VILDE FRANG, violin MICHAIL LIFITS, piano - San Francisco ...

VILDE FRANG, violin MICHAIL LIFITS, piano - San Francisco ...

VILDE FRANG, violin MICHAIL LIFITS, piano - San Francisco ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

presents<br />

<strong>VILDE</strong> <strong>FRANG</strong>, <strong>violin</strong><br />

<strong>MICHAIL</strong> <strong>LIFITS</strong>, <strong>piano</strong><br />

Friday, March 15, 2013, 8pm<br />

<strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong> Conservatory of Music Concert Hall<br />

MOZART Sonata No. 24 in F Major<br />

for Violin and Piano, K. 376<br />

Allegro<br />

Andante<br />

Rondo: Allegretto grazioso<br />

FAURÉ Sonata No. 1 in A Major<br />

for Violin and Piano, Opus 13<br />

Allegro molto<br />

Andante<br />

Allegro vivo<br />

Allegro quasi presto<br />

INTERMISSION<br />

BRAHMS Three Hungarian Dances for Violin and Piano<br />

from 21 Hungarian Dances for Piano, WoO 1<br />

(Arr. Joseph Joachim) No. 11 in D minor<br />

(Arr. Fritz Kreisler) No. 17 in F-sharp minor<br />

(Arr. Paul Klengel) No. 2 in D minor<br />

PROKOFIEV Sonata No. 2 in D Major<br />

for Violin and Piano, Opus 94<br />

Moderato<br />

Scherzo: Presto<br />

Andante<br />

Allegro con brio<br />

This recital is supported in part by a grant from The Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation.<br />

The Young Masters Series is supported in part by a generous gift from the estate<br />

of Maxine D. Wallace.<br />

Vilde Frang is represented by Opus 3 Artists, 470 Park Avenue South, 9th Floor North,<br />

New York, NY 10016 www.opus3artists.com<br />

Artist Profiles<br />

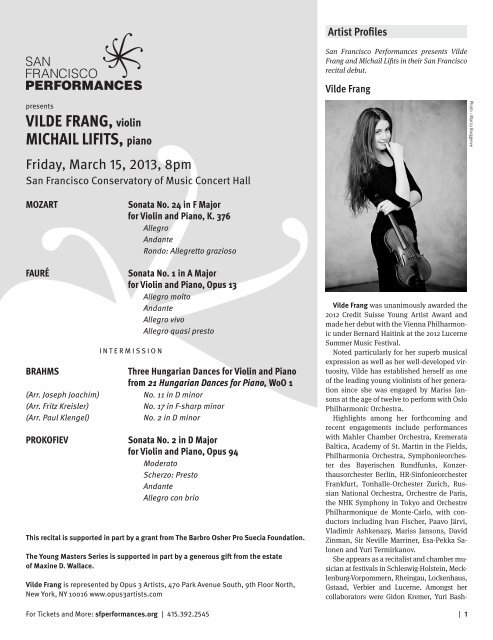

<strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong> Performances presents Vilde<br />

Frang and Michail Lifits in their <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong><br />

recital debut.<br />

Vilde Frang<br />

Vilde Frang was unanimously awarded the<br />

2012 Credit Suisse Young Artist Award and<br />

made her debut with the Vienna Philharmonic<br />

under Bernard Haitink at the 2012 Lucerne<br />

Summer Music Festival.<br />

Noted particularly for her superb musical<br />

expression as well as her well-developed virtuosity,<br />

Vilde has established herself as one<br />

of the leading young <strong>violin</strong>ists of her generation<br />

since she was engaged by Mariss Jansons<br />

at the age of twelve to perform with Oslo<br />

Philharmonic Orchestra.<br />

Highlights among her forthcoming and<br />

recent engagements include performances<br />

with Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Kremerata<br />

Baltica, Academy of St. Martin in the Fields,<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra, Symphonieorchester<br />

des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Konzerthausorchester<br />

Berlin, HR-Sinfonieorchester<br />

Frankfurt, Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich, Russian<br />

National Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris,<br />

the NHK Symphony in Tokyo and Orchestre<br />

Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo, with conductors<br />

including Ivan Fischer, Paavo Järvi,<br />

Vladimir Ashkenazy, Mariss Jansons, David<br />

Zinman, Sir Neville Marriner, Esa-Pekka Salonen<br />

and Yuri Termirkanov.<br />

She appears as a recitalist and chamber musician<br />

at festivals in Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern,<br />

Rheingau, Lockenhaus,<br />

Gstaad, Verbier and Lucerne. Amongst her<br />

collaborators were Gidon Kremer, Yuri Bash-<br />

For Tickets and More: sfperformances.org | 415.392.2545 | 1<br />

Photo : Marco Borggreve

Photo : Felix Broede<br />

met, Martha Argerich, Julian Rachlin, Leif Ove<br />

Andsnes, Sol Gabetta and Maxim Vengerov,<br />

and together with Anne-Sophie Mutter she has<br />

toured in Europe and the US, playing Bach’s<br />

Double Concerto with Camerata Salzburg.<br />

After her 2007 debut with London Philharmonic<br />

Orchestra, Vilde was re-engaged for a<br />

concert with the orchestra and Vladimir Jurowski<br />

at the Royal Festival Hall in the 2009<br />

season, followed by a recital at Wigmore<br />

Hall. Her concerto recording debut as EMI<br />

Classics’ Young Artist of the Year 2010 was<br />

greeted with acclaim by critics throughout<br />

the world and received the Edison Klassiek<br />

Award and a Classic BRIT Award for Best<br />

Newcomer. Her second disc, a recital recording<br />

with her duo partner Michail Lifits,<br />

received a Gramophone Award Nomination,<br />

Diapason Magazine’s “Diapason d‘Or” and<br />

the Echo Klassik Award. Her most recent release,<br />

featuring concertos by Tchaikovsky<br />

and Carl Nielsen, received the Deutsche<br />

Schallplattenpreis and was named Editor’s<br />

Choice by Gramophone Magazine.<br />

Born in 1986 in Norway, Vilde has studied<br />

at the Barratt Due Musikkinstitutt in Oslo,<br />

with Kolja Blacher at Musikhochschule Hamburg<br />

and Ana Chumachenco at the Kronberg<br />

Academy. She plays a Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume<br />

