A Short History of Indonesia - 11

A Short History of Indonesia - 11

A Short History of Indonesia - 11

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

WC 4040<br />

<strong>11</strong>. A <strong>Short</strong> <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Indonesia</strong><br />

Mandalas <strong>of</strong> Power and Influence<br />

Around the year 400 AD Mulavarman gave thousands <strong>of</strong> cattle 1 , something<br />

called a “wonder tree”, and a grant <strong>of</strong> land to Brahmin priests who had<br />

consecrated him and bestowed the title “lord <strong>of</strong> kings”. This “lord <strong>of</strong> kings”<br />

ruled over a kingdom on the Mahakam River near Kutei in Kalimantan. The<br />

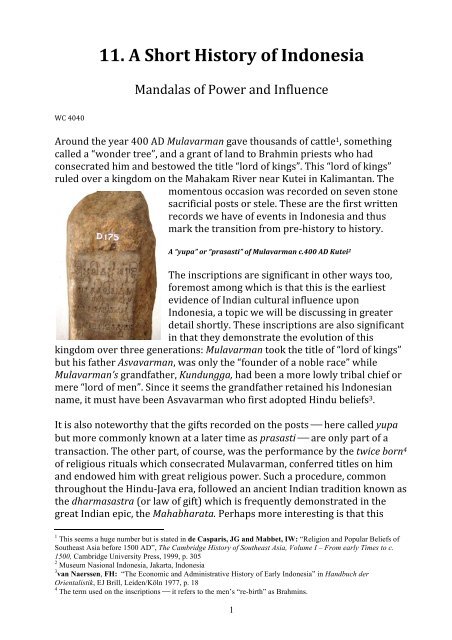

momentous occasion was recorded on seven stone<br />

sacrificial posts or stele. These are the first written<br />

records we have <strong>of</strong> events in <strong>Indonesia</strong> and thus<br />

mark the transition from pre-‐history to history.<br />

A “yupa” or “prasasti” <strong>of</strong> Mulavarman c.400 AD Kutei 2<br />

The inscriptions are significant in other ways too,<br />

foremost among which is that this is the earliest<br />

evidence <strong>of</strong> Indian cultural influence upon<br />

<strong>Indonesia</strong>, a topic we will be discussing in greater<br />

detail shortly. These inscriptions are also significant<br />

in that they demonstrate the evolution <strong>of</strong> this<br />

kingdom over three generations: Mulavarman took the title <strong>of</strong> “lord <strong>of</strong> kings”<br />

but his father Asvavarman, was only the “founder <strong>of</strong> a noble race” while<br />

Mulavarman’s grandfather, Kundungga, had been a more lowly tribal chief or<br />

mere “lord <strong>of</strong> men”. Since it seems the grandfather retained his <strong>Indonesia</strong>n<br />

name, it must have been Asvavarman who first adopted Hindu beliefs 3 .<br />

It is also noteworthy that the gifts recorded on the posts ⎯⎯ here called yupa<br />

but more commonly known at a later time as prasasti ⎯⎯ are only part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

transaction. The other part, <strong>of</strong> course, was the performance by the twice born 4<br />

<strong>of</strong> religious rituals which consecrated Mulavarman, conferred titles on him<br />

and endowed him with great religious power. Such a procedure, common<br />

throughout the Hindu-‐Java era, followed an ancient Indian tradition known as<br />

the dharmasastra (or law <strong>of</strong> gift) which is frequently demonstrated in the<br />

great Indian epic, the Mahabharata. Perhaps more interesting is that this<br />

1<br />

This seems a huge number but is stated in de Casparis, JG and Mabbet, IW: “Religion and Popular Beliefs <strong>of</strong><br />

Southeast Asia before 1500 AD”, The Cambridge <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia, Volume I – From early Times to c.<br />

1500, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 305<br />

2<br />

Museum Nasional <strong>Indonesia</strong>, Jakarta, <strong>Indonesia</strong><br />

3<br />

van Naerssen, FH: “The Economic and Administrative <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Early <strong>Indonesia</strong>” in Handbuch der<br />

Orientalistik, EJ Brill, Leiden/Köln 1977, p. 18<br />

4<br />

The term used on the inscriptions ⎯⎯ it refers to the men’s “re-birth” as Brahmins.<br />

