RECENT WORKS BY MALAQUIAS - Malaquias Montoya

RECENT WORKS BY MALAQUIAS - Malaquias Montoya

RECENT WORKS BY MALAQUIAS - Malaquias Montoya

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

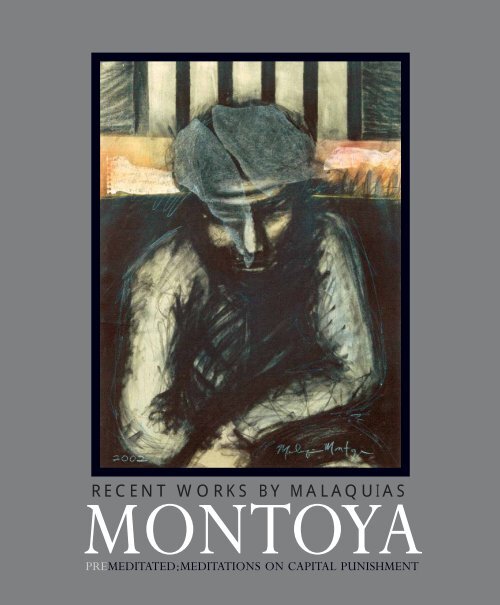

<strong>RECENT</strong> <strong>WORKS</strong> <strong>BY</strong> <strong>MALAQUIAS</strong>

PREMEDITATED :<br />

MEDITATIONS ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT<br />

<strong>RECENT</strong> <strong>WORKS</strong> <strong>BY</strong> <strong>MALAQUIAS</strong> MONTOYA<br />

An exhibition organized by the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame

For there to be equivalence, the death penalty would<br />

have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim<br />

of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death<br />

on him and who, from that moment onward, had<br />

confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster<br />

is not encountered in private life. 1<br />

Albert Camus<br />

3

4<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

<strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong> and Lezlie Salkowitz-<strong>Montoya</strong> gratefully acknowledge the generous contributions<br />

toward the publication of this catalogue. Major support has been provided by:<br />

Institute for Latino Studies<br />

Dr. Gilberto Cárdenas, Director<br />

Caroline Domingo, Publications Manager<br />

Snite Museum of Art<br />

Charles Loving, Director<br />

Gina Costa, Exhibit Curator<br />

University of Notre Dame<br />

The Center for Mexican American Studies<br />

Dr. José E. Limón, Director<br />

Dolores García, Assistant to the Director<br />

University of Texas @ Austin<br />

Ricardo and Harriet Romo<br />

San Antonio,Texas<br />

Special thanks to Carlos Jackson, MFA<br />

University of California, Davis,<br />

for the research conducted for this project<br />

Design, photography, and research: Lezlie Salkowitz-<strong>Montoya</strong><br />

Production: Jane Norton, Creative Solutions<br />

Printing: Harmony Marketing Group<br />

Co-published by <strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong> and Lezlie Salkowitz-<strong>Montoya</strong>, and the Institute for Latino Studies,<br />

University of Notre Dame.<br />

For ordering information contact either of the addresses below:<br />

Lezlie Salkowitz-<strong>Montoya</strong><br />

Post Office Box 6<br />

Elmira, CA 95625<br />

lsmontoya@earthlink.net<br />

www.malaquiasmontoya.com<br />

Cover image: The Killing of the Mentally Ill, 2002, Charcoal/Collage, 30x22 inches<br />

Chicana/o Studies Program<br />

Dr. Adela de la Torre, Director<br />

Committee on Research &<br />

Office of the Deans<br />

University of California, Davis<br />

The Chicano Studies Research Center<br />

Chon Noriega, Director<br />

University of California, Los Angeles<br />

Aztec America<br />

Carlos <strong>Montoya</strong>, President & CEO<br />

Chicago, Illinois<br />

Institute for Latino Studies<br />

250F McKenna Hall<br />

University of Notre Dame<br />

Notre Dame, IN 46556<br />

www.nd.edu/~latino/art<br />

© 2004 <strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong> and Lezlie Salkowitz-<strong>Montoya</strong><br />

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. No artwork from this book may be reproduced<br />

in any form whatsoever without written permission from the publishers.

Introduction<br />

Visual artist, poet and teacher, <strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong><br />