<strong>violin</strong> lent by the Anne-Sophie Mutter<br />

Freundeskreis Stiftung.<br />

Michail Lifits<br />

Michail Lifits, already compared to the legendary<br />

Wilhelm Kempff and praised for “his<br />

inspirational tone and his wise maturity”, as<br />

well as for “the breathtaking beauty of his<br />

playing”, has increasingly captured public<br />

attention since his debut at the age of 13 with<br />

Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto.<br />

Winner of the 57th Ferruccio Busoni International<br />

Piano Competition in Bolzano (2009),<br />

he had already collected first prizes in other international<br />

competitions in Italy and the USA,<br />

such as Pianello val Tidone (2003), Treviso<br />

(2004), Monza (2006) and Hilton Head (2009).<br />

Solo engagements have brought Michail<br />

Lifits to Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall<br />

and Lincoln Center in New York, the Auditorium<br />

du Louvre in Paris, to the Teatro della<br />

Pergola in Florence, the NCPA in Beijing,<br />

the Tonhalle in Zurich and the Sala Verdi in<br />

Milan. He is a regular guest at international<br />

festivals in France, Germany, Poland, Italy<br />

and the United States, including the Festival<br />

d’Auvers-sur-Oise, the Annecy Festival, the<br />

Kissinger Sommer, Rheingau Music Festival,<br />

the Ruhr Piano Festival, Festspiele Mecklenburg-Vorpommern<br />

and the Chopin Festival in<br />

Duzhniki Zdroj. Among his appearances with<br />

Orchestra he has played with the Hilton Head<br />

Symphony, the Thüringen Philharmonie<br />

Gotha, the Orchestra del Teatro Verdi di Trieste<br />

and the Orchestra Sinfonica Siciliana in<br />

Palermo. In 2011 he made his debut with the<br />

Deutsche Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (DSO).<br />

The same year saw his debut in London’s<br />

Wigmore Hall, in the `Keyboard Trust Prizewinners<br />

Series’ which exhibits the cream of this international<br />

foundation’s new talent. Critics described<br />

his performance as “Perfection itself.”<br />

Since 2011, Michail Lifits has been under contract<br />

with the classical label DECCA/Universal<br />

Classics. In 2012 DECCA released his debut CD<br />

dedicated to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.<br />

Michail Lifits was born in 1982 in Tashkent,<br />

Uzbekistan. He studied with Karl-Heinz Kammerling<br />

and Bernd Goetzke at the University<br />

for Music and Drama in Hanover and with<br />

Boris Petrushansky at the International Piano<br />

Academy Incontri col Maestro in Imola (Italy).<br />

Program Notes<br />

Sonata No. 24 in F Major<br />

for Violin and Piano, K. 376<br />

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart<br />

Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg<br />

Died December 5, 1791, Vienna<br />

In June 1781, at the age of 25, Mozart broke<br />

away from the two authority figures in his<br />

life—his father and Archbishop Colloredo of<br />

Salzburg—and set out to establish himself in<br />

Vienna. His first task was to make himself<br />

financially independent, and to that end he<br />

took students and performed widely in Vienna.<br />

But Mozart wished to succeed as a composer,<br />

and the sources of income for a composer<br />

were more complex. A composer could<br />

make significant income from an opera commission,<br />

but Mozart was also aware of a quite<br />

different market: the increasing number of<br />

amateur musicians in Vienna who needed<br />

music to perform. His first publication in Vienna<br />

was written not on commission from a<br />

member of the nobility but for talented amateur<br />

performers: during the summer of 1781,<br />

while he was at work on The Abduction from<br />

the Seraglio, Mozart wrote four sonatas for<br />

keyboard and <strong>violin</strong>, combined them with<br />

two sonatas written earlier, and published<br />

the set that November as his Opus 2.<br />

These six sonatas attracted immediate attention,<br />

and one early reviewer wrote about<br />

them at length: “These sonatas are the only<br />

ones of this kind. Rich in new ideas and in<br />

evidences of the great musical genius of their<br />

author. Very brilliant and suited to the instrument.<br />

At the same time the accompaniment<br />

of the <strong>violin</strong> is so artfully combined with the<br />

clavier part that both instruments are kept<br />

constantly on the alert; so that these sonatas<br />

require just as skillful a player on the <strong>violin</strong><br />

as on the clavier.” This reviewer makes at an<br />

important point. Earlier sonatas for this combination<br />

of instruments had essentially been<br />

keyboard sonatas with the accompaniment<br />

of <strong>violin</strong>, and in fact Mozart’s description<br />

on the title page of the new set seems to preserve<br />

that identity: “Six Sonatas for Clavier<br />

or Pianoforte, with the Accompaniment of<br />

a Violin.” The reviewer, however, notes that<br />

these are in fact duo-sonatas (“the only ones<br />

of this kind”) and that the musical duties are<br />

divided evenly here (“require just as skillful<br />

a player on the <strong>violin</strong> as on the clavier”). The<br />

<strong>piano</strong> may retain a measure of primacy in<br />

these sonatas, but Mozart is well on his ways<br />

to re-defining the <strong>violin</strong> sonata and giving<br />

the <strong>violin</strong> a much more important role.<br />

The Allegro opens with three bright chords,<br />

and the whole movement is characterized by<br />

energy and thrust. The <strong>piano</strong> introduces the<br />

more restrained second idea, and all seems<br />

set for a standard sonata-form movement,<br />

