chj-summer-2004

chj-summer-2004

chj-summer-2004

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

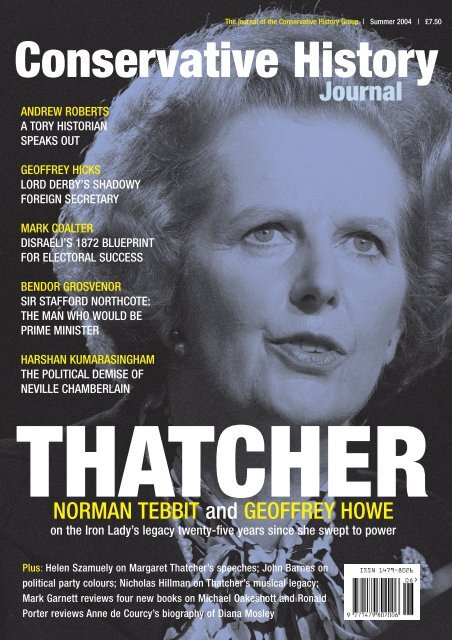

Conservative History<br />

ANDREW ROBERTS<br />

A TORY HISTORIAN<br />

SPEAKS OUT<br />

GEOFFREY HICKS<br />

LORD DERBY’S SHADOWY<br />

FOREIGN SECRETARY<br />

MARK COALTER<br />

DISRAELI’S 1872 BLUEPRINT<br />

FOR ELECTORAL SUCCESS<br />

BENDOR GROSVENOR<br />

SIR STAFFORD NORTHCOTE:<br />

THE MAN WHO WOULD BE<br />

PRIME MINISTER<br />

HARSHAN KUMARASINGHAM<br />

THE POLITICAL DEMISE OF<br />

NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN<br />

The journal of the Conservative History Group | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | £7.50<br />

Journal<br />

THATCHER<br />

NORMAN TEBBIT and GEOFFREY HOWE<br />

on the Iron Lady’s legacy twenty-five years since she swept to power<br />

Plus: Helen Szamuely on Margaret Thatcher’s speeches; John Barnes on<br />

political party colours; Nicholas Hillman on Thatcher’s musical legacy;<br />

Mark Garnett reviews four new books on Michael Oakeshott and Ronald<br />

Porter reviews Anne de Courcy’s biography of Diana Mosley

Contents<br />

Conservative History Journal<br />

The Conservative History Journal is published twice<br />

yearly by the Conservative History Group<br />

ISSN 1479-8026<br />

Advertisements<br />

To advertise in the next issue<br />

call Helen Szamuely on 07733 018999<br />

Editorial/Correspondence<br />

Contributions to the Journal – letters, articles and<br />

book reviews are invited. The Journal is a refereed<br />

publication; all articles submitted will be reviewed<br />

and publication is not guaranteed. Contributions<br />

should be emailed or posted to the addresses below.<br />

All articles remain copyright © their authors<br />

Subscriptions/Membership<br />

An annual subscription to the Conservative History<br />

Group costs £15. Copies of the Journal are included<br />

in the membership fee.<br />

The Conservative History Group<br />

Chairman: Keith Simpson MP<br />

Deputy Chairman: Professor John Charmley<br />

Director: Iain Dale<br />

Treasurer: John Strafford<br />

Secretary: Martin Ball<br />

Membership Secretary: Peter Just<br />

Journal Editors: John Barnes & Helen Szamuely<br />

Committee:<br />

Christina Dykes<br />

Lord Norton of Louth<br />

Lord Brooke<br />

Jonathan Collett<br />

Simon Gordon<br />

Mark Garnett<br />

Ian Pendlington<br />

David Ruffley MP<br />

Quentin Davies MP<br />

William Dorman<br />

Graham Smith<br />

Jeremy Savage<br />

Lord Henley<br />

William McDougall<br />

Tricia Gurnett<br />

Conservative History Group<br />

PO Box 42119<br />

London<br />

SW8 1WJ<br />

Telephone: 07768 254690<br />

Email: info@conservativehistory.org.uk<br />

Website: www.conservativehistory.org.uk<br />

Contents<br />

Definitely not a farewell 1<br />

Iain Dale<br />

Good try, but must do better 2<br />

Helen Szamuely<br />

A Tory historian speaks out 3<br />

Helen Szamuely talks to Andrew Roberts<br />

Thatcher 7<br />

Norman Tebbit and Geoffrey Howe on the Iron Lady’s legacy<br />

Hilda’s Cabinet Band 9<br />

Nicholas Hillman<br />

A strangely familiar voice 12<br />

Helen Szamuely<br />

The political demise of Neville Chamberlain 13<br />

Harshan Kumarasingham<br />

Capturing the middle ground:<br />

Disraeli’s 1872 Blueprint for electoral success 17<br />

Mark Coalter<br />

Lord Derby’s shadowy Foreign Secretary 22<br />

Geoffrey Hicks<br />

The man who would be Prime Minister:<br />

Sir Stafford Northcote Bart 24<br />

Bendor Grosvenor<br />

Party colours 27<br />

John Barnes<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Mark Garnett on four new books about Michael Oakshott 30<br />

Diana Mosley by Anne de Courcy 31<br />

reviewed by Ronald Porter<br />

www.conservativehistory.org.uk

Definitely not a farewell<br />

Iain Dale<br />

A<br />

fter a mere two isues I have decided<br />

to step down as co-editor of the<br />

Conservative History Journal but I<br />

am delighted that Helen Szamuely<br />

has agreed to step into the breach.<br />

She will bring a degree of thoroughness and historical<br />

perspective which I could never match. While I<br />

shall remain Director of the CHG I must devote my<br />

time now to my business and, perhaps more importantly,<br />

to winning back North Norfolk at the next<br />

election. This issue of the magazine is particularly<br />

important as it marks the 25th anniversary of the<br />

election of the Thatcher Government in May 1979. I<br />

remember it especially well as I stood as the<br />

Conservative Candidate in a mock election at my<br />

High School in Essex and romped home with a 27%<br />

majority over....the National Front! Margaret<br />

Thatcher inspired me to get involved in politics. In<br />

her day we used to win elections almost at will. I<br />

remember what it was like standing on people's<br />

doorsteps knowing that what I was doing was helping<br />

her retain power. It's that kind of pride which we<br />

Conservatives now have to instill into our party<br />

workers up and down the country. They have to know<br />

that Michael Howard and candidates like me are not<br />

only worth campaigning for but, once we are successful,<br />

we will do justice to the legacy which<br />

Margaret Thatcher has left us.<br />

Conservative History Group<br />

Party Conference Fringe<br />

William<br />

Hague<br />

will speak on<br />

William Pitt<br />

the Younger<br />

Iain Dale is the<br />

Conservative<br />

Parliamentary Spokesman<br />

for North Norfolk. Email<br />

him on iain@iaindale.com.<br />

Monday 4 October<br />

17.45–19.00<br />

Purbeck Bar in the Bournemouth International Conference Centre<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 1

Good try, but must do better<br />

Helen Szamuely<br />

It is not, perhaps, the most auspicious way to<br />

start one’s stint as co-editor of this Journal,<br />

having to apologize for the issue’s late appearance.<br />

All I can say in my self-defence is that<br />

the last few months have been a steep learning<br />

curve. However, that is all behind me and I hope that<br />

the quality of this and future issues will live up to the<br />

excellent reputation the Conservative History Journal<br />

deservedly acquired under Iain Dale’s editorship.<br />

Though a couple of months late we are celebrating<br />

in this issue the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first<br />

