the Albucciu nuraghe at Arzachena is a monument - Sardegna Cultura

the Albucciu nuraghe at Arzachena is a monument - Sardegna Cultura

the Albucciu nuraghe at Arzachena is a monument - Sardegna Cultura

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THE ALBUCCIU NURAGHE<br />

AND ARZACHENA’S MONUMENTS

Cover photo<br />

Nuraghe <strong>Albucciu</strong>: front view<br />

Transl<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

David C. Nilson<br />

ISBN 88-7138-267-6<br />

© Copyright 1992 by Carlo Delfino editore, Via Rolando 11/A, Sassari

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SARDINIA<br />

19<br />

Guidebooks and Itineraries<br />

The <strong>Albucciu</strong> Nuraghe<br />

and <strong>Arzachena</strong>’s Monuments<br />

Angela Antona Ruju - Maria Lu<strong>is</strong>a Ferrarese Ceruti<br />

Carlo Delfino editore

Gallura in preh<strong>is</strong>toric and proto-h<strong>is</strong>toric times<br />

Situ<strong>at</strong>ed in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>astern part of Sardinia, Gallura has welldefined<br />

n<strong>at</strong>ural boundaries: to <strong>the</strong> south <strong>the</strong> Limbara mountain range,<br />

to <strong>the</strong> north and east <strong>the</strong> sea, to <strong>the</strong> west <strong>the</strong> Coghinas River and <strong>the</strong><br />

last peaks of Limbara in <strong>the</strong> direction of <strong>the</strong> Anglona region. The<br />

largest part of <strong>the</strong>se boundaries <strong>is</strong> made up of jagged mountains th<strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong>ol<strong>at</strong>e it from <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land. These mountains become more<br />

accessible in <strong>the</strong> northwest, in <strong>the</strong> direction of <strong>the</strong> towns of Trinità<br />

d’Agultu and Vignola, and in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast, going towards <strong>the</strong> Olbia<br />

plain, where we find <strong>the</strong> only easy routes for entering and leaving <strong>the</strong><br />

Gallura region.<br />

The landscape <strong>is</strong> characterized by granite form<strong>at</strong>ions which, owing<br />

to erosion by wind and w<strong>at</strong>er, especially <strong>the</strong> former, give r<strong>is</strong>e to a quite<br />

varied landscape which towards <strong>the</strong> north gives way to fertile plains<br />

which often go down to <strong>the</strong> sea.<br />

The spontaneous veget<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>is</strong> composed of Mediterranean bush<br />

(lent<strong>is</strong>k, rock rose, arbutus and so on) especially where <strong>the</strong> wooded<br />

areas are less thick or on <strong>the</strong> plains which in some cases have only<br />

recently become farmland. On <strong>the</strong> steep mountain slopes <strong>the</strong> holmoak,<br />

juniper and cork oak have no rivals. The cork oak <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> tree th<strong>at</strong><br />

provides <strong>the</strong> raw m<strong>at</strong>erial for <strong>the</strong> flour<strong>is</strong>hing cork industry which,<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with animal husbandry, represents <strong>the</strong> region’s most important<br />

source of revenue. In recent decades <strong>the</strong> holiday industry, with <strong>the</strong><br />

development of <strong>the</strong> coasts, has become ano<strong>the</strong>r import source of<br />

income.<br />

Human presence, quite sparse up to <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> last century, <strong>is</strong><br />

now heavily concentr<strong>at</strong>ed in small and large towns, with <strong>the</strong> progressive<br />

abandonment of rural areas and <strong>the</strong> activities of farming and ani-<br />

5

mal husbandry. The stazzo, <strong>the</strong> typical farmstead of <strong>the</strong> region, loc<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

<strong>at</strong> some d<strong>is</strong>tance from <strong>the</strong> coast in a sunny position and economically<br />

self-sufficient, was for many years <strong>the</strong> pole around which all rural life<br />

revolved. It has now become, especially <strong>the</strong> ones nearest <strong>the</strong> coast, <strong>the</strong><br />

temporary home for families, often not Sardinian, who spend <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

summer holidays on <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land. Stazzi far<strong>the</strong>r from <strong>the</strong> coast are now<br />

occupied by transhumant shepherds who bring <strong>the</strong>ir flocks <strong>the</strong>re from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Barbagia region in <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land.<br />

The Palaeolithic (500,000 years ago)<br />

The presence of Palaeolithic man in Gallura has not yet been ascertained,<br />

even though <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> proof of such a presence on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r side<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Coghinas River, in <strong>the</strong> Anglona region. Here, numerous sites on<br />

fluvial terraces have yielded an enormous number of Clactonian artefacts<br />

and excav<strong>at</strong>ions have brought to light areas of fossil soil.<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>est studies, Palaeolithic man reached Sardinia<br />

some seven hundred thousand years ago following <strong>the</strong> Sardo-Corsican<br />

block which <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> time was separ<strong>at</strong>ed from <strong>the</strong> mainland only by a<br />

narrow sea channel in front of <strong>the</strong> Tuscan archipelago. Thus it <strong>is</strong> highly<br />

probable th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> present lack of evidence of h<strong>is</strong> presence in Gallura<br />

will soon be overcome.<br />

The Early Neolithic (VI-V millennium BC)<br />

The first traces of human presence in Gallura go back to <strong>the</strong> Early<br />

Neolithic Age. To d<strong>at</strong>e, two sites have yielded <strong>the</strong> character<strong>is</strong>tic<br />

Neolithic implements: pottery decor<strong>at</strong>ed with impressions made with<br />

<strong>the</strong> serr<strong>at</strong>ed edge of a shell (Cardium, Pectunculus or <strong>the</strong> apex of a<br />

Ciprea) found toge<strong>the</strong>r with typical small stone objects made of flint<br />

or obsidian shaped into geometric forms (trapeziums, half-moons, triangles<br />

and so on).<br />

Both <strong>the</strong> sites th<strong>at</strong> yielded traces of Neolithic man are loc<strong>at</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong><br />

coast, one <strong>at</strong> San Francesco d’Aglientu, in <strong>the</strong> locality known as Lu<br />

Litarroni, and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>at</strong> Cala Corsara, on <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land of Spargi: one<br />

was a fortuitous find, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r was certainly <strong>the</strong> site of a dwelling,<br />

6

albeit temporary. With research still in its early stages, it <strong>is</strong> difficult to<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>e with any exactitude <strong>the</strong> real importance of <strong>the</strong> finding <strong>at</strong> Lu<br />

Litarroni, while <strong>the</strong> Cala Corsara site, a tafone (a cavity in a granite<br />

boulder formed by erosion) used as a dwelling place has allowed careful<br />

observ<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> superimposition of archaeological layers since<br />

on <strong>the</strong> untouched bottom layer o<strong>the</strong>r cultural levels formed starting<br />

from <strong>the</strong> final years of <strong>the</strong> Early Neolithic.<br />

A wall of large granite boulders, of which two or three courses laid<br />

directly on <strong>the</strong> rock remain <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> extremities, in ancient times must<br />

have completely closed off <strong>the</strong> entrance to <strong>the</strong> cavity on <strong>the</strong> side facing<br />

<strong>the</strong> sea directly exposed to <strong>the</strong> northwestern m<strong>is</strong>tral, Sardinia’s<br />

strong prevailing wind and o<strong>the</strong>r bad wea<strong>the</strong>r conditions which without<br />

<strong>the</strong> wall would have made it impossible to inhabit <strong>the</strong> cave. The<br />

ancient entrance, of a very low, subrectangular shape, opened in <strong>the</strong><br />

back of <strong>the</strong> boulder, today in correspondence to a high-r<strong>is</strong>ing dune<br />

which formed quite recently, and in any case long after <strong>the</strong> time when<br />

<strong>the</strong> shelter was lived in.<br />

Changes in <strong>the</strong> coastline th<strong>at</strong> have taken place since Early Neolithic<br />

times have certainly been noteworthy and <strong>the</strong> tafone, <strong>the</strong>n far<strong>the</strong>r from<br />

<strong>the</strong> coastline than it <strong>is</strong> today (about eight metres), must have offered<br />

good shelter, albeit probably temporary, both for its size (4x3.7 metres)<br />

and because it was not far from fresh-w<strong>at</strong>er springs, which were ind<strong>is</strong>pensable<br />

to life on <strong>the</strong> small <strong>is</strong>land.<br />

The long period over which <strong>the</strong> cavity was put to use, starting from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Early Neolithic and continuing up to <strong>the</strong> age of <strong>the</strong> first nuraghi, <strong>is</strong><br />

proof of <strong>the</strong> good living conditions it offered.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> cave <strong>the</strong>re were numerous shards d<strong>at</strong>ing back<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Early Neolithic. In particular, cardial ware was found associ<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

with implements made of flint and obsidian: <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter <strong>is</strong> a volcanic<br />

glass coming from Monte Arci (near Or<strong>is</strong>tano) which was used, toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

with flint, in <strong>the</strong> making of tools and weapons.<br />

The presence of obsidian in <strong>the</strong> Cala Corsara tafone once again indic<strong>at</strong>es<br />

th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Maddalena archipelago was one of <strong>the</strong> way st<strong>at</strong>ions along<br />

