english - Museo Nacional de Escultura

english - Museo Nacional de Escultura

english - Museo Nacional de Escultura

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

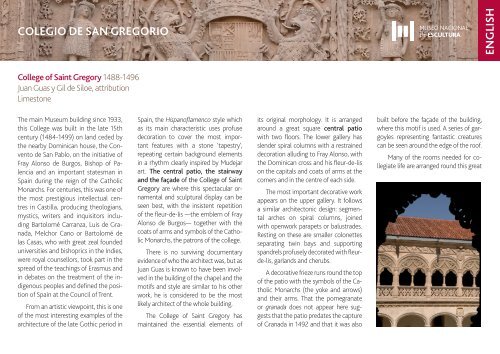

Colegio <strong>de</strong> San gregorio<br />

College of Saint Gregory 1488-1496<br />

Juan Guas y Gil <strong>de</strong> Siloe, attribution<br />

Limestone<br />

The main Museum building since 1933,<br />

this College was built in the late 15th<br />

century (1484-1499) on land ce<strong>de</strong>d by<br />

the nearby Dominican house, the Convento<br />

<strong>de</strong> San Pablo, on the initiative of<br />

Fray Alonso <strong>de</strong> Burgos, Bishop of Palencia<br />

and an important statesman in<br />

Spain during the reign of the Catholic<br />

Monarchs. For centuries, this was one of<br />

the most prestigious intellectual centres<br />

in Castilla, producing theologians,<br />

mystics, writers and inquisitors including<br />

Bartolomé Carranza, Luis <strong>de</strong> Granada,<br />

Melchor Cano or Bartolomé <strong>de</strong><br />

las Casas, who with great zeal foun<strong>de</strong>d<br />

universities and bishoprics in the Indies,<br />

were royal counsellors, took part in the<br />

spread of the teachings of Erasmus and<br />

in <strong>de</strong>bates on the treatment of the indigenous<br />

peoples and <strong>de</strong>fined the position<br />

of Spain at the Council of Trent.<br />

From an artistic viewpoint, this is one<br />

of the most interesting examples of the<br />

architecture of the late Gothic period in<br />

Spain, the Hispanoflamenco style which<br />

as its main characteristic uses profuse<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration to cover the most important<br />

features with a stone ‘tapestry’,<br />

repeating certain background elements<br />

in a rhythm clearly inspired by Mu<strong>de</strong>jar<br />

art. The central patio, the stairway<br />

and the faça<strong>de</strong> of the College of Saint<br />

Gregory are where this spectacular ornamental<br />

and sculptural display can be<br />

seen best, with the insistent repetition<br />

of the fleur-<strong>de</strong>-lis —the emblem of Fray<br />

Alonso <strong>de</strong> Burgos— together with the<br />

coats of arms and symbols of the Catholic<br />

Monarchs, the patrons of the college.<br />

There is no surviving documentary<br />

evi<strong>de</strong>nce of who the architect was, but as<br />

Juan Guas is known to have been involved<br />

in the building of the chapel and the<br />

motifs and style are similar to his other<br />

work, he is consi<strong>de</strong>red to be the most<br />

likely architect of the whole building.<br />

The College of Saint Gregory has<br />

maintained the essential elements of<br />

its original morphology. It is arranged<br />

around a great square central patio<br />

with two floors. The lower gallery has<br />

slen<strong>de</strong>r spiral columns with a restrained<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration alluding to Fray Alonso, with<br />

the Dominican cross and his fleur-<strong>de</strong>-lis<br />

on the capitals and coats of arms at the<br />

corners and in the centre of each si<strong>de</strong>.<br />

The most important <strong>de</strong>corative work<br />

appears on the upper gallery. It follows<br />

a similar architectonic <strong>de</strong>sign: segmental<br />

arches on spiral columns, joined<br />

with openwork parapets or balustra<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

