The Language of Poetry - LanguageArts-NHS

The Language of Poetry - LanguageArts-NHS

The Language of Poetry - LanguageArts-NHS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

unit 7<br />

Literary<br />

Analysis<br />

Workshop<br />

Characteristics<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Poetry</strong><br />

Emily Dickinson once wrote, “If I feel physically as if the top <strong>of</strong> my head were taken<br />

<strong>of</strong>f, I know that is poetry.” A good poem can make readers look at the world in a new<br />

way. A simple fork becomes the foot <strong>of</strong> a strange and unearthly bird; death itself<br />

appears as the driver <strong>of</strong> a carriage. After reading a poem, you might find yourself<br />

repeating lines in your mind or remembering images that “spoke” to you from the<br />

page. What gives poetry such power? Read a poem closely, and you’ll see how it has<br />

been carefully crafted to affect you.<br />

Part 1: Form<br />

What you’ll most likely notice first about a poem is its form, or the distinctive<br />

way the words are arranged on the page. Form refers to the length and<br />

placement <strong>of</strong> lines and the way they are grouped into stanzas. Similar to<br />

a paragraph in narrative writing, each stanza conveys a unified idea and<br />

contributes to a poem’s overall meaning.<br />

Poems can be traditional or organic in form. Regardless <strong>of</strong> its structure,<br />

though, a poem’s form is <strong>of</strong>ten deliberately chosen to echo its meaning.<br />

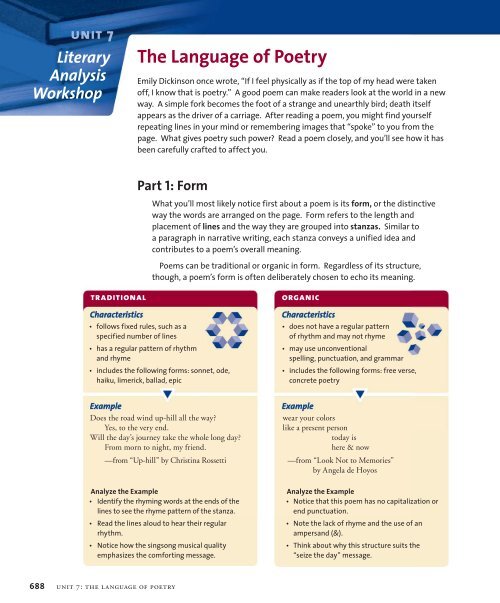

traditional organic<br />

• follows fixed rules, such as a<br />

specified number <strong>of</strong> lines<br />

• has a regular pattern <strong>of</strong> rhythm<br />

and rhyme<br />

• includes the following forms: sonnet, ode,<br />

haiku, limerick, ballad, epic<br />

Example<br />

Does the road wind up-hill all the way?<br />

Yes, to the very end.<br />

Will the day’s journey take the whole long day?<br />

From morn to night, my friend.<br />

—from “Up-hill” by Christina Rossetti<br />

Analyze the Example<br />

• Identify the rhyming words at the ends <strong>of</strong> the<br />

lines to see the rhyme pattern <strong>of</strong> the stanza.<br />

• Read the lines aloud to hear their regular<br />

rhythm.<br />

• Notice how the singsong musical quality<br />

emphasizes the comforting message.<br />

688 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

Characteristics<br />

• does not have a regular pattern<br />

<strong>of</strong> rhythm and may not rhyme<br />

• may use unconventional<br />

spelling, punctuation, and grammar<br />

• includes the following forms: free verse,<br />

concrete poetry<br />

Example<br />

wear your colors<br />

like a present person<br />

today is<br />

here & now<br />

—from “Look Not to Memories”<br />

by Angela de Hoyos<br />

Analyze the Example<br />

• Notice that this poem has no capitalization or<br />

end punctuation.<br />

• Note the lack <strong>of</strong> rhyme and the use <strong>of</strong> an<br />

ampersand (&).<br />

• Think about why this structure suits the<br />

“seize the day” message.

model 1: traditional form<br />

<strong>The</strong> following two stanzas are from an ode, a complex lyric poem that<br />

addresses a serious theme, such as justice, truth, or the passage <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

While odes can follow just about any structure, “<strong>The</strong> Fire <strong>of</strong> Driftwood”<br />

is traditional in form because <strong>of</strong> its regular stanzas, rhythm, and rhyme.<br />

Here, the speaker—the voice that talks to the reader—sadly reflects on<br />

how he and his friends have grown apart.<br />

from the fire <strong>of</strong> driftwood<br />

Poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow<br />

5<br />

We spake <strong>of</strong> many a vanished scene,<br />

Of what we once had thought and said,<br />

Of what had been, and might have been,<br />

And who was changed, and who was dead;<br />

And all that fills the hearts <strong>of</strong> friends,<br />

When first they feel, with secret pain,<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir lives thenceforth have separate ends,<br />

And never can be one again.<br />

model 2: organic form<br />

This poem is written in free verse, with no regular pattern <strong>of</strong> rhythm<br />

and rhyme. Notice how its form differs from that <strong>of</strong> Longfellow’s poem.<br />

i am not done yet<br />

Poem by Lucille Clifton<br />

5<br />

10<br />

as possible as yeast<br />

as imminent as bread<br />

a collection <strong>of</strong> safe habits<br />

a collection <strong>of</strong> cares<br />

less certain than i seem<br />

more certain than i was<br />

a changed changer<br />

i continue to continue<br />

where i have been<br />

most <strong>of</strong> my lives is<br />

where i’m going<br />

Close Read<br />

1. How is the form <strong>of</strong> the<br />

first stanza similar to<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the second?<br />

Consider the number and<br />

length <strong>of</strong> the lines, the<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> the rhyme,<br />

and the rhythm.<br />

2. Summarize the different<br />

ideas expressed in each<br />

stanza.<br />

Close Read<br />

1. Using the chart on the<br />

preceding page, identify<br />

two characteristics that<br />

make this poem organic<br />

in form.<br />

2. Read the poem aloud.<br />

<strong>The</strong> short lines and<br />

the rhythm help to<br />

emphasize the ideas<br />

expressed in each line.<br />

Choose two lines and<br />

explain what the speaker<br />

is saying.<br />

literary analysis workshop 689

Part 2: Poetic Elements<br />

What gives one poem a brisk rhythm and another the sound <strong>of</strong> an everyday<br />

conversation? How can two poems on the same subject—for example, the<br />

simplicity <strong>of</strong> nature—create dramatically different images in your mind? Sound<br />

devices and imagery are the techniques that give dimension to words on a page.<br />

sound devices<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> the power <strong>of</strong> poetry depends on rhythm—the pattern <strong>of</strong> stressed and<br />

unstressed syllables in each line. Poets use rhythm to emphasize important<br />

words or ideas and to create a mood that suits their subject. Some poems have<br />

a regular pattern <strong>of</strong> rhythm, which is called meter. Analyzing the effects <strong>of</strong> a<br />

poem’s rhythm begins with scanning, or marking, the meter. Unstressed syllables<br />

are marked with a ( ) and stressed syllables with a ( ) , as in these lines from<br />

“A Dirge” by Percy Bysshe Shelley:<br />

Rough wind, / that moan / est loud a<br />

Grief / too sad / for song; b<br />

Wild wind / when sul / len cloud a<br />

Knells / all the night / long. b<br />

A regular pattern <strong>of</strong> rhyme is called a rhyme scheme. Rhyme scheme is charted by<br />

assigning a letter <strong>of</strong> the alphabet to matching end rhymes, as shown in “A Dirge.”<br />