1

ancient Hindu tradition can be traced back to<br />

even earlier Austro-‐Asiatic cultures from<br />

which both Indian and <strong>Indonesia</strong>n are<br />

ultimately derived 5 .<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia. Note the position <strong>of</strong> the Makassar<br />

Straits in relation to Java and Sumatra.<br />

There are no dates on these “sacrificial posts”<br />

but the inscriptions are written in Sanskrit in<br />

the Pallava script which itself can be dated to<br />

this period. This script evolved in southern<br />

India during the Dravidian Pallava dynasty<br />

which ruled the northern part <strong>of</strong> Tamil-‐Nadu and Andhra Pradesh from about<br />

3 rd to 5 th Centuries AD 6 . They were finally defeated by the Chola kings in the<br />

8 th Century.<br />

An example <strong>of</strong> Pallava script from India.<br />

While the stones have remained to tell us<br />

about the gifts and glorious titles <strong>of</strong><br />

Mulavarman, little else is known <strong>of</strong> him or his dynasty. While the yupa say he<br />

defeated his enemies in battle (and hence became a lord <strong>of</strong> other kings in the<br />

region) history has nothing further to say about him except that his kingdom<br />

was somewhere near the Mahakam River where it empties into the Makassar<br />

Straits. Mulavarman’s kingdom probably faded from history because other<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Indonesia</strong>, specifically Sumatra and Java grew to control the shipping<br />

lanes and consequently re-‐directed trade from India into their own ports.<br />

The trading routes <strong>of</strong> that era were largely those that brought Indian goods to<br />

Southeast Asia and returned local produce to India. Although as we have seen,<br />

China has played an important role in the pre-‐history <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia for as<br />

long as there have been people there, during this period trade was not<br />

extensive with China. Pr<strong>of</strong>essor van Naerssen 7 concluded that:<br />

As late as the third century the foreign trade <strong>of</strong> western <strong>Indonesia</strong> did not<br />

extend beyond India and Ceylon. Western <strong>Indonesia</strong> was not yet trading<br />

with China: only an <strong>Indonesia</strong>n trade with India existed. “The fifth century<br />

was a time when western <strong>Indonesia</strong>n commerce made a leap forward,<br />

benefitting from developments outside <strong>Indonesia</strong> itself by putting<br />

indigenous seamanship to good use 8 .” The regions engaged in this foreign<br />

5 van Naerssen, FH, Op. cit. p. 19<br />

6 They date originally from 275 AD but their greatest epoch was near their end, in the 7 th and 8 th Centuries.<br />

7 van Naerssen, FH, Op. cit. p. 21<br />

8 The quote is from Wolters, 1967, p.158.<br />

2

trade were South Sumatra and West Java; the kingdoms mentioned by<br />

Chinese authors were Kan-t’o-li, predecessor <strong>of</strong> the empire <strong>of</strong> Srivijaya<br />

and in West Java Ho-lo-tan. Here was the favoured commercial coast <strong>of</strong><br />

western <strong>Indonesia</strong>.<br />

Salakanagara<br />

In 1677 AD Prince Wangsakerta in Cirebon called together a symposium <strong>of</strong><br />

experts who compiled Pustaka Rayja-rayja i Bhumi Nusantara. It says that the<br />

first kingdom in Java was one called Salakanagara and that it was established<br />

in the Year 52 Saka or 130/131 AD. Although the exact location is not known,<br />

it is probable Salakanagara was in the vicinity <strong>of</strong> present-‐day Merak.<br />

Historians believe this was the city mentioned by Ptomemy <strong>of</strong> Alexandria (87-‐<br />

150 AD) in his Geographike Hypergesis. It is also mentioned in Chinese<br />

records <strong>of</strong> the time.<br />

Tarumanagara<br />

The earliest known contemporary record in Java are four prasasti <strong>of</strong><br />

Purnavarman, king <strong>of</strong> Taruma nagara. Like the yupa <strong>of</strong> Mulavarman in<br />

Kalimantan, these inscriptions are written in Pallavi but on this occasion, they<br />

date to about half a century later 9 ⎯⎯ that is, to the mid-‐5 th Century AD.<br />

