The Andrew Fuller Center Review – EDIT - Word of Truth

The Andrew Fuller Center Review – EDIT - Word of Truth

The Andrew Fuller Center Review – EDIT - Word of Truth

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

6 th Annual Conference <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies<br />

<br />

It is not every Baptist theologian who has a movement named after him, but<br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> was so important a theologian that historians <strong>of</strong> the church actually<br />

talk about a perspective called “<strong>Fuller</strong>ism.” <strong>Fuller</strong>’s views, though, were<br />

not the product <strong>of</strong> simply his own theological reflection, but were formulated<br />

by him in dialogue with a close circle <strong>of</strong> friends and subsequent joint action<br />

with these friends, especially in missionary endeavors. This year <strong>The</strong> <strong>Andrew</strong><br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies is thrilled to devote its annual conference to<br />

thinking about <strong>Fuller</strong>’s friends: their lives and ministries and how they shaped<br />

and were shaped by <strong>Fuller</strong>, whom later generations called “the elephant <strong>of</strong> Kettering”<strong>–</strong><br />

a reference to his weighty theological influence. Come and join us<br />

this September as we spend time and energy in thinking about a past Christian<br />

thinker and his circle <strong>of</strong> friends whose influence for good and for the Kingdom<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Lord Jesus has been enormous. <br />

<br />

Peter Beck, Nathan Finn, Grant Gordon, Michael A. G. Haykin, Sam Masters,<br />

Peter J. Morden, Kirk Wellum, J. Ryan West<br />

<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies<br />

Phone: (502) 897-4613 | Email: andrewfullercenter@sbts.edu<br />

Website: andrewfullercenter.org

e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

Issue 3 • Summer • 2012<br />

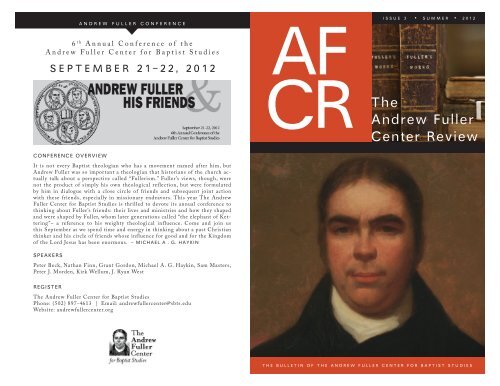

On the Cover:<br />

e oil portrait <strong>of</strong> <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> on the front cover <strong>of</strong> the review is<br />

by the painter Samuel Medley (1769-1857), the son <strong>of</strong> the famous<br />

Baptist minister, also Samuel Medley (1738-1799). e original oil<br />

painting is in the personal collection <strong>of</strong> Rev. Norman L. Hopkins <strong>of</strong><br />

Rochester, Kent, England. Rev. Hopkins is a long-standing, serious<br />

antiquarian book collector <strong>of</strong> Puritan and Baptist authors, who also<br />

purchases items <strong>of</strong> theological and historical interest. He saw noti cation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Fuller</strong> portrait for sale in an auction house in Northumbria<br />

in December, 2008, and recognized that it was clearly an authentic<br />

original portrait. He put in a bid well over the suggested price and was<br />

successful. Regretfully, the auctioneer was unwilling or unable to give<br />

him any details <strong>of</strong> the provenance <strong>of</strong> the painting beyond the fact that<br />

it was by Samuel Medley. e only other known oil painting <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> is<br />

in Regent’s Park College, the University <strong>of</strong> Oxford.<br />

e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Review</strong> is published 3 times per year by<br />

e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies.<br />

To Subscribe<br />

Subscription rates are US$30 (1 yr) for addresses in North America<br />

and US$35 for addresses outside North America (make your check or<br />

international money order payable to ‘ e Southern Baptist<br />

eological Seminary’).<br />

To subscribe, send your request to:<br />

e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies<br />

2825 Lexington Road<br />

Louisville, KY 40280<br />

Website: www.andrewfullercenter.org<br />

E-mail: andrewfullercenter@sbts.edu<br />

Editor Michael A.G. Haykin<br />

Managing Editor J. Ryan West<br />

Design and Layout Dustin Benge<br />

Fellows <strong>of</strong> e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Matthew Barrett<br />

Paul Brewster<br />

Je Robinson<br />

Jeongmo Yoo<br />

Junior Fellows <strong>of</strong> e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Dustin Benge<br />

Joe Harrod<br />

Cody McNutt<br />

Steve Weaver<br />

J. Ryan West<br />

and Baptists claimed to be “back to the Bible” movements, the view that created the<br />

greatest gulf between them was the Sandemanian view that salvation came through<br />

“bare belief in the bare gospel.” “Sandeman opposed any preaching that advocated<br />

any duty or activity that could be construed as merits <strong>of</strong> salvation on the part <strong>of</strong><br />

the individual” (p.72). is makes the study <strong>of</strong> Sandemanianism germane to anyone<br />

interested in the more recent gospel wars that have raged in the latter part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

twentieth century in American evangelicalism over the so-called “lordship salvation.”<br />

Many today seek to separate faith and repentance, believing that repentance is<br />

a de facto work. So a careful study <strong>of</strong> Sandemanianism and its decline may be useful<br />

in answering more recent similar objections.<br />

e student <strong>of</strong> Sandemanianism is further helped in Smith’s book by a comprehensive<br />

bibliography and a detailed index. In sum, Smith is to be thanked for bringing<br />

to life an obscure, now deceased sect, important in the study <strong>of</strong> Baptist history and<br />

evangelical theological debate, through this ne treatment.<br />

Je Straub, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Historical<br />

eology, Central Baptist eological Seminary, Plymouth, MN<br />

Roger D. Duke, Phil A. Newton, and Drew Harris, eds.<br />

and introduced, Venture All for God: Piety in the Writings<br />

<strong>of</strong> John Bunyan (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage<br />

Books, 2011), 194p.<br />

e richness and fullness <strong>of</strong> the piety <strong>of</strong> John Bunyan is<br />

o en obscured by the tremendous popularity <strong>of</strong> his greatest<br />

allegory, e Pilgrim’s Progress, and his famous autobiography,<br />

Grace Abounding to the Chief <strong>of</strong> Sinners. To be sure,<br />

these works must be included in any discussion <strong>of</strong> John Bunyan’s<br />

piety, but the discussion must not end here. In Venture<br />

All for God: Piety in the Writings <strong>of</strong> John Bunyan, the editors<br />

have selected a series <strong>of</strong> short readings taken from Bunyan’s lesser-known writings<br />

to present a more robust portrait <strong>of</strong> his piety. ese readings are arranged under<br />

the following headings: Christ Our Advocate, Christ Jesus the Merciful Savior, Hope<br />

for Sinners, True Humility, Christian Ethics, e Gospel Applied, and Warnings. A<br />

short, but surprisingly full biographical sketch <strong>of</strong> Bunyan’s life, ministry, and historical<br />

setting is also included. In addition to being a traveling pilgrim and an assured<br />

doubter, we see here that John Bunyan loved Christ deeply, exhorted sinners sincerely,<br />

and strove earnestly to live what he called a “gospelized” life.<br />

Bennett Rogers, PhD student,<br />

e Southern Baptist eological Seminary, Louisville, KY

John Howard Smith, e Perfect Rule <strong>of</strong> the Christian<br />

Religion: A History <strong>of</strong> Sandemanianism in the Eighteenth<br />

Century. Albany, New York: State University <strong>of</strong> New York<br />

Press, 2008. ix+ 236 pages<br />

Historians <strong>of</strong> the Baptist tradition encounter a number <strong>of</strong><br />

lesser known sects that intersect Baptist life down through<br />

the four centuries <strong>of</strong> our existence. ese secondary groups<br />

are important areas for expanded study as we seek to understand<br />

the Baptist theological battles in their context. Some<br />

<strong>of</strong> these movements were quite small and isolated, fading as<br />

quickly as they arose, yet they le a lasting impact on Baptist<br />

theology because <strong>of</strong> those who argued against them.<br />

One such movement is Sandemanianism or the Glasite movement that arose in<br />

Scotland through the in uence <strong>of</strong> John Glas (1695<strong>–</strong>1773). It was transplanted to<br />

North America by his better known son-in-law, Robert Sandeman (1714<strong>–</strong>1771).<br />

While its impact was on the fringes <strong>of</strong> Baptist life, its in uence was felt among some<br />