Poets also use many other sound devices to create specific effects. In each <strong>of</strong><br />

the following examples, notice how the device helps to establish a mood, create<br />

a rhythm, and suggest different sounds and sights <strong>of</strong> the sea.<br />

repetition<br />

a sound, word, phrase, or line that is repeated for emphasis<br />

and unity<br />

Break, break, break,<br />

On thy cold gray stones, O Sea!<br />

— from “Break, Break, Break” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson<br />

assonance<br />

the repetition <strong>of</strong> vowel sounds in words that do not end<br />

with the same consonant<br />

<strong>The</strong> waves break fold on jewelled fold.<br />

—from “Moonlight” by Sara Teasdale<br />

690 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

alliteration<br />

the repetition <strong>of</strong> consonant sounds at the beginnings<br />

<strong>of</strong> words<br />

<strong>The</strong> scraggy rock spit shielding the town’s blue bay<br />

—from “Departure” by Sylvia Plath<br />

consonance<br />

the repetition <strong>of</strong> consonant sounds within and at the ends<br />

<strong>of</strong> words<br />

And black are the waters that sparkled so green.<br />

—from “Seal Lullaby” by Rudyard Kipling

model 1: rhythm and rhyme<br />

<strong>The</strong> speakers in this next poem could be understood to be the collective<br />

voice <strong>of</strong> the pool players mentioned underneath the title. Read the poem<br />

aloud to hear its unique rhyme scheme and rhythm. In what ways do<br />

these elements reflect the fast-lane lifestyle that the speakers describe?<br />

We Real C l<br />

<strong>The</strong> Pool Players.<br />

Seven at <strong>The</strong> Golden Shovel.<br />

5<br />

model 2: other sound devices<br />

This poem immerses you in the edge-<strong>of</strong>-your-seat excitement <strong>of</strong> a close<br />

baseball game. What sound devices has the poet used to create this effect?<br />

5<br />

10<br />

We real cool. We<br />

Left school. We<br />

Lurk late. We<br />

Strike straight. We<br />

Sing sin. We<br />

Thin gin. We<br />

Jazz June. We<br />

Die soon.<br />

Poised between going on and back, pulled<br />

Both ways taut like a tightrope-walker,<br />

Fingertips pointing the opposites,<br />

Now bouncing tiptoe like a dropped ball<br />

Or a kid skipping rope, come on, come on,<br />

Running a scattering <strong>of</strong> steps sidewise,<br />

How he teeters, skitters, tingles, teases,<br />

Taunts them, hovers like an ecstatic bird,<br />

He’s only flirting, crowd him, crowd him,<br />

Delicate, delicate, delicate, delicate—now!<br />

<br />

Poem by Gwendolyn Brooks<br />

Poem by Robert Francis<br />

Literary Analysis Workshop<br />

Close Read<br />

1. Even though the rhyming<br />

words in this poem<br />

fall in the middle <strong>of</strong><br />

the lines, they sound<br />

like end rhymes. If you<br />

treat these words as<br />

end rhymes, what is the<br />

rhyme scheme?<br />

2. One way to read this<br />

poem is to stress every<br />

syllable. How would you<br />

describe the rhythm?<br />

Explain how it echoes<br />

the speakers’ attitude<br />

toward life.<br />

Close Read<br />

1. Read the boxed text<br />

aloud. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong><br />

alliteration emphasizes<br />

the tension that the base<br />

stealer feels. Find another<br />

example <strong>of</strong> alliteration<br />

and explain its effect.<br />

2. Identify two other sound<br />

devices that the poet uses<br />

and describe their effects.<br />

literary analysis workshop<br />

691

imagery and figurative language<br />

I can remember wind-swept streets <strong>of</strong> cities<br />

on cold and blustery nights, on rainy days;<br />

heads under shabby felts and parasols<br />

and shoulders hunched against a sharp concern.<br />

—from “Memory” by Margaret Walker<br />

Do these lines make you want to stay indoors, nestled under layers <strong>of</strong> blankets? If<br />

so, the reason is imagery, or words and phrases that re-create sensory experiences<br />

for readers. Through the highlighted images, the poet helps readers visualize the<br />

bleak scene—the way it looks, sounds, and even feels—in striking detail.<br />

One way poets create strong imagery is through the use <strong>of</strong> figurative<br />

language, which conveys meanings beyond the literal meanings <strong>of</strong> words.<br />

Figurative language pops up all the time in everyday speech. For example, if<br />

you say “My heart sank when I heard the disappointing news,” your friends<br />

will understand that your heart did not literally sink. Through this figurative<br />

expression, you are conveying the emotional depth <strong>of</strong> your disappointment.<br />

In the following examples, notice what each technique helps to emphasize<br />

about the subject described.<br />

figurative language<br />

simile<br />

a comparison between two<br />

unlike things using the words<br />

like, as, or as if<br />

metaphor<br />

a comparison between two<br />

unlike things but without the<br />

words like or as<br />

personification<br />

a description <strong>of</strong> an object, an<br />

animal, a place, or an idea in<br />

human terms<br />

hyperbole<br />

an exaggeration for emphasis<br />

or humorous effect<br />

692 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

example<br />

I remember how you sang in your stone shoes<br />

light-voiced as dusk or feathers.<br />

—from “Elegy for My Father” by Robert Winner<br />

<strong>The</strong> door <strong>of</strong> winter<br />

is frozen shut.<br />

—from “Wind Chill” by Linda Pastan<br />

Death, be not proud, though some have<br />

callèd thee<br />

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so.<br />

—from “Sonnet 10” by John Donne<br />

Here once the embattled farmers stood<br />

And fired the shot heard round the world.<br />

—from “<strong>The</strong> Concord Hymn”<br />

by Ralph Waldo Emerson

model 3: imagery<br />

Notice the imagery this poet uses to transport you to the hot sands <strong>of</strong> an<br />

island in the West Indies.<br />

Midsummer, Tobago<br />

5<br />

10<br />

Broad sun-stoned beaches.<br />

White heat.<br />

A green river.<br />

A bridge,<br />

scorched yellow palms<br />

from the summer-sleeping house<br />

drowsing through August.<br />

Days I have held,<br />

days I have lost,<br />

days that outgrow, like daughters,<br />

my harbouring arms.<br />

model 4: figurative language<br />

Poem by Derek Walcott<br />

<strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> figurative language in this poem strengthens the contrast<br />

between a lifeless winter day and the vibrancy <strong>of</strong> the horses.<br />

from<br />

Horses<br />

Poem by Pablo Neruda, translated by Alastair Reid<br />

Text not available for electronic use.<br />

Please refer to the text in the textbook.<br />

Literary Analysis Workshop<br />

Close Read<br />

1. <strong>The</strong> boxed image<br />

appeals to the senses <strong>of</strong><br />

sight and touch. Identify<br />

three other images and<br />

describe the scene they<br />

conjure up in your mind.<br />

2. How does the speaker<br />

feel about the summer<br />

days he or she describes?<br />

Explain how the image in<br />

lines 10–11 helps you to<br />

understand the speaker’s<br />

emotions.<br />

Close Read<br />

1. One example <strong>of</strong> a simile<br />

is boxed. What does<br />

this comparison tell<br />

you about the air? Find<br />

another simile and<br />

explain the comparison.<br />

2. In line 5, the poet uses<br />

personification to<br />

describe winter. What<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> winter<br />

does this comparison<br />

emphasize?<br />

literary analysis workshop 693

Part 3: Analyze the Literature<br />

Apply what you have just learned about the forms, techniques, and effects <strong>of</strong><br />

poetry by comparing the next two poems. <strong>The</strong> first describes the dead-end life<br />

<strong>of</strong> Flick Webb, a former high school basketball star. Read the poem a first time,<br />

looking for details that help you to understand the character <strong>of</strong> Flick. <strong>The</strong>n read<br />

the poem aloud to get the full impact.<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

25<br />

30<br />

ex-Basketball Player<br />

Poem by John Updike<br />

Pearl Avenue runs past the high-school lot,<br />

Bends with the trolley tracks, and stops, cut <strong>of</strong>f<br />

Before it has a chance to go two blocks,<br />

At Colonel McComsky Plaza. Berth’s Garage<br />

Is on the corner facing west, and there,<br />

Most days, you’ll find Flick Webb, who helps Berth out.<br />

Flick stands tall among the idiot pumps—<br />

Five on a side, the old bubble-head style,<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir rubber elbows hanging loose and low.<br />

One’s nostrils are two S’s, and his eyes<br />

An E and O. And one is squat, without<br />

A head at all—more <strong>of</strong> a football type.<br />

Once Flick played for the high-school team, the Wizards.<br />

He was good: in fact, the best. In ’46<br />

He bucketed three hundred ninety points,<br />

A county record still. <strong>The</strong> ball loved Flick.<br />

I saw him rack up thirty-eight or forty<br />

In one home game. His hands were like wild birds.<br />

He never learned a trade, he just sells gas,<br />

Checks oil, and changes flats. Once in a while,<br />

As a gag, he dribbles an inner tube,<br />

But most <strong>of</strong> us remember anyway.<br />

His hands are fine and nervous on the lug wrench.<br />

It makes no difference to the lug wrench, though.<br />

Off work, he hangs around Mae’s Luncheonette.<br />

Grease-gray and kind <strong>of</strong> coiled, he plays pinball,<br />

Smokes those thin cigars, nurses lemon phosphates.<br />

Flick seldom says a word to Mae, just nods<br />

Beyond her face toward bright applauding tiers<br />

Of Necco Wafers, Nibs, and Juju Beads.<br />

694 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

Close Read<br />

1. In the second stanza, Flick<br />

stands next to gas pumps,<br />

which are personified as<br />

athletes. Citing details in<br />

the stanza, describe this<br />

image as you see it in your<br />

mind’s eye.<br />

2. Identify the simile in the<br />

third stanza. What does<br />

it tell you about Flick’s<br />

athletic ability in high<br />

school?<br />

3. Now that you know more<br />

about the character <strong>of</strong><br />

Flick, reread lines 1–3.<br />

How does the image <strong>of</strong><br />

Pearl Avenue remind you<br />

<strong>of</strong> him?<br />

4. <strong>The</strong> poet uses alliteration<br />

in the last stanza. One<br />

example is boxed. Find<br />

two more examples.

