Our money, our rights: - Consumers International

Our money, our rights: - Consumers International

Our money, our rights: - Consumers International

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

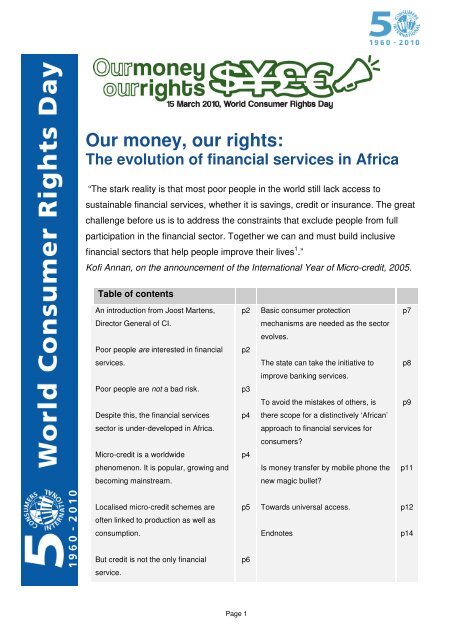

<strong>Our</strong> <strong>money</strong>, <strong>our</strong> <strong>rights</strong>:<br />

The evolution of financial services in Africa<br />

“The stark reality is that most poor people in the world still lack access to<br />

sustainable financial services, whether it is savings, credit or insurance. The great<br />

challenge before us is to address the constraints that exclude people from full<br />

participation in the financial sector. Together we can and must build inclusive<br />

financial sectors that help people improve their lives 1 .”<br />

Kofi Annan, on the announcement of the <strong>International</strong> Year of Micro-credit, 2005.<br />

Table of contents<br />

An introduction from Joost Martens,<br />

Director General of CI.<br />

Poor people are interested in financial<br />

services.<br />

Poor people are not a bad risk.<br />

Despite this, the financial services<br />

sector is under-developed in Africa.<br />

Micro-credit is a worldwide<br />

phenomenon. It is popular, growing and<br />

becoming mainstream.<br />

Localised micro-credit schemes are<br />

often linked to production as well as<br />

consumption.<br />

But credit is not the only financial<br />

service.<br />

p2<br />

p2<br />

p3<br />

p4<br />

p4<br />

p5<br />

p6<br />

Page 1<br />

Basic consumer protection<br />

mechanisms are needed as the sector<br />

evolves.<br />

The state can take the initiative to<br />

improve banking services.<br />

To avoid the mistakes of others, is<br />

there scope for a distinctively ‘African’<br />

approach to financial services for<br />

consumers?<br />

Is <strong>money</strong> transfer by mobile phone the<br />

new magic bullet?<br />

Towards universal access.<br />

Endnotes<br />

p7<br />

p8<br />

p9<br />

p11<br />

p12<br />

p14

An introduction from Joost Martens, Director General of <strong>Consumers</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong>.<br />

Access to stable, secure and fair financial services is important for consumers<br />

everywhere, including Africa. Despite relatively low levels of coverage by the formal<br />

banking sector, studies show that African consumers are willing and able to use a<br />

variety of financial services. Commonly held myths that poor consumers present<br />

too great a risk or are simply not interested in financial services are not borne out<br />

by the facts. Indeed, the phenomenon of micro-finance has firmly taken hold on the<br />

continent and is set to grow significantly. Nevertheless, despite demand, the<br />

financial services market is still significantly under-developed, and consumers go<br />

under-served. The evolution of financial services provision in Africa presents a<br />

number of interesting questions. Will African consumers be spared the negative<br />

consequences of mistakes made by others? Will governments promote the right<br />

conditions for this sector to thrive and work with all stakeholders to ensure that the<br />

consumer interest is upheld?<br />

This briefing explores the latest developments in this ongoing story. It is produced<br />

by <strong>Consumers</strong> <strong>International</strong> (CI) as part of celebrations for World Consumer Rights<br />