is one of an endangered species—a contemporary<br />

artist who believes that art can make the world<br />

a better place.<br />

<strong>Montoya</strong> is deeply ideological in the leadership<br />

role he fills for the Chicano Art Movement; he<br />

is iconoclastic, to American eyes, in his opposition<br />

to capitalism and imperialism; he is<br />

humanistic in his opposition to<br />

discrimination based on race, sex or<br />

class. Moreover, after lifelong<br />

devotion to “the cause,” he remains<br />

profoundly idealistic.<br />

Regardless of one’s politics, any thinking<br />

person has to admire an artist who has so<br />

selflessly “dedicated his life to informing<br />

and educating those neglected and<br />

exploited peoples whose lives are at risk in milieus of<br />

racism, sexism, and cultural oppression.” 2 In short, it<br />

is truly invigorating to find a contemporary artist<br />

who shares this institution’s belief that art can be the<br />

catalyst for positive change in individual lives.<br />

For all of these reasons it was a pleasure and an<br />

honor for the Snite Museum of Art, University of<br />

Notre Dame, to participate in the exhibition and<br />

publication of <strong>Montoya</strong>’s most recent body<br />

of work. We were especially grateful to be able<br />

to prepare this exhibition since <strong>Montoya</strong> seldom<br />

ventures into the mainstream American art<br />

system—namely, he does not produce his art<br />

for the purpose of selling, he does not exhibit<br />

in commercial galleries, and he is suspicious<br />

of museums.<br />

Premeditated: Meditations on Capital Punishment is the<br />

artist’s prolonged consideration of the death penalty<br />

What concerns me<br />

is, why do we kill,<br />

what happens to<br />

our humanity and<br />

to us, as a culture?<br />

-<strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong><br />

in America, as realized through the creation of<br />

a series of images depicting individuals being put to<br />

death.These images challenged faculty and students<br />

of Notre Dame, as indicated by their thoughts<br />

shared in the exhibition comment book. One<br />

student stated, “This exhibit struck me in<br />

a profound way. Indeed, our indifference to the<br />

systematic execution of our fellow human beings<br />

is a disturbing thing.” Another asked,<br />

“Where are the pictures of the victims<br />

of those portrayed here?”<br />

While <strong>Montoya</strong> promises to consider<br />

the plight of crime victims in future<br />

work, this exhibition focuses on those<br />

who are put to death as punishment for<br />

crimes they committed—or, possibly,<br />

did not commit. As such, it features<br />

important historical references. The<br />

Electrocution of William Kemmler (2002, charcoal)<br />

depicts the first person to be executed in the<br />

electric chair. The first attempt to kill Kemmler<br />

with a seventeen-second-charge of electric current<br />

was a failure. The severely–burnt Kemmler was in<br />

agony throughout the time required to recharge the<br />

chair. The second, successful attempt lasted over<br />

one minute, and several witnesses expressed<br />

revulsion at Kemmler’s moans of pain, the odor of<br />

burning flesh and the smoke emanating from his<br />

head. Ruth Snyder; First Woman Executed, Sing Sing<br />

Prison, 1928 (2002, acrylic painting) depicts two<br />

firsts. Not only was Snyder the first woman to be<br />

executed in the electric chair, but a newspaper<br />

photographer who had smuggled a camera onto the<br />

scene documented the event. The following day a<br />

photograph of the electrocution appeared on the<br />

front page of the Daily News. George Jackson Lives,<br />

Murdered in 1971 by San Quentin Prison Guards (1976,<br />

offset lithograph) depicts the killing of this Black<br />

5

6<br />

Panther, an event that was immortalized in Bob<br />

Dylan’s song “George Jackson.” Mumia Abu-Jamal<br />

(1999, charcoal/collage) celebrated a series of<br />

public events that occurred on September 11,<br />

1999, to protest the continued incarceration of<br />

Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has been on death row<br />

since 1982. Additional images depict more<br />

generic executions, lynchings, and hangings.<br />

The images are paintings, drawings, and silkscreen<br />

prints. Some have collage elements; others<br />

include texts from eyewitness accounts to<br />

executions or statements made by journalists and<br />

other writers. For example, Abolish the Death<br />

Penalty (2000, silkscreen) includes the following<br />

statement by Susan Blaustein, “We have perfected<br />

the art of institutional killing to the degree that it<br />

has deadened our natural, quintessentially human<br />

response to death.” The images are either black<br />

and white or they utilize strong, primary colors;<br />

the strokes are expressionistic, aggressive and<br />

gestural; drips suggest blood, vomitus, and other<br />

body fluids.<br />

In short, they are intentionally graphic—<br />

effectively designed products of the graphic arts<br />

and unpleasantly, vividly descriptive—designed<br />

to shock us out of the indifference described in<br />

Blaustein’s quote.<br />

Finally, and so typical of <strong>Montoya</strong>, proceeds from<br />

the sale of this catalog will benefit organizations<br />

opposed to the death penalty.<br />

Charles R. Loving<br />

Director and Curator of Sculpture<br />

Snite Museum of Art<br />

University of Notre Dame<br />

April 14, 2004<br />

Numerous studies…report that the death penalty<br />

has no deterrent effect.

Meditations on Capital Punishment<br />

by <strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong><br />

This project was conceived during the presidential<br />

election of 2000.There was a lot of media concentration<br />

on the state of Texas because our selected<br />

president was governor there. A great deal of<br />

attention was placed on the immense number<br />

of people being executed in that state’s death<br />

chambers. 3 I also started giving the death penalty<br />

a lot of consideration when I did the poster design<br />

for the Mumia 911 day. 4 The possibility of this<br />

brilliant man being murdered, on the<br />

basis of a flawed trial that left a lot of<br />

uncertainty behind his conviction, was<br />

hard to digest. 5<br />

I have always been against the death<br />

penalty. It is an irrational idea that you<br />

kill a person because s/he has killed<br />

another. It seems that the State,<br />

composed of intelligent people, could<br />

find another way of seeking justice;<br />

revenge seems too infantile a way of settling<br />

a dilemma. So how does the victim obtain justice? In<br />

a recent murder of a young woman and her unborn<br />

child, the victim’s mother said, “she hopes that<br />

whoever killed her daughter would hear her<br />

daughter’s pleas not to be killed for as long as he<br />

lives.” 6 Life imprisonment without parole would<br />

allow this torment to continue. For proponents of<br />

the death penalty, however, this punishment is too<br />

easy; there is no immediate satisfaction; it is<br />

anticlimactic after a long and agonizing trial, which<br />

kept us in daily suspense with headlines and TV<br />

news briefs. Death penalty proponents argue that<br />

life imprisonment would not be enough admonition<br />

to those preparing to murder; that those convicted<br />

must be killed in order to deter others from<br />

committing such heinous crimes. Numerous studies<br />

We create the<br />

situations that lead<br />

our children to<br />

commit monstrous<br />

acts, and then we<br />

kill them..<br />

though, conducted by various researchers, report<br />

that the death penalty has no deterrent effect. 7<br />

What concerns me is: Why do we kill and what<br />

happens to us as a humanity, as a culture? Why is<br />

state-sanctioned killing any different from a killing<br />

that takes place in the streets? One is planned and<br />

the other is not? Amadou Diallo, shot forty-one<br />

times by the NYPD, had no weapon, was innocent,<br />

and yet the police officers were set<br />

free. 8 I personally remember the<br />

young man, José Barlow Benavides,<br />

shot to death by Peace Officer Cogley<br />

in Oakland, CA.The investigation was<br />

futile—no one was charged for the<br />

crime. One must ask oneself, who lives<br />

and who dies?<br />

In August of 1945 the United States<br />

pulled off two incredible flybys<br />

awakening the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,<br />

killing and maiming hundreds of thousands of<br />

civilians, forever changing the global perspective<br />

of war and the balance of power. Eight years later,<br />

afraid of losing that power, our government killed<br />

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for alleged espionage.<br />

