The Bronze Age: Mesopotamia and Iran

The Bronze Age: Mesopotamia and Iran

The Bronze Age: Mesopotamia and Iran

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

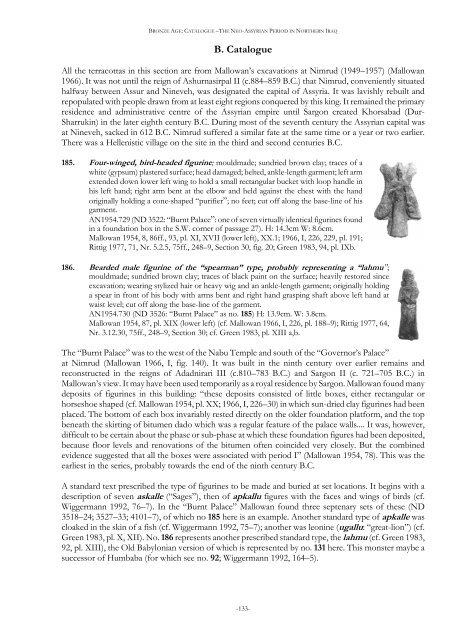

BRONZE AGE: CATALOGUE –THE NEO-ASSYRIAN PERIOD IN NORTHERN IRAQ<br />

B. Catalogue<br />

All the terracottas in this section are from Mallowan’s excavations at Nimrud (1949–1957) (Mallowan<br />

1966). It was not until the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (c.884–859 B.C.) that Nimrud, conveniently situated<br />

halfway between Assur <strong>and</strong> Nineveh, was designated the capital of Assyria. It was lavishly rebuilt <strong>and</strong><br />

repopulated with people drawn from at least eight regions conquered by this king. It remained the primary<br />

residence <strong>and</strong> administrative centre of the Assyrian empire until Sargon created Khorsabad (Dur-<br />

Sharrukin) in the later eighth century B.C. During most of the seventh century the Assyrian capital was<br />

at Nineveh, sacked in 612 B.C. Nimrud suffered a similar fate at the same time or a year or two earlier.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was a Hellenistic village on the site in the third <strong>and</strong> second centuries B.C.<br />

185. Four-winged, bird-headed figurine; mouldmade; sundried brown clay; traces of a<br />

white (gypsum) plastered surface; head damaged; belted, ankle-length garment; left arm<br />

extended down lower left wing to hold a small rectangular bucket with loop h<strong>and</strong>le in<br />

his left h<strong>and</strong>; right arm bent at the elbow <strong>and</strong> held against the chest with the h<strong>and</strong><br />

originally holding a cone-shaped “purifier”; no feet; cut off along the base-line of his<br />

garment.<br />

AN1954.729 (ND 3522: “Burnt Palace”: one of seven virtually identical figurines found<br />

in a foundation box in the S.W. corner of passage 27). H: 14.3cm W: 8.6cm.<br />

Mallowan 1954, 8, 86ff., 93, pl. XI, XVII (lower left), XX.1; 1966, I, 226, 229, pl. 191;<br />

Rittig 1977, 71, Nr. 5.2.5, 75ff., 248–9, Section 30, fig. 20; Green 1983, 94, pl. IXb.<br />

186. Bearded male figurine of the “spearman” type, probably representing a “lahmu”;<br />

mouldmade; sundried brown clay; traces of black paint on the surface; heavily restored since<br />

excavation; wearing stylized hair or heavy wig <strong>and</strong> an ankle-length garment; originally holding<br />

a spear in front of his body with arms bent <strong>and</strong> right h<strong>and</strong> grasping shaft above left h<strong>and</strong> at<br />

waist level; cut off along the base-line of the garment.<br />

AN1954.730 (ND 3526: “Burnt Palace” as no. 185) H: 13.9cm. W: 3.8cm.<br />

Mallowan 1954, 87, pl. XIX (lower left) (cf. Mallowan 1966, I, 226, pl. 188–9); Rittig 1977, 64,<br />

Nr. 3.12.30, 75ff., 248–9, Section 30; cf. Green 1983, pl. XIII a,b.<br />

<strong>The</strong> “Burnt Palace” was to the west of the Nabu Temple <strong>and</strong> south of the “Governor’s Palace”<br />

at Nimrud (Mallowan 1966, I, fig. 140). It was built in the ninth century over earlier remains <strong>and</strong><br />

reconstructed in the reigns of Adadnirari III (c.810–783 B.C.) <strong>and</strong> Sargon II (c. 721–705 B.C.) in<br />

Mallowan’s view. It may have been used temporarily as a royal residence by Sargon. Mallowan found many<br />

deposits of figurines in this building: “these deposits consisted of little boxes, either rectangular or<br />

horseshoe shaped (cf. Mallowan 1954, pl. XX; 1966, I, 226–30) in which sun-dried clay figurines had been<br />

placed. <strong>The</strong> bottom of each box invariably rested directly on the older foundation platform, <strong>and</strong> the top<br />

beneath the skirting of bitumen dado which was a regular feature of the palace walls.... It was, however,<br />

difficult to be certain about the phase or sub-phase at which these foundation figures had been deposited,<br />

because floor levels <strong>and</strong> renovations of the bitumen often coincided very closely. But the combined<br />

evidence suggested that all the boxes were associated with period I” (Mallowan 1954, 78). This was the<br />

earliest in the series, probably towards the end of the ninth century B.C.<br />

A st<strong>and</strong>ard text prescribed the type of figurines to be made <strong>and</strong> buried at set locations. It begins with a<br />

description of seven askalle (“Sages”), then of apkallu figures with the faces <strong>and</strong> wings of birds (cf.<br />

Wiggermann 1992, 76–7). In the “Burnt Palace” Mallowan found three septenary sets of these (ND<br />

3518–24; 3527–33; 4101–7), of which no 185 here is an example. Another st<strong>and</strong>ard type of apkalle was<br />

cloaked in the skin of a fish (cf. Wiggermann 1992, 75–7); another was leonine (ugallu: “great-lion”) (cf.<br />

Green 1983, pl. X, XII). No. 186 represents another prescribed st<strong>and</strong>ard type, the lahmu (cf. Green 1983,<br />

92, pl. XIII), the Old Babylonian version of which is represented by no. 131 here. This monster maybe a<br />

successor of Humbaba (for which see no. 92; Wiggermann 1992, 164–5).<br />

-133-