Bare nouns and the status of determiners in - University of Manitoba

Bare nouns and the status of determiners in - University of Manitoba

Bare nouns and the status of determiners in - University of Manitoba

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

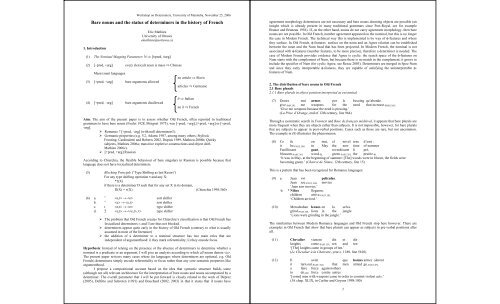

Workshop on Determ<strong>in</strong>ers, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Manitoba</strong>, November 25, 2006<br />

<strong>Bare</strong> <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> French<br />

1. Introduction<br />

Eric Mathieu<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ottawa<br />

emathieu@uottawa.ca<br />

(1) The Nom<strong>in</strong>al Mapp<strong>in</strong>g Parameter: N ⇒ [±pred, ±arg]<br />

(2) [–pred, +arg] every (lexical) noun is mass ⇒ Ch<strong>in</strong>ese<br />

Mass/count languages<br />

(3) [+pred, +arg] bare arguments allowed<br />

(4) [+pred, –arg] bare arguments disallowed<br />

no article ⇒ Slavic<br />

articles ⇒ Germanic<br />

∂ ⇒ Italian<br />

no ∂ ⇒ French<br />

Aim: The aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present paper is to assess whe<strong>the</strong>r Old French, <strong>of</strong>ten reported <strong>in</strong> traditional<br />

grammars to have bare <strong>nouns</strong> (Foulet 1928, Moignet 1973), was [–pred, +arg], [+pred, +arg] or [+pred,<br />

-arg].<br />

Romance ? [+pred, –arg] (with null <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>?).<br />

Germanic properties (e.g. V2, Adams 1987, among many o<strong>the</strong>rs; Stylistic<br />

Front<strong>in</strong>g, Card<strong>in</strong>aletti <strong>and</strong> Roberts 2002, Dupuis 1989, Mathieu 2006b; Quirky<br />

subjects, Mathieu 2006a; transitive expletive constructions <strong>and</strong> object shift,<br />

Mathieu 2006c).<br />

[+pred, +arg] Russian<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Chierchia, <strong>the</strong> flexible behaviour <strong>of</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars <strong>in</strong> Russian is possible because that<br />

language does not have lexicalized <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>.<br />

(5) Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple (‘Type Shift<strong>in</strong>g as last Resort’)<br />

For any type shift<strong>in</strong>g operation τ <strong>and</strong> any X:<br />

*τ(X)<br />

if <strong>the</strong>re is a determ<strong>in</strong>er D such that for any set X <strong>in</strong> its doma<strong>in</strong>,<br />

D(X) = τ(X) (Chierchia 1998:360)<br />

(6) a.<br />

∩<br />

→ sort shifter<br />

b.<br />

∪<br />

→ sort shifter<br />

c. ι → type shifter<br />

d. ∃ → type shifter<br />

The problem that Old French creates for Chierchia’s classification is that Old French has<br />

lexicalized <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>: ι <strong>and</strong> ∃ are thus not blocked.<br />

<strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> appear quite early <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Old French (contrary to what is usually<br />

assumed <strong>in</strong> most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature)<br />

<strong>the</strong> addition <strong>of</strong> a determ<strong>in</strong>er to a nom<strong>in</strong>al structure has two ma<strong>in</strong> roles that are<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> argumenthood: i) <strong>the</strong>y mark referentiality; ii) <strong>the</strong>y encode focus.<br />

Hypo<strong>the</strong>sis: Instead <strong>of</strong> rely<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> presence or <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> to determ<strong>in</strong>e whe<strong>the</strong>r a<br />

nom<strong>in</strong>al is a predicate or an argument, I will give an analysis accord<strong>in</strong>g to which all <strong>nouns</strong> denote .<br />

The present paper reviews many cases where (<strong>in</strong> languages where <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> are optional, e.g. Old<br />

French) <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> simply encode referentiality or focus ra<strong>the</strong>r than any core semantic properties like<br />

argumenthood.<br />

I propose a compositional account based on <strong>the</strong> idea that syntactic structure builds some<br />

(although not all) relevant architecture for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> bare <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>nouns</strong> accompanied by a<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>er. The overall parameter that I will be put forward is closely related to <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> Déprez<br />

(2005), Delfitto <strong>and</strong> Schroten (1991) <strong>and</strong> Bouchard (2002, 2003) <strong>in</strong> that it states that if <strong>nouns</strong> have<br />

agreement morphology <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> are not necessary <strong>and</strong> bare <strong>nouns</strong> denot<strong>in</strong>g objects are possible (an<br />

<strong>in</strong>sight which is already present <strong>in</strong> many traditional grammars s<strong>in</strong>ce Port-Royal, see for example<br />

Brunot <strong>and</strong> Bruneau 1956). If, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>nouns</strong> do not carry agreement morphology, <strong>the</strong>n bare<br />

<strong>nouns</strong> are not possible. In Old French, number agreement appeared on <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al, but this is no longer<br />

<strong>the</strong> case <strong>in</strong> Modern French. The technical way this is implemented is by way <strong>of</strong> φ-features <strong>and</strong> where<br />

<strong>the</strong>y surface. In Old French, φ-features surface on <strong>the</strong> noun <strong>and</strong> an Agree relation can be established<br />

between <strong>the</strong> noun <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Num head that has been projected. In Modern French, <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al is not<br />

associated with φ-features (number features, to be more precise), <strong>the</strong>refore a determ<strong>in</strong>er is needed. The<br />

case <strong>of</strong> Modern French provides evidence that Agree is cyclic: <strong>the</strong> search space <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> φ-features on<br />

Num starts with <strong>the</strong> complement <strong>of</strong> Num, but because <strong>the</strong>re is no match <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> complement, it grows to<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> specifier <strong>of</strong> Num (for cyclic Agree, see Rezac 2003). Determ<strong>in</strong>ers are merged <strong>in</strong> Spec-Num<br />

<strong>and</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y carry <strong>in</strong>terpretable φ-features, <strong>the</strong>y are capable <strong>of</strong> satisfy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> un<strong>in</strong>terpretable φfeatures<br />

<strong>of</strong> Num.<br />

2. The distribution <strong>of</strong> bare <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> Old French<br />

2.1 <strong>Bare</strong> plurals<br />

2.1.1 <strong>Bare</strong> plurals <strong>in</strong> object position <strong>in</strong>terpreted as existential<br />

(7) Donez moi armes por le beso<strong>in</strong>g qu’abonde.<br />

give.IMP.2PL me weapons for <strong>the</strong> need that <strong>in</strong>crease.PRES.3SG<br />

‘Give me weapons because <strong>the</strong> need is press<strong>in</strong>g.’<br />

(La Prise d’Orange, end <strong>of</strong> 12th century, l<strong>in</strong>e 964)<br />

Through a systematic search <strong>in</strong> Frantext <strong>and</strong> Base de français médiéval, it appears that bare plurals are<br />

more frequent when <strong>the</strong>y are objects ra<strong>the</strong>r than subjects. It is not impossible, however, for bare plurals<br />

that are subjects to appear <strong>in</strong> post-verbal positions. Cases such as those are rare, but not uncommon.<br />

The example <strong>in</strong> (8) illustrates <strong>the</strong> phenomenon.<br />

(8) Ce fu en mai, el novel tens d’esté :<br />

it be.PAST.3SG <strong>in</strong> May <strong>the</strong> new time <strong>of</strong>-summer<br />