The sentencing judge stated, “By your betrayal, you<br />

have undoubtedly altered the course of history to<br />

the disadvantage of our country.” 9 Disadvantage? For<br />

years our government and its corporate backers<br />

have committed carnage against world citizens, and<br />

since World War II the great majority of these<br />

atrocities have been committed against people of<br />

color. South and Central America, the Caribbean,<br />

Asia, and the Middle East have all been playgrounds<br />

for testing our latest “killing technology” and flexing<br />

our imperial power.<br />

7

8<br />

This insensitivity to human life not only takes<br />

place on an international level but is also displayed<br />

in our own country. Our communities—the poor<br />

and people of color—are recipients of daily<br />

violence. Dilapidated schools, crumbling buildings,<br />

and service programs almost nonexistent due to<br />

cutbacks are a type of violence committed on the<br />

human psyche. Pain and violence are pervasive<br />

throughout poor communities as drugs flourish<br />

on street corners and police, ignorant and fearful,<br />

perpetuate further terror. Mothers, fathers,<br />

brothers and sisters are all walking around in<br />

a state of shock waiting for the next violent act.<br />

These poor communities are the victims of selfinflicted<br />

violence, and then to compound the<br />

We reap what we sow.<br />

situation, they feel they are to blame, not the<br />

greater structural mechanism. Our country’s<br />

solution to all of this is to build more prisons and<br />

increase the number on death row. 10 This act of<br />

concentrating the country’s poor into a cycle of<br />

economic and physical violence seems to be<br />

a purposeful act by the State. When billions and<br />

billions of dollars are spent on war and we refuse<br />

to educate our youth, house our homeless,<br />

provide medical care to our elderly and ill, and<br />

feed our hungry, one can only wonder what the<br />

real intentions are. We create the situations that<br />

lead our children to commit monstrous acts and<br />

then we kill them.<br />

Amadou Diallo, shot forty-one times in 1999 by the NYPD, had<br />

no weapon, was innocent, and yet the police officers were set free.<br />

Amadou Diallo, 2001<br />

Acrylic Painting

10<br />

George Jackson, a member of the Black Panthers, was jailed with<br />

a sentence of one year to life, ostensibly for stealing 70 dollars, and<br />

later killed in a San Quentin prison riot in 1971. Many believe that<br />

he was initially framed by the state in a racist response to his political<br />

activism and subsequently murdered by prison guards because of his<br />

attempts to organize his fellow inmates.<br />

After Jackson’s death, prison officials charged six prisoners—the so-<br />

called San Quentin Six—in a 97-count indictment. Charges ranged<br />

from attempted murder, conspiracy, escape, and assault to the killing<br />

of the prison guards and inmates.<br />

Their trial, at the time the longest in California history, lasted 17<br />

months. Four days each week the six, shackled and chained, were led<br />

into the Marin County Courthouse under heavy security. Eventually,<br />

three were acquitted and three were convicted of lesser charges. 11<br />

George Jackson Lives, 1976<br />

Offset Lithograph

12<br />

Luis Talamantez is a human rights activist and artist who speaks<br />

on the prison–industrial complex. A former political prisoner<br />

(one of the San Quentin Six whose trial gained international<br />

attention during the 1970s), Talamantez was acquitted and released<br />

in 1976. Drawing on his experiences of 30 years behind bars, he<br />

works to expose conditions at maximum security prisons like<br />

California’s infamous Pelican Bay, Corcoran State Prison, and Valley<br />

State Prison for Women.Talamantez is co-founder of California Prison<br />

Focus and currently pens a column for their publication. He has<br />

published two books of poetry and is an accomplished visual artist. 12<br />

Poem written and dedicated<br />

to <strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong><br />

at the opening of his preview<br />

exhibition at the Asian Resource<br />

Gallery, Oakland, CA.

