Post-Perestroika Warrior - Passport magazine

Post-Perestroika Warrior - Passport magazine

Post-Perestroika Warrior - Passport magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

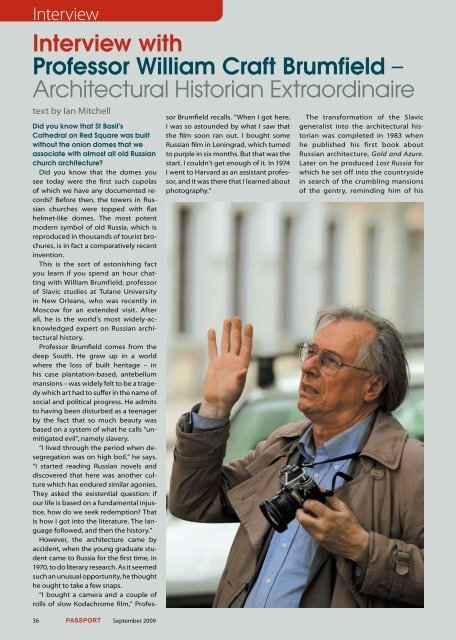

Interview<br />

Interview with<br />

Professor William Craft Brumfield –<br />

Architectural Historian Extraordinaire<br />

text by Ian Mitchell<br />

Did you know that St Basil’s<br />

Cathedral on Red Square was built<br />

without the onion domes that we<br />

associate with almost all old Russian<br />

church architecture?<br />

Did you know that the domes you<br />

see today were the first such cupolas<br />

of which we have any documented records?<br />

Before then, the towers in Russian<br />

churches were topped with flat<br />

helmet-like domes. The most potent<br />

modern symbol of old Russia, which is<br />

reproduced in thousands of tourist brochures,<br />

is in fact a comparatively recent<br />

invention.<br />

This is the sort of astonishing fact<br />

you learn if you spend an hour chatting<br />

with William Brumfield, professor<br />

of Slavic studies at Tulane University<br />

in New Orleans, who was recently in<br />

Moscow for an extended visit. After<br />

all, he is the world’s most widely-acknowledged<br />

expert on Russian architectural<br />

history.<br />

Professor Brumfield comes from the<br />

deep South. He grew up in a world<br />

where the loss of built heritage – in<br />

his case plantation-based, antebellum<br />

mansions – was widely felt to be a tragedy<br />

which art had to suffer in the name of<br />

social and political progress. He admits<br />

to having been disturbed as a teenager<br />

by the fact that so much beauty was<br />

based on a system of what he calls “unmitigated<br />

evil”, namely slavery.<br />

“I lived through the period when desegregation<br />

was on high boil,” he says.<br />

“I started reading Russian novels and<br />

discovered that here was another culture<br />

which has endured similar agonies.<br />

They asked the existential question: if<br />

our life is based on a fundamental injustice,<br />

how do we seek redemption? That<br />

is how I got into the literature. The language<br />

followed, and then the history.”<br />

However, the architecture came by<br />

accident, when the young graduate student<br />

came to Russia for the first time, in<br />

1970, to do literary research. As it seemed<br />

such an unusual opportunity, he thought<br />

he ought to take a few snaps.<br />

“I bought a camera and a couple of<br />

rolls of slow Kodachrome film,” Profes-<br />

September 2009<br />

sor Brumfield recalls. “When I got here,<br />

I was so astounded by what I saw that<br />

the film soon ran out. I bought some<br />

Russian film in Leningrad, which turned<br />

to purple in six months. But that was the<br />

start. I couldn’t get enough of it. In 1974<br />

I went to Harvard as an assistant professor,<br />

and it was there that I learned about<br />

photography.”<br />

The transformation of the Slavic<br />

generalist into the architectural historian<br />

was completed in 1983 when<br />

he published his first book about<br />

Russian architecture, Gold and Azure.<br />

Later on he produced Lost Russia for<br />

which he set off into the countryside<br />

in search of the crumbling mansions<br />

of the gentry, reminding him of his