Fueillissent gaut, reverdissent li pré,<br />

blossom.PAST.3PL wood.PL green.PAST.3PL <strong>the</strong> prairie.PL<br />

‘It was <strong>in</strong> May, at <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> summer: [The] woods were <strong>in</strong> bloom, <strong>the</strong> fields were<br />

becom<strong>in</strong>g green.’ (Charroi de Nîmes, 12th century, l<strong>in</strong>e 15)<br />

This is a pattern that has been recognized for Romance languages:<br />

(9) a. Juan vió películas.<br />

Juan see.PAST .3SG movies<br />

‘Juan saw movies.’<br />

b. * Niños llegaron.<br />

children arrive.PAST.3PL<br />

‘Children arrived.’<br />

(10) Merodeaban leones en la selva.<br />

gr<strong>in</strong>d.PAST.3PL lions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> jungle<br />

‘Lions were gr<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> jungle.’<br />

The similarities between Modern Romance languages <strong>and</strong> Old French stop here however. There are<br />

examples <strong>in</strong> Old French that show that bare plurals can appear as subjects <strong>in</strong> pre-verbal positions after<br />

all.<br />

(11) Chevalier vienent dis et dis<br />

knights come.PAST.3PL ten <strong>and</strong> ten<br />

‘[The] knights came <strong>in</strong> groups <strong>of</strong> ten.’<br />

(Le Chevalier à la Charrette, year c. 1180, l<strong>in</strong>e 5610)<br />

(12) Il av<strong>in</strong>t que homes armez alerent<br />

it turn.out.PAST.3SG that men armed go.PAST.3PL<br />

a faire force aga<strong>in</strong>st o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

to do.INF force contre autres<br />

‘[some] men with weapons came <strong>in</strong> order to commit violent acts.’<br />

(JA chap. XLIX, <strong>in</strong> Carlier <strong>and</strong> Goyens 1998:100)<br />

2

(13) La voie commença a estrecier et raim furent bas<br />

<strong>the</strong> path beg<strong>in</strong>.PAST.3SG to shr<strong>in</strong>k.INF <strong>and</strong> branches be.PAST.3PL low<br />

‘The path began to get narrower <strong>and</strong> [<strong>the</strong>] branches were low.’<br />

(La fille du comte Pontieu, 13th century, p. 158)<br />

It never<strong>the</strong>less appears that <strong>the</strong>se bare plurals are possible <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> subject position because <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

specific: <strong>the</strong>y refer back to an entity already <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> discourse or <strong>the</strong>y are identified via socalled<br />

accommodation.<br />

2.1.2 <strong>Bare</strong> plurals as k<strong>in</strong>ds<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r major difference between Modern Romance languages (except Portuguese) <strong>and</strong> Old French is<br />

that <strong>in</strong> Modern Romance languages bare plurals are not compatible with predicates that select k<strong>in</strong>ds or<br />

with i-<strong>in</strong>dividual predicates (Defiltto 2002, Dobrovie-Sor<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Laca 2003, Longobardi 2001).<br />

(14) Dames en canbres fuit et het.<br />

ladies <strong>in</strong> chambers flee.PRES.3SG <strong>and</strong> hate.PRES.3SG<br />

‘He hates ladies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir chambers <strong>and</strong> keeps away from <strong>the</strong>m.’<br />

(Lai de Narcisse, year 1170, l<strong>in</strong>e 120)<br />

(15) a. Et sachiez que ostour sont de .iij. manieres :<br />

<strong>and</strong> know that vultures be.PRES.3PL <strong>of</strong> three k<strong>in</strong>ds<br />

petit, grant, meien.<br />

small big average<br />

‘Know that vultures come <strong>in</strong> three k<strong>in</strong>ds: small, big, average.’<br />

(Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, CXLVIII De toutes manieres de<br />

Ostours, p. 197)<br />

b. Peisson sont sanz nombre<br />

fishes be.PAST.3PL without number<br />

‘Fishes are rare.’<br />

(Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, CXXXI, Ci comence de la nature des<br />

Animaus et premierement des poissons, p. 184)<br />

From this po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view, Old French fits quite nicely with Chierchia’s (1998) typology. The fact that <strong>in</strong><br />

Italian, Spanish <strong>and</strong> Romanian, (unmodified) bare plurals appear not to be able to comb<strong>in</strong>e with<br />

predicates that select k<strong>in</strong>ds or with i-<strong>in</strong>dividual predicates has been taken to be problematic for<br />

Chierchia’s <strong>the</strong>ory. Because <strong>of</strong> this, Dobrovie-Sor<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Laca (2003), Dobrovie-Sor<strong>in</strong>, Bleam <strong>and</strong><br />

Esp<strong>in</strong>al (2005) thus argue for an analysis accord<strong>in</strong>g to which bare plurals denote a property. On this<br />

view, <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d or generic read<strong>in</strong>g is not <strong>the</strong> basic <strong>in</strong>terpretation from which o<strong>the</strong>rs are derived contrary<br />

to what Carlson (1977) <strong>and</strong> Chierchia (1998) have argued.<br />

2.2 <strong>Bare</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars<br />

2.2.1 <strong>Bare</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars as k<strong>in</strong>ds<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r major difference between Romance languages on <strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Old French on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

(16) Taupe est une diverse beste (k<strong>in</strong>d)<br />

mole be.PRES.3SG a diverse animal<br />

‘The mole is a diverse animal.’ (Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, CC, De la Taupe, p. 252)<br />

(17) Ech<strong>in</strong>us est uns petit poissons de mer (subk<strong>in</strong>d)<br />

see urch<strong>in</strong> be.PRES.3SG a little fish <strong>of</strong> sea<br />

‘The sea urch<strong>in</strong> is a small fish from <strong>the</strong> sea.’<br />

(Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, CXXXI, Ci comence de la nature des Animaus et<br />

premierement des poissons, p. 184)<br />

These examples are particularly problematic for Chierchia’s (1998), s<strong>in</strong>ce accord<strong>in</strong>g to him <strong>in</strong> a<br />

language with a s<strong>in</strong>gular/plural contrast, bare s<strong>in</strong>gular <strong>nouns</strong> are not attested – to quote him: ‘In both<br />

Germanic <strong>and</strong> Romance bare s<strong>in</strong>gular arguments are totally impossible (if <strong>the</strong> noun is not mass)’ p.<br />

341. Moreover, bare s<strong>in</strong>gular <strong>nouns</strong> need to project a def<strong>in</strong>ite determ<strong>in</strong>er <strong>in</strong> order to refer to k<strong>in</strong>ds (e.g.<br />

<strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Modern French, Italian, English, etc.). This claim is falsified by <strong>the</strong> data <strong>in</strong> (16). Dayal’s<br />

solution? (atomic k<strong>in</strong>ds).<br />

The problem <strong>in</strong> turn with this idea is that <strong>in</strong> Old French <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er with bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars<br />

denot<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>ds appears completely optional as we shall see <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> next section. This is a situation which<br />

is entirely parallel to <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gular mass <strong>nouns</strong>. These can appear with or without a determ<strong>in</strong>er as<br />

<strong>the</strong> contrast between (18a) <strong>and</strong> (18b) illustrates.<br />

3<br />

(18) a. Jo vos durrai or e argent asez<br />

I you give.FUT.1SG gold <strong>and</strong> silver enough<br />

‘I will give much gold <strong>and</strong> silver.’ (La Chanson de Rol<strong>and</strong>, year 1080, l<strong>in</strong>e 75)<br />

b. De lur tresors prenent l’or e l’argent<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir treasures take.PRES.3PL <strong>the</strong>-gold <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>-silver<br />

‘They take gold <strong>and</strong> silver from <strong>the</strong>ir treasures.’<br />

(La vie de Sa<strong>in</strong>t Alexis, year 1050, l<strong>in</strong>e 526)<br />