Day 2010.<br />

Poor people are interested in financial services.<br />

Savings ratios (ie the percentage of household income put aside), for example, are<br />

higher in middle-income countries (26%) than in high-income countries (23% 2 ). In<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) the level is far from negligible at 15%. In 2000, Uganda<br />

had a rate of 3.5% (a similar level to that of the United States before global financial<br />

crisis), while the figure for the wider COMESA (Common Market for Eastern and<br />

Southern Africa) region was 18% 3 . This indicates a significant variability within and<br />

between regions.<br />

Page 2

Although formal banking coverage is low among households in much of Africa,<br />

levels do vary. Less than one fifth of households in Kenya and Zambia, and about a<br />

fifth in Ghana, are covered, while in South Africa and Namibia the level is closer to<br />

50% 4 .<br />

However, CI’s recent publication <strong>Our</strong> <strong>money</strong>, <strong>our</strong> <strong>rights</strong>: how the global consumer<br />

movement is fighting for fair financial services, points out that poor families often<br />

have to display a degree of financial sophistication which has not been fully<br />

appreciated in the past. Portfolios of the Poor, a publication by the Financial Access<br />

Initiative, studied 250 poor households in India, Bangladesh and South Africa over<br />

one year 5 . The researchers found that all the families dealt with at least f<strong>our</strong> types<br />

of financial instrument over the c<strong>our</strong>se of the year and rural households had total<br />

cash flows equal to 10 to 30 times their end-of-year asset values. The sheer<br />

complexity of transactions (involving savings clubs, banks, formal and informal<br />

institutions, savings and debts) belies the idea of the poor as financially ignorant. In<br />

fact, the sums of <strong>money</strong> are simply less than those transacted by wealthier people.<br />

Poor people are not a bad risk.<br />

Most poor consumers manage their financial affairs responsibly. Evidence of<br />

consumer capability in this regard can be found, for example, in the very low rates<br />

of default in micro-credit. Loan repayment rates in excess of 95% are the norm, and<br />

have remained so for at least a decade 6 . The rate for some micro-credit schemes in<br />

Senegal, for example, stands at 98.5% 7 . Although micro-credit in Africa is generally<br />

for production, not consumption, when it is for consumption it is often for ‘one off’<br />

life events such as marriages and funerals, and not for trivial items 8 .<br />

Page 3

While arrears rates have slightly increased since the global financial crisis, levels<br />

still remain very low. The World Bank’s <strong>International</strong> Finance Corporation (IFC) has<br />

collated data from the top 150 micro-finance institutions showing that, globally, the<br />

proportion of borrowers 30 days behind on loans has risen from 1.2% before the<br />

financial crisis, to 2-3% in 2009 9 .<br />

Despite this, the formal financial services sector is under-developed in Africa.<br />

The UN bluebook Building inclusive financial sectors for development reported in<br />

2006 that risks in lending to the poor have been consistently overrated 10 . Repeated<br />

surveys have reported that although only a small proportion of African households<br />

are covered by the formal banking sector, many more make regular savings<br />

through less formal institutions, such as the susu system in Ghana (based on small<br />

daily collections) and savings and credit co-operatives, as in Tanzania 11 .<br />

Micro-credit is a worldwide phenomenon. It is popular, growing and<br />

becoming mainstream, in Africa too.<br />

As long ago as 2000, a study by the UK Department for <strong>International</strong> Development<br />

(DFID) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 12 found that the<br />

informal sector appeals to poor consumers because:<br />

• they welcome the combination of self-discipline and informality<br />

• small deposits are possible<br />

• doorstep services use a personal approach (no references required, for<br />

example)<br />

• there can be an easy mix with social activities (such as church gatherings)<br />

• loans can be made flexibly over different time periods and varying amounts.<br />

Page 4

This prognosis has been borne out by events. Interest in micro-finance from the<br />

formal sector is increasing. The IFC gave 55% more every year to micro-finance<br />

lenders between 2004 and 2007, and at the global level micro-finance portfolios of<br />

private investment funds grew from $600 million in 2004 to $2 billion in 2006 13 . In<br />

