The Citron- Crested Cockatoo - Indonesian Parrot Project

The Citron- Crested Cockatoo - Indonesian Parrot Project

The Citron- Crested Cockatoo - Indonesian Parrot Project

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Citron</strong>- <strong>Crested</strong> <strong>Cockatoo</strong>s in the Wild: <strong>The</strong> Last Stand?<br />

Stewart Metz, MD<br />

Director, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Indonesian</strong> <strong>Parrot</strong> <strong>Project</strong> and PBW<br />

WHY IS IT IN DANGER?<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Citron</strong>-crested or Sumba cockatoo (or, technically, Cacatua sulphurea<br />

citronocristata) is physically the largest subspecies of Cacatua sulphurea,<br />

except possibly for the extraordinarily rare C.s. abbotti .In terms of numbers,<br />

it accounts for about half of the Yellow-crested cockatoos remaining in the<br />

wild , whereas there are less than 10 individuals of the abbotti race left on<br />

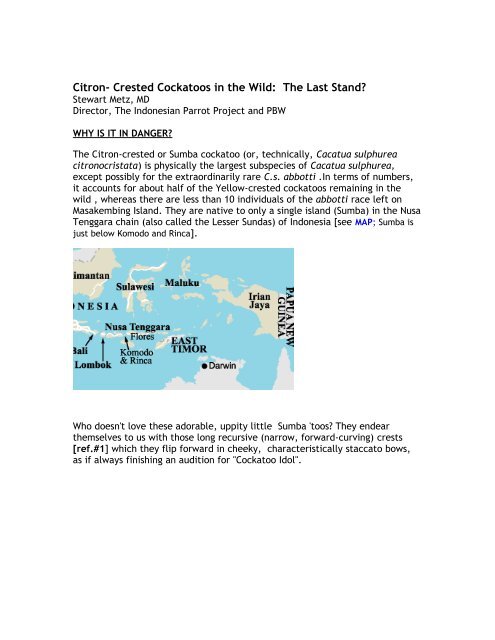

Masakembing Island. <strong>The</strong>y are native to only a single island (Sumba) in the Nusa<br />

Tenggara chain (also called the Lesser Sundas) of Indonesia [see MAP; Sumba is<br />

just below Komodo and Rinca].<br />

Who doesn't love these adorable, uppity little Sumba 'toos? <strong>The</strong>y endear<br />

themselves to us with those long recursive (narrow, forward-curving) crests<br />

[ref.#1] which they flip forward in cheeky, characteristically staccato bows,<br />

as if always finishing an audition for "<strong>Cockatoo</strong> Idol".

everybody loves them as pets.<br />

Unfortunately, that's the problem--<br />

First photo is of my own <strong>Citron</strong> 'Putri Cantik' which means "Beautiful Princess" in <strong>Indonesian</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> second photo, taken by Bonnie Zimmermann, is of a Sumba cockatoo confiscated from the<br />

illegal bird trade in government facilities on Ambon Island.<br />

If loss of habitat and the illegal pet bird trade wipes them out on Sumba, they<br />

will be lost from the wild forever. Sadly, both of these factors have existed<br />

side-by-side for many years on Sumba, reducing remaining number of cockatoos<br />

to critically endangered levels. This is despite a national domestic ban in their

trade since 1992 and a local (island) ban since 1996. In 2002, a single collector<br />

exported 52 cockatoos [Ref.#2].<br />

When I visited Sumba in 2002, I had some interesting discussions with<br />

trappers/ex-trappers. One was that the cockatoo appeared frequently in the<br />

mythology of Sumba and with some reverence, and is frequently depicted as<br />

bringing souls of the dead to heaven in the famous Sumba funeral weavings<br />

called ikat. Second, the cockatoo is the only bird which disperses the seeds of<br />

a tree (the name of which I could not get) which produces the wood used solely<br />

for holy/sacred buildings and which even illegal loggers will apparently not<br />

take. Nonetheless, this beautiful bird is still trapped.<br />

WHAT EXACLY IS THE MAGNITUDE OF THE DANGER?<br />

Sumba is a somewhat atypical island in that it is one of the driest in Indonesia,<br />

