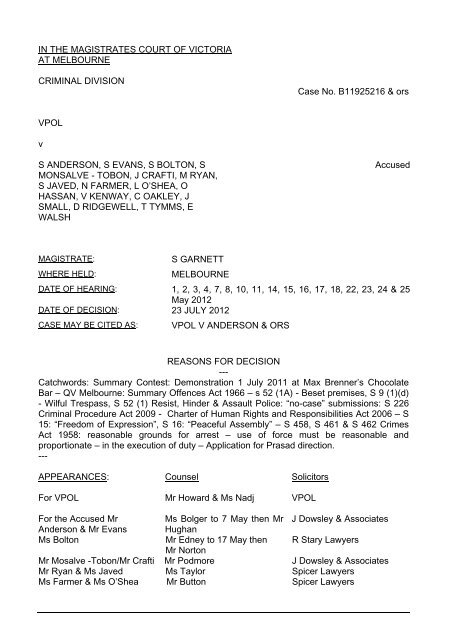

Vpol v Anderson & Ors - Magistrates' Court of Victoria

Vpol v Anderson & Ors - Magistrates' Court of Victoria

Vpol v Anderson & Ors - Magistrates' Court of Victoria

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

IN THE MAGISTRATES COURT OF VICTORIA<br />

AT MELBOURNE<br />

CRIMINAL DIVISION<br />

VPOL<br />

v<br />

S ANDERSON, S EVANS, S BOLTON, S<br />

MONSALVE - TOBON, J CRAFTI, M RYAN,<br />

S JAVED, N FARMER, L O’SHEA, O<br />

HASSAN, V KENWAY, C OAKLEY, J<br />

SMALL, D RIDGEWELL, T TYMMS, E<br />

WALSH<br />

MAGISTRATE: S GARNETT<br />

WHERE HELD: MELBOURNE<br />

Case No. B11925216 & ors<br />

Accused<br />

DATE OF HEARING: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 23, 24 & 25<br />

May 2012<br />

DATE OF DECISION: 23 JULY 2012<br />

CASE MAY BE CITED AS: VPOL V ANDERSON & ORS<br />

REASONS FOR DECISION<br />

---<br />

Catchwords: Summary Contest: Demonstration 1 July 2011 at Max Brenner’s Chocolate<br />

Bar – QV Melbourne: Summary Offences Act 1966 – s 52 (1A) - Beset premises, S 9 (1)(d)<br />

- Wilful Trespass, S 52 (1) Resist, Hinder & Assault Police: “no-case” submissions: S 226<br />

Criminal Procedure Act 2009 - Charter <strong>of</strong> Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 – S<br />

15: “Freedom <strong>of</strong> Expression”, S 16: “Peaceful Assembly” – S 458, S 461 & S 462 Crimes<br />

Act 1958: reasonable grounds for arrest – use <strong>of</strong> force must be reasonable and<br />

proportionate – in the execution <strong>of</strong> duty – Application for Prasad direction.<br />

---<br />

APPEARANCES:<br />

Counsel Solicitors<br />

For VPOL Mr Howard & Ms Nadj VPOL<br />

For the Accused Mr<br />

Ms Bolger to 7 May then Mr J Dowsley & Associates<br />

<strong>Anderson</strong> & Mr Evans Hughan<br />

Ms Bolton Mr Edney to 17 May then<br />

Mr Norton<br />

R Stary Lawyers<br />

Mr Mosalve -Tobon/Mr Crafti Mr Podmore J Dowsley & Associates<br />

Mr Ryan & Ms Javed Ms Taylor Spicer Lawyers<br />

Ms Farmer & Ms O’Shea Mr Button Spicer Lawyers<br />

!Undefined Bookmark, I

Mr Hassan Mr Bayles R Stary Lawyers<br />

Ms Kenway Ms O’Brien R Stary Lawyers<br />

Mr Oakley & Mr Small Ms Caruso J Dowsley & Associates<br />

Mr Ridgewell Ms L Murphy J Dowsley & Associates<br />

Mr Tymms Ms P Murphy R Stary Lawyers<br />

Ms Walsh Mr Wilson R Stary Lawyers<br />

!Undefined Bookmark, II

HIS HONOUR:<br />

1 The 16 co-accused are charged with <strong>of</strong>fences against the Summary Offences<br />

Act (1966) arising out <strong>of</strong> their involvement in a demonstration at Max<br />

Brenner’s Chocolate Bar at QV Melbourne on 1 July 2011. All <strong>of</strong> the accused<br />

are alleged to have ‘wilfully and without lawful authority beset premises’<br />

contrary to S 52(1A) and ‘wilful trespass’ contrary to S 9 (1)(d) <strong>of</strong> the Act. In<br />

addition, 8 <strong>of</strong> the accused face charges <strong>of</strong> assaulting, resisting or hindering<br />

police in the execution <strong>of</strong> their duties contrary to S 52(1). (The charge <strong>of</strong><br />

resisting arrest laid against Mr Crafti was withdrawn by the prosecution on the<br />

final day <strong>of</strong> hearing).<br />

2 The matter proceeded as a summary contest over a period <strong>of</strong> 17 days with<br />

evidence being given by 26 police witnesses and 4 civilian witnesses. At the<br />

conclusion <strong>of</strong> the prosecution case, all <strong>of</strong> the accused made “no-case”<br />

submissions in respect to all <strong>of</strong> the charges in accordance with S 226 <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Criminal Procedure Act 2009. The parties provided the court with<br />

comprehensive written and oral submissions in support <strong>of</strong> their respective<br />

positions.<br />

3 The evidence revealed that two previous demonstrations occurred at Max<br />

Brenner’s Chocolate Bar at QV on 1 April 2011 and 20 May 2011. The<br />

protests were apparently organised and attended by members <strong>of</strong> a coalition<br />

against Israeli Apartheid as part <strong>of</strong> a campaign <strong>of</strong> Boycotts, Divestments and<br />

Sanctions (BDS) which also included members <strong>of</strong> a Socialist Alliance Group.<br />

The court heard evidence that on 1 July there were approximately 150-200<br />

protestors gathered in QV Square in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s taking part in the<br />

demonstration and 132 police members on duty including general duty<br />

members, members <strong>of</strong> the Public Order Response Team (PORT) and<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the Public Order Management Team (POMT).<br />

4 As indicated, the court heard evidence from 26 police <strong>of</strong>ficers who were<br />

present on the night which included Inspector Beattie, the Field Commander<br />

1 DECISION

managing the police operation and Senior Sergeant Falconer, the Operations<br />

Commander <strong>of</strong> the Public Order Management Team who were the police<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers tasked to form arrest teams. Senior Sergeant Falconer gave evidence<br />

over 3 days (approximately 9 hours) and was subject to intense cross-<br />

examination in relation to the discussions that occurred between police and<br />

QV management prior to the demonstration on 1 July, the operational tactics<br />

and the arrests that occurred. Evidence was also given by the Operations<br />

Manager <strong>of</strong> QV, Mr Appleford, Ms Fleming, General Manager <strong>of</strong> QV, Mr<br />

Kandasamy, Technical Manager at QV who operated and monitored the<br />

CCTV at the complex and Mr Shrestha, the State Manager <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s.<br />

Importantly, in the context <strong>of</strong> this case, over 4 hours <strong>of</strong> QV CCTV and police<br />

video footage taken by Senior Constables McLaughlin, Campbell and Oakley<br />

was tendered and shown to a number <strong>of</strong> witnesses during their cross-<br />

examination.<br />

5 In order to understand the events that occurred on 1 July and the foundation<br />

for the charges that have been laid against each <strong>of</strong> the accused it is<br />

necessary to go into some detail <strong>of</strong> the evidence given in relation to events<br />

preceding the demonstration on 1 July. Mr Appleford, Ms Fleming, Senior Sgt<br />

Falconer and Inspector Beattie gave evidence that a number <strong>of</strong> meetings<br />

occurred between them, Melbourne Central Management and other police in<br />

the period between 20 May and 1 July as they were aware through social<br />

media sites that a further demonstration would occur on 1 July. In addition, the<br />

<strong>Victoria</strong> Police obtained legal advice from the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Government Solicitors<br />