South Africa, micro-lending tripled between 1995 and 1997. The country’s<br />

commercial banks also started micro-lending and have come to dominate the<br />

market. By 2005, banks accounted for 50% of outstanding micro-loans, with<br />

retailers and cash lenders making up 48% 14 .<br />

Conversely, micro-finance institutions (MFI) are now evolving in the direction of the<br />

mainstream. For example, Equity Bank in Kenya registered as an MFI in 1984 and<br />

is now a full commercial bank with 52% of Kenyan bank accounts and 3.9 million<br />

clients 15 . It has targeted the base of the pyramid through specific products such as<br />

fanikisha (Swahili for ‘enable’) loans for women, of which 80,000 have been issued<br />

with up to two years duration. Vijana (Swahili for ‘good things for young people’)<br />

loans are aimed at the youth market, and number some 50,000 according to recent<br />

estimates. In Ghana some highly specific micro-finance products have been<br />

developed, for example, for AIDS sufferers 16 .<br />

Localised micro-credit schemes are often linked to production as well as<br />

consumption.<br />

Micro-credit can be used to help households and communities develop<br />

infrastructure services such as drinking water. Involvement of micro-finance in the<br />

water sector was recommended by the Camdessus report Water for All in 2003,<br />

long before the present crisis saw a downturn in private institutional investment and<br />

a decline in development aid 17 . Involvement of micro-credit in infrastructure<br />

development can be seen on a small scale in Burkina Faso, Kenya and Ethiopia 18 .<br />

Page 5

In Ethiopia it has evolved from individual revolving credit used by women, to a more<br />

collective system for funding water facilities through the Amhara Credit & Savings<br />

Institute 19 . The Moroccan government has legislated to enable micro-credit to be<br />

used for the development of electricity and drinking water supply, as well as<br />

housing for poor households 20 . Micro-credit can be used to finance first time<br />

connections and may extend from the individual to the collective, so that families<br />

invest in their own communal development.<br />

A distinctive feature of Africa, particularly rural areas, is that the distinction between<br />

the consumer and producer is more blurred. Many of the activities supported by<br />

micro-loans for small businesses (such as baking, cloth dyeing, market gardening)<br />

often take place either in, or in close proximity to the home. In Kenya 80% of micro-<br />

enterprises are owned by women 21 . Under those circumstances there are likely to<br />

be spin offs that benefit families as consumers as well as producers.<br />

But credit is not the only financial service.<br />

At a World Bank conference in 2000, it was reported that ‘there is a larger market<br />

for savings products than for credit products as has been demonstrated repeatedly<br />

by micro-finance organisations, which consistently report loan/deposit ratios of less<br />

than 50% 22 .’ Similarly, the above mentioned DFID/UNDP study points out that<br />

financial services providers need to diversify. Savings and risk pooling (insurance)<br />

are also essential services that are comprehensible to a wide range of consumers<br />

and yet under-provided. The Agence Francaise de developpement has also<br />

reported an evolution from micro-credit to micro-finance in Africa, widening in scope<br />

to include insurance and <strong>money</strong> transfer in addition to the now traditional micro-<br />

loans 23 .<br />

Page 6

Basic consumer protection mechanisms are needed as the financial sector<br />

evolves.<br />

In considering consumer protection, the UN Blue book (which marked the<br />

international year of micro-credit) distanced itself from the traditional caveat emptor<br />

(let the buyer beware) principle. According to the UN ‘this minimalist option is often<br />

considered anti-consumer 24 ’. The authors suggested that policy makers could opt<br />

to:<br />

• increase consumer information ( ‘truth in lending’ for example)<br />

• invest in financial literacy initiatives (ie consumer education)<br />

• insist that the retail financial industry take steps to protect consumers (self<br />

regulatory codes of conduct, for example)<br />

• enc<strong>our</strong>age the development of an independent regulatory oversight body<br />

responsible for monitoring, reviewing and taking complaints.<br />

Examples of recent practices in South Africa 25 :<br />

• Ending the practice of ‘card and PIN collection’, under which borrowers are<br />

