cuentos de barro - DSpace Universidad Don Bosco

cuentos de barro - DSpace Universidad Don Bosco

cuentos de barro - DSpace Universidad Don Bosco

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

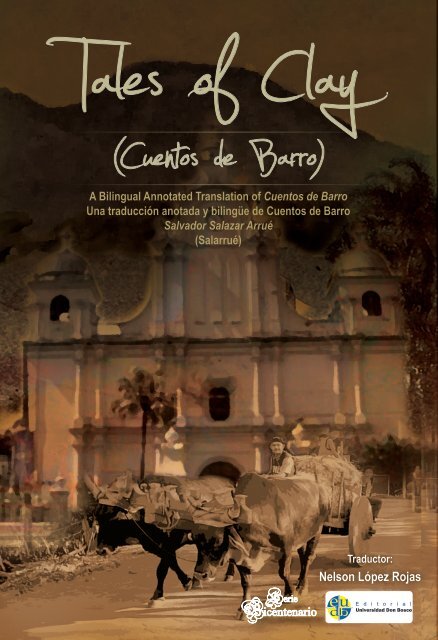

Tales of Clay (Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro)<br />

A Bilingual Annotated Translation of Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro<br />

Una traducción anotada y bilingüe <strong>de</strong> Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro<br />

Salvador Salazar Arrué<br />

(Salarrué)<br />

Traductor:<br />

Nelson López Rojas

C<br />

Editorial <strong>Universidad</strong> <strong>Don</strong> <strong>Bosco</strong>, 2011<br />

Colección Investigación<br />

Serie Bicentenario<br />

Autor: Salvador Salazar Arrué<br />

C Traductor: Nelson López Rojas<br />

Con autorización <strong>de</strong> la familia <strong>de</strong> Salvador<br />

Salazar Arrué<br />

Diseño: Melissa Beatriz Mén<strong>de</strong>z Moreno<br />

Apartado Postal 1874, San Salvador, El<br />

Salvador<br />

The heirs of Salarrué have graciously given<br />

the permission for this book to be published<br />

at EUDB.<br />

Translation of CdB into English is copyrighted<br />

by the translator.<br />

Hecho el <strong>de</strong>pósito que marca la ley<br />

Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial <strong>de</strong><br />

esta obra, por cualquier medio, electrónico o<br />

mecánico sin la autorización <strong>de</strong> la Editorial<br />

ISBN 978 99923 50 36 2

La literatura no es inocente; la traducción tampoco.<br />

Literature is not innocent. Neither is translation.<br />

(Coates, 1996:215)

Preface<br />

Ín d i c e/co n t e n t s<br />

Agra<strong>de</strong>cimientos/Acknowledgements<br />

Introducción/Introduction<br />

I. Una palabra <strong>de</strong>l traductor<br />

I. A Word from the Translator<br />

II. De cómo nace y se hace un traductor<br />

II. The Making of a Translator<br />

Prólogo por Rafael Lara-Martínez<br />

Cuentos-Tales<br />

Tranquera-Cattle Gate<br />

La botija-The Botija<br />

La honra-The Honor<br />

Semos malos-We’re Evil<br />

La casa embrujada-The Haunted House<br />

De pesca-Gone Fishin’<br />

Bajo la luna-Un<strong>de</strong>r the Moon<br />

El sacristán-The Sacristan<br />

La brusquita-She Ain’t No Floozy<br />

Noche buena-Christmas Eve<br />

Bruma-Mist<br />

Esencia <strong>de</strong> “azar”-Orange Blossom Essence<br />

En la línea-On the Train Tracks<br />

El contagio-The Apple doesn’t Fall Far from the Tree<br />

El entierro-The Burial<br />

z<br />

1<br />

3<br />

5<br />

5<br />

5<br />

7<br />

7<br />

11<br />

17<br />

17<br />

19<br />

26<br />

32l<br />

38<br />

43<br />

50<br />

55<br />

60<br />

65<br />

70<br />

74<br />

78<br />

81<br />

89

Hasta el cacho-All the Way<br />

La petaca-The Hump<br />

La Ziguanaba-La Siguanaba<br />

Virgen <strong>de</strong> Ludres-The Virgin of Lour<strong>de</strong>s<br />

Serrín <strong>de</strong> cedro-Cedar Sawdust<br />

El viento-The Wind<br />

La estrellemar-Starfish<br />

La brasa-The Ember<br />

El padre-The Priest<br />

La repunta-The Flash Flood<br />

El circo-The Circus<br />

La respuesta-The Answer<br />

La chichera-The Moonshine Factory<br />

El maishtro- The Teacher<br />

De caza- Gone Hunting<br />

La tinaja-The Earthenware Jar<br />

El mistiricuco-The Mistiricuco<br />

El brujo-The Sorcerer<br />

El negro-The Black Man<br />

Referencias/References<br />

94<br />

102<br />

108<br />

112<br />

114<br />

118<br />

121<br />

126<br />

128<br />

133<br />

137<br />

143<br />

147<br />

154<br />

159<br />

163<br />

166<br />

171<br />

178<br />

183

PrefacIo<br />

Andrés Bello consi<strong>de</strong>raba que el uso<br />

<strong>de</strong>l “vos” era abominable. Y durante<br />

décadas, y <strong>de</strong>bido a que Salarrué eligió<br />

la lengua vernácula para contar sus<br />

<strong>cuentos</strong>, los Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro también<br />

han sido etiquetados por los mismos<br />

salvadoreños como literatura <strong>de</strong><br />

inferior calidad, a diferencia <strong>de</strong> otros<br />

libros que se consi<strong>de</strong>ran como español<br />

“correcto”. En Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> se fun<strong>de</strong><br />

lo universal con lo local, lo religioso<br />

con lo mítico, lo urbano con lo rural,<br />

y la lengua vernácula con el lenguaje<br />

ordinario ... y Salarrué eligió la “lengua<br />

<strong>de</strong>l pueblo” para transmitir sus historias<br />

porque conocía a su pueblo. Salarrué<br />

nació en el oeste <strong>de</strong> El Salvador, lugar <strong>de</strong>l<br />

último “bastión indígena” <strong>de</strong> los pipiles<br />

en el país, y fue también el lugar <strong>de</strong> la<br />

masacre que los erradicara en 1932.<br />

Salarrué creció ro<strong>de</strong>ado <strong>de</strong> las culturas<br />

y lenguas <strong>de</strong> los grupos indígenas,<br />

así como <strong>de</strong> la lengua hablada por<br />

su familia. De tal manera, el lector<br />

<strong>de</strong> Salarrué como literatura popular<br />

<strong>de</strong>be superar la creencia <strong>de</strong> que leer<br />

Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> es leer sobre aquellos<br />

(un distante aquellos) sin educación,<br />

y aceptar nuestra herencia ancestral<br />

indígena que todos compartimos.<br />

Esta traducción es parte <strong>de</strong> mi tesis <strong>de</strong><br />

doctorado <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> <strong>de</strong> Nueva<br />

York en Binghamton. Las restantes<br />

cuatro partes verán la luz más a<strong>de</strong>lante<br />

en esta serie <strong>de</strong> la Editorial <strong>Universidad</strong><br />

<strong>Don</strong> <strong>Bosco</strong>.<br />

1<br />

Preface<br />

If Andrés Bello consi<strong>de</strong>red the use of<br />

the pronoun “vos” abominable, for<br />

<strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s, and because Salarrué chose<br />

the vernacular to tell these tales,<br />

Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro was also regar<strong>de</strong>d as<br />

substandard literature by its own people,<br />

as opposed to the books that uphold<br />

“proper” Spanish. In Tales of Clay he<br />

merges the universal with the local, the<br />

religious with the mythical, the urban<br />

with the rural, and the vernacular with<br />

the ordinary language... and Salarrué<br />

chose the “language of the people” to<br />

convey his stories because he knew<br />

them. Salarrué was born in Western El<br />

Salvador, which was the last “indigenous<br />

reservation” of the Pipil people in the<br />

country, and it was also the location of<br />

the Massacre that eradicated them in<br />

1932. Salarrué grew up surroun<strong>de</strong>d by<br />

the indigenous cultures and languages<br />

of the native groups as well as the<br />

“educated” language spoken by his<br />

family. Thus, the rea<strong>de</strong>r of Salarrué as<br />

popular literature must now overcome<br />

the belief that reading Tales of Clay is<br />

reading about those (a distant those)<br />

without education, and embrace<br />

our indigenous ancestry that we all<br />

share. This translation is part of my<br />

doctoral dissertation from Binghamton<br />

University. The remaining four parts<br />

will see the light later on in this series<br />

of Editorial <strong>Universidad</strong> <strong>Don</strong> <strong>Bosco</strong>.