Resting on these are smaller colonettes<br />

separating twin bays and supporting<br />

spandrels profusely <strong>de</strong>corated with fleur<strong>de</strong>-lis,<br />

garlands and cherubs.<br />

A <strong>de</strong>corative frieze runs round the top<br />

of the patio with the symbols of the Catholic<br />

Monarchs (the yoke and arrows)<br />

and their arms. That the pomegranate<br />

or granada does not appear here suggests<br />

that the patio predates the capture<br />

of Granada in 1492 and that it was also<br />

built before the faça<strong>de</strong> of the building,<br />

where this motif is used. A series of gargoyles<br />

representing fantastic creatures<br />

can be seen around the edge of the roof.<br />

Many of the rooms nee<strong>de</strong>d for collegiate<br />

life are arranged round this great<br />

engliSH

central patio. Today it is still possible to<br />

judge the importance of the use of each<br />

space by the sculptural <strong>de</strong>tail on the doorways;<br />

the most richly <strong>de</strong>corated lead<br />

into community areas such as the lecture<br />

rooms, the library, the Chapter house<br />

or the refectory; the <strong>de</strong>coration is more<br />

restrained or almost non-existent on the<br />

doors to the cells or rooms of the individual<br />

members of the community.<br />

The walls of the magnificent staircase<br />

which joins the two floors of the<br />

central patio are covered with a rich<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration which brings together the<br />