How time flies…<br />

Our memories fade, and fall (on Silence)<br />

The Silence of<br />

Death Row—<br />

is a “thing alone” never to forget,<br />

—never to fall “Into”—<br />

Inspiration<br />

Reaches into the Dungeon Hole<br />

Creativity Comforts our “Waiting,”<br />

Our Silence<br />

until—<br />

the Final<br />

Scream—<br />

that Waits<br />

inside us.<br />

- Luis Talamantez, 2003<br />

13

14<br />

Mumia Abu-Jamal is an award-winning Pennsylvania journalist who<br />

exposed police violence against minority communities. On death<br />

row since 1982, he was wrongfully sentenced for the shooting<br />

of a police officer. New evidence, including the recantation of a key<br />

eyewitness, new ballistic and forensic evidence, and a confession from<br />

Arnold Beverly (one of the two killers of Officer Faulkner) points<br />

to his innocence. Mumia had no criminal record.<br />

For the last 21 years Abu-Jamal has been locked up 23 hours<br />

a day, been denied contact visits with his family, had his confidential<br />

legal mail illegally opened by prison authorities, and been put into<br />

punitive detention for writing his first of three books while in prison,<br />

Live from Death Row.<br />

His case is currently on appeal before the Federal District Court<br />

in Philadelphia. Mumia’s fight for a new trial has won the support<br />

of tens of thousands around the world. Mumia Abu-Jamal’s fate rests<br />

with all those people who believe in every person’s right to justice<br />

and a fair trial. 5<br />

Mumia Abu-Jamal, 1999<br />

Charcoal/Collage

16<br />

Lynching<br />

During the heyday of lynching, between 1889 and 1918, 3,224<br />

individuals were lynched, of whom 2,522 or 78 percent were Black.<br />

Typically, the victims were hung or burned to death by mobs of<br />

White vigilantes, frequently in front of thousands of spectators, many<br />

of whom would take pieces of the dead person’s body as souvenirs<br />

to help remember the spectacular event. 13<br />

Lynching Series 1, 2002<br />

Charcoal<br />

Overleaf:<br />

Lynching Series 2, 2002<br />

Silkscreen<br />

Lynching Series 3, 2002<br />

Silkscreen

20<br />

No matter what anyone may say about vengeance or deterrence,<br />

it is a matter of social control. 14<br />

- Joseph Ingle<br />

The five countries with the highest homicide rates that do not<br />

impose the death penalty average 21.6 murders per 100,000 people.<br />

The five countries with the highest homicide rate that do impose<br />

the death penalty average 41.6 murders for every 100,000 people. 15<br />

It’s a Matter of Social Control,<br />

2002<br />

Silkscreen

22<br />

Hanging<br />

Survival time: 8–13 minutes<br />

After the hanging, the sentenced loses consciousness almost<br />

immediately; the death occurs by asphyxiation, because of a slipknot<br />

put around the neck and fixed to a support by the other end. The<br />

weight of the body, hanging in mid-air or inclined forward, rests<br />

on the slipknot, determines its closing and the compressing action<br />

on respiratory tract. The hanging leaves different signs, both inside and<br />

outside the body: the sentenced becomes cyanotic, the tongue hangs<br />

out, the eyes pop out of his head, there is a groove on the neck;<br />

there are also vertebral lesions and internal fractures. 16 Three states,<br />

Delaware, New Hampshire, and Washington, currently provide for<br />

hanging as an option. Since 1977 three inmates have been executed<br />

by hanging: two in Washington, and the last, in 1996, in Delaware. 17<br />

The Hanging Series 1, 2002<br />

Charcoal/Pastel<br />

Overleaf:<br />

The Hanging Series 2, 2002<br />

Silkscreen<br />

The Hanging Series 3, 2002<br />

Silkscreen

26<br />

When in Gregg v. Georgia the Supreme Court gave its seal<br />

of approval to capital punishment, this endorsement was premised<br />

on the promise that capital punishment would be administered<br />

with fairness and justice. Instead, the promise has become a cruel<br />

and empty mockery. If not remedied, the scandalous state of our<br />

present system of capital punishment will cast a pall of shame over<br />

our society for years to come. We cannot let it continue.<br />

- Justice Thurgood Marshall, 1990 18<br />

Ruth Snyder, first woman<br />

executed, Sing Sing Prison 1928,<br />

2002 Acrylic Painting

28<br />

Electrocution<br />

In 1888 New York became the first state to adopt electrocution<br />

as its method of execution.William Kemmler was the first man<br />

executed by electrocution in 1890. Eventually twenty-six states<br />

adopted electrocution as a “clean, efficient, and humane” means of<br />

execution.Today, six states retain electrocution as their only method;<br />

five others offer it as an option. It is the second most common<br />

method of execution utilized in the modern era. 19<br />

The Electrocution<br />

of William Kemmler, 2002<br />

Charcoal

30<br />

The Electrocution of William Kemmler<br />

“Good-bye, William,” Durston said as he rapped<br />

twice on the door.<br />

Within the room, Davis sent the two-bell signal to<br />

the dynamo room. The voltage was increased,<br />

lighting the lamps on the control panel.Then Davis<br />

pulled down the switch that placed the electric<br />

chair into the circuit. The switch made<br />

a noise that could be heard in the execution<br />

chamber. Kemmler stiffened in the chair. The<br />

plan had been to leave the current on for a full<br />

20 seconds.<br />

Dr. Spitzka, who had stationed himself next to<br />

Kemmler in the room, watched Kemmler’s face<br />

and hands. At first they turned deadly pale but<br />

quickly changed to a dark red color.The fingers of<br />

the hand seemed to grasp the chair. The index<br />

finger of Kemmler’s right hand doubled up with<br />

such strength that the nail cut through the palm.<br />

There was a sudden convulsion as Kemmler strained<br />