3<br />

(l) prasasti tapak gajah<br />

purnawarman ⎯⎯ the<br />

Elephant’s footprints <strong>of</strong><br />

Purnavarman 10 and (r)<br />

prasasti ciarteun – note the<br />

footprints on top <strong>of</strong> the stone.<br />

Three <strong>of</strong> the prasasti were found near Bogor, south <strong>of</strong> Jakarta. On two <strong>of</strong> these<br />

footprints are carved ⎯⎯ <strong>of</strong> the illustrious Purnavarman who once ruled at<br />

Taruma ⎯⎯ and on another, the footprints <strong>of</strong> an elephant <strong>of</strong> the lord <strong>of</strong> Taruma.<br />

The fourth stone records how Purnavarman altered the course <strong>of</strong> a river and<br />

gave the Brahmins 100 cows for their part in celebrating the occasion.<br />

9 van Naerssen, op.cit. p. 23<br />

10 Photos by maskur ridwan: http://static.panoramio.com/photos/original/3754783.jpg and<br />

http://www.panoramio.com/photo/3755396

A Prasasti <strong>of</strong> Purnavarman, king <strong>of</strong> Tarumanagara,<br />

Tugu sub-district <strong>of</strong> Jakarta.<br />

One scholar commented that these inscriptions<br />

….bear ample testimony to a very high degree <strong>of</strong><br />

civilization in West Java during the fifth century<br />

<strong>of</strong> our era – a civilization which is strongly<br />

marked by Indo-Aryan influence from the<br />

mainland <strong>of</strong> India <strong>11</strong> .<br />

More is known about Purnavarman than Mulavarman. For example, we know<br />

he was the third <strong>of</strong> his dynasty to reign, the founding father being<br />

Rajadirajaguru Jayasingawarman [Raja di raja guru Jaya singa warman] who<br />

ruled from 358 to 382 AD. He was succeeded by Dharmayawarman [Dharma<br />

ya warman] 382-‐395 and then Purnavarman whose long reign extended from<br />

395 to 434 AD. According to the book Nusantara 12 , Purnavarman controlled<br />

48 small kingdoms. We also learn <strong>of</strong> Taruma Nagara from Chinese sources<br />

which record trade and diplomatic relations in the lands between China and<br />

India and more particularly, from the Buddhist monk Fa Xian who stayed on<br />

the island <strong>of</strong> Yavadi (Java) for 6<br />

months from December 412 to May<br />

413. In his book fo-kuo-chi which was<br />

written in 414 AD, Fa Xian says that<br />

little was known there about the<br />

Lord Buddha but the Brahmins and<br />

heretics flourished. Purnavarman<br />

was also mentioned in the annals <strong>of</strong><br />

the Sung dynasty because he had<br />

sent a diplomatic mission to China in<br />

435 AD, the year after the great king<br />

died.<br />

Funan and Foreign Trade<br />

Although it is clear India and China enjoyed active trade relations long into<br />

antiquity, there was relatively little trade between the <strong>Indonesia</strong>n islands and<br />

China before the Sung dynasty (960 – 1279 AD). In contrast, trade between<br />

<strong>11</strong> Vogel (1925) quoted by van Naerssen, op. cit. p23<br />

12 Nusantara means (a) those islands <strong>of</strong> the Archipelago not yet conquered by Madjapahit or (b) the whole <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Indonesia</strong> in modern times. As for (a), it is said the great general and prime minister <strong>of</strong> Madjapahit, Gadja Mada,<br />

vowed to “eat no spice” until he had conquered the whole <strong>of</strong> Nusantara (see Negarakertagama and later<br />

Pararaton). Usage (b) was coined by Ernest Francois Eugene Douwes Dekker in his 1920 book in which he tried to<br />

write a history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Indonesia</strong> without using Indian words.<br />

4

the <strong>Indonesia</strong>n islands and India was extensive and date back to the Neolithic<br />

age in the archipelago.<br />

Sanskrit and Tamil literary references to Southeast Asia may go back as<br />

far as the third century BC… By AD 70 there is evidence that cloves from<br />

the Moluccas were reaching Rome… Between the first and fifth centuries<br />

AD a number <strong>of</strong> small indigenous trading “states” (or emporia) developed<br />

in southern Indochina and in the northern part <strong>of</strong> the Malay Peninsula… 13<br />