three artistic trends which coexisted<br />

at the time in Spain: gothic tracery<br />

on the balustra<strong>de</strong> and lower part of<br />

the walls, Renaissance rusticated stonework<br />

on the walls and a Mu<strong>de</strong>jar<br />

artesonado ceiling.<br />

The faça<strong>de</strong> of the College has a unique<br />

place in the architectonic sculpture<br />

of Spain and has been the object of<br />

attention ever since it was built. Designed<br />

in sections like a retable, it is<br />

completely covered with a stonework<br />

tapestry of plant and foliage motifs<br />

(tied bundles of branches, plaited willow,<br />

thistle leaves) and heraldic motifs<br />

(the fleur-<strong>de</strong>-lis, emblem of Fray Alonso<br />

<strong>de</strong> Burgos), encapsulating a complete<br />

iconographic programme <strong>de</strong>dicated<br />

to the greater glory of the foun<strong>de</strong>r and<br />

of its patrons the Catholic Monarchs.<br />

A great arch frames the lintel of the<br />

doorway forming a tympanum with a<br />

symbolic representation of the foundation<br />

of the College: Fray Alonso <strong>de</strong><br />

Burgos is shown kneeling to offer the<br />

building to Pope St Gregory, in the presence<br />

of St Dominic, the foun<strong>de</strong>r of<br />

the Dominican Or<strong>de</strong>r which the Bishop<br />

belonged to and of St Paul (the patron<br />

saint of the nearby convent).<br />

The upper part of the faça<strong>de</strong> is taken<br />

up with a fountain with a pomegranate<br />

tree emerging from it, possibly representing<br />

the Fountain of Life and Tree<br />

of Knowledge, symbols of the Paradise<br />

to which Man can only return through<br />

knowledge. The great coat of arms of<br />

the Catholic Monarchs imbues the whole<br />

monumental faça<strong>de</strong> with a triumphal<br />

exaltation of the monarchy. The magnificent<br />

stone retable is completed with<br />

two strong piers carved with warriors<br />

and savages, the former a symbol of virtue<br />

and the latter as guards of honour,<br />

both protecting the central emblem.<br />

The name of Gil <strong>de</strong> Siloe, often mentioned<br />

as the possible artist of the faça<strong>de</strong><br />

is certainly the most likely of all those<br />

who have been suggested, both for the<br />

style and the originality of the <strong>de</strong>sign.<br />

Please leave this information<br />

sheet in the stand in the patio.<br />

engliSH

Coffered Ceilings<br />

The building of the College of Saint<br />

Gregory must have begun at the end of<br />

1487 and although the first members<br />

of the College were already admitted<br />

by 1496, work continued in the early<br />

years of the 16 th century. This monumental<br />

complex, profusely <strong>de</strong>corated<br />

according to the fashion of the time,<br />

was immediately acclaimed with enthusiasm<br />

by its contemporaries. The<br />

architecture and its rooms with their<br />

unending succession of gil<strong>de</strong>d and polychrome<br />

ceilings worked with splendid<br />

craftsmanship, led the Portuguese traveller<br />

Pinheiro da Veiga to <strong>de</strong>scribe it in<br />

1605 as ‘a gol<strong>de</strong>n jewel and the most<br />

exquisite piece most finely finished of<br />

its size I have ever seen.’<br />

The building was well conserved until<br />

the Desamortización in 1835, when<br />

the property of the Church was confiscated<br />

and from then on it suffered<br />

from inappropriate uses as a prison, a<br />

barracks and offices. This, combined<br />

with the prevailing poverty of the time,<br />

led to some of the great rooms being<br />

<strong>de</strong>molished and the disappearance of<br />

several of the coffered ceilings, including<br />

those from the College library or<br />

the sumptuous corridor which links the<br />

entrance courtyard with the chapel.<br />

This process of <strong>de</strong>terioration was<br />

halted when the building was <strong>de</strong>clared<br />

a national monument in 1884 and the<br />

complete restoration was begun of the<br />

patio and much of the rest of the building<br />

in the years that followed; even so,<br />

in some areas such as the cloister or the<br />

small entrance patio, the roof beams<br />

had to be completely replaced because<br />

they were in such bad condition,<br />

although the original <strong>de</strong>coration was<br />

reproduced.<br />

The installation of the Museum in<br />

the building in 1933 reinforced further<br />

the exceptional character of what had<br />

been conserved and led to a continuing<br />

policy to restore the whole building<br />

with the installation of several ceilings<br />

from other buildings which were <strong>de</strong>molished<br />

during the second half of the<br />

20th century, in Valladolid itself and in<br />

other parts of Spain.<br />

Along the route of the permanent<br />

exhibition, the ceilings of particular interest<br />

belonging originally to the College<br />

are mentioned below:<br />

Room 1: the Renaissance-style <strong>de</strong>corated<br />

woo<strong>de</strong>n panelled ceiling or<br />

alfarje has 24 large beams resting on<br />

corbels, with polychrome lions and<br />

the fleur-<strong>de</strong>-lis of the arms of Fray<br />

Alonso <strong>de</strong> Burgos, with carved and<br />

gil<strong>de</strong>d bosses and mocárabes – <strong>de</strong>corative<br />

motifs resembling stalactites.<br />

In both Room 3 and Room 4 the alfarjes<br />

are Renaissance in style, ma<strong>de</strong> of<br />

great beams with polychrome caissons,<br />

although the one in Room 4 is not so<br />

well preserved. Both these ceilings are<br />

<strong>de</strong>corated with angels’ heads, sphinxes,<br />

garlands, fruit and other Renaissance<br />

motifs, with the coat of arms of Fray<br />

Alonso <strong>de</strong> Burgos prominently displayed<br />

on the roof boards.<br />

Rooms 6 and 8 on the upper floor<br />

have two magnificent artesonados which<br />

together with another even larger one<br />

which disappeared in the 19 th century,<br />

formed the ceilings of the library. The<br />

two which have survived are ochavos (on<br />

an octagonal plan) resting on squinches<br />

<strong>de</strong>corated with the coat of arms of the<br />

foun<strong>de</strong>r, although some are partly missing.<br />

They have a Renaissance <strong>de</strong>coration<br />

on the friezes and a large cone of mocarabes<br />

in the centre. The ceiling in Room<br />

6 is <strong>de</strong>corated with gil<strong>de</strong>d caissons and<br />

bosses and the <strong>de</strong>coration in Room 8 is<br />

Mu<strong>de</strong>jar-inspired knotwork.<br />

englisH

Continuing through the permanent<br />

exhibition, the ceilings installed in the<br />

Museum from 1935 onwards inclu<strong>de</strong><br />

the following interesting examples:<br />

In the Rest Area, between Rooms<br />

14 and 15, there is a large choir gallery<br />

with a Renaissance coffered ceiling,<br />

dating from 1540 and acquired by the<br />

State in 1962, which was originally in<br />

the church of San Vicente <strong>de</strong> Villar <strong>de</strong><br />

Fallaves (Zamora). Ma<strong>de</strong> of pine with<br />

no polychromy, it is <strong>de</strong>signed as threesi<strong>de</strong>d<br />

