You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

HenrYk szerYng<br />

greaT violinisTs Part 2<br />

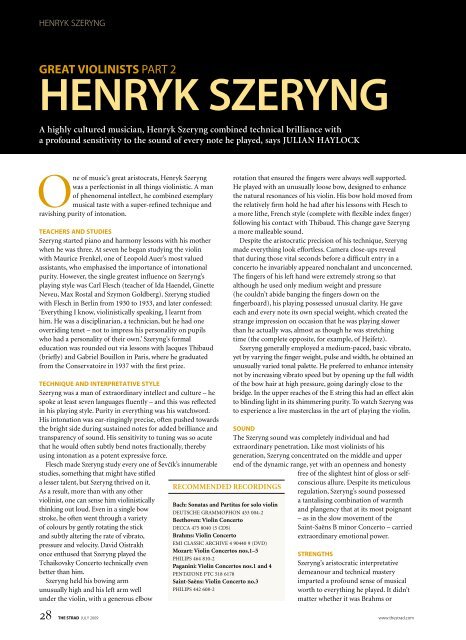

<strong>Henryk</strong> <strong>Szeryng</strong><br />

A highly cultured musician, <strong>Henryk</strong> <strong>Szeryng</strong> combined technical brilliance with<br />

a profound sensitivity to the sound of every note he played, says JuliAn HAylock<br />

One of music’s great aristocrats, <strong>Henryk</strong> <strong>Szeryng</strong><br />

was a perfectionist in all things violinistic. A man<br />

of phenomenal intellect, he combined exemplary<br />

musical taste with a super-refined technique and<br />

ravishing purity of intonation.<br />

Teachers and sTudies<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> started piano and harmony lessons with his mother<br />

when he was three. At seven he began studying the violin<br />

with Maurice Frenkel, one of Leopold Auer’s most valued<br />

assistants, who emphasised the importance of intonational<br />

purity. However, the single greatest influence on <strong>Szeryng</strong>’s<br />

playing style was Carl Flesch (teacher of Ida Haendel, Ginette<br />

Neveu, Max Rostal and Szymon Goldberg). <strong>Szeryng</strong> studied<br />

with Flesch in Berlin from 1930 to 1933, and later confessed:<br />

‘Everything I know, violinistically speaking, I learnt from<br />

him. He was a disciplinarian, a technician, but he had one<br />

overriding tenet – not to impress his personality on pupils<br />

who had a personality of their own.’ <strong>Szeryng</strong>’s formal<br />

education was rounded out via lessons with Jacques Thibaud<br />

(briefly) and Gabriel Bouillon in Paris, where he graduated<br />

from the Conservatoire in 1937 with the first prize.<br />

Technique and inTerpreTaTive sTyle<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> was a man of extraordinary intellect and culture – he<br />

spoke at least seven languages fluently – and this was reflected<br />

in his playing style. Purity in everything was his watchword.<br />

His intonation was ear-ringingly precise, often pushed towards<br />

the bright side during sustained notes for added brilliance and<br />

transparency of sound. His sensitivity to tuning was so acute<br />

that he would often subtly bend notes fractionally, thereby<br />

using intonation as a potent expressive force.<br />

Flesch made <strong>Szeryng</strong> study every one of Ševčík’s innumerable<br />

studies, something that might have stifled<br />

a lesser talent, but <strong>Szeryng</strong> thrived on it.<br />

As a result, more than with any other<br />

violinist, one can sense him violinistically<br />

thinking out loud. Even in a single bow<br />

stroke, he often went through a variety<br />

of colours by gently rotating the stick<br />

and subtly altering the rate of vibrato,<br />

pressure and velocity. David Oistrakh<br />

once enthused that <strong>Szeryng</strong> played the<br />

Tchaikovsky Concerto technically even<br />

better than him.<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> held his bowing arm<br />

unusually high and his left arm well<br />

under the violin, with a generous elbow<br />

reCoMMended reCordingS<br />

Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin<br />

DEuTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 453 004-2<br />

Beethoven: Violin Concerto<br />

DECCA 475 8040 (5 CDS)<br />

Brahms: Violin Concerto<br />

EMI CLASSIC ARCHIvE 4 90440 9 (DvD)<br />

Mozart: Violin Concertos nos.1–5<br />

PHILIPS 464 810-2<br />

Paganini: Violin Concertos nos.1 and 4<br />

PENTATONE PTC 518 6178<br />

Saint-Saëns: Violin Concerto no.3<br />

PHILIPS 442 608-2<br />

rotation that ensured the fingers were always well supported.<br />

He played with an unusually loose bow, designed to enhance<br />

the natural resonances of his violin. His bow hold moved from<br />

the relatively firm hold he had after his lessons with Flesch to<br />

a more lithe, French style (complete with flexible index finger)<br />

following his contact with Thibaud. This change gave <strong>Szeryng</strong><br />

a more malleable sound.<br />

Despite the aristocratic precision of his technique, <strong>Szeryng</strong><br />