Office as to what powers they had in relation to the protestors should certain<br />

events occur and QV management also obtained legal advice as to their rights<br />

to request the protestors to leave the site and what, if any, legal remedies<br />

were open to the owners/occupiers.<br />

6 Mr Appleford and Ms Fleming gave evidence that the QV site is private<br />

property which is owned by Commonwealth Management Investments Ltd<br />

2 DECISION

and <strong>Victoria</strong> Square QV Investments. The Title Search <strong>of</strong> the property in<br />

question dated 10 May 2012 was tendered which indicates the registered<br />

proprietor is Commonwealth Managed Investments Ltd. Mr Appleford and Ms<br />

Fleming told the court that the property, although privately owned, is subject to<br />

an agreement (which is registered on the Title) with the Melbourne City<br />

Council in accordance with S 173 <strong>of</strong> the Planning and Environment Act 1987.<br />

The agreement contains a covenant which requires QV to keep the laneways<br />

and QV Square open to the public 24 hours a day and 7 days a week with<br />

some exceptions.<br />

7 Mr Appleford and Ms Fleming gave evidence that in preparation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

demonstration occurring and as a result <strong>of</strong> their discussions with Melbourne<br />

Central Management and the police they implemented a risk management<br />

plan which included; retailers at QV were spoken to and given letters warning<br />

them that the protest was to occur; QV Management was working closely with<br />

<strong>Victoria</strong> Police on management plans which included police presence being<br />

high and QV security to be present to protect the precinct and minimise any<br />

disruption; Conditions <strong>of</strong> Entry signs were placed at entry points, within the<br />

property and on pillars outside Max Brenner’s; the loading dock was closed to<br />

allow the police to establish a base for their operational duties (including<br />

where to take and “process” protestors who were arrested); additional security<br />

was employed by QV for the night; the removal <strong>of</strong> tables, chairs and the<br />

Perspex barrier at the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s; the closure <strong>of</strong> the “Light and<br />

Sound” Exhibition Marquee in QV Square at 6 p.m.; and, written authorisation<br />

was given by the owners <strong>of</strong> the site to Inspector Beattie, at his request, to use<br />

police powers to remove persons from the site where their entitlement to enter<br />

and remain had been revoked by QV management.<br />

8 Inspector Beattie gave evidence that he obtained legal advice from the<br />

<strong>Victoria</strong>n Government Solicitors Office regarding; the wording on a Notice<br />

which was distributed to protestors by Sgt Nash in front <strong>of</strong> the State Library<br />

3 DECISION

prior to the protestors making their way to QV Square; the wording on signage<br />

to be placed at QV; and, the announcement made by Mr Appleford to the<br />

protestors at approximately 6.50 p.m. purporting to revoke their licence to be<br />

on the property. The Notice distributed at the State Library stated:<br />

29 June 2011<br />

Boycott Apartheid Israel Rally<br />

1 st July, 2011<br />

<strong>Victoria</strong> Police wishes to advise you <strong>of</strong> the following:-<br />

Your demonstration activity will be closely monitored by police;<br />

Police will act to prevent violence, and will take all reasonable steps to arrest anyone<br />

<strong>of</strong>fending in this regard;<br />

The interiors <strong>of</strong> Melbourne Central and Q.V. are private property.<br />

If you propose to demonstrate disapproval <strong>of</strong> the political or social<br />

Interests <strong>of</strong> any retail tenant within Melbourne Central or QV, or<br />

create any form <strong>of</strong> disturbance in and around retail premises<br />

within Melbourne Central or QV, then you are prohibited from<br />

entering those shopping complexes;<br />

Please carefully note signage at entry points to Melbourne Central<br />

and QV complexes regarding behavioural conditions required<br />

within those places. Any person who defies this advice may be<br />

liable for breaching trespass laws;<br />

Police may also act to prevent demonstrators besetting private<br />

businesses (Offence – Beset Premises S.52 (1A) Summary<br />

Offences Act 1966);<br />

During the rally Police will attempt to communicate to<br />

Demonstrators any proposed escalation in Police tactics. Police<br />

will generally adopt a pro – prosecution policy for <strong>of</strong>fences<br />

against the person or against property.<br />

Inspector M.Beattie (Operations Officer)<br />

4 DECISION

9. The wording on the signage placed in and around QV by Jamie Rundell,<br />

Security Officer, at QV at the direction <strong>of</strong> Mr Appleford and on the advice <strong>of</strong><br />

Inspector Beattie was:<br />

Sign 1: ‘CONDITIONS OF ENTRY<br />

All persons, acting individually or forming part <strong>of</strong> an assembly <strong>of</strong> people, who propose to<br />

intentionally obstruct, hinder or impede any member <strong>of</strong> the public from entering any retail<br />

premises in Melbourne QV, or who propose to demonstrate disapproval <strong>of</strong> the political or<br />

social interests <strong>of</strong> a retail tenant, or create any form <strong>of</strong> disturbance in and around retail<br />

premises in QV, are prohibited from entering QV.<br />

QV Melbourne’<br />

Sign 2: ‘CONDITIONS OF ENTRY<br />

Any person, acting individually or forming part <strong>of</strong> an assembly <strong>of</strong> people, who are engaged in<br />

behaviour that obstructs, hinders or impedes any member <strong>of</strong> the public from entering any<br />

retail premise in QV, or who demonstrates disapproval <strong>of</strong> the political or social interests <strong>of</strong> a<br />

retail tenant, or who create any form <strong>of</strong> disturbance in and around retail premises within QV,<br />

will be ejected immediately from QV and consent to re-enter will be at the discretion <strong>of</strong> Centre<br />

Management.<br />

QV Melbourne’<br />

10. The announcement read by Mr Appleford at approximately 6.43 p.m. whilst<br />

using a megaphone at the request <strong>of</strong> Inspector Beattie was:<br />

“My name is Mark Appleford and I am the operations Manager at QV Shopping Centre.<br />

Where you are presently located is private property. I am authorised in writing to act on behalf<br />

<strong>of</strong> the owners <strong>of</strong> this private property being QV Melbourne Shopping Centre. You are<br />

demonstrating disapproval <strong>of</strong> the political or social interests <strong>of</strong> a retail tenant <strong>of</strong> this shopping<br />

centre. Accordingly you are breaching an express condition <strong>of</strong> entry to this property not to<br />

perform this type <strong>of</strong> protest activity. You have no lawful right to remain. I require you all to<br />

leave this private property immediately. Thank you.”<br />

11. Inspector Beattie also confirmed that at his request he received a letter from<br />

Ms Fleming dated 1 July requesting and authorising <strong>Victoria</strong> Police to use its<br />

powers during the demonstration if the police considered it appropriate. Ms<br />

Fleming told the court that the letter was provided with QV’s legal team<br />

involved in its drafting. The letter stated;<br />

“The retail, commercial and common areas <strong>of</strong> QV Melbourne (the site) are managed by<br />

Colonial First State Property Management Pty Ltd (trading as Colonial First State Global<br />

Asset Management, CFSGAM), as duly appointed agent <strong>of</strong> the owners <strong>of</strong> the site, <strong>Victoria</strong><br />

Square QV Investments Pty Ltd and Commonwealth Managed Investments Ltd pursuant to a<br />

Property Management Agreement dated 30 November 2010 (PMA).<br />

All parts <strong>of</strong> the Site are private property and the owners have the right to revoke an<br />

5 DECISION

individual’s entitlement to enter the Site and to request Police Officers to assist in removing<br />

persons from the Site should they not leave when asked. Under the PMA, the CFSGAM<br />

Centre Management team have effective control <strong>of</strong> the running <strong>of</strong> the Site (including QV<br />

Square and the laneways) and perform that function as agent for the owners.<br />

With regard to Protestors at QV Melbourne, we request the <strong>Victoria</strong> Police use its powers to<br />

remove them from the precinct where police consider this appropriate. We intend to revoke<br />

the entitlement to enter the Site <strong>of</strong> any individuals who cause disruption to the lawful operation<br />

<strong>of</strong> business within the Site and who refuse to leave the precinct when required by Centre<br />

Management.”<br />

12. Ms Fleming gave evidence that following the 20 May 2011 demonstration, she<br />

had informed <strong>Victoria</strong> Police at their meetings that QV Management and the<br />

owners wanted the site to be safe and did not want the retailers disrupted.<br />