against the straps and his face twitched slightly, but<br />

there was no sound from Kemmler’s lips.<br />

Dr. Spitzka held a stopwatch before him and<br />

counted the seconds while examining Kemmler.<br />

After just ten seconds had passed he shouted,<br />

“Stop!” which was echoed by other people in the<br />

room. Durston gave the order to the control<br />

room, and Davis pulled the lever back, switching<br />

the chair out of the circuit. The current had been<br />

on for just 17 seconds.<br />

Kemmler’s body, which had been straining against<br />

the straps, relaxed slightly when the current was<br />

turned off.<br />

“He’s dead,” said Spitzka to Durston as the<br />

witnesses who surrounded the chair congratulated<br />

each other.<br />

“Oh, he’s dead,” echoed Dr. MacDonald as the<br />

other witnesses nodded in agreement. Spitzka<br />

asked the other doctors to note the condition<br />

of Kemmler’s nose, which had changed to a bright<br />

red color. He then asked the attendants to loosen<br />

the face harness so he could examine the nose<br />

more closely. He then ordered that the body be<br />

taken to the hospital.<br />

“There is the culmination of ten years’ work and<br />

study,” exclaimed Southwick. “We live in a higher<br />

civilization from this day!”<br />

Durston, however, insisted that the body was not<br />

to be moved until the doctors signed the certificate<br />

of death.<br />

Dr. Balch, who was bending over the body looking<br />

at the skin, noticed a rupture on the right index<br />

finger of Kemmler’s right hand, where it had bent<br />

back into the base of his thumb, causing a small cut,<br />

which was dripping blood.<br />

“Dr. MacDonald,” said Balch, “see the rupture?”<br />

Spitzka then gave the order, “Turn on the current!<br />

Turn on the current instantly.This man is not dead!”<br />

Faces turned white, and the doctors fell back from<br />

the chair. Durston, who had been next to the chair,<br />

sprang back from the doorway and echoed<br />

Spitzka’s order to “turn on the current.”<br />

“Keep it on! Keep it on!” Durston ordered Davis.<br />

This was not as easy as it might have been.When he<br />

had been given the stop order, Davis had sent the<br />

message to the control room to turn off the<br />

dynamo. The voltmeter on the control panel was<br />

almost back to zero. Davis is sent the two-bell<br />

signal to the dynamo room and waited for the<br />

current to build up again.

The group of witnesses stood by horror-stricken, their<br />

eyes focused on Kemmler, as a frothy liquid began to drip<br />

from his mouth. Then his chest began to heave and a heavy<br />

sound like a groan came from his lips.Witnesses described<br />

it as “a heavy sound,” as if Kemmler was struggling to<br />

breathe. It continued at a regular interval, a wheezing<br />

sound that escaped Kemmler’s tightly clenched lips.<br />

The Human Experiment, 2003<br />

Silkscreen<br />

Durston continued to shout to the control room to turn on<br />

the current as some of the witnesses turned away from the<br />

chair, unable to bear the sight of Kemmler. Quinby was so<br />

sickened by the sight that he ran from the room. Another,<br />

unidentified, witness lay down on the floor. 20<br />

31

32<br />

Executions in the USA since 1976<br />

Amnesty International USA 21<br />

Updated Mar 28, 2004<br />

Total Cumulative<br />

Year Executions Total since 1976<br />

2004 18 903<br />

2003 65 885<br />

2002 71 820<br />

2001 66 749<br />

2000 85 683<br />

1999 98 598<br />

1998 68 500<br />

1997 74 432<br />

1996 45 358<br />

1995 56 313<br />

1994 31 257<br />

1993 38 226<br />

1992 31 188<br />

1991 14 157<br />

1990 23 143<br />

1989 16 120<br />

1988 11 104<br />

1987 25 93<br />

1986 18 68<br />

1985 18 50<br />

1984 21 32<br />

1983 5 11<br />

1982 2 6<br />

1981 1 4<br />

1980 0 3<br />

1979 2 3<br />

1978 0 1<br />

1977 1 1<br />

1976 0 0<br />

Failed Electrocution, 2002<br />

Charcoal

34<br />

The Killing of the Innocent<br />

“Marge, tell Mom not to bring any more cigarettes. My day<br />

of execution has been set for Friday the 3rd. Tell Mother I will<br />

soon be in the House of the Lord. He knows I am innocent.<br />

Marge, don’t bring Mom.”<br />

The Killing of the Innocent, 2002<br />

Acrylic Painting

36<br />

…Since we are guilty of no crime we will not be party to<br />

the nefarious plot to bear false witness against other innocent<br />

progressives to heighten hysteria in our land and worsen the<br />

prospects of peace in the world…<br />

…Nobody welcomes suffering, honey, but we are not the only<br />

ones who are going through hell because of all we stand for<br />

and I believe we are, in holding our own, contributing a share<br />

in doing away with the great sufferings of many others, both<br />

at this time and in time to come.<br />

- Letter from Julius to Ethel Rosenberg, May 3, 1953 22<br />

Executed, 2003<br />

Silkscreen

38<br />

Texas is the nation’s foremost executioner. It has been responsible for a third<br />

of the executions in the country and has carried out two and a half times as<br />

many death sentences as the next leading state. During the period when Texas<br />

rose to become the nation’s leading death penalty state, its crime rate grew by<br />

24 percent and its violent crime increased by 46 percent, much faster than the<br />

national average.Texas leads the country in numbers of its police officers killed,<br />

and more Texans die from gunshot wounds than from car accidents. 23<br />

The Gentle Sleep 1, 2002<br />

Charcoal

The Gentle Sleep 2, 2002<br />

Silkscreen<br />

His head pointed up, his body lay flat and still for seconds. Then a harsh<br />

rasping began. His fingers trembled up and down, and the witnesses standing<br />

near his midsection say that his stomach heaved. Quiet returned, and his head<br />

turned to the right, toward the black dividing rail. A second spasm of wheezing<br />