forced to surrender ATM cards to lenders.<br />

• A Consumer Credit review, which led to a new National Credit Act, generally<br />

supported by CI member organisations in the country. There is also a new<br />

consumer credit regulator and a national credit register.<br />

• The huge growth in micro-lending during the 90s necessitated the re-<br />

regulation of the sector in 1999 under the Micro-Finance Regulatory Council,<br />

which became in effect a licensing body.<br />

Page 7

• 2004 saw the introduction of Mzansi basic banking for low income<br />

consumers, providing deposit services and ATM usage (but not credit) for<br />

reduced charges. There was no government subsidy. Within six weeks there<br />

were 180,000 users, far exceeding expectations. 90% of the new customers<br />

were previously unknown to the bank 26 .<br />

• The Financial Sector Charter committed banks to a major expansion of<br />

banking services.<br />

• There is a national ombudsman scheme and a National Consumer Tribunal<br />

that can mediate and act as an informal c<strong>our</strong>t in disputes over credit<br />

transactions. C<strong>our</strong>ts have the power to suspend a loan if it is thought to have<br />

been ‘reckless’ on the part of the lender. There is a countervailing duty of<br />

disclosure on the consumer to disclose all relevant information (such as<br />

outstanding debts) when applying for a loan.<br />

The state can take the initiative to improve banking services.<br />

This can be in the form of direct provision. For example postal banks exist in many<br />

countries, but ‘bricks and mortar’ networks are slow to develop and branches are<br />

often far from much of the population. The use of bank mandates for <strong>money</strong><br />

transfer by postal banks is declining and has virtually collapsed in parts of<br />

Francophone Africa 27 . Attempts are being made to introduce an electronic<br />

equivalent. Consumer education programmes can also be directed at children<br />

through national school curricula. CI member organisations across Africa are<br />

playing a key role in the development of materials and their dissemination to<br />

youngsters 28 .<br />

Page 8

The UN bluebook argued for state sponsorship over state provision. This could take<br />

the form of regulation (by credit bureaus, for example) to promote enhanced risk<br />

mitigation, and enhanced transparency, involving legislation along the lines of the<br />

South African example referred to above. The Ugandan government explicitly<br />

adopted an oversight (rather than a direct provision) role, after the failure of<br />

government run schemes in the late 90s 29 . Of c<strong>our</strong>se service providers do not<br />

simply have to rely on legislation to develop good practice.<br />

In Uganda, the Association of Microfinance Institutions has developed a code of<br />

practice for Consumer Protection with a focus on disclosure and financial<br />

education. It has been adopted by 42 MFIs and is a condition of entry to the<br />

association, thus providing a ‘badge’ of conduct to reassure consumers 30 .<br />

To avoid the mistakes of others, is there scope for a distinctively ‘African’<br />

approach to financial services for consumers?<br />

Africa has avoided the worst excesses of the financial services sector suffered in<br />

rich countries, precisely because the sector is relatively young. Only 17 countries in<br />

Africa have a stock market and their combined total fraction of global portfolio is<br />

1.81%, and African bank assets account for only 0.15% of the global total. Simon<br />

Heliso, writing in Global Future states: ‘The sophisticated evils unleashed by the<br />

sub-prime mortgage markets are simply absent.’ The South African banking sector<br />

has attracted praise for its recently elaborated regulatory structure, which has<br />

avoided many of the problems experienced in the North.<br />

Yet that does not insulate Africa from global economic trends, as trade has been<br />

badly affected by the recession. Capital markets in SSA fell by 30-40% between<br />

November 2007 and November 2008.<br />

Page 9

The global economic slowdown affects remittances sent home by Africans working<br />

abroad, which amount to about $10 billion annually. Those remittances must be<br />

vulnerable in the present climate as unemployment bites in rich countries 31 .<br />

Remittances are important both in and of themselves as a major support for<br />

families, and in terms of the incentives they have provided for technological<br />

evolution. Between 2000 and 2005, remittances to SSA increased by over 55%.<br />