She told the court that QV management deferred to <strong>Victoria</strong> Police in relation<br />

to the planning and “who, how and when to arrest”. She told the court that she<br />

was aware <strong>of</strong> the plan for Mr Appleford to make his announcement and when<br />

it was to occur as this issue was discussed in meetings with Melbourne<br />

Central management and the police because QV management were<br />

concerned about the times and duration <strong>of</strong> the demonstrations which were<br />

occurring on Friday evenings between 6-6.30 p.m. Ms Fleming was adamant<br />

that a time limit for the demonstration was not set in the meetings nor were<br />

possible criminal charges discussed, if arrests were to be made. She was also<br />

adamant (although later expressed reservations as to her recollection) that<br />

QV did not seek and obtain legal advice as to possible civil action they could<br />

take prior to 1 July. In relation to the S 173 agreement she described QV as;<br />

“an unusual place because it is a public place that is privately owned”. She<br />

noted that QV Square and the laneways are “public access space” and she<br />

had not thought it relevant to inform <strong>Victoria</strong> Police <strong>of</strong> the S 173 agreement<br />

prior to 1 July.<br />

13. Inspector Beattie gave evidence that there were a number <strong>of</strong> planning<br />

meetings in anticipation <strong>of</strong> the 1 July demonstration with QV management and<br />

Melbourne Central management. He recalled that at a meeting on 16 June the<br />

participants did discuss civil options that were available to the owners<br />

including “banning notices” and injunctions but it was left to them to obtain<br />

their own legal advice on that issue and they subsequently informed him that<br />

they would not pursue that avenue. He also told the court that on the night it<br />

6 DECISION

was left to QV Management as to if, and when, to request the protestors to<br />

leave. He confirmed that prior to 1 July, he had requested documentation from<br />

QV in order to satisfy himself that QV Management had the right to withdraw<br />

an individual’s right to be on the premises. Inspector Beattie agreed in cross<br />

examination that a 20 minute time frame for the demonstration was discussed<br />

in those meetings but it was not pre-determined.<br />

14 Senior Sergeant Falconer gave evidence that he took part in the planning<br />

meetings with Melbourne Central management and QV management after the<br />

demonstration on 20 May. He told the court that the police attended QV on 1<br />

July at the request <strong>of</strong> QV management to prevent a breach <strong>of</strong> the peace and<br />

potential damage to property. He also confirmed that it was planned that if<br />

arrests were to be made those identified as leaders <strong>of</strong> the demonstration<br />

would be targeted. He told the court that QV management informed him at a<br />

meeting on 2 June that they were “happy” for the demonstration to occur<br />

providing there was no interruption to the operation <strong>of</strong> businesses and<br />

providing the demonstration did not last too long. He told the court that Mr<br />

Allen, from Melbourne Central management suggested a time frame <strong>of</strong> 20<br />

minutes but that it was up to QV management on the night as to how long<br />

they were prepared to allow the demonstration to occur. He confirmed the<br />

evidence given by Inspector Beattie that the option <strong>of</strong> the shopping centres<br />

taking civil action was discussed at the meetings conducted prior to 1 July and<br />

that he had advised them that the police could only intervene if the protestors<br />

committed criminal <strong>of</strong>fences. He confirmed that <strong>Victoria</strong> Police obtained legal<br />

advice from the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Government Solicitors Office regarding the law <strong>of</strong><br />

trespass and beset and that he also researched the law and explored the<br />

police powers <strong>of</strong> arrest should those laws be breached. He gave evidence that<br />

at the meeting with the shopping centres on 29 June they informed him they<br />

had decided not to pursue civil action. He also told the court that he had no<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> the existence <strong>of</strong> the S 173 agreement between QV and the<br />

Melbourne City Council.<br />

The Demonstration<br />

15. The evidence indicates that prior to making their way to QV Square on Level<br />

2, many <strong>of</strong> the protestors gathered at the front <strong>of</strong> the State Library on<br />

Swanston St where a number <strong>of</strong> speeches were made. Sgt Nash gave<br />

7 DECISION

evidence that he distributed Notices to the protestors, as referred to above,<br />

including Ms Kenway, Mr Oakley and Mr Hassan. The protestors then went to<br />

Melbourne Central before attending QV at approximately 6.29 p.m. It appears<br />

from the police video footage that many <strong>of</strong> the protestors entered QV Square<br />

via the stairs and escalators on Level 1. Once in QV Square, the protestors<br />

formed solid lines, 3-4 deep in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s whilst the others “milled”<br />

in the Square between Max Brenner’s and the Marquee situated in the middle<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Square. On viewing the CCTV and the video recordings from Senior<br />

Constables McLaughlin, Campbell and Oakley, the following general<br />

observations can be made;<br />

when the protestors arrived at QV Square, there were customers both<br />

inside and outside Max Brenner’s on Red Cape Lane at the tables and<br />

chairs provided and there were approximately 15 police at the corner <strong>of</strong><br />

Max Brenner’s and Red Cape Lane;<br />

Members <strong>of</strong> the public are seen to move up and down Red Cape Lane<br />

passing between the police situated near Max Brenner’s and further<br />

down Red Cape Lane;<br />

At 6.28 p.m. a police line is formed across Red Cape Lane between<br />

Max Brenner’s and the “Grill’d” restaurant;<br />

Police members on that line prevent members <strong>of</strong> the public from<br />

proceeding down Red Cape Lane towards Swanston St;<br />

a solid police line is established across the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s<br />

inside the line <strong>of</strong> pillars facing the Square;<br />

protestors form solid lines (4 deep) in front <strong>of</strong> the police line outside<br />

Max Brenner’s facing the Square;<br />

by 6.32 p.m. a solid police line is observed at the bottom <strong>of</strong> Red Cape<br />

Lane near Swanston St;<br />

a loose line <strong>of</strong> police extends from the corner <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s across<br />

Red Cape Lane;<br />

a security guard is observed at the Red Cape Lane entrance to Max<br />

8 DECISION

Brenner’s;<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> customers are seen entering and leaving Max Brenner’s;<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> protestors gather in front <strong>of</strong> the police line across Red<br />

Cape Lane;<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> protestors are making speeches and chanting aided by the<br />

use <strong>of</strong> megaphones;<br />

Mr <strong>Anderson</strong> approaches the police line on Red Cape Lane;<br />

the police line and protestor lines immediately in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s<br />

appear to engage in pushing forward and backwards;<br />

a member <strong>of</strong> the public engages in argument with some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

protestors in the middle <strong>of</strong> QV Square;<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the public are seen moving through protestors in the<br />

middle <strong>of</strong> QV Square;<br />

POMT members move behind the police line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s;<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the public who approach the police line across Red Cape<br />

Lane are directed to proceed to the north east side <strong>of</strong> QV Square and<br />

not down Red Cape Lane;<br />

Inspector Beattie is observed standing on a chair/table using a<br />

megaphone at approximately 6.43 p.m. to introduce Mr Appleford who<br />

proceeds to make an announcement;<br />

whilst the announcement is being made the protestors are chanting;<br />

Inspector Beattie makes a further announcement at approximately 6.48<br />

p.m. regarding the protestors trespassing and requesting them to leave<br />

whilst the chanting continues;<br />

Inspector Beattie makes further announcements at approximately 6.50<br />

p.m., 6.52 p.m. and 6.54 p.m. that the protestors are trespassing and<br />

are required to leave whilst the chanting continues;<br />

9 DECISION

POMT members file into QV Square and form a line in front <strong>of</strong> the<br />

protestors line at the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s and in doing so Mr<br />

<strong>Anderson</strong> is bumped out <strong>of</strong> the way;<br />

Senior Sergeant Falconer is observed approaching Ms Kenway;<br />

POMT members form arrest teams and proceed to arrest Ms Kenway,<br />

Mr Small, Mr Hassan and Mr Ridgewell;<br />

prior to and after the initial arrests various speeches are made by<br />

protestors on megaphones and repetitive chanting is heard;<br />

after the initial arrests Senior Sergeant Falconer is observed at<br />

approximately 6.58 p.m. walking part way along the line <strong>of</strong> protestors in<br />

front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s;<br />

shortly thereafter, the police line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's push the line<br />

<strong>of</strong> protestors out towards the Marquee in QV Square and towards the<br />