with two large triangles at the<br />

front, and the whole surface is covered<br />

with hexagons and octagons, finishing<br />

in a rail with slen<strong>de</strong>r balusters.<br />

Eight medallions show warriors and<br />

female figures and three have the Maltese<br />

Cross, as the church belonged to<br />

the Or<strong>de</strong>r of the Knights of Malta.<br />

The flat ceiling in Room 15 is carved<br />

wood, painted white with gil<strong>de</strong>d<br />

<strong>de</strong>tails, acquired in 1935. Dated c. 1752,<br />

it came from the Palacio <strong>de</strong>l Marqués<br />

<strong>de</strong> Monsalud in Almendralejo (Badajoz).<br />

With Portuguese influence, it has<br />

profuse sculptural <strong>de</strong>coration mixed<br />

with plant and mythological motifs: a<br />

gol<strong>de</strong>n sun is surroun<strong>de</strong>d by abundant<br />

foliage and birds, with the figures of<br />

Eros and Mercury and the chariots of<br />

the four winds - Boreas (N), Euros (E),<br />

Notos (S) and Zephyros (W) according<br />

to Greek mythology.<br />

In Room 16 there is a coffered ceiling<br />

which was the roof of the former<br />

church of el Rosario, reconstructed in<br />

1535 when it was incorporated into<br />

the royal chapel of the Palacio Real <strong>de</strong><br />

Valladolid. Demolished in 1952, this<br />

ceiling was installed as part of the Museum.<br />

In the Mudéjar tradition it combines<br />

Muslim inspired <strong>de</strong>corations with<br />

Renaissance elements, all finished off<br />

with a cluster of mocárabes.<br />

Room 17 has a Renaissance coffered<br />

ceiling ma<strong>de</strong> of pine with a plant motif<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration from the mid 16th century.<br />

Acquired on the art market in 1969, it<br />

must have <strong>de</strong>corated a now <strong>de</strong>molished<br />

palace.<br />

Installed in Room 18 there is part<br />

of the panelled ceiling or alfarje of the<br />

cloister of the Monasterio <strong>de</strong> San Quirce<br />

in Valladolid. This was <strong>de</strong>signed between<br />

1620-25 by Francisco <strong>de</strong> Praves, the Royal<br />

architect. It was <strong>de</strong>molished in 1965<br />

and part was acquired by the museum;<br />

its simple structure, appropriate to a<br />

classicist patio, is composed of beams<br />

resting on corbels and caissons with little<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration.<br />

In Room 19 there is an octagonal coffered<br />

ceiling resting on squinches in Mu<strong>de</strong>jar<br />

style with a <strong>de</strong>coration of knotwork<br />

and two clusters of mocárabes, dated c.<br />

1522. This is from the former Hospital <strong>de</strong><br />

San Nicolás <strong>de</strong> Olmedo (Valladolid). Taken<br />

down in 1962, it was acquired by the Museum<br />

two years later.<br />

In Room 20 there is another octagonal<br />

coffered ceiling in the Mu<strong>de</strong>jar tradition<br />

<strong>de</strong>corated with knotwork and clusters<br />

of mocárabes, dated around 1530<br />

and largely reconstructed. This comes<br />

from the transept of the church of San<br />

Nicolás <strong>de</strong> Castrover<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> Campos (Zamora)<br />

and fortunately survived the for-<br />

tuitous collapse of the building in 1970,<br />

and was then acquired by the Museum<br />

in 1974.<br />

This exceptional group is completed<br />

with the monumental coffered ceiling,<br />

originally part of this building, which<br />

roofs the staircase of the patio. This<br />

octagonal ceiling, <strong>de</strong>corated with knotwork<br />

and three great clusters of mocárabes,<br />

was restored in 1860 as all its<br />

original polychromy had disappeared. It<br />

is outstanding for the <strong>de</strong>coration of the<br />

lower frieze or arrocabe with the initials<br />

F and Y of the Catholic Monarchs along<br />

with other floral motifs.<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in the entrance hall at<br />

