ses training resource kit - Government Skills Australia

ses training resource kit - Government Skills Australia

ses training resource kit - Government Skills Australia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

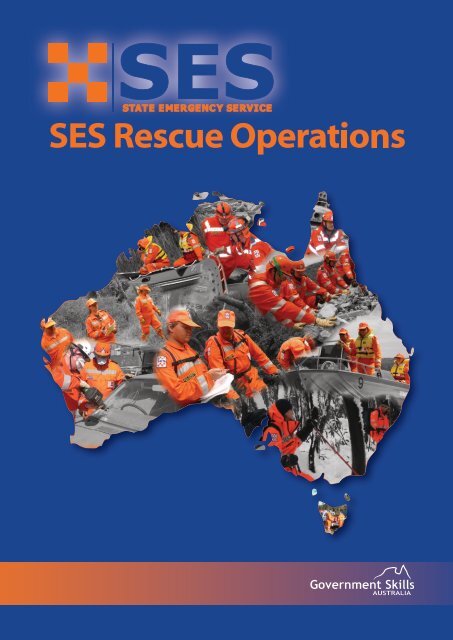

SES<br />

TRAINING RESOURCE KIT<br />

Rescue Operations<br />

Version 1

CONTENTS<br />

Section 4.1 Rescue operations.......................................................... 301<br />

Qualified and appropriate personnel ..........................................................302<br />

Section 4.2 At the scene ................................................................. 305<br />

Scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment.................................................................................305<br />

Gaining access to the scene ....................................................................306<br />

Initial as<strong>ses</strong>sment.................................................................................307<br />

Surface search for casualties ...................................................................307<br />

Incident Marking Systems........................................................................309<br />

Marking systems...................................................................................309<br />

Other Markings ....................................................................................318<br />

Identification structural damage...............................................................318<br />

Structural collapse patterns ....................................................................321<br />

Secondary collapse ...............................................................................328<br />

Common methods of building construction...................................................329<br />

Structural damage ................................................................................330<br />

Section 4.3 Casualty Handling .......................................................... 337<br />

Moving casualties .................................................................................337<br />

Classification of Casualties......................................................................342<br />

Loading a stretcher...............................................................................345<br />

Casualty handling techniques using no equipment ..........................................349<br />

Mixed teams and special stretcher combinations ...........................................355<br />

Moving Stretchers.................................................................................358<br />

Moving stretchers in tight spaces ..............................................................359<br />

Moving stretchers over a gap ...................................................................360<br />

Section 4.4 Operational Debrief........................................................ 365<br />

Operational debriefing...........................................................................365<br />

Progressive Learning and As<strong>ses</strong>sment Record Form – Rescue Operations................373

Section 4.1 Rescue operations<br />

As a member of a rescue team, you may be asked to:<br />

• provide access to, support and remove trapped persons<br />

• undertake body recovery<br />

• provide support to other services, authorities or specialist teams on request.<br />

There are no set rules for tackling every rescue task. However, a rescue is<br />

generally faster and more effective if it follows stages. Below is an example of<br />

five stages for a structural collapse rescue.<br />

Table 1 Stages of structural rescue operation<br />

Stage 1 Clear surface<br />

casualties<br />

Stage 2 Rescue lightly<br />

trapped/easily<br />

accessed<br />

Stage 3 Explore likely<br />

survival points<br />

Stage 4 Selected debris<br />

removal<br />

Stage 5: Total debris<br />

clearance<br />

The first task is to clear surface casualties – those who are<br />

not trapped and are clean of any obstruction or hazard.<br />

Ambulance or first aid personnel normally care for<br />

casualties, but you may be asked to help.<br />

The next task is to rescue those who are lightly trapped<br />

and/or search lightly damaged buildings.<br />

The third stage is to search likely survival points where<br />

people may have taken shelter or refuge and where they<br />

may be trapped, either injured or uninjured.<br />

When casualties are found the rescue team will often have<br />

to remove debris to get to them. The amount of debris<br />

moved depends on:<br />

• the location of the casualty<br />

• the nature of their injuries (if known)<br />

• the layout of the building or structure<br />

• the way in which the building or structure has<br />

collapsed.<br />

The final stage of a structure collapse rescue will be to<br />

methodically strip the site. This stage may be completed<br />

by demolition contractors, rather than emergency services.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 301

WORDS CAN VARY<br />

BUT RESCUE PROCESS<br />

REMAINS<br />

ESSENTIALLY THE<br />

SAME<br />

Another set of words to describe the rescue<br />

stages is based on the acronym<br />

REPEAT:<br />

Reconnaissance and survey<br />

Elimination of utilities<br />

Primary surface search and rescue<br />

Exploration of voids and spaces<br />

Access by selected debris removal<br />

Termination by general debris removal<br />

As you can see, the stages are essentially the same<br />

as the stages mentioned in the example above.<br />

If you are dealing with a structural collapse and missing persons, you will be faced<br />

with decisions based on what you see, smell, touch and hear. Combine this with<br />

limited access and the possibility of foul weather or night operations and any<br />

rescue may look like an enormous task. Good planning and a systematic approach<br />

will break a seemingly impossible problem into manageable pieces.<br />

When one or more rescue teams combine to work at one incident, there has to be<br />

a standardised way to:<br />

• identify work site hazards<br />

• identify the different teams and what they have done<br />

• map landmarks with common symbols.<br />

Once mapping and marking has been established you can systematically remove<br />

casualties in a sensible order by locating, accessing, stabilising and transporting<br />

them to a designated area.<br />

Qualified and appropriate personnel<br />

In any rescue operation, there may be three groups of workers that might be able<br />

to assist. These are:<br />

302 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Survivors<br />

The first group to commence rescue work at a site are usually those survivors who<br />

are able to help. They can potentially do a lot of good but there is always a<br />

danger with inexperienced people doing rescue work.<br />

Sometimes these people are the only hope of survival for many victims but they<br />

could also make injuries worse. They may also get in the way of the trained<br />

rescue teams.<br />

Untrained personnel<br />

The second ‘wave’ of rescue workers are people who have witnessed the event or<br />

are nearby who may be drawn to the site by curiosity or a desire to help. There<br />

may be an advantage in them being less emotionally involved. However, there is<br />

still the danger of them making the situation worse. Unfortunately, many of this<br />

second group are just curious and can disrupt a rescue team’s work. They should<br />

be moved to a place where they will not get in the way or add to the excitement<br />

or anxiety of the rescue.<br />

Trained personnel<br />

The last group to arrive at the scene are usually the trained personnel: the rescue<br />

members, the police, and ambulance or other emergency services personnel. It<br />

takes time for various emergency services to be mobilised and arrive at the scene.<br />

The more quickly they arrive, the quicker trained rescue personnel can manage<br />

the rescue. Well-trained rescue teams know what to do. They know how to use<br />

the available <strong>resource</strong>s and how to direct untrained people to assist in the best<br />

way possible.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 303

Self check<br />

Having completed this section, are you able to:<br />

Understand what you may be asked to do as a member of a rescue team?<br />

Identify and describe rescue stages: REPEAT?<br />

If you have answered NO to any of these questions, ask your trainer for help.<br />

304 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Section 4.2 At the scene<br />