2.2.2 <strong>Bare</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars <strong>in</strong>terpreted generically<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>in</strong> Old French, naturally <strong>the</strong>y can receive a generic<br />

read<strong>in</strong>g as witnessed by <strong>the</strong> examples <strong>in</strong> (19) – at least, if one follows <strong>the</strong> Carlson/Chierchia view <strong>of</strong><br />

generics.<br />

(19) a. Quant hom est viex, vet a bastons;<br />

when man.SG be.PRES.3SG old carry.3SG to cane<br />

‘When [a] man is old, it carries a cane.’<br />

(Le Roman de Thèbes, year 1150, l<strong>in</strong>e 2933)<br />

b. Com chiens abaie par costume ;<br />

like dog.SG bark.PRES.3SG by habit<br />

‘As <strong>the</strong> dog barks by habit.’<br />

(Enéas, year 1150, l<strong>in</strong>e 2579)<br />

c. Cocodrille est uns animaus a .iiij. piez et de jaune color<br />

crocodile.SG be.PRES.3SG a animal at four feet <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> yellow colour<br />

‘The crocodile is a four-legged animal <strong>and</strong> is yellow.’<br />

(Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, V, Dou cocodrille, p.184)<br />

2.2.3 <strong>Bare</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars as def<strong>in</strong>ites<br />

In (20) by <strong>the</strong> time filie ‘daughter’ is used, a rich context is available, one <strong>in</strong> which moyler ‘wife’ has<br />

been mentioned, <strong>the</strong>refore filie can be used without a determ<strong>in</strong>er.<br />

(20) or uolt que prenget moyler a son vivant ;<br />

however want.PRES.3SG that take.PRES.3SG wife at his liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dunc li acatet filie d’un noble franc<br />

thus him.DAT buy.PRES3SG daughter <strong>of</strong>-a noble man<br />

‘he wants him to take [a] wife dur<strong>in</strong>g his lifetime; so he buys him [<strong>the</strong>] daughter <strong>of</strong> a<br />

nobleman.’ (Alex v. 39-40, Epste<strong>in</strong>, 1994, 68)<br />

In (21) it is clear from <strong>the</strong> context that <strong>the</strong> viol<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> bow belong to Nicolette. Therefore, <strong>the</strong> article<br />

can be dropped.<br />

(21) Es vous Nichole au peron,<br />

<strong>and</strong> here Nichole at-<strong>the</strong> steps<br />

trait vïele, trait arçon<br />

take.out.PRES.3SG viol<strong>in</strong> take.out.PRES.3SG bow<br />

‘There is Nicolette on <strong>the</strong> steps, she takes out [her] viol<strong>in</strong>, takes out [her] bow.’<br />

(Aucass<strong>in</strong> et Nicolette, early 13th centuy, XXXIX, 11-12, <strong>in</strong> Epste<strong>in</strong>, )<br />

Cases where <strong>the</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gular is def<strong>in</strong>ite, but does not refer a particular entity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> discourse are also<br />

possible. This is when <strong>the</strong> substantive is sufficiently identified by <strong>the</strong> receiver as unique, perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to<br />

one type sufficiently def<strong>in</strong>ed by a usual employment as <strong>in</strong> (22).<br />

(22) Deus, reis de glorie…<br />

God k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> glory<br />

Cel e terre fesis, e cele mer,<br />

this.one <strong>and</strong> earth do.PAST.3SG <strong>and</strong> heaven sea<br />

Soleil e lune, tut ço a com<strong>and</strong>é<br />

sun <strong>and</strong> moon all this have.3SG ordered<br />

‘God, k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> glory who has created <strong>the</strong> heavens, <strong>the</strong> earth, <strong>the</strong> sea, <strong>the</strong> sun <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> moon has<br />

ordered all this.’ (Guillaume, 12 th century, 804-805)<br />

2.2.4 <strong>Bare</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars <strong>in</strong>terpreted existentially<br />

While it is possible <strong>in</strong> Old French for bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars to be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as def<strong>in</strong>ites, <strong>the</strong> opposite use <strong>of</strong><br />

bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars, i.e. as <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ites, is also possible. In (23), <strong>the</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gular is <strong>in</strong>terpreted existentially.<br />

4

(23) Ele respont : ‘Sire, mon pere<br />

she reply.PRES.3SG Sir, my fa<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Prist fenme aprés la mort ma mere …<br />

take.PAST.3SG wife after <strong>the</strong> death my mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

‘She replies : Sir, my fa<strong>the</strong>r took [a] wife [i.e. married] after <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> my mo<strong>the</strong>r.’<br />

(L’âtre périlleux, roman de la Table Ronde, year 1268, l<strong>in</strong>es 1189-1190)<br />

Low scope:<br />

(24) n i remest palie ne neul ornement<br />

not <strong>the</strong>re rema<strong>in</strong>.PAST.3SG tapestry nor none ornamen<br />

‘<strong>the</strong>re rema<strong>in</strong>ed no tapestry nor any ornament.’<br />

(La Vie de Sa<strong>in</strong>t Alexis, year 1050, l<strong>in</strong>e 24, <strong>in</strong> Epste<strong>in</strong> p. 66)<br />

It is not <strong>the</strong> case that <strong>the</strong>re rema<strong>in</strong>ed a tapestry <strong>and</strong> an ornament.<br />

*There is a tapestry <strong>and</strong> an ornament <strong>and</strong> it is not <strong>the</strong> case that <strong>the</strong>re rema<strong>in</strong>ed any.<br />

<strong>Bare</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars typically occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> scope <strong>of</strong> an operator. Apart from negative contexts such as <strong>the</strong> one<br />

described <strong>in</strong> (24), bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars <strong>in</strong>terpreted as low-scope <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ites can appear <strong>in</strong>terrogative (25),<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>tical (26) <strong>and</strong> comparative environments (27).<br />

(25) Avés vous dont borse trovée ?<br />

have.2PL you thus purse found<br />

‘So have you found [any] purse?’ (<strong>in</strong> Foulet 1928 :58)<br />

(26) Se vos volez ne chastel ne cité<br />

if you want.PRES.2PL or castle or city<br />

Ne tor ne vile, donjon ne fermeté<br />

or tower or town, donjon or fortress<br />

Ja vos sera otroié et graé<br />

this you be.FUT.3SG given <strong>and</strong> agreed<br />

‘If you want [a] castle or [a] city or [a] tower or [a] town, [a] dungeon or [a] fortress, this will<br />

be granted <strong>and</strong> given to you.’ (Le Charroi de Nîmes, 12th century, l<strong>in</strong>es 471-473)<br />

(27) Plus est isnels que n’est oisel ki volet<br />

more be.PRES.3SG fast than NE-be.PRES.3SG bird that fly.PRES.3SG<br />

‘He is faster than [a] bird that flies.’ (La Chanson de Roll<strong>and</strong>, year 1080, l<strong>in</strong>e 1616)<br />

The above facts lead to <strong>the</strong> conclusion that Old French cannot be assimilitated with Modern Romance<br />

languages. Could Old French <strong>the</strong>refore be assimilated with Ch<strong>in</strong>ese type languages?<br />

(28) cheval → chevaulx<br />

(29) trois foiz l’apele par son nom<br />

three times him-call.PRES.3SG by his name<br />

‘He/she calls him by his name.’ (Enéas, year 1150, l<strong>in</strong>e 2168)<br />

In view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> facts <strong>in</strong>troduced above, one option worth explor<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong> idea that Old French is like<br />

Russian, i.e. a language with a mass/count dist<strong>in</strong>ction <strong>and</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gular/plural contrast with no classifier<br />

system, yet with <strong>the</strong> general availability <strong>of</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars. As a putative [+arg;+pred] language, it is<br />

predicted that Old French tolerate bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars <strong>in</strong> predicate positions. The prediction is borne out as<br />

example (30) shows.<br />

(30) Bien i pert que vos estes fame<br />

well <strong>the</strong>re appear.PRES.3SG that you be.PRES.2PL woman<br />

‘One can tell very well that you are a woman.’<br />

(Yva<strong>in</strong>, Le Chevalier au Lion, year 1179, l<strong>in</strong>e 1654, dans Joly 1998:257)<br />