Lonsdale Street exit;<br />

approximately 20-25 protestors are then observed to sit down in front <strong>of</strong><br />

“Della Nonna Ristorante” to the southern side <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s;<br />

Inspector Beattie makes two further announcements to that group to<br />

leave at approximately 7.17 p.m. and 7.19 p.m. and further arrests are<br />

then made;<br />

protestors are then observed moving down Artemis Lane towards<br />

Russell St.<br />

16. Mr Appleford gave evidence that once the protestors arrived at QV the police<br />

prevented access to Max Brenner's by “blocking” Red Cape Lane and forming<br />

a line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s facing QV Square. He told the court that the<br />

decision to block the laneway was made by the police in consultation with QV<br />

management. In cross-examination, he agreed with the suggestion that it was<br />

the police action that prevented access by members <strong>of</strong> the public to Max<br />

Brenner’s but added that the public were impeded from entering the store by<br />

both the protestors and police. He also agreed that during the demonstration<br />

customers were inside Max Brenner’s, at the tables outside Max Brenner's in<br />

10 DECISION

Red Cape Lane and that he observed some customers leaving the shop via<br />

the door on Red Cape Lane.<br />

17. Ms Fleming told the court that as soon as the protestors arrived at QV the<br />

police formed a line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s facing the Square and they also<br />

formed a line at the bottom <strong>of</strong> Red Cape Lane. She gave evidence that she<br />

observed protestors pushing backwards against the police line in front <strong>of</strong> Max<br />

Brenner’s and that the shop “closed” its doors for the duration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

demonstration although she observed customers inside the shop and at the<br />

tables outside on Red Cape Lane. She told the court that she was not aware<br />

that the police would form a line across Red Cape Lane near Swanston<br />

Street. She said that she was aware that they would be forming a line in front<br />

<strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s as they had requested that the shop remove tables, chairs<br />

and barriers from that location. Ms Fleming told the court that it was her<br />

understanding that the purpose <strong>of</strong> the police line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's was<br />

to allow the protestors to go up to the line but not beyond it.<br />

18. Inspector Beattie gave evidence that he observed protestors pushing against<br />

the police line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's and therefore he directed that the<br />

police line be reinforced. In his opinion, the actions <strong>of</strong> the protestors did not<br />

allow Max Brenner’s to continue to operate as it was physically difficult for<br />

people to enter the shop because <strong>of</strong> the police lines in place which he<br />

established to stop the protestors “invasion” <strong>of</strong> the shop. He confirmed that<br />

he instructed Senior Sgt Falconer to approach Ms Kenway to ask her to<br />

request that the protestors leave QV. He also confirmed that he gave<br />

directions to the police to use force to move the line <strong>of</strong> protestors in front <strong>of</strong><br />

Max Brenner’s away, so they were not besetting the premises. He told the<br />

court that after the protestors decided to leave the “sit-in” they had established<br />

to the side <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's they did attempt to return to Max Brenner’s but<br />

the police prevented them from doing so. He told the court that once the<br />

police had moved the protestors from QV Square it was “rehabilitated”.<br />

Inspector Beattie also gave evidence that the police action on the night was<br />

dependent on the behaviour <strong>of</strong> the protestors and the fact that the line <strong>of</strong><br />

protestors in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's was pushing against the police line was<br />

the primary reason he gave instructions to arrest the protestors rather than the<br />

trespass issue as he considered their actions to be an insidious form <strong>of</strong><br />

11 DECISION

assault. He told the court that, but for that action by the protestors, he may<br />

have allowed the demonstration to continue longer.<br />

19. In cross-examination, Inspector Beattie told the court that it was the decision<br />

<strong>of</strong> QV management to request the protestors to leave. He told the court that<br />

the police decided to put a line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's to keep the protestors<br />

out and to stop it being “invaded”. He gave evidence that in his opinion, the<br />

police line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's was passive but the protestors were<br />

pushing back against it which required the police to reinforce the line to<br />

maintain their position. He agreed that the police decided to form a line<br />

across Red Cape Lane near Swanston Street for operational reasons.<br />

20. Senior Sergeant Falconer gave evidence that the initial police line in front <strong>of</strong><br />

Max Brenner's was two deep with the protestors line being four to five deep.<br />

He said that in order to stop the “surge” by the protestors he increased the<br />

police line to three deep to prevent the protestors breaking through the line to<br />

Max Brenner’s. He told the court that he observed approximately 20<br />

customers inside Max Brenner's during the demonstration and a few<br />

customers outside on Red Cape Lane. He gave evidence that he had<br />

previously requested Max Brenner's to have their own security so they could<br />

open and close their doors when required. He told the court that he made the<br />

decision to block Red Cape Lane at the Swanston Street end and agreed that<br />

it was “probable” that members <strong>of</strong> the public could not proceed up Red Cape<br />

Lane because <strong>of</strong> the police line established at that point. He told the court it<br />

would depend on the police on that line exercising their discretion to allow<br />

them to do so. In cross-examination, he agreed that the police did not stop<br />

people from entering Max Brenner's until after the protestors arrived in QV<br />

Square. He also agreed that members <strong>of</strong> the public did move through QV<br />

Square whilst the demonstration was occurring and that he did not receive<br />

any complaints that people were not able to access Max Brenner's. He told<br />

the court that QV management made the decision as to when they wanted the<br />

protestors to leave and that no time frame was set for that to occur. He said<br />

that the police only acted when the protestors refused to leave after being<br />

requested to do so.<br />

21. Mr Shrestha gave evidence that he arranged for an extra security guard to be<br />

on duty at both Melbourne Central and QV that night. He confirmed that on<br />

12 DECISION

police recommendations he arranged for some <strong>of</strong> the outdoor tables and<br />

chairs and barriers to be removed from the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner's. He told the<br />

court that he was prepared to shut and lock both entry and exit doors and that<br />

the security guards role was to screen customers coming into the shop in<br />

order to ensure the safety <strong>of</strong> his staff and customers. He gave evidence that<br />

he placed his security guard on the main door facing Red Cape Lane which<br />

was open prior to the protestors arriving but once they arrived it was closed<br />

and locked. He said that during the demonstration there were approximately<br />

10 to 15 customers inside the shop and some at tables outside the shop on<br />

Red Cape Lane, that new customers could enter, but it was left to the security<br />

guard’s discretion to let them, if he felt they were <strong>of</strong> no danger. He told the<br />

court that at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the demonstration three protestors entered the<br />

shop with one <strong>of</strong> them attempting to chain himself to a table but he was<br />

prevented from doing so and forcibly removed by the police. He recalled that<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> customers left the shop during the demonstration.<br />

22. In cross-examination, Mr Shrestha told the court that when he arrived at QV<br />

there was an existing police line in front <strong>of</strong> the shop and the police had<br />

blocked <strong>of</strong>f Red Cape Lane near Swanston Street. He agreed that in the<br />

statement he made to the police on 19 July 2011 he had said; “we locked the<br />

doors and told the customers if they wanted they could leave and the<br />

protestors arrived soon after”. In cross-examination, he also agreed that<br />

customers could enter or leave the shop if they wished if they were able to get<br />

past the police lines or through QV Square.<br />

23. All <strong>of</strong> the police witnesses who gave evidence and were involved on the police<br />

line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s told the court that the protestors were pushing<br />

against them which required them to push back to maintain their line. SC<br />

Beaumont told the court that he observed protestors on the line “cow kicking”<br />

police members on the line and Leading Senior Constable Richards gave<br />

evidence that his toes were stood on and that his shins were kicked and he<br />

was elbowed to the stomach whilst on the police line.<br />

24. The CCTV and video evidence indicates that a number <strong>of</strong> the accused formed<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the protestors line in front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s. Those depicted are; Mr<br />

Ryan, Mr Tymms, Mr Evans, Mr Crafti, Ms Bolton, Mr Monsalve-Tobon and<br />

Ms Farmer. Those observed using megaphones are; Ms Kenway, Mr<br />

13 DECISION

<strong>Anderson</strong>, Ms Javed, Ms Walsh, Mr Hassan, Mr Ridgewell, Mr Oakley and Ms<br />