began. It was brief. His body moved no more. 24<br />

39

40<br />

Lethal Injection<br />

When the IV tubes are in place, a curtain may be drawn back from<br />

the window or one-way mirror to allow witnesses to view the<br />

execution. At this time, the inmate is given a chance to make a final<br />

statement, either written or verbal. This statement is recorded and<br />

later released to the media. The prisoner’s head is left unrestrained —<br />

in states that use regular windows, this enables the inmate to turn<br />

and look at the witnesses. In states that use one-way mirrors, the<br />

witnesses are shielded from view. 25<br />

A More Gentle Way of Killing...<br />

2003<br />

Silkscreen

42<br />

By using medical knowledge and personnel to kill people, we do<br />

more than undermine the emerging standards and procedures for<br />

good, ethical decision-making about the sick and dying. We also<br />

set off toward a terrifying land where the white gowns of physicians<br />

are covered by the black hoods of executioners. 26<br />

The Executioner, 2003<br />

Silkscreen

44<br />

The Killing of the Mentally Ill<br />

I remember very clearly the case of a mother watching her son<br />

with mental retardation standing trial for his life. One could see she<br />

had given a lot of thought to what she could do to comfort him,<br />

or to make some connection with this son who had such a low<br />

I.Q. Finally, the one thing she found to do all day was to give him<br />

a small candy bar. That at least, was something he could understand<br />

during his trial. 27<br />

The Killing of the Mentally Ill, 2002<br />

Charcoal/Collage

46<br />

We as a society are fed daily acts of violence.The legalized killing<br />

of another human being seems to satisfy our violent and vengeful<br />

impulses. We are becoming more grotesque than the most hideous<br />

crimes—and we have allowed it to happen.<br />

The Victim, 2003<br />

Silkscreen

48<br />

Racial minorities are being prosecuted under federal death penalty<br />

law far beyond their proportion in the general population or the<br />

population of criminal offenders. Analysis of prosecutions under<br />

the federal death penalty provisions of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of<br />

1988 reveals that 89 percent of the defendants selected for capital<br />

prosecution have been either African-American or Mexican-<br />

American…race continues to play an unacceptable part in the<br />

application of capital punishment in America today. 28<br />

Racial discrimination pervades the US death penalty at every stage<br />

of the process…There is only one way to eradicate ethnic bias, and<br />

the echoes of racism, from death penalty procedures in the United<br />

States—and this is by eradicating the death penalty itself. 29

We have perfected the art of institutional killing to the degree that<br />

it has deadened our natural, quintessentially human response to death. 30<br />

Abolish the Death Penalty, 2000<br />

Silkscreen<br />

49

Death Row Exonerations, 1973–2004<br />

Between 1973 and February 2004, 113 inmates on<br />

death row have been exonerated and freed.The most<br />

common reasons for wrongful convictions are mistaken<br />

eyewitness testimony, the false testimony of informants<br />

and “incentivized witnesses,” incompetent lawyers,<br />

defective or fraudulent scientific evidence, prosecutorial<br />

and police misconduct, and false confessions. In recent<br />

years, DNA played a role in overturning 12 of these<br />

wrongful death row convictions. 31

52<br />

Exhibition Tour<br />

Snite Museum of Art, Milly and Fritz Kaeser Mestrovic Studio Gallery, Notre Dame, IN. January11–February 22, 2004<br />

Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, Chicago, IL. August 20–November 14, 2004<br />

Julia C. Butridge Gallery, Dougherty Arts Center, Austin,TX. January 2005<br />

Instituto Mexicano, San Antonio,TX. February 2005<br />

Preview exhibition, Asian Resource Gallery, Oakland, CA. May–June, 2003<br />

The exhibition tour will continue during the next several years.<br />

Contact Lezlie Salkowitz-<strong>Montoya</strong>: 707-447-4194 or lsmontoya@earthlink.net regarding new bookings,<br />

tour schedules, and new venues.<br />

Works in the Exhibition<br />

Amadou Diallo, 2001<br />

Acrylic Painting, 51x42 inches<br />

George Jackson Lives, 1976<br />

Offset Lithograph, 22x17.5 inches<br />

Mumia Abu-Jamal, 1999<br />

Charcoal/Collage, 30x22 inches<br />

Lynching Series 1, 2002<br />

Charcoal, 24x18 inches<br />

Lynching Series 2, 2002<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

Lynching Series 3, 2002<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

It’s a Matter of Social Control, 2002<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

The Hanging Series 1, 2002<br />

Charcoal/Pastel 24x18 inches<br />

The Hanging Series 2, 2002<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

The Hanging Series 3, 2002<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

Ruth Snyder, first woman executed,<br />

Sing Sing Prison 1928, 2002<br />

Acrylic Painting, 55x51 inches<br />

The Electrocution of William Kemmler, 2002<br />

Charcoal, 24x18 inches<br />

The Human Experiment, 2003<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

Failed Electrocution, 2002<br />

Charcoal, 24x18 inches<br />

The Killing of the Innocent, 2002<br />

Acrylic Painting, 53x50 inches<br />

Executed, 2003<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

The Gentle Sleep 1, 2002<br />

Charcoal, 24x18 inches<br />

The Gentle Sleep 2, 2002<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

A More Gentle Way of Killing..., 2003<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