<strong>The</strong> description <strong>of</strong> basketball players in this poem provides a sharp contrast to<br />

the sad portrait <strong>of</strong> Flick Webb in “Ex-Basketball Player.”<br />

SLAM,<br />

&<br />

DUNK,<br />

HOOK<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

25<br />

30<br />

35<br />

40<br />

Poem by Yusef Komunyakaa<br />

Fast breaks. Lay ups. With Mercury’s<br />

Insignia on our sneakers,<br />

We outmaneuvered to footwork<br />

Of bad angels. Nothing but a hot<br />

Swish <strong>of</strong> strings like silk<br />

Ten feet out. In the roundhouse<br />

Labyrinth our bodies<br />

Created, we could almost<br />

Last forever, poised in midair<br />

Like storybook sea monsters.<br />

A high note hung there<br />

A long second. Off<br />

<strong>The</strong> rim. We’d corkscrew<br />

Up & dunk balls that exploded<br />

<strong>The</strong> skullcap <strong>of</strong> hope & good<br />

Intention. Lanky, all hands<br />

& feet . . . sprung rhythm.<br />

We were metaphysical when girls<br />

Cheered on the sidelines.<br />

Tangled up in a falling,<br />

Muscles were a bright motor<br />

Double-flashing to the metal hoop<br />

Nailed to our oak.<br />

When Sonny Boy’s mama died<br />

He played nonstop all day, so hard<br />

Our backboard splintered.<br />

Glistening with sweat,<br />

We rolled the ball <strong>of</strong>f<br />

Our fingertips. Trouble<br />

Was there slapping a blackjack<br />

Against an open palm.<br />

Dribble, drive to the inside,<br />

& glide like a sparrow hawk.<br />

Lay ups. Fast breaks.<br />

We had moves we didn’t know<br />

We had. Our bodies spun<br />

On swivels <strong>of</strong> bone & faith,<br />

Through a lyric slipknot<br />

Of joy, & we knew we were<br />

Beautiful & dangerous.<br />

Literary Analysis Workshop<br />

Close Read<br />

1. Is the form <strong>of</strong> this poem<br />

traditional or organic?<br />

Support your answer<br />

with specific examples.<br />

2. Read the boxed lines<br />

aloud and identify two<br />

sound devices that are<br />

used. What does the<br />

rhythm in these lines<br />

remind you <strong>of</strong>?<br />

3. <strong>The</strong> speaker describes<br />

the players as “Beautiful<br />

& dangerous” in line 40.<br />

Find two examples <strong>of</strong><br />

figurative language that<br />

suggest either <strong>of</strong> these<br />

qualities. Explain your<br />

choices.<br />

4. Contrast the two poems,<br />

citing three differences.<br />

Think about each poet’s<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> the subject,<br />

as well as his use <strong>of</strong><br />

poetic techniques.<br />

literary analysis workshop 695

696<br />

Before Reading<br />

<strong>The</strong>re Will Come S<strong>of</strong>t Rains<br />

Poem by Sara Teasdale<br />

Meeting at Night<br />

Poem by Robert Browning<br />

<strong>The</strong> Sound <strong>of</strong> Night<br />

Poem by Maxine Kumin<br />

What is our place in nature?<br />

KEY IDEA Are humans more powerful than nature? Think <strong>of</strong> how we<br />

change landscapes, drive other species to extinction, and otherwise<br />

use nature for our own ends. Or are humans insignificant in the face<br />

<strong>of</strong> nature’s power?<br />

DISCUSS Think about a recent encounter you had with nature. What<br />

attitude did you express—admiration? indifference? In a small<br />

group, discuss your overall attitudes toward nature.

literary analysis: sound devices<br />

One common sound device used in poetry is rhyme, the<br />

repetition <strong>of</strong> sounds at the ends <strong>of</strong> words. End rhyme is<br />

rhyme at the ends <strong>of</strong> lines, as in this excerpt:<br />

Whose woods these are I think I know.<br />

His house is in the village though.<br />

Another sound device is alliteration, the repetition <strong>of</strong><br />

consonant sounds at the beginnings <strong>of</strong> words, as in Droning<br />

a drowsy syncopated tune.<br />

Still another sound device is onomatopoeia, the use <strong>of</strong><br />

words that imitate sounds, as in <strong>The</strong> buzz saw snarled and<br />

rattled in the yard. As you read the following poems about<br />

nature, notice their sound devices. Record examples on a chart.<br />

Title<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re Will<br />

Come S<strong>of</strong>t<br />

Rains”<br />

End Rhyme<br />

ground / sound<br />

(lines 1 and 2)<br />

reading strategy: reading poetry<br />

Alliteration Onomatopoeia<br />

Reading poetry requires paying attention not only to the<br />

meaning <strong>of</strong> the words but to the way they look and sound.<br />

<strong>The</strong> following strategies will help you.<br />

• Notice how the lines are arranged on the page. Are they<br />

long lines, or short? Are they grouped into regular stanzas or<br />

irregular stanzas, or are they not divided into stanzas at all?<br />

Stanza breaks usually signal the start <strong>of</strong> a new idea.<br />

• Pause in your reading where punctuation marks appear,<br />

just as you would when reading prose. Note that in poetry,<br />

punctuation does not always occur at the end <strong>of</strong> a line; a<br />

thought may continue for several lines.<br />

• Read a poem aloud several times. As you read, notice whether<br />

the rhythm is regular or varied. Is there a rhyme scheme, or<br />

regular pattern <strong>of</strong> end rhyme? For example, you’ll notice that<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re Will Come S<strong>of</strong>t Rains” is written in couplets, two-line<br />

units with an aa rhyme scheme. Regular patterns <strong>of</strong> rhythm<br />

and rhyme give a musical quality to poems.<br />

Review: Make Inferences<br />

Sara Teasdale: Love<br />

and War Sara Teasdale<br />

explored the topic <strong>of</strong><br />

love in all <strong>of</strong> its aspects.<br />

Drawing on her own<br />

experiences, she wrote<br />

about the beauty,<br />

pleasure, fragility, and<br />

heartache <strong>of</strong> love in<br />

exquisitely crafted lyric<br />

poems. In reaction to<br />

World War I, she also<br />

wrote antiwar poems,<br />

such as “<strong>The</strong>re Will<br />

Come S<strong>of</strong>t Rains.”<br />

Robert Browning:<br />

Painter <strong>of</strong> Portraits<br />

Robert Browning was<br />

a master at capturing<br />

psychological<br />

complexity. Using the<br />

dramatic monologue,<br />

a poem addressed<br />

to a silent listener,<br />

he conveyed the<br />

personalities <strong>of</strong> both<br />

fictional and historical<br />

figures. “Meeting at<br />

Night” is one <strong>of</strong> his<br />

shorter lyric poems.<br />

Maxine Kumin: Poet<br />

<strong>of</strong> Place <strong>The</strong> poetry<br />

<strong>of</strong> Maxine Kumin<br />

is rooted in New<br />

England rural life.<br />

Using traditional verse<br />

forms, Kumin explores<br />

changes in nature,<br />

people’s relationship<br />

to the land and its<br />

creatures, and human<br />

mortality, loss, and<br />

survival.<br />

Sara Teasdale<br />

1884–1933<br />

Robert Browning<br />

1812–1889<br />

Maxine Kumin<br />

born 1925<br />

more about the author<br />

For more on these poets, visit the<br />

Literature Center at ClassZone.com.<br />

697

<strong>The</strong>re Will Come<br />

S<strong>of</strong>t Rains<br />

Sara Teasdale<br />

5<br />

10<br />

<strong>The</strong>re will come s<strong>of</strong>t rains and the smell <strong>of</strong> the ground,<br />

And swallows circling with their shimmering sound; a<br />

And frogs in the pools singing at night,<br />

And wild plum-trees in tremulous white;<br />

Robins will wear their feathery fire<br />

Whistling their whims on a low fence-wire; b<br />

And not one will know <strong>of</strong> the war, not one<br />

Will care at last when it is done.<br />

Not one would mind, neither bird nor tree<br />

If mankind perished utterly;<br />

And Spring herself, when she woke at dawn,<br />

Would scarcely know that we were gone.<br />

698 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

a READING POETRY<br />

Read the first stanza<br />

aloud. Notice that it is a<br />

rhymed couplet. What<br />

expectations are set up<br />

by this end rhyme?<br />

b SOUND DEVICES<br />

What examples <strong>of</strong><br />

alliteration can you<br />

identify in lines 1–6?<br />

ANALYZE VISUALS<br />

What overall feeling<br />

do you get from this<br />

landscape?<br />

Spring Landscape (1909),<br />

Constant Permeke. Constant<br />

Permeke Museum, Jabbeke, Belgium.<br />

© 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS),<br />

New York/SABAM, Brussels.