Bolton. The repetitive chanting that occurred throughout the demonstration<br />

was; “Free Free Palestine”, “Out, Out, Israel Out”, “Max Brenner you can’t<br />

hide, you’re supporting genocide”, “Occupation No More, Israel is a puppet<br />

State”, “Israel Out, USA, How many kids have you killed today?”, and, after<br />

the POM team arrived in the Square; “This is not a Police State, We have the<br />

Right to Demonstrate”.<br />

25. Shortly after the protestors arrived in the Square, Ms Kenway is observed on<br />

the megaphone and heard to say; “What we are going to do now is spread<br />

right across so we need an even row <strong>of</strong> people right across in front <strong>of</strong> Max<br />

Brenner’s, because we want to shut this store down” and then, “So we need<br />

one line right across, right up to the edge <strong>of</strong> Grill’d. Okay, I don’t think people<br />

are getting the concept. There is sort <strong>of</strong> the bulk <strong>of</strong> people up this end. Let’s<br />

move, come down, come down, that’s it”. After there appears to be a<br />

strengthening <strong>of</strong> the police line, Ms Kenway is observed on a megaphone and<br />

heard to say; “Okay, we are going to stand here because the police are trying<br />

to move us on, and I think that we need to say that we are not going to move<br />

on tonight”. Ms Kenway is also observed and heard to say; “to everyone who<br />

is blockading the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner, you need to link your arms and stand<br />

firm, because behind you, there are lines <strong>of</strong> police which are mounting, and<br />

trying to drive us out from here. And I think we need to stand firm and defend<br />

our democratic right to make our voice heard in Australia today”. Mr <strong>Anderson</strong><br />

is also observed and heard to say; “We’ve been told police are arresting<br />

people” and, “We’re gonna stay here, we’re not moving on. We’re not gonna<br />

let the police move us on. We are having a non violent protest and they have<br />

no reason to push us. Do you understand?”. Other statements can also be<br />

heard which include; “We are not your targets, we are a non violent<br />

movement, and we would appreciate it if you would just settle down please<br />

and refrain from violence” and “we are here for a peaceful non violent<br />

demonstration. There’s absolutely no need to push anybody. We are here<br />

peacefully”.<br />

“No-Case” Submissions<br />

26. The test to be applied in a “no-case” submission is the same in a contested<br />

summary hearing as it is in a criminal trial. The High <strong>Court</strong> in May v<br />

14 DECISION

O’Sullivan 1 said;<br />

“When, at the close <strong>of</strong> the case for the prosecution, a submission is<br />

made that there is “no case to answer”, the question to be decided is not<br />

whether on the evidence as it stands the defendant ought to be convicted, but<br />

whether on the evidence as it stands he could lawfully be convicted. This is<br />

really a question <strong>of</strong> law”.<br />

27. In Doney v The Queen 2 the High <strong>Court</strong> held;<br />

“ if in a criminal trial there is evidence (even if tenuous or inherently<br />

vague) which can be taken into account by the jury and that evidence is<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> supporting a verdict <strong>of</strong> guilty, the matter must be left to the jury.<br />

The judge has no power to direct the jury to enter a verdict <strong>of</strong> not guilty on the<br />

ground that, in his view, a verdict <strong>of</strong> guilty would be unsafe or unsatisfactory”.<br />

28. In Attorney-General’s Reference (No.1 <strong>of</strong> 1983) 3 the Full <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> the<br />

1 (1955) 92 CLR 654 at 658.<br />

2 (1990) 171 CLR 207.<br />

Supreme <strong>Court</strong> said;<br />

“The question whether the Crown has excluded every reasonable<br />

hypothesis consistent with innocence is a question <strong>of</strong> fact for the jury and<br />

therefore, if the Crown has led evidence upon which the accused could be<br />

convicted, a trial judge should not rule that there is no case to answer or direct<br />

the jury to acquit simply because he thinks that there could be formulated a<br />

reasonable hypothesis consistent with the innocence <strong>of</strong> the accused which the<br />

Crown has failed to exclude. Similarly a trial judge should not rule that there<br />

is no case for the accused to answer because he has formed the view that, if<br />

the decision on the facts were his and not the jury’s, he would entertain a<br />

reasonable doubt as to the guilt <strong>of</strong> the accused. It is always a question for the<br />

jury whether a reasonable doubt exists as to the guilt <strong>of</strong> the accused and as<br />

Menzies, J. explained in Plomp’s Case, in a case based on circumstantial<br />

evidence, the necessity to exclude reasonable hypothesis consistent with<br />

innocence is no more than an application to that class <strong>of</strong> case <strong>of</strong> the<br />

requirement that the case be proved beyond reasonable doubt.<br />

Where the same tribunal is judge both <strong>of</strong> law and fact the tribunal may be<br />

15 DECISION

satisfied that there is a case for an accused to answer and yet, if the accused<br />

chooses not to call any evidence, refuse to convict on the evidence. That this<br />

is the correct logical analysis appears clearly from May v O’Sullivan. There is<br />

no distinction to be drawn between cases sought to be proved by<br />

circumstantial evidence and other cases”.<br />

29. In applying these principles, the court must determine on the facts <strong>of</strong> this case<br />

as found and the applicable law, whether at the completion <strong>of</strong> the prosecution<br />

case, it has proved beyond reasonable doubt each <strong>of</strong> the necessary elements<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fences alleged to have been committed by each <strong>of</strong> the accused.<br />

Did the protestors actions constitute the <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> wilfully and without<br />

lawful authority besets any premises contrary to S 52 (1A) <strong>of</strong> the Act?<br />

30. S 52 (1A) provides;<br />

Any person who together with others wilfully and without lawful authority besets any premises,<br />

whether public or private, for the purpose and with the effect <strong>of</strong> obstructing, hindering, or<br />

impeding by an assemblage <strong>of</strong> persons the exercise by any person <strong>of</strong> any lawful right to<br />

enter, use, or leave such premises shall be guilty <strong>of</strong> an <strong>of</strong>fence.<br />

31. All <strong>of</strong> the accused are charged with committing this <strong>of</strong>fence at QV on 1 July<br />

2011 from approximately 6.30 p.m. The prosecution are required to establish<br />

that;<br />

3 [1983] 2 VR 410 at 415-6.<br />

i. Max Brenner’s Chocolate Bar was beset;<br />

ii. each <strong>of</strong> the accused beset the shop with others;<br />

iii. that it was beset wilfully and without lawful authority;<br />

iv. that it was beset for the purpose and with the effect <strong>of</strong> obstructing,<br />

hindering or impeding by an assemblage <strong>of</strong> persons the exercise by<br />

any persons <strong>of</strong> a lawful right to enter, use or leave Max Brenner’s<br />

Chocolate Bar.<br />

16 DECISION

32. The word “beset” is not defined in the Act. The Concise Oxford Dictionary<br />

defines it to mean; “hem in, occupy, to make impassable”. The Australian<br />

Concise Oxford Dictionary defines it as; “attack or harass persistently,<br />

surround or hem in, cover around with”. The Oxford English Dictionary<br />

defines it as; “to set about, surround, to set or station around, to surround with<br />

hostile intent, to surround, encircle, cover round, to set upon or assail on all<br />

sides, to invest or surround, to besiege, to occupy so as to prevent anyone<br />

from passing, to circumvent, entrap, catch, to encompass, surround, assail,<br />

possesses detrimentally”. The Macquarie Dictionary defines it as; “to attack on<br />

all sides, assail, harass, to surround, hem in”.<br />

33. The parties were not able to provide the court with any reported criminal<br />

4 [1986] VR 383.<br />

decisions involving the <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> beset premises. There are however,<br />

decisions involving the tort <strong>of</strong> Nuisance where the word “besetting” has been<br />

considered in an industrial context. In Dollar Sweets Pty Ltd v Federated<br />

Confectioners Association <strong>of</strong> Australia 4 , employees <strong>of</strong> the plaintiff company<br />

and <strong>of</strong>ficials from the defendant union formed and enforced a picket outside<br />

the plaintiff’s factory. Their actions obstructed the passage <strong>of</strong> vehicles to the<br />

plaintiff’s premises which prevented a truck driver from Rowntree Hoadley<br />

from delivering 2 tonnes <strong>of</strong> material to the company. The plaintiff applied for<br />

and was granted an interlocutory injunction against the nine named<br />

defendants. Murphy J said; “I am also satisfied that the acts <strong>of</strong> all the<br />

defendants which now have been repeatedly performed over many months<br />

cannot be considered to be a lawful form <strong>of</strong> picketing, but amount to a<br />

nuisance involving, as they do, obstruction, harassment and besetting. The<br />

form <strong>of</strong> picketing which the evidence discloses here is not peaceful but<br />

amounts clearly to interference with the rights <strong>of</strong> a person wishing to enter or<br />

at least to proceed and make deliveries or take supplies to or from the<br />

plaintiff's premises. In fact, so <strong>of</strong>ten as they are able, the defendants<br />

physically prevent persons and vehicles from approaching and entering the<br />

17 DECISION

plaintiff's premises. This, as I have said, is done by obstruction, threats and<br />

besetting, the latter meaning, in this context, to set about or surround with<br />

hostile intent. Besetting is appropriately a term applied to the occupation <strong>of</strong> a<br />

roadway or passageway through which persons wish to travel, so as to cause<br />

those persons to hesitate through fear to proceed or, if they do proceed, to do<br />

so only with fear for their own safety or the safety <strong>of</strong> their property”.<br />