but Mozart springs a surprise at the development.<br />

Rather than developing these themes,<br />

he instead seizes on a brief turn-figure from<br />

the end of the exposition and builds the development<br />

on this. He brings back his principal<br />

themes in the recapitulation and closes<br />

the movement out quietly on the turn-figure.<br />

The Andante is remarkable for the range of<br />

its sounds, for it seems in constant, murmuring<br />

motion. Some of this is the sound of<br />

quietly-pulsing sixteenths that runs through<br />

the accompaniment, but Mozart also has<br />

both instruments trilling at length here. The<br />

concluding Rondo gets off to an elegant start<br />

(Mozart’s marking grazioso is exactly right),<br />

but this attractive tune is interrupted by a<br />

number of varied and substantial episodes<br />

2 | For Tickets and More: sfperformances.org | 415.392.2545

efore the movement makes its way to the<br />

nicely-understated close.<br />

Violin Sonata in A Major, Opus 13<br />

Gabriel Fauré<br />

Born May 13, 1845, Pamiers<br />

Died November 4, 1924, Paris<br />

One of Fauré’s students, the composer Florent<br />

Schmitt, described his teacher as an “unintentional,<br />

unwitting revolutionary.” The<br />

term “revolutionary” hardly seems to apply<br />

to a composer best-known for his gentle Requiem,<br />

songs, and chamber works. But while<br />

Fauré was no heaven-storming radical bent<br />

on undoing the past, his seemingly-quiet<br />

music reveals enough rhythmic, harmonic,<br />

and melodic surprises to justify Schmitt’s<br />

claim. The Violin Sonata in A Major, written<br />

in the summer of 1876 while Fauré was vacationing<br />

in Normandy, is dedicated to his<br />

friend, the <strong>violin</strong>ist Paul Viardot. Following<br />

its first performance, the sonata was praised<br />

by Fauré’s teacher Saint-Saëns for its “formal<br />

novelty, quest, refinement of modulation, curious<br />

sonorities, use of the most unexpected<br />

rhythms…charm [and]…the most unexpected<br />

touches of boldness.” This is strong praise,<br />

but close examination of the sonata shows<br />

that Saint-Saëns was right.<br />

One of the most interesting features of the<br />

opening Allegro molto occurs in the accompaniment,<br />

which is awash in a constant flow of<br />

eighth-notes. The first theme appears immediately<br />

in the <strong>piano</strong>, and already that instrument<br />

is weaving the filigree of accompanying<br />

eighth-notes that will shimmer throughout<br />

this movement: one of the challenges for performers<br />

is to provide tonal variety within this<br />

continual rustle of sound. The movement is<br />

in sonata form, and the descending second<br />

theme, introduced by the <strong>violin</strong>, is accompanied<br />

by a murmur of triplets from the <strong>piano</strong>.<br />

The movement concludes on a fiery restatement<br />

of the opening theme.<br />

Distinguishing the Andante is its rhythmic<br />

pulse: a 9/8 meter throbs throughout the<br />

movement, though Fauré varies its effect by<br />

syncopating the accents within the measure.<br />

The third movement, a scherzo marked Allegro<br />

vivo, goes like a rocket. Fauré chooses<br />

not the expected triple meter of the traditional<br />

scherzo but a time signature of 2/8, an<br />

extremely short rhythmic unit, particularly<br />

when his metronome marking asks for 152<br />

quarter-notes per minute. He further complicates<br />

the rhythm by writing in quite short<br />

phrases, so that the effect is of short phrases<br />

rapidly spit out, then syncopated by sharp<br />

off-beats. A lovely, graceful trio gives way to<br />

the opening material, and the movement suddenly<br />

vanishes in a shower of pizzicato notes.<br />

The tempo marking for the finale—Allegro<br />

quasi presto—seems to suggest a movement<br />

similar to the third, but despite its rapid tempo<br />

the last movement flows easily and majestically.<br />

Or at least it seems to, for here Fauré<br />

complicates matters harmonically. The <strong>piano</strong><br />

opens in the home key—A major—but the<br />

<strong>violin</strong> seems always to prefer that key’s relative<br />

minor, F-sharp minor, and the resulting<br />

harmonic uncertainty continues throughout<br />

the movement until the sonata ends in unequivocal<br />

A major.<br />

To emphasize this sonata’s originality may<br />

have the unhappy effect of making the music<br />

sound cerebral, interesting only for its technical<br />

novelty. That is hardly the case. Fauré’s<br />

Sonata in A Major is one of the loveliest <strong>violin</strong><br />

sonatas of the late nineteenth century, full of<br />

melodic, graceful, and haunting music.<br />

Hungarian Dances<br />

No. 2 in D minor<br />

No. 11 in D minor<br />

No. 17 in F-sharp minor<br />

Johannes Brahms<br />

Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg<br />

Died April 3, 1897, Vienna<br />

Brahms had a life-long fascination with<br />

Hungarian music, which for him meant<br />

gypsy music. As a boy in Hamburg, he first<br />

encountered it from the refugees fleeing revolutions<br />

in Hungary for a new life in America,<br />

and he was introduced to gypsy fiddle tunes<br />

at the age of 20 while on tour with the Hungarian<br />

<strong>violin</strong>ist Eduard Reményi (it was on<br />

that tour that Brahms began his lifelong<br />

collection of Hungarian folk-tunes). Over a<br />

period of years, he wrote a number of what<br />

he called Hungarian Dances for <strong>piano</strong> fourhands<br />

and played them for (and with) his<br />

friends. He published ten of these in 1869<br />

and another eleven in 1880, and they proved<br />

a huge success. There was a ready market<br />