The Executioner, 2003<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

The Killing of the Mentally Ill, 2002<br />

Charcoal/Collage, 30x22 inches<br />

The Victim, 2003<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches<br />

Abolish the Death Penalty, 2000<br />

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

<strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong> is a<br />

leading figure in the<br />

Chicano graphic arts<br />

movement, a political and<br />

socially conscious movement<br />

that expresses itself<br />

primarily through the<br />

mass production of silkscreened<br />

posters. <strong>Montoya</strong>’s works include acrylic<br />

paintings, murals, washes, and drawings, but he is<br />

primarily known for his silkscreen prints, which<br />

have been exhibited both nationally and<br />

internationally. He is credited by historians as being<br />

one of the founders of the “social serigraphy”<br />

movement in the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-<br />

1960s. His visual expressions, art of protest, depict<br />

the struggle and strength of humanity and the<br />

necessity to unite behind that struggle. Like that of<br />

many Chicana/o artists of his generation, <strong>Montoya</strong>’s<br />

art is rooted in the tradition of the Taller de Gráfica<br />

Popular, the Mexican printmakers of the 1920s,<br />

’30s and ’40s, whose work expressed the need for<br />

social and political reform for the Mexican<br />

underprivileged. <strong>Montoya</strong>’s work uses powerful<br />

images, which are combined with text to create his<br />

socially critical messages.<br />

© Alan Pogue<br />

<strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong><br />

<strong>Montoya</strong> was raised in a family of seven children in<br />

the San Joaquin Valley, California, by parents who<br />

could not read or write. His father and mother were<br />

divorced when he was ten and his mother continued<br />

to work in the fields to support the four children<br />

still remaining at home so they could pursue their<br />

education. Since 1968 he has lectured and taught<br />

at numerous universities and colleges in the<br />

San Francisco Bay Area, including Stanford and<br />

the University of California, Berkeley. He was<br />

a professor at the California College of Arts and<br />

Crafts for twelve years, during five of which he was<br />

chair of the Ethnic Studies Department. As director<br />

of the Taller de Artes Gráficas in Oakland for five<br />

years, he produced various prints and conducted<br />

many community art workshops. <strong>Montoya</strong>,<br />

a visiting professor in the Art Department at the<br />

University of Notre Dame in 2000, continues as<br />

a Visiting Fellow of the Institute for Latino Studies,<br />

also at Notre Dame.<br />

Since 1989 <strong>Montoya</strong> has been a professor at the<br />

University of California, Davis. His classes, through<br />

the Departments of Chicana/o Studies and Art,<br />

include silkscreening, poster making, and mural<br />

painting, and focus on Chicana/o culture and history.<br />

This exhibition features recently created silkscreen<br />

images and paintings and related text panels dealing<br />

with the death penalty and penal institutions—<br />

inspired by the escalation of deaths at the hands of<br />

the State of Texas in recent years. <strong>Montoya</strong> has<br />

created images so powerful, so disturbing,<br />

so introspective, that viewers will not be able to<br />

examine them and walk away without feeling that<br />

they have witnessed an atrocity that has been<br />

committed in their names. As <strong>Montoya</strong> states,<br />

“I agree with journalist Susan Blaustein when she<br />

says that ‘we have perfected the art of institutional<br />

killing to the degree that it has deadened our<br />

natural, quintessentially human, response to death.’<br />

I want to produce a body of work depicting the<br />

horror of this act.” In these works <strong>Montoya</strong><br />

illuminates the inhumanity of the horrendous act<br />

of premeditated murder committed by the state—<br />

a situation where the use of punishment to<br />

discourage crime encourages criminality.<br />

Gina Costa<br />

Snite Museum of Art<br />

53

54<br />

References and Notes<br />

1. Albert Camus, Resistance, Rebellion, and Death (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1960), 199.<br />

2. Joseph Zirker, <strong>Malaquias</strong> <strong>Montoya</strong> (San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Art Institute, 1977), 10.<br />

3 Tom Brune, “Convention 2000 / The Republicans / George W. Bush’s Texas / Strong Backer of Death Penalty,” Newsday,<br />

August 3, 2000 (Washington Bureau, HighBeam Research, LLC).<br />

http://www.highbeam.com/library/doc0.asp?docid=1P1:30361052&refid=ink_d6&skeyword=&teaser=<br />

Texas Moratorium Network (TMN), an all-volunteer, grassroots organization formed in August 2000 with the primary goal<br />

of mobilizing statewide support for a moratorium on executions in Texas. http://texasmoratorium.org/?group=5<br />

Death Penalty Information Center, 1320 18 th Street NW, 5 th Floor,Washington DC 20036.<br />

http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/<br />

4. MUMIA 911:The Artists Network helped launch and organize the National Day of Art to Stop the Execution of Mumia<br />

Abu-Jamal, held on September 11, 1999, 305 Madison Ave. #1166, New York City, NY 10165.<br />

http://www.artistsnetwork.org/mumia/mumia911.html<br />

5. The Mobilization to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal, 298 Valencia St., San Francisco, CA 94103, 415-255-1085.<br />

http://www.freemumia.org/<br />

6. Cynthia McFadden, Mike Gudgell, Steffan Tubbs, and Taina Hernandez, contributors, “‘I Am Not Guilty’ Scott Peterson<br />

Pleads Not Guilty; Laci Peterson’s Family Vows Justice,” April 21, 2004, ABC News.<br />

http://abcnews.go.com/sections/us/SciTech/laci030421.html<br />

7. Hugo Adam Bedau, The Case against the Death Penalty (Washington, DC: Death Penalty Information Center and the American<br />

Civil Liberties Union OnLine Archives, copyright 1997, in English and Spanish).<br />

http://archive.aclu.org/library/case_against_death.html<br />

8. Frank Serpico, “Diallo Speaks to Serpico, Amadou’s Ghost,” The Village Voice, Features, March 8–14, 2000.<br />

http://www.villagevoice.com/issues/0010/serpico.php<br />

9. Walter & Miriam Schneir, Invitation to an Inquest (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company Inc., 1965), 1.<br />

10. Eve Goldberg and Linda Evans, “The Prison-Industrial Complex and the Global Economy,” posted at globalresearch.ca,<br />

October 18, 2001. http://globalresearch.ca/articles/EVA110A.html<br />

11. Walter Rodney, “George Jackson: Black Revolutionary,” World History Archives, November 1971.<br />

http:// www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/index-beb.html<br />

12. SPEAKOUT! Institute for Democratic Education and Culture, PO Box 99096, Emeryville, CA 94662, 510-601-0182.<br />

http://www.speakersandartists.org/<br />

13. Richard M. Perloff, “The Untold, Forgotten Story of the Press and the Lynching of African Americans,” Department<br />

of Communication, Cleveland State University, February 17, 2000.<br />

http://www.csuohio.edu/clevelandstater/Archives/Vol 1/Issue 13/news/news2.html<br />

14. Joseph Ingle, The Machinery of Death, a Shocking Indictment of Capital Punishment in the United States (New York: Amnesty<br />

International USA, 1995), 114.<br />

15. National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP), “The Death Penalty Has No Beneficial Effect on Murder Rates,”<br />

Fact Sheet: Deterrence. http://www.ncadp.org/fact_sheet5.html<br />

16. The Oracle Education Foundation, a California not-for-profit corporation, “When Life Generates Death (Legally),”<br />

