sufficient to finance both private business investment and the<br />

government deficit? What was the shortfall? Where did U.S. firms and the U.S. government<br />

find the extra financing? Can you see the shortfall in the numbers provided at the outset (Hint:<br />

think about the current account)?

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 1 ANSWERS<br />

Preliminary figures (in billions of dollars) for 2004 taken from the 2005 <strong>Econ</strong>omic Report of the<br />

President showed that: Y = 11,728.0, C = 8,231.1, EX = 1,170.2, IM = 1,779.6, G = 2,183.8 and<br />

T = 1771.7. We can use the national income identities to describe the financing of U.S. business<br />

investment and the U.S. government deficit<br />

Part A: Use the income identities to find what U.S. private business investment, I, was in 2004.<br />

Show your work.<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Y = C + I + G + EX - IM Y<br />

I = Y - (C + G + EX - IM) = 11,728.0 - (8,231.1 + 2,183.8 + 1,170.2 - 1,779.6) = 1,922.4<br />

Part B: Use the income identities to find what U.S. private savings, S, was in 2004. Show your<br />

work.<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Y = C + S + T Y S = Y - (C + T) = 11,728.0 - (8,231.1 + 1771.7) = 1725.2<br />

Part C: Both private U.S. business investment and the U.S. government deficit need to be<br />

financed each year. What were the total financing needs of business and government in 2004?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

I + (G - T) = 1,922.4 + ( 2,183.8 - 1771.7) = 2334.5<br />

Part D: Was private savings sufficient to finance both private business investment and the<br />

government deficit? What was the shortfall? Where did U.S. firms and the U.S. government<br />

find the extra financing? Can you see the shortfall in the numbers provided at the outset (Hint:<br />

think about the current account)?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Shortfall = [I + (G - T)] - S = 2334.5 - 1725.2 = 609.3<br />

They had to borrow from foreigners.<br />

As shown in class, the income identities imply that I + (G - T) = S - CA. So, the shortfall,<br />

[I + (G - T)] - S = - CA = IM - EX = 1,779.6 - 1,170.2 = 609.3. The current account deficit is<br />

U.S. borrowing from abroad.

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 2 Due:<br />

In the exercise, you will study two “arbitrage” conditions that show how financial markets<br />

determine exchange rates.<br />

I. CROSS RATE ARBITRAGE: E $/€ = E $/¥ * E ¥/€<br />

A. Find recent quotes (Financial Times or use the internet 1 ) for the dollar rates for Euro and<br />

Yen, and also find the cross rate between Euro and Yen. Suppose you sell $1 and buy<br />

Euros, then you sell the proceeds to buy Yen, and finally you sell the proceeds of that<br />

sale to buy back dollars. Do you end up with more or less than the $1 you started out<br />

with?<br />

B. <strong>Econ</strong>omists would expect the rate of return in Part A to be quite small. Explain why?<br />

(Hint: think what would happen if there were a big return?)<br />

1997 1998 1999 2000<br />

US Dollar 1 1 1 1<br />

JPN Yen 116.05 130.615 113.3 102.31<br />

INA Rupiah 2363 5535 8005 7050<br />

Figures for January 1 st of each year<br />

C. Use the above figures for Part C.<br />

1. Suppose you are manager of an Indonesian company that borrowed the equivalent<br />

of US$1,000,000 in Yen from a Japanese bank at the beginning of 1997. That<br />

amount is immediately converted into Rupiah for operations in your Indonesian<br />

factory. How much Rupiah do you now have for operations?<br />

2. If you were to pay back the Japanese bank at the beginning of 1998, how much<br />

Rupiah does you company have to pay for the full principal borrowed in 1997?<br />

What about in 1999? And in 2000?<br />

3. If you were manager of an Indonesian company that exported goods to America,<br />

how would these exchange rate movements have affected the dollar sales price of<br />

your goods?<br />

2. INTEREST RATE ARBITRAGE: R $ = R € + (E e<br />

$/€ - E $/€)/E $/€<br />

A. Suppose the rate of return on a Eurobond is 4.3%, and suppose the dollar is expected to<br />

depreciate by 0.5%; what is the expected dollar rate of return on the Eurobond?<br />