<strong>of</strong> our most recognizable names. Christmas Evans, the tireless Welsh Baptist evangelist,<br />

spoke <strong>of</strong> the Sandemanian in uence in Wales and its chilling e ect on his<br />

own spiritual journey. Among the Baptist worthies that contended with the teachings<br />

<strong>of</strong> Glas and Sandeman were the eminent British Baptist <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> (Strictures<br />

Against Sandemanianism) and the equally distinguished Isaac Backus (True Faith will<br />

Produce Good Works).<br />

Yet the student <strong>of</strong> eighteenth-century Baptist life up until now has been hard<br />

pressed to nd su cient material to study Sandemanianism in depth. John Howard<br />

Smith has recti ed this neglect with a carefully-researched and well-written history<br />

<strong>of</strong> this movement, focusing for the most part on its American connections but giving<br />

signi cant detail to satisfy the most curious among us <strong>of</strong> this now distant sect, its<br />

origins and its impact.<br />

e story begins with John Glas’ break with Scottish Presbyterianism in October <strong>of</strong><br />

1727 and takes the reader on a journey through the developing chronicle <strong>of</strong> how the<br />

Glasites, via Robert Sandeman, came to nd a more welcoming environment for the<br />

propagation <strong>of</strong> their particular theology in North America. Along the way, Smith introduces<br />

the reader to the important literature <strong>of</strong> the movement and places in proper<br />

order those theological antagonists who opposed it.<br />

In addition to showing the history <strong>of</strong> the movement, Smith also gives the reader an<br />

introduction to some <strong>of</strong> the salient doctrinal particularities that made it the object <strong>of</strong><br />

opprobrium among theologically-minded Baptists. Although both Sandemanianism<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<strong>–</strong>

This past April the <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> held a miniconference<br />

to remember the pastors and preachers<br />

expelled from the Anglican Church on August 24,<br />

1662, a few <strong>of</strong> whom subsequently became Baptists. A er<br />

the restoration <strong>of</strong> the monarchy in 1660, the state church<br />

was determined to enforce a uniformity <strong>of</strong> worship, and<br />

hence secured the passage <strong>of</strong> a body <strong>of</strong> legislation known<br />

as the Clarendon Code that made worship outside <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Church <strong>of</strong> England illegal. Many could not go along with<br />

this legislation and were forced into disobedience to the state out <strong>of</strong> a desire to obey<br />

God rst and foremost.<br />

Among those who su ered was Abraham Cheare (1626<strong>–</strong>1668), pastor <strong>of</strong> the Calvinistic<br />

Baptist church at Plymouth. First imprisoned in 1661 for his Baptist convictions,<br />

he was to be in prison for the greater part <strong>of</strong> the next seven years till his death<br />

in 1668. His rst imprisonment, for three months, was in the county jail in Exeter,<br />

which was described by one contemporary as “a living tomb, a sink <strong>of</strong> lth, pr<strong>of</strong>aneness<br />

and pro igacy.” On August 24, 1662, he was forced to leave his church by reason<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Act <strong>of</strong> Uniformity and subsequently re-arrested. He spent the next three years<br />

in prison in Exeter. He was released in August 1665, only to be arrested a third time<br />

when he resumed preaching in Plymouth. He was incarcerated on Drake’s Island in<br />

Plymouth Sound where he died a er some months <strong>of</strong> illness in 1668.<br />

A er his death some letters <strong>of</strong> his were published in a volume entitled <strong>Word</strong>s in<br />

Season (1668). In one <strong>of</strong> these letters, Cheare, who was not a boastful man, could say<br />

<strong>of</strong> his own case, a er more than ve years <strong>of</strong> imprisonment: “I have never yet seen<br />

the least reason and (I praise Christ my Lord) never been under an hour’s temptation,<br />

to relinquish or repent <strong>of</strong> my testimony in word or deed to any one persecuted<br />

truth <strong>of</strong> Christ for which I su er.” Such a man has much to teach us.<br />

And so does Hercules Collins, about whom Steve Weaver, a Junior Fellow <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies and a PhD candidate at the Southern Seminary,<br />

writes in one <strong>of</strong> the lead articles <strong>of</strong> this issue. Steve originally gave this paper<br />

at the April mini-conference noted above and we are thankful that we can publish it<br />

here as a model <strong>of</strong> how to learn from our Baptist forebears about su ering and persecution.<br />

Also featured in this issue is an article by Keith Grant, who is doing a PhD in<br />

history at the University <strong>of</strong> New Brunswick, on <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> as a preacher. It originally<br />

appeared in CRUX magazine, published by Regent College in Vancouver, and<br />

is an excellent example <strong>of</strong> the mini-renaissance that is taking place in <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong><br />

studies. May we see many more examples <strong>of</strong> such ne research in the days to come.<br />

Michael A.G. Haykin<br />

Director, e <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> <strong>Center</strong> for Baptist Studies<br />

<br />

<br />

<strong>of</strong> Evangelical Anglican chaplains in India, which included<br />

the missionary Henry Martyn.<br />

15 Timothy Dwight (1752<strong>–</strong>1817), the grand-son <strong>of</strong> Jonathan<br />

Edwards, was a Congregationalist minister and theologian,<br />

and one <strong>of</strong> the major religious gures <strong>of</strong> his day. He<br />

became president <strong>of</strong> Yale in 1795.<br />

16 is is a reference to Jonathan Edwards, Jr., the son<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jonathan Edwards, Sr. and uncle <strong>of</strong> Timothy Dwight. He<br />

was o en called “Dr. Edwards” as a way <strong>of</strong> distinguishing<br />

him from his father. Ryland refers to him thus a couple<br />

<strong>of</strong> lines later in the letter. e younger Edwards attended<br />

the College <strong>of</strong> New Jersey (now Princeton University) and<br />

also studied under Joseph Bellamy. Although only thirteen<br />

when his father died, he had a similar career, involving<br />

stormy relations with the churches he pastored, ending up<br />

as a college president (Union College in Schenectady, New<br />

York) and dying in his mid-50s. Edwards was a leading representative<br />

<strong>of</strong> New Divinity theology.<br />

17 e “dear grandfather” is Jonathan Edwards, Sr., the<br />

leading American theologian <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century.<br />

18 e Evangelical Magazine was an inter-denominational<br />

publication founded in 1793. Ryland, along with his close<br />

friend <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>, and other Baptists frequently published<br />

letters and articles in this magazine till a distinct Baptist<br />

publication, e Baptist Magazine, was founded in 1809.<br />

19 John Webster Morris (1763<strong>–</strong>1836), owned a press at<br />

Clipstone, England, and pastored the Baptist church there.<br />

Morris also wrote the Memoirs <strong>of</strong> the Life and Writing <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Rev. <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> (London, 1816).<br />

20 e Biblical Magazine, a short-lived but in uential<br />

Baptist magazine, was edited by Morris and lasted from<br />

1801<strong>–</strong>1803 when it merged with e eological Magazine.<br />

Andover-Newton eological Seminary and Southwestern<br />

Baptist eological Seminary have complete sets <strong>of</strong> this<br />

publication.<br />

21 <strong>Fuller</strong>’s work against the Deists was called e Gospel<br />

its own Witness; or, the Holy and Divine Harmony <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Christian Religion Contrasted with the Immorality and Absurdity<br />

<strong>of</strong> Deism (Clipstone: J. W. Morris, 1799).<br />

22 John Smalley was an American Congregationalist<br />

minister who studied under Joseph Bellamy and was also<br />

in uenced through his extensive reading <strong>of</strong> the elder Jonathan<br />

Edwards’ works. He mentored Nathaniel Emmons (see<br />

above, note 10) and Ebenezer Porter (1772<strong>–</strong>1834), who became<br />

an in uential pr<strong>of</strong>essor at and President <strong>of</strong> Andover<br />

Seminary.<br />

23 e sermon on Jeroboam is a reference to a fast day<br />

sermon that Nathanael Emmons delivered in Wrentham,<br />

Massachusetts on April 9, 1801, using 2 Kings 17:21 as his<br />

text. Emmons did not mention President omas Je erson<br />

by name, but it is quite clear from his sermon that he is<br />

equating Je erson with Jeroboam. Emmons, like the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

the New England Congregationalists, was a Federalist and<br />

was disappointed with the election <strong>of</strong> Je erson in 1801. Jefferson<br />

won the election by only one vote when the election<br />

was sent to the House <strong>of</strong> Representatives. e loser was Aaron<br />