Thatcher government and we decided that the best<br />

way to do so would be to ask two of her colleagues,<br />

Lord Howe and Lord Tebbit, to give us their views on<br />

the phenomenon of Thatcherism. We are proud to<br />

present their insight along with a couple of other articles<br />

that cover other aspects of the subject.<br />

The fascinating, entertaining and instructive interview<br />

with Andrew Roberts, one of our leading historians,<br />

will, we hope be the first of a whole series of<br />

interviews on the subject of Conservative or Tory history.<br />

Roberts, a widely respected historian and a brilliant<br />

wordsmith, is also a supporter of the<br />

Conservative History Group and of this Journal.<br />

From the successful to the unsuccessful twentieth<br />

century Prime Minister. May also saw the anniverasry<br />

of the fall of Chamberlain’s government and with it<br />

the destruction of his political reputation. We have an<br />

article from an historian in New Zealand on those<br />

The Conservative History Group<br />

2 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

events and the theme of Churchill’s government is<br />

taken up by Ronald Porter, if somewhat obliquely, in<br />

his review of the latest biography of Diana Mosley.<br />

A characteristically entertaining piece by the co-editor<br />

of this Journal, John Barnes, deals with the important<br />

but somewhat neglected subject of party colours.<br />

Conservative history has to look beyond the twentieth<br />

century and there is a section in this issue on<br />

Disraeli, another great Conservative Prime Minister<br />

and two of his colleagues. In future editions we hope<br />

to cover many other aspects of Conservative and Tory<br />

history and historiography, going back certainly to the<br />

eighteenth but, even, the seventeenth century.<br />

We hope to write about Conservative political<br />

thought as in the review of several books on Michael<br />

Oakeshott and we shall have entertaining and, who<br />

knows, perhaps slightly scurrillous pieces about Tory<br />

and Conservative politicians, as well as forgotten or<br />

little known aspects of party history. We have great<br />

plans to expand our subject matter to include subjects<br />

to do with Conservative history in the United States<br />

and the Commonwealth countries.<br />

The next issue will appear at the end of September<br />

- timing will be constrained by the Party Conference<br />

- and thereafter the Journal will be published twice<br />

yearly at the end of March and September. We are<br />

looking for contributions, articles, ideas, suggestions.<br />

The Conservative History Journal had a great start.<br />

After a slight hiccup it will have a great future.<br />

As the Conservative Party regroups after two general election defeats, learning from history is perhaps more vital than ever, We formed the<br />

Conservative History Group in the Autumn of 2002 to promote the discussion and debate of all aspects of Conservative history. We have<br />

organised a wide-ranging programme of speaker meetings in our first year and with the bi-annual publication of the Conservative History<br />

Journal, we hope to provide a forum for serious and indepth articles on Conservative history, biographies of leading and more obscure<br />

Conservative figures, as well as book reviews and profiles. For an annual subscription of only £15 you will receive invites to all our events as<br />

well as complimentary copies of the Conservative History Journal twice a year. We very much hope you will want to join us and become part<br />

of one of the Conservative Party's most vibrant discussion groups.<br />

Please fill in and return this form if you would like to join the Conservative History Group<br />

Name ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Address _________________________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Email ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Telephone _______________________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Send your details with your subscription of £15 to Conservative History Group, PO Box 42119, London SW8 1WJ<br />

Or you can join online at www.politicos.co.uk<br />

Helen Szamuely is the new<br />

co-editor of the Conservative<br />

History Journal. Email her<br />

on szamuely@aol.com.

A Tory historian<br />

speaks . . .<br />

In the first of a new series of interviews with<br />

Conservative historians Helen Szamuely<br />

meets Andrew Roberts<br />

Andrew Roberts is one of the new<br />

group of historians that has made<br />

modern British historiography internationally<br />

respected and domestically<br />

popular. As a man of the right, he<br />

has had various insults heaped on<br />

him by the more left-leaning media.<br />

Among other things he has been<br />

called a warmonger, an extremist<br />

(naturally) and a conservative historian,<br />

thus implying that his writings<br />

lack objectivity. Noticeably, none of<br />

the detractors have managed to point<br />

to any lack of research or objectivity<br />

but this has not lessened their ardour.<br />

Mr Roberts says that he is a Tory<br />

rather than a Conservative and<br />

insists that there is no such thing as a<br />

conservative historian. But he is<br />

proud of his political views (understandably)<br />

and is active in a number<br />

of organizations, such as the Bruges<br />

Group, the Freedom Association, the<br />

British Weights and Measures<br />

Association and the Centre for Policy<br />

Studies. What they all have in common<br />

is a high regard for the traditional<br />

liberties that have long been<br />

associated with Britain and the<br />

British people and are now under<br />

threat from inside and outside. Here<br />

Andrew Roberts gives his views on<br />

history, its study and its writing, as<br />

well as politics to Helen Szamuely.<br />

HS: Andrew, thank you very much for<br />

agreeing to this interview. To start<br />

with, let’s go back to basics, as a certain<br />

Conservative Prime Minister<br />

once said.<br />

AR: You’re right to say that he was a<br />

Conservative Prime Minister but he<br />

was not in any sense a Tory Prime<br />

Minister.<br />

HS: That is very true, of course. Let’s<br />

say a Prime Minister who led the<br />

Conservative Party, though I suppose<br />

we could quibble about that as well.<br />

AR: I think the word “leadership” is<br />

something I would pick you up on.<br />

Sorry.<br />

HS: Well, let us get past that one. You<br />

have been described by friend and<br />

foe, and we are definitely friends, as<br />

a “conservative historian”. Would<br />

you describe yourself as a “conservative<br />

historian”?<br />

AR: No, I emphatically would not. I<br />

think that the methods that conservatives<br />

as historians use, should be precisely<br />

the same as those used by a<br />

socialist or a whig or a marxist. We<br />

have to use exactly the same rigorous<br />

level of objectivity and so to be<br />

described as an historian who is coming<br />

from any angle at all is, I think,<br />

damaging and unfair. However, I am<br />

an historian who is a Conservative.<br />

And I am also an historian who writes<br />

more often about Conservatives and<br />

Conservative governments than other<br />

kinds, but I think that once you<br />

attempt to pigeonhole an historian for<br />

his political views you get into very<br />

dangerous territory with regards to<br />

his objectivity, which is an absolute<br />

prerequisite for his professionalism.<br />

HS: So, would you say that there is no<br />

such thing as Conservative history<br />

writing. Most people would know<br />

what we mean by Whig history writing.<br />

Is there a similar idea of<br />

Conservative history writing?<br />

AR: This is a very interesting point.<br />

Very roughly, Whigs believe in a<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 3