It seems that rather than take the 1600 km voyage through the Straits <strong>of</strong><br />

Malacca and round the Malay Peninsula, the earliest traders preferred to ship<br />

their goods across the Bay <strong>of</strong> Bengal, <strong>of</strong>f-‐load them at the Isthmus <strong>of</strong> Kra,<br />

carry them overland and then take ship again across the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Thailand to an<br />

entrepôt in the Mekong Delta. The first such entrepôt was founded in the 1st<br />

Century AD at Vyadhapura (City <strong>of</strong> the Hunter – now thought to be have been<br />

the site <strong>of</strong> Angkor Borei we will mention later) which was near modern<br />

Banam in southern Cambodia, but later transferred to Oc Eo in southern<br />

Vietnam. This was probably strategically better situated but more<br />

importantly, the region was capable <strong>of</strong> producing the huge quantities <strong>of</strong> rice<br />

needed to supply the traders and the ships which came to the city. As we will<br />

see later, even the great maritime empire <strong>of</strong> Madjapahit had its centre where<br />

it did (ie, Trowulan) because this controlled the great rice bowl <strong>of</strong> Java and<br />

could therefore provision the ships and support the traders who did business<br />

with it.<br />

Although Funan rice farmers originally depended on the flooding <strong>of</strong> the river,<br />

eventually an extensive irrigation system<br />

developed. This was a system <strong>of</strong> canals so large<br />

that it connected the coastal settlements to those<br />

in region <strong>of</strong> Ankor Borei ⎯⎯ or Vyadhapura, the<br />

original entrepôt and old capital ⎯⎯ a distance <strong>of</strong><br />

over 90 km. This was so central to the well-‐being<br />

<strong>of</strong> the economy that that it must have demanded a<br />

very well organised and efficient government.<br />

Temple remains at Ankor Borei 14<br />

The volume <strong>of</strong> rice and other provisions it could<br />

supply was so important to the success <strong>of</strong> Oc Eo<br />

because ships in those days <strong>of</strong>ten had to wait in<br />

13 I have omitted the references. See the original – Bellwood, P: Prehistory <strong>of</strong> the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago.<br />

Revised ed. Honolulu: University <strong>of</strong> Hawai'i Press, 1997 – Ch. Nine: “The Early metal Phase: A Protohistoric<br />

Transition toward Supra-Tribal Societies”, epress.anu.edu.au/pima/pdf/ch09.pdf<br />

14 Photo: Kazuo Iwase,<br />

5

port for anything up to five months until the monsoon winds changed<br />

direction and allowed them to proceed on the second leg <strong>of</strong> their journey.<br />

Given that many <strong>of</strong> the traders and sailors waiting in port for the shift in the<br />

winds were from India, it is not surprising that their culture began to rub <strong>of</strong>f<br />

on the local residents, particularly the ruling élite, creating a culture change<br />

which was the beginning <strong>of</strong> what some historians have called the<br />

Indianisation or hinduization <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia 15 . Perhaps legitimising this<br />

change is a myth <strong>of</strong> origin which says that Funan was founded when a local<br />

princess raided a ship carrying an Indian prince called Kaundinya ⎯⎯ the<br />

region has always been famous for pirates ⎯⎯ but she fell in love and married<br />

Kaundinya and between them they found befriending ships rather than<br />

raiding them paid better dividends.<br />

Funan was the first <strong>of</strong> the “tiger” economies <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia, not only<br />

growing rich on the proceeds <strong>of</strong> trade and agriculture, but because it was run<br />

efficiently by an extensive bureaucracy which apparently employed Indians<br />

as its administrators. Not surprisingly therefore Funan adopted Sanskrit as<br />

the language <strong>of</strong> the court which also adopted first Hindu and later ⎯⎯ after the<br />

5 th Century AD ⎯⎯ Buddhist religious beliefs and practices. Taxes were<br />

collected in kind, in gold, silver, pearls and perfumed woods. Justice was <strong>of</strong><br />

the trial by ordeal kind, accused persons being required to carry red-‐hot iron<br />

chains or snatch gold rings or eggs from boiling water. The Funanese had<br />

slaves but, on the lighter side, they also developed music melliferous enough<br />

to impress the Chinese emperor when he heard a visiting Funanese orchestra<br />

and they had an extensive system <strong>of</strong> libraries and archives.<br />