especially the Eastern part. Not only are large areas relatively arid, but as<br />

other areas were deforested, the damage was done piecemeal, tending to<br />

create forests islands. Since Sumba cockatoos prefer large blocks of<br />

undisturbed forest larger than 10 square kilometer, the concern is that<br />

cockatoos might be reluctant to fly large distances between such 'islands' even<br />

if they had to. <strong>The</strong>refore, several years ago, PBW/IPP funded the radiotelemetry<br />

studies of Dr. Margaret Kinnard which were able to demonstrate that<br />

showing that <strong>Citron</strong>s are very strong fliers (up to 32 km/day) and will cross at<br />

least 7 km. of open land to bridge these forest fragments [ref. #3].<br />

<strong>The</strong> figures for the rates of deforestation are frightening: In 1927, 55% of<br />

Sumba was covered by forest; in 1996 this figure had fallen to 13% and by 2000,<br />

to only 8%. <strong>The</strong>reby was lost trees critical for both nestbox creation and<br />

availability of preferred foods. Concomitantly, the population of cockatoos<br />

declined from more than 100 cockatoos per 1000 hectares in 1970, to about 13<br />

in 1980 to about 3 by 1990 and 2 by 2002, a stunning decline of 98 % in 32<br />

years! In terms of total populations, census studies in the 1990's suggested that<br />

only between 1150-2644 individuals existed on the island; it was reported in<br />

2002 that total island population might be relatively stable since 1992. When I<br />

visited there in 2002, I was only able to see 4 cockatoos, although a 6-month<br />

drought doubtless didn't help that figure. In 2004, the entire species of<br />

C.sulphurea was uplisted to Appendix I of CITES.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Sumba cockatoo is not the only bird to suffer under conditions of such<br />

marked deforestation. <strong>The</strong> Sumba Eclectus (Eclectus roratus cornelia) actually<br />

has a density [number of birds in a given area] as low as that of the cockatoo.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Sumba Great-billed <strong>Parrot</strong> Tanygnathus Megalorhynchos (see ref. #4 for<br />

details) and the endemic Sumba Hornbill Rhyticeros everetti are also in<br />

trouble. Interestingly these birds often nest together in the same tree, usually<br />

giant(> 35 meters) Tetrameles trees, a single one of which might contain<br />

multiple cockatoo nests, a few Eclectus nests, and a hornbill [Ref. #5]. Avian

condominiums on Sumba!! -- and even here, it's all about "Location, Location,<br />

Location".<br />

WHAT IS BEING DONE ABOUT IT?<br />

Two groups have systematically approach the plight of the <strong>Citron</strong>-crested<br />

cockatoo: the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS, based in the Bronx, N.Y.)<br />

and BirdLife-Indonesia (BL-I). PBW-the <strong>Indonesian</strong> <strong>Parrot</strong> <strong>Project</strong> has<br />

contributed to the efforts of both. <strong>The</strong> work by WCS was led by Dr. Margaret<br />

Kinnaird, and two post-doctoral students, Alexis Cahill and Jon Walker. One<br />

critical contribution was to carry out the radio-telemetry studies cited above,<br />

working with in collaboration with Dr.Nurul Winarni; another was to initiate<br />

work on a rehabilitation and release program for confiscated Sumba cockatoos<br />

(see details below).<br />

Alexis and Jon have also worked with Dr. Stuart Marsden to study the nesting<br />

and breeding ecology of the <strong>Citron</strong>-crested cockatoo, including the first studies<br />

of the use of artificial nest boxes. <strong>The</strong>se preliminary attempts were limited,<br />

however, both by occupancy of the nest boxes by other animals, and the ill<br />

effects of heavy rainfall.<br />

BirdLife Indonesia (BL-I) has had an extended presence on Sumba. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

program for the Sumba cockatoo specifically several 'prongs' to it:<br />

--- changing attitudes to make the cockatoo a symbol of their special heritage,<br />