B. Suppose the rate of return on a Eurobond is 4.3%, and suppose the Euro is expected to<br />

appreciate by 0.5%; what is the expected dollar rate of return on the Eurobond?<br />

C. Use the interest rate parity equation to calculate the spot exchange rate (E $/€) when<br />

R $ = 0.045, R € = 0.043, and E e<br />

$/€ = 1.094. Is the resulting E $/€ greater or less than 1.094?<br />

D. Suppose R $, R €, and E e<br />

$/€ are at the values specified in Part C, but suppose that the spot<br />

exchange rate (E $/€) is initially equal to 1.094. Describe the market forces that would<br />

drive the spot rate to the answer you found in Part C.<br />

1 For example, you can use http://finance.yahoo.com or http://www.oanda.com/convert/classic

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 2 ANSWERS<br />

In the exercise, you will study two “arbitrage” conditions that show how financial markets<br />

determine exchange rates.<br />

I. CROSS RATE ARBITRAGE: E $/€ = E $/¥ * E ¥/€<br />

A. Find recent quotes (Financial Times or use the internet 2 ) for the dollar rates for Euro and<br />

Yen, and also find the cross rate between Euro and Yen. Suppose you sell $1 and buy<br />

Euros, then you sell the proceeds to buy Yen, and finally you sell the proceeds of that<br />

sale to buy back dollars. Do you end up with more or less than the $1 you started out<br />

with?<br />

ANSWER-<br />

On September 9, 2003: E $/€= 1.12, E ¥/$= 116.37, E ¥/€= 130.15<br />

$1@ E €/$ @ E ¥/€ @ E $/¥ = 1@ (1/1.12) @ 130.15 @ (1/116.37) = $0.9986 < $1<br />

B. <strong>Econ</strong>omists would expect the rate of return in Part A to be quite small. Explain why?<br />

(Hint: think what would happen if there were a big return?)<br />

ANSWER-<br />

If the loss were large, arbitragers would go the other way, making large profits. People<br />

would be buying (not selling) dollars. The dollar would appreciate, raising E €/$ and E ¥/$.<br />

This would make the return converge on 0.<br />

1997 1998 1999 2000<br />

US Dollar 1 1 1 1<br />

JPN Yen 116.05 130.615 113.3 102.31<br />

INA Rupiah 2363 5535 8005 7050<br />

Figures for January 1 st of each year<br />

C. Use the above figures for Part C.<br />

1. Suppose you are manager of an Indonesian company that borrowed the equivalent<br />

of US$1,000,000 in Yen from a Japanese bank at the beginning of 1997. That<br />

amount is immediately converted into Rupiah for operations in your Indonesian<br />

factory. How much Rupiah do you now have for operations?<br />

ANSWER-<br />

$1,000,000 @ E ¥/$ @ E R/¥ = $1,000,000 @ 116.05 @ (2363/116.05) = 2,363,000,000R in 1997<br />

2. If you were to pay back the Japanese bank at the beginning of 1998, how much<br />

Rupiah does you company have to pay for the full principal borrowed in 1997?<br />

What about in 1999? And in 2000?<br />

2 For example, you can use http://finance.yahoo.com or http://www.oanda.com/convert/classic

ANSWER-<br />

$1,000,000 @ E ¥/$ = $1,000,000 @ 116.05 = 116,050,000 Yen initially borrowed<br />

1998:<br />

116,050,000 Yen @ E R/¥ = 116,050,000 @ (5535/130.615) = 4,917,787,008 R<br />

1999:<br />

116,050,000 Yen @ (8005/113.3) = 8,199,296,117 R<br />

2000:<br />

116,050,000 Yen @ (7050/102.31) = 7,996,798,944 R<br />

3. If you were manager of an Indonesian company that exported goods to America,<br />

how would these exchange rate movements have affected the dollar sales price of<br />

your goods?<br />

ANSWER-<br />

From 1997 to 1999, the dollar is appreciating relative to the Rupiah, meaning the dollar<br />

sales price is decreasing (Indonesian goods are getting cheaper for Americans). In 2000,<br />

the Rupiah appreciated against the dollar from its 1999 level, making Indonesian goods<br />

more “expensive” in dollars than the year before- the dollar sales price went up.<br />