Ag r A d e c i m i e n t o/Ac k n o w l e d g m e n t s s<br />

Mil gracias a todas las personas e instituciones que hicieron<br />

posible este trabajo.<br />

One person alone cannot do a work of this magnitu<strong>de</strong>. I am<br />

in<strong>de</strong>bted for my findings to my informants and contacts in<br />

different areas of knowledge. It would be impossible to list<br />

them all here... to you who contributed to this work, thank<br />

you.<br />

3

Un A p A l A b r A d e l<br />

t r A d U c t o r...<br />

I. De Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> a Tales of Clay<br />

La lengua que se usa en Cuentos <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>barro</strong> es tan amplia que no es suficiente<br />

el ser competente en un idioma para<br />

enten<strong>de</strong>rlo... o para traducirlo. Joan<br />

Corominas explica en la introducción<br />

a su famoso diccionario que su trabajo<br />

“se ha escrito para el público no<br />

especializado en lingüística, con objeto<br />

<strong>de</strong> informarle breve y claramente <strong>de</strong><br />

lo que se sabe acerca <strong>de</strong>l origen <strong>de</strong><br />

las palabras castellanas comúnmente<br />

conocidas por la gente educada.”<br />

(Corominas, 1976). Palabras comunes,<br />

palabras eruditas, términos técnicos<br />

<strong>de</strong> las partes <strong>de</strong> un barco o una iglesia,<br />

palabras indígenas, neologismos,<br />

arcaísmos, regionalismos... y el reto<br />

parecía insuperable <strong>de</strong>spués <strong>de</strong> cada<br />

vez que leía el libro <strong>de</strong> Salarrué lleno<br />

<strong>de</strong> semejante discurso subalterno,<br />

<strong>de</strong>sconocido para la gente “educada.”<br />

El reto se planteó: Derrida nos había<br />

ya advertido que la traducción era<br />

una tarea seria, mientras que Hermans<br />

nos <strong>de</strong>cía que “los traductores no sólo<br />

traducen” (1999: 96). Una vez que<br />

consulté la bibliografía disponible, me<br />

di cuenta <strong>de</strong> que este proyecto no era<br />

una simple traducción literaria, porque,<br />

como el traductor <strong>de</strong> Salarrué, tenía<br />

que transmitir no sólo las palabras y<br />

significados, sino también las diferentes<br />

capas lingüísticas que se plantean en<br />

estas historias.<br />

5<br />

A wo r d f r o m t h e<br />

tr A n s l A t o r<br />

I. From Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> to Tales of<br />

Clay The text in Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro is so<br />

comprehensive that it is not enough<br />

to be proficient in a language to<br />

un<strong>de</strong>rstand it… or to translate it. Joan<br />

Corominas explains in the introduction<br />

to his famous dictionary that his work<br />

“has been written… to inform in a<br />

concise manner what is known about<br />

the origin of Castilian words commonly<br />

known by cult people” (Corominas,<br />

1976). Common words, erudite words,<br />

technical terms for the parts of a boat or a<br />

church, indigenous words, neologisms,<br />

archaisms, regionalisms… and the<br />

challenge seemed insurmountable<br />

after each time I read Salarrué’s book<br />

filled with such subaltern speech,<br />

unknown to “cult people”.<br />

The challenge was posed: Derrida<br />

warned us that translation is a serious<br />

task, while Hermans stated that<br />

“translators never just translate” (1999:<br />

96). Once I consulted the available<br />

literature I realized that this project was<br />

not a plain literary translation, because<br />

as the translator of Salarrué I nee<strong>de</strong>d to<br />

convey not just words and meanings,<br />

but the different linguistic layers these<br />

stories pose.

La metodología <strong>de</strong> la traducción es<br />

bastante compleja. El proceso <strong>de</strong><br />

traducción ha sido compuesto por<br />

diferentes etapas <strong>de</strong> una forma un<br />

tanto circular: la lectura <strong>de</strong>l original<br />

la interpretación el análisis <strong>de</strong><br />

vocabulario relectura <strong>de</strong>l el original<br />

comparación <strong>de</strong> idiomas y<br />

comprobación <strong>de</strong> mis hipótesis con los<br />

informantes nativos interpretación<br />

(re) lectura <strong>de</strong>l original. Aunque<br />

soy un hablante nativo <strong>de</strong> español,<br />

nacido y educado en El Salvador, es<br />

un <strong>de</strong>safío el tratar <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>scifrar el<br />

vocabulario utilizado en los Cuentos <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>barro</strong>. Mis informantes nativos rurales<br />

<strong>de</strong>l país, las fotografías <strong>de</strong> los primeros<br />

años <strong>de</strong>l siglo XX, mi interacción con<br />

los pobladores <strong>de</strong> las zonas indígenas,<br />

y mis visitas a los mundos indígenas me<br />

han ayudado a revivir las <strong>de</strong>scripciones<br />

<strong>de</strong>l libro. Mi dominio <strong>de</strong>l idioma inglés<br />

me acredita para traducir una obra<br />

<strong>de</strong> esta magnitud. Sin embargo, para<br />

que sonara más como el original, he<br />

estudiado las obras y traducciones que<br />

se han ocupado <strong>de</strong> la lengua vernácula,<br />

y he confiado en mis informantes<br />

que leyeron mis traducciones y<br />

corroboraron o no mis hipótesis acerca<br />

<strong>de</strong>l sentir <strong>de</strong> los <strong>cuentos</strong>. Los nombres<br />

<strong>de</strong> pájaros, árboles, barcos, <strong>de</strong>talles <strong>de</strong><br />

edificios renacentistas, y cosas por el<br />

estilo fueron otra investigación aparte.<br />

Esta traducción ha sido una cuestión<br />

mucho más compleja que reúne<br />

múltiples disciplinas en la mesa.<br />

6<br />

The translation methodology is quite<br />

complex. The translation process has<br />

been composed of different stages in a<br />

somewhat circular fashion: reading the<br />

original interpreting analysis<br />

of vocabulary reading the original<br />

comparing languages and testing<br />

my choices with native informants<br />

interpreting (re) reading the original.<br />

Although I am a native speaker of<br />

Spanish, born and educated in El<br />

Salvador, it is a challenge to try to<br />

<strong>de</strong>cipher the vocabulary used in<br />

Tales of Clay. Native rural Salvadoran<br />

informants, photographs of the early<br />

years of the twentieth century, my<br />

interaction with villagers of indigenous<br />

areas, and my visits to the indigenous<br />

worlds have helped me to relive the<br />

<strong>de</strong>scriptions of the book. My command<br />

of the English language qualifies me<br />

to translate a work of this magnitu<strong>de</strong>.<br />

However, to make it sound more like<br />

the original, I have studied works and<br />

translations that have <strong>de</strong>alt with the<br />

vernacular; and I have relied on my<br />

informants who read my translations<br />

and tested my hypothesis regarding<br />

the feel of the tales. Names of birds,<br />

trees, boats, specifics of renaissance<br />

buildings, and the like have been a<br />

research by themselves.<br />

This translation has been a much<br />

more complex matter that brings<br />

multiple disciplines into play.

El alcance <strong>de</strong> mi investigación me<br />

ha llevado a muchos ámbitos: <strong>de</strong> la<br />

botánica a la arquitectura medieval, <strong>de</strong><br />

la zoología a la física, y <strong>de</strong> la agricultura<br />

a la arqueología. Al intentar llenar<br />

los vacíos <strong>de</strong> la memoria histórica,<br />

investigué usando los recursos <strong>de</strong> la<br />

historiografía, visitando los pueblos, los<br />

cementerios, los lugares mencionados<br />

en el libro, y viendo y sintiendo las<br />

<strong>de</strong>scripciones floridas <strong>de</strong> los Cuentos <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>barro</strong>. Hablé con escritores, amigos <strong>de</strong><br />

Salarrué, y con los resi<strong>de</strong>ntes locales <strong>de</strong><br />

los pueblos indígenas –más <strong>de</strong> alguno<br />

me aseguró que fue sobreviviente <strong>de</strong><br />

la masacre <strong>de</strong> 1932. El esclarecer la<br />

verdad no es una tarea fácil, y a muchos<br />

no les gusta hablar <strong>de</strong> ello. Si un país<br />

mantiene lagunas en su memoria, hay<br />

peligro que las brechas permanezcan<br />

abiertas o que se niegue la pérdida,<br />

como bien lo dijo Michel <strong>de</strong> Certeau.<br />

II. De cómo nace y se hace un<br />

traductor<br />

Ponga un letrero que diga “Pintura<br />

fresca. No tocar” y mi instinto natural<br />

es tocar con el fin <strong>de</strong> corroborar que la<br />

pintura está, <strong>de</strong> hecho, fresca. Cuando<br />

era niño me sentí atraído siempre a<br />

las cosas prohibidas. Me envenené al<br />

ingerir el jabón que quise usar para<br />

hacer burbujas, me rompí el brazo<br />

<strong>de</strong>recho, el codo y el hombro por andar<br />

en bicicleta don<strong>de</strong> las bicicletas no se<br />

<strong>de</strong>ben permitir, causé un cortocircuito<br />

en el sistema eléctrico en mi casa<br />

tratando <strong>de</strong> inventar un cautín <strong>de</strong><br />

soldadura, <strong>de</strong>scubrí la Playboy que mi<br />

tío tenía <strong>de</strong>bajo <strong>de</strong> su cama como parte<br />

<strong>de</strong> su colección académica.<br />

7<br />

The scope of my research led me to<br />

many areas: from botany to medieval<br />

architecture, from zoology to physics,<br />

and from agriculture to archeology.<br />

Seeking to fill in the gaps of historical<br />

memory, I began drawing from<br />

historiography, visiting the villages, the<br />

cemeteries, the places mentioned in the<br />

book, and seeing and feeling the florid<br />

<strong>de</strong>scriptions of Tales of Clay. I spoke<br />

with writers, friends of Salarrué, and<br />

local resi<strong>de</strong>nts of the once indigenous<br />

villages –some assured me they were<br />

survivors of the Massacre of 1932.<br />

Uncovering the truth is not an easy task<br />

and many don’t like to talk about it. If<br />

a country keeps lacunae in its memory,<br />

there is danger for the gaps to remain<br />

open or to negate the loss, as Michel <strong>de</strong><br />

Certeau puts it.<br />

II. The Making of a Translator<br />

Put a sign that says “Wet paint. Do not<br />

touch” and my natural instinct is to<br />

touch in or<strong>de</strong>r to corroborate that the<br />

paint is, in<strong>de</strong>ed, wet. As a child I was<br />

always drawn to forbid<strong>de</strong>n things. I<br />

got poisoned by swallowing the soap<br />

I inten<strong>de</strong>d to use for bubbles; I broke<br />

my right arm, elbow and shoul<strong>de</strong>r<br />

by biking where bicycles should not<br />

be allowed; I shorted out the electric<br />

system in my house by trying to invent<br />

a sol<strong>de</strong>ring gun; I discovered the<br />

journal Playboy my uncle had un<strong>de</strong>r his<br />

bed as part of his aca<strong>de</strong>mic collection.