Rescue scenes and operations that SES members may be involved in include:<br />

• rescue from the roof of a house during floods<br />

• rescue lightly trapped surface casualties as a result of a earthquake,<br />

cyclone, accident or building collapse<br />

• rescue from a vehicle accident<br />

• rescue from heights or depths eg cliffs, caves, confined spaces.<br />

Some of the rescues identified above require specialist <strong>training</strong> which is beyond<br />

the scope of this course.<br />

Scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment<br />

For further information consult with your Trainer.<br />

Scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment which could be termed reconnaissance, is primarily the team<br />

leader’s responsibility. However, each member of a rescue team should be trained<br />

in rescue reconnaissance, as the team leader will always need your help.<br />

A scene reconnaissance is a systematic information-seeking process where the<br />

information may be gathered on route to, and on arrival at, the scene. It is used<br />

to develop a picture of the task/s and to assist in determining a course of action.<br />

The type of information sought may include the following:<br />

• any hazards at the scene, eg fallen power lines, downed trees<br />

• access to the scene, road blocks etc<br />

• the extent and type of damage<br />

• availability of occupants/owner/landlord for permission to enter<br />

• estimates of <strong>resource</strong>s required at the scene<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 305

• estimates of time required to complete tasks.<br />

During a scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment you need to get an accurate as<strong>ses</strong>sment of:<br />

• the number and location of casualties<br />

• hazards that might endanger rescuers or survivors<br />

• the extent and type of damage<br />

• ways to gain access to the casualties or tasks<br />

• available <strong>resource</strong>s, both personnel and equipment<br />

• how long the task would take with available <strong>resource</strong>s.<br />

Gaining access to the scene<br />

Access to the scene needs to be undertaken in a safe manner which does not<br />

compromise the safety of those at the scene initially, SES members or members of<br />

the public. Information on access to the scene may be provided through the Team<br />

Leader.<br />

At larger incident scenes there are three (3) zones allocated:<br />

• hot zone: the immediate area of the incident and operation<br />

• warm zone: the stage area for equipment and personnel for enter to the Hot<br />

Zone<br />

• cold zone: the area outside of the Hot and Warm Zones, which is safe for<br />

others at an incident.<br />

Access to the Hot Zone is generally through one designated entry point and only for<br />

personnel directly involved with the incident. Control of entry to the Hot Zone is<br />

through designated personnel on scene who log in and out accordingly.<br />

Personnel who are involved in or preparing for operations in the Hot Zone are able<br />

to access the Warm Zone. Those personnel who are staged (waiting to undertake<br />

tasks or be tasked) will have access to the Warm Zone through a marshal.<br />

The Cold Zone is where rest breaks are taken, media liaison areas and other<br />

functions which contribute to operations.<br />

306 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

The Hot and Warm Zones may be cordoned off as decided by the Incident<br />

Controller.<br />

Initial as<strong>ses</strong>sment<br />

Normally the rescue team would set up the equipment while the Team Leader<br />

would carry out a detailed reconnaissance, preferably with another person.<br />

However, it is essential that every member of a team be trained in scene<br />

as<strong>ses</strong>sment as the Team Leader may be responsible for a number of tasks.<br />

Deployed personnel must be capable of carrying out an effective scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment<br />

and reporting accurate observations back to the Team Leader.<br />

At and around the scene, all sources of information should be used by the team<br />

members undertaking the as<strong>ses</strong>sment. These sources may include, but not be<br />

limited to, the following:<br />

• police<br />

• neighbours<br />

• owners/occupiers<br />

• relatives of the owners/occupiers<br />

• passers by.<br />

Team members should remember that some witnes<strong>ses</strong> may be traumatised by what<br />

they have seen and must be approached and questioned with consideration. Any<br />

verbal information must be written down; do not rely on memory, particularly in<br />

such a stressful situation.<br />

Surface search for casualties<br />

Calling and Listening Procedures<br />

If casualties are conscious a 'calling and listening period' may locate them. The<br />

Officer In Charge (OIC) positions teams along the fringe of the debris near the<br />

position where casualties are thought to be trapped. They lie on the debris and if<br />

possible get their heads close to openings that go down into the debris. The OIC<br />

calls for silence on the site and if necessary asks the Police to ensure that silence<br />

is maintained, while the calling lasts. Each team member in turn is instructed to<br />

call, using terms such as<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 307

• "rescue team working overhead, can you hear me?"<br />

• all listen intently for any answering sound from a trapped casualty and if a<br />

reply or knocking sound is heard each rescuer indicates with an outstretched<br />

arm in the direction from which they think the sound originated<br />

• the OIC, observing the various bearings given by team members, should be<br />

able to estimate the position of the casualty with a good degree of accuracy<br />

• if there is no reply to the rescuers a good tactic is to try knocking on objects<br />

such as steel beams that go deep into the debris. This sound may reach the<br />

casualty even though the calls have failed to do so, and they in turn may be<br />

able to knock in reply<br />

• when contact has been established, the rescuer must question the casualty (if<br />

they are able to speak). The questions should be confined to ones aimed at<br />

receiving information that will help the OIC in forming a strategic plan for the<br />

extrication<br />

• the nature of the casualty's injuries, for instance, is often significant in this<br />

regard. How are they trapped? Are there any openings in the walls in their<br />

vicinity? This latter question is of great importance. A lane cleared through<br />

the debris in a straight line towards the casualty, for instance, may bring the<br />

rescuers up against a blank wall. Such a clearance should be aimed at doors<br />

or windows or other openings formed in the walls by the collapse<br />

• once communication of this kind has been established with a person it should,<br />

as far as it is possible, be maintained for the following reasons:<br />

• help maintain the casualty’s morale, it helps them to withstand<br />

whatever pain and discomfort they may be suffering and may even give<br />

them sufficient hope to keep them alive<br />

• it helps rescuers to work in the right direction - sometimes a difficult<br />

matter in the dark<br />

• the victims, if sufficiently conscious, may be able to give warning of any<br />

displacement or movement in the debris likely to cause them further<br />

injury, or give information of any other casualties who may be located<br />

nearby.<br />

NOTE<br />

Conversation with a trapped person must<br />

always be of a reassuring nature.<br />

308 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Incident Marking Systems<br />

The International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG) developed an<br />

internationally agreed system for marking collapsed structures.<br />

The system normally u<strong>ses</strong> building plans and street maps, but if these are not<br />

available it can be used with sketch maps of the building, which also identify and<br />

label landmarks.<br />

To use the system, you need to establish the building’s orientation, and name the<br />

sides and internal sectors of the building. Internal plans (if available) make this<br />

task much easier.<br />

Marking systems<br />

Three systems of marking are used at rescue incidents.<br />

These marking systems are for:<br />

• site indication<br />

• structure as<strong>ses</strong>sment<br />

• victim location.<br />

Site Identification Marking System<br />

Upon arrival at a structure collapse scene, each structure involved must be<br />

identified and the incident scene secured.<br />

Structural identification and securing the scene involves:<br />

• assigning geographical areas and numbers of each structure<br />

• numbering the sides of each structure<br />

• identifying and marking individual sections within each structure<br />

• designating hot, warm and cold zones for incident operations.<br />

Once this is achieved, the site identification marking system is used to mark,<br />

record and communicate this information to all personnel.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 309