Although lower in volume than aid and direct investment, they have proved to be<br />

less volatile and are often counter-cyclical, helping smooth over difficult times (such<br />

as seasonal problems for crop farmers). Furthermore, remittances can be saved to<br />

a very high degree – an IMF sponsored study found levels of remittance saving as<br />

high as 40% among families 32 .<br />

Traditionally only about one third of remittances go through formal channels,<br />

because even though migrants may have access to banks in the countries where<br />

they work, the recipient families may not. <strong>Consumers</strong> may be put off by high bank<br />

charges and high transfer charges by <strong>money</strong> transfer operators (MTOs). The<br />

market is heavily dominated by a few MTOs, notably Western Union, which has a<br />

market share of 65-100% in some countries in Francophone Africa 33 . Many<br />

communities in Francophone Africa rely on ‘porters’ of <strong>money</strong>, with the obvious<br />

risks that this entails, to carry sums for several families from, for example, a group<br />

of workers in France to a village in Mali.<br />

Some institutions have developed to meet the frustrated demand. Theba Bank, a<br />

miners’ bank, offers low cost transfers from South Africa to families in surrounding<br />

countries, such as Mozambique. The <strong>International</strong> Remittance Network of about<br />

200 credit unions offers low cost remittance services in many countries and does<br />

not require recipient families to have an account.<br />

Page 10

Sometimes remittances are grouped at village level and converted to local savings<br />

schemes to be used for house construction.<br />

Is <strong>money</strong> transfer by mobile phone the new magic bullet?<br />

Technology is accelerating access to <strong>money</strong> transfer and helping the informal to<br />

‘formalise’. Recently, telephone operators have started to help clients to send<br />

<strong>money</strong> home via text messages. If the receiving household does not have a bank<br />

account, then the remitted sum can be converted into a pre-paid debit card that can<br />

be used to make purchases. Alternatively, a line of credit can be opened at local<br />

stores with password protection operating through SMS. Thus the particular<br />

circumstances of African development – namely <strong>money</strong> transfers over long<br />

distances, lack of ‘bricks and mortar’ banking infrastructure but ready availability of<br />

mobile telephony – have led to the evolution of ‘branchless banking’, in which Africa<br />

is leading the way.<br />

For example, Safaricom in Kenya introduced M-Pesa in March 2007 with initial<br />

support from DFID’s Financial Deepening Challenge Fund. The service provides an<br />

SMS-based, low cost, person-to-person <strong>money</strong> transfer facility, which also allows<br />

the user to purchase prepaid goods and services (such as mobile top-up time and<br />

utilities). It has seen subscribers increase from around 100,000 at its launch to<br />

more than 7 million by August 2009. During that time M-Pesa has moved some 130<br />

billion Kenyan shillings ($1.7 billion). The average transaction is just over $20 but<br />

the volume has now risen to $2 million per day 34 . South Africa's MTN recently<br />

announced plans for a fully fledged bank account on mobile phones, with an<br />

optional credit card. The service will be extended to the 20 countries where MTN<br />

operates, including Uganda, Nigeria, Cameroon and Côte d'Ivoire, which combined<br />

have over 90 million mobile-phone users 35 .<br />

Page 11

The potential for such development in Africa is clearly huge, but there are<br />

limitations that should be taken into account. Mobile banking services have tended<br />

to be taken up by people with bank accounts as a convenient add-on service, and<br />

there is a risk of new monopolies developing.<br />

And of c<strong>our</strong>se the system will only be as comprehensive as the extent of the<br />

telephone network and transactions can fail due to system congestion at peak<br />

texting times 36 . While Kenya, South Africa and much of North Africa are<br />

approaching 100% mobile phone penetration, levels in Burundi, the Central African<br />