the end of your visit.<br />

englisH

ROOMS 1 and 2. A TIME OF GREAT CHANGE<br />

Pietà around 1406-1415<br />

Germanic<br />

Polychrome stone<br />

The sculptural theme of the Pietá was<br />

wi<strong>de</strong>ly used in the Germanic countries<br />

from 1400 and originated in the <strong>de</strong>votion<br />

to the Virgin Mary during the liturgy<br />

of Holy Thursday. The mourning mother<br />

with her <strong>de</strong>ad son, removed from<br />

any spatial-temporal context, is the<br />

favoured support for meditation on the<br />

<strong>de</strong>ath of Jesus, inspired by the literature<br />

of the mystics. From then on it was to<br />

become a favourite and recurrent theme<br />

in art.<br />

The genre of this sculpture is known<br />

as the ‘beautiful Madonnas’, elegant<br />

figures with <strong>de</strong>licate, intensely expressive<br />

faces, dressed in robes falling in<br />

many folds with <strong>de</strong>corative rhythmic<br />

curves used to imply a refined movement<br />

of the mother’s body in tragic<br />

contrast to the static immobility of<br />

the son. This sculpture represents the<br />

Virgin Mary as a ten<strong>de</strong>r young woman,<br />

weeping in fear, hardly able to support<br />

the rigor mortis of the large naked body<br />

laid across her lap.<br />

This sculpture is of central European<br />

provenance and is from the chapel of<br />

the Bishop of Palencia, Sancho <strong>de</strong> Rojas,<br />

in the cloister of the Monasterio <strong>de</strong> San<br />

Benito el Real in Valladolid. (Room 1)<br />

Retable of Saint Jerome around 1465<br />

Jorge Inglés<br />

Oil on panel<br />

This retable of St Jerome was commissioned<br />

by Alonso <strong>de</strong> Fonseca, the<br />

Archbishop of Seville and member of<br />

an influential family of the Kingdom of<br />

Castile, represented in this work by the<br />

coat of arms. This is one of the finest<br />

examples of the wi<strong>de</strong>r international<br />

context of art in Castile at this time as<br />

the artist, who was from northern Europe<br />

and familiar with Flemish painting,<br />

worked for the marqués <strong>de</strong> Santillana.<br />

Beneath the structure of gothic canopies,<br />

scenes from the life of the great<br />

translator of the Bible are shown in a<br />

narrative sequence of the main events,<br />

with anecdotes and <strong>de</strong>tails. The central<br />

scene shows the scholarly Saint writing<br />

amid the tools of his tra<strong>de</strong>, accompanied<br />

by the lion, which appears in some<br />

episo<strong>de</strong>s of the legend of the saint and<br />

is one of his characteristic symbols. On<br />

the pre<strong>de</strong>lla, the figures of Christ as<br />

Man of Sorrows, the Virgin and St John<br />

are shown flanked by various saints.<br />

The work is characterized by its naturalism<br />

and the tragic, concentrated<br />

realism of the characters. The extraordinary<br />

mastery of the drawing is enhanced<br />

by the fascination for the variety<br />

and material quality of the objects,<br />

the stiff angular folds and the search<br />

for <strong>de</strong>pth and perspective in the chequered<br />

floors and the inclusion of the<br />

landscape. (Room 1)<br />

ENGLISH

Retable of the life of the Virgin around 1515-1520<br />

Brabant, Antwerp?<br />

Walnut<br />

This altarpiece reveals the export of<br />

Flemish carvings to Castile, where they<br />

were highly thought of. The box-shaped<br />

structure with curved edges i<strong>de</strong>ntifies<br />

it as work produced in the city of Antwerp<br />

around 1515.<br />

Carved in walnut, the retable is divi<strong>de</strong>d<br />

into three panels, separated by<br />

Gothic columns, showing five scenes<br />

from the life of the Virgin, or<strong>de</strong>red<br />

chronologically from left to right and<br />

top to bottom. the Birth of the Virgin,<br />

the Annunciation, the Birth of Jesus,<br />

the Adoration of the Three Kings and, in<br />

the centre, the Descent from the Cross.<br />

In the lower part this shows the Mourning<br />

of Christ and above, an incomplete<br />

Calvary scene, outlined against the<br />

background of Jerusalem <strong>de</strong>picted as a<br />

contemporary Flemish city. The reliefs<br />

rest on ledges adorned with plant motifs<br />

with openwork canopies above. The<br />

altarpiece was originally a triptych with<br />

two doors.<br />

A <strong>de</strong>tailed analysis of the scenes<br />

allows the hand of different artists to<br />

be distinguished, evi<strong>de</strong>nce of the usual<br />

creative process, where different artists<br />

would work to the or<strong>de</strong>rs of the master<br />

craftsman. The upper parts of the two<br />

si<strong>de</strong> panels are outstanding in their <strong>de</strong>licate<br />