made everything look effortless. Camera close-ups reveal<br />

that during those vital seconds before a difficult entry in a<br />

concerto he invariably appeared nonchalant and unconcerned.<br />

The fingers of his left hand were extremely strong so that<br />

although he used only medium weight and pressure<br />

(he couldn’t abide banging the fingers down on the<br />

fingerboard), his playing possessed unusual clarity. He gave<br />

each and every note its own special weight, which created the<br />

strange impression on occasion that he was playing slower<br />

than he actually was, almost as though he was stretching<br />

time (the complete opposite, for example, of Heifetz).<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> generally employed a medium-paced, basic vibrato,<br />

yet by varying the finger weight, pulse and width, he obtained an<br />

unusually varied tonal palette. He preferred to enhance intensity<br />

not by increasing vibrato speed but by opening up the full width<br />

of the bow hair at high pressure, going daringly close to the<br />

bridge. In the upper reaches of the E string this had an effect akin<br />

to blinding light in its shimmering purity. To watch <strong>Szeryng</strong> was<br />

to experience a live masterclass in the art of playing the violin.<br />

sound<br />

The <strong>Szeryng</strong> sound was completely individual and had<br />

extraordinary penetration. Like most violinists of his<br />

generation, <strong>Szeryng</strong> concentrated on the middle and upper<br />

end of the dynamic range, yet with an openness and honesty<br />

free of the slightest hint of gloss or self-<br />

conscious allure. Despite its meticulous<br />

regulation, <strong>Szeryng</strong>’s sound possessed<br />

a tantalising combination of warmth<br />

and plangency that at its most poignant<br />

– as in the slow movement of the<br />

Saint-Saëns B minor Concerto – carried<br />

extraordinary emotional power.<br />

sTrengThs<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong>’s aristocratic interpretative<br />

demeanour and technical mastery<br />

imparted a profound sense of musical<br />

worth to everything he played. It didn’t<br />

matter whether it was Brahms or<br />

28 The sTrad JULY 2009 www.thestrad.com

Paganini, Beethoven or Khachaturian, Mozart or Kreisler,<br />

he made every work sound like a bona fide masterpiece.<br />

Weaknesses<br />

very occasionally, when accenting with a fast bow towards the<br />

end of his career, <strong>Szeryng</strong> would play through a note before it<br />

had focused properly, resulting in a glazed ‘whistle’. Some critics<br />

detect an occasional hint of emotional reserve in his playing.<br />

insTrumenTs and boWs<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong>’s principal instrument throughout his career was the<br />

1745 ‘Leduc’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, which he considered a violin<br />

without parallel. He generously gave away the dozen-or-so<br />

other instruments he owned at various times, including the<br />

‘Hercules’ Stradivari (a former Ysaÿe favourite), which he<br />

donated to the state of Israel in 1972, his ‘Messiah’ Stradivari<br />

copy by vuillaume, which he later presented to Prince<br />

Rainier III of Monaco, and the ‘Sancta Theresia’ Andrea<br />

Guarneri, which went to Mexico City.<br />

reperToire<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> was one of the most widely recorded of modern<br />

violinists. Out of a regular playing repertoire of some 250 pieces<br />

www.thestrad.com<br />

Despite the aristocratic<br />

precision of his technique,<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> made everything<br />

look effortless<br />

he took more than 150 into the recording<br />

studio, although currently the majority<br />

of these are awaiting reissue or in some<br />

cases transfer to CD. The essential<br />

purity of <strong>Szeryng</strong>’s playing style and<br />

interpretative vision can be savoured<br />

especially in music of the Baroque and<br />

Classical eras. His exemplary recording of<br />

Bach’s accompanied sonatas with Helmut<br />

Walcha is available as a Japanese import,<br />

and although his peerless first stereo<br />

recording of the Bach concertos (with<br />

Peter Rybar in the ‘Double’ Concerto)<br />

is difficult to find, the remake with<br />

Maurice Hasson is also extremely fine.<br />

Most celebrated of his Bach recordings is<br />

the stereo set of the Sonatas and Partitas.<br />

<strong>Szeryng</strong> was also a distinguished<br />

Mozartian, as witness supremely<br />

stylish accounts of the concertos with<br />

Alexander Gibson (inexplicably the<br />

Sinfonia concertante with Bruno<br />

Giuranna has never appeared on CD)<br />

and sonatas with Ingrid Haebler.<br />

He gave the modern premiere of<br />

Paganini’s Third Concerto, having tracked down the score<br />

with the help of the composer’s two octogenarian greatgranddaughters.<br />

He was a superb advocate of the central<br />

20th-century repertoire, and several composers dedicated<br />

works to him, including Carlos Chávez, Benjamin Lees,<br />

Jean Martinon and Manuel Ponce.<br />

EssEntial Facts<br />

1918 Born in Warsaw, Poland<br />

1930 Begins four years of study with Carl Flesch<br />

1933 Makes debut in Warsaw with the Brahms Concerto<br />

1933 Begins composition studies with nadia Boulanger<br />

1939 gives some 300 concerts for the Allies during World War II<br />

1946 Becomes a naturalised Mexican citizen<br />

1954 resumes playing career at suggestion of Artur rubinstein<br />

1970 Appointed Mexico’s special adviser to UnesCO<br />

1983 Fiftieth anniversary tour of the Us and europe<br />

1988 Dies in kassel, germany, aged 69<br />

nexT monTh ISaac Stern<br />

HenrYk szerYng<br />

JULY 2009 The sTrad 29