Meeting at Night<br />

Robert Browning<br />

700 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

5<br />

10<br />

1<br />

<strong>The</strong> gray sea and the long black land;<br />

And the yellow half-moon large and low;<br />

And the startled little waves that leap<br />

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,<br />

As I gain the cove 1 with pushing prow, 2<br />

And quench its speed i’ the slushy sand. c<br />

2<br />

<strong>The</strong>n a mile <strong>of</strong> warm sea-scented beach;<br />

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;<br />

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch<br />

And blue spurt <strong>of</strong> a lighted match,<br />

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,<br />

Than the two hearts beating each to each! d<br />

1. cove: a small, partly enclosed body <strong>of</strong> water.<br />

2. prow (prou): the front part <strong>of</strong> a boat.<br />

Moonrise (1906), Guillermo<br />

Gomez y Gil. Oil on canvas. Musée<br />

des Beaux-Arts, Pau, France. Photo<br />

© Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library.<br />

c READING POETRY<br />

Read the first stanza<br />

aloud. What rhyme<br />

scheme do you notice?<br />

d MAKE INFERENCES<br />

Where does the speaker<br />

arrive, and what happens<br />

once he is there?

<strong>The</strong> Sound<br />

<strong>of</strong> Night<br />

Maxine Kumin<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

25<br />

And now the dark comes on, all full <strong>of</strong> chitter noise.<br />

Birds huggermugger 1 crowd the trees,<br />

the air thick with their vesper 2 cries,<br />

and bats, snub seven-pointed kites,<br />

skitter across the lake, swing out,<br />

squeak, chirp, dip, and skim on skates<br />

<strong>of</strong> air, and the fat frogs wake and prink<br />

wide-lipped, noisy as ducks, drunk<br />

on the boozy black, gloating chink-chunk. e<br />

And now on the narrow beach we defend ourselves from dark.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cooking done, we build our firework<br />

bright and hot and less for outlook<br />

than for magic, and lie in our blankets<br />

while night nickers around us. Crickets<br />

chorus hallelujahs; paws, quiet<br />

and quick as raindrops, play on the stones<br />

expertly s<strong>of</strong>t, run past and are gone;<br />

fish pulse in the lake; the frogs hoarsen.<br />

Now every voice <strong>of</strong> the hour—the known, the supposed, the strange,<br />

the mindless, the witted, the never seen—<br />

sing, thrum, impinge, 3 and rearrange<br />

endlessly; and debarred 4 from sleep we wait<br />

for the birds, importantly silent,<br />

for the crease <strong>of</strong> first eye-licking light,<br />

for the sun, lost long ago and sweet.<br />

By the lake, locked black away and tight,<br />

we lie, day creatures, overhearing night.<br />

1. huggermugger: disorderly.<br />

2. vesper: pertaining to the evening; a type <strong>of</strong> swallow that sings in the evening.<br />

3. impinge (Gm-pGnjP): to strike or push upon.<br />

4. debarred: prevented or hindered.<br />

Trees at Night (c. 1900), Thomas Meteyard. Berry Hill Gallery, New<br />

York. Photo © Edward Owen/Art Resource, New York.<br />

e SOUND DEVICES<br />

What examples <strong>of</strong><br />

onomatopoeia can<br />

you identify in the first<br />

stanza? What do they<br />

add to the poem?<br />

meeting at night / the sound <strong>of</strong> night 701

After Reading<br />

Comprehension<br />

1. Clarify According to the speaker in Teasdale’s poem, how would the natural<br />

world react if “mankind perished utterly”?<br />

2. Clarify Whom does the speaker in Browning’s poem meet when he arrives at<br />

his destination?<br />

3. Clarify What time and place are described in Kumin’s poem?<br />

Literary Analysis<br />

4. Reading <strong>Poetry</strong> Which poem did you appreciate most when read aloud?<br />

Explain the qualities that were brought out in an oral reading.<br />

5. Analyze Rhyme Describe how end rhyme is used in each poem. Which<br />

poems employ a regular rhyme scheme? What ideas are emphasized through<br />

end rhyme? Use a chart like the one shown to plan your answer.<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re Will Come S<strong>of</strong>t Rains”<br />

“Meeting at Night”<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Sound <strong>of</strong> Night”<br />

6. Recognize Alliteration Which poem makes the most obvious use <strong>of</strong><br />

alliteration? What feelings or ideas are suggested by these repeated<br />

consonant sounds?<br />

7. Relate <strong>The</strong>me and Sound Devices Describe the qualities <strong>of</strong> nature conveyed<br />

in each poem. How are sound devices used to suggest these qualities? Refer<br />

to your sound devices chart to plan your answer.<br />

8. Draw Conclusions What does each poem suggest about humans and nature?<br />

Literary Criticism<br />

Rhyme Important<br />

Scheme Rhyming Words<br />

9. Critical Interpretations According to one critic, Teasdale’s poetry “expresses<br />

the fragility <strong>of</strong> human life where the only real certainty comes from nature.”<br />

How does this comment apply to “<strong>The</strong>re Will Come S<strong>of</strong>t Rains”?<br />

702 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry

Reading-Writing Connection<br />

Broaden your understanding <strong>of</strong> the poems by responding to these prompts.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n use Revision: Grammar and Style to improve your writing.<br />

writing prompts self-check<br />

A. Short Response: Support an Opinion<br />

Which <strong>of</strong> the three poems expresses the greatest<br />

appreciation <strong>of</strong> nature? Defend your choice in one or<br />

two paragraphs, using examples from the poems.<br />

B. Extended Response: Interpret <strong>The</strong>me<br />

What is the theme or message <strong>of</strong> each poem that you<br />

read? Drawing on details from the poems, write a<br />

three-to-five-paragraph response.<br />

revision: grammar and style<br />

USE PRECISE LANGUAGE It is important for writers to choose words that<br />

effectively express the rhythm, sound, and imagery they wish to convey to their<br />

audience. Notice how Maxine Kumin’s use <strong>of</strong> precise verbs in “<strong>The</strong> Sound <strong>of</strong><br />

Night” makes the description livelier and more specific than if she had used<br />

verbs such as “fly” or “communicate.”<br />

and bats, snub seven-pointed kites,<br />

skitter across the lake, swing out,<br />

squeak, chirp, dip, and skim on skates<br />

<strong>of</strong> air . . . (lines 4–7)<br />

Careful consideration <strong>of</strong> word choice can be given to all types <strong>of</strong> writing, not<br />

just poetry. Notice that the revisions in red are precise verbs that enhance the<br />

description in this first draft. Revise your responses to the prompts by changing<br />

any dull, general verbs to more precise ones.<br />

student model<br />

urges<br />

In “<strong>The</strong>re Will Come S<strong>of</strong>t Rains,” Sara Teasdale asks us to consider that<br />

annihilated<br />

nature will go on long after humans have done away with themselves.<br />

A strong opinion statement<br />

will . . .<br />

• identify one poem as<br />

expressing the most<br />

appreciation <strong>of</strong> nature<br />

• show how the imagery and<br />

tone <strong>of</strong> the poem express<br />

this appreciation<br />

An effective response will . . .<br />

• give a clearly stated<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> each poem<br />

• present details that support<br />

the interpretation<br />

writing<br />

tools<br />

For prewriting, revision,<br />

and editing tools, visit<br />

the Writing Center at<br />

ClassZone.com.<br />

. . . s<strong>of</strong>t rains / meeting at night / the sound <strong>of</strong> night 703

