The Constitutional Law of Dreros - The Life And Death Of Democracy

The Constitutional Law of Dreros - The Life And Death Of Democracy

The Constitutional Law of Dreros - The Life And Death Of Democracy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Constitutional</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dreros</strong><br />

<strong>Dreros</strong>, a small ancient city in eastern Crete, is perhaps best known among contemporary<br />

classicists as the place where the earliest surviving Greek law on stone was carved. <strong>The</strong><br />

constitutional law is <strong>of</strong> great historical significance, if only because it provides<br />

archaeological evidence <strong>of</strong> the existence within the classical Greek world <strong>of</strong> non-<br />

Athenian experiments in government by assembly. Similar (if younger) evidence, for<br />

instance from the ancient Greek cities <strong>of</strong> Chios and Locris, has been available for some<br />

time, but typically the surviving inscriptions on bronze or stone from other Greek polities<br />

have been neglected, partly because they have gone missing, or because they seem at first<br />

sight to be so random and rare, which adds to their sense <strong>of</strong> unimportance, at least<br />

compared with the impressive findings from the Athenian polis.<br />

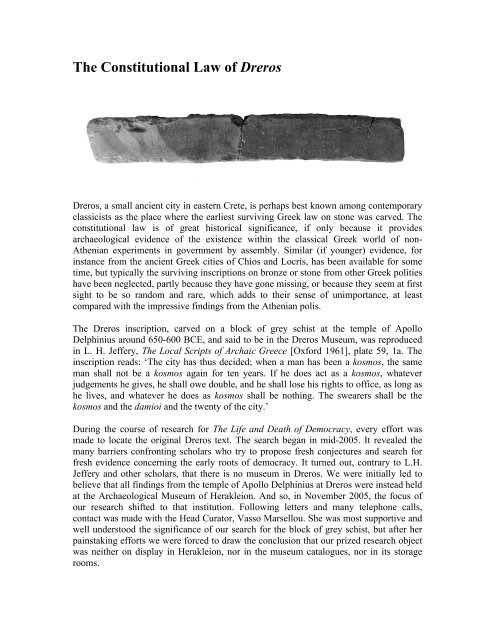

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Dreros</strong> inscription, carved on a block <strong>of</strong> grey schist at the temple <strong>of</strong> Apollo<br />

Delphinius around 650-600 BCE, and said to be in the <strong>Dreros</strong> Museum, was reproduced<br />

in L. H. Jeffery, <strong>The</strong> Local Scripts <strong>of</strong> Archaic Greece [Oxford 1961], plate 59, 1a. <strong>The</strong><br />

inscription reads: ‘<strong>The</strong> city has thus decided; when a man has been a kosmos, the same<br />

man shall not be a kosmos again for ten years. If he does act as a kosmos, whatever<br />

judgements he gives, he shall owe double, and he shall lose his rights to <strong>of</strong>fice, as long as<br />

he lives, and whatever he does as kosmos shall be nothing. <strong>The</strong> swearers shall be the<br />

kosmos and the damioi and the twenty <strong>of</strong> the city.’<br />

During the course <strong>of</strong> research for <strong>The</strong> <strong>Life</strong> and <strong>Death</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong>, every effort was<br />

made to locate the original <strong>Dreros</strong> text. <strong>The</strong> search began in mid-2005. It revealed the<br />

many barriers confronting scholars who try to propose fresh conjectures and search for<br />

fresh evidence concerning the early roots <strong>of</strong> democracy. It turned out, contrary to L.H.<br />

Jeffery and other scholars, that there is no museum in <strong>Dreros</strong>. We were initially led to<br />

believe that all findings from the temple <strong>of</strong> Apollo Delphinius at <strong>Dreros</strong> were instead held<br />

at the Archaeological Museum <strong>of</strong> Herakleion. <strong>And</strong> so, in November 2005, the focus <strong>of</strong><br />

our research shifted to that institution. Following letters and many telephone calls,<br />

contact was made with the Head Curator, Vasso Marsellou. She was most supportive and<br />

well understood the significance <strong>of</strong> our search for the block <strong>of</strong> grey schist, but after her<br />

painstaking efforts we were forced to draw the conclusion that our prized research object<br />

was neither on display in Herakleion, nor in the museum catalogues, nor in its storage<br />

rooms.

Trapped in a blind alley, we decided to contact a young Australian classics scholar, Dr<br />

David Pritchard, at the University <strong>of</strong> Queensland. In the spring <strong>of</strong> 2007 he helpfully<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered to send an email on our behalf to a vast database <strong>of</strong> classics scholars. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

them seemed familiar with the <strong>Dreros</strong> inscription and <strong>of</strong>fers <strong>of</strong> help poured in from<br />

different parts <strong>of</strong> the globe. We received various clues, ranging from advice that the<br />

inscription had been looted or lost during WWII to the suggestion that it was stored in a<br />

repository in Neapolis, a small town 2 kilometres from the archaeological site <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dreros</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> latter suggestion proved decisive. It came from Niki Ikonomaki, a PhD candidate at<br />

the University <strong>of</strong> Rethymnon in Crete, who at the time was studying archaic Cretan<br />

inscriptions. It transpired that the collection is operated by the Archaeological Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Aghios Nikolaos, and that it had been closed to the public for some time. Following<br />

Ikonomaki’s important leads (she kindly provided details <strong>of</strong> the exact location and<br />

catalogue code <strong>of</strong> the inscription), we finally (in July 2007) came in contact with the<br />

department responsible for its preservation, the 24 th Ephorate <strong>of</strong> Prehistoric and Classical<br />

Antiquities (EPKA).<br />

Navigating Greek bureaucracy was not easy, but with the kind help <strong>of</strong> the Ephorate’s<br />

director Stavroula Apostolakou and, in her absence, her colleague Vasso Zografaki, we<br />

succeeded in getting <strong>of</strong>ficial permission from the Greek Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture to have the<br />

inscription photographed. But since this was the first time that such a request had been<br />

made, and since we were based in London, we had to seek further assistance in arranging<br />

the photo shoot. This time the archaeologist Maria Kyriakaki’s suggestions proved<br />

valuable, since she put us in touch with Chronis Papanikolaou, the in–house specialist<br />

photographer at the Institute for Aegean Prehistory Study Center for East Crete. He set<br />

about arranging a visit to the closed collection unaware that he would locate the coveted<br />

object lying awkwardly on the floor, with the inscription facing upwards. Given that the<br />

block was physically impossible to move, and therefore difficult to photograph, Mr<br />

Papanikolaou had to be creative: using a high stepladder and helped by a security guard,<br />

he managed to do his job. <strong>The</strong> fruit <strong>of</strong> his labours finally reached our hands in July 2008,<br />

three years after our search for the inscription had first begun. A copy <strong>of</strong> the original<br />

photograph is reproduced above.<br />

Maria Fotou<br />

John Keane<br />

September 2009