Burr (1756<strong>–</strong>1836), a grand-son <strong>of</strong> Jonathan Edwards, Sr.,<br />

who then became Vice-President. While Baptists did not<br />

approve <strong>of</strong> Je erson’s religious views, they welcomed him<br />

because he took their side in the debate over the separation<br />

<strong>of</strong> church and state.<br />

NEW TITLES FROM Joshua Press<br />

Joy unspeakable and full <strong>of</strong> glory:<br />

<strong>The</strong> piety <strong>of</strong> Samuel and Sarah Pearce<br />

Edited and introduced by<br />

Michael A.G. Haykin · 248 pgs<br />

ISBN 978-1-894400-48-0<br />

CAN$21.99 · US$21.99<br />

<br />

<strong>The</strong> Christian Mentor | Volume 2<br />

<strong>The</strong> Reformers and Puritans as<br />

spiritual mentors: “Hope is kindled”<br />

By Michael A.G. Haykin · 196 pgs<br />

ISBN 978-1-894400-39-8<br />

CAN$19.99 · available as eBook<br />

CANADA Sola Scriptura Ministries<br />

<br />

USA Cumberland Valley Bible Book Service

M[anuscrip]ts were likely to fall. 17 I hope<br />

God will preserve them from being lost.<br />

I wish I had press’d Dr. Edwards to favor<br />

me w[i]th a few more Serm[ons]. I have<br />

one, or rather two, w[hi]ch I transcribed<br />

sev[era]l years ago for the Evang[elica]<br />

l Magazine. 18 ey declined inserting<br />

them, but Morris 19 pub[lished] them in<br />

the Biblical Magazine. 20<br />

Bro[ther] <strong>Fuller</strong> has lately met w[i]<br />

th some warm and unkind opposition<br />

on acc[oun]t <strong>of</strong> a Note in his B[oo]k<br />

ag[ains]to the Deists, 21 approaching to<br />

the views <strong>of</strong> Dr Edwards & Smalley respecting<br />

the Atonem[en]t. 22<br />

I pray God that you may enjoy much<br />

<strong>of</strong> his presence here, as you are advancing<br />

nearer to his blessed rest. I am now<br />

turned <strong>of</strong> 50. May we have an happy<br />

Meeting before the throne.<br />

I am Dear Sir your’s a ectionately,<br />

John Ryland<br />

* is sermon on Jeroboam 23 seems to me an Outrage<br />

on all decent Regard for Government. Let Jefferson<br />

be what he may as to Religion. I suppose he<br />

got his authority in as legal a way as Nero, or perhaps<br />

as any Monarch now upon Earth. All Respect<br />

for the powers that be is quite set aside if Christians<br />

may so directly insult the chief Magistrate <strong>of</strong><br />

a country.<br />

is a graduate <strong>of</strong><br />

the University <strong>of</strong> Albany with an M. A. in<br />

English. He is a writer and owns the Book<br />

Hound, an antiquarian bookstore in Amsterdam,<br />

NY. He attends the Bible Baptist<br />

Church in Galway, NY.<br />

_____________________<br />

1 is letter is in the personal possession <strong>of</strong> Mr. Craig<br />

Fries <strong>of</strong> Amsterdam, New York, and is published with his<br />

permission.<br />

2 For Hopkins’ detailed response to Ryland, see his Letter<br />

to John Ryland, September 1803 [ e Works <strong>of</strong> Samuel<br />

Hopkins, D.D. (Boston: Doctrinal Tract Society, 1865), II,<br />

752<strong>–</strong>758].<br />

3 <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> (1754<strong>–</strong>1815), an English Particular<br />

Baptist and very close friend <strong>of</strong> Ryland, pastored the Baptist<br />

church in Kettering from 1782 until his death. He was the<br />

<br />

most in uential Baptist theologian <strong>of</strong> his day and played a<br />

key role in the founding <strong>of</strong> the Baptist Missionary Society<br />

in 1792.<br />

4 e Death Of Legal Hope (London, 1770) was a 123page<br />

essay written by Particular Baptist pastor, Abraham<br />

Booth (1734<strong>–</strong>1806), published in 1770, the year a er his<br />

ordination. It was based on the biblical text, Galatians 2:19,<br />

and sought to combat Antinomianism.<br />

5 <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s “Bedford Sermon” was probably God’s<br />

approbation <strong>of</strong> our labours necessary to the hope <strong>of</strong> success<br />

(Clipstone, 1801), delivered at the annual meeting <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Bedford Union, May 6, 1801. In 1802, two American editions<br />

also appeared, one published in Boston by Manning<br />

& Loring, frequent publishers <strong>of</strong> things Baptist, and one in<br />

New York by C. Davis.<br />

6 is is a reference to Bristol Baptist Academy. Ryland<br />

had become president <strong>of</strong> the academy in 1794.<br />

7 Among Hopkins’ “brethren” and the “New England<br />

Divines” mentioned later would be Joseph Bellamy<br />

(1719<strong>–</strong>1790), John Smalley (1734<strong>–</strong>1820), Stephen West<br />

(1735<strong>–</strong>1819), and Jonathan Edwards, Jr. (1745<strong>–</strong>1801). For<br />

a useful introduction to the theology <strong>of</strong> these men and<br />

their movement, which begins with Jonathan Edwards and<br />

ends with Edwards Amasa Parks (1808<strong>–</strong>1900), see Douglas<br />

A. Sweeney and Allen C. Guelzo, eds., e New England<br />

eology: From Jonathan Edwards to Edwards Amasa Park<br />

(Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2006).<br />

8 “Our Missionaries in Bengal” would have included<br />

William Carey (1761<strong>–</strong>1834), William Ward (1769<strong>–</strong>1823)<br />

and Joshua Marshman (1768<strong>–</strong>1837).<br />

9 Probably a reference to Nathan Strong (1748<strong>–</strong>1816)<br />

who graduated at the head <strong>of</strong> his class from Yale in 1769,<br />

tutored at Yale for a while and then pastored the First<br />

Church in Hartford, Connecticut for 42 years, commencing<br />

in 1774. He was the founder <strong>of</strong> e Connecticut Missionary<br />

Society and e Connecticut Evangelical Magazine, one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the rst monthly religious journals in the United States,<br />

which sought to promote the bene cial e ects <strong>of</strong> the Second<br />

Great Awakening. In 1796, he published a theological<br />

work entitled e Doctrine <strong>of</strong> Eternal Misery consistent with<br />

the In nite Benevolence <strong>of</strong> God. He was the son <strong>of</strong> Nathan<br />

Strong, Sr. (1717<strong>–</strong>1795) <strong>of</strong> Coventry, Connecticut, under<br />

whom Nathanael Emmons studied.<br />

10 Nathanael Emmons (1745<strong>–</strong>1840), was a graduate <strong>of</strong><br />

Yale and a Congregational minister who studied under Nathan<br />

Strong, Sr., <strong>of</strong> Coventry, Connecticut and John Smalley.<br />

A gi ed preacher and proli c writer, he trained 87 men<br />

for the ministry. While his theology is o en confused with<br />

that <strong>of</strong> Samuel Hopkins, it di ered in several key areas.<br />

11 Dr. Ezra Stiles (1746<strong>–</strong>1795) was an Old Light Congregationalist<br />

minister in Newport, Rhode Island and later<br />

president <strong>of</strong> Yale. He was tolerant and catholic by nature<br />

and sometimes traded pulpits with Samuel Hopkins who<br />

was a New Light Congregationalist. Stiles was a regular correspondent<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sir William Jones (see below, note 11). He<br />

was particularly interested in any information that Jones<br />

might have on the whereabouts <strong>of</strong> the ten “lost tribes” <strong>of</strong><br />

Israel and hoped that the Jews at Cochin might have some<br />

early Biblical manuscripts in their possession. For more information,<br />

see George Alexander Kohut, Ezra Stiles and the<br />

Jews: Selected Passages from His Literary Diary Concerning<br />

Jews and Judaism (New York: Phillip Cowen, 1902.)<br />

12 Sir William Jones (1746<strong>–</strong>1794), English philologist<br />

and jurist, was a Supreme Court judge in Calcutta, India<br />

for eleven years. He was the Founder <strong>of</strong> the Asiatic Society<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bengal.<br />