2. INTEREST RATE ARBITRAGE: R $ = R € + (E e<br />

$/€ - E $/€)/E $/€<br />

A. Suppose the rate of return on a Eurobond is 4.3%, and suppose the dollar is expected to<br />

depreciate by 0.5%; what is the expected dollar rate of return on the Eurobond?<br />

ANSWER-<br />

R € = 4.3%<br />

$ depreciation = (E e<br />

$/€ - E $/€)/E $/€ = .5%<br />

R $ = 4.3 + .5 = 4.8% dollar rate of return on the Eurobond<br />

B. Suppose the rate of return on a Eurobond is 4.3%, and suppose the Euro is expected to<br />

appreciate by 0.5%; what is the expected dollar rate of return on the Eurobond?<br />

ANSWER-<br />

R € = 4.3%<br />

Euro appreciation = $ depreciation = .5%<br />

R $ = 4.3 + .5 = 4.8% dollar rate of return on the Eurobond<br />

C. Use the interest rate parity equation to calculate the spot exchange rate (E $/€) when R $<br />

= 0.045, R € = 0.043, and Ee $/€ = 1.094. Is the resulting E $/€ greater or less than 1.094?<br />

ANSWER-<br />

Interest rate parity equation: R $ = R € + (Ee $/€ - E $/€)/E $/€<br />

.045 = .043 + (1.094 - E $/€)/E $/€<br />

.002 E $/€ = 1.094 - E $/€<br />

E $/€ = 1.092 ...the resulting E $/€ is less than 1.094<br />

D. Suppose R $, R €, and E e<br />

$/€ are at the values specified in Part C, but suppose that the spot<br />

exchange rate (E $/€) is initially equal to 1.094. Describe the market forces that would<br />

drive the spot rate to the answer you found in Part C.<br />

ANSWER-<br />

If the spot rate starts at 1.094, the left side of the interest rate parity eqn is greater than

the right, meaning there is a greater return on dollar bonds than Eurobonds. People would<br />

dump Euros and buy dollars, leading to an appreciation of the dollar relative to the Euro,<br />

and driving the spot rate back to that found in part C.

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 3 Due:<br />

The financial markets diagram shows how the money market and the bonds market<br />

simultaneously determine equilibrium E and R. In this exercise, you will get practice using it.<br />

I. Suppose the European Central Bank (ECB) raises its interest rate (R*) in an attempt to<br />

establish an anti-inflation reputation similar to the Bundesbank's.<br />

A. Use the financial markets diagram to show what this would do to the US interest rate (R) and<br />

exchange rate (E) assuming the FED did not change the US money supply. Explain intuitively<br />

why the exchange rate moves the direction it does? (Hint: what happens to the supplies and<br />

demands for home and foreign bonds?) What would all of this do to the price of US imports<br />

from Europe?<br />

B. Suppose the FED wanted to avoid these price level consequences in the US. Use the<br />

financial markets diagram to show what the FED would have to do to its money supply (M) to<br />

maintain the original exchange rate.<br />

C. Is there any way that the FED could simultaneously maintain its original exchange rate and<br />

its original interest rate? Justify your answer.<br />

II. As Europe comes out of its present recession, it will import more from the US, and this<br />

will expand US output (Y).<br />

A. Use the diagram to show what this will do to the US interest rate (R) and exchange rate (E).<br />

Explain intuitively why the interest rate and the exchange rate move in the directions they do.<br />

(Hint: again, what happens to supplies and demands?)<br />

B. Is there any way that the FED could change its money supply so as to simultaneously<br />

maintain its original exchange rate and its original interest rate? Use the diagram to justify<br />

your answer.