Although the language and ethnic origins <strong>of</strong> the people <strong>of</strong> Funan are<br />

unknown, Funan is presumed to have been the first <strong>of</strong> the Khmer kingdoms.<br />

This presumption rests mainly on the myth <strong>of</strong> origin, <strong>of</strong> the pirate queen and<br />

Kaudinya mentioned earlier, a myth which is shared by the Khmer kingdom<br />

<strong>of</strong> Chenla which in the period eventually defeated and absorbed Funan.<br />

Chenla originally had its capital at Shreshthapura located in modern day<br />

southern Laos but from about 550 AD it was a vassal <strong>of</strong> Funan. However, 60<br />

or so years later it rebelled. Led by its most famous king, Ishanavarman, by<br />

sometime between 612 and 628 AD Chenla had not only defeated its former<br />

master but proceeded to absorb the whole <strong>of</strong> Funan, the people, the economy<br />

and the culture into its own. Of course, Chenla itself was eventually<br />

transformed by Jayavarman II into a kingdom called Kambuja (790 AD) which<br />

later became the much more famous Angkor. Jayavarman in his early life had<br />

15 The best-known <strong>of</strong> whom was G. Coedès: Les États hindouisés d’Indochine et d’Indonesie, 1964 (the original<br />

under a slightly different title was published in 1944; translated as The Indianized States <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia by Susan<br />

Brown Cowing, 1968)<br />

6

lived as a prince ⎯⎯ perhaps as a hostage ⎯⎯ at the court <strong>of</strong> the Sailendras in<br />

Java, the history <strong>of</strong> which we will look at later. However, in 802 AD<br />

Jayavarman II undertook a Hindu ritual and became Chakravartin which<br />

established him as a divinely appointed king and free <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> Java. He<br />

died in 834 and was succeeded by Indravarman who greatly extended the<br />

kingdom and undertook many projects including building temples and<br />

irrigation works. In turn, Indravarman was succeeded in 889 AD by<br />

Yasovarman I who built the first city <strong>of</strong> Angkor and the East Baray, the<br />

gigantic water reservoir which in its day held 50 million cubic meters <strong>of</strong><br />

water. While some scholars still hold the purpose <strong>of</strong> this artificial lake was to<br />

hold water for the irrigation canals on which the people depended for their<br />

rice production, modern thought is swinging in the direction that the purpose<br />

was purely symbolic, representing<br />

to the people the seas which<br />

surrounded Mount Meru on which<br />

the Hindu gods were believed to<br />

dwell. Today the monumental<br />

construction is bone dry and<br />

farmers cultivate its dry bed.<br />

Nonetheless, its outline ⎯⎯ like the<br />

great Wall <strong>of</strong> China ⎯⎯ can be seen<br />

from space.<br />

7<br />

East Baray June 2009 16<br />

Funan was probably at the peak <strong>of</strong> its powers in the 4 th Century and had faded<br />

away by the end <strong>of</strong> the 7 th Century. Its fall had many causes but paramount<br />

was the development <strong>of</strong> better ships and new sailing skills which in turn<br />

meant that Indian and other traders from the West no longer needed to rely<br />

on portage <strong>of</strong> their goods across the Isthmus <strong>of</strong> Kra but instead could sail the<br />

long way round, through the Straits <strong>of</strong> Malacca. Even during the hey-‐day <strong>of</strong><br />

Funan, several ports east <strong>of</strong> the Malay Peninsula and in the Sunda Straits 17<br />

had been trading direct with India as well as with Funan. <strong>Indonesia</strong>n sailors<br />

had also long been introducing local products into the international markets.<br />

Originally Indian and Chinese traders were interested only in what each could<br />

exchange with the other, but gradually they found value in <strong>Indonesia</strong>n<br />

substitutes for sought-‐after products: for example, Sumatran pine resin and<br />

benzoin gradually replaced the more expensive frankincense and myrrh.<br />

Eventually, demand for other products such as sandalwood from Timor,<br />

camphor from Sumatra and <strong>of</strong> course, spices from the Moluccas began to<br />