3. The use <strong>of</strong> articles <strong>in</strong> Old French<br />

It is generally claimed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature that <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> developed slowly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> French. The<br />

problem with this view is that <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite article surfaces much earlier than commonly believed (<strong>the</strong>re<br />

thus must be a mismatch between <strong>the</strong> prescriptive description <strong>of</strong> grammarians <strong>and</strong> actual use). To<br />

illustrate, <strong>in</strong> La Vie de Sa<strong>in</strong>t Alexis, a very early text dated 1050, hardly any bare nom<strong>in</strong>als are<br />

available. Instead, most <strong>nouns</strong> appear with a determ<strong>in</strong>er.<br />

5<br />

‘L’expression de l’article dans ce vers prouve qu’il n’y a guère de ‘règle’ absolument<br />

rigoureuse dans la syntaxe de l’ancienne langue.’ (Raynaud de Lage, Guy 1983 p. 46). ‘Il<br />

arrive que les poètes du moyen âge semblent employer <strong>in</strong>différemment le nom sans article,<br />

le nom précédé de l’article et le nom précédé d’un démonstratif.’ (Brunot <strong>and</strong> Bruneau<br />

1956 p. 218). The free variation between bare <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>and</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>als with a determ<strong>in</strong>er is also<br />

reported by Carlier <strong>and</strong> Goyens (1998).<br />

In La Cantilene de Sa<strong>in</strong>te Eulalie, a text said to have been written around 878, an even earlier date,<br />

presence <strong>and</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite determ<strong>in</strong>er alternate quite freely. In (31) a determ<strong>in</strong>er is used<br />

because <strong>the</strong> young girl has been discussed at great length <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> previous verses.<br />

(31) Niule cose non la pouret omque pleier<br />

no th<strong>in</strong>g not her can.PAST.3SG never give.up.INF<br />

La polle sempre non amast lo Deo menestier<br />

<strong>the</strong> young. girl always not love.PAST.3SG <strong>the</strong> God service<br />

‘Noth<strong>in</strong>g could make <strong>the</strong> young girl not appreciate <strong>the</strong> service God.’<br />

(La Cantilene de Sa<strong>in</strong>te Eulalie, year 878, l<strong>in</strong>es 8-10)<br />

This is a case, however, that does not necessarily go aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> Chierchia<br />

(1998), s<strong>in</strong>ce it could be argued that <strong>the</strong> choice between <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> a bare noun <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> a noun<br />

with a determ<strong>in</strong>er is between <strong>the</strong> non-referential/non-specific versus referential/specific use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

noun. This is <strong>the</strong> view Baker (2003) takes on <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>: <strong>the</strong>ir purpose is not to convert<br />

<strong>nouns</strong> <strong>in</strong>to arguments, but ra<strong>the</strong>r to contribute to <strong>the</strong> organization <strong>of</strong> discourse. Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> logic <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er thus expresses more than ι. This is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> what is<br />

proposed by Krifka (2003) for <strong>the</strong> optionality between bare <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> some <strong>in</strong> English (Dogs<br />

are bark<strong>in</strong>g versus Some dogs are bark<strong>in</strong>g; I drank milk versus I drank some milk). The difference that<br />

<strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er some makes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> structure is that it <strong>in</strong>troduces a choice function, thus allow<strong>in</strong>g for<br />

wide scope <strong>in</strong>terpretations.<br />

There are none<strong>the</strong>less cases where <strong>the</strong> addition <strong>of</strong> a determ<strong>in</strong>er is completely unexpected.<br />

(32) Ad une spede li roveret tolir lo chieef.<br />

with a spear her order.PAST.3SG cut.INF <strong>the</strong> head<br />

‘He ordered for her head to be cut with a spear.’<br />

(La Cantilene de Sa<strong>in</strong>te Eulalie, year 878, l<strong>in</strong>e 22)<br />

(33) Qued auuisset de nos Christus mercit<br />

for have.SUBJ.3SG <strong>of</strong> us Christ mercy<br />

Post la mort et a lui nos laist venir Par souue clementia.<br />

after <strong>the</strong> death <strong>and</strong> to him us let.pres.3SG come.INF by his clemence<br />

‘In order for Christ to have mercy on us after death <strong>and</strong> for him to let us come to him thanks to<br />

his clemence.’ (La Cantilene de Sa<strong>in</strong>te Eulalie, year 878, l<strong>in</strong>es 27-29)<br />

Here, I would like to follow a series <strong>of</strong> work by Richard Epste<strong>in</strong> (1993, 1994, 1995) who argues that, <strong>in</strong><br />

addition to <strong>the</strong>ir referential use, <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> <strong>in</strong> Old French can be used to express po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view.<br />

Epste<strong>in</strong> works with<strong>in</strong> a cognitive approach, but his idea <strong>of</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view can easily be translated as<br />

what is known as ‘focus’ <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r frameworks. When <strong>the</strong> speaker wants to <strong>in</strong>sist on <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> a<br />

particular referent, a determ<strong>in</strong>er is added so that <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al is no longer bare.<br />

(34) Et dit li cuens: ‘Vos dites voir, beau niés ;<br />

<strong>and</strong> say.PRES.3SG <strong>the</strong> count you say.PRES.2PL true dear nephew<br />

La leauté doit l’en toz jorz amers.’<br />

<strong>the</strong> loyalty must.PRES.3SG it-one all days love.PRES.3SG<br />

‘The count replied: ‘You speak <strong>the</strong> truth, dear nephew, one must always love loyalty.’<br />

(Le Chevalier à la Charrette, year c. 1180, l<strong>in</strong>es 441-442)<br />

(35) Envie lor fait grant contraire<br />

envy <strong>the</strong>m.DAT make.PRES.3SG big contrary<br />

‘Envy is not good for <strong>the</strong>m.’ (Eracle, year 1180, l<strong>in</strong>e 1061)<br />

It appears that it is <strong>in</strong> post-verbal positions that <strong>the</strong> addition <strong>of</strong> a determ<strong>in</strong>er is crucial if one wants to<br />

focalize a nom<strong>in</strong>al. This idea may expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that a bare s<strong>in</strong>gular can be used generically with or<br />

without a determ<strong>in</strong>er <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same sentence as <strong>the</strong> example <strong>in</strong> (36) shows.<br />

6

(36) Fenme ne puet tant amer l’oume con li hom<br />

woman not can.PRES.3SG as.much love.INF <strong>the</strong>-man as <strong>the</strong> man<br />

fait le fenme<br />

do.PRES.3SG <strong>the</strong> woman<br />

‘Woman cannnot love man as much as man loves woman.’ (Aucass<strong>in</strong> et Nicolette, l<strong>in</strong>es 21-22)<br />

Be<strong>in</strong>g a general statement, suppose <strong>the</strong> speaker wants to <strong>in</strong>sist on all nom<strong>in</strong>als present <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sentence.<br />

A determ<strong>in</strong>er is needed <strong>in</strong> object positions (<strong>the</strong> first <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>of</strong> ‘man’ <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> second <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>of</strong><br />

‘woman’), but is not crucial <strong>in</strong> subject positions: no determ<strong>in</strong>er accompanies <strong>the</strong> first <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>of</strong><br />

‘woman’. Yet, <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> a determ<strong>in</strong>er with <strong>the</strong> second occurrence <strong>of</strong> ‘man’ is tolerated.<br />

Epste<strong>in</strong> is not <strong>the</strong> first to notice <strong>the</strong> expressive role <strong>of</strong> <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> <strong>in</strong> Old French. Brunot et<br />