The site identification marking system is particularly useful to the incident<br />

controller. It is an operational briefing tool as well as a tool to ensure that all<br />

structures involved in the collapse are systematically as<strong>ses</strong>sed, hazards are<br />

controlled and surface search and rescue operations are conducted safely and<br />

effectively.<br />

The address side of the structure is defined as SIDE 1. Each other side of the<br />

structure is numbered clockwise from SIDE 1.<br />

Marking structures in a multiple structure collapse area<br />

It is important to clearly identify each separate structure within a geographic area.<br />

The primary method of identification is the existing street name and building<br />

number.<br />

Smith St<br />

900 902 904 906<br />

Bowen St<br />

North<br />

Figure 1 Identify multiple collapsed structures by street name and number<br />

If previously existing street numbers have been obliterated, attempt to re-<br />

establish the numbering system based upon one or more structures that still<br />

display an existing number. Clearly mark the fronts of structures with the assigned<br />

number using ‘international orange’ spray paint. Also indicate the boundary<br />

frontage of individual structures using the spray paint or barrier tape.<br />

Structure as<strong>ses</strong>sment marking system<br />

Structure as<strong>ses</strong>sment marking systems tell a brief story of who did what in a<br />

damaged structure. The markings of the first team are placed on the outside of<br />

the structure, close to the entry point.<br />

310 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)<br />

Brown St

Building sectors<br />

If a second team enters the building they should put their own marks next to the<br />

original markings. No team should ever amend existing marks. If it is necessary to<br />

review the original marks, a separate set must be placed next to the original.<br />

Preliminary identification<br />

The interior of the structure is divided into sectors. Each sector is identified<br />

alphabetically, starting with ‘A’ at the intersection of SIDE 1 and SIDE 2. The<br />

central core, where all four sectors meet, is always Sector E.<br />

Multi-story structures should have each floor clearly identified. If not clearly<br />

discernible, the floors should be numbered as seen from outside. The ground level<br />

floor is designated FLOOR LEVEL 1. Moving upward the next floor is FLOOR LEVEL<br />

2, and so on. The first floor below ground level is called BASEMENT 1, the second<br />

BASEMENT 2, and so on.<br />

Marking a single collapsed structure<br />

All sides of each individual structure involved in a collapse should be numbered,<br />

starting with side one on the street address side of the structure and working<br />

clockwise around each structure.<br />

Side 2<br />

B<br />

Side 3<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 311<br />

E<br />

C<br />

A D<br />

Side 1<br />

Smith St<br />

Side 4

Figure 2 Numbered sides of a collapsed structure<br />

Each structure’s interior should be divided into quadrants. Identify the quadrants<br />

alphabetically and in a clockwise manner starting from the area where side one<br />

and side two perimeters meet.<br />

The central core where all four quadrants meet is designated as quadrant E.<br />

Quadrants do not have to be symmetrical and can be altered to suit the needs of<br />

the incident.<br />

Marking structures without street addres<strong>ses</strong><br />

Collapsed structures with no street address, such as bridges and flyovers, can be<br />

divided into manageable sections along their lengths. The size of sectors will be<br />

based on the incident and geography of the area.<br />

Collapsed Bridge<br />

Sector A Sector B Sector C Sector D<br />

Figure 3 Marking collapsed structures without street addres<strong>ses</strong><br />

Structural As<strong>ses</strong>sment and Search Marking System<br />

The structural as<strong>ses</strong>sment and search marking system is used to indicate hazard<br />

information (for example structure requires shoring/rats found); number of people<br />

found alive and removed; number of people found dead and removed; number of<br />

people unaccounted for; and the location of other victims. The team members, or<br />

an advance reconnaissance team, place signs adjacent to the safe entry point of<br />

the structure prior to the deployment of rescue operations.<br />

Use this marking system also, where appropriate, inside the structure adjacent to<br />

rooms, hallways and stairwells. Team members must be aware of secondary<br />

entrances, which will be signed alike. Any entries not signed in the appropriate<br />

manner should be considered unsafe and dangerous, and should not be used.<br />

312 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Update information as subsequent as<strong>ses</strong>sments are made. Write new information<br />

either below the previous entry or draw a completely new marking box.<br />

Structural as<strong>ses</strong>sment and search marking box<br />

The structural as<strong>ses</strong>sment and search marking system consists of a square box (1 m<br />

x 1 m) drawn using ‘international orange’ paint (tape or crayon may be used to<br />

minimise damage).<br />

1 metre<br />

1 metre<br />

Figure 4 Marking box symbol<br />

Display the relevant information on the outside and inside of the box as follows:<br />

1. Top of square: hazard information (for example, structure requires<br />

shoring/snakes found)<br />

2. Left side of square: number of people found alive and removed<br />

3. Right side of square: number of people found dead and removed<br />

4. Bottom of square: number of people unaccounted for and the<br />

location of other victims<br />

5. Inside the square: G (Go) indicates the structure is safe to enter; NG<br />

(No Go) indicates the structure is not safe for entry; the name of<br />

the Rescue team; the time and date the USAR team entered the<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 313

structure; and the time and date the USAR team exited the<br />

structure.<br />

Figure 5 Structural as<strong>ses</strong>sment and search marking information<br />

NOTE<br />

The finished marking system is circled. This<br />

does not mean that all victims have been<br />

removed from the structure, it simply indicates<br />

that that team has finished its assigned task.<br />

Figure 6 Completed structure marking box<br />

314 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Victim Marking<br />

A key part of the initial search is to locate any victims. Debris in the area may<br />

completely cover or obstruct the location of known or potential victims. Search<br />

teams mark victim locations whenever a known or potential victim is located and<br />

not immediately removed.<br />

During the search function, it is necessary to identify the location of any known or<br />

potential victim. The amount and type of debris in the area may completely cover<br />

or obstruct the location of the known or potential victim. The victim location<br />

markings are made by the Search Team or other individuals conducting search and<br />

rescue operations whenever a known or potential victim is located and not<br />

immediately removed.<br />

The victim location marking system is used to clearly mark the potential and<br />

confirmed locations of victims in the structure collapse area and to indicate<br />

whether they are alive or dead. Markings are made with a high visibility paint,<br />

chalk or crayon.<br />

Place markings as near as practical to a victim and identify the direction and<br />

distance to the victim’s location. If victims can communicate, ask them if they<br />

know of any other victims and where they are or were located. Apply markings to<br />

represent the following information:<br />

a. potential victim(s)<br />

b. victim location<br />

c. confirmed victim(s)<br />

d. extricated live victim(s)<br />

e. extrication of live victims only<br />

f. all victims extricated.<br />

A large "V" is drawn near the location of the known or potential victim. The letter<br />

“L” with a number will denote the number of live victims. The letter “D” with a<br />

number will denote the number of dead victims.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 315

Draw an arrow beside the "V" when the location of a victim has been confirmed<br />

either visually, vocally or hearing specific sounds, which would indicate a high<br />

probability of a victim. This may be done when the victim is initially located or<br />

may need to be done later after some debris removal or use of specialized search<br />

equipment. A canine alert will initially receive the "V" without an arrow to<br />

indicate a potential victim.<br />

If a rescue team is only tasked with the extrication of live casualties then a circle<br />

would be drawn around the "V" and a line drawn through the “L” part of the code<br />

when the last live victim has been extricated from that location. Only when all<br />

victims (live and dead) have been extricated from the site would a horizontal line<br />

be drawn through the “V”, lines drawn through both the “L” and “D” parts of the<br />

code and a circle re-drawn around the “V” to indicate all victims have been<br />

removed from the site.<br />

Potential Victim Location<br />

Confirmed Victim Location<br />

(# OF LIVE VICTIMS) L — 1<br />

(# OF DEAD VICTIMS) D — 2<br />

316 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Extricated Live Victims<br />