<strong>the</strong> route of <strong>the</strong> ‘black gold’ of antiquity from Sardinia towards<br />

Neolithic settlements in Corsica, Tuscany, central and nor<strong>the</strong>rn Italy<br />

and sou<strong>the</strong>rn France.<br />

The brown flint found <strong>at</strong> Cala Corsara almost certainly came from<br />

<strong>the</strong> imposing deposits <strong>at</strong> Perfugas in <strong>the</strong> Anglona region just to <strong>the</strong><br />

7

west of Gallura. It was used both as raw m<strong>at</strong>erial for exchanges of<br />

goods within Sardinia and exported as a m<strong>at</strong>erial accompanying <strong>the</strong><br />

better-known Sardinian obsidian. Th<strong>is</strong> shows th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> routes to and<br />

from <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land must have been well known and Sardinia’s economic<br />

resources must have acted as an incentive for a more and more massive<br />

inflow of peoples and ideas. It <strong>is</strong> thus to be hoped th<strong>at</strong> large-scale labor<strong>at</strong>ory<br />

analyses can be performed on obsidian coming from excav<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

outside Sardinia, thus obtaining a better idea of <strong>the</strong> role played by<br />

Sardinia’s n<strong>at</strong>ural resources during <strong>the</strong> Early Neolithic, between <strong>the</strong><br />

6th and 5th millennia BC.<br />

The Middle Neolithic (VI-V millennium BC)<br />

The pottery and stone objects (quartz, granite, porphyry and obsidian<br />

– with flint strangely lacking) found on <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land of Santo Stefano<br />

during excav<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> overhanging rock shelter <strong>at</strong> Cala Villamarina,<br />

as well as some shards and obsidian weapons with transversal cutting<br />

edges found in <strong>the</strong> upper layers <strong>at</strong> Cala Corsara perhaps belong to <strong>the</strong><br />

Bonu Ighinu culture in <strong>the</strong> Middle Neolithic: <strong>the</strong>y are of <strong>the</strong> kinds<br />

found in many shelters, especially Sardinia’s caves, and in particular<br />

comparable to <strong>the</strong> findings <strong>at</strong> Su Carroppu, Sirri Carbonia in <strong>the</strong> Sulc<strong>is</strong><br />

area, <strong>the</strong> Grotta Verde <strong>at</strong> Alghero, <strong>the</strong> Sa Ucca de su Tintirriolu cave <strong>at</strong><br />

Mara and so on.<br />

The wealth of obsidian, especially in <strong>the</strong> Cala Villamarina shelter<br />

where it represents <strong>the</strong> stone most used in making utensils, indic<strong>at</strong>es a<br />

continu<strong>at</strong>ion of trade in th<strong>is</strong> stone towards Corsica, <strong>the</strong> Italian mainland<br />

(Tuscany, Emilia, Lombardy and so on) and through Liguria to<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn France (Provence).<br />

Temporary shelters for mariners or f<strong>is</strong>hermen, <strong>the</strong>se sites demonstr<strong>at</strong>e<br />

th<strong>at</strong> despite <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> up to now <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> almost no evidence of<br />

<strong>the</strong> presence of <strong>the</strong> Bonu Ighinu culture in <strong>the</strong> part of Gallura on terra<br />

firma, <strong>the</strong> occup<strong>at</strong>ion of th<strong>is</strong> region by peoples of <strong>the</strong> Middle Neolithic,<br />

between <strong>the</strong> 4th and 3rd millennia BC, must have been far more massive<br />

than wh<strong>at</strong> appears from <strong>the</strong> evidence <strong>at</strong> hand.<br />

Far from <strong>the</strong> coasts, where it was possible to practice an economy<br />

based on farming and animal husbandry, <strong>the</strong>re must still be proof of<br />

th<strong>is</strong> presence represented by st<strong>at</strong>ions in <strong>the</strong> open air, inhabited tafoni or<br />

8

tafoni used as burial sites. The finding on <strong>the</strong> outskirts of Olbia, in a<br />

place known as Orgosoleddu, of a st<strong>at</strong>uette of <strong>the</strong> Mo<strong>the</strong>r Goddess of<br />

<strong>the</strong> volumetric, n<strong>at</strong>ural<strong>is</strong>tic type belonging to <strong>the</strong> Bonu Ighinu culture<br />

<strong>is</strong> a clear indic<strong>at</strong>ion of th<strong>is</strong>.<br />

The L<strong>at</strong>e Neolithic (3500–2700 BC)<br />

Equally rare, although more cons<strong>is</strong>tent than <strong>the</strong> findings d<strong>at</strong>ing back<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Early and Middle Neolithic, are <strong>the</strong> sites of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture in<br />

Gallura.<br />

Currently, four localities where findings of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture have<br />

come to light are known: three are rock shelters <strong>at</strong> Aggius and Monte<br />

Icappidd<strong>at</strong>u <strong>at</strong> <strong>Arzachena</strong>. The former <strong>is</strong> a large tafone on <strong>the</strong> outskirts<br />

of <strong>the</strong> town of Aggius. The artefacts found <strong>the</strong>re were sc<strong>at</strong>tered and<br />

tampered with during modern renov<strong>at</strong>ion works. The l<strong>at</strong>ter presented a<br />

rich str<strong>at</strong>igraphy found in a deep f<strong>is</strong>sure, where many shards and stone<br />

implements had fallen by accident or had been washed in from <strong>the</strong><br />

large shelter above. The absence of human bones in both cases<br />

excludes <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> shelter as a burial site. The third site, <strong>at</strong> Cala<br />

Corsara on <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land of Spargi, has been described in detail in <strong>the</strong> sections<br />

dealing with <strong>the</strong> Early and Middle Neolithic.<br />

The fourth site cons<strong>is</strong>ts of a settlement in <strong>the</strong> open air, <strong>the</strong> only one<br />

known in Gallura, <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> locality known as Pilastru, or Pirastru, near<br />

<strong>Arzachena</strong>, where <strong>the</strong> road to Bassacutena was cut through a low r<strong>is</strong>e<br />

in <strong>the</strong> land, thus exposing some pockets containing archaeological<br />

deposits. The settlement made up of huts extends over <strong>the</strong> entire slope<br />

of <strong>the</strong> hill, down to <strong>the</strong> base where boulders r<strong>is</strong>e from north to east <strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> outer limit of <strong>the</strong> site and in which <strong>the</strong>re are many tafoni used in<br />

preh<strong>is</strong>toric times ei<strong>the</strong>r for shelter or as graves.<br />

Thus, in Gallura as well we find <strong>the</strong> presence of a building technique<br />

known in o<strong>the</strong>r parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land in <strong>the</strong> villages of th<strong>is</strong> age and th<strong>is</strong><br />

culture: <strong>the</strong> custom was to build dwellings th<strong>at</strong> were partially dug into<br />

<strong>the</strong> ground and covered with a wooden roof. They were known as fondi<br />

di capanne (dugout huts).<br />

Findings on <strong>the</strong> surface and quite recent excav<strong>at</strong>ions have brought to<br />

light shards, both smooth and decor<strong>at</strong>ed, with <strong>the</strong> traditional shapes<br />

and p<strong>at</strong>terns of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture (zigzag geometric p<strong>at</strong>terns, arcs, seg-<br />

9

ments of circles, spirals and so on) often with a two-colour effect<br />

obtained by filling in <strong>the</strong> engravings or impressions with white or red<br />

paste. There are also traces of <strong>the</strong> production of flint and obsidian<br />

implements. Summing up, we have a totally homogeneous cultural<br />

context similar to <strong>the</strong> one known all over <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land, thus once again<br />

confirming <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong> vital force expressed by <strong>the</strong>se peoples.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, similar to wh<strong>at</strong> has been found elsewhere in Sardinia<br />