composition and exquisitely <strong>de</strong>tailed<br />

execution; the rest present greater<br />

volumetric and expressive force and<br />

marked realism in the characterization.<br />

The whole transmits abundant information<br />

on the age in which it was<br />

ma<strong>de</strong>. The <strong>de</strong>votio mo<strong>de</strong>rna, a religious<br />

movement active in the 15 th century<br />

which encouraged a more intimate<br />

relationship with beliefs, tinged the religious<br />

with the everyday, bringing the<br />

sacred up to the present day. (Room 1)<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in Room 1.<br />

The Holy Kindred around 1510<br />

Swabia or Franconia<br />

Wood with traces of polychromy<br />

In Spain, the most common representation<br />

of St Anne in the late Middle<br />

Ages was in a group of three. mother,<br />

daughter and grandson, but in the north<br />

of Europe the apocryphal legend of<br />

the triple marriage became very popular.<br />

According to this version the mother<br />

of the Virgin, after the <strong>de</strong>ath of St<br />

Joachim, remarried twice more, with<br />

Salomé and Cleophas. Her <strong>de</strong>scendants<br />

and exten<strong>de</strong>d family inclu<strong>de</strong>d up<br />

to twenty five characters —daughters,<br />

sons-in-law and grandchildren. In the<br />

thematic purge of the Council of Trent<br />

this version was con<strong>de</strong>mned and the<br />

doctrine reinstated of the chastity of<br />

St Anne. This relief shows a reduced<br />

version of the genealogy, in a representation<br />

of the three main figures with St<br />

Joseph and the successive husbands of<br />

St Anne.<br />

This is a fine example of the quality<br />

attained by many workshops in the<br />

south of Germany at the end of the<br />

15 th century and early 16 th century. The<br />

unfortunate loss of much of the polychromy<br />

allows an appreciation of the<br />

<strong>de</strong>tail of the work. the wrinkled faces,<br />

<strong>de</strong>tailed hair and the veins un<strong>de</strong>r the<br />

skin of the masculine figures. (Room 2)<br />

ENGLISH

ROOMS 3, 4 and 5. THE STYLE OF ALONSO BERRUGUETE<br />

Saint Sebastian<br />

Great retable of San Benito el Real 1526-1532<br />

Alonso Berruguete. Polychrome wood<br />

Although this Saint was often represented<br />

in the Middle Ages dressed as<br />

a knight with bow and arrows, from<br />

the quattrocento onwards the image<br />

was used of the first martyr, allowing<br />

the Renaissance artists to convert the<br />

Saint into an emblematic nu<strong>de</strong> masculine<br />

figure. This can be seen here in<br />

this sculpture with the adolescent body<br />

tensed from the intense pain, bound to<br />

the curved trunk to receive the impact<br />

of the arrows, in an agitated writhing<br />

rhythm; even the gol<strong>de</strong>n locks of hair<br />

fall forward, following the same rhythm.<br />

Although the mouth is half open the<br />

facial expression is melancholic, rather<br />

than agonised. The loin cloth is ma<strong>de</strong> of<br />

fabric and stuck onto the sculpture.<br />

Berruguete’s treatment of volume<br />

can be clearly seen in this sculpture,<br />

giving the impression of movement by<br />

breaking the equilibrium and the i<strong>de</strong>a<br />

of frontality by displacing the legs and<br />

arms in opposite directions, disjointing<br />

the figure. (Room 3)<br />

The Adoration of the Magi<br />

Great retable of San Benito el Real 1526-1532<br />

Alonso Berruguete. Polychrome wood<br />

This is one of the most beautiful reliefs<br />

of this altarpiece. The scene is arranged<br />

below a scallop shell as portal. The elegantly<br />

serene figure of the Virgin centres<br />

the composition, adorned with a classical<br />

headdress, and holding on her lap a<br />

sturdy Baby Jesus displaying his sexuality<br />

as the sign of his human condition.<br />

Following the medieval symbolism,<br />

both these figures are proportionally<br />

larger to emphasize their hierarchical<br />

importance. On the left, the figure of<br />

St Joseph, with his calm attitu<strong>de</strong> tinged<br />