(# OF LIVE VICTIMS EXTRICATED) L — 1<br />

(# OF DEAD VICTIMS) D — 2<br />

Extrication of Live Victims only and team moved on<br />

All Victims Extricated<br />

L — 1<br />

D — 2<br />

L — 1<br />

D — 2<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 317

Other Markings<br />

General cordon markings (cordon banners, flagging, etc) are to be used for small<br />

defined area. They can be enlarged to include other non-buildings (ie bridge,<br />

dangerous zones, NBC, security, etc). Large areas may require<br />

barricades/fences/patrol/etc.<br />

Facility:<br />

Figure 8 Marking indicating Operational Work Zone & Hazard Zone<br />

Iconic flags, banners, balloons, etc (must identify team identity, team medical<br />

facility, team CP).<br />

Vehicle:<br />

Vehicles must be marked with team name and function (flag, magnetic sign, etc).<br />

Team and function:<br />

Response team identity (country and team name) by uniform, patch, etc.<br />

Identification structural damage<br />

SES members attend incident where structures, building or homes have been<br />

damaged. To ensure that the appropriate operational activities are undertaken<br />

and safety of all at an operation, SES personnel need to be aware of the following.<br />

318 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Wall Damage<br />

The walls and ceilings of a building can be damaged by:<br />

• the impact of flying debris<br />

• falling trees or branches<br />

• the force of wind and water<br />

• earthquake.<br />

Regardless of the cause of damage, a few simple guidelines are appropriate for all<br />

operations and teams.<br />

Lightly constructed walls are more prone to damage than those of double brick,<br />

block or stone, but this tends to be offset by the fact that lightly-built walls are<br />

generally easier to repair.<br />

In instances where a wall has been penetrated or so badly damaged that the<br />

integrity of the structure has been affected, the immediate area should be<br />

cordoned off as a “no go” zone and advice sought by the owners from a building<br />

engineer.<br />

Where damaged tilt-up panels are involved, it should be remembered that these<br />

are one piece and can be 15 metres or more in height. Any “no go” zones must<br />

take height into account, generally 1.5 times the height of the wall.<br />

Where a small section of wall is suspected to be damaged, it may be possible to<br />

shore up the wall to prevent further damage and to ensure the safety of<br />

operational team members while other work is carried out. This shoring should be<br />

of a temporary nature, designed to meet immediate needs.<br />

Shoring is designed to prevent further movement, not force the section of wall or<br />

ceiling back into place. If this is attempted, further damage may occur. The most<br />

important aspect of shoring is that it can do the job and is secure. If there are any<br />

doubts about the damaged area or the shoring, the area should be designated as a<br />

“no go” zone.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 319

Ceiling Damage<br />

Damage to ceilings is very similar to wall damage, in that it is usually caused by<br />

flying debris, the collapse of the roof and, most commonly, by water/wind damage<br />

following roof damage. The first priority is to repair the roof damage and then, if<br />

possible, stabilise the ceiling to make the building habitable. This may not always<br />

be possible due to the danger from falling material and electrical hazards;<br />

extreme care should be taken when entering an area where the ceiling appears<br />

damaged.<br />

Sometimes the damage to a ceiling may not be obvious except for water marks and<br />

bulging. This may indicate that the ceiling space is full of water and is ready to<br />

collapse. In this situation, holes will need to be made in the ceiling to test this<br />

theory, and to drain the water away. As with all repairs, the owner must be<br />

informed of any plans to carry out such actions.<br />

Another issue with ceiling collapse is the habit of some drug growers to put pots or<br />

trays filled with soil into the roof space, which adds to the weight of an already<br />

damaged ceiling. Occupiers in this situation may not tell rescue teams what is in<br />

the roof space so members need to be aware of the possibility.<br />

Different (or Altered) elevation<br />

Ceilings and walls can become reoriented when structures collapse, stacking them<br />

together and often offsetting the "pancake" effect with the debris forming voids<br />

that make room identification very difficult. For example, surfaces that were once<br />

ceiling and walls can now appear to be floor. As rescuers move into voids to<br />

search, the surface on which they are working cannot be guaranteed as being<br />

stable. As the search proceeds debris will continue to settle and further altered<br />

levels may be encountered throughout the structure.<br />

Interview locals to ascertain who lives in which room and obtain information<br />

about:<br />

• who lives in which rooms or apartments<br />

• what colours are the ceilings, walls and floors<br />

• what furniture and internal items are in the rooms<br />

• what is the potential for occupancy and what hazards are likely.<br />

320 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Before stepping onto surfaces, first probe for false floors and differences in<br />

elevation. Keep in mind that after a building collapse the orientation of floors<br />

may be altered.<br />

An oxygen deficient atmosphere, flooding and toxic or flammable environments<br />

might be encountered by rescuers as they descend below the debris. Atmospheric<br />

monitoring and the elimination of ignition sources are essential. Adequate lighting<br />

and ventilation is necessary and as rescuers move deeper below the surface the<br />

greater the requirement for shoring.<br />

NOTE<br />

Structural collapse patterns<br />

In the World Trade centre bombing a Fire<br />

fighter fell four floors from basement level 2 to<br />

basement level 6 as he stepped through a<br />

doorway.<br />

There are different possible structural collapse patterns involved when structures<br />

are damaged. The type of structural collapse patterns will be based on a number<br />

of factors and it is important that you are able to recognise these in the event that<br />

you and your team are called out to assist with an operation which includes<br />

structural collapse. Types of structural collapse include:<br />

• curtain fall wall collapse<br />

• inward / outward collapse<br />

• lean over collapse<br />

• lean to floor collapse<br />

• angle wall collapse<br />

• pancake floor collapse<br />

• secondary collapse / other building<br />

• inverted, " A " or tent collapse<br />

• " V " collapse<br />

• cantilever collapse<br />

• progressive collapse.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 321

The majority of these structural collapse patterns are based on research and<br />

experience following earthquakes.<br />

Rescue operations which involve personnel to enter structural collap<strong>ses</strong> to search<br />

for and retrieve trapped persons require specialist skills and appropriately<br />

qualified and experienced members to effectively manage and undertake these<br />

operations.<br />

It must be stressed that other collapse patterns and a combination of the<strong>ses</strong><br />

collapse patterns may occur. For example, building collapse following an<br />

explosion is dependent on a large number of factors that may or may not be<br />

predictable.<br />

CHECK THE<br />

NEWSPAPERS<br />

CHECK THE WEB<br />

It may be helpful to refer to photographs of<br />

actual collapse patterns that have recently<br />

occurred following natural and man made<br />

disasters.<br />

Compare and contrast the photographs you find<br />

with the images and diagram on the next few<br />

pages.<br />

322 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Curtain fall wall collapse<br />

A wall made of bricks or blocks falls like a curtain, ie drops straight downward.<br />

Inwards / Outward collapse<br />

A wall made of bricks or blocks falls with the top portion of the wall falling inwards<br />

and the bottom portion of the walls falls outwards.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 323