– where <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture <strong>is</strong> well known owing to dozens of open settlements,<br />

caves used as dwelling places or graves, burial sites with<br />

small artificial caves (domus de janas) or stone c<strong>is</strong>ts closed within circles,<br />

religious sites and so on. The Ozieri people spread to wherever it<br />

was possible to develop an economy based on agriculture, animal husbandry<br />

and ga<strong>the</strong>ring, or where it was possible to add <strong>the</strong> exploit<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> n<strong>at</strong>ural resources in <strong>the</strong> soil, such as obsidian and flint, to <strong>the</strong>se<br />

activities .<br />

The research now under way in different parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land aims to<br />

find, within <strong>the</strong> framework of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture, <strong>the</strong> div<strong>is</strong>ions and<br />

changes it underwent over <strong>the</strong> centuries and for th<strong>is</strong> reason an <strong>at</strong>tempt<br />

<strong>is</strong> being made to place <strong>the</strong> Pilastru context with prec<strong>is</strong>ion. On preliminary<br />

examin<strong>at</strong>ion, some sectors of <strong>the</strong> Pilastru village would appear to<br />

show less variety in <strong>the</strong> decor<strong>at</strong>ion of pottery, less skill in applying<br />

decor<strong>at</strong>ions and a ra<strong>the</strong>r poor working of <strong>the</strong> clay used, which was of<br />

local origin, thin and full of inclusions.<br />

Character<strong>is</strong>tics of th<strong>is</strong> kind may suggest a long lifespan of <strong>the</strong><br />

Pilastru village, which began <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> time of gre<strong>at</strong>est vitality of <strong>the</strong> culture,<br />

<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> same time as <strong>the</strong> founding of <strong>the</strong> Aggius and Monte<br />

Incappidd<strong>at</strong>u settlements, since it <strong>is</strong> not sufficient to place all <strong>the</strong> blame<br />

for <strong>the</strong> poor quality of <strong>the</strong> paste and decor<strong>at</strong>ions on <strong>the</strong> poor quality of<br />

<strong>the</strong> clay.<br />

Chronologically contemporary with <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture, or local<br />

facies of it, <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> improperly named ‘<strong>Arzachena</strong> culture’ or ‘Gallura<br />

culture’, which <strong>is</strong> characterized by <strong>monument</strong>s cons<strong>is</strong>ting of circles<br />

sometimes enclosing a stone c<strong>is</strong>t destined for burial and accompanied<br />

by upright stones in <strong>the</strong> ground (menhirs), <strong>the</strong> so-called type A circles,<br />

<strong>the</strong> most well-known example of which <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> Li Muri circle <strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>Arzachena</strong>. Up to some time ago considered manifest<strong>at</strong>ions of an<br />

autonomous aspect of <strong>the</strong> Eneolithic, only recently have <strong>the</strong>y been recognized<br />

as belonging to <strong>the</strong> Ozieri cultural context.<br />

10

The m<strong>at</strong>erials found in <strong>the</strong>se grave circles belong to artefacts of <strong>the</strong><br />

Ozieri culture, with <strong>the</strong> closest resemblances being <strong>the</strong> spheroid pommels,<br />

<strong>the</strong> soapstone axes, <strong>the</strong> long, sharp unfin<strong>is</strong>hed flint blades, <strong>the</strong><br />

stone pots and in <strong>the</strong> custom of placing lumps of red ocre in graves, an<br />

auspice of resurrection.<br />

Finally, we must not forget <strong>the</strong> custom of building huts partially in<br />

<strong>the</strong> ground by digging large trenches, as can be seen in <strong>the</strong> villages of<br />

Cuccuru de <strong>is</strong> Arrius <strong>at</strong> Cabras, Su Coddu <strong>at</strong> Selargius, etc.<br />

Owing to all <strong>the</strong>se affinities and to <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> grave circles with<br />

menhirs now appear to have crossed <strong>the</strong> narrow boundaries of <strong>the</strong><br />

Gallura region (<strong>the</strong> example of <strong>the</strong> Pranu Mutteddu circle near Goni <strong>is</strong><br />

significant), recently <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>s<strong>is</strong> has been advanced th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> socalled<br />

‘<strong>Arzachena</strong> culture’ <strong>is</strong> to be considered a local facies of <strong>the</strong><br />

Ozieri culture, within which it developed. Since <strong>the</strong> affinities are limited<br />

only to <strong>the</strong> narrow sphere of <strong>the</strong> m<strong>at</strong>erial culture but also include<br />

ideological and religious aspects (red ocre in <strong>the</strong> graves, a close connection<br />

between grave circles and menhirs, etc.) it can be supposed<br />

th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture was present in Gallura in a far more radical way<br />

than <strong>the</strong> few settlements found so far would lead one to believe.<br />

The use of rock-cut tombs (domus de janas) appears in Gallura only<br />

sporadically and <strong>is</strong> limited to marginal areas where <strong>the</strong> cultural influences<br />

of adjacent areas (Anglona, Logudoro) penetr<strong>at</strong>ed more easily.<br />

The most interesting among <strong>the</strong>se, owing to <strong>the</strong> rich symbol<strong>is</strong>m associ<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

with burial, <strong>is</strong> th<strong>at</strong> of T<strong>is</strong>iennari Bortigiadas, which shows on <strong>the</strong><br />

back wall of <strong>the</strong> main cell a false entrance surmounted by an engraved<br />

double bull-horn p<strong>at</strong>tern and a row of V’s. Three rows of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter p<strong>at</strong>tern,<br />

of uncertain interpret<strong>at</strong>ion, also appear on <strong>the</strong> wall to <strong>the</strong> left. Red<br />

paint borders <strong>the</strong> decor<strong>at</strong>ive p<strong>at</strong>terns in accordance with a funerary<br />

symbol<strong>is</strong>m of regener<strong>at</strong>ion, which was common to all Sardinia <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

time of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture.<br />

It <strong>is</strong> probable th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack of domus de janas in <strong>the</strong> rest of Gallura<br />

<strong>is</strong> to be placed in rel<strong>at</strong>ionship with <strong>the</strong> large numbers of tafoni, some<br />

of which have <strong>the</strong> appearance of real domus de janas, beside circles as<br />

burial sites.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>monument</strong> present in Gallura, with some ten examples,<br />

which in <strong>the</strong> present st<strong>at</strong>e of our knowledge are difficult to d<strong>at</strong>e, are <strong>the</strong><br />

dolmens, to be found in <strong>the</strong> countryside around Luras, Luogosanto,<br />

<strong>Arzachena</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>r towns. These too are <strong>monument</strong>s th<strong>at</strong> can be<br />

11

found not only in Sardinia but in o<strong>the</strong>r Mediterranean countries and on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Atlantic coast of France and Gre<strong>at</strong> Britain as well. It <strong>is</strong> likely th<strong>at</strong>,<br />

similar to o<strong>the</strong>r phenomena of <strong>the</strong> kind in o<strong>the</strong>r parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land, th<strong>is</strong><br />

megalithic form made its appearance in <strong>the</strong> L<strong>at</strong>e Neolithic and continued<br />

on into l<strong>at</strong>er epochs.<br />

The Chalcolithic (Copper Age) (2700–1800 BC)<br />

The question of d<strong>at</strong>ing <strong>the</strong> beginnings of <strong>the</strong> Copper Age, which <strong>is</strong><br />

to say <strong>the</strong> first of <strong>the</strong> ages of metal, <strong>is</strong> controversial. Some place it <strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture, when it was gradually changing its physiognomy<br />

and emerging with a new series of fe<strong>at</strong>ures.<br />

The pottery, although in some cases it continued to show <strong>the</strong> same<br />

types and forms of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture, became heavier and heavier;<br />

some recipients ceased to be produced and o<strong>the</strong>rs came to <strong>the</strong> fore to<br />

s<strong>at</strong><strong>is</strong>fy new needs and tastes.<br />

Elabor<strong>at</strong>e decor<strong>at</strong>ions gave way to simpler ones, often obtained with<br />

<strong>the</strong> engraving of a straight line, and l<strong>at</strong>er d<strong>is</strong>appeared altoge<strong>the</strong>r. It <strong>is</strong><br />

to th<strong>is</strong> period th<strong>at</strong> perhaps it <strong>is</strong> possible to <strong>at</strong>tribute <strong>at</strong> least a part of <strong>the</strong><br />

Pilastru settlement <strong>at</strong> <strong>Arzachena</strong>, but <strong>at</strong> present <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> no evidence in<br />

Gallura giving us an understanding of <strong>the</strong> different aspects, <strong>the</strong> diffusion<br />

and <strong>the</strong> chronological limits of th<strong>is</strong> cultural period.<br />

There are only a few traces of m<strong>at</strong>erials th<strong>at</strong> can be <strong>at</strong>tributed with<br />

any certainty to <strong>the</strong> horizon of <strong>the</strong> Monte Claro culture. The wellknown<br />

grooved pottery, a few fragments of which come from <strong>the</strong> Li<br />