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 3 ANSWERS<br />

The financial markets diagram shows how the money market and the bonds market<br />

simultaneously determine equilibrium E and R. In this exercise, you will get practice using it.<br />

I. Suppose the European Central Bank (ECB) raises its interest rate (R*) in an attempt to<br />

establish an anti-inflation reputation similar to the Bundesbank's.<br />

A. Use the financial markets diagram to show what this would do to the US interest rate (R) and<br />

exchange rate (E) assuming the FED did not change the US money supply. Explain intuitively<br />

why the exchange rate moves the direction it does? (Hint: what happens to the supplies and<br />

demands for home and foreign bonds?) What would all of this do to the price of US imports<br />

from Europe?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

If the FED does not change M, then neither the<br />

supply nor the demand for M is affected,<br />

and R is unchanged.<br />

R*8 6 ED for Euro-bonds 6 people move<br />

out of $ and into Euro 6 $ depreciates.<br />

This depreciation raises the price of<br />

imports, since it now takes more $ to meet<br />

a given price quoted in Euro.<br />

B. Suppose the FED wanted to avoid these price level consequences in the US. Use the financial<br />

markets diagram to show what the FED would have to do to its money supply (M) to maintain the<br />

original exchange rate.<br />

ANSWER –<br />

The FED has to lower M enough to make R<br />

rise as much as R* did.<br />

Then, E remains at E1.

C. Is there any way that the FED could simultaneously maintain its original exchange rate and<br />

its original interest rate? Justify your answer.<br />

ANSWER –<br />

No. If the Fed changes M, then R must move to re-establish equilibrium in the money market. If<br />

the FED does not change M, then E must move, for reasons given in part A.<br />

II. As Europe comes out of its present recession, it will import more from the US, and this<br />

will expand US output (Y).<br />

A. Use the diagram to show what this will do to the US interest rate (R) and exchange rate (E).<br />

Explain intuitively why the interest rate and the exchange rate move in the directions they do.<br />

(Hint: again, what happens to supplies and demands?)<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Y8 6 L()8 6 money demand curve shifts down.<br />

ED for money 6 R8 to clear the money market.<br />

R8 6 ED for $-bonds 6 people try to get<br />

out of Euro and into $ assets 6 $ depreciates.<br />

B. Is there any way that the FED could change its money supply so as to simultaneously maintain<br />

its original exchange rate and its original interest rate? Use the diagram to justify your answer.<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Yes. FED has to increase money supply<br />

enough to accommodate the new money<br />

demand at the original R1.<br />

If R1 is maintained, then the E1 will also be<br />

maintained.<br />

This is possible here because the interest<br />

parity curve has not shifted.

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 4 Due:<br />

The AA-DD diagram illustrates the short run equilibrium in financial markets and in the goods<br />

market. In this exercise, you will get practice using it.<br />

I. Suppose the economy is initially at full employment, Y fe. Then, a stock market crash (such as<br />

the one we had in 1987 or 1998) makes firms curtail some of their investment projects (since they<br />

become harder to finance). Use the AA-DD diagram to show how this could cause a recession.<br />

Part A: Do the AA-DD curve analysis; be sure to explain why you shift any curve.<br />

Part B: Tell the “story” of what is happening in the goods market, and how it spills over to the<br />

financial markets.<br />

Part C: Show the path of adjustment to the new short run equilibrium. Is there any exchange rate<br />

“overshooting”?<br />

II. Now suppose the FED takes steps to offset the recession.<br />

Part A: Begin with an AA-DD diagram that shows where you ended up in question I; then show<br />

what the FED would have to do to restore the original level of output, Y fe. Once again, be sure<br />

to explain why you shift any curve.<br />

Part B: Tell the “story” of what is happening in the financial markets, and how it spills over to the<br />

goods market; show the path of adjustment to the new short run equilibrium. Is there any<br />

exchange rate “overshooting” in this case?<br />

Part C: Y has been restored to Y fe, but E has not been restored to its initial level, E 1. Why didn't it<br />

go back to its initial level; that is, why was a depreciation necessary?<br />

III. Suppose now that the FED wanted to simultaneously offset the recession and appreciate the<br />

exchange rate (for lower prices) to some E 3 < E 1; suppose further that it could persuade Congress<br />

to help in the effort.<br />

Part A: Begin with an AA-DD diagram that shows where you ended up in question I, and then<br />

show how a combined monetary and fiscal policy could restore both the initial level of output,<br />

Y fe, and the exchange rate E 3.<br />

Part B: Could either monetary or fiscal policy have achieved this alone?