13 e Cochin Jews, also called the Malabar Jews, lived<br />

in the South Indian Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Cochin, which included<br />

the present-day city <strong>of</strong> Kochi. Some scholars have argued<br />

they settled there during the time <strong>of</strong> King Solomon. ey<br />

were persecuted by the Portuguese when the colony came<br />

under their control. England took control in 1795. Few Jews<br />

remain today as they either have emigrated to Israel or converted<br />

to Christianity.<br />

14 Possibly Rev. David Brown (1762<strong>–</strong>1812), a Cambridge<br />

graduate who, greatly in uenced by Charles Simeon, became<br />

an Evangelical chaplain <strong>of</strong> the East India Company<br />

and Provost <strong>of</strong> Fort William College, established in Calcutta<br />

in 1800. Brown was considered the leader <strong>of</strong> a group<br />

<br />

<br />

<strong>–</strong><br />

here is evangelical theology,<br />

and there is evangelical piety: Is<br />

there also evangelical pastoral<br />

theology? Did the rise <strong>of</strong> evangelicalism<br />

in the eighteenth century change what it<br />

meant to be a pastor? 1<br />

e preaching <strong>of</strong> <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong><br />

(1754<strong>–</strong>1815) suggests that yes, evangelical<br />

emphasis on the cross <strong>of</strong> Christ,<br />

conversion, and heartfelt experience did<br />

indeed lead to a transformed pastoral<br />

theology. is change was not so much<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> new pastoral duties, as much<br />

as a renewal <strong>of</strong> the character <strong>of</strong> the main<br />

pastoral tasks, as it were, from within.<br />

ere is, then, a distinctively evangelical<br />

approach to pastoral theology.<br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s adoption <strong>of</strong> a warmly<br />

evangelical theology certainly transformed<br />

his own pastoral ministry; from<br />

the beginning, he knew that “this reasoning<br />

would a ect the whole tenor <strong>of</strong><br />

my preaching.” 2 T<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> was also the leading<br />

gure in the transformation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

English Particular Baptist churches in<br />

the late eighteenth century, and played a<br />

central role in the launch <strong>of</strong> the modern<br />

missionary movement. His evangelical<br />

Calvinism, which drew signi cantly on<br />

Jonathan Edwards (1703<strong>–</strong>1758), became<br />

known as “<strong>Fuller</strong>ism” in his own lifetime.<br />

e evangelical transformation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<br />

late eighteenth-century church is usually<br />

described in its outward aspects: widespread<br />

itinerancy, international missions,<br />

and voluntary societies alongside<br />

the congregation. 3 And, indeed, <strong>Andrew</strong><br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> was a leader in such expansionist<br />

activity, himself a village preacher, an<br />

administrator and advocate for the Baptist<br />

Missionary Society, and a theologian<br />

whose moderate Calvinism enabled—<br />

even obligated—such evangelical initiatives.<br />

But the weekly congregational<br />

preaching <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> and his contemporaries<br />

did not remain static while evangelical<br />

concerns produced change elsewhere.<br />

e evangelical transformation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the church meant not only preaching<br />

in new places, but also preaching<br />

in a new way. e pastoral theology <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> demonstrates how evangelical<br />

theology and piety in uenced his<br />

preaching, a renewal that was particularly<br />

evident in his conviction that preaching<br />

be plain in composition and delivery,<br />

evangelical in content and concern, and<br />

a ectionate in feeling and application.<br />

“He who would be generally agreeable<br />

to dissenters,” wrote Philip Doddridge<br />

(1702<strong>–</strong>1751) in the early eighteenth<br />

century, “must be an evangelical, an experimental,<br />

a plain and an a ectionate<br />

preacher.” 4 Such a preacher was <strong>Andrew</strong><br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>. A diarist from his Northampton-

shire congregation styled his ministry<br />

as “very a ecting and evangelical,” and<br />

his sermons as “truly evangelical, melting<br />

and a ectionate discourses.” 5 e<br />

qualities which were most characteristic<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s preaching—a plain style <strong>of</strong><br />

address, evangelical doctrine, and the<br />

personal language <strong>of</strong> the heart—were<br />

indicative <strong>of</strong> the evangelical renewal <strong>of</strong><br />

English Dissenting pastoral theology at<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century.<br />

“ e Simplicity <strong>of</strong> the Gospel”: <strong>Fuller</strong>’s<br />

plain style <strong>of</strong> preaching<br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> embraced a “plain style”<br />

<strong>of</strong> address that was particularly well suited<br />

for his evangelical aims: vernacular in<br />

language, simple in composition, intentionally<br />

perspicuous, and more a ecting<br />

than a ected in its rhetoric.<br />

is plain style was not uniquely the<br />

product <strong>of</strong> evangelicalism, representative<br />

as it was <strong>of</strong> a more general move<br />

toward plain, unadorned prose in literature<br />

and correspondence, as well as<br />

homiletics. e style sought a common<br />

language, accessible by a wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

readers, an approach shared by Isaac<br />

Watts (1674<strong>–</strong>1748) in his hymnody:<br />

“ e Metaphors are generally sunk to<br />

the Level <strong>of</strong> vulgar Capacities, I have<br />

aim’d at Ease <strong>of</strong> Numbers and Smoothness<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sound, and endeavoured to make<br />

the Sense plain and obvious.” 6<br />

e trajectory <strong>of</strong> English sermon<br />

composition was away from the “metaphysical”<br />

style <strong>of</strong> Lancelot <strong>Andrew</strong>es<br />

(1555<strong>–</strong>1626) and John Donne (1572<strong>–</strong><br />

1631), and although Puritans were<br />

crucial in that shi , in time there was<br />

also a departure from the proliferation<br />

<strong>of</strong> subheadings that had characterized<br />

some Puritan preaching. ere emerged<br />

<br />

a fairly broad consensus as to simplicity<br />

in Protestant preaching across the theological<br />

spectrum, allowing, <strong>of</strong> course, for<br />

individual personality and theological<br />

content.<br />

e emphasis on plainness and simplicity<br />

in preaching was an important<br />

element <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s instructions about<br />

preaching, and his own sermons were<br />

characterized by clarity, applicability,<br />

and biblical language. One <strong>of</strong> the editors<br />

<strong>of</strong> his collected Works, Joseph Belcher,<br />

wrote <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s preaching, “You are<br />

struck with the clearness <strong>of</strong> his statements;<br />

every text is held up before your<br />

view so as to become transparent.” 7 Joseph<br />

Ivimey’s appraisal was that <strong>Fuller</strong><br />

“greatly excelled in the simplicity <strong>of</strong> his<br />

compositions.” 8<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the shaping in uences upon<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s appropriation <strong>of</strong> the plain style<br />

was the widely read Essay on the Composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> a Sermon by French Protestant<br />

Jean Claude (1616<strong>–</strong>1687). 9 In outlining<br />

general rules for sermons, Claude emphasized<br />

clarity and comprehension,<br />

warning that obscurity is “the most<br />

disagreeable thing in the world in a<br />

gospel-pulpit.” Rather, “a preacher must<br />

be simple and grave. Simple, speaking<br />

things full <strong>of</strong> good natural sense without<br />

metaphysical speculations; for none are<br />

more impertinent than they, who deliver<br />

in the pulpit abstract speculations,<br />

de nitions in form, and scholastic questions,<br />

which they pretend to derive from<br />

their texts.” 10 Claude’s translator, Robert<br />

Robinson, pithily contended: “Plainness<br />

in religion is elegance, and popular perspicuity<br />

true magni cence.” 11<br />

e impetus toward simplicity and<br />

plainness in art and rhetoric, Peter Auksi<br />

has argued, is a signi cant stream within<br />

not wholly surmount, tho I may perhaps<br />

be more favorably disposed toward your<br />

view than most persons in the [Kingdom?].<br />

I have feared also a temptation to dwell<br />

upon a few truths, and some <strong>of</strong> them the<br />

most di cult truths <strong>of</strong> Religion, to the<br />

neglect <strong>of</strong> other parts <strong>of</strong> Revelation. I<br />

hope all your friends will guard against<br />

this evil.<br />

Another Danger to w[hi]ch some <strong>of</strong><br />

the New England Divines seem exposed,<br />

is the Neglect <strong>of</strong> Scripture Authority,<br />

and a method <strong>of</strong> proving theological<br />

points more by reason than by the Bible.<br />

But nothing puzzles me so much as<br />

the views some <strong>of</strong> you seem to entertain,<br />

respecting the divine Agency in<br />

respect <strong>of</strong> Sin. Must we almost lay aside<br />

the Business <strong>of</strong> proving that God is the<br />

Author <strong>of</strong> all the moral good in the Universe,<br />

to spend our Lifetime in proving<br />

that he is also in some sense the Author<br />

<strong>of</strong> all the moral Evil in the world; and yet<br />

that this is no Excuse for Sin? I am afraid<br />

that if we get the former part <strong>of</strong> this<br />

last Notion into Men’s hands, we shall<br />

never be able to prevent their drawing a<br />

contrary Conclusion. Some w[ould] be<br />

ready to stone us, before we could make<br />

them understand us on this subject, and<br />

others w[ould] surely shi o all blame<br />

from themselves upon the most High. I<br />

wish much to know how your brethren<br />

w[ould] answer the pleas <strong>of</strong> the Hindoos,<br />

if they were in the Case <strong>of</strong> our Missionaries<br />

in Bengal 8 and shall therefore inclose<br />

a few Extracts from the last journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> my friend Marshman. It w[ould] be<br />