Durante los viajes para visitar a<br />

familiares en San Miguel en el este <strong>de</strong><br />

El Salvador, me escondía para leer los<br />

libros que mi abuela tenía “guardados”<br />

en una caja fuerte, porque los libros<br />

estaban quizás por <strong>de</strong>coración, no para<br />

que un niño mocoso los leyera. En estos<br />

libros <strong>de</strong>scubrí <strong>cuentos</strong> mágicos <strong>de</strong> los<br />

dragones y reyes en países lejanos... las<br />

mismas historias que iba a encontrar<br />

más tar<strong>de</strong> en la casa <strong>de</strong> don Francisco.<br />

<strong>Don</strong> Francisco era un abogado para<br />

quien trabajé en mi juventud. Había<br />

un estudio-habitación llena <strong>de</strong> libros.<br />

Derecho, biología, física, <strong>Don</strong> Quijote y<br />

Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro. Yo era un ávido lector,<br />

a los 10 ya conocía gran<strong>de</strong>s palabras y<br />

palabras <strong>de</strong> los indios, pero un día don<br />

Francisco volvió temprano <strong>de</strong>l trabajo y<br />

me encontró en su estudio. Me advirtió<br />

que sus libros no eran para una mente<br />

como la mía. Me dijo que yo sería capaz<br />

<strong>de</strong> leer todos sus libros algún día, menos<br />

hoy. Agarró algunos <strong>de</strong> los libros que<br />

<strong>de</strong>bía leer: la gramática, el álgebra,<br />

la ortografía y la caligrafía. Años más<br />

tar<strong>de</strong>, don Francisco murió y yo nunca<br />

pu<strong>de</strong> leer el resto <strong>de</strong> sus libros.<br />

Por haber nacido en San Salvador, la<br />

capital <strong>de</strong>l país, estuve expuesto a las<br />

diferencias en la semántica, la sintaxis y<br />

la fonología. Fui testigo <strong>de</strong> los cambios<br />

en los últimos años ya que muchas <strong>de</strong><br />

las poblaciones más rurales migraban<br />

a la metrópoli en busca <strong>de</strong> una vida<br />

mejor. Mi propio vocabulario estaba<br />

cambiando con los tiempos y siempre<br />

me fascinó el vocabulario que usaba tío<br />

Luis. Era originario <strong>de</strong> San Miguel, pero<br />

se mudó a Santa Ana en el extremo<br />

opuesto <strong>de</strong>l país y, por tanto, hablaba<br />

<strong>de</strong> la variedad <strong>de</strong> español a la que había<br />

sido expuesto.<br />

8<br />

During trips to visit relatives in San<br />

Miguel in eastern El Salvador, I hid to<br />

read the books my grandmother kept<br />

“safe” in a vault because books were for<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration only, not for a snotnosed<br />

boy to read. In these books I discovered<br />

magical tales of dragons and kings in<br />

distant countries… the same stories<br />

that I would find later at <strong>Don</strong> Francisco’s<br />

house. <strong>Don</strong> Francisco was a lawyer for<br />

whom I worked in my youth. He had a<br />

study-room full of books. Law, biology,<br />

physics, <strong>Don</strong> Quijote and Cuentos <strong>de</strong><br />

Barro. I was an avid rea<strong>de</strong>r at the age of<br />

10. I knew big words and Indian words,<br />

but one day <strong>Don</strong> Francisco came back<br />

early from work and he found me in<br />

his study. He warned me that his books<br />

were not for a mind like mine. He said<br />

that I would be able to read all of his<br />

books someday, but not today, though.<br />

He grabbed some of the books that I<br />

should be reading: grammar, algebra,<br />

orthography and calligraphy. Years<br />

later, <strong>Don</strong> Francisco died and I was<br />

unable to read the rest of his books.<br />

Born in San Salvador, the capital of the<br />

country, I was exposed to differences<br />

in semantics, syntax, and phonology.<br />

I witnessed changes over the years<br />

as more and more rural populations<br />

came to the metropolis in search of<br />

a better life. My own vocabulary was<br />

changing with the times and I was<br />

always fascinated with the vocabulary<br />

Uncle Luis used. He was originally from<br />

San Miguel, but moved to Santa Ana at<br />

the opposite end of the country and,<br />

thus, he spoke the variety of Spanish to<br />

which he had been exposed.

A lo largo <strong>de</strong> mi educación primaria<br />

teníamos que leer Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong> Salarrué como parte <strong>de</strong>l canon <strong>de</strong><br />

la literatura salvadoreña en el sistema<br />

educativo ya que era el “padre” <strong>de</strong><br />

la literatura. Como éramos niños,<br />

mis compañeros y yo siempre nos<br />

burlábamos <strong>de</strong> la forma inculta en que<br />

hablaban los personajes <strong>de</strong> Salarrué.<br />

Nosotros, los habitantes supremos<br />

<strong>de</strong> la ciudad capital, rechazábamos el<br />

discurso autóctono por estar “un grado<br />

por <strong>de</strong>bajo <strong>de</strong> nosotros.” Para esta<br />

traducción, he leído y releído el libro en<br />

español y me enloquecí con la cantidad<br />

<strong>de</strong> información que no conocía y con<br />

el hecho <strong>de</strong> que la mayoría <strong>de</strong> estas<br />

palabras que son parte <strong>de</strong> nuestra<br />

habla cotidiana se había ignorado en<br />

los diccionarios y en la literatura oficial.<br />

Mi trabajo <strong>de</strong> traducir a Salarrué al<br />

inglés es importante para el estudio <strong>de</strong><br />

la evolución cultural y para <strong>de</strong>sexotizar<br />

la creencia <strong>de</strong> que uno pue<strong>de</strong> valorar<br />

nuestras raíces y sentirse indígena al<br />

visitar los sitios arqueológicos, mientras<br />

que los salvadoreños invisibilizamos<br />

a los pueblos indígenas que están<br />

frente a nosotros. Es mi anhelo que<br />

mi traducción traiga nueva luz sobre<br />

el pasado turbulento <strong>de</strong> nuestra<br />

nación, para que podamos apren<strong>de</strong>r<br />

a no cometer los mismos errores en el<br />

futuro.<br />

9<br />

Throughout my elementary education<br />

we had to read Salarrué’s Cuentos <strong>de</strong><br />

Barro as part of the canon of Salvadoran<br />

literature in the educational system<br />

since he is “the father” of Salvadoran<br />

literature. As children, my classmates<br />

and I always ma<strong>de</strong> fun of the way<br />

Salarrué’s characters spoke. We, the<br />

supreme inhabitants of the capital city,<br />

rejected the autochthonous speech<br />

for being a “<strong>de</strong>gree below us.” For this<br />

translation, I read and re-read the book<br />

in Spanish and became infatuated with<br />

the amount of information that I didn’t<br />

know, and with the fact that most of<br />

these words that are part of our daily<br />

speech had been ignored in dictionaries<br />

and in the official literature.<br />

My ren<strong>de</strong>ring of Salarrué’s work into<br />

English is significant for the study of<br />

cultural evolution and to <strong>de</strong>-exoticize<br />

the belief that one can feel indigenous<br />

by visiting the archeological sites while<br />

Salvadorans keep invisibilizing the<br />

indigenous peoples in front of them. It<br />

is my hope that my translation will shed<br />

new light on our nation’s troubled past<br />

so that we can learn to avoid making<br />

the same mistakes in the future.

pr ó l o g o<br />

De la est-ética en Salarrué: Mediación política y re<strong>de</strong>nción estética<br />

Por Rafael Lara-Martínez<br />

I. De la est-ética nacional-popular <strong>de</strong> Salarrué…<br />

Ante los <strong>de</strong>sastres <strong>de</strong> la historia siempre existe la esperanza <strong>de</strong> rescatar un asi<strong>de</strong>ro<br />