16 Photo: John, http://picasaweb.google.com/lh/photo/hRK3cAv2kagsuRiZoNlGYw<br />

17 The Sunda Straits are between western Java and southern Sumatra.

focus attention directly on the <strong>Indonesia</strong>n ports as trading destinations in<br />

their own right.<br />

The first and the most long-‐lived <strong>of</strong> all the <strong>Indonesia</strong>n kingdoms to emerge<br />

was Srivijaya, a maritime power we will look at in the next Unit. However,<br />

before proceeding, there are two issues we need to examine briefly because<br />

they affect how we understand the centres <strong>of</strong> power which form the subject <strong>of</strong><br />

the next section <strong>of</strong> this course. These issues are (a) what do we understand by<br />

“kingdom” in Southeast Asia and the <strong>Indonesia</strong>n archipelago in particular;<br />

and (b) to what extent were these cultures “hinduized” and how did it<br />

happen?<br />

The Mandalas <strong>of</strong> Power<br />

Up to this stage I have been referring to “kings” and “kingdoms” but<br />

historians warn these terms are misleading when used in the Southeast Asian<br />

context. Much is lost in the translation, first because kings and kingdoms were<br />

in many ways different from the<br />

European model we have in our<br />

heads, and second, because we<br />

underestimate the strength <strong>of</strong> the<br />

religious component <strong>of</strong> “kingship”.<br />

8<br />

Buddhist monk creating a sand mandala 18<br />

Some historians have suggested the<br />

word mandala be used instead <strong>of</strong><br />

kingdom in order to avoid any<br />

confusion. The word itself comes from the Sanskrit meaning a circle, the<br />

circumference <strong>of</strong> a circle or completion but it implies much more than a simple<br />

circle. It is a pattern, a constellation which variously has been used to<br />

represent the cosmos, the unity <strong>of</strong> life and even the unconscious self 19 .<br />

Perhaps the best-‐known mandalas are those made from coloured sand by<br />

Tibetan monks.<br />

To call a Southeast Asian kingdom a mandala, argues Martin Stuart-‐Fox 20 ,<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> history at the University <strong>of</strong> Queensland…<br />

….is to draw attention, metaphorically, to relations <strong>of</strong> power that<br />

connected the periphery to the centre. The mandalas <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia<br />

were constellations <strong>of</strong> power, whose extent varied in relation to the<br />

18 http://www.clemson.edu/newsroom/articles/2008/march/IAW2008.php5<br />

19 Carl Jung used it as a representation <strong>of</strong> the unconscious self<br />

20 Stuart-Fox, M: A <strong>Short</strong> <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> China and Southeast Asia ⎯⎯ Tribute, Trade and Influence, Allen and Unwin<br />

2003.

attraction <strong>of</strong> the centre. They were not states whose administrative<br />

control reached to defined frontiers. Power diminished with distance from<br />

the centre, frontiers fluctuated, and relations with neighbouring<br />

mandalas tended to be antagonistic, as each attempted to expand at the<br />

other’s expense 21 .<br />

So, for example, Stuart-‐Fox suggests we should not think <strong>of</strong> Funan as a<br />

…centralised kingdom extending from southern Vietnam all the way<br />

round to the Kra Isthmus, but rather as a mandala, the power <strong>of</strong> whose<br />

capital in southeastern Cambodia waxed and waned, and whose armed<br />

merchant ships succeeded in enforcing its temporary suzerainty over<br />

small coastal trading ports around the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Thailand. What gave Funan<br />

the edge over others such centres <strong>of</strong> power was clearly its position astride<br />

the India-China trade route. Its power, however, is unlikely to have spread<br />

further inland. Further north, on the middle Mekong and on the lower<br />

Chao Phraya River, other centres were establishing themselves that in<br />

time would challenge and replace Funan 22 .<br />

Religion and kingship were inextricably intertwined in Southeast Asia. As we<br />

saw earlier, the so-‐called Big Men had attributed to them<br />

…an abnormal amount <strong>of</strong> personal and innate “soul stuff”, which<br />

explained and distinguished their performance from that <strong>of</strong> others in<br />

their generation and especially among their own kinsmen. 23<br />

Given the cognatic kinship system <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia, in which descent was<br />

reckoned through both sides <strong>of</strong> the family, this “soul stuff” was not so much<br />

inherited but something more akin to a gift <strong>of</strong> the gods. If ancestry had<br />

anything to do with a person’s importance it was not whose son or daughter<br />

he or she happened to be but rather how many outstanding ancestors there<br />

were in the history <strong>of</strong> the extended family. Most importantly, when these Big<br />