ThinkQuest: Death Penalty. http://library.thinkquest.org/23685/data/hanging.html<br />

17. Florida Corrections Commission, 725 South Calhoun Street, Suite 109 Bloxham Building,Tallahassee, FL 32301.<br />

http://www.fcc.state.fl.us/

18. Justice Thurgood Marshall, speech delivered at the 1990 annual dinner in honor of the judiciary, American Bar<br />

Association, and quoted in the National Law Journal, Feb. 8, 1993. www.deathpenaltyinfo.org.<br />

19. Florida Corrections Commission. http://www.fcc.state.fl.us/<br />

20. Craig Brandon, The Electric Chair, an Unnatural American History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company<br />

Inc. Publishers, 1999), 176–77.<br />

21. Amnesty International USA, 322 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10001, “Executions in the USA since 76.”<br />

http://www.amnestyusa.org/abolish/listbyyear.do<br />

22. Walter and Miriam Schneir, Invitation to an Inquest, 233.<br />

23. Richard C. Dieter, “The Future of the Death Penalty in the US: A Texas-Sized Crisis,” Death Penalty Information<br />

Center, May 1994. http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?scid=45&did=489<br />

24. Amnesty International USA, “According to Witnesses...” http://www.amnestyusa.org/abolish<br />

25. Kevin Bonsor, “How Lethal Injection Works.” http://people.howstuffworks.com/lethal-injection.htm<br />

26. Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Who Owns Death? Capital Punishment, the American Conscience, and the End of<br />

Executions (New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.), 96.<br />

27. Ronald W. Conley, Ruth Luckasson, and George N. Bouthilet, The Criminal Justice System and Mental Retardation:<br />

Defendants and Victims (Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., 1992).<br />

28. Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights Committee on the Judiciary, “Racial Disparities in Federal Death<br />

Penalty Prosecutions 1988-1994,” Staff Report, One Hundred Third Congress, Second Session, March 1994.<br />

http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?scid=45&did=528<br />

29. Amnesty International, “Killing with Prejudice: Race and the Death Penalty in the USA,” May 1999.<br />

Quoted at http://www.amnestyusa.org/abolish/racialprejudices.html<br />

30. Susan Blaustein, “Witness to Another Execution,” Harpers Magazine, May 1994, p. 53.<br />

31. Alan Gell, “Death Row Exonerations, 1973–2004,” latest release recorded Feb. 18, 2004.<br />

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0908211/html<br />

An electronic version of this catalogue, with live links, can be viewed online at www.malaquiasmontoya.com and<br />

www.nd.edu/~latino/art.<br />

55

56<br />

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this catalogue will go to the following<br />

organizations actively working to abolish the death penalty.<br />

THE NATIONAL COALITION TO ABOLISH THE DEATH PENALTY provides information, advocates<br />

for public policy, and mobilizes and supports individuals and institutions that share our unconditional<br />

rejection of capital punishment. Our commitment to abolition of the death penalty is rooted in several<br />

critical concerns. First and foremost, the death penalty devalues all human life—eliminating the possibility<br />

for transformation of spirit that is intrinsic to humanity. Secondly, the death penalty is fallible and<br />

irrevocable—over one hundred people have been released from death row on grounds of innocence in<br />

this “modern era” of capital punishment.Thirdly, the death penalty continues to be tainted with race and<br />

class bias. It is overwhelming a punishment reserved for the poor (95 percent of the over 3,700 people<br />

under death sentence could not afford a private attorney) and for racial minorities (55 percent are people<br />

of color). Finally, the death penalty is a violation of our most fundamental human rights—indeed, the<br />

United States is the only western democracy that still uses the death penalty as a form of punishment.<br />

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty<br />

920 Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E.<br />

Washington, D.C. 20003<br />

202-543-9577<br />

www.ncadp.org<br />

CITIZENS UNITED AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY works to end the death penalty in the United<br />

States through aggressive campaigns of public education, and the promotion of tactical grassroots activism.<br />

Invigorated education involves the use of mass media to effectively communicate to the US public the<br />

message that the death penalty is bad public policy on economic, moral, and social grounds. To effect<br />

political change, alternatives to the death penalty must be made attractive to the majority of US voters.<br />

Mass public education must be reinforced at the grassroots level by local organizations and respected individuals.<br />

Politicians must be provided the support to lead on this issue, even in the face of unpopular public<br />

sentiment. CUADP is committed to act as a catalyst for continued development and implementation<br />

of a national grassroots strategy.<br />

Citizens United for Alternatives to the Death Penalty<br />

PMB 335<br />

2603 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Hwy<br />

Gainesville, FL 32609<br />

800-973-6548<br />

cuadp@cuadp.org<br />

JOURNEY OF HOPE...FROM VIOLENCE TO HEALING is an organization led by murder victim<br />

family members that conducts public education speaking tours and addresses alternatives to the death<br />

penalty. Journey “storytellers” come from all walks of life and represent the full spectrum and diversity<br />

of faith, color and economic situation. They are real people who know first hand the aftermath of the<br />

insanity and horror of murder.They recount their tragedies and their struggles to heal as a way of opening<br />

dialogue on the death penalty in schools, colleges, churches, and other venues.The Journey spotlights<br />

murder victims’ family members who choose not to seek revenge and instead select the path of love and<br />

compassion for all of humanity. Forgiveness is seen as a strength and as a way of healing. The greatest<br />

resources of the Journey are the people who are a part of it.<br />

Journey of Hope…From Violence to Healing, Inc.<br />

PO Box 210390<br />

Anchorage,AK 99521-0390<br />

877-9-24GIVE (4483)<br />

http://www.journeyofhope.org/

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this catalogue will go<br />

to organizations actively working to abolish the death penalty.