for this sort of music that could be played at<br />

home by talented amateurs, and these fiery,<br />

fun pieces carried Brahms’ name around the<br />

world (they also inspired the Slavonic Dances<br />

of his friend Antonín Dvořák)<br />

In the Hungarian Dances, Brahms took<br />

csardas tunes and–preserving their themes<br />

and characteristic freedom–wrote his own<br />

music based on them. To his publisher,<br />

Brahms described these dances as “genuine<br />

gypsy children, which I did not beget, but<br />

merely brought up with bread and milk.” It<br />

has been pointed out, however, that Brahms<br />

did not begin with authentic peasant tunes<br />

(which Bartók and Kodály would track down<br />

in the twentieth century), but with those<br />

tunes as they had been spiffed-up for popular<br />

consumption by the “gypsy” bands that<br />

played in the cafés and on the streetcorners<br />

of Vienna. Brahms would not have cared<br />

about authenticity. He loved these tunes–<br />

with their fiery melodies, quick shifts of<br />

mood, and rhythmic freedom–and he successfully<br />

assimilated that style, particularly<br />

its atmosphere of wild gypsy fiddling (in fact,<br />

he assimilated it so successfully that several<br />

of the Hungarian Dances are based on “gypsy”<br />

tunes that he composed himself).<br />

This concert offers three of Brahms’ Hungarian<br />

Dances. Program notes for the individual<br />

dances would be a form of intellectual<br />

overkill. Sit back, enjoy this fiery music, and<br />

sense why Brahms loved it as much as he did.<br />

Sonata No. 2 in D Major<br />

for Violin and Piano, Opus 94<br />

Serge Prokofiev<br />

Born April 23, 1891, Sontsovka<br />

Died March 5, 1953, Moscow<br />

This sonata, probably the most popular<br />

<strong>violin</strong> sonata composed in the twentieth century,<br />

was originally written for the flute. But<br />

when David Oistrakh heard the premiere on<br />

December 7, 1943, he immediately suggested<br />

to the composer that it was ideal music for<br />

the <strong>violin</strong>. Together, composer and <strong>violin</strong>ist<br />

prepared a version for <strong>violin</strong> and <strong>piano</strong>,<br />

and Oistrakh gave the first performance of<br />

this version on June 17, 1944. The music remains<br />

very much the same (the <strong>piano</strong> part is<br />

identical in both versions), but Prokofiev altered<br />

several passages to eliminate awkward<br />

string crossings for the <strong>violin</strong>ist and added<br />

certain <strong>violin</strong>istic features impossible on the<br />

flute: pizzicatos, doublestops, harmonics.<br />

Ironically, the <strong>violin</strong> version–which profits<br />

enormously from the flexibility and range of<br />

sound of the <strong>violin</strong>–has become much more<br />

popular than the original.<br />

In contrast to the bleak First Violin Sonata<br />

(which the composer said should sound “like<br />

wind in a graveyard”), the Second Sonata is<br />

one of Prokofiev’s sunniest compositions.<br />

There is no hint in this music of the war raging<br />

in Russia at this time, none of the pain<br />

that runs through the earlier sonata. The<br />

third movement is quietly wistful and the<br />

music is full of Prokofiev’s characteristically<br />

pungent harmonies, but the sonata is generally<br />

serene, a retreat from the war rather than<br />

its mirror.<br />

continued on page 4<br />

For Tickets and More: sfperformances.org | 415.392.2545 | 3

Frang Notes continued from page 3<br />

The sonata is in the four-movement slowfast-slow-fast<br />

sequence of the baroque sonata.<br />

The opening Moderato, in sonata form,<br />

begins with a beautifully poised melody for<br />

the <strong>violin</strong>, a theme of classical purity. The<br />

<strong>violin</strong> also has the second subject, a singing<br />

dotted melody. Prokofiev calls for an exposition<br />

repeat, and the vigorous development<br />

leads to a quiet close on a very high restatement<br />

of the opening idea.<br />

The Presto sounds so brilliant and idiomatic<br />

on the <strong>violin</strong> that it is hard to imagine<br />

that it was not conceived originally for that in-<br />

strument. This movement was in fact marked<br />

Allegretto scherzando in the flute version,<br />

but—taking advantage of the <strong>violin</strong>’s greater<br />

maneuverability—Prokofiev increased the<br />

tempo to Presto in the <strong>violin</strong> version, making<br />

it a much more brilliant movement. It falls<br />

into the classical scherzo-and-trio pattern,<br />

with two blazing themes in the scherzo and<br />

a wistful melody in the trio. The end of this<br />

movement, with the <strong>violin</strong> driving toward the<br />

climactic pizzicato chord, is much more effective<br />

in the <strong>violin</strong> version than in the original.<br />

The mood changes markedly at the Andante,<br />

which is a continuous flow of melody<br />

on the opening <strong>violin</strong> theme. The <strong>violin</strong> part<br />

becomes more elaborate as the movement<br />

progresses, but the quiet close returns to the<br />

mood of the beginning. The Allegro con brio<br />

finale is full of snap and drive, with the <strong>violin</strong><br />

leaping throughout its range. At the center<br />

of this movement, over steady <strong>piano</strong> accompaniment,<br />

Prokofiev gives the <strong>violin</strong> one of<br />

those bittersweet melodies so characteristic<br />

of his best music. Gradually the music quickens,<br />

returns to the opening tempo, and the<br />

sonata flies to its resounding close.<br />

—Program notes by Eric Bromberger<br />

4 | For Tickets and More: sfperformances.org | 415.392.2545