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 4 ANSWERS<br />

The AA-DD diagram illustrates the short run equilibrium in financial markets and in the goods<br />

market. In this exercise, you will get practice using it.<br />

I. Suppose the economy is initially at full employment, Yfe. Then, a stock market crash (such as<br />

the one we had in 1987 or 1998) makes firms curtail some of their investment projects (since they<br />

become harder to finance). Use the AA-DD diagram to show how this could cause a recession.<br />

Part A: Do the AA-DD curve analysis; be sure to explain why you shift any curve.<br />

Part B: Tell the “story” of what is happening in the goods market, and how it spills over to the<br />

financial markets.<br />

Part C: Show the path of adjustment to the new short run equilibrium. Is there any exchange rate<br />

“overshooting”?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

The story: I9<br />

D(EP*/P,Y-T,I,G)9 6 DD shifts left<br />

initial effect is in goods mkt<br />

y d 9 6 y s follows<br />

spills over to financial markets<br />

Y9 6 L9 6 R9 6 E8.<br />

move out along AA; no impact effect,<br />

or E “overshooting”.

II. Now suppose the FED takes steps to offset the recession.<br />

Part A: Begin with an AA-DD diagram that shows where you ended up in question I; then show<br />

what the FED would have to do to restore the original level of output, Yfe. Once again, be sure<br />

to explain why you shift any curve.<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Fed has to buy bonds to increase money<br />

supply<br />

Part B: Tell the “story” of what is happening in the financial markets, and how it spills over to the<br />

goods market; show the path of adjustment to the new short run equilibrium. Is there any<br />

exchange rate “overshooting” in this case?<br />

ANSWER --<br />

FED has to M s8 The Story:<br />

initial effect in financial markets<br />

M s8 6 R9 6 E8<br />

E depreciates immediately to AA2<br />

spills over to goods market<br />

EP*/P8 6 yd 8 and y s follows<br />

as pictured, E initially “overshoots”.

Part C: Y has been restored to Yfe, but E has not been restored to its initial level, E1. Why didn't it<br />

go back to its initial level; that is, why was a depreciation necessary?<br />

ANSWER:<br />

E has to depreciate be cause (1) I9 6 E8 and (2) M s 8 6 E8; both work in the same direction on E,<br />

for reasons already given in the two “stories”.<br />

III. Suppose now that the FED wanted to simultaneously offset the recession and appreciate the<br />

exchange rate (for lower prices) to some E3 < E1; suppose further that it could persuade Congress<br />

to help in the effort.<br />

Part A: Begin with an AA-DD diagram that shows where you ended up in question I, and then<br />

show how a combined monetary and fiscal policy could restore both the initial level of output,<br />

Yfe, and the exchange rate E3. Part B: Could either monetary or fiscal policy have achieved this alone?<br />

ANSWER --<br />

Fiscal policy should T9 and/or G8 to<br />

make DD cut the Y fe line at E 3.<br />

Monetary policy should M s 9 to make AA<br />

cut the Y fe line at E 3.<br />

Neither policy could do this alone; have<br />

to move both curves to get (E 3,Y fe).<br />

Have to combine an expansionary<br />

fiscal policy with a contractionary<br />

monetary policy.

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 5 Due:<br />

In this exercise, you will study the relationship between the substitutability of (home and<br />

foreign) bonds and central bank independence.<br />

Suppose the FED wants to raise R (for domestic reasons) and depreciate E (for external<br />

reasons); that is, the FED wants to achieve the point (E 2,R 2) in the diagram below.<br />

I. Suppose B and B* are imperfect substitutes. Show that an OMO can bring R to R 2, and that a<br />

sterilized intervention can then bring E to E 2. In each case, explain what assets the FED swaps<br />

with the private sector.<br />

II. Suppose B and B* are perfect substitutes. Is there any way the FED can achieve the point<br />

(E 2,R 2)? What choices of (E,R) is the FED limited to?<br />

III. In the US, the Treasury Department (and not the FED) has the right to set exchange rate<br />

policy. If this right is interpreted to mean that Treasury can tell the FED what E to set, then does<br />

this right in effect abrogate the independence of the central bank? That is, can the FED still set<br />

whatever R it wants, independent of the wishes of the Treasury?