ético <strong>de</strong> sus vestigios. Desconsolada y optimista, nuestra herencia se aferra a un<br />

salvoconducto por efímero que sea. Este apoyo moral que <strong>de</strong>l pasado se proyecta<br />

hacia el presente, en El Salvador posee un nombre propio: Salarrué (1899-1975). Su<br />

vida carismática y su obra prolífica lo distinguen como un autor polifacético y una<br />

persona integral.<br />

Se inicia <strong>de</strong> místico en una sinfonía literaria y pictórica —O-Yarkandal (1929/1974)—<br />

que hipotéticamente <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong>ña el cuerpo. Se alza en viaje astral hacia un mundo<br />

imaginario sin amarres reales. En sus alturas espirituales lo real se disipa para<br />

volverse etéreo. Hasta el ojo crítico <strong>de</strong>l nicaragüense Sergio Ramírez en su clásica<br />

introducción a El ángel en el espejo (Caracas, 1976) lo imagina impalpable, sin<br />

conexión alguna con la realidad socio-política que transita a diario. Salarrué viviría<br />

en “un universo irreal” sin mancha política.<br />

No importa que la segunda edición ilustrada<br />

muestre lo obvio: dos cuerpos femeninos<br />

<strong>de</strong>snudos acariciándose. El presente nocentroamericano<br />

lo llamaría lesbianismo.<br />

Tampoco interesa que ese universo <strong>de</strong><br />

una Atlántida remota se <strong>de</strong>senvuelva<br />

en el crimen, en el asesinato ritual, en la<br />

<strong>de</strong>capitación, en la violencia. Importa<br />

rescatar cierta evi<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> un terreno<br />

fértil en el cual la izquierda contemporánea<br />

injerta una i<strong>de</strong>a <strong>de</strong> literatura sin tacha<br />

mundana durante décadas <strong>de</strong> dictadura<br />

militar. En literatura suce<strong>de</strong> lo contrario<br />

<strong>de</strong>l sentido común y <strong>de</strong>l refranero popular.<br />

Cuando “la mona se viste <strong>de</strong> seda, mona ya<br />

no se queda”. Luego, Salarrué <strong>de</strong>scien<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>l<br />

empíreo inmaculado hacia lo campesino en<br />

11

Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> (1933, ilustrados por José Mejía Vi<strong>de</strong>s) y hacia el habla infantil en<br />

Cuentos <strong>de</strong> cipotes (1945/1961). Su fecha clave <strong>de</strong> publicación —un año <strong>de</strong>spués<br />

<strong>de</strong> la matanza o etnocidio <strong>de</strong> 1932— lo hace susceptible <strong>de</strong> un rescate inigualable<br />

<strong>de</strong> lo popular. Los actores campesinos y la reproducción “fi<strong>de</strong>digna” <strong>de</strong> la oralidad<br />

lo convertirían en el candidato i<strong>de</strong>al <strong>de</strong> una contraofensiva artística que <strong>de</strong>safía<br />

toda censura <strong>de</strong>l régimen en boga, el <strong>de</strong>l general Maximiliano Hernán<strong>de</strong>z Martínez<br />

(1931-1934, 1935-1939, 1939-1944). Junto a la plástica <strong>de</strong> su ilustrador, Mejía<br />

Vi<strong>de</strong>s, el regionalismo <strong>de</strong> Salarrué se opondría a una política cultural en ciernes. Se<br />

presupone que al régimen le interesaría suprimir toda presencia indígena luego <strong>de</strong><br />

la revuelta <strong>de</strong> 1932, la cual algunos califican <strong>de</strong> vernácula y otros <strong>de</strong> comunista. La<br />

documentación primaria que <strong>de</strong>niega dicha supresión se halla siempre ausente <strong>de</strong><br />

los estudios históricos.<br />

Sea cual fuere la motivación política <strong>de</strong> la revuelta, resta <strong>de</strong>mostrar que existe una<br />

correlación, incluso indirecta, entre el rescate artístico <strong>de</strong> lo rural y el <strong>de</strong> lo indígena<br />

en Salarrué y una contraofensiva artística. Baste un recorte <strong>de</strong>l Suplemento <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Diario Oficial (1934) para verificar que el discurso liberador <strong>de</strong> la izquierda lo anticipa<br />

el régimen mismo <strong>de</strong> Martínez. La “liberación <strong>de</strong>l campesinado” la inaugura el<br />

martinato bajo la aureola <strong>de</strong> un Minimum Vital <strong>de</strong> corte masferreriano: vivienda,<br />

educación, salud, etc. En paradoja irresoluble, las reformas revolucionarias que<br />

la actualidad <strong>de</strong>l cambio le atribuye a los antecesores <strong>de</strong> su causa caracterizan al<br />

martinato mismo en su i<strong>de</strong>al indigenista.<br />

12

Igualmente, la censura editorial que la literatura <strong>de</strong> Salarrué burlaría al elevar al<br />

indígena-campesino al estatuto <strong>de</strong> héroe literario, sería una reprimenda contra sus<br />

propios colegas y amigos teósofos entre quienes se cuenta Hugo Rinker, censor<br />

oficial. No habría una frontera evi<strong>de</strong>nte entre censor y crítico. Ambos pertenecen<br />

a una misma logia teosófica y comparte un universo <strong>de</strong> creencias. Junto a Rinker,<br />

en plena campaña <strong>de</strong> reelección <strong>de</strong>l general Martínez, en 1934, Salarrué presi<strong>de</strong> un<br />

comité porque “el gran libertador <strong>de</strong> la mente humana” [Krishnamurti] “nos traiga su<br />

mensaje <strong>de</strong> luz y <strong>de</strong> verdad”. Habría un enlace inmediato, irreconocido, que ligaría<br />

lo material a lo espiritual, la teosofía a la política <strong>de</strong>l martinato.<br />

Al lector le toca juzgar si los eventos políticos <strong>de</strong> “liberación <strong>de</strong>l campesino” y <strong>de</strong><br />

“liberación <strong>de</strong>l alma humana” se correlacionan entre sí, en plena campaña política<br />

por la reelección <strong>de</strong> un colega teósofo. Sería posible que si existiera burla alguna en<br />

Salarrué a la política oficial, este engaño salpicaría sus propias creencias teosóficas<br />

que se realizan en el reino político <strong>de</strong> este mundo bajo el mandato <strong>de</strong> un colega y<br />

amigo. Pero este enlace entre la metafísica y la política resulta tema tabú hasta el<br />

presente.<br />

La obra cumbre <strong>de</strong>l simulacro campesino en Salarrué no <strong>de</strong>muestra su oposición<br />

al proyecto nacional-popular <strong>de</strong> Martínez. En cambio, <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> 1932, el autor señala<br />

su acor<strong>de</strong> parcial con el régimen. Esta anuencia la comprobaría una investigación<br />

que todos sus <strong>de</strong>fensores elu<strong>de</strong>n. Nadie rastrea la documentación primaria <strong>de</strong>l<br />

martinato y la recepción que obtienen Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> y Cuentos <strong>de</strong> cipotes en las<br />

publicaciones oficiales <strong>de</strong>l régimen.<br />

Tampoco nadie menciona que, luego <strong>de</strong> su elección en 1935, Martínez nombra a<br />

Salarrué <strong>de</strong>legado oficial a la Primera Exposición Centroamericana <strong>de</strong> Artes Plásticas,<br />

en octubre en San José, Costa Rica. El triunfo salvadoreño se <strong>de</strong>be al apoyo oficial<br />

al indigenismo artístico, es <strong>de</strong>cir, a la corriente <strong>de</strong> pensamiento que los críticos <strong>de</strong><br />

Martínez, sin documentación primaria, arguyen que su régimen acalla.<br />

13

Hay que ocultar la participación <strong>de</strong> Salarrué en el <strong>de</strong>spegue <strong>de</strong> una “política <strong>de</strong><br />

la cultura” en la Biblioteca Nacional para que su propuesta inspire a la izquierda<br />

contemporánea. Al hacer visible la sensibilidad campesina-indígena en su<br />

expresión, su estética inaugura una ética nacionalista que confun<strong>de</strong> los extremos<br />

políticos y partidarios en una sola “comunidad imaginaria”. Funciona tal cual un<br />

centro magnético que atrae los polos opuestos a una esfera neutral.<br />

En síntesis, el escondrijo historiográfico verifica cómo el proyecto cultural <strong>de</strong> la<br />

<strong>de</strong>recha y <strong>de</strong> la izquierda en curso —martinistas, comprometidos, ex-sandinista en<br />

el caso <strong>de</strong> Ramírez o la <strong>de</strong>l cambio salvadoreño actual— se apropia <strong>de</strong> un diseño<br />

artístico <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>recha. Lo <strong>de</strong>scontextualiza —abstrayendo las obras literarias y<br />

plásticas <strong>de</strong> su intención política original— y, al cabo, lo propone como mo<strong>de</strong>lo a<br />

imitar en el presente.<br />

El bosquejo cultural <strong>de</strong> la izquierda es una copia, una repetición <strong>de</strong> un simulacro<br />

artístico <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>recha. Las rigurosas exigencias revolucionarias vigentes las cumple<br />

la política cultural nacional-popular <strong>de</strong> los años treinta. No hay nada nuevo bajo el<br />

sol. Sólo existe el eterno retorno <strong>de</strong> lo mismo que, como el péndulo, se disfraza <strong>de</strong><br />

cambio.<br />

II. …a la traducción <strong>de</strong> Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong>/Tales of Clay<br />

Esta encrucijada política <strong>de</strong> Salarrué no implica que se invali<strong>de</strong> su juicio estético.<br />

Por lo contrario, al visualizar lo indígena-campesino y lo infantil popular como acto<br />