Lean over collapse<br />

A building collap<strong>ses</strong> to one side.<br />

Lean to Floor collapse<br />

A floor above ground level becomes dislodged from one side of the structure and<br />

falls to the level below.<br />

324 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

90◦ Angle wall collapse<br />

A wall made of masonry, bricks or blocks collap<strong>ses</strong> at a 90 degree angle covering<br />

the ground with the wall for a distance of the height of the wall.<br />

Pancake floor collapse<br />

A floor or ceiling falls flat downwards.<br />

SECONDARY<br />

COLLAPSE / OTHER<br />

BUILDING<br />

The building you are working in/on; or another<br />

building next door collap<strong>ses</strong> causing additional<br />

rescue and scene of operations problems. The<br />

type of collapse following a secondary collapse<br />

may be any of the eleven described, or a<br />

combination of patterns.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 325

"V" Collapse<br />

The floor or ceiling gives way in the centre and falls to the floor below.<br />

Inverted, "A" or Tent Collapse<br />

Resulting in the opposite of the "V" type collapse pattern.<br />

326 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Cantilever Collapse<br />

A piece of floor, ceiling or wall falls landing on a stationary structure and leaving a<br />

large segment hanging over an open area.<br />

Progressive Collapse<br />

There is an initial failure of a single primary support member. A chain reaction of<br />

failures continues in a downward movement.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 327

Secondary collapse<br />

There are a number of indications of the potential for a secondary collapse at a<br />

search and rescue structural collapse incident. The three most common signs that<br />

are likely to be observed are:<br />

• movement in the structure<br />

• visual alertness<br />

• hearing alertness.<br />

Movement in the Structure<br />

• movement in any floor, ceiling and roof<br />

• movement of ornamental shop fronts<br />

• movement of unsupported or non-load bearing walls<br />

• movement of structural beams<br />

• columns and walls out of plumb<br />

• ceiling sagging.<br />

Visual Alertness<br />

• fire consuming location where sprinkler tank is housed<br />

• uneven surface, heavy signs on a section or the whole of the roof<br />

• cracks appearing in the exterior walls<br />

• sagging or bulging walls / chandelier shaking or swaying<br />

• large fire which has been unsuppressed for more than 20 mins involving 2 or<br />

more floors<br />

• walls showing smoke or water seeping through.<br />

Visual clues<br />

• uneven surface, heavy signs on section or whole of the roof<br />

• cracks appearing in the exterior walls<br />

328 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

• sagging or bulging wall or cantilever shaking or swaying<br />

• large fire which has been unsuppressed for more than 20 minutes involving<br />

two or more floors<br />

• smoke or water coming through walls.<br />

Hearing Alertness<br />

• creaking and groaning types of noi<strong>ses</strong> coming from the building/structural<br />

elements<br />

• interior explosions, rumbling noi<strong>ses</strong>, hissing sounds, electrical arcing<br />

• strong winds<br />

• safety warning signals from personnel working on scene.<br />

Audible clues<br />

• creaking and groaning noi<strong>ses</strong> coming from the building or structural elements<br />

• interior explosions, rumbling noi<strong>ses</strong>, hissing sounds, electrical arcing<br />

• strong winds.<br />

Common methods of building construction<br />

There are seven common methods of construction for buildings. The references to<br />

these methods of construction are common throughout <strong>Australia</strong>:<br />

• timber<br />

• light frame (ordinary construction/brick veneer)<br />

• besser block<br />

• reinforced masonry<br />

• un-reinforced masonry<br />

• concrete tilt-up<br />

• reinforced concrete and steel construction.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 329

Structural damage<br />

These construction types will all react differently when subjected to forces that<br />

lead to a structural collapse. The following descriptions will give you some idea<br />

of what to expect, but there may be large variations due to any combination of<br />

factors, but most importantly, the cause of the structural collapse will have the<br />

largest bearing upon how the building reacts.<br />

Timber<br />

eg normal suburban house<br />

• masonry chimneys can crack and collapse into or out from the structure<br />

• chimneys can separate from the walls<br />

• house sliding off foundation<br />

• racking of walls (out of plumb)<br />

• displaced walls<br />

• openings can become out of shape (rectangular to parallelograms)<br />

• masonry veneers can fall off the walls<br />

• offset structure separate from the main structure.<br />

Risks<br />

There is an extreme risk from fire in these structures due to the abundance of<br />

fuel. Due to their relatively lightweight and small size few people are seldom<br />

comprehensively entrapped within timber residential collapsed structure.<br />

Light Frame (Ordinary Construction)<br />

eg larger residential properties<br />

• masonry chimneys can crack and collapse into or out from the structure<br />

• chimneys can separate from the walls<br />

• house sliding off foundation<br />

• racking of walls (out of plumb)<br />

• displaced walls<br />

330 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

• openings can become out of shape (rectangular to parallelograms)<br />

• masonry veneers can fall off the walls<br />

• offset structure separate from the main structure.<br />

Risks<br />

As with timber construction, there is an extreme risk from fire in these structures<br />

however the risk of entrapment in a light frame construction is increased following<br />

a collapsed structure.<br />

Reinforced Masonry<br />

eg older style office blocks and residential buildings<br />

• columns break at intersections with floor beams<br />

• inadequate reinforcement bar and ties do not confine the concrete when<br />

subjected to high shear and tension stres<strong>ses</strong><br />

• short columns in the exterior walls get high shear and tension stres<strong>ses</strong><br />

directed into them by surrounding massive concrete<br />

• bending and punching sheer failure at intersections of a slab (waffle) and<br />

columns<br />

• un-reinforced masonry infill has been known to fall off and often become<br />

displaced from surrounding frames<br />

• weak concrete and poor construction can make all the above conditions worse<br />

and has been known to lead to larger collapse.<br />

Un-reinforced Masonry<br />

eg some older style office blocks<br />

Un-reinforced masonry infill has been known to fall off and often become<br />

displaced from its surrounding frames.<br />

• parapets and full walls fall off buildings due to inadequate anchors<br />

• multi-thickness walls may spilt and collapse or break at openings<br />

• mortar is often weak and made with too much lime content<br />

• mortar can also be made too strong, causing the masonry to fail<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 331

• walls that are more heavily loaded by roof and floors have been known to<br />

perform better than walls that are parallel to the framing, since the load of<br />

the floor tends to compress the bricks together thus increasing the " Bond "<br />

effect<br />

• roof / floors may collapse if there are no interior wall supports and if the<br />

earthquake has a long enough duration<br />

• voids are usually formed by wood floors in familiar patterns of "V", lean to and<br />

pancake formations<br />

• broken bricks often line the streets where these building are located and<br />

people can become trapped on the pavements or in their parked or passing<br />

vehicles.<br />

Concrete Tilt-up<br />

eg most new warehou<strong>ses</strong> with large floor areas<br />

• walls separate from wood floors/roof causing at least local collapse of the<br />

floor/roof, possible general collapse of walls and floor/roof<br />

• suspended wall panels become dislodged and fall off the building<br />

• walls may have short, weak columns between window openings that fail due<br />

to inadequate shear strength<br />

• large buildings that are "T" or "L", or other non-rectangular shape in design can<br />

have failures at their intersecting joints<br />

• if tilt up construction has been subjected to fire, extreme caution is required,<br />

as it has a tendency to collapse.<br />

Reinforced Concrete and Steel Construction<br />

eg most major new commercial buildings in town centres and cities<br />

• parapets and full walls fall off building due to inadequate anchors<br />

• multi-thickness walls may split and collapse or break at openings<br />

• mortar is often weak and made with too much lime content<br />

• walls that are more heavily loaded by roof and floors have been known to<br />

perform better than walls that are parallel to the framing, since the load of<br />

the floor tends to compress the bricks together thus increasing the " Bond "<br />

effect<br />

332 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

• roof / floors may collapse if there are no interior wall supports and if the<br />

earthquake has a long enough duration<br />

• voids are usually formed by wood floors in familiar patterns of "V", lean to and<br />

pancake formations<br />

• broken bricks often line the streets where these building are located and<br />

people can become trapped on the pavements or in their parked or passing<br />

vehicles.<br />

You can learn much about how a building is constructed from the Building Code of<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>.<br />