Republic, Eritrea, and Rwanda are less than 30% 37 . There are also issues around<br />

whether such services should be bank led (as in South Africa, where mobile phone<br />

companies have to form joint ventures with banks to provide mobile banking) or<br />

whether non-bank agents may take part, as in Kenya 38 . The root cause for<br />

optimism is that there are already about one billion people on the planet with a<br />

mobile phone but without a bank account 39 . In South Africa, for example, 48% of<br />

the population is ‘banked’, while mobile phone usage is 78%. In Kenya the figures<br />

are 10% and 20% respectively 40 .<br />

Towards universal access.<br />

Many of the approaches to financial services for poor consumers are common<br />

across continents. There are similarities in many of the recent innovations with<br />

developments in South Asia for example. Broad conclusions can be drawn for the<br />

poorer regions of the planet.<br />

However, different initiatives must be judged carefully on merit. Micro-credit, for<br />

example, should not be considered a magic bullet and has had to face the problem<br />

of costs remaining relatively fixed regardless of the size of the loan, meaning that<br />

charges for small amounts tend to be high.<br />

Page 12

According to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), MFIs are generally<br />

considered efficient when operating costs equal 12-15% of assets, while for banks<br />

this level would usually be around 5% 41 . Nevertheless, micro-finance is still<br />

normally significantly cheaper than the alternatives 42 .<br />

Given that it is still early days in terms of banking coverage for much of Africa,<br />

some basic strategic orientations could be adopted from the outset. CI have argued<br />

for the regulation of retail banking and investment banking as separate activities,<br />

even though they can be provided by the same banks. Retail banking can perhaps<br />

be viewed as a ‘public utility’ (not necessarily publicly owned but aimed at the<br />

general public), to be enc<strong>our</strong>aged through universal service programmes, which<br />

have been successfully applied in the telecoms sector.<br />

The argument for universal service to be fully integrated into future policy making is<br />

aptly articulated in the UN Blue Book:<br />

“We suggest that access to finance should be a central objective of prudential<br />

regulation and supervision...the two traditional goals of prudential regulation: safety<br />

of funds deposited in regulated financial institutions and the stability of the financial<br />

system as a whole, should be supplemented by a third goal: achieving universal<br />

access to financial services.”<br />

Page 13

Endnotes<br />

1. UN Blue Book Building Inclusive Financial Sectors for Development UN, 2006<br />

2. Ian McAuley Globalisation for all-reviving the spirit of Bretton Woods, an examination of<br />

developments in global financial markets <strong>Consumers</strong> <strong>International</strong>, 2003<br />

3. L Chen The protection of small savers in the Ugandan Micro-finance industry World<br />

Bank, 2000<br />

4. Nicholas Gyabaah, Ministry of Finance & Economic Planning (MoFEP) Ghana’s national<br />

strategy for financial literacy and CP in the micro-finance sector / Deogratias P Macha<br />

Developing a national financial literacy strategy – Tanzania Both MFW4A conference,<br />

Accra 2009<br />

5. Daryl Collins, Jonathan Murdoch, Stuart Rutherford, Orlanda Ruthven Portfolios of the<br />

Poor: How the World’s Poor Live on $2 a Day Financial Access Initiative, 2009.<br />

www.portfoliosofthepoor.com<br />

6. The Economist, 21 March 2009. L Chen op cit;<br />

7. Agence Francaise de Developpement Paroles d’acteurs (Key Players’ views) AFD, 2005<br />

8. Finmark Trust The savings market for the poor: assessing the barriers costs and<br />

potential January 2007<br />

9. The Economist, 21 March 2009.<br />

10. UN bluebook op cit<br />

11. Ignacio Mas Being able to make (small) deposits and payments, anywhere. Consultancy<br />

Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) Focus note no 45 April 2008 / Financial Sector<br />

Deepening Trust, Finscape National Survey on Access to and Demand for Financial<br />