<strong>de</strong> habla y <strong>de</strong> cultura, el autor funda un proyecto <strong>de</strong> re-presentación <strong>de</strong> primera<br />

magnitud. Inaugura una nacionalidad que rompe las oposiciones partidarias hasta<br />

congeniarlas en un terreno artístico neutro. Reconcilia sus diferencias gracias a un<br />

proyecto único <strong>de</strong> nación. La re<strong>de</strong>nción estética <strong>de</strong>l indígena se extien<strong>de</strong> como<br />

territorio nacional <strong>de</strong> mediación política entre los extremos.<br />

Ningún otro artista salvadoreño es capaz <strong>de</strong> seducir a ambos polos por medio <strong>de</strong> un<br />

simulacro tal <strong>de</strong> nacionalidad. La obra salarrueriana se llamaría “el falso falsificador”.<br />

Exhibe un calco tan realista <strong>de</strong> la verdad que sus observadores ya no distinguen<br />

entre la copia y el original. Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> expone una verda<strong>de</strong>ra “Salvadoran<br />

Matrix” que suplanta lo real, incluso a ochenta años <strong>de</strong> su edición.<br />

14

Des<strong>de</strong> sus lectores originales olvidados —los artistas indigenistas que forjan la<br />

“política <strong>de</strong> la cultura” <strong>de</strong>l martinato— los diversos gobiernos militares siguientes,<br />

el elogio <strong>de</strong> la generación comprometida (Roberto Armijo y Roque Dalton),<br />

el aplauso <strong>de</strong> Ramírez y la ovación actual, el libro representa el mejor acto <strong>de</strong><br />

fundación imaginaria <strong>de</strong> la nacionalidad salvadoreña. Ni siquiera el best seller <strong>de</strong>l<br />

poeta salvadoreño más aclamado —Las historias prohibidas <strong>de</strong>l Pulgarcito (1974) <strong>de</strong><br />

Roque Dalton— congrega posiciones tan adversas a su favor. Su lectura no funda<br />

un proyecto unificado <strong>de</strong> nación, <strong>de</strong> izquierda a <strong>de</strong>recha.<br />

En este logro est-ético se inserta la propuesta <strong>de</strong> Nelson López Rojas por traducir<br />

ese libro clave al inglés. Sería la primera tentativa <strong>de</strong> proyectar hacia una arena<br />

internacional el mayor legado artístico <strong>de</strong> El Salvador. Su trabajo lingüístico es<br />

minucioso. La traducción no sólo reproduce el contenido <strong>de</strong> cada cuento. Recrea<br />

el apoyo material sobre el cual se levanta cada contenido concreto. La exigencia<br />

salarrueriana requiere que exista una consonancia absoluta entre el sonido y el<br />

sentido. El sonido no ofrece un simple asiento que recibe el dictado <strong>de</strong> un contenido<br />

el cual se vuelve sensible al expresarse. El sonido forja el sentido.<br />

Si la ética indígena-campesina sólo es visualizada por una estética, su contenido<br />

cultural es materializado una ca<strong>de</strong>na sonora, en un juego interactivo entre el<br />

sonido y el sentido. He ahí el gran obstáculo que López Rojas <strong>de</strong>be vencer. Haría<br />

que el sentido surja <strong>de</strong>l sonido. Esta cuestión es ardua. Si <strong>de</strong>cantar el español<br />

rural salvadoreño al estándar no resulta fácil, tanto más difícil resulta trasvasarlo<br />

hacia una lengua extranjera. O quizás, el castellano es ya un idioma extranjero.<br />

Quizás…<br />

Por esa exigencia, López Rojas no necesita contextualizar la obra en su marco sociopolítico.<br />

En cambio, precisa elaborar un análisis lingüístico exhaustivo <strong>de</strong> lo más<br />

diversos niveles lingüísticos en Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> y <strong>de</strong> su trasposición al inglés. A<br />

nivel fonológico, se preguntaría cuáles sonorida<strong>de</strong>s inglesas transcriben la armonía<br />

sonora, casi intraducible, <strong>de</strong> “Kusususapo vengan acá cojan al sapo que se me va”, o <strong>de</strong><br />

“cabsa que misteris cuquis cantis rompis rabis caleberis coquis, sacamalaca, trufis trofis,<br />

safety matches y siacabuche”.<br />

A la reproducción <strong>de</strong> la musicalidad le prosigue la búsqueda <strong>de</strong> un ritmo melódico<br />

que calque la morfología y la sintaxis <strong>de</strong>l español salvadoreño regional. Un ejemplo<br />

<strong>de</strong> Cuentos <strong>de</strong> cipotes basta. Para el héroe, el valor <strong>de</strong> un objeto no <strong>de</strong>riva <strong>de</strong><br />

sus cualida<strong>de</strong>s inherentes. Proce<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> los atributos que el discurso, cargado <strong>de</strong><br />

afectividad, le asigna como si se tratase <strong>de</strong> propieda<strong>de</strong>s que emanaran directamente<br />

15

<strong>de</strong>l mismo objeto. En el ejemplo siguiente se trata <strong>de</strong> un acor<strong>de</strong>ón. “Es [...] un<br />

barrigante farolero que siabre naipiado, siacurruca y se culumpia, suspira diamores,<br />

eruta sin malcria<strong>de</strong>sa, se enchuta en la invisivilidad y se <strong>de</strong>spereza gatiado.<br />

La enseñanza es simplemente radical. La recreación idiomática que se <strong>de</strong>leita en<br />

asociar sonidos y palabras inventadas muestra la importancia que posee la lengua<br />

al <strong>de</strong>terminar los objetos reales en el mundo. La poética salarruerina nos instruye<br />

hasta qué punto las palabras hacen las cosas. Engendran una aureola subjetiva<br />

sobre lo sensible. La lengua rural salvadoreña crea, fragua un mundo tan singular<br />

que sólo López Rojas se atreve por vez primera en ochenta años a trasvasarla hacia<br />

una matrix ajena.<br />

Asimismo, López Rojas <strong>de</strong>canta una estética —una esfera <strong>de</strong> la percepción y<br />

sensación humana— la cual indaga las cualida<strong>de</strong>s sensibles <strong>de</strong> las cosas. La cultura<br />

rural salvadoreña traza una serie <strong>de</strong> correspon<strong>de</strong>ncias entre mundo natural y<br />

humano. El mundo se vive por medio <strong>de</strong> los sentidos. Tanto es así que el tiempo<br />

no lo mi<strong>de</strong> el reloj. Lo mi<strong>de</strong> una dimensión sensitiva que privilegia la vista, el olfato<br />

y el oído como normas que recortan la duración. El amanecer, la tar<strong>de</strong> y la noche<br />

se observan, se huelen y se escuchan <strong>de</strong> manera propia. Basta un par <strong>de</strong> ejemplos.<br />

“La fragancia <strong>de</strong> la mañana venía mera cargada”. “La aurora se iba subiendo por la<br />

pared <strong>de</strong>l oriente, como una enreda<strong>de</strong>ra”.<br />

En este intercambio entre objetos físicos y observador rural se engendra una<br />

cultura como universo <strong>de</strong> correspon<strong>de</strong>ncias entre un macrocosmos natural que se<br />

rin<strong>de</strong> ante la cultura y un microcosmos humano que a su vez se somete al influjo<br />

<strong>de</strong> lo natural. La conversión <strong>de</strong>l mundo en cosmos se opera gracias a la actividad<br />

sensorial <strong>de</strong> un observador, quien inscribe su propia subjetividad perceptiva en el<br />

flujo <strong>de</strong>l tiempo objetivo.<br />

López Rojas enfrenta todos esos <strong>de</strong>safíos para ofrecer la primera traducción<br />

completa <strong>de</strong> Cuentos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> en una lengua extrajera. Su meticuloso quehacer<br />

<strong>de</strong> traductor e intérprete la aplaudiría El Salvador en su conjunto, ya que disemina<br />

hacia el extranjero la enciclopedia primordial que compila nuestra nacionalidad.<br />

La disemi-Nación que López Rojas inaugura hace <strong>de</strong> la comunidad imaginaria<br />

salvadoreña —compartida <strong>de</strong> izquierda a <strong>de</strong>recha— un verda<strong>de</strong>ro círculo completo<br />

<strong>de</strong> la educación política nacional. Ojalá que López Rojas ensanche este conocimiento<br />

hacia otras obras fundadoras <strong>de</strong> lo salvadoreño. Esta tarea <strong>de</strong> expansión global <strong>de</strong><br />

lo regional es su misión, su <strong>de</strong>stino hacia el futuro.<br />

16

TraNquera<br />

Como el alfarero <strong>de</strong> Ilobasco mo<strong>de</strong>la sus<br />

muñecos <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong>: sus viejos <strong>de</strong> cabeza<br />

temblona, sus jarritos, sus molen<strong>de</strong>ras,<br />

sus gallos <strong>de</strong> pitiyo, sus chivos patas <strong>de</strong><br />

clavo, sus indios cacaxteros1 y en fin,<br />

sus batidores panzudos; así, con las<br />

manos untadas <strong>de</strong> realismo; con toscas<br />

manotadas y uno que otro sobón rítmico,<br />

he mo<strong>de</strong>lado mis Cuentos <strong>de</strong> Barro.<br />

Después <strong>de</strong> la hornada, los más rebel<strong>de</strong>s<br />

salieron con pedazos un tanto crudos;<br />

uno que otro se <strong>de</strong>scantilló; éste salió<br />

medio rajado y aquél boliado dialtiro;<br />

dos o tres se hicieron chingastes.<br />

Pobrecitos mis <strong>cuentos</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong>... Nada<br />

son entre los miles <strong>de</strong> <strong>cuentos</strong> bellos que<br />

brotan día a día; por no estar hechos en<br />

torno, van <strong>de</strong>formes, toscos, viciados;<br />

porque, ¿qué saben los nervios <strong>de</strong> línea<br />

pura, <strong>de</strong> curva armónica? ¿Qué sabe el<br />

rojizo tinte <strong>de</strong> la tierra quemada <strong>de</strong> lakas<br />

y barnices?; y el palito rayador, ¿qué sabe<br />

<strong>de</strong> las habilida<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>l buril?... Pero <strong>de</strong>l<br />