704<br />

Before Reading<br />

I dwell in Possibility—<br />

Poem by Emily Dickinson<br />

Variation on a <strong>The</strong>me by Rilke<br />

Poem by Denise Levertov<br />

blessing the boats<br />

Poem by Lucille Clifton<br />

What if you couldn’t fail?<br />

KEY IDEA Think about living in a world <strong>of</strong> endless possibility. You<br />

have no limitations, and you have every advantage available to you.<br />

If you want to sing, you have an extraordinary voice. If you want to<br />

feed the hungry, world leaders adopt your plans. What would you do<br />

in life if you knew that you could only succeed?<br />

QUICKWRITE Make a short to-do list <strong>of</strong> things you’d<br />

like to accomplish if success were assured. <strong>The</strong>n, with a<br />

partner, discuss your list. What are some <strong>of</strong> the entries?<br />

How do you feel inside as you imagine completing these<br />

tasks?<br />

To-Do List<br />

1. Compete in the Olympics<br />

2.<br />

3.

poetic form: lyric poetry<br />

A lyric poem is a short poem in which a single speaker<br />

expresses personal thoughts and feelings on a subject. In<br />

ancient Greece, lyric poets expressed their feelings in song,<br />

accompanied by a lyre. While modern lyric poems are no<br />

longer sung, they still retain common characteristics such as:<br />

• a sense <strong>of</strong> rhythm and melody<br />

• imaginative language<br />

• exploration <strong>of</strong> a single feeling or thought<br />

Reading the lyric poems on the following pages aloud will help<br />

you appreciate these characteristics.<br />

literary analysis: figurative language<br />

Figurative language is an expression <strong>of</strong> ideas beyond what the<br />

words literally mean. Three basic types <strong>of</strong> figurative language,<br />

or figures <strong>of</strong> speech, follow:<br />

• A simile compares two unlike things that have something<br />

in common, using like or as. (bats, sailing like kites)<br />

• A metaphor compares two unlike things by saying that one<br />

thing actually is the other. (bats, snub seven-pointed kites)<br />

• Personification lends human qualities to an object, animal,<br />

or idea. (bats, performing a graceful ballet)<br />

Poets use figurative language both to convey abstract thoughts<br />

and to <strong>of</strong>fer a fresh outlook on everyday things. As you read<br />

the following poems, use a chart like this one to record and<br />

analyze examples <strong>of</strong> simile, metaphor, and personification.<br />

Example Type Two Things<br />

Compared<br />

“I dwell in<br />

Possibility—/ A<br />

fairer House than<br />

Prose–”<br />

metaphor poetry/possibility<br />

and a house<br />

reading skill: compare and contrast<br />

Ideas<br />

Suggested<br />

Comparing and contrasting the poems—identifying the<br />

similarities and the differences between them—will help you<br />

understand each poem’s central theme. As you read, compare<br />

the feelings expressed and the figurative language used.<br />

Emily Dickinson:<br />

Passionate Poet<br />

As an adult, Emily<br />

Dickinson rarely left<br />

her father’s home or<br />

welcomed visitors.<br />

Yet she managed to<br />

write poems that<br />

are remarkable for<br />

their originality and<br />

awareness <strong>of</strong> human<br />

passion. Using unusual<br />

imagery and syntax,<br />

she explored such powerful emotions as<br />

love, despair, and ecstasy.<br />

Denise Levertov:<br />

A Poetic Vocation<br />

Denise Levertov’s<br />

view that writing<br />

poetry should be like<br />

a religious calling was<br />

influenced by the early<br />

20th-century poet<br />

Rainer Maria Rilke,<br />

whom she claimed as<br />

a role model. Levertov<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten used her art in<br />

service <strong>of</strong> political<br />

ideals, tackling such issues as the Vietnam<br />

War and the nuclear arms race.<br />

Lucille Clifton:<br />

Honoring Heritage<br />

Lucille Clifton’s<br />

poetry honors African<br />

heritage and expresses<br />

optimism about life.<br />

Clifton is a pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

<strong>of</strong> humanities at<br />

St. Mary’s College,<br />

which boasts a<br />

premier varsity sailing<br />

program. Sailboat<br />

races there may have<br />

inspired “blessing the boats.”<br />

Emily Dickinson<br />

1830–1886<br />

Denise Levertov<br />

1923–1997<br />

Lucille Clifton<br />

born 1936<br />

more about the author<br />

For more on these poets, visit the<br />

Literature Center at ClassZone.com.<br />

705

706 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

5<br />

10<br />

I dwell in Possibility—<br />

emily dickinson<br />

I dwell in Possibility—<br />

A fairer House than Prose—<br />

More numerous <strong>of</strong> Windows—<br />

Superior—for Doors— a<br />

Of Chambers as the Cedars—<br />

Impregnable 1 <strong>of</strong> Eye—<br />

And for an Everlasting Ro<strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Gambrels 2 <strong>of</strong> the Sky— b<br />

Of Visitors—the fairest—<br />

For Occupation—This—<br />

<strong>The</strong> spreading wide my narrow Hands<br />

To gather Paradise—<br />

1. Impregnable: unconquerable.<br />

2. Gambrels: a type <strong>of</strong> ro<strong>of</strong> with two slopes on each side.<br />

a FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE<br />

<strong>The</strong> speaker is not literally<br />

living in a House <strong>of</strong><br />

Possibility. What idea is<br />

really being conveyed in<br />

this metaphor?<br />

b FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE<br />

An extended metaphor<br />

compares two unlike<br />

things in more than one<br />

way. <strong>The</strong> house metaphor<br />

continues from the first<br />

stanza to the next. In lines<br />

5–8, what is Dickinson<br />

saying about the size and<br />

scope <strong>of</strong> this house?<br />

Detail <strong>of</strong> Cape Cod Morning (1950),<br />

Edward Hopper. Oil on canvas,<br />

34 1 /8˝ × 40 1 /4˝. Smithsonian<br />

American Art Museum, Washington,<br />

D.C. © Heirs <strong>of</strong> Josephine N.<br />

Hopper, licensed by the Whitney<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> American Art.

ANALYZE VISUALS<br />

In what way does this<br />

image illustrate the<br />

feelings expressed in<br />

Dickinson’s poem?<br />

Give specific details.<br />

i dwell in possibility 707

708<br />

Variation on a <strong>The</strong>me by Rilke<br />

(<strong>The</strong> Book <strong>of</strong> Hours, Book I, Poem I, Stanza I)<br />

denise levertov<br />

A certain day became a presence to me;<br />

there it was, confronting me—a sky, air, light:<br />

a being. And before it started to descend<br />

from the height <strong>of</strong> noon, it leaned over<br />

5 and struck my shoulder as if with<br />

the flat <strong>of</strong> a sword, granting me<br />

honor and a task. <strong>The</strong> day’s blow c<br />

rang out, metallic—or it was I, a bell awakened,<br />

and what I heard was my whole self<br />

10 saying and singing what it knew: I can. d<br />

c FIGURATIVE<br />

LANGUAGE<br />

In this poem, a day is<br />

given human qualities.<br />

What idea does Levertov<br />

highlight through this<br />

use <strong>of</strong> personification?<br />

d COMPARE AND<br />

CONTRAST<br />

How similar are the<br />

feelings expressed in this<br />

poem and Dickinson’s<br />

poem?

20<br />

5<br />

10<br />

blessing the boats<br />

(at St. Mary’s)<br />

lucille clifton<br />

may the tide<br />

that is entering even now<br />

the lip <strong>of</strong> our understanding<br />

carry you out<br />

beyond the face <strong>of</strong> fear<br />

may you kiss<br />

the wind then turn from it<br />

certain that it will<br />

love your back may you<br />

open your eyes to water<br />

water waving forever<br />

and may you in your innocence<br />

sail through this to that e<br />

e LYRIC POETRY<br />

What feeling is the<br />

speaker expressing?<br />

variation on a theme by rilke / blessing the boats 709

After Reading<br />

Comprehension<br />

1. Recall In Dickinson’s poem, what is the speaker’s house “fairer than”?<br />

2. Recall What did the speaker <strong>of</strong> Levertov’s poem hear when “the day’s blow<br />

rang out”?<br />

3. Paraphrase What does the speaker <strong>of</strong> Clifton’s poem wish?<br />

Literary Analysis<br />

4. Interpret Metaphor In Dickinson’s poem, the house is the basis for a<br />

metaphor that is carried throughout the poem. What does this extended<br />

metaphor suggest about being a poet and living a life <strong>of</strong> the imagination?<br />