Andrew Roberts<br />

sense of progress, Marxists believe<br />

in dialectical materialism and class<br />

warfare and there is, in my view, a<br />

strand of Tory historicism, or historiography,<br />

in which mankind is not<br />

seen as moving towards any preordained<br />

end and is certainly not seen<br />

as moving in any straight direction<br />

either. History, in my view, zig-zags.<br />

Instead of being a locomotive that is<br />

moving to a destination, it can be<br />

shunted into sidings as it was, for<br />

instance, between 1914 and 1989; it<br />

can go into reverse as it has done<br />

several times. I think that should be<br />

the Tory philosophy of history.<br />

Without getting too much into<br />

semantics, the words Tory and<br />

Conservative, I have always<br />

believed, should be kept rigidly<br />

apart. The way they are interchangeable<br />

in journalism, I think, does the<br />

Tories a great disservice because the<br />

Conservative party in parliament - in<br />

opposition as well as in government<br />

- very rarely sticks to rigid Tory<br />

principles, more’s the shame. And it<br />

is possible to be a Tory, as one could<br />

be between November 1990 and<br />

May 1997, without believing that<br />

the Conservative party is doing very<br />

much good.<br />

HS: If you look back on historians of<br />

the past, whom would you describe<br />

as Tory historians?<br />

AR: Interestingly, several of the ones<br />

I would call Tory historians, would<br />

not have considered themselves to<br />

be Tories or, indeed, Conservatives.<br />

But I would look to the people, who<br />

really stand up against whiggish and<br />

marxist views of history. I’d mention<br />

Norman Stone, J.D.C.Clark,<br />

Maurice Cowling, Niall Ferguson,<br />

going back a bit, I think Edward<br />

Gibbon, G.R.Elton, Hugh Dacre,<br />

A.L.Rowse, and others. People,<br />

who, like me, do not believe that<br />

mankind is on a natural progression<br />

to the betterment or the brotherhood<br />

of man.<br />

HS: Most people would mention<br />

Lord Acton. What is your view on<br />

him?<br />

4 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

AR: His History of Liberty was<br />

one of the great unwritten books of<br />

the world. Had he written a major<br />

work of history, I think it would<br />

have been one that would have<br />

emphasised the dangers and the<br />

threats to liberty as much as the<br />

benefits.<br />

HS: A lot of people would say: oh<br />

yes, Tories, they do not, unlike, say<br />

Whigs or Liberals, believe in the<br />

concept of freedom, of liberty.<br />

Would you consider liberty an<br />

important subject for Tory historiography?<br />

AR: I think it very much is and it is a<br />

great shame that nobody of Acton’s<br />

stature has written a history of liberty.<br />

Nor is there a particularly good<br />

biography of John Wilkes, the early<br />

progenitor of eighteenth century liberty.<br />

What men then called a real<br />

and manly liberty. I would like to<br />

take issue with you over the idea that<br />

we as Tories think more about order<br />

and established power than liberty. I<br />

think, for example, that John<br />

Hampden was a Tory before the<br />

Tory party came into existence and I<br />

think that there is a very, very strong<br />

tradition, especially in terms of<br />

jurisprudence, a very strong Tory<br />

belief in the kind of liberty that is<br />

enunciated in the English<br />

Revolution and in the common law.<br />

What common law gives us - and it<br />

is, of course, now under threat from<br />

New Labour and from the European<br />

Union - is a massive ancient codification<br />

of customs and traditions and<br />

precedent, that does not circumscribe<br />

a Briton’s liberty but allows<br />

him to act in a way that does not<br />

damage or threaten his neighbour.<br />

And you can’t get more Tory than<br />

that.<br />

HS: I think we’ll stick to the word<br />

“Tory”. Once you start getting on to<br />

the Conservative Party and the<br />

notion of “conservative” with a<br />

small “c”, you get into serious<br />

problems. Some of the most conservative<br />

organizations are actually<br />

socialist.<br />

AR: Precisely. Nothing was more<br />

conservative than the National Union<br />

of Mineworkers, for example.<br />

HS: Except, maybe the TUC. This<br />

brings us rather neatly to the<br />

Thatcher government. With a bit of<br />

luck when this issue of the Journal<br />

comes out, we shall be celebrating,<br />

or, perhaps, some people will be<br />

mourning, the twenty-fifth anniversary<br />

of Mrs Thatcher winning her<br />

first election. If you were to write the<br />

history of the Thatcher government,<br />

not perhaps now, but, say in ten<br />

years’ time, how would you approach<br />

it? What would be the good things<br />

you’d say about it, what would be the<br />

not so good things?<br />

AR: My view is that the book cannot<br />

be written until the thirty year rule is<br />

up for the 1979 to 1990 period. So it<br />

“ History, in my view, zig-zags. Instead<br />

of being a locomotive that is moving to<br />

a destination, it can be shunted into<br />

sidings as it was, for instance, between<br />

1914 and 1989; it can go into reverse<br />

as it has done several times ”<br />

can’t even be researched until January<br />

2011. And after that it would take a<br />

good four or five years just to work<br />

your way through the various papers.<br />

I think that an intelligent biographer<br />

of Mrs Thatcher - and luckily we<br />

have Charles Moore doing that, a perfect<br />

example of a Tory who isn’t<br />

always a Conservative - of her government<br />

as well as of her, will look at<br />

the fascinating dichotomy between<br />

rhetoric and practice, which happens<br />

in every government, of course, but<br />

was there even more startlingly with<br />

Margaret Thatcher. Her rhetoric was<br />

so powerful and so, too, was her practice,<br />

but there were several occasions<br />

(one thinks of the threat of the miners’<br />

strike in 1981, for instance) when<br />

she backed down. And she had been<br />

much tougher in opposition on subjects<br />

like Rhodesia and immigration

than she turned out to be when she<br />

got into power. So I think there is an<br />

angle for a Tory historian to take<br />

Margaret Thatcher to task from the<br />

Right and to ask what happened to<br />

many of the hopes. However, one has<br />

to remember at all times that she was<br />

five hundred per cent better than anyone<br />

could have possibly hoped for in<br />

any political period for the Tories<br />

from 1945 up to her election in 1975.<br />

It was an astonishing stroke of luck<br />

that she won the party leadership and<br />

although an historian must be objective,<br />

that element of luck is a very<br />

important one. I am just about to publish<br />

a book called What Might Have<br />

Been, which is going to talk about the<br />

power of luck in history. We have<br />

some good Tories writing for it. I am<br />

thinking of Simon Heffer, Norman<br />

Stone, Conrad Black, David Frum.<br />

Though it is not a Conservative or a<br />

right-wing book, it does have a few<br />

“ I think there is an angle for a Tory<br />

historian to take Margaret Thatcher to<br />

task from the Right and to ask what<br />

happened to many of the hopes ”<br />

sound people writing for it and it does<br />

bring it home to me again and again,<br />

the element of luck. Simon Heffer<br />

writes about Margaret Thatcher being<br />

blown up in Brighton and what would<br />

have happened had she died back in<br />

1984. When one thinks of those years<br />

from 1979 to 1990, any number of<br />

chance occurrences could have<br />

derailed the Thatcher experiment. We<br />

see it, perhaps because it also<br />

spanned the decade of the eighties, as<br />

a great monolithic, almost predestined,<br />

ministry.<br />

HS: Yes, there is a tendency to<br />

emphasise that, partly by her and<br />

partly by that famous story of<br />

Callaghan’s about him driving home<br />

on the night of the election and saying<br />

that it did not matter, there was<br />

nothing he could do, there was a<br />

wind blowing the other way; but that<br />

is not at all how one remembers the<br />

election of 1979: not as a predestined<br />

event but just as another election.<br />

Most of us, I think, except maybe the<br />

few people close to Margaret<br />

Thatcher, probably did not realize<br />

that this was going to be a very different<br />

premiership.<br />

AR: No, that’s right. I am rather sceptical<br />

of what Jim Callaghan said<br />

because … well, first of all, a losing<br />

politician is going to blame what T. S.<br />

Eliot called “the vast impersonal<br />

forces” for his defeat. But, in fact,<br />

when one looks at general elections,<br />

any number of tiny, perhaps at the<br />

time inconsequential factors, could<br />

be playing on the minds of the electorate.<br />

Pollsters should be really<br />

quizzing people as they come out of<br />

the polling booths, not the day before<br />

elections or the day before that, but as<br />

they come out. They should be asking<br />

people precisely what mattered to<br />

them, why they voted and instead of<br />

giving them lists to choose from,<br />

where the person automatically<br />

chooses the most high-minded reason,<br />

they should simply wait until<br />

they get the reply. We do this a bit<br />

with book-buying. When somebody<br />

comes out of a bookshop, he might be<br />

asked by a polling organization: was<br />