Lolghi tombs <strong>at</strong> <strong>Arzachena</strong> and <strong>the</strong> Monte de s’Ape tombs <strong>at</strong> Olbia, are<br />

of quite limited diffusion.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> most significant presence <strong>is</strong> certainly wh<strong>at</strong> was found in <strong>the</strong><br />

Cala Corsara tafone on <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land of Spargi which yielded grooved and<br />

smooth shards of <strong>the</strong> typical pottery th<strong>at</strong> characterizing <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

part of Sardinia. Indeed, as concerns <strong>the</strong> type of pottery, <strong>the</strong> decor<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

on it and, to some extent, its shape, <strong>the</strong> Monte Claro culture <strong>is</strong><br />

characterized by <strong>the</strong> vari<strong>at</strong>ions which allow an immedi<strong>at</strong>e identific<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> place from which <strong>the</strong> shards come: <strong>the</strong> ones found in<br />

Gallura are part of <strong>the</strong> Sassari group. Th<strong>is</strong> group <strong>is</strong> d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>hed by<br />

fairly compact clay, thin sides and shallow grooves around <strong>the</strong> widest<br />

circumference of <strong>the</strong> recipient.<br />

12

It <strong>is</strong> probably due only to a lack of inform<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>re are no<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r cons<strong>is</strong>tent findings th<strong>at</strong> can be <strong>at</strong>tributed to <strong>the</strong> period of <strong>the</strong><br />

Chalcolithic, or Copper Age. I refer to <strong>the</strong> Filigosa, Abealzu and Bell-<br />

Beaker cultures.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> fact <strong>is</strong> quite singular, especially as concerns <strong>the</strong> Bell-Beaker<br />

culture (<strong>the</strong> name comes from <strong>the</strong> shape of its most character<strong>is</strong>tic<br />

beaker, which resembles an upside-down bell) since th<strong>is</strong> culture had its<br />

origins in <strong>the</strong> Iberian Peninsula and expanded in <strong>the</strong> direction of eastern<br />

Europe and descended <strong>the</strong> Italian peninsula, over <strong>the</strong> plain of <strong>the</strong><br />

Po, Emilia, Tuscany, L<strong>at</strong>ium and down to Sicily. It also found its way<br />

to Sardinia and, to a lesser extent, Corsica.<br />

In Sardinia we can d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>h two different cultural streams, one<br />

from <strong>the</strong> French Midi, <strong>the</strong> oldest one, and a second which, following<br />

<strong>the</strong> Alpine passes of <strong>the</strong> Veneto region, reached <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land through<br />

Emilia and Tuscany. The former left richly decor<strong>at</strong>ed shards, decor<strong>at</strong>ive<br />

objects made of shells, aquamarine stones (soapstone) or bone,<br />

stone or copper weapons, <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter was characterized by recipients<br />

often with no decor<strong>at</strong>ion and fewer decor<strong>at</strong>ive objects.<br />

It <strong>is</strong> to be expected th<strong>at</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r excav<strong>at</strong>ions and explor<strong>at</strong>ions will<br />

integr<strong>at</strong>e our knowledge of <strong>the</strong> Copper Age in Sardinia, thus adding<br />

more to wh<strong>at</strong> we know of <strong>the</strong> cultural vic<strong>is</strong>situdes th<strong>at</strong> characterized<br />

preh<strong>is</strong>toric Gallura.<br />

The Early and Middle Bronze Age<br />

(1800-1600 / 1600-1300 BC)<br />

The new era, which in Sardinia saw <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong><br />

Bonnanaro culture, <strong>is</strong> more or less intensively present in Gallura, but it<br />

<strong>is</strong> on <strong>the</strong> lands around <strong>Arzachena</strong> th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest number of artefacts<br />

belonging to th<strong>is</strong> culture, which characterized <strong>the</strong> Early Bronze Age,<br />

have been found, albeit sporadically.<br />

The same phenomenon th<strong>at</strong> was observed in <strong>the</strong> Bell-Beaker culture<br />

<strong>is</strong> also found in <strong>the</strong> Bonnanaro culture: dwelling places, religious centres<br />

and fortific<strong>at</strong>ions are totally unknown.<br />

We <strong>the</strong>refore do not know anything about <strong>the</strong> forms, sizes or types<br />

of huts, just as we cannot reconstruct <strong>the</strong> uses, customs or beliefs in<br />

any way on <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>is</strong> of <strong>the</strong> results of excav<strong>at</strong>ions, except as concerns<br />

13

<strong>the</strong> world of <strong>the</strong> dead, since only graves offer some indic<strong>at</strong>ion of spiritual<br />

manifest<strong>at</strong>ions. We know, for example, th<strong>at</strong> among <strong>the</strong>se popul<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

a secondary deposition, which <strong>is</strong> to say th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> final burial cons<strong>is</strong>ted<br />

of <strong>the</strong> skeleton only after <strong>the</strong> flesh had fallen away. Th<strong>is</strong> custom,<br />

which <strong>is</strong> well documented, especially in <strong>the</strong> Sassari area, was in all<br />

probability in use throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land, especially when <strong>the</strong> archaeological<br />

situ<strong>at</strong>ion does not appear clearly and <strong>the</strong> bones, sc<strong>at</strong>tered about,<br />

give <strong>the</strong> impression of a grave th<strong>at</strong> has been plundered.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> overall picture. In detail, <strong>the</strong> oldest findings in Gallura<br />

belonging to <strong>the</strong> Early Bronze Age are offered by <strong>the</strong> architecture and<br />

grave goods found in <strong>the</strong> oldest part of <strong>the</strong> Li Lolghi <strong>monument</strong>, a<br />

‘gallery grave’ which, l<strong>at</strong>er on, was enlarged with <strong>the</strong> addition of a corridor<br />

to form a giants’ tomb which <strong>is</strong> slightly lower than <strong>the</strong> floor of<br />

<strong>the</strong> older grave site <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> top of a hill of <strong>the</strong> same name. Artefacts are<br />

to be ascribed to <strong>the</strong> Bonnanaro culture in <strong>the</strong> Corona Moltana aspect<br />

as well as to its earlier period, th<strong>at</strong> <strong>is</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Early Bronze Age, while <strong>the</strong><br />

addition to <strong>the</strong> structure d<strong>at</strong>es to <strong>the</strong> Middle Bronze Age and <strong>is</strong> to be<br />

<strong>at</strong>tributed to <strong>the</strong> Sa Turricola culture.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> Coddu Vecchiu burial site we find <strong>the</strong> same transform<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

a gallery grave into a giants’ tomb: th<strong>is</strong> transform<strong>at</strong>ion came about with<br />

<strong>the</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion of a large semicircular space delimited by stones placed<br />

upright in <strong>the</strong> ground in most cases or by a wall made of stone courses<br />

in front of <strong>the</strong> giants’ tomb. The entrance to <strong>the</strong> grave <strong>is</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> base<br />

of an arched stele domin<strong>at</strong>ing <strong>the</strong> forecourt, or exedra, a space set aside<br />

for offerings, incub<strong>at</strong>ion rituals and o<strong>the</strong>r religious rites.<br />

Compared to <strong>the</strong> graves just described, those of Li Mizzani <strong>at</strong> Palau<br />

and Monte de s’Ape <strong>at</strong> Olbia, although <strong>the</strong>y too are to be placed in <strong>the</strong><br />

context of <strong>the</strong> Middle Bronze Age, were built somewh<strong>at</strong> l<strong>at</strong>er. To th<strong>is</strong><br />

epoch, which for <strong>the</strong> time being cannot be d<strong>at</strong>ed prec<strong>is</strong>ely, belong <strong>the</strong><br />

giants’ tombs of Lu Brandali <strong>at</strong> Santa Teresa di Gallura and Moru <strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>Arzachena</strong>; <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter <strong>is</strong> loc<strong>at</strong>ed a few dozen metres from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Albucciu</strong><br />

<strong>nuraghe</strong>, to which it <strong>is</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ed.<br />

We have no proof th<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> time of Facies b of <strong>the</strong> Bonnanaro culture,<br />

known as <strong>the</strong> Sa Turricola culture, nuraghi were built in Gallura,<br />

similar to wh<strong>at</strong> can be said about o<strong>the</strong>r areas in central and sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Sardinia. However, it <strong>is</strong> likely th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malchittu complex (a ‘corridor’<br />

<strong>nuraghe</strong>, a large circular hut, a rectangular temple and a series of<br />

graves in tafoni) – of which only <strong>the</strong> temple has been completely exca-<br />

14

v<strong>at</strong>ed, with <strong>the</strong> conclusion th<strong>at</strong> it belongs to <strong>the</strong> full Sa Turricola aspect<br />