5. Interpret Figurative <strong>Language</strong> Reread lines 4–7 in Levertov’s poem and<br />

identify two examples <strong>of</strong> figurative language. What idea is conveyed? How<br />

does the figurative language illustrate the relationship between the speaker<br />

and the day?<br />

6. Analyze Personification Find two or three examples <strong>of</strong> personification in<br />

Clifton’s poem. What is given human qualities, and to what effect?<br />

7. Evaluate Figurative <strong>Language</strong> Refer to the chart you created as you read.<br />

Which poem made the best use <strong>of</strong> figurative language? Explain your choice.<br />

8. Compare and Contrast <strong>The</strong>mes Complete a chart like the one shown.<br />

Based on this information, do the poems suggest similar or different ideas<br />

about possibility?<br />

“I dwell in Possibility ”<br />

“Variation on a <strong>The</strong>me<br />

by Rilke”<br />

“blessing the boats”<br />

9. Evaluate Lyric Poems Review the characteristics <strong>of</strong> lyric poetry listed on page<br />

705. Which poem would work best as the lyrics <strong>of</strong> a song, and why?<br />

Literary Criticism<br />

Feelings Expressed Figurative<br />

<strong>Language</strong> Used<br />

10. Critical Interpretations French poet Jean de La Fontaine said, “Man is so made<br />

that when anything fires his soul, impossibilities vanish.” Evaluate the three<br />

poems against his statement. Do they support his claim? Why or why not?<br />

710 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry

Reading-Writing Connection<br />

Broaden your understanding <strong>of</strong> the poems by responding to these prompts.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n use Revision: Grammar and Style to improve your writing.<br />

writing prompts self-check<br />

A. Short Response: Write a Lyric Poem<br />

In four or more lines, write a poem about a feeling<br />

you’ve had. Incorporate at least two examples <strong>of</strong><br />

figurative language.<br />

B. Extended Response: Analyze <strong>The</strong>me<br />

Who or what inspires the speakers <strong>of</strong> the three<br />

poems to be open to possibility? Write three to five<br />

paragraphs in which you explore the people, places,<br />

ideas, or things that embolden the three speakers.<br />

revision: grammar and style<br />

CREATE RHYTHM Parallelism is the use <strong>of</strong> similar grammatical constructions to<br />

express ideas that are related or equal in importance. In the following excerpt<br />

from her poem “blessing the boats,” Lucille Clifton uses parallelism to add<br />

rhythmic cadence to her writing. Notice how, in two different instances, she<br />

uses an inverted sentence structure that begins with the words “may you,”<br />

followed by predicates.<br />

may you kiss<br />

the wind then turn from it<br />

certain that it will<br />

love your back may you<br />

open your eyes to water<br />

water waving forever (lines 6–11)<br />

Note how the revisions in red use parallelism to improve this first draft. Revise<br />

your responses to the prompts by making similar changes.<br />

student model<br />

A successful poem will . . .<br />

• describe a single impression<br />

• include similes, metaphors,<br />

or personification<br />

And through<br />

Through poetry, the speaker sees the unseen. <strong>Poetry</strong> also helps the speaker<br />

s<br />

experience heaven on earth.<br />

An effective analysis will . . .<br />

• include statements about<br />

the speakers’ inspiration<br />

• present details from the<br />

poems to support conclusions<br />

• devote at least one paragraph<br />

to each poem<br />

writing<br />

tools<br />

For prewriting, revision,<br />

and editing tools, visit<br />

the Writing Center at<br />

ClassZone.com.<br />

i dwell . . . / variation . . . / blessing the boats 711

712<br />

Before Reading<br />

<strong>The</strong> Fish<br />

Poem by Elizabeth Bishop<br />

Christmas Sparrow<br />

Poem by Billy Collins<br />

<strong>The</strong> Sloth<br />

Poem by <strong>The</strong>odore Roethke<br />

What animal<br />

reminds you <strong>of</strong> yourself ?<br />

KEY IDEA Think about your pets or other animals you’ve seen at the<br />

zoo or on TV nature shows. Do they ever behave in a way that seems<br />

almost human? Have you ever thought you knew what they were<br />

feeling? In the poems that follow, you will meet three animals with<br />

distinctive “human” qualities.<br />

DISCUSS Choose one animal you identify with the most. Explain to a<br />

partner why you relate to it and what characteristics you share with it.

poetic form: free verse<br />

Most modern poems are written in free verse, a poetic form<br />

with no regular pattern <strong>of</strong> rhyme or rhythm. A free verse poem<br />

can be structured as one long, unbroken stanza, as in “<strong>The</strong><br />

Fish,” or with many stanzas <strong>of</strong> varying length, as in “Christmas<br />

Sparrow.” <strong>The</strong> lines in free verse poems may also vary in<br />

length. Without a strict meter, the rhythm <strong>of</strong> free verse poetry<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten seems more like everyday speech. As you read, notice<br />

how the line length, sounds <strong>of</strong> words, and punctuation create<br />

a rhythm in each poem.<br />

literary analysis: imagery<br />

Sometimes a poem can seem like a portrait <strong>of</strong> a moment, a<br />

person, an animal, or an object. Imagery, or words and phrases<br />

that appeal to the reader’s senses, can help create these types<br />

<strong>of</strong> portraits and <strong>of</strong>ten reinforce certain ideas about the subject<br />

described. For example, in “<strong>The</strong> Fish,” Bishop appeals to the<br />

senses <strong>of</strong> sight and touch when she describes the fish’s skin.<br />

Lines like these help depict a beautifully fragile old fish.<br />

hung in strips / like ancient wallpaper<br />

shapes like full-blown roses / stained and lost through age<br />

As you read the poems, record strong, evocative imagery on a<br />

chart like the one shown. Identify<br />

• the sense the word or phrase appeals to<br />

• the associations the imagery conjures up<br />

• the idea that is being reinforced<br />

Poem Title:<br />

Imagery Sense(s) Associations Idea Reinforced<br />

reading strategy: visualize<br />

As you read the following poems, notice how the imagery,<br />

descriptions, and specific words help you visualize the animals,<br />

settings, and events in the poems. Use your imagination to<br />

“see” what they might look like. For example, what image <strong>of</strong> a<br />

fish comes to mind when you read the following description?<br />

He hung a grunting weight, / battered and venerable / and<br />

homely. . . .<br />

Elizabeth Bishop:<br />

Soulful Poet <strong>The</strong> poetry<br />

<strong>of</strong> Elizabeth Bishop is<br />

marked by its exact and<br />

tranquil descriptions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the physical world.<br />

Hidden beneath her<br />

poems’ air <strong>of</strong> serenity<br />

and simplicity, however,<br />

are underlying themes<br />

<strong>of</strong> great depth. When<br />

writing about loss<br />

and pain, the struggle to belong, and other<br />

themes, Bishop worked hard to ensure that<br />

“the spiritual [was] felt.”<br />

Billy Collins: Poet for<br />

the People Billy Collins<br />

remembers publishing<br />

a poem in his high<br />

school newspaper that<br />

was later confiscated.<br />

Rising to national and<br />

popular prominence<br />

years later, Collins<br />

became U.S. Poet<br />

Laureate (2001–2003)<br />

and launched the<br />

Elizabeth Bishop<br />

1911–1979<br />

Billy Collins<br />

born 1941<br />

“<strong>Poetry</strong> 180” program, which aimed to get<br />

more high school students to read wellwritten,<br />

understandable poetry each day<br />

during the 180-day school year.<br />

<strong>The</strong>odore Roethke:<br />

Passion for Nature<br />

“When I get alone<br />

under an open sky,”<br />

wrote <strong>The</strong>odore<br />

Roethke, “where man<br />

isn’t too evident—<br />

then I’m tremendously<br />

exalted. . . .” A passion<br />

for nature pervades<br />

Roethke’s poetry. His <strong>The</strong>odore Roethke<br />

1908–1963<br />

poems also explore<br />

love, mortality, and the<br />

quest for spiritual wholeness.<br />

more about the author<br />

For more on these poets, visit the<br />

Literature Center at ClassZone.com.<br />

713

<strong>The</strong> Fish<br />

Elizabeth Bishop<br />

714 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

I caught a tremendous fish<br />

and held him beside the boat<br />

half out <strong>of</strong> water, with my hook<br />

fast in a corner <strong>of</strong> his mouth.<br />

5 He didn’t fight.<br />

He hadn’t fought at all.<br />

He hung a grunting weight,<br />

battered and venerable<br />

and homely. Here and there a<br />

10 his brown skin hung in strips<br />

like ancient wallpaper,<br />

and its pattern <strong>of</strong> darker brown<br />

was like wallpaper:<br />

shapes like full-blown roses<br />

15 stained and lost through age.<br />

He was speckled with barnacles,<br />

fine rosettes <strong>of</strong> lime,<br />

and infested<br />

with tiny white sea-lice,<br />

20 and underneath two or three<br />

rags <strong>of</strong> green weed hung down.<br />

While his gills were breathing in<br />

the terrible oxygen<br />

—the frightening gills,<br />

25 fresh and crisp with blood,<br />

that can cut so badly—<br />

I thought <strong>of</strong> the coarse white flesh<br />

packed in like feathers,<br />

the big bones and the little bones,<br />

30 the dramatic reds and blacks<br />

<strong>of</strong> his shiny entrails,<br />

a FREE VERSE<br />

Notice how the lines <strong>of</strong><br />

this poem are unequal in<br />

length. How do the short<br />

lines affect the rhythm in<br />

the poem?