Services in Tanzania. (2006 survey) Finscape e-book www.fsdt.or.tz / Gerda Piprek A<br />

national strategy in progress: Tanzania Macha op cit Both Accra 2009<br />

12. Leonard Mutesasira The microsave Africa experience World Bank, 2000<br />

13. The Economist, 21 March 2009.<br />

14. Mark Napier Finnmark Trust SA. Provision of Financial services in SA in Liberalisation &<br />

universal access to Basic services OECD, 2006.<br />

15. F Kariuki Financial education intervention – examples of Equity Bank Accra, 2009.<br />

16. Nancy Lee (CGAP) Social marketing and finance review. MFW4A Accra, 2009.<br />

17. Financing water for all Report of the World Panel on Financing Water Infrastructure,<br />

chaired by Michel Camdessus, report written by J. Winpenny; Word Water Council, et al<br />

World Water Forum 2003.<br />

Page 14

18. R Cardone & C Fonseca Financing and cost recovery IRC <strong>International</strong> Water &<br />

Sanitation Centre, 2003 / N.Shah et al: Financing of Water Supply & Sanitation Finance<br />

Policy Background Paper DFID, 2007.<br />

19. Meera Mehta Meeting the financing challenge for water supply & sanitation. Water &<br />

Sanitation Programme World Bank, 2003.<br />

20. Agence francaise de developpement op cit.<br />

21. Kariuki op cit<br />

22. Mutesasira op cit.<br />

23. Agence Francaise de developpement op cit<br />

24. UN Blue Book op cit<br />

25. M. Napier, Finmark Trust op cit; also ABSA Financial Health: you and the National<br />

Credit Act 2007<br />

26. Gautam Ivatury Using technology to build inclusive financial systems CGAP Focus note,<br />

32 January 2006.<br />

27. Agence francaise de developpement / Les operateurs de transferts formels.<br />

28. <strong>Our</strong> <strong>money</strong> <strong>our</strong> <strong>rights</strong>: How the global consumer movement is fighting for fair financial<br />

services <strong>Consumers</strong> <strong>International</strong>, 2010.<br />

29. E. Duflos & K Imboden The role of governments in micro-finance CGAP Donor brief no<br />

19, June 2004.<br />

30. David Baguma Concept note: Consumer Code of practice for micro-finance institutions;<br />

Association of Microfinance Institutions in Uganda AMFIU, Accra 2009<br />

31. Simon Heliso Africa: to integrate or to delink? in Global Future no 1, 2009<br />

32. S. Gupta, C. Pattillo & S. Wagh, Making remittances work for Africa in Finance &<br />

Development, June 2007 www.imf.org/fandd<br />

33. Agence Francaise de Developpement. Op cit<br />

34. O. Morawczynski & M. Pickens Poor people using mobile financial services:<br />

observations on Customer Usage and impact from M-PESA Focus note CGAP brief,<br />

August 2009.<br />

35. Louise Greenwood, Africa’s mobile revolution, BBC Africa business report, August 23<br />

2009.<br />

36. Morawczynski op cit.<br />

37. Greenwood op cit<br />

Page 15

38. Regulating transformational branchless banking: mobile phones and other technology to<br />

increase access to finance CGAP Focus note no 43, January 2008<br />

39. Greenwood, op cit.<br />

40. G Ivatury & I Mas The early experience with branchless banking CGAP Focus note No<br />

46, April 2008<br />

41. Ivatury CGAP 2006 op cit<br />

42. I Kota Microfinance: banking for the poor, Finance & Development June 2007<br />

www.imf.org/fandd<br />

<strong>Consumers</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

24 Highbury Crescent<br />

London N5 1RX<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Tel: +44 20 7226 6663<br />

Fax: +44 20 7354 0607<br />

www.consumersinternational.org<br />

www.consumidoresint.org<br />

Page 16<br />

<strong>Consumers</strong> <strong>International</strong> (CI) is the only independent global campaigning voice<br />

for consumers. With over 220 member organisations in 115 countries, we are<br />

building a powerful international consumer movement to help protect and<br />

empower consumers everywhere.<br />

<strong>Consumers</strong> <strong>International</strong> is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee,<br />

company number 4337865, and registered charity number 1122155.

![pkef]Qmf eg]sf] s] xf] < - Consumers International](https://img.yumpu.com/6479658/1/184x260/pkefqmf-egsf-s-xf-consumers-international.jpg?quality=85)