– was built over a short period of time. If, as appears likely, th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> true,<br />

as affinities in <strong>the</strong> construction suggest, we are dealing with one of <strong>the</strong><br />

oldest complexes in <strong>the</strong> Gallura region.<br />

The Nuragic Age (from approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 1500 BC)<br />

The beginning of <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong> megalithic era <strong>is</strong> commonly placed <strong>at</strong><br />

about <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> second millennium BC, during <strong>the</strong> Middle<br />

Bronze Age. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> time th<strong>at</strong> saw <strong>the</strong> prolifer<strong>at</strong>ion throughout<br />

Sardinia of <strong>the</strong> constructions known by <strong>the</strong>ir ancient name of nuraghi.<br />

Gallura <strong>is</strong> no exception but, as said previously, <strong>the</strong>re are still some<br />

doubts about when <strong>the</strong> phenomenon started and, above all, if and when<br />

cultural rel<strong>at</strong>ions with nearby Corsica may have influenced <strong>the</strong> form,<br />

<strong>the</strong> plan, in a word <strong>the</strong> architecture, of <strong>the</strong>se megalithic <strong>monument</strong>s.<br />

And not only th<strong>at</strong>: it must be kept in mind th<strong>at</strong> pottery quite similar to<br />

th<strong>at</strong> of <strong>the</strong> contexts of Sa Turricola are present in torre <strong>monument</strong>s in<br />

Corsica and, although we have no objective evidence of <strong>the</strong> actual<br />

presence of <strong>the</strong> Sa Turricola aspect in <strong>the</strong> nuraghi in Gallura, <strong>the</strong> finding<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se shards typical of <strong>the</strong> Malchittu temple lead one to expect<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir presence in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r constructions of <strong>the</strong> complex as well.<br />

Lacking a proper census of all nuragic buildings, today it <strong>is</strong> impossible<br />

to establ<strong>is</strong>h <strong>the</strong> number and type of <strong>monument</strong>s present in<br />

Gallura. The inform<strong>at</strong>ion available, although scanty, points to a wide<br />

diffusion of megalithic buildings spreading to all parts of <strong>the</strong> region,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> sole exception of <strong>the</strong> highest mountain areas (for example<br />

Limbara) <strong>at</strong> altitudes from sea level (<strong>the</strong> lands of San Francesco<br />

d’Aglientu, Santa Teresa di Gallura, <strong>Arzachena</strong> and especially <strong>the</strong><br />

plain of Olbia) up to about seven hundred metres. But <strong>the</strong> nuragic peoples<br />

did not choose <strong>the</strong> highest areas for <strong>the</strong>ir settlements; <strong>the</strong>y preferred<br />

to settle in areas no more than one hundred and fifty metres a.s.l.<br />

or in <strong>the</strong> level between four hundred and five hundred metres, where<br />

<strong>the</strong> clim<strong>at</strong>e <strong>is</strong> milder and living conditions are better. At such altitudes<br />

it was in fact easier to practice an economy based on a mixture of agriculture<br />

and animal husbandry, with <strong>the</strong> contemporary exploit<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> rich pastureland on <strong>the</strong> hills and <strong>the</strong> fertile soils of <strong>the</strong> plain.<br />

Even when nuraghi were erected on fl<strong>at</strong> lands, <strong>the</strong> choice of sites<br />

15

went preferably to <strong>the</strong> low rocky hills r<strong>is</strong>ing above <strong>the</strong> surrounding<br />

countryside, because such areas were without <strong>the</strong> marshy lowlands,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y provided <strong>the</strong> n<strong>at</strong>ural rock for <strong>the</strong>ir buildings and because such<br />

r<strong>is</strong>es offered a good view of <strong>the</strong> land on all sides. Around <strong>the</strong> nuraghi<br />

we often find a more or less large, more or less well preserved village<br />

of huts, such as Lu Brandali <strong>at</strong> Santa Teresa, <strong>Albucciu</strong> and La Pr<strong>is</strong>ciona<br />

<strong>at</strong> <strong>Arzachena</strong>, and so on.<br />

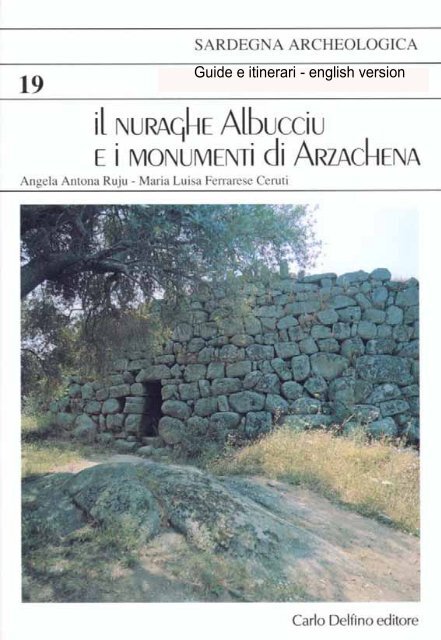

Fundamentally, we find two kinds of nuraghi in Gallura: <strong>the</strong> ‘tholos’<br />

<strong>nuraghe</strong> and <strong>the</strong> ‘corridor’ <strong>nuraghe</strong>. In its simplest form, <strong>the</strong> former <strong>is</strong><br />

a circular building, r<strong>is</strong>ing as a trunc<strong>at</strong>ed cone and topped by a terrace.<br />

The rooms, one above <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, are covered with a corbelled roof (tholos)<br />

and are connected by means of a spiral stairway inside <strong>the</strong> walls<br />

which goes up to <strong>the</strong> terrace.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> need ar<strong>is</strong>es to enlarge th<strong>is</strong> kind of <strong>nuraghe</strong>, two, three,<br />

four or more towers are erected around <strong>the</strong> original tower and are connected<br />

by rectangular curtain walls or concave-convex bastions. Th<strong>is</strong><br />

led to <strong>the</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> imposing fortresses from <strong>the</strong> b<strong>at</strong>tlements of<br />

which it was possible to defend against enemy <strong>at</strong>tacks or keep w<strong>at</strong>ch<br />

over livestock. These are buildings in which spaces were d<strong>is</strong>tributed<br />

vertically and covered with corbelled roofs and which could reach<br />

gre<strong>at</strong> heights.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> contrary, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r type of <strong>nuraghe</strong>, known as ‘corridor’<br />

nuraghi owing to <strong>the</strong> presence of more or less numerous corridors of<br />

differing lengths and more or less winding. These corridors, covered<br />

by slabs of stone, sometimes reach dimensions such as to make <strong>the</strong>m<br />

liveable. The chambers are generally small and are never very high,<br />

contrary to wh<strong>at</strong> we find in <strong>the</strong> tholos nuraghi, where <strong>the</strong> beehive<br />

chambers were sometimes divided by intermedi<strong>at</strong>e wooden floors, thus<br />

doubling <strong>the</strong> living space. In rare cases, such as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Albucciu</strong> <strong>nuraghe</strong><br />

<strong>at</strong> <strong>Arzachena</strong>, we find large tholos chambers toge<strong>the</strong>r with narrow corridors<br />

in a single <strong>monument</strong>.<br />

In corridor nuraghi <strong>the</strong> terrace had a fundamental function in <strong>the</strong> life<br />

of <strong>the</strong> community, and th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> especially evident since <strong>the</strong> horizontal<br />

layout of <strong>the</strong> rooms left room for a large terrace where it was possible<br />

to tend to daily chores.<br />

Both kinds of <strong>nuraghe</strong> are present in Gallura, with a prevalence of<br />

<strong>the</strong> tholos type, especially on <strong>the</strong> plains, while <strong>the</strong> corridor type <strong>is</strong><br />

found in <strong>the</strong> granite form<strong>at</strong>ions of <strong>the</strong> higher lands, against which <strong>the</strong>y<br />

16

were built to exploit irregularities for use as rooms or corridors. In our<br />

present st<strong>at</strong>e of knowledge we cannot define with any certainty <strong>the</strong><br />

genes<strong>is</strong> of <strong>the</strong> corridor <strong>nuraghe</strong>, its area of origin or <strong>the</strong> cultural influences<br />

behind it. A fundamental role may have been played by <strong>the</strong><br />

rough granite form<strong>at</strong>ions and <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong> many n<strong>at</strong>ural recesses in <strong>the</strong><br />

rock (tafoni) present throughout <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