<strong>barro</strong> <strong>de</strong>l alma están hechos; y don<strong>de</strong><br />

se sacó el material un hoyito queda, que<br />

cU e n t o s /tA l e s<br />

17<br />

caTTle GaTe<br />

As the potter of Ilobasco 2 sculpts his<br />

figures of clay: his old people with shaky<br />

heads, his little pitchers, his women<br />

going to the mill, his rooster-whistles,<br />

his goats crafted with legs of nails, his<br />

figures of indigenous people carrying<br />

cacaxtes 3 on their backs, and even his<br />

figures of burly men beating mixtures<br />

for cattle, for bread, for sugar mills...<br />

Just like that, with realism all over his<br />

messy hands; I have mol<strong>de</strong>d my Tales<br />

of Clay with cru<strong>de</strong> touches here, and<br />

rhythmic touches there.<br />

After the kiln, the most rebellious ones<br />

came out with some pieces rather raw.<br />

There were others that broke; this one<br />

came out a little cracked, and that one<br />

came out bad; two or three shattered<br />

into a hundred pieces.<br />

Oh my poor tales of clay... They are<br />

nothing among the thousands of<br />

beautiful tales that sprout daily. Since<br />

they were not ma<strong>de</strong> on a potter’s wheel,<br />

they go into the world <strong>de</strong>formed, coarse,<br />

marred; because, what do his nerves<br />

know about pure lines, about harmonic<br />

curves? 4 What does the reddish tint of<br />

burned clay know about lacquer and<br />

varnishes? And the little stick that<br />

makes figures, what does it know<br />

1. RAE: cacastle. (Del nahua cacaxtli, armazón). 1. m. El Salv., Guat., Hond. y Méx. Armazón <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra para<br />

llevar algo a cuestas.<br />

2. Town in Central El Salvador known for producing the best pottery in the country.<br />

3. A woo<strong>de</strong>n frame worn on someone’s back to carry goods.<br />

4. In physics, Harmonic curve or sine curve is a pictorial representation of a harmonic motion. Harmonic<br />

motion is the movement of an object that repeats its motion over and over again.

los inviernos interiores han llenado <strong>de</strong><br />

melancolía. Un vacío queda allí don<strong>de</strong><br />

arrancamos para dar, y ese vacío sangra<br />

satisfacción y buena voluntad.<br />

Allí va esa hornada <strong>de</strong> cuenteretes,<br />

medio crudos por falta <strong>de</strong> leña: el sol se<br />

encargará <strong>de</strong> irlos tostando.<br />

5. Like a chisel, the tool of an engraver.<br />

18<br />

about the skillful burin? 5 Nevertheless,<br />

these tales are ma<strong>de</strong> from the soul of<br />

the clay; and there is a little hole left<br />

where the material was extracted, and<br />

where past winters have filled them up<br />

with melancholy. A hole in the ground<br />

is left where we took away to give, and<br />

that emptiness bleeds satisfaction and<br />

a sense of goodwill.<br />

There goes this batch of tales, half<br />

raw because there was not enough<br />

firewood. The sun will finish toasting<br />

them little by little.

la BoTIJa<br />

José Pashaca era un cuerpo tirado en<br />

un cuero; el cuero era un cuero tirado<br />

en un rancho; el rancho era un rancho<br />

tirado en una la<strong>de</strong>ra.<br />

Petrona Pulunto era la nana <strong>de</strong> aquella<br />

boca:<br />

—¡Hijo: abrí los ojos; ya hasta la color<br />

<strong>de</strong> que los tenés se me olvidó!<br />

José Pashaca pujaba, y a lo mucho<br />

encogía la pata.<br />

—¿Qué quiere, mama?<br />

—¡Qués nicesario que tioficiés en algo,<br />

ya tas indio entero! 7<br />

—¡Agüén!...<br />

Algo se regeneró el holgazán: <strong>de</strong> dormir<br />

pasó a estar triste, bostezando.<br />

Un día entró Ulogio Isho con un<br />

cuenterete. Era un como sapo <strong>de</strong> piedra,<br />

que se había hallado arando. Tenía el<br />

sapo un collar <strong>de</strong> pelotitas y tres hoyos:<br />

uno en la boca y dos en los ojos.<br />

19<br />

THe BoTIJa 6<br />

José Pashaca was a body thrown into a<br />

hi<strong>de</strong>; the hi<strong>de</strong> was a hi<strong>de</strong> thrown into<br />

a shack; the shack was a shack thrown<br />

onto a hill.<br />

Petrona Pulunto was this bum’s ma:<br />

“Son, open your eyes; I’ve even<br />

forgotten what color they are!”<br />

José Pashaca moaned and the most<br />

she could get out of him was that he<br />

tucked his leg.<br />

“What ya want, Ma?”<br />

“All I’m sayin’ is that it’s time ya find<br />

somethin’ to do, Lord knows you is a<br />

grown man!” 8<br />

“Alright…!”<br />

Somehow the lazy guy regenerated 9<br />

himself: he quit sleeping, became sad,<br />

and yawned.<br />

One day Ulogio Isho entered the house<br />

carrying a dingus. 10 It resembled a<br />

stone frog that he had found when<br />

plowing. The frog had three holes: one<br />

for a mouth and two for the eyes; it also<br />

had a necklace of small beads.<br />

6. The Earthenware Jug. A botija was an instrument used to hi<strong>de</strong> or put money away. When people died,<br />

sometimes they did not tell anyone about their botijas and let them buried.<br />

7. El escritor es inconsistente para señalar el cambio vernáculo. A veces se usa cursiva, a veces no.<br />

8. “Indio entero” is literally “a grown Indian,” but the connotation of indian as the lowest class is not<br />

equivalent in English. See section on “Invisibilizing All Things Indigenous.”<br />

9. vt to restore and renew somebody morally or spiritually.<br />

10. Salvadoran Spanish: “a tale.” An object which name is either unknown or forgotten.

—¡Qué feyo este baboso! —llegó<br />

diciendo. Se carcajeaba—; ¡meramente<br />

el tuerto Can<strong>de</strong>!...<br />

Y lo <strong>de</strong>jó, para que jugaran los cipotes12 <strong>de</strong> la María Elena.<br />

Pero a los dos días llegó el anciano<br />

Bashuto, y en viendo el sapo dijo:<br />

—Estas cositas son obra <strong>de</strong>nantes, <strong>de</strong><br />

los agüelos13 <strong>de</strong> nosotros. En las aradas<br />

se incuentran catizumbadas. También<br />

se hallan botijas llenas dioro.<br />

José Pashaca se dignó arrugar el pellejo<br />

que tenía entre los ojos, allí don<strong>de</strong> los<br />

<strong>de</strong>más llevan la frente.<br />

—¿Cómo es eso, ño Bashuto?<br />

Bashuto se <strong>de</strong>sprendió <strong>de</strong>l puro, y tiró<br />

por un lado una escupida gran<strong>de</strong> como<br />

un caite15 , y así sonora.<br />

—Cuestiones <strong>de</strong> la suerte, hombre. Vos<br />

vas arando y ¡plosh!, <strong>de</strong>rrepente pegás<br />

en la huaca, y yastuvo; tihacés <strong>de</strong> plata.<br />

—¡Achís! 16 , ¿en veras, ño 17 Bashuto?<br />

20<br />

“What an ugly thing!” 11 he said as he<br />

entered the shack. He roared with<br />

laughter; “it looks just like Can<strong>de</strong>, the<br />

one-eyed pirate…!”<br />

He left it there for Maria Elena’s kids to<br />

play with.<br />

Two days later, el<strong>de</strong>rly Bashuto arrived<br />

at the house, and looking at the frog he<br />

said:<br />

“These things are ancient works, of our<br />

ancestors. There are plenty of these<br />

objects in the plowing fields. One can<br />

also find jugs filled with gold.”<br />

Finally, the not very bright José Pashaca<br />

finally ma<strong>de</strong> an effort to think, wrinkling<br />

the skin between his eyes.<br />

“What do you mean, Señor Bashuto?” 14<br />

Bashuto took the cigar out of his mouth,<br />

and he hurled a gob as big and as loud<br />

as the snap of a caite 18 sandal.<br />

“It’s a matter of luck, man. You’re<br />

plowing and plosh! All of a sud<strong>de</strong>n you<br />

hit the jug, and that’s it, you’re rich<br />

“Holy cow! Is that so, Señor Bashuto?”<br />

11. “Baboso” conveys different meanings. In this case, the affective meaning is “thing.” Also, “What a<br />

worthless piece of crap!”<br />

12. Niños, probablemente <strong>de</strong>l pipil “tsipit” que significa “maíz inmaduro, bebé”<br />

13. Quizás influencia <strong>de</strong>l asturiano: abuelo = güelo.<br />

14. There is no natural way in English to substitute “Mister” as “Ño” for “Señor” in Spanish. An alternative<br />

could be “Mister B” or “‘ster”, but some of my informants found these expressions unnatural.<br />