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 5 ANSWERS –<br />

Suppose the FED wants to raise R (for domestic reasons) and depreciate E (for external<br />

reasons); that is, the FED wants to achieve the point (E 2,R 2) in the diagram below.<br />

I. Suppose B and B* are imperfect substitutes. Show that an OMO can bring R to R 2, and that a<br />

sterilized intervention can then bring E to E 2. In each case, explain what assets the FED swaps<br />

with the private sector.<br />

ANSWER --<br />

1. Contractionary OMO: FED sells B (in exchange for M) to bring M s to M 2 shown above.<br />

Note: The OMO will raise B/B*, increase ρ(B/B*) and shift interest parity condition up.<br />

far enough to achieve (E 2,R 2), then a sterilized intervention<br />

is needed to shift it further.<br />

If the curve has not shifted<br />

If the curve has already shifted too far up, then a sterilized intervention has to shift it<br />

back down some.<br />

In what follows, I will assume that the OMO has not shifted it far enough.<br />

2. Sterilized Intervention:<br />

FEI: FED buys B* (raising B/B*) in exchange for M.<br />

Offsetting OMO: FED sells B (raising B/B* even more) in exchange for M.<br />

Net effect: no change in M (that is, it stays at M 2), but B/B*, and ρ(B/B*), rise enough to<br />

achieve (E 2,R 2).

II. Suppose B and B* are perfect substitutes. Is there any way the FED can achieve the point<br />

(E 2,R 2)? What choices of (E,R) is the FED limited to?<br />

ANSWER --<br />

No. If bonds are perfect substitutes, FED's operations can not shift interest parity curve. In<br />

effect, it is limited to shifting the equilibrium along this curve.<br />

III. In the US, the Treasury Department (and not the FED) has the right to set exchange rate<br />

policy. If this right is interpreted to mean that Treasury can tell the FED what E to set, then does<br />

this right in effect abrogate the independence of the central bank? That is, can the FED still set<br />

whatever R it wants, independent of the wishes of the Treasury?<br />

ANSWER --<br />

The answer depends on whether or not bonds are imperfect substitutes.<br />

If bonds are imperfect substitutes, then the FED retains independence over interest rate policy.<br />

The FED can use OMO's to achieve its own R-target, and then use sterilized interventions to<br />

achieve the Treasury's E-target.<br />

If bonds are imperfect substitutes, then the FED does lose its independence; the Treasury's E<br />

target determines the R that the FED must set.

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 6 Due:<br />

In this exercise, you will practice finding Nash solutions, and we will develop further Barro &<br />

Gordon's Inflation Credibility Model and Obstfeld's 2 nd Generation Speculative Attacks Model.<br />

I. Finding Nash Solutions –<br />

Part A: Define a “Nash Solution” to a non-cooperative game. (Hint: What must each player<br />

be doing in the Nash solution.)<br />

Part B: Consider the two games below. Start with Game 1, where the Nash solutions have<br />

already been circled. Go from box to box explaining why each is, or is not, a Nash<br />

solution. Then, do the same for Game 2, and circle the Nash solution(s?).<br />

II. Recall Able and Bernanke's box matrix example of Barro-Gordon's Inflation Credibility Model:<br />

Part A: Suppose the CB just announced that it would play M l, and that there was no need for the<br />

wage setters to expect P h. Would this announcement be believed? Why or why not?<br />

Part B: Suppose we change the point assignments as follows:<br />

W Setters CB<br />

N* 1 0 Now, the CB is not as concerned about achieving high levels of N:<br />

N h 0 1 N h gets 1 point instead of 2, N l gets -1 instead of -2.<br />

N l 0 -1 Otherwise, the point assignments are the same.<br />

P h 0 0 Recalculate the CB's payoffs in the four boxes, and find the<br />

P l 0 1 new Nash solution(s?). (Hint: there may be more than one.)<br />

Part C: If there are multiple solutions, how might the CB bring about the best one?

III. Recall Obstfeld's box matrix example of a “2 nd Generation” Speculative Attack Model:<br />

Part A: When foreign reserves were FR = 20, “fundamentals” were so strong that an attack<br />

was impossible. In this model, what is the minimum number of reserves that would be<br />

required to rule out the possibility of multiple equilibria, and thus, self-fulfilling attacks?<br />

Part B: When foreign reserves were FR = 6, “fundamentals” were so weak that an attack was<br />

inevitable. What is the minimum number of reserves that would at least keep the attack from<br />

being inevitable?<br />

Part C: Who do you think is to blame for exchange rate crises in Obstfeld's model ? The<br />

government? Speculators?