Thus we find in Gallura <strong>the</strong> same phenomenon also to be found frequently<br />

in Corsica: a strong characteriz<strong>at</strong>ion and differenti<strong>at</strong>ion in<br />

nuragic constructions which, although not unknown in o<strong>the</strong>r mountainous<br />

areas of Sardinia, here acquire a unique impressiveness, perhaps<br />

owing to <strong>the</strong> morphology of <strong>the</strong> land. In Corsica <strong>the</strong> torre <strong>monument</strong>s,<br />

quite similar to nuraghi, are present only in a limited area in <strong>the</strong><br />

south of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land, <strong>the</strong> part closest to Sardinia and which shows <strong>the</strong><br />

same geological and morphological character<strong>is</strong>tics.<br />

But, as has been said, it was not only <strong>the</strong> <strong>nuraghe</strong> th<strong>at</strong> gave shelter<br />

to <strong>the</strong> popul<strong>at</strong>ions. Also present are simple walls, quite thick and<br />

robust, which stretched from one point of a higher granite form<strong>at</strong>ion to<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r, thus blocking access to <strong>the</strong> mountain <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> points without n<strong>at</strong>ural<br />

barriers. Today we count approxim<strong>at</strong>ely twenty-two such fortific<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

and as research proceeds <strong>the</strong>ir number will tend to increase,<br />

thus revealing a fairly uniform territorial d<strong>is</strong>tribution. The best known<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se walls <strong>is</strong> in <strong>the</strong> area of <strong>Arzachena</strong>. It <strong>is</strong> wavy and about forty<br />

metres long, defending a series of structures: shelters under overhanging<br />

rock, walled rooms and terraces th<strong>at</strong> have come down to us from<br />

nuragic peoples.<br />

Even today <strong>the</strong> presence of religious edifices <strong>is</strong> quite scarce. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong><br />

especially true of well temples, constructions where rites of <strong>the</strong> w<strong>at</strong>er<br />

cult were performed. Particularly frequent on Olbia’s municipal lands,<br />

and especially on <strong>the</strong> edges of its plain where <strong>the</strong> Padrongianus and La<br />

Fossa streams with <strong>the</strong>ir affluents take <strong>the</strong> w<strong>at</strong>ers from Limbara and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Berchiddeddu mountains down to <strong>the</strong> sea. These <strong>monument</strong>s are<br />

currently unknown elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> region. It cannot be st<strong>at</strong>ed with<br />

certainty th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> scarcity of well temples in Gallura <strong>is</strong> a demonstr<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> limited diffusion of <strong>the</strong> cult connected with spring w<strong>at</strong>ers, while<br />

it <strong>is</strong> quite probable th<strong>at</strong> careful explor<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> territory would lead<br />

to <strong>the</strong> finding of even a large number of <strong>the</strong>se sites.<br />

Of special interest <strong>is</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r religious <strong>monument</strong> loc<strong>at</strong>ed in <strong>the</strong><br />

countryside of <strong>Arzachena</strong>: <strong>the</strong> rectangular Malchittu temple in which,<br />

17

in all probability, community rites took place, since we find benches<br />

placed along <strong>the</strong> right side of <strong>the</strong> chamber and a circular hearth <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

centre.<br />

Well temples and ‘megaron’ temples, <strong>the</strong> two kinds just described,<br />

are constructions found all over Sardinia, but it <strong>is</strong> not known to which<br />

divinity <strong>the</strong>se rectangular temples were dedic<strong>at</strong>ed, just as we have no<br />

knowledge of <strong>the</strong> one to whom <strong>the</strong> well temples were dedic<strong>at</strong>ed, except<br />

for <strong>the</strong> generic st<strong>at</strong>ement th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>y must have been w<strong>at</strong>er divinities.<br />

We have already spoken of <strong>the</strong> graves known as ‘giants’ tombs’ and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir h<strong>is</strong>toric and cultural position, <strong>at</strong> least in <strong>the</strong>ir oldest phases.<br />

The Li Lolghi tomb presents two d<strong>is</strong>tinct building stages. The oldest<br />

cons<strong>is</strong>ts of a gallery grave with <strong>the</strong> unusual fe<strong>at</strong>ure of having <strong>the</strong><br />

entrance corridor wider than <strong>the</strong> burial chamber. The second stage <strong>is</strong><br />

represented by <strong>the</strong> addition of a burial chamber below ground level<br />

which penetr<strong>at</strong>es into <strong>the</strong> older corridor, thus incorpor<strong>at</strong>ing it.<br />

Archaeological d<strong>at</strong>a show th<strong>at</strong> it was used throughout <strong>the</strong> nuragic period,<br />

with no vari<strong>at</strong>ion in <strong>the</strong> burial rite, which <strong>is</strong> th<strong>at</strong> of collective burial,<br />

sometimes with primary burial and sometimes with <strong>the</strong> burial of<br />

<strong>the</strong> bones only (secondary burial) following <strong>the</strong> falling away of <strong>the</strong><br />

flesh.<br />

Burials in tafoni were instead of single individuals. These graves<br />

were in n<strong>at</strong>ural rock cavities and were closed off with dry walls.<br />

As concerns d<strong>at</strong>ing, <strong>the</strong> two kinds of burial appear to have been in<br />

use <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> same time, but <strong>the</strong> evidence th<strong>at</strong> has emerged thus far from<br />

excav<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>is</strong> not sufficient to determine whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> choice of one or<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r was based on wealth or birth.<br />

The custom of burial in tafoni, as <strong>is</strong> also th<strong>at</strong> of burial in giants’<br />

tombs, <strong>is</strong> d<strong>is</strong>semin<strong>at</strong>ed throughout Gallura, but it <strong>is</strong> of special interest<br />

to note th<strong>at</strong> quite often, for example <strong>at</strong> Lu Brandali near Santa Teresa,<br />

<strong>the</strong> two kinds of burial are present <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> same time and yield <strong>the</strong> same<br />

kind of shards, thus making <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>ing of each type quite difficult.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> overall d<strong>at</strong>a we have mentioned thus far emerges an overall<br />

picture th<strong>at</strong> can be seen throughout <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land. It <strong>is</strong> certain<br />

th<strong>at</strong> in many cases <strong>the</strong> rugged n<strong>at</strong>ure of <strong>the</strong> terrain influenced <strong>the</strong><br />

way of life and <strong>the</strong> choice of sites for settlements, just as <strong>the</strong> jagged<br />

rock form<strong>at</strong>ions often imposed quite special architectural solutions.<br />

Even <strong>the</strong> products of <strong>the</strong> m<strong>at</strong>erial culture are perfectly in line, both<br />

by type and d<strong>at</strong>ing, with those found in constructions of <strong>the</strong> same peri-<br />

18

od in <strong>the</strong> rest of Sardinia, thus demonstr<strong>at</strong>ing unequivocally th<strong>at</strong><br />

Gallura’s h<strong>is</strong>torical and cultural vic<strong>is</strong>situdes conform to those of <strong>the</strong><br />

rest of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>land and th<strong>at</strong> it was open to exchanges and contacts, but<br />

with <strong>the</strong> personal re-elabor<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> experiences and ideas of <strong>the</strong><br />

cultural heritage common to all Sardinia.<br />

The presence <strong>at</strong> <strong>Albucciu</strong> of ingots of <strong>the</strong> ‘Aegean-Cypriot’ type and<br />

pigs of copper proves <strong>the</strong> ex<strong>is</strong>tence of lively exchanges in <strong>the</strong> wake of<br />

which stimuli and impulses probably also arrived to <strong>at</strong>tenu<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> partial<br />

<strong>is</strong>ol<strong>at</strong>ion towards <strong>the</strong> south of <strong>the</strong>se peoples because of geographic<br />

and morphological conditions. Since <strong>the</strong> coasts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>lands of <strong>the</strong><br />

Maddalena archipelago present many good harbours, <strong>the</strong> presence of<br />

preh<strong>is</strong>toric settlers <strong>is</strong> sporadic and almost exclusively on <strong>the</strong> larger<br />

<strong>is</strong>lands, where it was possible to live comfortably, albeit occasionally,<br />

owing to particularly favourable living conditions for small groups for<br />

a limited time, <strong>the</strong> absence of nuragic buildings <strong>is</strong> surpr<strong>is</strong>ing.<br />

It appears to be improbable th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> reason for th<strong>is</strong> refusal to cre<strong>at</strong>e<br />

stable settlements on <strong>the</strong> <strong>is</strong>lands of <strong>the</strong> archipelago <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack of<br />

springs of drinkable w<strong>at</strong>er since elsewhere, as for example on <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong>land of Mal di Ventre in front of Or<strong>is</strong>tano, certainly no bigger than<br />

<strong>the</strong> Maddalena <strong>is</strong>lands and much far<strong>the</strong>r from <strong>the</strong> coast than <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> a large nuragic complex. The causes are probably to be<br />

searched for in ano<strong>the</strong>r direction, perhaps in customs more closely<br />

connected with life on <strong>the</strong> terra firma.<br />

MARIA LUISA FERRARESE CERUTI<br />

19

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– C H RONOLOGICAL TABLE –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––<br />