a high grati cation to receive your own<br />

Remarks but if your weak state <strong>of</strong> health<br />

sh[ould] prevent, or if you should be<br />

gone to Heaven before this reaches you,<br />

<br />

I sh[ould] be glad for this Letter to be<br />

given to [Mr.?] Strong, 9 or some friend<br />

<strong>of</strong> nearly the same stamp, and w[ould]<br />

thank him for his Observations. I don’t<br />

want it to go to any one who pushes the<br />

Matter still further, e.g. Dr Emmons*<br />

seems to be such a one. 10 I cannot relish<br />

his representation <strong>of</strong> sev[era]l subjects,<br />

particularly his idea <strong>of</strong> a Christian popping<br />

into a State <strong>of</strong> perfection and out<br />

again interchangeably, all the days <strong>of</strong> his<br />

Life etc.<br />

I am strongly persuaded that I need<br />

not make an Apology to you for so freely<br />

mentioning the points on which I feel<br />

most di culty; I believe that I and my<br />

most intimate friends are more disposed<br />

to canvass the subjects on which you<br />

have written impartially, than any others<br />

you w[ould] nd in England. And it<br />

must be some advantage to you, to see<br />

wherein subjects strike those who were<br />

unused to the discussion, and cause<br />

them to fear for bad consequences.<br />

Surely it w[ould] be well if all Christians<br />

w[ould] labor earnestly a er the investigation<br />

<strong>of</strong> truth, without being unduly<br />

in uenced either by their attachment to<br />

old ideas and phrases on the one hand,<br />

or by the a ectation <strong>of</strong> novelty on the<br />

other.<br />

Do you know whether any thing has<br />

been sent to America in reply to Dr Ezra<br />

Stiles[’] 11 letter to Sir W[illia]m Jones 12<br />

about the Jews at Cochin etc. 13 I have<br />

begged our brethren to enquire, and nd<br />

that [Mr.?] Brown 14 is now likely to prosecute<br />

the business with earnestness.<br />

I wrote long since to Dr. Dwight, 15<br />

and sent him several pamphlets, begging<br />

for some Acc[oun]t <strong>of</strong> his Uncle’s<br />

Death 16 and wishing much to know<br />

into what hands his d[ea]r grandfather’s

them without a Reply, if he sh[ould] feel<br />

himself convinced; or else to show by a<br />

Reply, how calmly and friendly he can<br />

discuss the subject.<br />

My Station in the Academy 6 leaves<br />

me less time for correspond[ence] and<br />

friendly Discussion than I could wish,<br />

& indeed for Reading also. It has sometimes<br />

seemed to me as if you, my d[ea]<br />

r sir, and some <strong>of</strong> your brethren, 7 expected<br />

an opportunity to be given, a er<br />

[regeneration?], <strong>of</strong> almost always trying<br />

how the Law w[ould] operate on the renewed<br />

mind, before a man tho’t <strong>of</strong> the<br />

gospel. at he might rst show the effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> Grace on a hopeless mind, and<br />

then on a mind w[hi]ch embraced the<br />

hope <strong>of</strong> the gospel. But is it not a Fact,<br />

that there are few souls regenerated,<br />

but what have already heard the gospel<br />

sev[era]l times, and o en many? Now<br />

must they not disbelieve the Gospel, if<br />

they conclude there is no possibility <strong>of</strong><br />

their being saved? But if they allow the<br />

<br />

gospel to be true, must they not allow<br />

that it is possible they may be saved;<br />

yea they certainly shall be saved, unless<br />

they reject the Counsel <strong>of</strong> God ag[ains]<br />

t themselves? What call have they to be<br />

willing to be damned, when God assures<br />

them Christ is able & willing to<br />

save them? and can be glorify’d more in<br />

their Salv[ation] than in their Damnation?<br />

It also seems strange that a Man<br />

sh[ould] from Love to God, be willing<br />

for ever to hate God, & blaspheme him.<br />

at a sinner ought to own the perfect<br />

Equity <strong>of</strong> his Condemnat[ion], and to<br />

consider the very Sanction <strong>of</strong> the Law as<br />

an expression <strong>of</strong> divine Equity and Love<br />

<strong>of</strong> order, etc. I readily admit. But do we<br />

not puzzle people needlessly, to require<br />

them to be willing to be eternally tormented,<br />

& even eternally wicked, when<br />

Christ came on purpose to save them<br />

both from torment and sin?<br />

I am persuaded you will excuse my<br />

freely stating di culties w[hi]ch I can-<br />

the Christian tradition. 12 By removing<br />

or reducing excess, arti ce, and needless<br />

complexity, the “plain style” makes<br />

possible at least three aims: “Plainness in<br />

expression enables audiences to measure<br />

without distraction the spiritual, moral<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> the agent; to attend to the substance<br />

as opposed to the mere covering<br />

<strong>of</strong> expression; and to concentrate on<br />

their relationship to the prime giver <strong>of</strong><br />

the gi s being enjoyed, God.” 13<br />

If it did not originate with them, still<br />

the plain style was widely and e ectively<br />

employed by evangelicals, who<br />

recognized that the increasingly voluntaristic<br />

relationship between preachers<br />

and hearers required an address more<br />

understandable and personal. <strong>Andrew</strong><br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s use <strong>of</strong> the plain style re ects his<br />

evangelical emphases on the centrality<br />

<strong>of</strong> the cross, on personal religious experience,<br />

and on addressing the gospel<br />

to as many hearers as possible. <strong>Fuller</strong><br />

employed the language <strong>of</strong> simplicity to<br />

encompass the whole <strong>of</strong> the preaching<br />

experience, taking in content, composition,<br />

delivery, and even motivations.<br />

He emphasized that plainness <strong>of</strong> pulpit<br />

speech best re ected the perspicuity <strong>of</strong><br />

the Scriptures, and was most conducive<br />

to usefulness and personal application<br />

for a wide range <strong>of</strong> hearers.<br />

Preaching, insisted <strong>Fuller</strong>, should be<br />

plain and simple so that its central content—the<br />

gospel <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ—could<br />

be clearly communicated. is gospel, he<br />

said, is a message <strong>of</strong> deep wisdom, “and<br />

therefore we ought to possess a deep insight<br />

into it, and to cultivate great plainness<br />

<strong>of</strong> speech.” 14 Simplicity should also<br />

be the standard by which its subject matter<br />

should be selected. In an ordination<br />

sermon titled “ e Satisfaction Derived<br />

<br />

from Godly Simplicity” on 2 Corinthians<br />

1:12, <strong>Fuller</strong> contrasted “ eshly wisdom”<br />

with “the grace <strong>of</strong> God” and noted<br />

that preaching that is characterized by<br />

the latter will be simple and sincere. Of<br />

the matter <strong>of</strong> preaching, godly simplicity<br />

means that “the doctrine we preach<br />

will not be selected to please the tastes<br />

<strong>of</strong> our hearers, but drawn from the Holy<br />

Scriptures.” 15<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> was likewise concerned that<br />

the language, as well as the doctrines,<br />

<strong>of</strong> sermons be drawn from the language<br />

<strong>of</strong> Scripture. “ ere are many sermons,<br />

that cannot fairly be charged with untruth,<br />

which yet have a tendency to lead<br />

o the mind from the simplicity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

gospel.” 16 Convinced <strong>of</strong> the perspicuity<br />

and inspiration <strong>of</strong> the Scriptures, he<br />

emphasized the Spirit’s witness to the<br />

simplicitas evangelica, rather than the<br />

use <strong>of</strong> language and terminology that<br />

instead highlighted the cleverness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