International Finance Professor Canzoneri<br />

<strong>Exercise</strong> 6 Due: ANSWERS<br />

In this exercise, you will practice finding Nash solutions, and we will develop further Barro &<br />

Gordon's Inflation Credibility Model and Obstfeld's 2 nd Generation Speculative Attacks Model.<br />

I. Finding Nash Solutions –<br />

Part A: Define a “Nash Solution” to a non-cooperative game. (Hint: What must each player<br />

ANSWER --<br />

be doing in the solution.)<br />

We have a Nash Solution when each player is doing the best he/she can do, given the actions<br />

of the other players in the game.<br />

Part B: Consider the two games below. Start with Game 1, where the Nash solutions have<br />

already been circled. Go from box to box explaining why each is, or is not, a Nash<br />

solution. Then, do the same for Game 2, and circle the Nash solution(s?).<br />

ANSWER --

ANSWER –<br />

Game 1: Game 2:<br />

NW box: both would deviate. NW box: neither would deviate.<br />

SW box: neither would deviate. SW box: Row would deviate.<br />

SE box: both would deviate. SE box: both would deviate.<br />

NE box: neither would deviate. NE box: Column would deviate.<br />

II. Recall Able and Bernanke's box matrix example of Barro-Gordon's Inflation Credibility Model:<br />

Part A: Suppose the CB just announced that it would play M l, and that there was no need for the<br />

wage setters to expect P h. Would this announcement be believed? Why or why not?<br />

ANSWER --<br />

It would not be believed. Wage setters know that if they play W l (ie the SE box), the CB will<br />

be tempted to play M h, resulting in the NE box. The announcement is not credible.<br />

Part B: Suppose we change the point assignments as follows:<br />

W Setters CB<br />

N* 1 0 Now, the CB is not as concerned about achieving high levels of N:<br />

N h 0 1 N h gets 1 point instead of 2, N l gets -1 instead of -2.<br />

N l 0 -1 Otherwise, the point assignments are the same.<br />

P h 0 0 Recalculate the CB's payoffs in the four boxes, and find the<br />

P l 0 1 new Nash solution(s?). (Hint: there may be more than one.)

ANSWER – Here, there are two Nash solutions.<br />

Since the CB's incentive to create a surprise<br />

inflation is not as strong not, the good<br />

equilibrium (the SE box) is a possible<br />

outcome.<br />

Part C: If there are multiple solutions, how might the CB bring about the best one?<br />

ANSWER --<br />

Here, the CB could simply announce that it would play M l. There is no reason for the wage<br />

setters not to believe the announcement. There is no credibility problem, since SE is a Nash<br />

solution.<br />

III. Recall Obstfeld's box matrix example of a “2 nd Generation” Speculative Attack Model:<br />

Part A: When foreign reserves were FR = 20, “fundamentals” were so strong that an attack was<br />

impossible. In this model, what is the minimum number of reserves that would be required to<br />

rule out the possibility of multiple equilibria, and thus, self-fulfilling attacks?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

The combined holdings of the two traders is 6 + 6 = 12. If the central bank holds 13, then even<br />

if both traders attack, they can not deplete the reserves and force a devaluation. So, 13 is the<br />

minimum level of reserves required to rule out any possibility of an attack.

Part B: When foreign reserves were FR = 6, “fundamentals” were so weak that an attack was<br />

inevitable. What is the minimum number of reserves that would at least keep the attack from<br />

being inevitable?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

Each trader holds 6. If the central bank holds 7, then no one trader alone can deplete the<br />

reserves. So, 7 is the minimum level of reserves required to keep the attack from being<br />

inevitable.<br />

Part C: Who do you think is to blame for exchange rate crises in Obstfeld's model ? The<br />

government? Speculators?<br />

ANSWER –<br />

There is no one answer to this. Governments can make themselves invulnerable to attack by<br />

keeping fundamentals very strong. On the other hand, this may (or may not) be a costly thing<br />

to do. Governments have to at least keep fundamentals in the intermediate range, so that an<br />

attack is not inevitable. And if fundamentals are in that intermediate range, there is no good<br />

reason for an attack, other than the greed of speculators.