Men died, they were recognised as Ancestors who in life had brought benefits<br />

to their community and, by extrapolation, would therefore continue to do so<br />

in the After-‐Life. As Wolters says, No special respect was paid to mere<br />

forebears in societies which practised cognatic kinship. Ancestor status had to<br />

be earned. And he added, Sites associated with the Ancestors, such as<br />

mountains, supplied additional identity to the settlement areas. 24<br />

21 Ibid, p. 29<br />

22 Ibid., pp29-30.<br />

23 Wolters, OW: <strong>History</strong>, “Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives”, Studies on Southeast Asia, Vol 26<br />

– Revised edition in cooperation with the ISEAS. p. 18<br />

24 Ibid. p 19.<br />

9

Leaders who did great deeds ⎯⎯ won wars, donated land, built temples ⎯⎯<br />

probably anticipated that they could become Ancestors and so in their<br />

lifetimes attributed their successes to divine forces and chose their burial<br />

sites with an eye to these becoming shrines and places <strong>of</strong> pilgrimage in the<br />

future. Thus, in 802 AD, for example, the Cambodian king Jayavarman II<br />

inaugurated a cult known as devaraja on Mount Mahendra. This identified<br />

him with the god Siva who was king <strong>of</strong> the gods just as he, Jayavarman was<br />

king <strong>of</strong> men. It also established him as cakravartin or universal king who, long<br />

after his death could lend spiritual power to future rulers <strong>of</strong> Cambodia and<br />

thereby protect the realm from warring factions.<br />

Although we in the West remember the divine right <strong>of</strong> kings in European<br />

history, the notion <strong>of</strong> god-‐king is very foreign to us. In fact, in all three <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Abrahamic religions ⎯⎯ Islam, Judaism and Christianity ⎯⎯ the very thought is<br />

blasphemous and the idea <strong>of</strong> a king being absorbed as it were into the identity<br />

<strong>of</strong> a god is unthinkable. However, emperors <strong>of</strong> Rome were deified after their<br />

deaths and even Antinöus, the young lover <strong>of</strong> the Emperor Claudius, was<br />

deified after he drowned in the Nile and worshipped thereafter for several<br />

centuries conflated with the Egyptian god Osiris and for a time in<br />

Antinopolus, even with Jesus.<br />

The notion however was part <strong>of</strong> the currency <strong>of</strong> kingship in Southeast Asia.<br />

When Indian religious practises were first brought to the region they were<br />

organised around cults <strong>of</strong> Siva and ⎯⎯ less <strong>of</strong>ten ⎯⎯ Vishnu. Various teacher-‐<br />

inspired sects also existed in which the gurus taught that by way <strong>of</strong> ascetic<br />

practices and the pious cultivation <strong>of</strong> his mind ⎯⎯ meditation ⎯⎯ an individual<br />

could enter into a close relationship with a particular god. In the case <strong>of</strong> kings,<br />

several close relationships <strong>of</strong> the divine kind included being a portion <strong>of</strong> Siva<br />

or participating in his divine energy. 25 This meant that the king participated in<br />

Siva’s divine authority and consequently, his personal authority was absolute.<br />

Further, since obeying the king became in effect an act <strong>of</strong> homage to Siva,<br />

obedience to the king was one way his subjects could enter into a closer<br />

relationship for themselves with the god.<br />

25 Ibid p. 22.<br />

26 Ibid p. 22.<br />

“Kingship”, signified by the personal Siva cult <strong>of</strong> the man who had seized<br />

the overlordship and not by territorially-defined “kingdoms”, was the<br />

reality that emerged from the “Hinduizing” process, but this does not<br />

mean that widely extending territorial relations were not possible. On the<br />

contrary, there need be no limit to a ruler’s sovereign claims on earth 26 .<br />

10

The Hinduized states <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the greatest <strong>of</strong> the pre-‐historians <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia was George Coedès.<br />