it the review; was it the front cover;<br />

was it the fact that he had read the<br />

author before; what was the reason<br />

for buying this book. And the results<br />

you get are very very different usually<br />

from the ones you are expecting.<br />

People go into bookshops and buy<br />

completely different books from the<br />

one they were intending to as they<br />

walk through. And I wonder to what<br />

extent that is true of politics that people<br />

wind up at the end of an election<br />

campaign voting in a completely different<br />

way from the way they were<br />

intending to at the beginning of it. So<br />

when people get very aerated about<br />

things a year or two before the campaign,<br />

I wonder to what extent those<br />

kind of issues really matter compared<br />

to the ones that are actually being<br />

fought over during the campaign<br />

itself. There ought to be really serious<br />

and practical studies of this, but if<br />

there are I haven’t read any.<br />

Andrew Roberts<br />

HS: I haven’t seen any. Questions tend<br />

to be along the lines of would you<br />

agree to pay more tax if the money<br />

went to the health service and everybody<br />

says yes and then votes for the<br />

party that says no more tax rises.<br />

AR: Well, I consider that a very<br />

healthy thing, of course. Hypocrisy to<br />

pollsters is a very emotionally uplifting<br />

concept.<br />

HS: It is. And I think most people<br />

have got to the stage of not telling<br />

pollsters the truth. Just to go back to<br />

history as a subject. We are in a very<br />

strange situation in this country in<br />

that the teaching of history has virtually<br />

died out in schools. Certainly, in<br />

the state sector it is hardly ever taught<br />

and in some universities, when one<br />

looks at what they teach one shudders.<br />

At the same time, the writing of<br />

history and the reading of history<br />

have become very popular. People<br />

buy books, people watch serious programmes<br />

about history. How do you<br />

see the connection between these two<br />

developments?<br />

AR: I think there is a direct correlation<br />

between the second-rate teaching<br />

of history in schools and the<br />

thirst for historical knowledge that<br />

people have by the time they leave<br />

full-time education. It is a sad reflection<br />

that I am probably making a living<br />

out of the collapse of history<br />

teaching in primary and secondary<br />

and, to a large extent, tertiary education.<br />

But there we are. I am and so<br />

are an awful lot of other people. I<br />

think that history ought to be taught<br />

in narrative terms; I think it ought to<br />

be taught chronologically; I think<br />

that the older a child gets the further<br />

down the story he ought to be<br />

brought. So the Tudors and Stuarts<br />

are ideal for children at the age of<br />

thirteen and fourteen and the Second<br />

World War and the First World War<br />

shouldn’t be really taught until the<br />

children are just about to take their<br />

final leaving exams. And when children<br />

are at primary school, then wattle-and-daub<br />

houses and motte-andbailey<br />

castles are ideal, too. I really<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 5

Andrew Roberts<br />

do think that unless you see history<br />

in its full chronological narrative<br />

sense you can’t really appreciate it. I<br />

hate the way that first of all schoolchildren<br />

are constantly taught the<br />

Nazis again and again when it hasn’t<br />

been put into proper historical perspective.<br />

There is an amazing gold-<br />

“ Tony Blair basically believes that<br />

history began on the morning of the<br />

2nd May 1997 ”<br />

en age of history writing at the<br />

moment. This has to be related in<br />

some way to the collapse of history<br />

teaching in our education system.<br />

Having said that, I am not sure that<br />

it is not just going to be a fad. It has<br />

been around for only five or six or<br />

seven years and all it would take, I<br />

think, would be for some big and<br />

powerful people in the BBC and various<br />

other places to say: “Right,<br />

that’s enough history. Let’s now<br />

move on to science.” Or “We ought<br />

to be concentrating now on some<br />

other area of human endeavour.” for<br />

the tap to be turned off. Obviously,<br />

that can’t be done in book publishing<br />

but it certainly can be in the TV<br />

world. And so, all that we can do is<br />

to keep our fingers crossed that really<br />

talented historians who can make<br />

first-class TV series, like Simon<br />

Schama, David Starkey and Niall<br />

Ferguson, should continue to do so,<br />

“ Society is a combination of the<br />

living, the dead and those yet to be<br />

born. And so history is a part of<br />

society’s present day existence as<br />

much as that of the past ”<br />

because I think there is a huge<br />

knock-on effect for people who will<br />

watch, say, Niall’s programmes on<br />

empire, will then take one of the<br />

fifty or so ideas that come from it<br />

and look more closely into them and<br />

buy books on some of them. That<br />

has to be a good thing, especially as<br />

6 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

I am convinced that there is an<br />

external as well as an internal threat<br />

to British understanding of British<br />

history. It’s constantly being debellicised.<br />

The kind of propaganda that<br />

we keep getting out of the European<br />

Union, and some of our newspapers<br />

are very good at spotting this, others<br />

aren’t, constantly tries to make<br />

Britain out to be yet another<br />

European country that does not have<br />

a completely unique historical background.<br />

And that’s tremendously<br />

dangerous because after a generation<br />

of being taught this a new generation<br />

of schoolchildren will come to maturity<br />

and voting age believing it. And<br />

if they do, that will not only betray<br />

them because that is untrue - Britain<br />

does have a history unlike any other<br />

nation - but it is also going to let the<br />

country down.<br />

HS: I think one of the sad things about<br />

the study of history is that one is endlessly<br />

asked - I am sure you were<br />

when you first started studying it and<br />

I remember it - why does one want to<br />

study it. It’s just lots of stories about<br />

dead people. What does it matter? A<br />

particularly dangerous part of that is<br />

that politicians are very apt to say<br />

this. Now, one might say who cares<br />

what politicians have to say but they<br />

do have a lot of power.<br />

AR: Well, Charles Clarke has, of<br />

course, spoken against the teaching<br />

of mediaeval history.<br />

HS: Indeed back in the sixties, I think<br />

it was Edward Short, who was<br />

Education Secretary under Wilson,<br />

who said that it was more important<br />

for children to know about the<br />

Vietnam War, which was still going<br />

on at the time than about the Wars of<br />

the Roses. So the rot set in, perhaps,<br />

with that government.<br />

AR: And also, of course, Tony Blair<br />

basically believes that history began<br />

on the morning of the 2nd May 1997.<br />

HS: Yes, that is an extremely unfortunate<br />

part of it all. Now if a Minister of<br />

Education from a forthcoming<br />

Conservative government, as it is<br />

unlikely to be a Tory government,<br />

came to you and said: “Why do you<br />

think we should concentrate on teaching<br />

history at school?”, what would<br />

you answer?<br />

AR: I would say: “Why do you think<br />

it is important for your brain to have<br />

a memory?” And I would also argue<br />

to those - and this is a truly Tory<br />

argument, one that Burke would<br />

have appreciated: I would say that<br />

why should experiences of the living<br />

be given any superiroity over those<br />

of the dead? Society is a combination<br />

of the living, the dead and those<br />

yet to be born. And so history is a<br />

part of society’s present day existence<br />

as much as that of the past.<br />

Especially in a country like this one.<br />

Tony Blair says we’re a new country.<br />

No, we’re not! Of course we’re not a<br />

new country. You walk out into any<br />

street and you will immediately see<br />

that we are not a new country. We<br />

are not Arizona. It is completely<br />

absurd to argue that we are because<br />

every step we take reminds us that<br />

we are not. And the other thing, of<br />

course, is that we never learn from<br />

history. You look again and again at<br />

problems and the way in which the<br />

world tries to deal with them is pretty<br />

much the way it has done in the<br />

past. The same problems, in fact,<br />

that face Tony Blair at the moment<br />

in terms of House of Lords reform,<br />

devolution, the Balkans, faced Lord<br />

Rosebery. And, don’t think that Mr<br />

Blair’s answers to them are any more<br />

well-informed or likely to be successful<br />

than were Rosebery’s. If we<br />

didn’t know what had been done in<br />

the past, we would be like the chap<br />

who wakes up every morning in the<br />

movie Memento. He’d lost his memory<br />

and he wakes up every morning<br />

and remembers nothing and has to<br />

find his way forward from snapshots<br />

he had taken. That would be what we<br />

would be like if a future minister<br />

tries to axe history even more than it<br />

has been deleted already from the<br />

national curriculum.<br />

HS: Andrew, thank you very much.