20<br />

500.000 BC<br />

100.000 BC<br />

35.000 BC<br />

10.000 BC<br />

6.000 BC<br />

4.000 BC<br />

3.500 BC<br />

2.700 BC.<br />

2.500 BC<br />

2.000 BC<br />

1.800 BC<br />

1.600 BC<br />

1.300 BC<br />

900 BC<br />

750 BC<br />

510 BC<br />

238 BC<br />

0<br />

476 AD<br />

PALAEOLITHIC<br />

NEOLITHIC<br />

ENEOLITHIC<br />

BRONZE AGE<br />

LOWER<br />

MIDDLE<br />

UPPER<br />

MESOLITHIC<br />

IRON AGE<br />

EARLY<br />

MIDDLE<br />

LATE<br />

INITIAL<br />

DEVELOPED<br />

FINAL<br />

EARLY<br />

MEDIUM<br />

LATE<br />

ORIENTALIZING ARCHAIC<br />

PUNIC CIVILIZATION<br />

ROMAN AGE<br />

RECENT<br />

FINAL<br />

CLACTONIAN<br />

RIO ALTANA<br />

(Perfugas)<br />

CORBEDDU<br />

CAVE<br />

(Oliena)<br />

SU CARROPPU<br />

FILIESTRU<br />

GREEN CAVE<br />

BONU IGHINU<br />

OZIERI<br />

SUB OZIERI<br />

FILIGOSA<br />

ABEALZU<br />

MONTE CLARO<br />

BELL BEAKER<br />

BONNANARO<br />

NURAGIC<br />

CIVILIZATION<br />

PHOENICIAN<br />

REPUBLICAN<br />

IMPERIAL

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL MONUMENTS<br />

ON ARZACHENA’S MUNICIPAL LANDS<br />

The archaeological heritage of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arzachena</strong> area may be considered<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> most interesting ones in Sardinia from <strong>the</strong> viewpoints<br />

of <strong>the</strong> density of <strong>monument</strong>s in rel<strong>at</strong>ion to its extension, <strong>the</strong>ir variety<br />

(burial and ritual circles, rock shelters, tafoni used for burials, dolmens,<br />

nuraghi, megalithic defensive walls and fortified villages, nuragic<br />

temples) and of <strong>the</strong> abundance of scientific d<strong>at</strong>a th<strong>at</strong> has emerged<br />

from excav<strong>at</strong>ions performed starting from 1939. Such d<strong>at</strong>a have ra<strong>is</strong>ed<br />

new questions concerning our knowledge of Sardinia’s preh<strong>is</strong>tory in<br />

general and of th<strong>at</strong> of <strong>the</strong> Gallura region in particular.<br />

The d<strong>is</strong>covery of <strong>the</strong> main <strong>monument</strong>s found up to now <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> merit<br />

of a well-deserving citizen of <strong>Arzachena</strong>, Michele Ruzittu (1871-<br />

1960), an elementary-school teacher best known among h<strong>is</strong> fellow<br />

townsfolk with <strong>the</strong> affection<strong>at</strong>e nickname of Babboi Micàli. Th<strong>is</strong> person,<br />

who was a gold mine of initi<strong>at</strong>ives of a civil and political n<strong>at</strong>ure<br />

in favour of self-rule for <strong>the</strong> town of h<strong>is</strong> birth, was also <strong>the</strong> author of<br />

an impassioned and sometimes imagin<strong>at</strong>ive Cron<strong>is</strong>toria di <strong>Arzachena</strong>,<br />

dall’età della pietra ai nostri giorni (Chronicle of <strong>Arzachena</strong>, from <strong>the</strong><br />

Stone Age to <strong>the</strong> present), publ<strong>is</strong>hed in Or<strong>is</strong>tano in 1948, a work written,<br />

in <strong>the</strong> words of <strong>the</strong> author, “with warm p<strong>at</strong>riotic sentiment”.<br />

It was <strong>the</strong> same sentiment th<strong>at</strong> inspired him, when he was in h<strong>is</strong> sixties<br />

and seventies, to devote himself “to <strong>the</strong> search for and meticulous<br />

study of <strong>monument</strong>s of remote antiquity on <strong>the</strong> municipal lands of <strong>the</strong><br />

reborn town” with <strong>the</strong> intention of “highlighting <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong><br />

region in all periods of h<strong>is</strong>tory and preh<strong>is</strong>tory”.<br />

The continu<strong>at</strong>ion of research and scientific excav<strong>at</strong>ions performed<br />

starting from 1940 by <strong>the</strong> Superintendency of Antiquities for Sardinia,<br />

which were intensified following <strong>the</strong> setting up of <strong>the</strong> Superintendency<br />

of Archaeology for <strong>the</strong> Provinces of Sassari and Nuoro, have brought<br />

to light a series of important findings proving <strong>the</strong> ex<strong>is</strong>tence of a succession<br />

of cultural aspects which, starting from <strong>the</strong> L<strong>at</strong>e Neolithic,<br />

continued up through most of <strong>the</strong> Roman period.<br />

The L<strong>at</strong>e Neolithic has been documented both in its civil aspect<br />

(Monte Incappidd<strong>at</strong>u, Pilastru) and burial customs (Li Muri and La<br />

Macciunitta), while <strong>the</strong> early metal ages are borne witness to by <strong>the</strong><br />

dolmens and shelters under overhanging rocks.<br />

21

The many nuraghi, <strong>the</strong> villages, <strong>the</strong> giants’ tombs and <strong>the</strong> fortified<br />

areas of Monte Mazzolu, Monte Tiana and Punta Candela, situ<strong>at</strong>ed on<br />

pl<strong>at</strong>eaus with a wealth of tafoni used as dwellings or graves, are proof<br />

of <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> nuragic civiliz<strong>at</strong>ion with aspects peculiar to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Gallura region.<br />

Up to <strong>the</strong> present, traces of <strong>the</strong> Punic period are scanty and limited<br />

to <strong>the</strong> very recent d<strong>is</strong>covery of a small stele with <strong>the</strong> inscription of <strong>the</strong><br />

letter daleth and a coin with <strong>the</strong> head of Thanit and an equine protome<br />

(300 – 264 BC) in <strong>the</strong> Moru giants’ tomb.<br />

The findings d<strong>at</strong>ing from <strong>the</strong> Roman period th<strong>at</strong> have come to light<br />

thus far are not yet sufficient to identify <strong>the</strong> site of Turobole Minor (or<br />

Turibulo Minore), a st<strong>at</strong>ion mentioned in <strong>the</strong> Itinerarium<br />

Antoninianum (3rd century AD) <strong>at</strong> XIV Roman miles from Olbia and<br />

which some scholars, based on a reconstruction of a coastal road,<br />

believe <strong>is</strong> to be found in <strong>the</strong> Gulf of <strong>Arzachena</strong>. There are traces of<br />

Roman roads elsewhere in Gallura, in Calangianus, Tempio, Santa<br />

Teresa and of course Olbia.<br />

The presence of <strong>the</strong> <strong>at</strong>tribute ‘minor’ has led to <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>s<strong>is</strong> of <strong>the</strong><br />

ex<strong>is</strong>tence of a Turobole Major (or Turibulo Majore), but <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> no<br />

Fig. 1 Li Muri burial circles in a photo taken during excav<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

22

proof of th<strong>is</strong>, while sites such as Viniola, Tibula, and Longon<strong>is</strong> are h<strong>is</strong>torically<br />

documented.<br />

1<br />

The Li Muri Necropol<strong>is</strong><br />

ANGELA ANTONA RUJU<br />

Of <strong>Arzachena</strong>’s archaeological <strong>monument</strong>s, <strong>the</strong> L<strong>at</strong>e Neolithic Li<br />

Muri necropol<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> best known complex.<br />

It <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> uniqueness of <strong>the</strong> graves found in it th<strong>at</strong> suggested th<strong>at</strong> it<br />

might well represent a peculiar culture to which was assigned <strong>the</strong> name<br />

of ‘megalithic circle culture’ or ‘<strong>Arzachena</strong> culture’ or ‘Gallura culture’.<br />

Effectively, in th<strong>is</strong> region <strong>the</strong> grave circles with stone c<strong>is</strong>ts are especially<br />

concentr<strong>at</strong>ed, but recent research adv<strong>is</strong>es caution in considering<br />

<strong>the</strong> so-called ‘circle culture’ a phenomenon independent of <strong>the</strong> contemporary<br />