BUILDING<br />

CONSTRUCTION AND<br />

STRUCTURAL<br />

COLLAPSE<br />

The method of construction has a major impact<br />

on how a building might collapse, regardless of<br />

the cause of the collapse.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 333

Activity 1 Identifying structural collapse pattern<br />

Identify the construction of the building you are currently in (based on<br />

the seven classifications listed previously) and what possible collapse<br />

patterns could occur in the advent of structural collapse<br />

Question 1<br />

What is the construction of the building you are currently in?<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

Question 2<br />

What possible collapse patterns could occur in your building should a structural<br />

collapse occur?<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

......................................................................................................<br />

334 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Self Check<br />

Having completed this section, are you able to:<br />

Explain what is a scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment/reconnaissance<br />

Identify the types of information sought during a scene<br />

as<strong>ses</strong>sment/reconnaissance<br />

Understand what are Hot, Warm and Cold Zones<br />

Describe surface search procedures<br />

Describe and use Marking Systems including Victim Marking<br />

Identify different types of structural damage<br />

Identify different structural collapse patterns<br />

Recognise signs of secondary collapse<br />

If you have answered NO to any of these questions, ask your trainer for help.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 335

336 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Section 4.3 Casualty Handling<br />

Now that the initial scene as<strong>ses</strong>sment has been completed, you will have to start<br />

moving and managing casualties. Casualty management includes providing first<br />

aid, moving people to a safe place for further medical aid or to have their details<br />

recorded. How you move a casualty will depend on where they are and how they<br />

are injured.<br />

Before moving any casualty, you need to carefully as<strong>ses</strong>s their injuries using<br />

DRABCD, their condition and possible entrapment, ensuring they are not entrapped<br />

or tangled in some unseen object. You may need to carry casualties across piles of<br />

debris and uneven ground to safety. Some casualties may be seriously injured or<br />

unconscious.<br />

Although it is important to get people out quickly, you must remember that safety<br />

and proper handling will help prevent further injury.<br />

Moving casualties<br />

Rescues will be conducted under almost every conceivable adverse condition. The<br />

method used for casualty removal will depend on the location of the casualties.<br />

Casualties may need to be lowered from the upper floors of buildings, hoisted from<br />

below through holes in the floors, or removed by a combination of those<br />

techniques. Where casualties are handled by rescue personnel, care must be<br />

taken to ensure that further aggravation of injuries does not occur.<br />

All rescuers must be aware that the casualty is paramount even when immediate<br />

evacuation from a hazardous environment is necessary. A careful as<strong>ses</strong>sment<br />

must be made of the casualty’s injuries, condition and possible entrapment and<br />

a final check must be made to ensure that the casualty is actually ready to move<br />

and is not caught or entangled in some unseen object.<br />

RESCUERS MUST BE<br />

WELL TRAINED<br />

The importance of first aid <strong>training</strong> cannot be<br />

overstated.<br />

All rescuers must be trained to a reasonable<br />

qualification level of First Aid and Life Support<br />

in order to be able to handle casualties’ safely<br />

and effectively.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 337

After removal, many casualties will have to be carried over piles of debris and<br />

uneven ground before being handed over to the ambulance service or first aid<br />

station. Whilst speed of removal is important, it must be consistent with safety<br />

and proper handling to prevent further injury.<br />

The method used will depend on the immediate situation, the condition of<br />

casualties, type of injury and available equipment.<br />

The transportation of casualties over long distances is a very tiring task and<br />

requires fit personnel.<br />

There is a variety of techniques used for moving casualties using either single<br />

members or SES teams.<br />

Types of stretchers<br />

The three most commonly used categories of stretchers are:<br />

• folding or pole stretcher<br />

• basket stretcher<br />

• wrap around stretcher.<br />

Figure 7 Example of a folding stretcher<br />

Figure 8 Example of a basket stretcher<br />

338 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Figure 9 The Sked stretcher: an example of a wrap around stretcher<br />

Table 2 Advantages and Disadvantages of the three categories of stretchers<br />

Stretcher Advantages Disadvantages<br />

Folding • low cost<br />

• easily stored<br />

• light and portable.<br />

Basket<br />

Wrap around<br />

• strength and rigidity<br />

• ease of handling and rope<br />

attachment<br />

• ease of securing casualty.<br />

• conforms with body<br />

• ideal for confined spaces<br />

• ease of securing casualty.<br />

• lack of rigidity<br />

• poor spinal immobilisation<br />

• possibility of collapse during<br />

operations; difficulty in<br />

securing casualty.<br />

• awkward in confined<br />

spaces.<br />

• some styles do not<br />

provide full spinal<br />

immobilisation.<br />

Each SES Unit has access to stretchers. Talk to the person who is<br />

responsible for your <strong>training</strong> in your Unit and discuss which types are<br />

available at your Unit and their use.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 339

Extrication Devices and Backboards/Spineboards<br />

Extrication devices and backboards/spineboards assist when removing casualties<br />

from situations and maintaining spinal alignment. Backboards/spineboards provide<br />

a firm supportive surface and provide a safe method of moving casualties with<br />

suspected spinal damage by securing the casualty with straps and head restraints.<br />

Extrication devices are used in conjunction with backboards/spineboards and<br />

stretchers and are not patient transport devices. Extrication devices, when<br />

applied correctly, provide a higher level of spinal support.<br />

USE CORRECTLY<br />

Figure 10 Backboard/spineboard<br />

Figure 11 Extrication Device (Ferno KED)<br />

The importance of correct use of extrication<br />

devices and backboards/spineboards cannot be<br />

overstated when assisting casualties with<br />

suspected spinal damage.<br />

340 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

List<br />

Stretchers<br />

Improvised<br />

Stretchers<br />

Extrication<br />

Device<br />

Backboard/<br />

Spineboard<br />

Activity 2 Stretchers and extrication equipment<br />

Talk to your Trainer, identify and discuss the types of stretchers,<br />

extrication devices and backboards/spineboards your Unit has<br />

available. List the types available and the methods for their use.<br />

Types available and how to use<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 341