15. Huarache en México.<br />

16. Exclamación que indica sorpresa o <strong>de</strong>sprecio.<br />

17. Aféresis <strong>de</strong> “señor.”<br />

18. Caite (/ka-ee-tay/) is a sandal ma<strong>de</strong> of used tires, leather and other materials worn by peasants.

—¡Comolóis!<br />

Bashuto se prendió al puro con toda<br />

la fuerza <strong>de</strong> sus arrugas, y se fue en<br />

humo. Enseguiditas contó mil hallazgos<br />

<strong>de</strong> botijas, todos los cuales “él bía<br />

prisenciado con estos ojos”. Cuando se<br />

fue, se fue sin darse cuenta <strong>de</strong> que, <strong>de</strong><br />

lo dicho, <strong>de</strong>jaba las cáscaras.<br />

Como en esos días se murió la Petrona<br />

Pulunto, José levantó la boca y la<br />

llevó caminando por la vecindad, sin<br />

resultados nutritivos. Comió majonchos<br />

robados, y se <strong>de</strong>cidió a buscar botijas.<br />

Para ello, se puso a la cola <strong>de</strong> un arado<br />

y empujó. Tras la reja iban arando sus<br />

ojos. Y así fue como José Pashaca llegó<br />

a ser el indio más holgazán y a la vez<br />

el más laborioso <strong>de</strong> todos los <strong>de</strong>l lugar.<br />

Trabajaba sin trabajar —por lo menos<br />

sin darse cuenta— y trabajaba tanto,<br />

que las horas coloradas le hallaban<br />

siempre sudoroso, con la mano en la<br />

mancera y los ojos en el surco.<br />

Piojo <strong>de</strong> las lomas, caspeaba ávido la<br />

tierra negra, siempre mirando al suelo<br />

con tanta atención, que parecía como<br />

si entre los borbollos <strong>de</strong> tierra hubiera<br />

ido <strong>de</strong>jando sembrada el alma. Pa<br />

que nacieran perezas; porque eso sí,<br />

Pashaca se sabía el indio más sin oficio<br />

<strong>de</strong>l valle.<br />

21<br />

“That’s what I just said!”<br />

Bashuto sucked on his cigar with all<br />

the might of his wrinkles, and his<br />

thoughts were lost in the smoke. Then<br />

he procee<strong>de</strong>d to tell of a thousand<br />

discoveries of the magical jugs, all<br />

of which “he had witnessed with his<br />

own two eyes.” When he left, he did<br />

so without realizing that shells of his<br />

stories were left behind with José.<br />

Petrona Pulunto died around that<br />

time, causing José to scrounge around<br />

the neighborhood for food, without<br />

profitable results. He stole majonchos 19<br />

to eat, and <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to look for the<br />

mythical jugs. He put himself behind a<br />

plow and pushed. His eyes were plowing<br />

behind the bla<strong>de</strong>. That was how José<br />

Pashaca became the laziest but, at the<br />

same time, the most hardworking of all<br />

men in the area. He worked without<br />

working, at least without realizing<br />

it, and he worked so much that the<br />

reddish hours of sunset always found<br />

him sweaty, with one hand still on the<br />

plow and his eyes still on the rows.<br />

Like the louse of the hills he hungrily<br />

examined the black dirt, always looking<br />

at the ground with such attention that<br />

it seemed as if he had planted his soul<br />

in those clods of dirt. He was unwilling<br />

to work; and there was no doubt that<br />

Pashaca thought he was the least<br />

hardworking person in the valley.<br />

19. Majoncho (ma-hon-cho/) is a variety of banana that is grown in tropical areas. It is smaller that the<br />

regular banana but with more culinary uses due to its high levels of starch.

Él no trabajaba. Él buscaba las botijas<br />

llenas <strong>de</strong> bambas doradas, que hacen<br />

“¡plocosh!” cuando la reja las topa, y<br />

vomitan plata y oro, como el agua <strong>de</strong>l<br />

charco cuando el sol comienza a ispiar<br />

<strong>de</strong>trás <strong>de</strong> lo <strong>de</strong>l ductor Martínez, que<br />

son los llanos que topan al cielo.<br />

Tan gran<strong>de</strong> como él se hacía, así se hacía<br />

<strong>de</strong> gran<strong>de</strong> su obsesión. La ambición<br />

más que el hambre, le había parado <strong>de</strong>l<br />

cuero y lo había empujado a las la<strong>de</strong>ras<br />

<strong>de</strong> los cerros; don<strong>de</strong> aró, aró, <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> la<br />

gritería <strong>de</strong> los gallos que se tragan las<br />

estrellas, hasta la hora en que el güas<br />

ronco y lúgubre, parado en los ganchos<br />

<strong>de</strong> la ceiba, puya el silencio con sus<br />

gritos <strong>de</strong>stemplados.<br />

Pashaca se peleaba las lomas. El<br />

patrón, que se asombraba <strong>de</strong>l milagro<br />

que hiciera <strong>de</strong> José el más laborioso<br />

colono24 , dábale con gusto y sin medida<br />

luengas tierras, que el indio soñador<br />

<strong>de</strong> tesoros rascaba con el ojo presto a<br />

dar aviso en el corazón, para que éste<br />

cayera sobre la botija como un trapo <strong>de</strong><br />

amor y ocultamiento.<br />

Y Pashaca sembraba, por fuerza,<br />

porque el patrón exigía los censos.<br />

22<br />

He didn’t work. He looked for botijas<br />

filled with gol<strong>de</strong>n bambas 20 that, when<br />

hit by the plow make a “plocosh” sound,<br />

and regurgitate silver and gold, like the<br />

sparkling water in the puddle when the<br />

sun begins to spy behind the plains that<br />

touch the sky, those plains that belong<br />

to Doctah Martínez. 21<br />

As he grew more powerful, so did his<br />

obsession. Greed, more than hunger,<br />

had enlivened his body and had driven<br />

him to the slopes of the hills. There he<br />

plowed and plowed from the roosters’<br />

crow that swallow the stars, until the<br />

time in which the laughing falcon, 22<br />

bellowing and lugubrious, perched in<br />

the branches of the ceiba 23 trees breaks<br />

the silence with its discordant racket.<br />

Pashaca fought for the hills. His boss,<br />

astonished by the miracle that ma<strong>de</strong><br />

José the most hardworking tenantfarmer,<br />

happily assigned him an<br />

unlimited number of large land parcels.<br />

José, dreaming of treasures, plowed<br />

with his eyes peeled for the jug that<br />

would make his heart happy, and<br />

surround the jug like a cloth of love and<br />

protection.<br />

Pashaca planted because he had to and<br />

because the boss <strong>de</strong>man<strong>de</strong>d the counts.<br />

20. Coins used in the 19th century. They were the size of a silver dollar.<br />

21. I <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to keep “spy” for “ispiar” because of the historic reference of “Ductor Martínez” who used<br />

to keep an eye on the people and their territories that were a communist menace. William Stanley sums<br />

it: “Shortly after the Matanza, Martínez established new mechanisms of state control throughout the<br />

country, but with particular impact in rural areas.” (1996: 58)<br />

22. A bird that makes an unpleasant loud noise.<br />

23. Also known as “kapok,” this tree was a sacred symbol for the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica.<br />

24. RAE: colono, na. (Del lat. colonus, <strong>de</strong> colere, cultivar). 2. m. y f. Labrador que cultiva y labra una heredad<br />

por arrendamiento y suele vivir en ella.

Por fuerza también tenía Pashaca<br />

que cosechar, y por fuerza que cobrar<br />

el grano abundante <strong>de</strong> su cosecha,<br />

cuyo producto iba guardando<br />

<strong>de</strong>spreocupadamente en un hoyo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

rancho, por siacaso.<br />

Ninguno <strong>de</strong> los colonos se sentía con<br />

hígado suficiente para llevar a cabo una<br />

labor como la <strong>de</strong> José. “Es el hombre<br />

<strong>de</strong> jierro”, <strong>de</strong>cían; “en<strong>de</strong> 25 que le entró<br />

asaber qué, se propuso hacer pisto. Ya<br />

tendrá una buena huaca... ” 26<br />

Pero José Pashaca no se daba cuenta<br />

<strong>de</strong> que, en realidad, tenía huaca. Lo<br />

que él buscaba sin <strong>de</strong>smayo era una<br />

botija, y siendo como se <strong>de</strong>cía que las<br />

enterraban en las aradas, allí por fuerza<br />

la incontraría tar<strong>de</strong> o temprano.<br />

Se había hecho no sólo trabajador, al<br />

ver <strong>de</strong> los vecinos, sino hasta generoso.<br />

En cuanto tenía un día <strong>de</strong> no po<strong>de</strong>r arar,<br />

por no tener tierra cedida, les ayudaba<br />

a los otros, les mandaba <strong>de</strong>scansar y se<br />

quedaba arando por ellos. Y lo hacía<br />

bien: los surcos <strong>de</strong> su reja iban siempre<br />

pegaditos, chachados 28 y projundos,<br />

que daban gusto.<br />

23<br />

He also had to gather the harvest,<br />

and he had to receive the abundant<br />

pay. Without concern, he amassed<br />

his remuneration in a hidy-hole in his<br />

shack, just in case.<br />

No other farmer felt brave enough to<br />

work as hard as José. “He’s an iron man,”<br />

they said; “What’s with José, sud<strong>de</strong>nly<br />

he’s making big bucks. He must have a<br />

big stash27 by now…”<br />

But José Pashaca did not realize that he<br />

actually had money. What he looked for<br />

relentlessly was a botija, and because it<br />

was said that they were buried in the<br />

fields, he felt that he must find it there<br />

sooner or later.<br />

According to his neighbors, he had<br />

become not only hardworking but<br />

even generous. When he ran out of his<br />

own land to plow, he helped others. He<br />

told them to go rest, and stayed there<br />

plowing for them. He did it well: the<br />

rows of his plow were always parallel, 29<br />

perfectly spaced and very <strong>de</strong>ep. It was<br />

a pleasure to look at those furrows.<br />

25. Arcaismo <strong>de</strong> “<strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong>” o “por lo cual”.<br />

26. Según la RAE, guaca. (Del quechua waca, dios <strong>de</strong> la casa). 1. f. Sepulcro <strong>de</strong> los antiguos indios,<br />

principalmente <strong>de</strong> Bolivia y el Perú, en que se encuentran a menudo objetos <strong>de</strong> valor. 2. f. En América<br />