Bruneau (1956) note that: ‘l’article peut avoir une valeur expressive’ (p. 218). They give <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

example where articles are used <strong>in</strong> an o<strong>the</strong>rwise prototypical environment where articles would be<br />

dropped, i.e. an enumeration context.<br />

(37) Quoi?...nostre avoir avés vous parti, dont nous avons souffert<br />

what our stock have.3PL you shared <strong>of</strong>-which we have.1PL suffered<br />

les gr<strong>and</strong>es pa<strong>in</strong>es et les grans travaus, les fa<strong>in</strong>s et les sois et les<br />

<strong>the</strong> big pa<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> big works <strong>the</strong> h<strong>in</strong>gers <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> thirst <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

frois et les caus, si l’avés parti sans nous?<br />

colds <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> hots thus it-have.2PL shared without us<br />

‘What? you shared our goods, this stock for which we have suffered great pa<strong>in</strong>, for which we<br />

have worked so much, for which we went through hunger <strong>and</strong> thirst, cold <strong>and</strong> heat, you shared it<br />

without us?’ (La Conquête de Constant<strong>in</strong>ople, c. 1212, p.100, l<strong>in</strong>es 12-13), <strong>in</strong> Brunot <strong>and</strong><br />

Bruneau 1956:218)<br />

It must be noted that, very early on, it is also possible for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite determ<strong>in</strong>er to appear with bare<br />

<strong>nouns</strong> that are <strong>in</strong>terpreted generically. The follow<strong>in</strong>g example is from La Chanson de Rol<strong>and</strong>, a text<br />

dated 1080.<br />

(38) Plus est isnels que uns falcuns<br />

more be.PRES.3SG quick than a falcon<br />

‘He is quicker than a falcon.’ (La Chanson de Rol<strong>and</strong>, year 1080, l<strong>in</strong>e 1874)<br />

German is ano<strong>the</strong>r language that allows bare <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite plurals for k<strong>in</strong>d reference. Krifka et al. (1995)<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduce <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g example.<br />

(39) (Die) P<strong>and</strong>abären s<strong>in</strong>d vom Aussterben bedroht.<br />

<strong>the</strong> p<strong>and</strong>as be.PRES.3PL <strong>of</strong> ext<strong>in</strong>ction threatened<br />

‘P<strong>and</strong>as are fac<strong>in</strong>g ext<strong>in</strong>ction.’<br />

German is also like Old French <strong>in</strong> allow<strong>in</strong>g bare <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite mass terms for k<strong>in</strong>d reference. Compare<br />

(18) with (40).<br />

(40) (Das) Gold steigt im Preis.<br />

<strong>the</strong> gold <strong>in</strong>crease.PRES.3SG <strong>in</strong> price<br />

‘Gold is gett<strong>in</strong>g more expensive.’<br />

The reason why I mention German at this po<strong>in</strong>t is because Old French can be grouped with o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

languages (like German) which, unless given additional explanation, are a problem for <strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> Chierchia (1998). In order to account for <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> data from German <strong>in</strong>troduced above<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> order thus to save <strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, Dayal (2004) makes a big deal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that German<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gular nom<strong>in</strong>als must never<strong>the</strong>less, as shown by <strong>the</strong> examples <strong>in</strong> (41), be accompanied by a<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>er.<br />

(41) a. Der P<strong>and</strong>abär / *P<strong>and</strong>abär ist vom Aussterben bedroht.<br />

<strong>the</strong> p<strong>and</strong>a / *p<strong>and</strong>a be.PRES.3SG <strong>of</strong> ext<strong>in</strong>ction threatened<br />

‘The P<strong>and</strong>a is fac<strong>in</strong>g ext<strong>in</strong>ction.’<br />

b. Der Hund /*Hund bellt.<br />

<strong>the</strong> dog/*dog bark.PRES.3SG<br />

‘The dog is bark<strong>in</strong>g.’<br />

The dist<strong>in</strong>ction between <strong>the</strong> canonical <strong>and</strong> non-canonical functions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite determ<strong>in</strong>er that<br />

Dayal <strong>in</strong>troduces to account for <strong>the</strong> German facts is ra<strong>the</strong>r ad hoc, but <strong>the</strong> bottom l<strong>in</strong>e is this. In a<br />

7<br />

language where <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> are lexicalized, ∩ is still blocked <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars. This is taken<br />

to be <strong>the</strong> default/canonical case. The problem, however, is that <strong>in</strong> Old French k<strong>in</strong>d s<strong>in</strong>gulars can<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itely be bare as <strong>the</strong> example <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> (16).<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>se generalizations appear to be all that is needed to account for <strong>the</strong> cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic<br />

facts, <strong>the</strong> two generalizations <strong>in</strong> fact collapse <strong>in</strong> view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Old French data <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> this paper.<br />

First, bare s<strong>in</strong>gular terms <strong>in</strong> Old French can appear without a determ<strong>in</strong>er on <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d read<strong>in</strong>g despite <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that a bare s<strong>in</strong>gular nom<strong>in</strong>al (<strong>and</strong> a bare plural) can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as def<strong>in</strong>ite without <strong>the</strong> presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> a def<strong>in</strong>ite determ<strong>in</strong>er ((11)-(13) <strong>and</strong> (20)-(22)). Second, (42) shows that a bare s<strong>in</strong>gular k<strong>in</strong>d term<br />

can be determ<strong>in</strong>erless <strong>in</strong> a post-verbal position. In (42) <strong>the</strong> bare noun dromedaire ‘dromedary’ appears<br />

<strong>in</strong> a <strong>the</strong>tic position (it is <strong>the</strong> object <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> preposition a ‘to’).<br />

(42) Chamel ressamble a dromedaire<br />

camel resemble.PRES.3SG to dromedary<br />

Il sont auques tout d’un affaire, De condicion, de nature.<br />

<strong>the</strong>y be.PRES.3PL always all <strong>of</strong>-a k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> nature<br />

‘[The] camel resembles [<strong>the</strong>] dromedary. They are always <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same k<strong>in</strong>d, with regard to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

condition <strong>and</strong> teir nature.’ (Bestiaire Marial, from <strong>the</strong> Rosarius, 14 th century, XIII Chameau,<br />

book II, chapter XLVI, 266)<br />

The only way to save <strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple as envisaged by Chierchia <strong>and</strong> his followers is to correlate<br />

<strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> to different functions, one <strong>of</strong> which be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> referential function, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> expressiveness function. If <strong>the</strong>se generalizations turn out to be solid <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> long run, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> will not automatically apply if available <strong>in</strong> a given language. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, competition between<br />

various forms to match particular mean<strong>in</strong>gs will happen at a local level, i.e. it will depend on <strong>the</strong><br />

context/on <strong>the</strong> construction. In this tradition, Grønn (2005) argues that like weak bidirectionality<br />

Blutner (1998, 2000) seems to be what is needed. ‘This version <strong>of</strong> Optimality Theory allows for partial<br />

block<strong>in</strong>g, where <strong>the</strong> unmarked form (<strong>the</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gular) “survives” <strong>and</strong> is accorded its own unmarked<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g. However, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gular competes with different marked forms <strong>in</strong> different contexts,<br />

<strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> “unmarked mean<strong>in</strong>gs” assigned to <strong>the</strong> bare s<strong>in</strong>gular may become ra<strong>the</strong>r large <strong>and</strong><br />

heteroclite.’<br />

Before <strong>the</strong> present section to a close, I would like to add one f<strong>in</strong>al set <strong>of</strong> facts from Old French<br />

that suggest <strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple regardless <strong>of</strong> how hard we try to save it is never<strong>the</strong>less confronted<br />

with optional data that are difficult to account for. It turns out that <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> a determ<strong>in</strong>er may<br />

after all be totally gratuitious from <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> syntax <strong>and</strong> semantics. In Old French, phonological, i.e.,<br />

metric, requirements can force <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> a determ<strong>in</strong>er <strong>in</strong> a particular verse. This expla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> use<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> article <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first, but not <strong>the</strong> second verse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g portion <strong>of</strong> text.<br />