Ozieri culture, which <strong>is</strong> found all over Sardinia.<br />

The Li Muri necropol<strong>is</strong>, d<strong>is</strong>covered in 1939 by Michele Ruzittu, was<br />

excav<strong>at</strong>ed by Francesco Sold<strong>at</strong>i for account of <strong>the</strong> Superintendency of<br />

Antiquities of Sardinia and was studied and publ<strong>is</strong>hed by Salv<strong>at</strong>ore<br />

Maria Pugl<strong>is</strong>i in 1941.<br />

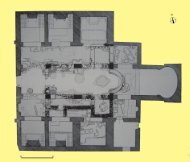

It cons<strong>is</strong>ts of a series of dolmen c<strong>is</strong>ts – small cells for burial made<br />

up of slabs placed edgew<strong>is</strong>e and with one as a cover – each one surrounded<br />

by a series of small slabs arranged in concentric circles. The<br />

purpose of <strong>the</strong>se circles was to contain a mound of earth and gravel<br />

covering <strong>the</strong> grave and keep it from being washed away.<br />

Should th<strong>is</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>s<strong>is</strong> prove true, <strong>the</strong> necropol<strong>is</strong> must have<br />

appeared as a series of small round mounds tangent to each o<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

having a diameter varying from 5.3 to 8.5 metres.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> external circle of each grave <strong>the</strong> remains of a menhir, a stone<br />

cippus with religious significance which, lacking reliable d<strong>at</strong>a, can be<br />

interpreted in different ways: it may have had <strong>the</strong> value of a betyl (from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hebrew beth-el), meaning <strong>the</strong> ‘home of <strong>the</strong> god’ which protected<br />

<strong>the</strong> dead; or it may have represented a way of identifying <strong>the</strong> person<br />

buried bene<strong>at</strong>h by means of symbols painted on <strong>the</strong> surface.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> several hypo<strong>the</strong>ses advanced, Castaldi put forth one<br />

based on experience in <strong>the</strong> field of ethnology: according to a belief<br />

23

Fig. 2 Li Muri burial circles: plan.<br />

24

held by several peoples, <strong>the</strong> spirit of <strong>the</strong> person who had just died<br />

walks in circles around h<strong>is</strong> corpse trying to understand h<strong>is</strong> or her new<br />

essence. In th<strong>is</strong> case <strong>the</strong> cippus may have represented <strong>the</strong> refuge of th<strong>at</strong><br />

spirit.<br />

Besides <strong>the</strong> menhirs, <strong>the</strong> three small stone chests (40x50 cm) placed<br />

near <strong>the</strong> points where <strong>the</strong> grave circles touched may have been connected<br />

with <strong>the</strong> cult of <strong>the</strong> dead and were for <strong>the</strong> purpose of receiving<br />

periodic offers for <strong>the</strong> deceased. We cannot exclude <strong>the</strong> possibility th<strong>at</strong><br />

such offers cons<strong>is</strong>ted of food, perhaps placed in containers made of<br />

per<strong>is</strong>hable m<strong>at</strong>erial, such as wood. Th<strong>is</strong> would explain <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong><br />

nothing has ever been found inside <strong>the</strong>se chests.<br />

Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely we do not even have enough of <strong>the</strong> remains of <strong>the</strong><br />

skeletons of those buried in <strong>the</strong> c<strong>is</strong>ts to allow an anthropological examin<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

due to <strong>the</strong> acidity of <strong>the</strong> granite soil. Only a few sh<strong>at</strong>tered fragments<br />

of long bones have been found. Th<strong>is</strong> situ<strong>at</strong>ion has made it<br />

impossible to establ<strong>is</strong>h <strong>the</strong> human type to which <strong>the</strong> Li Muri settlement<br />

belonged, nor <strong>the</strong> number of persons buried in each grave. It has been<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sized th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>y are single graves, given <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> c<strong>is</strong>ts. But<br />

Fig. 3 Li Muri burial circles.<br />

25

Fig. 4 Li Muri burial circles.<br />

we cannot overlook <strong>the</strong> possibility th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> grave may have contained<br />

more than one body since we know nothing of how <strong>the</strong> dead were<br />

buried. Nor do we know if <strong>the</strong> body was buried whole (primary burial)<br />

or if <strong>the</strong> skeleton was placed <strong>the</strong>re following <strong>the</strong> falling away of <strong>the</strong><br />

flesh (secondary burial).<br />

The finding of pebbles with residues of red ochre in <strong>the</strong> graves has<br />

also led to <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>s<strong>is</strong> th<strong>at</strong> th<strong>is</strong> may have been used to paint <strong>the</strong> body<br />

of <strong>the</strong> deceased: red <strong>is</strong> in fact <strong>the</strong> colour of blood and regener<strong>at</strong>ion; its<br />

use in Neolithic Sardinian graves has been widely documented.<br />

Of special importance are <strong>the</strong> objects included in <strong>the</strong> grave goods<br />

th<strong>at</strong> accompanied <strong>the</strong> dead in <strong>the</strong>ir tombs. Finely-made stone artefacts<br />

showing signs of skilful workmanship have been found: a soapstone<br />

cup with two splayed handles and <strong>the</strong> bottom with a ring in relief; slender<br />

flint blades, triangular h<strong>at</strong>chets made of hard, smoo<strong>the</strong>d stone,<br />

round pommels with holes of uncertain use, perhaps weapons in handto-hand<br />

comb<strong>at</strong> or insignia; finally, a large number of soapstone beads<br />

in <strong>the</strong> form of small olives, o<strong>the</strong>rs spherical and d<strong>is</strong>c-shaped.<br />

Minute pieces of pottery made of mixed clay with no decor<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

26

Fig. 5<br />

Li Muri burial<br />

circles: spherical<br />

pommels<br />

made of green<br />

and blue<br />

ste<strong>at</strong>ite, from<br />

Grave IV.<br />

were also found. Of all <strong>the</strong> objects described, <strong>the</strong> small soapstone cup<br />

deserves special <strong>at</strong>tention since it has much in common with similar<br />

stone objects found on Crete, from which its import<strong>at</strong>ion to Sardinia<br />

has been hypo<strong>the</strong>sized. O<strong>the</strong>r objects suggesting an origin from abroad<br />

are <strong>the</strong> spheroid pommels since <strong>the</strong>y have been found on Crete and in<br />

An<strong>at</strong>olia as well as on <strong>the</strong> Italian and Iberian peninsulas and France. In<br />

contexts of <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture in Sardinia, besides <strong>the</strong> soapstone cup,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> a widespread use of stone objects in <strong>the</strong> L<strong>at</strong>e Neolithic.<br />

As concerns architecture, <strong>the</strong> <strong>monument</strong>s most similar to <strong>the</strong> Li<br />

Muri necropol<strong>is</strong> are to be found in Corsica where <strong>the</strong> ‘coffre’ tombs <strong>at</strong><br />

Tivolaggiu (Porto Vecchio), Vasacciu, Monte Rotundu (Sotta) and<br />

Caleca (Levì) yielded grave goods with a wealth of Sardinian obsidian<br />

objects and o<strong>the</strong>r stone objects confirming <strong>the</strong> close rel<strong>at</strong>ionship<br />

between Gallura and sou<strong>the</strong>rn Corsica between <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> 4th and<br />

<strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> 3rd millennia.<br />

If on <strong>the</strong> one hand <strong>the</strong> overall remains of Li Muri allow inclusion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> cultural phenomenon of <strong>the</strong> grave circles in a context of a widespread<br />

circul<strong>at</strong>ion of goods and ideas, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand <strong>the</strong> m<strong>at</strong>erial<br />

d<strong>at</strong>a are not sufficient to allow <strong>the</strong> drawing of a picture of <strong>the</strong> economy<br />

and society of <strong>the</strong> period.<br />

We do not even have an idea of <strong>the</strong> dwellings of <strong>the</strong> Gallura group<br />

in question; some believe <strong>the</strong>y may have been in <strong>the</strong> many tafoni pre-<br />

27

Fig. 6 Macciunitta burial circle.<br />

sent in <strong>the</strong> surrounding mountains. On th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong>sue, it <strong>is</strong> to be said th<strong>at</strong><br />

recent d<strong>is</strong>coveries have ra<strong>is</strong>ed new questions since <strong>the</strong> remains of <strong>the</strong><br />

floors of huts belonging to <strong>the</strong> Ozieri culture have been found <strong>at</strong> a<br />

place known as Pilastru, about six hundred metres as <strong>the</strong> crow flies<br />

from <strong>the</strong> necropol<strong>is</strong>. It now remains to be seen to wh<strong>at</strong> extent th<strong>is</strong> village<br />

can be connected to <strong>the</strong> necropol<strong>is</strong>.<br />

2<br />

Macciunitta<br />

ANGELA ANTONA RUJU<br />