Central y gran parte <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>l Sur, sepulcro antiguo indio en general. 3. f. Am. Mer. y Hond. Tesoro<br />

escondido o enterrado. 4. f. C. Rica y Nic. Conjunto <strong>de</strong> objetos escondidos o guardados. 5. f. C. Rica,<br />

Cuba, Hond. y Nic. Hoyo don<strong>de</strong> se <strong>de</strong>positan frutas ver<strong>de</strong>s para que maduren. 6. f. C. Rica y Cuba. Hucha<br />

o alcancía. 7. f. coloq. Cuba. Dinero ahorrado que se guarda en casa. 8. f. El Salv. y Pan. En las sepulturas<br />

indígenas, vasija, generalmente <strong>de</strong> <strong>barro</strong> cocido, don<strong>de</strong> aparecen <strong>de</strong>positados joyas y objetos artísticos.<br />

9. f. Nic. escondite (lugar para escon<strong>de</strong>r o escon<strong>de</strong>rse).<br />

27. Stash: huaca in Salvadoran Spanish. My mother recalls that el<strong>de</strong>rs in her youth talked about their<br />

ancestors having unearthed “a treasure” hid<strong>de</strong>n insi<strong>de</strong> an earthenware jug.<br />

28. Según la RAE: chacho2, cha. (Quizá <strong>de</strong>l nahua chachacatl). 1. adj. El Salv. y Hond. Dicho <strong>de</strong> dos cosas,<br />

especialmente <strong>de</strong> dos frutas: Que están pegadas.<br />

29. Campbell: “chachawa-t,” double or twin. (182)

—¡On<strong>de</strong> te metés, babosada! —pensaba<br />

el indio sin darse por vencido—: Y tei <strong>de</strong><br />

topar, aunque no querrás, así mihaya<br />

<strong>de</strong> tronchar en los surcos.<br />

Y así fue; no lo <strong>de</strong>l encuentro, sino lo <strong>de</strong><br />

la tronchada.<br />

Un día, a la hora en que se ver<strong>de</strong>ya el<br />

cielo y en que los ríos se hacen rayas<br />

blancas en los llanos, José Pashaca se<br />

dio cuenta <strong>de</strong> que ya no había botijas.<br />

Se lo avisó un <strong>de</strong>smayo con calentura;<br />

se dobló en la mancera; los bueyes<br />

se fueron parando, como si la reja se<br />

hubiera enredado en el raizal <strong>de</strong> la<br />

sombra. Los hallaron negros, contra<br />

el cielo claro, “voltiando a ver al indio<br />

embruecado, y resollando el viento<br />

oscuro”.<br />

José Pashaca se puso malo. No quiso<br />

que nai<strong>de</strong>31 lo cuidara. “Den<strong>de</strong>32 que<br />

bía finado la Petrona, vivía íngrimo en su<br />

rancho.”<br />

Una noche, haciendo fuerzas <strong>de</strong> tripas,<br />

salió sigiloso llevando, en un cántaro<br />

viejo, su huaca. Se agachaba <strong>de</strong>trás<br />

<strong>de</strong> los matochos cuando óiba ruidos,<br />

y así se estuvo haciendo un hoyo con<br />

la cuma33 . Se quejaba a ratos, rendido,<br />

pero luego seguía con brío su tarea.<br />

30. Image that is repeated later: sky turns green, not blue.<br />

31. Arcaismo <strong>de</strong> “nadie”.<br />

32. Arcaismo <strong>de</strong> “<strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong>”.<br />

33. RAE: cuma. 1. f. Am. Cen. Cuchillo corvo para rozar y podar.<br />

24<br />

“Where is you hiding, stupid thing!”<br />

he thought without giving up: “and I’ll<br />

find you, even though you don’t want<br />

me to, even if I need to break my back<br />

plowing in the furrows.”<br />

And that’s what happened; not the<br />

finding, but the breaking.<br />

One day, at the hour when the sky<br />

turns green 30 and the rivers become<br />

white lines on the plains, José Pashaca<br />

realized that there weren’t any more<br />

botijas. Finally a sign: he broke down<br />

in the field, he fainted with fever. The<br />

oxen slowed down as if the bla<strong>de</strong><br />

became entangled in the roots of the<br />

shadow. They were found silhouetted<br />

by the clear sky, “staring down at the<br />

fallen man who was heavily breathing<br />

the dark wind.”<br />

José Pashaca became very ill. He didn’t<br />

want anyone to take care of him. “He<br />

lived all alone in his shack since Petrona<br />

had died.”<br />

One night, he plucked up his courage.<br />

He went out stealthily carrying<br />

his money in an old clay jug. He<br />

began to dig a hole with his curved<br />

machete. Whenever he heard noises<br />

he ducked down in the bushes. He<br />

moaned at times, exhausted, but with<br />

<strong>de</strong>termination continued his task.

Metió en el hoyo el cántaro, lo tapó<br />

bien tapado, borró todo rastro <strong>de</strong> tierra<br />

removida; y alzando sus brazos <strong>de</strong><br />

bejuco hacia las estrellas, <strong>de</strong>jó ir liadas<br />

en un suspiro estas palabras:<br />

—¡Vaya: pa que no se diga que ya nuai<br />

botijas en las aradas!...<br />

25<br />

He put the treasure in the hole; he<br />

covered it well, brushing away all traces<br />

of removed dirt. José stretched his<br />

branch-like arms towards the stars and<br />

spoke these words, wrapped in a sigh:<br />

“A’wright, so now nobody can’t say there<br />

ain’t no more botijas in the fields!”

la HoNra<br />

Había amanecido nortiando; la Juanita<br />

limpia lagua helada; el viento llevaba<br />

zopes34 y olores. Atravesó el llano. La<br />

nagua se le amelcochaba y se le hacía<br />

calzones. El pelo le hacía alacranes<br />

negros en la cara. La Juana iba bien<br />

contenta, chapudita35 y apagándole<br />

los ojos al viento. Los árboles venían<br />

corriendo. En medio <strong>de</strong>l llano la<br />

cogió un tumbo <strong>de</strong> norte. La Juanita<br />

llenó el frasco <strong>de</strong> su alegría y lo tapó<br />

con un grito; luego salió corriendo y<br />

enredándose en su risa. La chucha36 iba<br />

ladrando a su lado, queriendo alcanzar<br />

las hojas secas que pajareaban.<br />

El ojo diagua estaba en el fondo<br />

<strong>de</strong> una barranca, sombreado por<br />

quequeishques38 39 y palmitos.<br />

26<br />

THe HoNor<br />

It had been windy well before dawn;<br />

Juana37 was clean; the water was cold;<br />

the wind carried vultures and scents<br />

across the plain. Her skirt whirled<br />

around her so that it became one with<br />

her body. Her hair was lashing into her<br />

face like black scorpions. Juana walked<br />

with a happy bounce in her step. Her<br />

blushing cheeks caused the wind to<br />

close its eyes. The trees seemed to<br />

be running towards her, while in the<br />

middle of the valley she was caught by<br />

the northern gale. Juana filled up the<br />

bottle with her happiness and covered<br />

it with a cry; then, running and being<br />

swaddled in her laughter, she left. Her<br />

dog was barking by her si<strong>de</strong> trying to<br />

catch the dry leaves that were flying<br />

like birds.<br />

The spring was at the end of a ravine,<br />

sha<strong>de</strong>d by quequeishque40 41 vines and<br />

small palms.<br />

34. RAE: nahua “tzopílotl”; Campbell: pipil “sope, kusma”.<br />

35. Con mejillas rosadas.<br />

36. “Perra” en español salvadoreño.<br />

37. Salarrué uses proper names and their diminutive as well; however this technique does not work in<br />

English as it tends to confuse the rea<strong>de</strong>r who thinks that “Juana” and “Juanita” are two different characters.<br />

This is also applicable to later stories.<br />

38. Xanthosoma mexicanum. Es una planta trepadora, no hay que confundirla con la raíz “quequisque”<br />

39. Ramírez-Sosa: Aroid (Xanthosoma mexicanum, Araceae). Una planta herbácea con hojas en forma<br />