(43) Il fist le ciel et le soleil<br />

he do.PAST.3SG <strong>the</strong> heaven <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> sun<br />

Et terre et mer et feu vermel<br />

<strong>and</strong> earth <strong>and</strong> sea <strong>and</strong> fire red<br />

‘He created <strong>the</strong> earth <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> sun, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> earth <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> sea <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fire all red.’<br />

(Partonopeu de Blois, c. 1182-85,1553-1554)<br />

What (43) shows is that it does not matter semantically whe<strong>the</strong>r or not an article is used. This fact<br />

shows that <strong>the</strong> Block<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple ultimately breaks down at <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Phonological Form.<br />

4. Analysis: everyth<strong>in</strong>g starts with an <br />

In Old French, a bare noun, i.e. an NP (whe<strong>the</strong>r s<strong>in</strong>gular or plural) starts out as an element denot<strong>in</strong>g<br />

. An NP can thus refer to a k<strong>in</strong>d without <strong>the</strong> need for any fur<strong>the</strong>r projection. S<strong>in</strong>ce this NP is<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpreted as mass, it is under-specified for (morphological) number, which means that NumP does not<br />

project, giv<strong>in</strong>g us <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>in</strong> (44). If we follow Chierchia, k<strong>in</strong>d terms are like mass <strong>nouns</strong>, i.e.<br />

<strong>in</strong>herently plural, where plurality is a semantic property. Morphological number may or may not<br />

surface depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> language: k<strong>in</strong>d-denot<strong>in</strong>g NPs show no such morphology <strong>in</strong> languages like<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese while <strong>the</strong>y do <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Old French. This simply follows from <strong>the</strong> fact that one language<br />

may have a s<strong>in</strong>gular/plural contrast while ano<strong>the</strong>r might not. Crucially, however, a language with a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gular/plural contrast can have bare nom<strong>in</strong>als (plurals <strong>and</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gulars) denot<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>ds.<br />

(44) NP <br />

|<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N<br />

8

This structure accounts for examples such as those <strong>in</strong> (15) <strong>and</strong> (16). For all o<strong>the</strong>r cases, NumP<br />

projects spell<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong> configuration <strong>in</strong> (45). Num is associated with un<strong>in</strong>terpretable φ-features <strong>and</strong><br />

an Agree relation is established with <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretable φ-features <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al. Semantically, NumP<br />

denotes a property. The role <strong>of</strong> NumP is to retrieve <strong>in</strong>stantiations <strong>of</strong> a k<strong>in</strong>d (objects or sub-k<strong>in</strong>ds). The<br />

nom<strong>in</strong>al carries a set <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretable φ-features that enter <strong>in</strong>to an Agree relation with <strong>the</strong><br />

un<strong>in</strong>terpretable φ-features associated with Num. Note that absence <strong>of</strong> NumP does not correlate with<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gularity: for both plural <strong>and</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gular terms, it is <strong>the</strong> case that NumP projects.<br />

(45) NumP <br />

Nums<strong>in</strong>g/pl NP <br />

u[φ] |<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N<br />

i[φ]<br />

Agree<br />

This accounts for examples such as (11) <strong>and</strong> (21). If <strong>the</strong> sentence is habitual as <strong>in</strong> (46), <strong>the</strong> habitual<br />

aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sentence is <strong>in</strong>terpreted as <strong>the</strong> modal operator Gn toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> accommodation <strong>of</strong> a<br />

contextual variable C. Here aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> property quantified on is <strong>the</strong> property <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

k<strong>in</strong>d which is number-neutral.<br />

(46) chien aiment plus home que beste dou monde generaument<br />

dog.PL love. more man.PL than animal <strong>of</strong> world generally<br />

‘Dogs like man more than any o<strong>the</strong>r animal.’<br />

(Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, CLXXXVI, Des chiens, p. 234-235)<br />

When <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al is <strong>in</strong>terpreted existentially, as <strong>in</strong> (23), I assume this is achieved via Chierchia’s<br />

(1998) Derived K<strong>in</strong>d Predication rule, which is basically <strong>the</strong> only source <strong>of</strong> existential quantification <strong>in</strong><br />

bare <strong>nouns</strong>.<br />

When <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a predicate as <strong>in</strong> (30), NumP is projected <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> predicate takes a NumP<br />

directly. No PredP need be projected as <strong>in</strong> Baker (2003). When a determ<strong>in</strong>er is projected, I assume that<br />

it is for referential purposes. Along with traditional wisdom, I assume that a speaker chooses a def<strong>in</strong>ite<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>er only if he supposes that <strong>the</strong> hearer has <strong>the</strong> means to p<strong>in</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong> referent <strong>in</strong> question<br />

among all <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r referents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same category <strong>in</strong> a given situation (<strong>the</strong> referent is unique, familiar<br />

or identifiable). Thus, on my view, D <strong>in</strong> (47) encodes def<strong>in</strong>iteness ra<strong>the</strong>r than ‘determ<strong>in</strong>erness’.<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g Lyons (1999), I assume Dets appear <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> specifier <strong>of</strong> DP. There are languages where<br />

double determ<strong>in</strong>ation is encoded: a determ<strong>in</strong>er <strong>and</strong> an affix are possible (Danish <strong>and</strong> written Icel<strong>and</strong>ic).<br />

It is thus safe to assume that <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er sits <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> specifier <strong>of</strong> DP while <strong>the</strong> affix is on <strong>the</strong> head D 0 .<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce Old French does not have affixal <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> <strong>the</strong> head D 0 rema<strong>in</strong>s empty.<br />

(47) DP<br />

Det D'<br />

D NumP <br />

Nums<strong>in</strong>g/pl NP <br />

u[φ] |<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N<br />

i[φ]<br />

Agree<br />

9<br />

As for <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>, I assume that <strong>the</strong>y project CardP (see Lyons 1999). The <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite<br />

articles un ‘a’ <strong>and</strong> uns ‘some’ clearly derive from <strong>the</strong> card<strong>in</strong>al un. They are not <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>, but ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

‘<strong>in</strong><strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong>’ (as <strong>in</strong> traditional grammars).<br />

(48) CardP<br />

un Card'<br />

Card NumP <br />

Nums<strong>in</strong>g/pl NP <br />

u[φ] |<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N<br />

i[φ]<br />

Agree<br />

The second dimension that <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> embody <strong>in</strong> Old French, as we have seen, is <strong>the</strong>ir capacity <strong>of</strong><br />

encod<strong>in</strong>g focus. When <strong>the</strong> speaker wants to <strong>in</strong>sist on a particular nom<strong>in</strong>al, he/she adds an article. This is<br />

especially relevant <strong>in</strong> object positions, s<strong>in</strong>ce it is not a focus position <strong>in</strong> Old French. When an NP is <strong>in</strong><br />

an object position <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> speaker wants to emphasize that NP, <strong>the</strong>n a determ<strong>in</strong>er is added to <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise bare noun. For those cases, I assume that a Focus phrase is needed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al doma<strong>in</strong> as<br />

represented <strong>in</strong> (49). The determ<strong>in</strong>er sits <strong>in</strong> this case <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> specifier <strong>of</strong> FocP.<br />

(49) FocusP<br />

Foc'<br />

Foc NumP <br />

Nums<strong>in</strong>g/pl NP <br />

u[φ] |<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N<br />

i[φ]<br />

Agree<br />

So far, <strong>the</strong> mechanics laid out above for Old French appear to translate quite naturally to<br />

Modern French. This is a problem s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> contrast to Old French, Modern French does not tolerate<br />

bare <strong>nouns</strong>, as can be seen from <strong>the</strong> examples <strong>in</strong> (50). Therefore, we must account for why a language<br />