Classification of Casualties<br />

International practice - triage card tags<br />

Standard international practice is that the casualties are tagged with a triage card<br />

identifying them as<br />

RED TAG<br />

TOP PRIORITY<br />

ORANGE TAG<br />

2 ND PRIORITY<br />

GREEN TAG<br />

WALKING WOUNDED<br />

WHITE TAG<br />

Life threatening situation.<br />

• airway obstruction<br />

• breathing difficulties<br />

• chest pain (possible cardiac history).<br />

Serious but not yet life threatening<br />

• uncontrolled bleeding<br />

• major fractures.<br />

Needs to see a doctor but is not urgent<br />

• minor fractures<br />

• cuts that require stitches.<br />

Deceased<br />

(label with a no breathing and no pulse black<br />

border).<br />

342 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

NOTE<br />

Walking Injured<br />

Although the SES does not carry the<br />

tags, it is important for you to understand<br />

the tagging system when you are working<br />

with other agencies. This system provides<br />

a guideline for deciding in what order you<br />

are going to manage the casualties.<br />

The term, ‘Walking Injured’, is self-explanatory but the following are examples of<br />

some types of causalities who should not be allowed to walk if;<br />

• there is a marked degree of shock<br />

• there is the slightest risk of internal injuries<br />

• they have bled or are bleeding from an artery, even a small wound<br />

• they have head wounds even though they may appear to be slight.<br />

Slightly Injured Casualties<br />

These are casualties whose injuries require that they must be evacuated for<br />

further treatment, but the nature of the injury does not necessitate the use of a<br />

stretcher allowing evacuation to be effected by other means. Two examples of<br />

slightly-injured casualties are;<br />

• ca<strong>ses</strong> of serious shock<br />

• those with an injury to a lower limb unless it is only a slight flesh wound.<br />

Seriously Injured Casualties<br />

These are casualties who will require hospital treatment. A few examples of<br />

seriously-injured causalities are as follows;<br />

• all ca<strong>ses</strong> of internal haemorrhage; open wounds of the chest; shattered limbs,<br />

grossly lacerated and crushed limbs, wounds of the stomach, open<br />

complicated fractures of the skull, spine, pelvis and thigh, injuries involving<br />

the eye, injuries involving the lower jaw and control of the tongue<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 343

• ca<strong>ses</strong> in which further shock is likely to develop, as with persons trapped for<br />

long periods under debris or exposed to cold and wet, in fact all but those<br />

with trivial injuries or who are merely shaken, frightened or faint, not<br />

forgetting that very small external wounds may well be associated with<br />

damage beneath the surface<br />

• all diabetic patients who may be injured or who are suddenly taken ill.<br />

CAREFUL CASUALTY<br />

CHECKING<br />

Serious injuries will not always provide highly<br />

visible signs.<br />

Careful casualty checks must be carried out.<br />

The importance of first aid <strong>training</strong> cannot be<br />

over-emphasised!<br />

You may be required to treat and rescue casualties who are not seriously injured in<br />

order to reach more seriously injured persons. Where hazards present a risk to<br />

casualties being treated, follow the principle of ‘remove the casualty from the risk<br />

or remove the risk from the casualty’.<br />

Once you understand the basic principles of how to handle a casualty and what<br />

degree of injuries to expect, you can then look at the type of stretcher to use (if<br />

needed). Where possible, you should place seriously injured casualties on a<br />

stretcher. However, sometimes you may need to remove the casualty quickly or<br />

no stretchers are available. All single-rescuer techniques involve the risk of injury<br />

to the rescuer, so two-rescuer techniques are preferred.<br />

344 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Loading a stretcher<br />

Loading a stretcher is an important part of casualty handling. Using the correct<br />

methods is important for the safety and protection of both the casualty and the<br />

rescuers.<br />

CHECK CASUALTY IS<br />

FREE BEFORE LIFTING<br />

Four-rescuer method<br />

Make final checks by hand to ensure<br />

that a casualty is free of any<br />

entanglements or hooks before lifting.<br />

When four rescuers are loading a stretcher and where spinal injuries are not<br />

suspected you can use the following method:<br />

Make up the stretcher and place it near the casualty’s head or feet.<br />

• the team leader details three others to kneel on one side of the casualty, with<br />

the casualty lying flat on their back. Each rescuer kneels on the knee nearest<br />

the casualty’s feet, with the knee up that is clo<strong>ses</strong>t to the casualty’s head<br />

• the team leader kneels near the casualty’s hip on the opposite side to the<br />

three others and gently rolls the casualty towards themself<br />

• the other three place their hands and arms under the casualty and the team<br />

leader lowers the casualty back onto their arms. Make sure the casualty’s<br />

head is supported<br />

• the team leader gives the order: ‘Prepare to lift’<br />

• if no one shouts ‘Stop’, the team leader gives the order to ‘Lift’ and all four<br />

rescuers lift the casualty up<br />

• if necessary, the rescuers briefly support the casualty on their knees<br />

• the team leader then places the stretcher under the casualty<br />

• final orders are ‘Prepare to lower’, followed by ‘Lower’<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 345

• the three rescuers, helped by the team leader, lower the casualty on to the<br />

stretcher.<br />

Figure 12 Four rescuer lift<br />

Clothing lift (three rescuers)<br />

When the casualty’s injuries are not too severe but time is critical, or only three<br />

rescuers are available, you can use a clothing lift.<br />

Method<br />

• blanket a stretcher and place it close to the casualty<br />

• if the casualty is unconscious, tie their hands together with triangular bandage<br />

or similar materials<br />

• roll the casualty’s clothes together along the centre of the body. Make sure<br />

you support the head and neck of the casualty at all times<br />

• three rescuers are positioned on the opposite side of the casualty to the<br />

stretcher<br />

• normal commands are given and the casualty is gently placed on the<br />

stretcher.<br />

Figure 13 Clothing lift<br />

346 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Blanketing the stretcher<br />

Blanketing the stretcher:<br />

• makes the casualty more comfortable<br />

• keeps the casualty warm<br />

• helps to immobilise any fractures, that may have been sustained.<br />

You may need to use one or two blankets, depending on the weather and available<br />

blankets. You can use cotton bed sheets in very warm weather.<br />

Single-blanket method<br />

Lay one blanket diagonally across the stretcher with the corner of the blanket in<br />

the centre of the top of the stretcher. Leave about 150 mm overlapping. Place the<br />

casualty on the blanket so that their head is level with the top of the canvas. Fold<br />

over and tuck in the lower half of the blanket around the casualty’s feet and<br />

between their ankles to prevent chafing. Fold over the upper half of the blanket<br />

and tuck it in over the casualty.<br />

Figure 14 Single Blanket method<br />

Double-blanket method<br />

• lay a blanket lengthways across the stretcher, level with the head end. Have<br />

one quarter of the blanket extending over one side of the stretcher and one<br />

half on the other<br />

• place the second blanket with its centre in the middle of the stretcher and its<br />

end about 400mm from the top. Fold the sides into the centre and out at the<br />

foot<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 347

• place the casualty on the stretcher so their head is level with the top of the<br />

canvas<br />

• place the centre of the second blanket between the ankles of the casualty (to<br />

prevent chafing), then cross the end points of the blanket over their legs and<br />

tuck the points in. If possible, tuck these points between the knees and<br />

ankles to prevent chafing<br />

• take the short side of the first blanket over the body of the casualty and if<br />

possible, tuck it in<br />

• tuck the long side of the first blanket on the opposite side of the stretcher,<br />

and fold the blanket for head support (unless there is a spinal injury)<br />

• be sure to fold in the tips of the blanket so the casualty’s face is not covered.<br />

Figure 15 Double-blanket method<br />

If you are operating in a wet or contaminated area, it is advisable to concertina<br />

the ends of the first blanket down the sides of the stretcher before the second<br />

blanket is placed in position.<br />

Side position blanketing<br />

The blanket is used:<br />

• to provide warmth, comfort and immobilisation<br />

• as padding to keep the casualty in the side position.<br />

Method<br />

Roll the blanket end to end and position it on the stretcher. The rolled portion is<br />

used to pad the casualty’s back.<br />

Place a second blanket on the stretcher in a similar manner with the rolled portion<br />

on the opposite side. Fold the blanket over the casualty and tuck it under the first<br />

roll.<br />

348 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Blanketing a basket stretcher<br />