35<br />

40<br />

45<br />

50<br />

55<br />

60<br />

65<br />

70<br />

75<br />

and the pink swim-bladder<br />

like a big peony.<br />

I looked into his eyes<br />

which were far larger than mine<br />

but shallower, and yellowed,<br />

the irises backed and packed<br />

with tarnished tinfoil<br />

seen through the lenses<br />

<strong>of</strong> old scratched isinglass.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y shifted a little, but not<br />

to return my stare.<br />

—It was more like the tipping<br />

<strong>of</strong> an object toward the light. b<br />

I admired his sullen face,<br />

the mechanism <strong>of</strong> his jaw,<br />

and then I saw<br />

that from his lower lip<br />

—if you could call it a lip—<br />

grim, wet, and weaponlike,<br />

hung five old pieces <strong>of</strong> fish-line,<br />

or four and a wire leader<br />

with the swivel still attached,<br />

with all their five big hooks<br />

grown firmly in his mouth.<br />

A green line, frayed at the end<br />

where he broke it, two heavier lines,<br />

and a fine black thread<br />

still crimped from the strain and snap<br />

when it broke and he got away.<br />

Like medals with their ribbons<br />

frayed and wavering,<br />

a five-haired beard <strong>of</strong> wisdom<br />

trailing from his aching jaw. c<br />

I stared and stared<br />

and victory filled up<br />

the little rented boat,<br />

from the pool <strong>of</strong> bilge<br />

where oil had spread a rainbow<br />

around the rusted engine<br />

to the bailer rusted orange,<br />

the sun-cracked thwarts,<br />

the oarlocks on their strings,<br />

the gunnels—until everything<br />

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!<br />

And I let the fish go.<br />

b VISUALIZE<br />

Reread lines 34–44. What<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> the fish’s<br />

character can you “see” in<br />

this description <strong>of</strong> its eyes?<br />

c IMAGERY<br />

What senses does this<br />

description <strong>of</strong> the fish’s<br />

face appeal to? What<br />

associations form in your<br />

mind about the fish?<br />

the fish 715

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

Christmas<br />

Sparrow<br />

<strong>The</strong> first thing I heard this morning<br />

was a rapid flapping sound, s<strong>of</strong>t, insistent—<br />

wings against glass as it turned out<br />

downstairs when I saw the small bird<br />

rioting in the frame <strong>of</strong> a high window,<br />

trying to hurl itself through<br />

the enigma <strong>of</strong> glass into the spacious light. d<br />

<strong>The</strong>n a noise in the throat <strong>of</strong> the cat<br />

who was hunkered on the rug<br />

told me how the bird had gotten inside,<br />

carried in the cold night<br />

through the flap <strong>of</strong> a basement door,<br />

and later released from the s<strong>of</strong>t grip <strong>of</strong> teeth.<br />

On a chair, I trapped its pulsations<br />

in a shirt and got it to the door,<br />

so weightless it seemed<br />

to have vanished into the nest <strong>of</strong> cloth.<br />

But outside, when I uncupped my hands,<br />

it burst into its element,<br />

dipping over the dormant garden<br />

in a spasm <strong>of</strong> wingbeats<br />

then disappeared over a row <strong>of</strong> tall hemlocks.<br />

716 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

Billy Collins<br />

d IMAGERY<br />

What images describe the<br />

bird in lines 1–7? What<br />

senses do these images<br />

appeal to?

25<br />

30<br />

For the rest <strong>of</strong> the day,<br />

I could feel its wild thrumming<br />

against my palms as I wondered about<br />

the hours it must have spent<br />

pent in the shadows <strong>of</strong> that room,<br />

hidden in the spiky branches<br />

<strong>of</strong> our decorated tree, breathing there<br />

among the metallic angels, ceramic apples, stars <strong>of</strong> yarn,<br />

its eyes open, like mine as I lie in bed tonight e<br />

picturing this rare, lucky sparrow<br />

tucked into a holly bush now,<br />

a light snow tumbling through the windless dark.<br />

e VISUALIZE<br />

What details help you<br />

imagine how the bird<br />

looks and feels as it hides<br />

in the Christmas tree?<br />

christmas sparrow 717

<strong>The</strong><br />

Sloth<br />

<strong>The</strong>odore Roethke<br />

5<br />

10<br />

o<br />

In moving-slow he has no Peer. 1<br />

You ask him something in his Ear,<br />

He thinks about it for a Year;<br />

And, then, before he says a Word<br />

<strong>The</strong>re, upside down (unlike a Bird),<br />

He will assume that you have Heard—<br />

A most Ex-as-per-at-ing Lug.<br />

But should you call his manner Smug,<br />

He’ll sigh and give his Branch a Hug; f<br />

<strong>The</strong>n <strong>of</strong>f again to Sleep he goes,<br />

Still swaying gently by his Toes,<br />

And you just know he knows he knows.<br />

1. peer: equal.<br />

718 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

f IMAGERY<br />

Reread line 9. What does<br />

this image suggest about<br />

the sloth?

After Reading<br />

Comprehension<br />

1. Recall How does the fish in Bishop’s poem react when it is caught?<br />

2. Recall How did the bird in Collins’s poem get trapped inside the house?<br />

3. Summarize What is the sloth’s response when asked a question?<br />

Literary Analysis<br />

4. Visualize Describe in detail the mental picture you form <strong>of</strong> each animal in the<br />

poems.<br />

5. Analyze Imagery Review the examples <strong>of</strong> imagery you recorded in your chart.<br />

Identify some images that appeal to your sense <strong>of</strong> sight and others that<br />

appeal to your sense <strong>of</strong> touch. What is the most striking image in each poem?<br />

Why?<br />

6. Analyze Free Verse How is the experience <strong>of</strong> reading Bishop’s and Collins’s<br />

free verse poems different from reading Roethke’s more traditional poem?<br />

7. Interpret <strong>The</strong>mes How are the three animals in these poems like people?<br />

What does each poem suggest about the relationship between human beings<br />

and animals?<br />

8. Compare and Contrast Texts Compare and contrast the Bishop and Collins<br />

poems. In a chart like the one shown, consider subject, mood, and theme in<br />

your answer.<br />

Subject<br />

Mood<br />

<strong>The</strong>me<br />

Literary Criticism<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Fish” “Christmas Sparrow” Similarities Differences<br />

9. Critical Interpretations According to Billy Collins, the best poems begin in<br />

clarity and end in mystery. Would you say that this is true for each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

three poems in this lesson? Why or why not?<br />

the fish / christmas sparrow / the sloth 719

720<br />

Before Reading<br />

Piano<br />

Poem by D. H. Lawrence<br />

Fifteen<br />

Poem by William Stafford<br />

Tonight I Can Write . . . / Puedo Escribir<br />

Los Versos . . .<br />

Poem by Pablo Neruda<br />

Which memories last?<br />

KEY IDEA Think back to a moment from your past that evokes<br />

powerful feelings in you. Why has this memory made such a lasting<br />

impression? Was it the person you shared the experience with, or<br />

the activity itself? In the poems that follow, three speakers recall<br />

moments that have had a lasting impact.<br />

QUICKWRITE In a short paragraph, describe a particular memory.<br />

Why is this recollection special? What feelings do you remember?<br />

Include sensory details that help present a clear picture.

literary analysis: sound devices<br />

In the poems that follow, the poets use rhyme and other sound<br />

devices to convey rhythm and meaning:<br />

• Assonance—the repetition <strong>of</strong> vowel sounds in words that<br />

don’t rhyme<br />

We could find the end <strong>of</strong> a road, meet<br />

the sky on out Seventeenth. . . .<br />

• Consonance—the repetition <strong>of</strong> consonant sounds within and<br />

at the ends <strong>of</strong> words<br />

S<strong>of</strong>tly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;<br />