Born in Paris in 1886, he moved to Thailand in 1918 when he was appointed<br />

director <strong>of</strong> the National Library. In 1929 he became the director <strong>of</strong> L'École<br />

française d'Extrême-‐Orient in Hanoi where he had studied as a younger man.<br />

Coedès served there until his retirement in 1946 after which he returned to<br />

Paris as Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asian <strong>History</strong> at L'Ecole des Langues<br />

Orientales and curator <strong>of</strong> the Musée d'Ennery until his death in 1969. Apart<br />

from his many influential papers, Coedès’ two books 27 most recently re-‐<br />

published in English translation in the 1960s have long been principal texts<br />

for students <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asian history. Of these, The Indianized States <strong>of</strong><br />

Southeast Asia was first published in 1944 and perhaps more than any other<br />

in the field, has influenced the way scholars have approached their field.<br />

As it happens, after Coedès’ death, his collection was bought by the National<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> Australian. Ann Nugent, writing in the Library’s News in 1996<br />

summed up the great man’s achievements thus:<br />

His great legacy to scholars is his documentation <strong>of</strong> the cultural influence<br />

<strong>of</strong> India in most parts <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia. That influence brought Hindu<br />

and Buddhist religious ideas, the Indian concept <strong>of</strong> kingship, the use <strong>of</strong><br />

Sanskrit as an <strong>of</strong>ficial and ceremonial language, as well as Indian artistic<br />

traditions to the peoples <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia 28 .<br />

Although one cannot diminish Coedès’s contribution, an unexpected<br />

consequence <strong>of</strong> his focus upon the influence <strong>of</strong> India upon cultures in<br />

Southeast Asia has been to underestimate the strength and persistence <strong>of</strong><br />

indigenous cultures. For a time, scholars seemed to be conceptualising<br />

<strong>Indonesia</strong>n kingdoms (or mandalas) as though they were colonies <strong>of</strong> India.<br />

More recent studies suggest that although Indian beliefs and practices<br />

influenced the courts <strong>of</strong> the island kingdoms, the ordinary people were<br />

scarcely affected except perhaps when they were required to participate in<br />

ceremonies which enhanced the ruler’s status or were required to assist in<br />

the building <strong>of</strong> the many temples rulers caused to be built during their reign.<br />

There is no evidence that Brahmin priests or Buddhist monks were ever<br />

imported in any great number into Java, for example, and there is certainly no<br />

27 These books are now available as: Les peuples de la peninsule indochinoise, Dunod, Paris (1962)<br />

The Making <strong>of</strong> South East Asia, Routledge and Kegan-Paul, English translation by H. M. Wright. (1966)<br />

Les États hindouisés d’Indochine et d’Indonesie, de Boccard, Paris (1964); The Indianized States <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia,<br />

ANU Press, Canberra, English translation by Susan Brown Cowing, (1968, 1975)<br />

28 Nugent, A: “Asia's french connection : George Coedes and the Coedes collection”,<br />

National Library <strong>of</strong> Australia News, 6 (4), January 1996, pp 6-‐8.<br />

http://www.nla.gov.au/asian/form/coedes2.html<br />

<strong>11</strong>

evidence <strong>of</strong> proselytizing. Furthermore, although many <strong>of</strong> the great<br />

monuments, such as Borobudor and Prambanam, tell Indian stories such as<br />

the life <strong>of</strong> Buddha or the Ramayana, the people depicted in the masterful<br />

stone bas-‐reliefs are <strong>Indonesia</strong>n, not Indian people. Scholars nowadays seem<br />

to be leaning towards the view that aspects <strong>of</strong> Indian culture were imported<br />

by rulers <strong>of</strong> local polities, <strong>of</strong>ten to enhance their own status but that these<br />

were transformed into <strong>Indonesia</strong>n beliefs and practices, sometimes by<br />

identifying them with indigenous traditions, sometimes by re-‐working them<br />

until they fitted more comfortably into the local culture and its values. That<br />

there was Indian cultural influence upon <strong>Indonesia</strong> is undeniable but we need<br />

be wary not to over-‐emphasise it despite Coedès’ catchy title.<br />

_____________________________________________________________________<br />

12