A, or a previous stage <strong>of</strong> a language A, can have bare <strong>nouns</strong> while a language B, or a previous version<br />

<strong>of</strong> language B, does not.<br />

(50) a. * Chien aime chat.<br />

dog like.PRES.3SG cat<br />

‘The dog likes <strong>the</strong> cat.’<br />

b. * Hommes ont vu chiens.<br />

men be.PRES.3PL seen dogs<br />

‘Men saw dogs.’<br />

10

Thus, <strong>the</strong> one question that rema<strong>in</strong>s to be addressed before <strong>the</strong> present article draws to a close is <strong>the</strong><br />

question as to why bare <strong>nouns</strong> disappeared from <strong>the</strong> grammar <strong>of</strong> Old French <strong>and</strong> why <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong><br />

became obligatory <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> language. I would like to argue that <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite<br />

<strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> as expressors <strong>of</strong> referentiality <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> focus collapsed once plural morphology disappeared<br />

from <strong>the</strong> morphological make-up <strong>of</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>als. For object-level bare <strong>nouns</strong> to be possible at all <strong>in</strong> a<br />

given language that has a s<strong>in</strong>gular/plural contrast, number mark<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> noun is necessary. This is <strong>the</strong><br />

contention put forward <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g few pages <strong>of</strong> this article.<br />

Whereas <strong>in</strong> Old French number could appear on <strong>the</strong> noun <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er, <strong>in</strong> Modern<br />

French number appears only on <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er (‘le’ [l?] versus ‘les’ [le], ‘un’ [C] versus ‘des’ [de]). In<br />

les pommes ‘<strong>the</strong> apples’, <strong>the</strong> ‘s’ cannot be heard. The disappearance <strong>of</strong> this f<strong>in</strong>al ‘s’ as dates back from<br />

around 1300 (Fouché 1961, Joly 1995). Table 1 shows that <strong>in</strong> Old French <strong>the</strong> ‘s’ can not only mark<br />

case, but also number. As Brunot <strong>and</strong> Bruneau (1956:193) po<strong>in</strong>t out, <strong>the</strong> ‘s’ became <strong>the</strong> mark <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plural from <strong>the</strong> 13 th century onwards. This is because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disappearance <strong>of</strong> (nom<strong>in</strong>ative) case: <strong>the</strong> ‘s’<br />

has thus become <strong>the</strong> mark <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plural by accident. Importantly, <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> form on <strong>the</strong> noun had<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g: ei<strong>the</strong>r it signified plurality or obliqueness.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>gular Plural<br />

Nom<strong>in</strong>ative murs mur<br />

Oblique mur murs<br />

Table 1<br />

In fact, <strong>in</strong> Old French <strong>the</strong> morphology necessary to dist<strong>in</strong>guish beween s<strong>in</strong>gularity <strong>and</strong> plurality could<br />

appear (be heard) on <strong>the</strong> noun but not necessarily on <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>er. In <strong>the</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>ative paradigm, li<br />

could mean ei<strong>the</strong>r ‘<strong>the</strong>s<strong>in</strong>gular’ or ‘<strong>the</strong>plural’ as exemplified by <strong>the</strong> examples <strong>in</strong> (51). The only way to tell<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> noun was s<strong>in</strong>gular or plural <strong>in</strong> this case was through <strong>the</strong> morphology on <strong>the</strong> noun. Here <strong>the</strong><br />

added ‘s’ signifies s<strong>in</strong>gularity; a fact that led to great confusion s<strong>in</strong>ce that ‘s’ was also used to mark <strong>the</strong><br />

plural <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> accusative paradigm. This might expla<strong>in</strong> why f<strong>in</strong>al consonants on <strong>nouns</strong> disappeared <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

first place <strong>and</strong> why li disappeared as a determ<strong>in</strong>er, s<strong>in</strong>ce it was (now totally) ambiguous.<br />

(51) a. li chevaliers ‘<strong>the</strong> knight’<br />

b. li chevalier ‘<strong>the</strong> knights’<br />

In sum, <strong>the</strong> obligatory presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> with nom<strong>in</strong>als <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> French language is due to <strong>the</strong><br />

collapse <strong>of</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gular/plural mark<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> noun. Formally, I want to argue that this correlates with N as<br />

no longer be<strong>in</strong>g associated with φ-features. However, <strong>the</strong> question that immediately arises is how <strong>the</strong><br />

un<strong>in</strong>terpretable φ-features <strong>of</strong> Num are satisfied. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y are un<strong>in</strong>terpretable, <strong>the</strong>y cannot survive at<br />

LF. I argue that <strong>the</strong> search space <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> φ-features on Num starts with <strong>the</strong> complement <strong>of</strong> Num, but<br />

because <strong>the</strong>re is no match <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> complement, it grows to <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> specifier <strong>of</strong> Num (for <strong>the</strong> idea that<br />

Agree is cyclic, see Rezac 2003). This means that <strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ers</strong> <strong>and</strong> card<strong>in</strong>als are not merged <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

respective specifiers, ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> Modern French <strong>the</strong>y are raised <strong>the</strong>re (we thus have a change from Merge<br />

to Move + Merge <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sense <strong>of</strong> Roberts <strong>and</strong> Roussou 2003). Suppose <strong>the</strong>n that <strong>the</strong>y are merged <strong>in</strong><br />

Spec-NumP, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretable features that <strong>the</strong>y carry can satisfy <strong>the</strong> un<strong>in</strong>tepretable features <strong>of</strong> Num<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> derivation converges.<br />

(52) a. NumP ⇒ b. DP<br />

Nums<strong>in</strong>g/pl NP D'<br />

u[φ] |<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N D NumP <br />

11<br />

Det Num'<br />

i[φ]<br />

Nums<strong>in</strong>g/pl NP <br />

u[φ] |<br />

N'<br />

|<br />

N<br />

Texts used/cited<br />

La Prise d’Orange, end <strong>of</strong> 12th century, Charroi de Nîmes, 12th century, Le Chevalier à la Charrette,<br />

year c. 1180, Lai de Narcisse, year 1170, Li livres dou tresor, year 1260-1267, La vie de Sa<strong>in</strong>t Alexis,<br />

year1050, Alex v. 39-40, Aucass<strong>in</strong> et Nicolette, early 13th century, Guillaume, 12 th century, L’âtre<br />

périlleux, roman de la Table Ronde, year 1268, La Chanson de Roll<strong>and</strong>, year 1080.<br />

Enéas, year 1150, Yva<strong>in</strong>, Le Chevalier au Lion, year 1179, La Cantilene de Sa<strong>in</strong>te Eulalie, year 878,<br />

Eracle, year 1180, La Conquête de Constant<strong>in</strong>ople, c. 1212, Bestiaire Marial, from <strong>the</strong> Rosarius, 14 th<br />

century, Partonopeu de Blois, c. 1182-85.<br />

Selected references<br />

Atle, Grønn. 2005. Norwegian bare s<strong>in</strong>gulars: A note on types <strong>and</strong> sorts. Ms. <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Oslo.<br />

Baker, Mark C. 2003. Lexical categories. Verbs, <strong>nouns</strong>, <strong>and</strong> adjectives. Cambridge: Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Blutner, Re<strong>in</strong>hard. 1998. Lexical pragmatics. Journal <strong>of</strong> Semantics 15:115-162.<br />

Blutner, Re<strong>in</strong>hard. 2000. Some Aspects <strong>of</strong> Optimality <strong>in</strong> Natural Language Interpretation. Journal <strong>of</strong> Semantics 17:189-216.<br />

Bor<strong>the</strong>n, Kaja. 2003. Norwegian <strong>Bare</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gulars. PhD dissertation, Norwegian <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Science <strong>and</strong> Technology.<br />