34. The decision <strong>of</strong> Murphy J was referred to by the Full <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Supreme<br />

<strong>Court</strong> in Animal Liberation (Vic) Inc and Anor v Gasser & Anor 5 . In this case,<br />

the appellants and others demonstrated outside the respondents circus in<br />

order to dissuade members <strong>of</strong> the public from attending the performances <strong>of</strong><br />

that circus. It was alleged that they were hostile and argumentative and they<br />

obstructed patrons by forcing them to walk the gauntlet <strong>of</strong> shouting<br />

demonstrators who were waving placards so as to obstruct their entrance to<br />

the ticket <strong>of</strong>fice. The trial judge ordered an interlocutory injunction which<br />

included restraining the demonstrators from conducting demonstrations. The<br />

appellants argued in the Full <strong>Court</strong> that “picketing” did not become a nuisance<br />

unless there is a besetting, and that there is not a besetting unless there is a<br />

surrounding with hostile intent. The Full court said; 6 “We think it clear that a<br />

besetting is only one <strong>of</strong> the ingredients that may make a picketing into a<br />

nuisance, and that a besetting may include, for example, lining up so as to<br />

compel would-be patrons to “walk the gauntlet” <strong>of</strong> shouting picketers, so as to<br />

cause such patrons to hesitate through fear to proceed or, if they do proceed,<br />

to do so only with fear for their safety or fear <strong>of</strong> harmful effects upon the<br />

accompanying children. A besetting includes a surrounding with hostile<br />

demeanour so as to put in fear <strong>of</strong> safety”. The Full <strong>Court</strong> held that the<br />

evidence justified interlocutory injunctions.<br />

35. There are a number <strong>of</strong> English authorities which have considered the meaning<br />

5 [1991] 1 VR 51.<br />

6 Page 58.<br />

<strong>of</strong> “watching and besetting” premises but they have also arisen in the context<br />

18 DECISION

<strong>of</strong> industrial picket lines. The only case found which arose in the criminal<br />

context is DPP v Fidler 7 which involved two defendants who were opposed to<br />

abortion, standing outside a clinic with the intent to dissuade women attending<br />

the clinic from having their pregnancies terminated. They were charged with<br />

“watching and besetting” the clinic contrary to S 7 <strong>of</strong> the Conspiracy and<br />

Protection <strong>of</strong> Property Act 1875. S 7 made it an <strong>of</strong>fence to compel others to<br />

“watch or beset” places or businesses. The court held that the words “with a<br />

view to compel” meant that an essential ingredient <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fence was<br />

compulsion and not mere persuasion and that in the absence <strong>of</strong> evidence that<br />

anyone was prevented from having an abortion meant that no <strong>of</strong>fence was<br />

committed. The court also noted that the means employed to implement the<br />

purpose were confined to verbal abuse and no physical force was used or<br />

threatened. On the basis that “watching and besetting” occurred for the<br />

purpose <strong>of</strong> persuasion as opposed to coercion meant that a breach <strong>of</strong> the<br />

criminal law did not occur.<br />

36. In the present case, only Mr Ryan, Mr Tymms, Mr Evans, Mr Crafti, Ms Bolton,<br />

Mr Monsalve-Tobon and Ms Farmer are seen on CCTV or police video to form<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the protest line at the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s. The other accused are<br />

observed to be at various locations in the middle <strong>of</strong> QV Square during the<br />

demonstration. It is not contended by the prosecution that the “sit in” to the<br />

side <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s near the end <strong>of</strong> the demonstration would constitute<br />

besetting <strong>of</strong> the premises. For the reasons that follow, it is not necessary for<br />

me to determine whether the actions <strong>of</strong> the protestors not involved in the line<br />

can be considered as “acting in concert” with those who formed part <strong>of</strong> it.<br />

37. It is not in dispute that at the time the protestors arrived in QV Square the<br />

7 [1992] 1 WLR 91.<br />

police were forming a line across the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s extending across<br />

Red Cape Lane to the “Grill’d” restaurant in order to, according to Inspector<br />

Beattie, “stop the protestors invasion <strong>of</strong> the shop”. Within a few minutes <strong>of</strong><br />

19 DECISION

their arrival the police also formed a solid line across the bottom <strong>of</strong> Red Cape<br />

Lane near Swanston St. It is also not in dispute that the police decided to re-<br />

inforce their line at the front <strong>of</strong> Max Brenner’s because <strong>of</strong> the actions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

protest line in pushing backwards against them for intermittent periods <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

The CCTV footage indicates that it was the police line across Red Cape Lane<br />

near Max Brenner’s that prevented members <strong>of</strong> the public from proceeding<br />

down the Lane towards Swanston St or into Max Brenner’s, if they so chose.<br />

Although the protest line extended across Red Cape Lane, there is no<br />

evidence that the protest line prevented anyone from proceeding past it. The<br />

CCTV footage also indicates that once the police formed a line across the<br />

bottom <strong>of</strong> Red Cape Lane, the only movement <strong>of</strong> members <strong>of</strong> the public were<br />

those seen leaving Max Brenner’s or other shops in the Lane. Members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

public were prevented by that police line from proceeding up Red Cape Lane<br />

towards Max Brenner’s and QV Square.<br />

38. The CCTV footage also indicates that members <strong>of</strong> the public moved freely<br />

through the protestors in QV Square and one gentleman also engaged in<br />

debate with a number <strong>of</strong> the protestors. In my opinion, it can not be said that it<br />

was the actions <strong>of</strong> the protestors that caused any obstruction, hindering or<br />

impediment to members <strong>of</strong> the public from entering Max Brenner’s, if they<br />

chose to do so. In reality, and notwithstanding Ms Kenway’s message to the<br />

protestors who were “blockading” the store “because we want to shut this<br />

store down”, it was the establishment <strong>of</strong> the police lines at the front <strong>of</strong> Max<br />

Brenner’s extending across Red Cape Lane and at the other end <strong>of</strong> Red Cape<br />

Lane that caused the obstruction, hindrance and impediment to members <strong>of</strong><br />

the public who may have wished to exercise their lawful right to enter or use<br />

the premises.<br />

39. Furthermore, as depicted on the CCTV footage, customers remained inside<br />

and outside Max Brenner’s while the demonstration occurred. Apart from what<br />

appeared to be a robust and vigorous debate with the gentleman referred to,<br />

20 DECISION

there is no evidence <strong>of</strong> any “hostile intent” by any <strong>of</strong> the protestors towards<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the public in QV Square or at the outside tables at Max Brenner’s.<br />

The protestors did not prevent anyone from leaving the shop and there were a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> customers who left the shop and proceeded down Red Cape Lane<br />

during the protest without any interference by the protestors. The evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

Mr Shrestha was to the effect that once the protestors arrived the doors were<br />

shut and locked and that it was left to their security guard as to whether he<br />

would allow customers to enter.<br />

40. In these circumstances, the charges against all accused <strong>of</strong> besetting the<br />

premises is not made out. They did not surround the premises with hostile<br />

intent or demeanour nor did their actions obstruct, hinder or impede any<br />

member <strong>of</strong> the public who wished to enter, use or leave Max Brenner’s<br />