THATCHER<br />

Her legacy for the Conservatives and for Britain<br />

25 years on from Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 general election victory the Conservative History Journal examines her<br />

legacy. In this first article Norman Tebbit and Geoffrey Howe offer their different perspectives on her premiership;<br />

in further articles Nicholas Hillman examines the Iron Lady’s surprising influence on the world of pop music and<br />

Helen Szamuely reflects on the speeches of one of the twentieth century’s finest orators.<br />

Norman Tebbit was a close ally of<br />

Margaret Thatcher both in opposition<br />

and in government. He served as her<br />

Secretary of State for Employment,<br />

Secretary of State for Trade and<br />

Industry and President of the Board<br />

of Trade. Between 1985 and 1987 he<br />

was Chancellor of the Duchy of<br />

Lancaster and Party Chairman. As<br />

the latter, he was credited with the<br />

strategy behind the third<br />

Conservative electoral victory.<br />

During the Brighton hotel bombing<br />

Norman Tebbit was seriously injured<br />

and his wife, Margaret, permanently<br />

disabled. He retired from the House<br />

of Commons in 1992 and became<br />

Baron Tebbit of Chingford. Here he<br />

gives his perspective on the Thatcher<br />

government.<br />

Norman Tebbit<br />

recieves a standing<br />

ovation after his<br />

speech to the<br />

Conservative Party<br />

Conference in<br />

1981. Margaret<br />

Thatcher and Cecil<br />

Parkinson join in<br />

the applause.<br />

Margaret Thatcher<br />

took office as<br />

Prime Minister of a<br />

country possessed<br />

by both hope and<br />

fear. The Heath government had been<br />

defeated following its failure to<br />

defeat a miners’ strike in 1974. The<br />

Callaghan government fell in 1979 ,<br />

following the “winter of discontent”<br />

during the strike of local government<br />

workers. Many voters hoped she<br />

would go the same way. Rather more<br />

hoped she would not - but many even<br />

of these feared that she might.<br />

Foreign embassies were reporting<br />

to their governments that Britain had<br />

become ungovernable. Multi-national<br />

companies had all but ceased to<br />

invest as the English Disease, a lemming-like<br />

propensity to strike, savaged<br />

businesses. The vast stateowned<br />

sector of industry gorged<br />

itself on taxpayers’ money with no<br />

prospects of profitability.<br />

Inflation was endemic and conventional<br />

wisdom held that it could be<br />

restrained only by a state sponsored<br />

“prices and incomes policy”, that is<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 7

Thatcher<br />

either voluntary or state control of<br />

prices and incomes.<br />

During Margaret Thatcher’s term<br />

British industrial relations changed<br />

from the worst in the developed free<br />

world to the best.<br />

She went on to win two further elections,<br />

defeated the unions’ “nuclear<br />

option” of a miners’ strike, and was<br />

brought down not by an ungovernable<br />

nation - but an ungovernable cabinet.<br />

In the meantime inflation had been<br />

controlled by monetarism - not<br />

incomes policy - and foreign ivestment<br />

had poured into Britain. The<br />

financial haemorrhage of the nationalised<br />

industries had been stanched.<br />

After privatisation they became profitable<br />

corporation taxpayers.<br />

Living standards soared, millions<br />

Geoffrey Howe was Margaret<br />

Thatcher’s longest standing Cabinet<br />

minister, serving as Chancellor of the<br />

Exchequer, Secretary of State for<br />

Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs<br />

and Leader of the House of<br />

Commons. He resigned on November<br />

1, 1990 with a thunderous speech in<br />

8 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

of the “working classes” had become<br />

homeowners and shareholders and<br />

Britain’s occupational pension<br />

schemes were the envy of Europe.<br />

In passing Margaret Thatcher<br />

defeated Argentina, bringing down<br />

the junta and by a military operation<br />

“ Living standards soared, millions of<br />

the “working classes” had become<br />

homeownders and shareholders ”<br />

pursued with purpose, skill and daring,<br />

established that Britain still had<br />

the will and power to defend unilaterally<br />

its people and its interest.<br />

She left a great deal still undone,<br />

having had neither time - nor enough<br />

the House of Commons that is widely<br />

thought to have hastened Thatcher’s<br />

own downfall three weeks later.<br />

Geoffrey Howe retired from the<br />

House of Commons in 1992 and<br />

became Baron Howe of Aberavon.<br />

Here he gives his views of the<br />

Thatcher government.<br />

competent Ministers with courage to<br />

resolve other issues. Neither education,<br />

the Health Service, nor the welfare<br />

system were properly reformed.<br />

Local government finance reform<br />

was botched by Christopher Patten.<br />

Reform of the European Community<br />

was sabotaged by Geoffrey Howe.<br />

Nor did Thatcherism cure the sickness<br />

of the permissive society, which<br />

has - as some forecast - become the<br />

yob society of the 21st century.<br />

Abroad Margaret Thatcher stiffened<br />

the resolve of President Reagan<br />

to defeat the challenge of the Soviet<br />

Union and bring a decisive victory in<br />

the Cold War. “Thatcherism” was<br />

widely adopted throughout the world.<br />

So much achieved - so much more<br />

to be done.<br />

No government, in my<br />

judgment, did more in<br />

the last quarter of the<br />

twentieth century to<br />

change the shape of<br />

our world. Some mistakes, of course<br />

- but overall it was fundamental and<br />

enduring change for the better.<br />

Margaret Thatcher’s most important<br />

domestic achievement was the dismantling<br />

of the unspoken, but crippling,<br />

compact between state ownership and<br />

monopoly trade unionism. Almost as<br />

crucial was the recovery of control over<br />

the public finances and the key switch<br />

of Britain’s tax structure away from on<br />

“ The one sadness is that Michael<br />

Heseltine might have done better still ”<br />

Margeret Thatcher<br />

and Foreign<br />

Secretary Geoffrey<br />

cross the tarmac at<br />

Heathrow on the<br />

way to the Stuttgart<br />

Summit in 1983.<br />

Press Secretary<br />

Bernard Ingham<br />

and Cabinet<br />

Secretary Robin<br />

Butler look on.<br />

which positively obstructed enterprise.<br />

The real triumph was to have<br />

transformed not just one party but<br />

two - so that when Labour did finally<br />

return, these changes were accepted<br />

as irreversible. The irony is that<br />

Thatcherism might never have survived<br />

at all, had it not been for John<br />

Major’s success in consolidating it.<br />

The one sadness is that Michael<br />

Heseltine might have done better<br />

still, by securing as well the<br />

European role for Britain, which Ted<br />

Heath had made possible.