Taking me back down the vista <strong>of</strong> years, till I see<br />

• Repetition—a sound, word, phrase, or line that is repeated<br />

I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too.<br />

She loved me, sometimes I loved her too.<br />

Listen for the various sound devices that establish each poem’s<br />

rhythmic flow, and notice how they help to evoke specific<br />

memories. Record examples in a chart.<br />

“Piano”<br />

“Fifteen”<br />

“Tonight I Can<br />

Write . . .”<br />

reading skill: understand line breaks<br />

End-stopped lines <strong>of</strong> poetry end at a normal speech pause, as in<br />

these lines from “Tonight I Can Write . . .”:<br />

<strong>The</strong> same night whitening the same trees.<br />

We, <strong>of</strong> that time, are no longer the same.<br />

This emphasizes the line endings and makes a reader view each<br />

line as a complete unit <strong>of</strong> meaning.<br />

Enjambed lines run on without a natural pause, as in “Fifteen”:<br />

South <strong>of</strong> the bridge on Seventeenth<br />

I found back <strong>of</strong> the willows one summer<br />

day a motorcycle with engine running<br />

Enjambment can create a tension and momentum until the<br />

thought is complete. As you read each poem, think about how<br />

line breaks affect rhythm and meaning.<br />

Review: Make Inferences<br />

Assonance Consonance Repetition<br />

D. H. Lawrence: Writer<br />

<strong>of</strong> Experience<br />

Although impoverished<br />

during his childhood,<br />

D. H. Lawrence found<br />

great pleasure in<br />

learning and culture,<br />

a love <strong>of</strong> which<br />

was instilled by his<br />

mother. Lawrence’s<br />

confessional, earnest<br />

D. H. Lawrence<br />

1885–1930<br />

style is illustrated in<br />

the poem “Piano.” He<br />

wrote it in memory <strong>of</strong> his mother.<br />

William Stafford:<br />

Remembering the Past<br />

William Stafford<br />

remembered, growing<br />

up in Kansas, being<br />

“surrounded by songs<br />

and stories and poems,<br />

and lyrical splurges <strong>of</strong><br />

excited talk. . . .” <strong>The</strong>se<br />

memories eventually<br />

became the stuff <strong>of</strong><br />

his poetry. “Fifteen” is<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a collection <strong>of</strong><br />

poems that recall his past.<br />

Pablo Neruda: Boy<br />

Wonder Pablo Neruda<br />

was drawn to poetry<br />

at an early age, even<br />

though his workingclass<br />

family sc<strong>of</strong>fed at<br />

his literary ambitions.<br />

By age 20 he had<br />

achieved literary<br />

stardom with the<br />

publication <strong>of</strong> Twenty<br />

Love Poems and a Song<br />

<strong>of</strong> Despair. <strong>The</strong> book<br />

William Stafford<br />

1914–1993<br />

Pablo Neruda<br />

1904–1973<br />

chronicles a passionate love story, from the<br />

couple’s first meeting to eventual breakup.<br />

“Tonight I Can Write” is the 20th poem.<br />

more about the author<br />

For more on these poets, visit the<br />

Literature Center at ClassZone.com.<br />

721

<strong>The</strong> Spinet (1902), Thomas Wilmer Dewing. Oil on wood, 15 1 /2˝ × 20˝. Smithsonian American Art<br />

Museum, Washington, D.C. Photo © Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C./Art<br />

Resource, New York.<br />

Piano<br />

D. H. Lawrence<br />

5<br />

10<br />

S<strong>of</strong>tly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;<br />

Taking me back down the vista <strong>of</strong> years, till I see<br />

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom <strong>of</strong> the<br />

tingling strings<br />

And pressing the small, poised feet <strong>of</strong> a mother who<br />

smiles as she sings.<br />

In spite <strong>of</strong> myself, the insidious mastery <strong>of</strong> song<br />

Betrays me back, till the heart <strong>of</strong> me weeps to belong<br />

To the old Sunday evenings at home, with winter outside<br />

And hymns in the cozy parlour, the tinkling piano<br />

our guide. a<br />

So now it is vain for the singer to burst into clamour<br />

With the great black piano appassionato. <strong>The</strong> glamour<br />

Of childish days is upon me, my manhood is cast<br />

Down in the flood <strong>of</strong> remembrance, I weep like a child<br />

for the past.<br />

722 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

a SOUND DEVICES<br />

Reread lines 5–9<br />

aloud. Where can you<br />

find assonance and<br />

consonance in this<br />

stanza?

Fifteen<br />

William Stafford<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

South <strong>of</strong> the bridge on Seventeenth<br />

I found back <strong>of</strong> the willows one summer<br />

day a motorcycle with engine running<br />

as it lay on its side, ticking over<br />

slowly in the high grass. I was fifteen.<br />

I admired all that pulsing gleam, the<br />

shiny flanks, the demure headlights<br />

fringed where it lay; I led it gently<br />

to the road and stood with that<br />

companion, ready and friendly. I was fifteen. b<br />

We could find the end <strong>of</strong> a road, meet<br />

the sky on out Seventeenth. I thought about<br />

hills, and patting the handle got back a<br />

confident opinion. On the bridge we indulged<br />

a forward feeling, a tremble. I was fifteen.<br />

Thinking, back farther in the grass I found<br />

the owner, just coming to, where he had flipped<br />

over the rail. He had blood on his hand, was pale—<br />

I helped him walk to his machine. He ran his hand<br />

over it, called me good man, roared away.<br />

I stood there, fifteen.<br />

b LINE BREAKS<br />

Notice how Stafford<br />

continues a thought<br />

or sentence from one<br />

line to the next. How<br />

does this enjambment<br />

affect the way you<br />

read the lines?<br />

piano / fifteen 723

Tonight I Can Write . . .<br />

Pablo Neruda<br />

724 unit 7: the language <strong>of</strong> poetry<br />

Text not available for electronic use.<br />

Please refer to the text in the textbook.

Puedo Escribir Los Versos . . .<br />

Pablo Neruda<br />

Puedo escribir los versos más tristes esta noche.<br />

Escribir, por ejemplo: ‘La noche está estrellada,<br />

y tiritan, azules, los astros, a lo lejos.’<br />

El viento de la noche gira en el cielo y canta.<br />

5 Puedo escribir los versos más tristes esta noche.<br />

Yo la quise, y a veces ella también me quiso.<br />

En las noches como ésta la tuve entre mis brazos.<br />

La besé tantas veces bajo el cielo infinito.<br />

Ella me quiso, a veces yo también la quería.<br />

10 Cómo no haber amado sus grandes ojos fijos.<br />

Puedo escribir los versos más tristes esta noche.<br />

Pensar que no la tengo. Sentir que la he perdido.<br />

Oir la noche inmensa, más inmensa sin ella.<br />

Y el verso cae al alma como al pasto el rocío.<br />

15 Qué importa que mi amor no pudiera guardarla.<br />

La noche está estrellada y ella no está conmigo.<br />

Eso es todo. A lo lejos alguien canta. A lo lejos.<br />

Mi alma no se contenta con haberla perdido.<br />

Como para acercarla mi mirada la busca.<br />

20 Mi corazón la busca, y ella no está conmigo.<br />

La misma noche que hace blanquear los mismos árboles.<br />

Nosotros, los de entonces, ya no somos los mismos.<br />

Ya no la quiero, es cierto, pero cuánto la quise.<br />

Mi voz buscaba el viento para tocar su oído.<br />

25 De otro. Será de otro. Como antes de mis besos.<br />

Su voz, su cuerpo claro. Sus ojos infinitos.<br />

Ya no la quiero, es cierto, pero tal vez la quiero.<br />

Es tan corto el amor, y es tan largo el olvido.<br />

Porque en noches como ésta la tuve entre mis brazos,<br />

30 mi alma no se contenta con haberla perdido.<br />

Aunque éste sea el último dolor que ella me causa,<br />

y éstos sean los últimos versos que yo le escribo.<br />

Waiting (2001), Ben McLaughlin. Oil on board, 30.5 cm × 30.5 cm. Private<br />

collection. Photo © Bridgeman Art Library.<br />

tonight i can write . . . / puedo escribir . . . 725

Reading for Information<br />

JOURNAL ARTICLE In 1971, nearly 50 years after writing “Tonight I Can Write . . .” Pablo Neruda<br />

was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. For Neruda, this meant a prize <strong>of</strong> $450,000 and<br />

worldwide fame, although he was already quite famous in and around Chile, his native country.<br />

<strong>The</strong> following selection gives background on this prestigious award.<br />

<strong>The</strong><br />

In 1888, the well-known scientist and<br />