speaker: “To be sure, there is a way <strong>of</strong><br />

handling Divine subjects a er this sort<br />

that is very clever and very ingenious;<br />

and a minister <strong>of</strong> such a stamp may<br />

commend himself, by his ingenuity, to<br />

many hearers: but, a er all, God’s truths<br />

are never so acceptable and savoury to a<br />

gracious heart as when clothed in their<br />

own native phraseology.” 17 Plainness as<br />

a standard for the subject matter <strong>of</strong> sermons<br />

meant for <strong>Fuller</strong> that they focus on<br />

the gospel <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ, that their language<br />

be scriptural, and that their aim<br />

be the salvation <strong>of</strong> their hearers: “characterized<br />

by simplicity; not thinking <strong>of</strong><br />

ourselves, but <strong>of</strong> Christ and the salvation<br />

<strong>of</strong> souls.” 18<br />

Plainness <strong>of</strong> style and composition<br />

also meant that preaching would be<br />

more than “merely an art,” and that it

would be focused in its construction,<br />

and understandable and useful to the<br />

least educated <strong>of</strong> hearers. 19 A sermon,<br />

insisted <strong>Fuller</strong>, should not be a “mob <strong>of</strong><br />

ideas,” multiplying headings and themes,<br />

but should instead have “unity <strong>of</strong> design.”<br />

20 “A preacher, then, if he would<br />

interest a judicious hearer, must have an<br />

object at which he aims, and must never<br />

lose sight <strong>of</strong> it throughout his discourse,”<br />

something which <strong>Fuller</strong> wrote was “<strong>of</strong><br />

far greater importance than studying<br />

well-turned periods, or forming pretty<br />

expressions.” He wrote that it is this<br />

unity and simplicity that “nails the attention<br />

<strong>of</strong> an audience.” 21 A sermon that<br />

is composed <strong>of</strong> a central theme is an aid<br />

to the judicious and attentive hearer, but<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> was also concerned that the less<br />

educated in the congregation could also<br />

comprehend and apply the message:<br />

In general, I do not think a minister<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ should aim at ne<br />

composition for the pulpit. We ought<br />

to use sound speech, and good sense;<br />

but if we aspire a er great elegance <strong>of</strong><br />

expression, or become very exact in<br />

the formation <strong>of</strong> our periods, though<br />

we may amuse and please the ears <strong>of</strong><br />

a few, we shall not pro t the many,<br />

and consequently shall not answer<br />

the great end <strong>of</strong> our ministry. Illiterate<br />

hearers may be very poor judges <strong>of</strong><br />

preaching; yet the e ect which it produces<br />

upon them is the best criterion<br />

<strong>of</strong> its real excellence. 22<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s desire for simplicity likewise<br />

included studied reticence in delivery,<br />

as well as composition. He eschewed<br />

performance as much as scholasticism:<br />

“Avoid all a ectation in your manner—<br />

<br />

Do not a ect the man <strong>of</strong> learning by useless<br />

criticisms: many do this, only to display<br />

their knowledge. Nor yet the orator,<br />

by high-sounding words, or airs, or gestures.<br />

Useful learning and an impressive<br />

delivery should by no means be slighted;<br />

but they must not be a ected.” 23 As we<br />

will see below, rather than a ected gestures<br />

or emotions, <strong>Fuller</strong> urged preachers<br />

to enter into their ministry with<br />

true godly feelings and a ection, which<br />

would be communicated more authentically<br />

than those that were contrived.<br />

Finally, preaching that is plain and<br />

perspicuous to the hearer must be<br />

grounded, wrote <strong>Fuller</strong>, in the straightforward,<br />

diligent, and spiritual study <strong>of</strong><br />

the preacher: “To preach the gospel as<br />

we ought to preach it requires, not the<br />

subtlety <strong>of</strong> the metaphysician, but the<br />

simplicity <strong>of</strong> the Christian.” 24 Preacher<br />

and hearer alike come to the gospel in its<br />

simplicity, so that, spiritually discerned,<br />

it can be practically applied.<br />

“Preaching Christ”: e Evangelical nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s preaching<br />

To say that <strong>Fuller</strong> preached the gospel,<br />

or that he was an evangelical preacher,<br />

is not to say enough. <strong>Fuller</strong> himself felt<br />

the need to de ne and defend the gospel<br />

and the evangelical nature <strong>of</strong> preaching<br />

ministry in his own day, and delineating<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s convictions about preaching<br />

helps us to appreciate what made him an<br />

evangelical. <strong>Fuller</strong> was concerned with<br />

just this further de nition <strong>of</strong> evangelical<br />

preaching when he said, in an ordination<br />

charge, “I have heard complaints<br />

<strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> our young ministers, that<br />

though they are not heterodox, yet they<br />

are not evangelical; that though they do<br />

not propagate error, yet the grand, es-<br />

This letter <strong>of</strong> the English Baptist<br />

leader John Ryland, Jr.<br />

(1753<strong>–</strong>1825) to the American<br />

theologian and New Divinity theologian<br />

Samuel Hopkins (1721<strong>–</strong>1803), who<br />

had served the First Congregationalist<br />

Church in Newport, Rhode Island, since<br />

1769, is an extremely important text. As<br />

it reveals, while Ryland and his friends<br />

were sympathetic to the New Divinity,<br />

they were also critical <strong>of</strong> certain elements<br />

<strong>of</strong> this American theological perspective.<br />

Ryland is especially, and rightly,<br />

dubious about one <strong>of</strong> the hallmarks<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hopkinsianism, as Hopkins’ system<br />

<strong>of</strong> thought became known, namely, his<br />

argument about the willingness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

believer to be damned for the glory <strong>of</strong><br />

God. Ryland points out the theological<br />

and spiritual incongruity <strong>of</strong> this tenet.<br />

Other concerns <strong>of</strong> Ryland include the<br />

tendency to speculation and failure to<br />

ground theology rmly in the subsoil <strong>of</strong><br />

Scripture. e letter also reveals Ryland’s<br />

deep admiration <strong>of</strong> the mentor who was<br />

common to both he and Hopkins, Jonathan<br />

Edwards (1703<strong>–</strong>1758). He would<br />

have been delighted to know that most<br />

<strong>of</strong> Edwards’ manuscripts were preserved<br />

and are now available either in print or<br />

on-line.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

e accompanying photograph <strong>of</strong> a<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> the letter shows the way that<br />

Ryland used virtually every inch and<br />

both sides <strong>of</strong> a foolscap sheet to write<br />

the letter. e only modernization <strong>of</strong> the<br />

text that has been made in the following<br />

transcription has been the replacement<br />

<strong>of</strong> underscore marks at the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> sentences by full stops or the occasional<br />

comma. e footnotes have been<br />

added by the editors. e asterisk a er<br />

Nathanael Emmons’ name is part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

original letter and indicates an appended<br />

comment <strong>of</strong> Ryland. 1 is letter has<br />

not been published before.<br />

Dr. Hopkins Feb. 21 1803 2<br />

Dear Sir<br />

Bro[ther] <strong>Fuller</strong> 3 lately sent me a Letter<br />

from you, which had been 3 y[ea]rs in<br />

coming, & a few days ago I rec[eived]<br />

yours to my self. Before then I had heard<br />

a false report that you were gone to<br />

Heaven, or I sh[ould] have written long<br />

ago to you. o[ugh] I believe I have<br />

never heard from you since I sent you<br />

Booth’s D[ea]th <strong>of</strong> legal hope etc. 4 I am<br />

much obliged to you for your last favor;<br />

and have copied, and sent to Bro[ther]<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>, your Remarks on his Bedford<br />