Hilda’s<br />

cabinet<br />

inspired by<br />

Margaret Thatcher<br />

Nicholas<br />

bandSongs<br />

Hillman<br />

Nicholas Hillman worked for David<br />

Willetts between 1999 and 2003. He<br />

has written for the Journal of<br />

Contemporary History, Searchlight<br />

and the Birmingham Post as well as<br />

It is often assumed that pop<br />

music was depoliticised in<br />

the 1980s. The theory goes<br />

that once punk had flowed its<br />

full course, then politics and<br />

pop music disassociated themselves<br />

from one another. One journalist, for<br />

example, recently claimed that<br />

Ghost Town, the 1981 Number 1 single<br />

by The Specials - a ska band who<br />

emerged out of punk - marked the<br />

final moment when popular culture<br />

and politics came together ‘as one’.<br />

But, while some of the general<br />

political heat might have dissipated<br />

out of the music scene during the<br />

1980s, there was one subject that<br />

could still tempt even the most indolent<br />

songwriters to put pen to paper:<br />

Margaret Thatcher.<br />

Many of the songs inspired by<br />

Mrs Thatcher and her breed of<br />

Conservatism are undeniably puerile<br />

and naïve and some are also remarkably<br />

unmemorable. The chance of<br />

them having any measurable impact<br />

on British politics was always going<br />

to be remote. But Conservative supporters<br />

nonetheless have to recog-<br />

a number of think-tanks. Here he<br />

analyzes the impact Margaret<br />

Thatcher’s personality and political<br />

achievements had on the pop songs<br />

of the period.<br />

nise that the devil does have all the<br />

best tunes.<br />

Stand Down Margaret<br />

It is not particularly easy to categorise<br />

the songs for which Margaret<br />

Thatcher was the primary target. But<br />

one recurring theme was a simple<br />

desire to see her leave office.<br />

The Beat’s Stand Down Margaret,<br />

which reached Number 22 in the<br />

charts in 1980, is an early example.<br />

Simply Red expressed the same sen-<br />

“ It is not particularly easy to<br />

categorise the songs for which Margaret<br />

Thatcher was the primary target. But<br />

one recurring theme was a simple<br />

desire to see her leave office ”<br />

timent in their song She’ll Have to<br />

Go from the 1989 album A New<br />

Flame. The avowedly political - and<br />

now Blairite - lead singer, Mick<br />

Hucknall sang in the chorus:<br />

‘Breaking our backs with slurs, And<br />

taking our tax for murdering, The<br />

only thing I know, She’ll have to<br />

go’.<br />

Not surprisingly, given the title,<br />

many of the songs on She Was Only<br />

a Grocer’s Daughter, the second<br />

album by The Blow Monkeys, were<br />

inspired by Thatcherism. One of the<br />

singles from the album, the luxuriant<br />

(Celebrate) The Day After You<br />

focussed on the time when Mrs<br />

Thatcher would no longer be Prime<br />

Minister. The song was only in the<br />

charts for two weeks and peaked at<br />

Number 52 - forty-seven places<br />

lower than an earlier politicallymotivated<br />

single from the same<br />

album. This relative failure appears<br />

to have been partly due to the concerns<br />

of broadcasters, such as the<br />

BBC, who were reluctant to play<br />

such an explicitly political song in<br />

the run-up to the 1987 General<br />

Election.<br />

Margaret on the Guillotine<br />

For other artists, it was not enough<br />

simply to wish Mrs Thatcher out of<br />

office. Elvis Costello, who would<br />

sometimes play Stand Down<br />

Margaret in his sets, expressed even<br />

harsher sentiments in Tramp the Dirt<br />

Down on his 1989 album Spike. The<br />

song begins with an image of Mrs<br />

Thatcher kissing a crying child in a<br />

hospital and continues with Costello<br />

hoping that he will live long enough<br />

to taunt the Prime Minister even<br />

after her death. When playing the<br />

song live in later years, Costello<br />

sometimes introduced it with a<br />

quick burst of Ding Dong the Witch<br />

is Dead from The Wizard of Oz and<br />

added a verse about John Major.<br />

Margaret on the Guillotine was<br />

included as the final track on Viva<br />

Hate, the first solo album by<br />

Morrissey, previously lead singer of<br />

The Smiths. The song had originally<br />

been intended as the title track of<br />

what became the seminal 1986<br />

album The Queen is Dead and, when<br />

it finally saw the light of day in<br />

1988, Morrissey was interviewed by<br />

the police because the lyrics were<br />

regarded as menacing. While the<br />

music for Margaret on the<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 9