and exploiting it as "anti-Sumba:<br />

Education for children<br />

Education for adults (One BL-I slogan on banners reads "Maukah anda<br />

dikurung seperti burung?" , which means "Do you want to be caged like a<br />

bird?")<br />

Appointing community <strong>Parrot</strong> Wardens and protection groups<br />

--- working to reduce illegal trade through anti-smuggling approaches<br />

---research<br />

---Rehabilitation and Release of Confiscated Sumba <strong>Cockatoo</strong>s. This program<br />

is funded by PBW/IPP. To date, the following initiatives have been<br />

accomplished:<br />

Trained government officers to improve handing of confiscated birds<br />

(2003)<br />

Paid for Bali vet to come to Sumba to train staff and develop standard<br />

procedures (2003)<br />

Coordinated with local communities, government and media (ongoing).<br />

Arrests of poachers have been made and jail sentences handed out (rare<br />

in Indonesia for bird smuggling), in large part due to information coming<br />

from local informants. As a result, 47% of local trappers and<br />

collectors are no longer active.<br />

Released first cockatoos (3) and Eclectus (4); August 21, 2003. As of<br />

2004, the total number of birds rehabilitated and released reached a

total of 13 (cockatoos, Eclectus and Green-naped lorikeets; breakdown<br />

not yet available). Dr. Kinnaird reported that " released<br />

birds[cockatoos] appeared to pair in the wild" (personal<br />

communication to S.M.; 5/24/2004).<br />

Last year, moved the rehabilitation center from town to a facility inside<br />

the forest of National Park and markedly expanded and upgraded entire<br />

facility.<br />

Photo is of the observation cage for <strong>Citron</strong>-crested cockatoos at the BirdLife rehabilitation<br />

and release facility on Sumba .It was taken prior to addition of accommodations for birds .©<br />

courtesy of Meivana Andryani, BirdLife Indonesia (reproduction only with permission)<br />

Three cockatoos are currently there being rehabilitated for possible release<br />

THE FUTURE<br />

Other good news is that two new national parks have been created on the<br />

island relatively recently: Manupeu-Tandaru and Laiwanggi-Wanggameti. To<br />

achieve success there, it was necessary to appreciate the practical significance<br />

to the major stakeholders (the local villagers, who are very poor) of removing<br />

from their use, major tracts of cultivatable land. Complicated agreements had<br />

to be worked out that were both ecologically- wise for conservation, but<br />

satisfactory to the community. [In contrast, many past efforts in other<br />

locations in the country were doomed to failure by simply decreeing the

expulsion of the local peoples from the national parks]. Such approaches are<br />

more likely to assure the long-term help of the community.<br />

We have just initiated talks with BirdLife to possibly broaden our collaboration<br />

and set up a joint PCR/DNA laboratory in Bogor to assay for viral and other<br />

diseases-- a step which we consider critical prior to releasing any psittacines<br />

back into the forest. This would involve also working with LIPI, the <strong>Indonesian</strong><br />

Institute of Science.<br />

So the good news is that there are a lot of people fighting now to make certain<br />

that this is NOT the last stand for kakatua kecil jambul kuning (the Little<br />

<strong>Cockatoo</strong> with the Yellow Crest).<br />

[1] In contrast, the recumbent crest of the Umbrella or Salmon-crested<br />

cockatoo is broader, fans out when opened, and lies flat: Carol Highfill, "Those<br />

magnificent cockatoo crests", available online at<br />

http://www.birdsnways.com/cockatoo/crests.htm<br />

(2) cited in Persulessy et al, Population Survey and Distribution of Cacatua<br />

sulphurea citronocristata. Report of Birdlife Indonesia. Bogor. 2003<br />

(3) Kinnaird, M., "<strong>Cockatoo</strong>s in Peril" PsittaScene. Vol 11, #2: May, 1999,<br />

pp. 11-13<br />

(4) Metz, S., Tindige, K. "Great-Billed <strong>Parrot</strong>s in Indonesia " PsittaScene<br />

15, #3: 2003, p.8<br />

(5) Marsden, SJ., "<strong>The</strong> Ecology and Conservation of the <strong>Parrot</strong>s of Sumba"<br />

PsittaScene. Vol 7, #2: May, 1995, pp. 8-9<br />

Stewart Metz<br />

July 12, 2006/ NFTF