Basket stretchers are blanketed in the same way as folding stretchers.<br />

Alternatively, to maintain body heat, you may:<br />

• transfer the casualty into a sleeping bag in the stretcher, as long as you are<br />

still able to attend to injuries<br />

• lay two folded blankets under the casualty for insulation.<br />

Loading a stretcher is an important part of handling casualties. It is essential to<br />

use correct methods to:<br />

• ensure the wellbeing of the casualty<br />

• prevent aggravation of injuries.<br />

SECURE CASUALTIES<br />

It is important to ensure that casualties are<br />

secured in the stretcher at all times when<br />

moving over uneven ground.<br />

Do NOT secure casualties when moving over<br />

water.<br />

Casualty handling techniques using no equipment<br />

Single-rescuer human crutch<br />

For a single rescuer to function effectively as a human crutch, the casualty must<br />

be:<br />

• conscious<br />

• able to help the rescuer.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 349

Figure 16 Single rescuer human crutch<br />

With one hand, you should hold the casualty’s wrist over your shoulder and with<br />

the other hand, firmly grip the clothes at the waist or hip on the far side of the<br />

body. Keep the injured side of the casualty clo<strong>ses</strong>t to you.<br />

WARNING<br />

Pick-a-back carry (for a small person)<br />

All single rescuer techniques involve risk of<br />

injury for the rescuer. Rescuers need to take<br />

appropriate safety precautions to minimise<br />

risks.<br />

The pick-a-back carry is an effective method for smaller casualties. The casualty<br />

must be conscious. When they have been loaded, make sure they are supported<br />

well up on your hips with the body literally draped across your back.<br />

If the casualty is incorrectly positioned:<br />

• it will throw you off balance<br />

• the casualty is likely to fall<br />

• you are likely to hurt yourself or the casualty.<br />

If you use this method:<br />

• always consider the weight of the casualty<br />

• take appropriate safety precautions to make sure you don’t injure your back.<br />

350 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Figure 17 Pick-a-back carry<br />

WARNING<br />

Helping a casualty down a ladder<br />

Only use this technique if you are<br />

confident you can carry the weight of the<br />

casualty. Take appropriate safety<br />

precautions to minimise any risks of injury<br />

to both yourself and the casualty.<br />

Always take care when you are helping a person down a ladder, even if the person<br />

is conscious or uninjured. Many people are unused to heights and may freeze up or<br />

lose their hold.<br />

• approach the casualty on the ladder. Reassure and calm them before<br />

attempting the rescue. Keep talking to the casualty throughout the operation<br />

• take your position, one rung below the casualty, with arms around the<br />

casualty’s body and grasping the rungs<br />

• keep in step with the casualty, letting them set the pace<br />

• keep your knees close together. In this way you ensure support if the<br />

casualty lo<strong>ses</strong> hold or becomes unconscious<br />

• if the casualty becomes unconscious, let them slip down until their crotch<br />

rests on your knee<br />

• repeat this procedure for each step down the ladder. Then you can lower<br />

the casualty to the ground.<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 351

Figure 18 Help a casualty down a ladder<br />

DO NOT OVERLOAD<br />

THE LADDER<br />

Two-rescuer human crutch<br />

Do not overload the ladder.<br />

Check the safe working load before attempting<br />

this technique.<br />

The maximum load rating for portable ladders<br />

is specified as 120kg, and this must be<br />

considered in the operational use of ladders.<br />

However it pays to check the manufacturers’<br />

specifications as some ladders may differ<br />

depending on the manufacturer. This is<br />

generally indicated on the side of a ladder.<br />

The two-rescuer human crutch is similar to the one rescuer human crutch, except<br />

that the casualty is supported on both sides.<br />

Method<br />

Cross the arms of the rescuers over the casualty’s back and grasp the clothing on<br />

the opposite sides of the body.<br />

Figure 19 Two rescuer human crutch<br />

352 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Two-handed seat<br />

Use the two-handed seat to deal with a casualty who has to be carried.<br />

Method<br />

Two rescuers kneel on either side of the casualty and get them into a sitting<br />

position. Both rescuers place an arm under the casualty’s knee and link up with<br />

the hand to wrist grip. The rescuers cross their free arms over the casualty’s back,<br />

where they get a firm grip on the clothing. The team leader gives the normal<br />

orders for lifting and lowering.<br />

Figure 20 Two handed seat<br />

Three-handed seat<br />

Use the three-handed seat to give the casualty good support while being<br />

reasonably comfortable for the rescuers. This method has the added advantage<br />

that one rescuer has a spare hand. The casualty must be conscious as neither<br />

rescuer can support their back.<br />

Method<br />

One rescuer grasps their left wrist with their right hand. The second rescuer<br />

places their hand and wrist to form a seat. If the casualty is capable of standing<br />

for a short period, place the seat under the buttocks. If not, the rescuers must<br />

first place their hands under the casualty’s knees then join up.<br />

Figure 21 Three handed seat<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 353

Four-handed seat<br />

This method provides a comfortable seat for the casualty and places a minimum<br />

strain on the rescuers. However, as shown in the figure below, the casualty must<br />

be conscious and able to hold on.<br />

Method<br />

In the four-handed seat method, each rescuer grasps their own left wrist and the<br />

hands are joined up.<br />

Figure 22 Four handed seat<br />

Fore and aft lift and carry<br />

This method is suitable when two rescuers are handling an unconscious casualty.<br />

In the fore and aft method, the casualty’s wrists are tied together.<br />

Method<br />

The first rescuer stoops at the rear of the casualty. The first rescuer then reaches<br />

under the casualty’s arms and grips the casualty’s wrists. The second rescuer<br />

stoops between the casualty’s legs, grasping them underneath the knees. The<br />

standard lift orders are given and the casualty is lifted to the carrying position.<br />

The advantage of this method is that the rescuer supporting the casualty’s feet can<br />

have a free hand, which can be used to open doors, clear debris, etc.<br />

354 © Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1)

Figure 23 Fore and aft lift/carry<br />

Figure 24 Fore and aft lift/carry<br />

KEEP AIRWAYS OPEN<br />

WHEN CARRYING<br />

UNCONSCIOUS<br />

CASUALTY<br />

An unconscious casualty should always be<br />

carried in the recovery position and/or in a<br />

position which ensures that their airway is open<br />

and protected.<br />

Mixed teams and special stretcher combinations<br />

Blanket-lift method (four or six rescuers)<br />

The blanket lift is an effective way to load a casualty onto a stretcher or move a<br />

casualty in a confined space.<br />

Method<br />

• prepare a stretcher using one blanket only<br />

• roll a blanket lengthwise to the centre line and lay the rolled section along<br />

the side of the casualty (casualty flat on back)<br />

• the team leader is at the casualty’s head or left shoulder<br />

• the team leader directs two (or three) rescuers to kneel on each side of the<br />

casualty. The rescuers on one side ea<strong>ses</strong> the casualty away from them and<br />

pushes the rolled section of the blanket well under the casualty<br />

© Commonwealth of <strong>Australia</strong> (Version 1) 355

• with the rolled-up section of the blanket now under the centre of the<br />