Bouchard, Denis. 2003. Les SN sans déterm<strong>in</strong>ant en français et en anglais. In Essais sur la grammaire comparée du<br />

français et de l’anglais, eds. Miller, Philip, <strong>and</strong> Anne Zribi-Hertz, 55-95. Sa<strong>in</strong>t-Denis: Presses Universitaires de<br />

V<strong>in</strong>cenne.<br />

Bouchard, Denis. 1998. The distribution <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> adjectives <strong>in</strong> French: A consequence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bare</strong> Phrase Structure.<br />

Probus 10:139-183.<br />

Bouchard, Denis. 2002. Adjectives, number <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terfaces: Why languages vary. Oxford: Elsevier Science.<br />

Brunot, Ferd<strong>in</strong><strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Charles Bruneau. 1956. Précis de grammaire historique de la langue française. Paris: Masson.<br />

Carlier, Anne, <strong>and</strong> Michèle Goyens. 1998. De l'ancien français au français moderne: régression du degré zéro de la<br />

déterm<strong>in</strong>ation et restructuration du système des articles. Cahiers de l'Institut L<strong>in</strong>guistique de Louva<strong>in</strong> 24:77-112.<br />

Carlson, Gregory. 1977. Reference to k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>in</strong> English. PhD dissertation, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Massachusetts.<br />

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen, <strong>and</strong> R<strong>in</strong>t Sybesma. 1999. <strong>Bare</strong> <strong>and</strong> not-so-bare <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> NP. L<strong>in</strong>guistic Inquiry<br />

30:509-542.<br />

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to k<strong>in</strong>ds across languages. Natural Language Semantics 6:339-405.<br />

C<strong>in</strong>que, Giuglielmo. 1994. On <strong>the</strong> evidence for partial N movement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Romance DP. In Paths towards Universal<br />

Grammar: Studies <strong>in</strong> honor <strong>of</strong> Richard S. Kayne, eds. C<strong>in</strong>que, Giuglielmo, et al, 85-110. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C.:<br />

Georgetown <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Dayal, Veneeta. 2004. Number mark<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> (<strong>in</strong>)def<strong>in</strong>iteness <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d terms. L<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>and</strong> Philosophy 27:393-450.<br />

Defiltto, Denis. 2002. Genericity <strong>in</strong> language. Issues <strong>of</strong> syntax, logical form <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation. Aless<strong>and</strong>ria: Dell’Orso.<br />

Delfitto, Denis, <strong>and</strong> Jan Schroten. 1991. <strong>Bare</strong> plurals <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> number affix <strong>in</strong> DP. Probus 3:155-185.<br />

Déprez, Viviane. 2005. Morphological number, semantic number <strong>and</strong> bare <strong>nouns</strong>. L<strong>in</strong>gua 115:857-883.<br />

Epste<strong>in</strong>, Richard. 1995. L’article déf<strong>in</strong>i en ancien français: L’expression de la subjectivité. Langue Française 107:58-71.<br />

Epste<strong>in</strong>, Richard. 1994. The development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ite article <strong>in</strong> French. In Current issues <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>the</strong>ory, 109.<br />

Perspectives on grammaricalization, ed. Pagl<strong>in</strong>ca, William, 63-80. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjam<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

Epste<strong>in</strong>, Richard. 1993. The def<strong>in</strong>ite article: Early stages <strong>of</strong> development. In Historical L<strong>in</strong>guistics 1991, ed. Van Marle,<br />

Jaap, 111-134. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Johns Benjam<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

Esp<strong>in</strong>al, M. Teresa. 2004. Lexicalization <strong>of</strong> light verb structures <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> semantics <strong>of</strong> <strong>nouns</strong>. Catalan Journal <strong>of</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics<br />

3:15-43.<br />

Farkas, Donka, <strong>and</strong> Henriëtte de Swart. 2003. The semantics <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporation: From argument structure to discourse<br />

transparency. Stanford: CSLI Publications.<br />

Fouché, Pierre. 1961. Phonétique historique du français. Paris: Kl<strong>in</strong>cksieck.<br />

Foulet, Lucien. 1928. Petite syntaxe de l'ancien français. Paris: Éditions Champion.<br />

Fournier, Nathalie. 2002. Grammaire du français classique. Paris: Éditions Bél<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Joly, Geneviève. 1995. Précis historique du français. Paris: Arm<strong>and</strong> Col<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Knittel, Marie-Laurence. 2005. Some remarks on adjective placement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> French NP. Probus 185-226.<br />

Krifka, Manfred. 2003. <strong>Bare</strong> NPs: K<strong>in</strong>d-referr<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ites, both or nei<strong>the</strong>r? Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> SALT .<br />

Krifka, Manfred, et al. 1995. Genericity: An <strong>in</strong>troduction. In The Generic Book, eds. Carlson, Gregory, <strong>and</strong> Francis<br />

Pelletier, 1-124. Chicago: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press.<br />

Laenzl<strong>in</strong>ger, Christopher. 2005. French adjective order<strong>in</strong>g: perspectives on DP-<strong>in</strong>ternal movement types. L<strong>in</strong>gua 115:645-<br />

689.<br />

Lamarche, Jacques. 1991. Problems for N 0 -movement to Num-P. Probus 3:215-236.<br />

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 2000. The structure <strong>of</strong> DPs: some pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, parameters, <strong>and</strong> problems. In The h<strong>and</strong>book <strong>of</strong><br />

contemporary syntactic <strong>the</strong>ory, eds. Balt<strong>in</strong>, Mark, <strong>and</strong> Chris Coll<strong>in</strong>s, 562-603. Oxford: Blackwell.<br />

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 1994. Reference <strong>and</strong> proper names. L<strong>in</strong>guistic Inquiry 25:609-665.<br />

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 2001. How comparative is semantics? A unified parametric <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> bare <strong>nouns</strong> <strong>and</strong> proper names.<br />

Natural Language Semantics 9:335-369.<br />

Lyons, Christopher. 1999. Def<strong>in</strong>iteness. Cambridge: Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Mathieu, Eric. 2006a. Quirky subjects <strong>in</strong> Old French. Studia L<strong>in</strong>guistica 60:282-312.<br />

Mathieu, Eric. 2006b. Stylistic Front<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Old French. Probus 18: 219-266.<br />

Mathieu, Eric. 2006c. On <strong>the</strong> Germanic properties <strong>of</strong> Old French. Ms.<br />

Mathieu, Eric, <strong>and</strong> Ioanna Sitaridou. 2005. Split WH constructions <strong>in</strong> Classical <strong>and</strong> Modern Greek: A diachronic<br />

perspective. In Grammaticalization <strong>and</strong> parametric change, eds. Batllori, Montserrat, <strong>and</strong> Francesc Roca, 236-250.<br />

Oxford: Oxford <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Moignet, Gérard. 1973. Grammaire de l'ancien français. Morphologie - syntaxe. Paris: Kl<strong>in</strong>cksieck.<br />

Raynaud de Lage, Guy. 1983. Manuel pratique d'ancien français. Paris: Picard.<br />

Rezac, Milan. 2003. The f<strong>in</strong>e structure <strong>of</strong> cyclic Agree. Syntax 6:156-182.<br />

Roberts, Ian <strong>and</strong> Roussou, Anna. 2003. Syntactic change: A M<strong>in</strong>imalist approach to grammaticalisation. Cambridge:<br />

Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Stowell, Tim. 1989. Subjects, specifiers <strong>and</strong> X-bar <strong>the</strong>ory. In Alternative conceptions <strong>of</strong> phrase structure, eds. Balt<strong>in</strong>, Mark,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Anthony Kroch, 232-262. Chicago: Chicago <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Van Geenhoven, Veerle. 1998. Semantic <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite descriptions: Semantic <strong>and</strong> syntactic aspects <strong>of</strong> noun<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>in</strong> West Greenl<strong>and</strong>ic. Stanford: CSLI Publications.<br />

12