Hilda’s cabinet band<br />

Guillotine lacks the power of many<br />

of Morrissey’s other songs, the<br />

lyrics contain an unmistakeably vitriolic<br />

anger. The same is true of the<br />

only chart entry by the band<br />

“ No assessment of modern British<br />

political song-writing is complete without<br />

some mention of Billy Bragg ”<br />

S*M*A*S*H. Their 1994 single I<br />

Want to Kill Somebody, which<br />

reached Number 26, is also notable<br />

for finding something to rhyme with<br />

Virginia Bottomley and for the<br />

band’s incomplete grasp of spelling<br />

and grammar: ‘Whoever’s in power,<br />

I’ll be the opposition, I want to kill<br />

somebody, Margaret thatcher,<br />

Jefferey archer, Michael heseltine,<br />

John Major, Virginia Bottomeley<br />

especially’ (sic).<br />

Shipbuilding<br />

Another theme popular among<br />

musicians opposed to Thatcher was<br />

the Falklands War. Elvis Costello<br />

wrote the lyrics to Shipbuilding for<br />

Below: Stephen<br />

Patrick Morrissey.<br />

in his album Viva<br />

Hate, the former<br />

Smiths frontman<br />

wanted to see<br />

‘Margaret on the<br />

Guillotine’.<br />

10 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

Robert Wyatt, formerly of Soft<br />

Machine, after reading about the war<br />

in the Australian press, and the song<br />

was a minor hit in 1983. Less direct<br />

than many anti-Thatcher tracks, the<br />

song cleverly contrasts the additional<br />

employment from new shipbuilding<br />

with the use of the ships in war -<br />

the words lament that ‘Within weeks<br />

they’ll be re-opening the shipyard,<br />

And notifying the next of kin once<br />

again, It’s all we’re skilled in, We<br />

will be shipbuilding’. The song is<br />

perhaps the most enduring and influential<br />

of all anti-Thatcher songs; it<br />

was also recorded by Costello himself,<br />

Tasmin Archer, who issued it as<br />

a single in the first half of the 1990s,<br />

and Suede.<br />

Other songs that refer to the<br />

Falklands conflict range from the<br />

ironic Happy Days by The Shamen,<br />

to the strange War by The Rugburns:<br />

‘The Falklands was cool but it was<br />

too damn short, I want a real war<br />

cause I built a bitchin fort’. The dour<br />

Mentioned in Dispatches by<br />

Television Personalities and the<br />

Faith Brothers’ Easter Parade were<br />

more direct in their criticism. The<br />

latter tells of a 19 year old who is<br />

injured in battle: ‘My mind<br />

ingrained, I came home maimed, So<br />

was kept away from the Easter<br />

Parade. … The mother of the nation<br />

cries “Rejoice”, And I can hardly<br />

shuffle, Struck down for what the<br />

mean can do for political ambition’.<br />

Mother knows best<br />

No assessment of modern British<br />

political song-writing is complete<br />

without some mention of Billy<br />

Bragg. Along with Paul Weller of<br />

The Style Council, he led the<br />

Labour-supporting Red Wedge in<br />

the mid-1980s and his songs cover<br />

topics as diverse as the recent Iraq<br />

war (The Price of Oil), the inter-war<br />

slump (Between the Wars) and rightwing<br />

newspapers (It Says Here); in<br />

1990, his manager, Peter Jenner, was<br />

reported to have said, ‘If you have a<br />

good, right on cause, don’t ask Billy<br />

to play a benefit for it because you’ll<br />

lose.’ Bragg’s song Thatcherites lays<br />

wide-ranging criticism on top of the<br />

tune to a much earlier political song<br />

Ye Jacobites By Name: ‘You privatise<br />

away what is ours, what is ours,<br />

You privatise away what is ours, You<br />

privatise away and then you make us

pay, We’ll take it back someday,<br />

mark my words, mark my words,<br />

We’ll take it back some day mark my<br />

words’.<br />

Other prominent folk singers also<br />

produced broad critiques of<br />

Thatcherism. Lal Waterson’s Hilda’s<br />

Cabinet Band is perhaps the cleverest<br />

anti-Thatcher song of all. The<br />

Cabinet is portrayed as a band who<br />

are leading a dance and the lyrics<br />

invert the traditional instructions of<br />

band leaders. Recalling ‘the lady’s<br />

not for turning’, the song starts with<br />

‘the one where you never turn<br />

around’ and continues with the command<br />

to ‘Put your right boot in, put<br />

it in again, Poll tax your girl in the<br />

middle of the ring, Privatise your<br />

partner, do it on your own, Kick the<br />

smallest one among you, promenade<br />

home’.<br />

Richard Thompson, originally of<br />

Fairport Convention, played at one<br />

time with Lal Waterson’s band, The<br />

Watersons, and he penned his own<br />

anti-Thatcher song, Mother Knows<br />

Best. Lyrically, it, too, is a step<br />

above many other comparable songs.<br />

But it seeks to challenge<br />

Thatcherism head-on at its strongest<br />

point - the championing of freedom<br />

and the retreat of the nanny state -<br />

and many of the lyrics are ultimately<br />

unpersuasive: ‘So you think you<br />

know how to wipe your nose, So you<br />

think you know how to button your<br />

clothes, You don’t know shit, If you<br />

hadn’t already guessed, You’re just a<br />

bump on the log of life, Cos mother<br />

knows best’.<br />

God Save the Queen<br />

Some Conservatives would no doubt<br />

consider many of the songs targeted<br />

at Mrs Thatcher to be highly offensive,<br />

but she was not too concerned<br />

about them. When, in the run-up to<br />

the 1987 General Election, Mrs<br />

Thatcher was asked by Smash Hits,<br />

the leading pop music magazine of<br />

the day, what she thought of leftwing<br />

pop stars ‘who can’t wait to get<br />

you out of Number 10’, she replied:<br />

‘Can’t they? Ha ha ha! … most<br />

young people rebel and then gradually<br />

become more realistic. It’s very<br />

much part of life, really. And when<br />

they want to get Mrs Thatcher out of<br />

Number 10 - I’ve usually not met<br />

most of them. … it’s nice they know<br />

your name.’<br />

Besides, Mrs Thatcher is in very<br />

good company. The Queen is also<br />

“ Some Conservatives would no<br />

doubt consider many of the songs<br />

targeted at Mrs Thatcher to be highly<br />

offensive, but she was not too<br />

concerned about them ”<br />

the target of a number of powerful<br />

songs, such as God Save the Queen<br />

by The Sex Pistols and the aforementioned<br />

The Queen is Dead, as<br />

well as Elizabeth My Dear, a 59-second<br />

pastiche of Scarborough Fair on<br />

The Stone Roses’ debut album (‘My<br />

aim is true, my purpose is clear, It’s<br />

curtains for you Elizabeth my dear’).<br />

If anything, these songs are more<br />

effective than those targeted at Mrs<br />

Thatcher, yet they have done next to<br />

nothing to popularise republicanism.<br />

Tony Blair is also the subject of<br />

some critical songs, despite New<br />

Labour’s promotion of Cool<br />

Britannia. In You and Whose Army,<br />

Radiohead challenge the Prime<br />

“ Tony Blair is also the subject of some<br />

critical songs, despite New Labour’s<br />

promotion of Cool Britannia. In You and<br />

Whose Army, Radiohead challenge the<br />

Prime Minister to a fight ”<br />

Minister to a fight. And in the much<br />

cleverer Cocaine Socialism, Pulp’s<br />

lead singer Jarvis Cocker derides the<br />

Labour Party for the desperate<br />

nature of their campaign to win support<br />

from celebrities. His mother,<br />

who - like Madonna’s mother-in-law<br />

- is a Conservative activist, unsurprisingly<br />

approved of the song.<br />

Girl Power<br />

Moreover, the pop music scene as a<br />

Hilda’s cabinet band<br />

whole is somewhat less antagonistic<br />

to Thatcherism than this review<br />

might suggest. The influential<br />

Happy Mondays are supposed to<br />

have said that Mrs Thatcher was<br />

‘alright. She’s a heavy dude.’ Prior<br />

to the 1997 General Election, two of<br />

the five members of the most successful<br />

band of the day, The Spice<br />

Girls, spoke highly of Mrs Thatcher<br />

in an interview in The Spectator.<br />

Geri Halliwell, aka Ginger Spice,<br />

said, ‘We Spice Girls are true<br />

Thatcherites. Thatcher was the first<br />

Spice Girl, the pioneer of our ideology<br />

- Girl Power.’<br />

Ten years earlier, Smash Hits had<br />

asked a number of pop stars which<br />

way they intended to vote in the<br />

forthcoming General Election. Only<br />

one said he would be voting<br />

Conservative - Gary Numan bravely<br />

confirmed his support for Mrs<br />

Thatcher, even though it had already<br />

seriously damaged his credibility<br />

among the music press. But the article<br />

also showed that, even if the vast<br />

majority of 1980s pop stars were not<br />

inclined towards Thatcherism, they<br />

were not overwhelmingly supportive<br />

of the Labour Party either. Despite<br />

the supposed credibility of initiatives<br />

such as Red Wedge, fewer than<br />

half of the 14 stars interviewed said<br />

they would definitely vote Labour<br />

and most of the six that did were<br />

already known to be outspoken on<br />

political issues. The article even<br />

pours doubt on the claim that is<br />

often made by journalists that<br />

George Michael was a ‘lifelong<br />

Labour voter until 2001’ for he told<br />

the magazine ‘I’ll probably vote for<br />

the SDP/Liberal Alliance’.<br />

Most significantly of all, the various<br />

anti-Thatcher songs are not the<br />

only evidence that pop music continued<br />

to reflect political culture<br />

during the 1980s. It is sometimes<br />

forgotten that many of the most successful<br />

bands of the decade, such as<br />

Duran Duran with their slick videos<br />

and ostentatious wealth, summed up<br />

the economic boom just as effectively<br />

as the protest songs encapsulated<br />

the more negative aspects of<br />

Thatcherism.<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 11

A strangely familiar voice<br />

Helen Szamuely<br />

There is nothing like hearing<br />

speeches by a politician to bring<br />

back memories and to evolve<br />

comparisons with the present<br />

day. Helen Szamuely, co-editor<br />

of the Conservative History<br />

Journal listens to the 3 CDs produced<br />

by Politico's of Margaret<br />

Thatcher's great speeches.<br />

Not long ago I was<br />

telling a young<br />

American, who<br />

works at one of the<br />

many think-tanks in<br />

Washington DC, that there was<br />

something about Margaret<br />

Thatcher that made all the men<br />

who had worked with her or just<br />

met her go weak at the knees.<br />

"Well," - he said rather sheepishly,<br />

- "funny you should say that. I<br />

met her at a dinner last week and<br />

thought she was amazing." Not<br />

for the first time I wondered how<br />

the Lady managed to captivate<br />

every male that came into her<br />

orbit. Listening to the speeches<br />

systematically I began to understand<br />

a little.<br />

Two of the CDs chart<br />

Thatcher's career from the first<br />

interview for ITN, given immediately<br />

after her maiden speech<br />

in February 1960. She sounds<br />

hesitant and rather prissy. Her<br />

slightly high, girlish gush<br />

would have been enough to<br />

irritate anyone. By the time of<br />

the second interview on her<br />

first day as Parliamentary<br />