Chocolate Bar. Therefore, I uphold the no-case submissions in relation to this<br />

charge and will dismiss the charge laid under S 52 (1A) against each<br />

accused.<br />

Did the accused wilfully trespass in a “public place” and neglect or<br />

refuse to leave after being warned to do so by the owner, occupier or a<br />

person authorised by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> the owner or occupier contrary to S<br />

9 (1)(d) <strong>of</strong> the Act?<br />

41. The relevant statutory provisions is;<br />

S 9 (1) Any person who—<br />

(d) wilfully trespasses in any public place other than a Scheduled public place and<br />

neglects or refuses to leave that place after being warned to do so by the owner occupier or a<br />

person authorized by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> the owner or occupier;<br />

shall be guilty <strong>of</strong> an <strong>of</strong>fence.<br />

(1A) In any proceedings for an <strong>of</strong>fence against subsection (1) the statement on oath <strong>of</strong> any<br />

person that he is or was at any stated time the owner or occupier <strong>of</strong> any place or a person<br />

21 DECISION

authorized by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> the owner or occupier there<strong>of</strong> shall be evidence until the contrary<br />

is proved by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> the accused that such person is or was the owner or occupier <strong>of</strong><br />

that place or a person authorized by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> the owner or occupier there<strong>of</strong> (as the case<br />

requires).<br />

(1B) A person may commit an <strong>of</strong>fence against paragraph (d), (e), (f) or (g) <strong>of</strong> subsection<br />

(1) even though he or she did not intend to take possession <strong>of</strong> the place.<br />

(2) For the purposes <strong>of</strong> section 86 <strong>of</strong> the Sentencing Act 1991 the cost <strong>of</strong> repairing or<br />

making good anything spoiled or damaged in contravention <strong>of</strong> this section shall be deemed to<br />

be loss or damage suffered in relation thereto.<br />

(3) Nothing contained in this section shall extend to any case where the person <strong>of</strong>fending<br />

acted under a fair and reasonable supposition that he had a right to do the act complained <strong>of</strong><br />

or to any trespass (not being wilful and malicious) committed in hunting or the pursuit <strong>of</strong> game.<br />

42. S 3 defines “public place” to include and apply to, relevant to this matter;<br />

(a) any public highway road street bridge footway footpath court alley passage or<br />

thoroughfare notwithstanding that it may be formed on private property;<br />

(o) any open place to which the public whether upon or without payment for admittance<br />

have or are permitted to have access; or<br />

(p) any public place within the meaning <strong>of</strong> the words "public place" whether by virtue <strong>of</strong><br />

this Act or otherwise.<br />

43. Schedule 1 lists the Scheduled public places as:<br />

SCHEDULED PUBLIC PLACES<br />

1. Land used for the purposes <strong>of</strong> a Government school within the meaning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Education and Training Reform Act 2006.<br />

2. Premises or place where a children's service within the meaning <strong>of</strong> the Children's<br />

Services Act 1996 operates in respect <strong>of</strong> which the Secretary within the meaning <strong>of</strong><br />

22 DECISION

that Act provides grants, payments, subsidies or other financial assistance.<br />

3. Premises that are a residential service, residential institution or residential treatment<br />

facility within the meaning <strong>of</strong> the Disability Act 2006.<br />

4. Premises that are an approved mental health service within the meaning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mental Health Act 1986.<br />

5. Land held or managed by a cemetery trust <strong>of</strong> a public cemetery to which the<br />

Cemeteries and Crematoria Act 2003 applies.<br />

6. Premises or place where an education and care service within the meaning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Education and Care Services National Law (<strong>Victoria</strong>) operates in respect <strong>of</strong> which the<br />

Regulatory Authority within the meaning <strong>of</strong> that Law provides grants, payments,<br />

subsidies or other financial assistance.<br />

44. All <strong>of</strong> the accused are charged with contravening S 9(1)(d) <strong>of</strong> the Act. The<br />

prosecution are required to prove that;<br />

(i) each <strong>of</strong> the accused trespassed in any place other than a scheduled<br />

public place;<br />

(ii) each <strong>of</strong> the accused did so wilfully;<br />

(iii) each <strong>of</strong> the accused was warned to leave the QV site by the owner/<br />

occupier or a person authorised by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> the owner or<br />

occupier;<br />

(iv) each <strong>of</strong> the accused neglected or refused to leave after being so<br />

warned.<br />

45. In support <strong>of</strong> the charges the prosecution rely on the evidence given by;<br />

Ms Fleming; that the property including the Square and laneways are<br />

private property; (although she described it as “an unusual place<br />

23 DECISION

ecause it is a public place that is privately owned”);<br />

Ms Fleming; that the S 173 Agreement provides that QV has the<br />

control, care and management <strong>of</strong> the public areas which includes the<br />

Square and laneways;<br />

Ms Fleming; that in her position as General Manager <strong>of</strong> QV<br />

Management, she had authority from the owners to manage the site<br />

and to remove people from the site who were disruptive or threatening<br />

the business <strong>of</strong> the retail tenants;<br />

Ms Fleming; that she gave authority to the <strong>Victoria</strong> Police in her letter to<br />

Inspector Beattie dated 1 July to remove protestors if they were<br />

requested to leave the site and did not do so;<br />

Mr Appleford, Inspector Beattie, Senior Sgt Falconer and Ms Fleming<br />

as to the placing and contents <strong>of</strong> the Conditions <strong>of</strong> Entry signage<br />

placed in and around QV and the contents <strong>of</strong> and announcements<br />

made by Mr Appleford, Inspector Beattie and Senior Sgt Falconer to<br />

the protestors at various times during the demonstration that they were<br />

trespassers and were required to leave;<br />

The video footage to the effect that both Ms Kenway and Mr <strong>Anderson</strong><br />

were aware <strong>of</strong> the requests made for the protestors to leave the site by<br />

informing the protestors on megaphones that; “the police are trying to<br />

move us on” and “We’re gonna stay here, we’re not moving on. We’re<br />

not gonna let the police move us on”; and<br />

Sgt Nash, concerning the distribution <strong>of</strong> the Notice from Inspector<br />

Beattie to a number <strong>of</strong> protestors, including; Ms Kenway, Mr Oakley<br />

and Mr Hassan outside the State Library prior to the demonstration at<br />

QV about what behaviour would not be permitted on the property.<br />

46. QV Square and the laneways on the site are subject to a covenant between<br />

24 DECISION

the owners <strong>of</strong> the property and Melbourne City Council pursuant to S 173 <strong>of</strong><br />

the Planning and Environment Act 1987. S 173 <strong>of</strong> the Act provides that;<br />

(1) A responsible authority may enter into an agreement with an owner <strong>of</strong> land in the area<br />

covered by a planning scheme for which it is a responsible authority.<br />

(2) A responsible authority may enter into the agreement on its own behalf or jointly with<br />

any other person or body.<br />

47. S 174 <strong>of</strong> the Act provides that;<br />

(1) An agreement must be under seal and must bind the owner to the covenants specified in<br />

the agreement.<br />

The agreement made between the owners <strong>of</strong> QV and the Melbourne City<br />

Council is registered on the Title pursuant to the Transfer <strong>of</strong> Land Act 1958.<br />

For the purposes <strong>of</strong> these proceedings, the relevant provisions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

agreement are;<br />

5.1 QV must keep:<br />

(a) the Lanes open to the public 24 hours a day and 7 days a week in a<br />

manner which is reasonably analogous to Comparable Lanes; and<br />

(b) the QV Square open to the public 24 hours a day and 7 days a<br />

week in a manner which is reasonably analogous to Comparable<br />

Squares.<br />

5.4 (a) Subject to the rights <strong>of</strong> the Council under this agreement and the<br />

obligations <strong>of</strong> QV under this agreement, QV has the control, care and<br />

management <strong>of</strong> the Public areas including all aspects <strong>of</strong> traffic.<br />