Sermon. 5 I advised him either to print

home in the thought <strong>of</strong> Evans. God’s<br />

decree <strong>of</strong> election was an eternal one<br />

but could be reconciled with the biblical<br />

warrant to call to repentance all the<br />

unregenerate. In fact, the reality <strong>of</strong> a<br />

once-and-for-all atonement provided a<br />

real opportunity for salvation. Without<br />

it, men were le with “unhealed wounds”<br />

and hopeless when it came to being<br />

saved. 5 So instead <strong>of</strong> over-analyzing the<br />

limited nature <strong>of</strong> the atonement Evans<br />

magni ed the full provision <strong>of</strong> Christ’s<br />

work for needy sinners. e doctrine <strong>of</strong><br />

Christ cruci ed “proves itself to be indeed<br />

the provision <strong>of</strong> in nite wisdom<br />

and in nite power to e ect salvation <strong>of</strong><br />

the soul.” ose who trust in it “feel the<br />

energy <strong>of</strong> it working e ectually in them.” 6<br />

e atonement for Evans is not a cold and<br />

limiting doctrine but something vibrant,<br />

accomplishing salvation for an unknown<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> people. Bebbington, discussing<br />

the shi away from Hyper-Calvinism<br />

in the English Baptists <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth<br />

century writes, “ e old understanding<br />

dwelt on the limitation <strong>of</strong> the bene ts<br />

<strong>of</strong> the atonement to a few; the later position<br />

accepted that the potential number<br />

<strong>of</strong> converts was immense.” 7 Leaders<br />

like Evans saw God’s love in the atonement<br />

opening the door <strong>of</strong> salvation to<br />

anyone who called upon Christ’s name.<br />

In fact, Evans uses the same language as<br />

<strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong> (1754-1815), the great<br />

leader <strong>of</strong> the Baptist mission movement,<br />

in describing the atonement as a “heart<br />

cheering doctrine” and “well worthy <strong>of</strong><br />

all acceptation.” 8 Where the Hyper-Calvinist<br />

saw limits to the gospel, Evans saw<br />

opportunity and frequently used means,<br />

especially in pastoral ministry and theological<br />

education, to spread the good<br />

news.<br />

<br />

received his M.Div. from<br />

the Southern Baptist eological Seminary<br />

where he currently serves as the Associate Director<br />

<strong>of</strong> Admissions. He is the Highschool<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> Sojourn Student Ministries at Sojourn<br />

Community Church’s Mid-town campus<br />

in Louisville, Ky.<br />

_____________________<br />

1 David Bebbington, “British Baptist Crucicentrism since<br />

the Late Eighteenth Century: Part 1,” e Baptist Quarterly,<br />

44.4 (October 2011), 224.<br />

2 Caleb Evans, Christ Cruci ed; or the Scripture Doctrine<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Atonement Brie y Illustrated and Defended in Four<br />

Discourses upon that Subject (Bristol: William Pine, 1789),<br />

215. 3 Evans, Christ Cruci ed, 198<strong>–</strong>199.<br />

4 is description <strong>of</strong> Hyper-Calvinism is drawn from<br />

John Piper, “Holy Faith, Worthy Gospel, World Vision: <strong>Andrew</strong><br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s Broadsides Against Sandemanianism, Hyper-<br />

Calvinism, and Global Unbelief,” Presentation at the Desiring<br />

God Conference for Pastors, Minneapolis, MN, February<br />

6, 2007. (on-line). Accessed 25 October 2011. Available from<br />

(http://www.desiringgod.org/resource-library/biographies/<br />

holy-faith-worthy-gospel-world-vision).<br />

5 Evans, Christ Cruci ed, vi.<br />

6 Evans, Christ Cruci ed, 220.<br />

7 Bebbington, “British Baptist Crucicentrism since the<br />

Late Eighteenth Century,” 226.<br />

8 is quote is taken from Evans’ confession <strong>of</strong> faith at his<br />

ordination in Hugh Evans, A charge and Sermon, together<br />

with an Introductory Discourse, and Confession <strong>of</strong> Faith : Delivered<br />

at the Ordination <strong>of</strong> Caleb Evans, August 18, 1767, in<br />

Broad-Mead, Bristol (Bristol: Published by S. Farley, 1767),<br />

30.<br />

sential, distinguishing truths <strong>of</strong> the gospel<br />

do not form the prevailing theme <strong>of</strong><br />

their discourses.” 25 ose essential truths<br />

that by their prevalence distinguished<br />

evangelical from generally orthodox<br />

preaching focused on the person and<br />

work <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ. As <strong>Fuller</strong> told ministerial<br />

students, “the person and work<br />

<strong>of</strong> Christ must be the leading theme <strong>of</strong><br />

our ministry.” 26 Similarly, in an ordination<br />

charge <strong>Fuller</strong> declared “preaching<br />

Christ” to be “the grand theme <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Christian ministry.” He continued unequivocally,<br />

“Preach Christ, or you had<br />

better be any thing than a preacher. e<br />

necessity laid on Paul was not barely to<br />

preach, but to preach Christ.” 27<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s insistence on Christ as the criterion<br />

for preaching was representative<br />

<strong>of</strong> evangelical preaching, but it could,<br />

<strong>of</strong> course, have been otherwise. While<br />

the movement toward a plain style <strong>of</strong><br />

composition was more or less common<br />

across the theological boundaries <strong>of</strong><br />

the eighteenth century, the perceived<br />

purposes <strong>of</strong> preaching in the religious<br />

lives <strong>of</strong> hearers were more varied. High<br />

Calvinists, evangelical Calvinists, and<br />

evangelical Arminians had distinct,<br />

if overlapping, understandings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

agency <strong>of</strong> God, preacher, and hearers<br />

in the preaching event, and these were<br />

markedly di erent again from those <strong>of</strong><br />

Unitarians, Deists, and Universalists.<br />

e goal and content <strong>of</strong> preaching might<br />

be variously perceived as a reformation<br />

<strong>of</strong> morals, the cultivating <strong>of</strong> civil society,<br />

the encouragement <strong>of</strong> good works, or<br />

perhaps an exercise in classical rhetoric,<br />

and it is partly over against these competing<br />

visions <strong>of</strong> the preaching task that<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> wanted to de ne its evangelical<br />

nature:<br />

<br />

I have also heard many an ingenious<br />

discourse, in which I could not but<br />

admire the talents <strong>of</strong> the preacher;<br />

but his only object appeared to be to<br />

correct the grosser vices, and to form<br />

the manners <strong>of</strong> his audience, so as to<br />

render them useful members <strong>of</strong> civil<br />

society. Such ministers have an errand;<br />

but not <strong>of</strong> such importance as to<br />

save those who receive it, which su -<br />

ciently proves that it is not the gospel. 28<br />

Evangelical preaching’s emphasis<br />

upon the gospel <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ can be<br />

further delineated by examining, in<br />

turn, the centrality <strong>of</strong> the cross <strong>of</strong> Christ,<br />

and the zeal for conversion e ected by<br />

the preaching <strong>of</strong> that doctrine.<br />

e centrality <strong>of</strong> the cross <strong>of</strong> Christ<br />

e central doctrine <strong>of</strong> <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s<br />

preaching was the atoning death <strong>of</strong> Jesus<br />

on the cross, a theme described as<br />

“crucicentrism” by David Bebbington. 29<br />

Emphasizing the cross, <strong>Fuller</strong> wrote,<br />

“Every sermon should contain a portion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the doctrine <strong>of</strong> salvation by the death <strong>of</strong><br />

Christ. … A sermon, therefore, in which<br />

this doctrine has not a place, and I might<br />

add, a prominent place, cannot be a gospel<br />

sermon.” 30 Elsewhere, <strong>Fuller</strong> insisted:<br />

“ e death <strong>of</strong> Christ is a subject <strong>of</strong> so<br />

much importance in Christianity as to<br />

be essential to it. … It is not so much a<br />

member <strong>of</strong> the body <strong>of</strong> Christian doctrine<br />

as the life-blood that runs through<br />

the whole <strong>of</strong> it. e doctrine <strong>of</strong> the cross<br />

is the Christian doctrine.” 31 Understanding<br />

the atoning death <strong>of</strong> Jesus to be the<br />

unique source <strong>of</strong> salvation, <strong>Fuller</strong> urged<br />

that evangelical preaching give it repeated<br />

emphasis and great prominence.<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong>’s evangelical crucicentrism

was also expressed by emphasizing the<br />

cross’s connection and interrelation with<br />

other themes in doctrine, practice, and,<br />

therefore, preaching. Early in his Kettering<br />

ministry, he wrote in his diary,<br />

“‘Christ, and his cross be all my theme.’<br />

Surely I love his name, and wish to make<br />

it the centre in which all the lines <strong>of</strong> my<br />

ministry might meet!” 32 Later, to his<br />

father-in-law, <strong>Fuller</strong> wrote from Ireland,<br />

“ e doctrine <strong>of</strong> the cross is more dear<br />

to me than when I went. I wish I may<br />

never preach another sermon but what<br />

shall bear some relation to it.” 33 <strong>Fuller</strong><br />

believed that the whole <strong>of</strong> Scripture<br />

bears witness to Jesus, and that, therefore,<br />

expositions <strong>of</strong> any part <strong>of</strong> the Bible<br />

inevitably manifest something <strong>of</strong> his<br />

person or work: “If you preach Christ,<br />

you need not fear for want <strong>of</strong> matter. His<br />

person and work are rich in fullness. Every<br />

Divine attribute is seen in him. All<br />

the types pre gure him. e prophecies<br />

point to him. Every truth bears relation<br />

to him. e law itself must be so explained<br />

and enforced as to lead to him.” 34<br />

Re ecting on systematic theology, <strong>Fuller</strong><br />

asserted that “the centre <strong>of</strong> Christianity<br />

[is] the doctrine <strong>of</strong> the cross,” and that<br />

“the whole <strong>of</strong> the Christian system appears<br />

to be presupposed by it, included in<br />

it, or to arise from it.” 35 <strong>Fuller</strong>’s preaching<br />

could be distinguished from Deistic<br />

or moralistic—or even generally orthodox—preaching<br />

by the centrality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cross <strong>of</strong> Christ, and it is that prominence<br />