Secretary to the Ministry of<br />

Pensions, in October 1961, the<br />

gushing is less obvious, but<br />

there is still that high-pitched<br />

tone, that girlish breathlessness.<br />

Both disappear very<br />

quickly as Margaret Thatcher<br />

rises to become a force in the<br />

Conservative Party.<br />

We plunge into a rapid trip<br />

through the years that came to be<br />

dominated by this extraordinary<br />

political figure: her tussles with<br />

the teachers' unions, her election<br />

as leader of the party, that fateful<br />

election of 1979; and the years<br />

of the premiership: the fights<br />

with the unions and with inflation,<br />

with the Labour Party and<br />

her own so-called supporters, the<br />

fraught and finally glorious days<br />

of the Falklands War, the fight<br />

against the Communist enemy<br />

and its sympathizers at home;<br />

the lows of her political career:<br />

the Westland affair, the terrible<br />

Brighton bomb and, finally, the<br />

last struggle over Europe and the<br />

defeat at the hands of her own<br />

party. There are other speeches<br />

of her political life after<br />

November 22, 1990 but it is all a<br />

sad coda to a glittering career.<br />

The third CD (a bonus, as it is<br />

described by the publisher) gives<br />

full versions of a couple of<br />

speeches, a specially produced<br />

sketch from Yes Prime Minister,<br />

in which Thatcher demands the<br />

abolition of economists on the<br />

grounds that they just fill politicians'<br />

heads with ridiculous<br />

notions, and a couple of other<br />

curios.<br />

Listening to the speeches one is<br />

reminded of all the famous<br />

occasions and phrases: the<br />

Iron Lady of the Western<br />

World, the Lady is not<br />

for turning, the<br />

famous No! No! No!<br />

to the back door<br />

socialism of Delors's<br />

plans, the Labour<br />

Chancellor being<br />

12 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

"frit" and many others. But there<br />

is something else there. Well, two<br />

other things, to be precise.<br />

One is Thatcher's ability to<br />

adapt her speech to whatever<br />

goes on in the audience, whether<br />

it is friendly laughter or<br />

unfriendly heckling. As time<br />

went on she got better at it, as<br />

did many politicians of the older<br />

generation. She was, perhaps,<br />

better than most in the way she<br />

almost flirted with her audience,<br />

with the journalists, the cameramen.<br />

I cannot help remembering<br />

Thatcher's visit to the then<br />

Soviet Union and the long TV<br />

inteview she gave. Facing<br />

numerous journalists she<br />

answered them firmly and<br />

severely but with just a hint of<br />

flirtatiousness, finding the questions<br />

they thought very daring,<br />

extremely easy to handle. By the<br />

end of the hour she had them eating<br />

out of her hand. The rest of<br />

the country was swooning as<br />

well. When I went to Moscow a<br />

few weeks after her visit, I heard<br />

nothing but<br />

accounts of<br />

Thatcher's clothes, Thatcher's<br />

interview, what Thatcher said<br />

and where Thatcher went.<br />

There is something else in<br />

those speeches: the constant<br />

theme of liberty and patriotism.<br />

Somehow, one forgets how often<br />

she spoke passionately of freedom<br />

and its importance for<br />

everyone, whether in Britain or<br />

other countries. Listening<br />

through the speeches, one after<br />

another, I was struck by the fact<br />

that she had, with some deviation<br />

and hesitation in her actions,<br />

kept faith with that early<br />

announcement that what she<br />

believed in was liberty.<br />

A few weeks ago I saw Lady<br />

Thatcher in the House of Lords.<br />

She came out of the Chamber<br />

and went through Peers' Lobby<br />

chatting to somebody. I am a<br />

strong, though not uncritical<br />

admirer of the Lady, but I was<br />

amazed to see that every head<br />

turned to watch her go. "What do<br />

you expect?" - said my companion.<br />

- "There has been no other<br />

politician since her time."<br />

Margaret Thatcher - The Great<br />

Speeches, 3 CDs, £19.99,<br />

published by Politico’s<br />

Media and available from<br />

www.politicos.co.uk

The political demise of<br />

Neville<br />

Chamberlain<br />

Harshan Kumarasingham<br />

Harshan Kumarasingham is a PhD<br />

student in Political History at<br />

Victoria University of Wellington,<br />

New Zealand. He has recently competed<br />

an MA thesis, entitled "For the<br />

Good of the Party - An Analysis of the<br />

Fall of British Conservative Party<br />

Leaders from Chamberlain to<br />

Thatcher". Here he looks at the<br />

events that led to the end of Neville<br />

Chamberlain's government and political<br />

career in 1940.<br />

Chamberlain<br />

boards an aircraft<br />

bound for Munich<br />

to have talks with<br />

Adolf Hitler, over<br />

the future of the<br />

disputed Czech<br />

Sudetenland, 1938.<br />

As the Prime Minister<br />

drove through the hallowed<br />

avenue to<br />

Buckingham Palace he<br />

was rapturously welcomed<br />

by streets 'lined from one end<br />

to the other with people of every class,<br />

shouting themselves hoarse, leaping<br />

on the running board, banging on the<br />

windows, and thrusting their hands<br />

into the car to be shaken'. ’ The reader<br />

would be forgiven to believe that<br />

these were the words describing<br />

Winston Churchill at the end of the<br />

Second World War about to present<br />

himself to the exuberant multitudes<br />

that awaited him to celebrate victory<br />

in Europe in May 1945. In fact these<br />

were the words depicting Neville<br />

Chamberlain as he returned from<br />

Munich, infamously, with that little<br />

piece of paper that he assumed triumphantly,<br />

and in the end tragically,<br />

would mean 'peace in our time'<br />

The sixty-eight year old<br />

Chamberlain had been the "natural<br />

choice" to succeed the lethargic<br />

Stanley Baldwin and become Prime<br />

Minister and leader in 1937, his leadership<br />

seconded by no less a person<br />

than Winston Churchill. The second<br />

son of the great Joseph Chamberlain<br />

had a keen administrative talent that<br />

had been proven through his effective<br />

tenure at the Health Ministry and his<br />

financial acumen had enabled him to<br />

show a steady and businesslike competence<br />

when at the Exchequer during<br />

the Great Depression era.<br />

Yet for all his domestic competence,<br />

his years of patient and prudent<br />

financial and social policy, his reliable<br />

Conservative statecraft, it is one policy<br />

that is forever entwined with his<br />

name - appeasement. This would initially<br />

earn the applause of<br />

Conservatives but would eventually<br />

compel them to assent to<br />

Chamberlain's dramatic dethronement<br />

in 1940.<br />

History (and perhaps Winston<br />

Churchill) has often glorified<br />

Chamberlain's downfall as an event<br />

that corrected past mistakes and injustices.<br />

However, Chamberlain, just<br />

months before his resignation, was<br />

recording some of the highest<br />

Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong> | 13

Neville Chamberlain<br />

approval ratings in British political<br />

history and seemed to have silenced<br />

any opposition to his leadership. This<br />

enigmatic figure's leadership is too<br />

easily discarded by populist historical<br />

misunderstanding.<br />

Chamberlain had returned triumphant<br />

from Munich, as the saviour<br />

of peace, greeted by relieved and<br />

delirious crowds the size of which<br />

were not seen again till VE day. The<br />

pact vindicated appeasement and<br />

sealed the ascendance of Chamberlain<br />

over his detractors. The only isolated<br />

casualty was the meek resignation of<br />

Alfred Duff Cooper, who had no wish<br />

to bring down the Government. The<br />

majority shared the concerted sense of<br />

alleviation that war had been forestalled,<br />

which proved intoxicating for<br />

Chamberlain and his followers.<br />

Chamberlain had staked much on<br />

Munich as a populist method to contain<br />

his enemies at home as well as<br />

abroad. In the Cabinet the Prime<br />

Minister could rely upon Sir Samuel<br />

Hoare, Sir John Simon and Lord<br />

Halifax. These three most senior ministers,<br />

especially Hoare and Simon,<br />

would act as loyal Chamberlainites<br />

who buttressed and guarded their<br />

leader and with whom Chamberlain<br />

could compel the Cabinet towards his<br />

objectives. Subsequently, with their<br />

power entwined with Chamberlain's<br />

they would also share their leader's<br />

fate and for ever lose their centrality to<br />

power - Simon relegated to the wilderness<br />

of the Woolsack while Hoare and<br />

Halifax were effectively exiled as<br />

emissaries to Madrid and Washington<br />

respectively.<br />

But in 1938 their power was substantial<br />

and Munich had, albeit fleetingly,<br />

strengthened their hold on the<br />

reins. With the chorus of support for<br />

the Prime Minister, Conservative<br />

Central Office urged Chamberlain to<br />

dissolve Parliament and secure an<br />

increased majority under his leadership<br />

that was predicated to be on the<br />

scale of victories in 1931 and 1935. 2<br />

Indeed, when the Prime Minister<br />

entered the Commons for the Munich<br />

debate the entire Government benches<br />

rose in ovation for Chamberlain with<br />

five notable exceptions that included<br />

14 | Conservative History Journal | issue 3 | Summer <strong>2004</strong><br />

Duncan Sandys, Harold Nicolson and<br />

Churchill.<br />

The anti-appeasers, at this point,<br />

were more like a debating society and<br />

lacked cohesion and unity.<br />

Chamberlain, believing in his infallibility,<br />

was able with his popularity to<br />

deflate their most prominent member,<br />

the 'alarmist' Churchill. The normally<br />

stoic Prime Minister, to the lustrous<br />

amusement of the Treasury benches,<br />

mockingly exclaimed 'If I were asked<br />

whether judgement is the first of my<br />

Rt Hon. Friend's many admirable<br />

qualities I should ask the House of<br />

Commons not to press the point'. 3<br />

The threat to other potential rebel<br />

members was de-selection and a snap<br />

election on an issue that the majority<br />

of the public and Party supported.<br />

Rebel MPs faced reprimand not only<br />

from the Whips but, dispiritingly, from<br />

their own constituencies. In the<br />

Munich debate, with a majority of<br />

over two hundred, the abstention of<br />

twenty-two Conservatives was softly<br />

recorded. Writing to his sister,<br />

Chamberlain admitted the debate had<br />

been 'trying' and that he 'tried occasionally<br />

to take an antidote to the poison<br />

gas by reading a few of the countless<br />

letters & telegrams which continued<br />

to pour in expressing in moving<br />

accents the writer's heartfelt relief &<br />

gratitude. All the world seemed to full<br />

of my praises except the House of<br />

Commons'. 4 This exception would<br />

prove fatal.<br />

Chamberlain, taking the praise and<br />

plaudits from Britain and across the<br />