(b) Subject to QV complying with its obligations under this agreement,<br />

the Council does not object to QV temporarily closing or interfering with<br />

public pedestrian traffic to Public Areas where the closure or<br />

25 DECISION

interference is reasonably required due to any works, alterations or<br />

other activities required to be carried out by QV in accordance with this<br />

agreement.<br />

48. In my opinion, on the basis <strong>of</strong> this agreement, QV Square and the laneways<br />

fall within the definition <strong>of</strong> “public place” in S 3 <strong>of</strong> the Summary Offences Act<br />

as members <strong>of</strong> the public have access as <strong>of</strong> right 24 hours per day, 7 days a<br />

week subject to the limited exceptions in 5.4 (b). It is therefore necessary to<br />

consider the rights and obligations <strong>of</strong> members <strong>of</strong> the public who wish to<br />

access QV Square and the owners/occupiers <strong>of</strong> the QV site.<br />

49. S 9 (1) imposes different trespass <strong>of</strong>fences which distinguish between private<br />

places, Scheduled public places (as listed in Schedule 1) and public places.<br />

50. Prior to an amendment in 1997, S 9 (1)(d) referred to “place” with the<br />

amendment confining its application to “public places” other than a Scheduled<br />

public place. The other trespass categories are contained in (1)(e), (1)(f) and<br />

(1)(g), with (1)(g) applicable to all places (whether private or public) and (1)(e)<br />

and (1)(f) only applying to private places and Scheduled public places.<br />

Furthermore, S 9 distinguishes between situations where the owner/occupier<br />

must give authority (express or implied) for a person to enter, (sub section(e)),<br />

and public places, (sub section (d)), where authority to enter is not required<br />

and accordingly the owner/occupier cannot refuse or prohibit entry.<br />

51. In my opinion, the owners <strong>of</strong> QV and therefore QV management, by virtue <strong>of</strong><br />

the Square and laneways being subject to the S 173 Planning and<br />

Environment Act agreement and therefore a “public place” by virtue <strong>of</strong> S 3 <strong>of</strong><br />

the Summary Offences Act, did not have the legal authority to apply<br />

conditions on members <strong>of</strong> the public who wished to enter QV Square or the<br />

laneways on the site.<br />

52. In order to contravene S 9 (1)(d), the accused must be categorised as wilful<br />

trespassers and they must be found to have neglected or refused to leave<br />

26 DECISION

after being warned by the appropriate person to do so. 8 The prosecution<br />

submitted that the accused entered QV “without lawful excuse” or did so<br />

“wilfully”, or without a legitimate purpose and refused to leave after being<br />

requested to do so by Mr Appleford, on behalf <strong>of</strong> the owners/occupiers <strong>of</strong> QV.<br />

53. The accused jointly submitted that “wilful trespass” should be interpreted to<br />

mean entering or being in a public place, with the intention to commit a<br />

criminal <strong>of</strong>fence. In support <strong>of</strong> this submission, the accused relied on the<br />

decision <strong>of</strong> Ormiston J in Bergin v Brown. 9 In that case, the applicant was<br />

charged with committing an <strong>of</strong>fence pursuant to S 9 (1)(c) <strong>of</strong> the Summary<br />

Offences Act 1966 in that he “wilfully damaged property”, being a car. The<br />

court was required to determine the proper meaning <strong>of</strong> the word “wilfully”.<br />

After reviewing numerous decisions His Honour held that; “to satisfy the test<br />

<strong>of</strong> “wilfully” damaging property one must show either direct intention to cause<br />

damage or recklessness on the part <strong>of</strong> the accused as to the consequences <strong>of</strong><br />

his acts”.<br />

54. The accused submitted that in the context <strong>of</strong> this case, wilful trespass must<br />

mean something more than entering QV without permission <strong>of</strong> the<br />

owners/occupiers or in contravention <strong>of</strong> the terms set by them on the basis<br />

that they cannot limit entry by virtue <strong>of</strong> QV Square being a “public place”.<br />

55. The accused submitted that the demand to leave QV Square by Mr Appleford<br />

was also not capable <strong>of</strong> transforming them from being members <strong>of</strong> the public<br />

with a lawful right to be there to being wilful trespassers on the basis that QV<br />

management does not have authority to request members <strong>of</strong> the public to<br />

leave a “public place” unless they are wilful trespassers. It was submitted that<br />

the announcement by Mr Appleford that the owners/occupiers <strong>of</strong> QV no longer<br />

gave permission for the accused to remain in QV Square because <strong>of</strong> their<br />

expression <strong>of</strong> political opinion cannot render them wilful trespassers as to<br />

8<br />

See Lewis v Hollowood Unreported Ormiston J 3 October 1988 and Latrobe University v Robinson & Pola<br />

[1972] VR 883.<br />

9<br />

[1990] VR 888.<br />

27 DECISION

interpret S 9 (1)(d) as having that purpose and effect would impermissibly limit<br />

their right to “freedom <strong>of</strong> expression” and the right to “peaceful assembly”<br />

which are protected by the Charter <strong>of</strong> Human Rights and Responsibilities Act<br />

2006.<br />

56. S 15 <strong>of</strong> the Charter <strong>of</strong> Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006<br />

provides:<br />

Freedom <strong>of</strong> Expression<br />

(1) Every person has the right to hold an opinion without interference.<br />

(2) Every person has the right to freedom <strong>of</strong> expression which includes the freedom to seek,<br />

receive and impart information and ideas <strong>of</strong> all kinds, whether within or outside <strong>Victoria</strong> and<br />

whether –<br />

(a) orally; or<br />

(b) in writing; or<br />

(c) in print; or<br />

(d) by way <strong>of</strong> art; or<br />

(e) in another medium chosen by him or her.<br />

(3) special duties and responsibilities are attached to the right <strong>of</strong> freedom <strong>of</strong> expression and<br />

the right may be subject to lawful restrictions reasonably necessary –<br />

(a) to respect the rights and reputation <strong>of</strong> other persons; or<br />

(b) for the protection <strong>of</strong> national security, public order, public health or public morality.<br />

57. S 16 <strong>of</strong> the Charter provides:<br />

Peaceful Assembly and freedom <strong>of</strong> association<br />

(1) Every person has the right <strong>of</strong> peaceful assembly.<br />

28 DECISION

(2) Every person has the right to freedom <strong>of</strong> association with the others, including the right to<br />

form and join trade unions.<br />

58. S 7 <strong>of</strong> the Charter provides:<br />

Human rights – what they are and when they may be limited<br />

(1) This Part sets out the human rights that Parliament specifically seeks to protect and<br />

promote.<br />

(2) A human right may be subject under law only to such reasonable limits as can be<br />

demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and<br />

freedom, and taking into account all relevant factors including –<br />

(a) the nature <strong>of</strong> the right; and<br />

(b) the importance <strong>of</strong> the purpose <strong>of</strong> the limitation; and<br />

(c) the nature and extent <strong>of</strong> the limitation; and<br />

(d) the relationship between the limitation and its purpose; and<br />

(e) any less restrictive means reasonably available to achieve the purpose that the<br />

limitation seeks to achieve.<br />

(3) Nothing in this Charter gives a person, entity or public authority a right to limit (to a greater<br />

extent than is provided for in this Charter) or destroy the human rights <strong>of</strong> any person.<br />

59. S 32 <strong>of</strong> the Charter provides:<br />

Interpretation<br />

(1) So far as it is possible to do so consistently with their purpose, all statutory provisions<br />

must be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights.<br />

(2) International law and the judgments <strong>of</strong> domestic, foreign and international courts and<br />

tribunals relevant to a human right may be considered in interpreting a statutory provision.<br />

29 DECISION

(3) This section does not affect the validity <strong>of</strong> –<br />

(a) an Act or provision <strong>of</strong> an Act that is incompatible with a human right; or<br />

(b) a subordinate instrument or provision <strong>of</strong> a subordinate instrument that is<br />

incompatible with a human right and is empowered to be so by the Act under which it<br />

is made.<br />

60. In the Second Reading Speech when introducing the bill, the Attorney-<br />

General, Mr Hulls said; 10<br />

“Importantly, the Charter recognizes that with rights come responsibilities, and<br />

that everyone in the community has a responsibility to respect the human<br />

rights <strong>of</strong> others. The bill explicitly states that nothing in the Charter gives a<br />

person, entity or public authority a right to limit or destroy the human rights <strong>of</strong><br />

any person. In other words, nothing in the Charter may be interpreted as<br />

giving any group or person any right to engage in any activity aimed at<br />

destroying any <strong>of</strong> the rights recognized by the Charter or aimed at limiting<br />

them to a greater extent than is provided for in the Charter. Human rights<br />