which marks it as evangelical.<br />

Zeal for conversion<br />

<strong>Fuller</strong> urged preachers to have a “zealous<br />

perseverance in the use <strong>of</strong> all possible<br />

means for the conversion <strong>of</strong> sinners.”<br />

36 Such a zeal for conversion, or<br />

<br />

conversionism, has been identi ed by<br />

David Bebbington as another <strong>of</strong> the<br />

de ning characteristics <strong>of</strong> evangelicalism.<br />

37 e emergence <strong>of</strong> such urgency<br />

about conversion was the most signi -<br />

cant development in <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Fuller</strong>’s<br />

pastoral theology. <strong>Fuller</strong> had grown up<br />

in a high Calvinist church in which the<br />

preacher had “little or nothing to say<br />

to the unconverted,” and as a young<br />

preacher himself he did not dare to “address<br />

an invitation to the unconverted to<br />

come to Jesus,” 38 a reticence grounded<br />

in a theological system which did not<br />

want to presume spiritual ability. From<br />

being reticent to o er his hearers the<br />

gospel, <strong>Fuller</strong> went on to write e Gospel<br />

Worthy <strong>of</strong> All Acceptation (1781), in<br />

which he made the case that all people<br />

not only have the capacity to respond<br />

to the gospel, but, indeed, have an obligation<br />

to do so: “Unconverted sinners<br />

are commanded, exhorted, and invited<br />

to believe in Christ for salvation.” 39 As<br />

David Bebbington has observed, <strong>Fuller</strong>’s<br />

articulation <strong>of</strong> “duty faith,” or the obligation<br />

<strong>of</strong> all people to respond to the<br />

gospel, was the essential di erence between<br />

evangelical and high Calvinists,<br />

who otherwise shared a great fund <strong>of</strong><br />

orthodox and Calvinist theology, a difference<br />

with great practical, or we might<br />

say pastoral, implications: “If believing<br />

was an obligation, preachers could press<br />

it on whole congregations. If it was not,<br />

they could merely describe it in the hope<br />

that God would rouse certain predetermined<br />

hearers to faith.” 40<br />

is duty on the part <strong>of</strong> hearers corresponded<br />

to the obligation <strong>of</strong> preachers:<br />

“It is the duty <strong>of</strong> ministers not only<br />

to exhort their carnal auditors to believe<br />

in Jesus Christ for the salvation <strong>of</strong> their<br />

n a day when Particular Baptists<br />

were declining in the face <strong>of</strong><br />

Hyper-Calvinism, Caleb Evans<br />

(1737<strong>–</strong>1791) promoted a cross-centered<br />

piety that emphasized the accessibility<br />

<strong>of</strong> salvation through the atoning work<br />

<strong>of</strong> Christ. As a pastor and educator<br />

this evangelistic perspective was passed<br />

down to his congregation and students<br />

at the Bristol Baptist Academy, where he<br />

served as the principal, thus helping to<br />

both sustain and revitalize the Particular<br />

Baptist movement.<br />

Historian David Bebbington captures<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> eighteenth-century<br />

Particular Baptist crucicentrism when<br />

he states that “the death <strong>of</strong> Christ was<br />

not so much a portion <strong>of</strong> the body <strong>of</strong><br />

Christian doctrine as its life-blood.” 1<br />

is sentiment is shared by Evans who<br />

considered the “whole system <strong>of</strong> salvation”<br />

as one “through the blood <strong>of</strong> the<br />

lamb.” 2 I<br />

In Evans’ thought, Christ is the<br />

pre-existing Son <strong>of</strong> God who came to<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

dwell in human esh. Due to the reality<br />

<strong>of</strong> sin it is only he, the God-man, who<br />

can o er full satisfaction for transgressions.<br />

At the cross, Christ is the “vicarious<br />

substituted victim” and guilt<br />

is transferred to him in place <strong>of</strong> sinful<br />

man. 3<br />

Now, Evans was deeply critical <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Hyper-Calvinism that prevailed in far<br />

too many Baptist circles in his day. In<br />

Hyper-Calvinism, justi cation was seen<br />

as an eternal act separated from active<br />

faith in Christ, setting in place a hard<br />

line between the elect and reprobate. In<br />

this system, the unregenerate are under<br />

no obligation to believe the gospel message.<br />

us it was viewed as cruelty to call<br />

a man to act upon that which he carried<br />

no power to accomplish. Salvation<br />

was relegated to a subjective knowing<br />

that one was among the elect for whom<br />

Christ died rather than an act <strong>of</strong> faith in<br />

the nished work <strong>of</strong> Christ. 4<br />

Such an understanding found no

9 Kevan, London’s Oldest Baptist Church, 43.<br />

10 Joseph Ivimey, A History <strong>of</strong> the English Baptists (London,<br />

1814), II, 448<strong>–</strong>449.<br />

11 Middlesex: Rolls, Books and Certi cates, Indictments,<br />

Recognizances, … 1667<strong>–</strong>1688, vol. 4.<br />

12 For a description <strong>of</strong> the horrors <strong>of</strong> the Newgate Prison<br />

during the seventeenth century, see Haykin, “Piety <strong>of</strong> Hercules<br />

Collins (1646/7<strong>–</strong>1702),” 14. See also Kelly Grovier, e<br />

Gaol: e Story <strong>of</strong> Newgate—London’s Most Notorious Prison<br />

(London: John Murray, 2008).<br />

13 Hercules Collins, Some Reasons for Separation from<br />

the Communion <strong>of</strong> the Church <strong>of</strong> England, and the Unreasonableness<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persecution Upon that Account. Soberly Debated<br />

in a Dialogue between a Conformist, and a Nonconformist<br />

(Baptist.) (London: John How, 1682), 20.<br />

14 omas Crosby, e History <strong>of</strong> the English Baptists<br />

(London: John Robinson, 1740), 129.<br />

15 See especially Roger Williams, e Bloudy Tenent <strong>of</strong><br />

Persecution (London, 1644), 2<strong>–</strong>3 and Collins, Some Reasons<br />

for Separation, 18<strong>–</strong>20.<br />

16 Collins, Some Reasons for Separation, 20.<br />

17 A Voice from the Prison. Or, Meditations on Revelations<br />

III.XI. Tending To the Establishment <strong>of</strong> Gods Little Flock, In<br />

an Hour <strong>of</strong> Temptation (London, 1684) and Counsel for the<br />

Living, Occasioned from the Dead: Or, A Discourse on Job<br />

III. 17,18. Arising from the Deaths <strong>of</strong> Mr. Fran. Bamp eld<br />

and Mr. Zach. Ralphson (London: George Larkin, 1684). A<br />

complete list <strong>of</strong> Collins’ works can be found in Devoted to<br />

the Service <strong>of</strong> the Temple, eds. Haykin and Weaver, 135<strong>–</strong>137.<br />

18 For biographical details on Bamp eld, see Richard L.<br />

Greaves, “Making the Laws <strong>of</strong> Christ His Only Rule’: Francis<br />

Bamp eld, Sabbatarian Reformer” in his Saints and Rebels:<br />

Seven Nonconformists in Stuart England (Macon, GA:<br />

Mercer University Press, 1985), 179<strong>–</strong>210.<br />

19 Ralphson was the alias <strong>of</strong> Jeremiah Mardsen. For biographical<br />

details on Ralphson, see R.L. Greaves, “Marsden,<br />

(alias Ralphson), Jeremiah (1624<strong>–</strong>1684),” in Biographical<br />

Dictionary <strong>of</strong> British Radicals, eds. Richard L. Greaves and<br />

Robert Zaller (Brighton, England: Harvester Press, 1984),<br />

2:214<strong>–</strong>215.<br />