with gran<strong>de</strong>ur, is the counterpoint to<br />

the impulse which pushes the Magi to<br />

their agitated adoration.<br />

The <strong>de</strong>nsity of the figures in a very<br />

small space, forcing their positions and<br />

the predominance of the figures over<br />

the space distances this work from<br />

the Renaissance principles and places<br />

it within the Mannerist movement.<br />

Chromatically warm tones are used,<br />

with gold and ochres and the rosy<br />

flesh colours of the ‘encarnado’. The fi-<br />

gures are outlined against the rich polychromy<br />

of the un<strong>de</strong>rlying gold of the<br />

estofado and the background of the<br />

relief. The estofado technique uses a<br />

background of gold leaf applied to the<br />

sculpture, which is then covered with<br />

polychromy and scored with <strong>de</strong>corative<br />

patterns to allow the gold to show<br />

through. (Room 3)<br />

ENGLISH

Saint Mark and St Matthew, Evangelists<br />

Great retable of San Benito el Real 1526-1532<br />

Alonso Berruguete. Grisaille on panel<br />

Consi<strong>de</strong>red as the pillars of the New<br />

Law, the authors of the Gospels are<br />

often represented on 16 th century altarpieces<br />

as an allegory of the doctrinal<br />

basis of the narrative sequences<br />

contained in them. The retable of San<br />

Benito inclu<strong>de</strong>s two paintings on board,<br />

showing St Mark and St Matthew writing<br />

the sacred texts.<br />

Here the grisaille technique is used<br />

for these figures, painted using white,<br />

black and a range of greys imitating<br />

relief, giving an effect of sculpture by<br />

applying the colour on large edged pla-<br />

nes. Depicted in an ethereal space, the<br />

silhouettes are outlined against a gold<br />

background reminiscent of an unfinished<br />

mosaic, with classicist echoes learned<br />

in Italy in a magnificent adaptation<br />

of the medieval tradition to the Renaissance<br />

aesthetic.<br />

An apparently distracted St Mark<br />

strokes the head of the lion, his symbol,<br />

while a beautiful female figure illuminates<br />

him in his task as chronicler. St<br />

Matthew is shown working on his text<br />

with the help of a young boy posing as<br />

his easel. (Room 4)<br />

Sacrifice of Isaac<br />

Great retable of San Benito el Real 1526-1532<br />

Alonso Berruguete. Polychrome wood<br />

This subject was chosen by Signoria in<br />

Florence in 1402 for the doors of the<br />

Baptistery and then became wi<strong>de</strong>ly<br />

used. God required Abraham, the patriarch<br />

of the Israelites, to sacrifice his<br />

son to <strong>de</strong>monstrate his faith. Abraham,<br />

captured here at the moment when<br />

he is just about to make the sacrifice<br />

to obey the divine command, is one of<br />

the most personal creations of Berruguete.<br />

This is the perfect image of <strong>de</strong>speration,<br />

with every <strong>de</strong>tail proclaiming<br />

his dramatic situation. At his feet Isaac,<br />

loosely bound and unresisting, seems<br />

to accept his fate.<br />

This work presents a dynamic structure<br />

and an extraordinary plastic power<br />

shown in multiple points of view but<br />

which do not reduce the cohesion of<br />

the group. The contrast of the circular<br />

disposition of Isaac which reflects his<br />

submission, and the ascending, supplicant<br />

stretching of Abraham, manages<br />

to exteriorize his violent tension reinforced<br />

by <strong>de</strong>tails as apparently insig-<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in Room 5.<br />

nificant as the sharply pointed beard<br />

which seems to pierce the patriarch’s<br />

breast. (Room 5)<br />

ENGLISH

ROOMS 6 and 7. ARTISTIC VARIETY IN THE 16 th CENTURY<br />

Adoration of the Shepherds first third of the 16 th century<br />

Gabriel Joly, attribution<br />

Natural wood<br />

Just two scenes form the subject of this<br />

small retable or altarpiece ma<strong>de</strong> for the<br />

private chapel of the Prior of the Monasterio<br />

<strong>de</strong> la Mejorada <strong>de</strong> Olmedo:<br />

the Adoration of the Shepherds on the<br />

main panel and above it the Crucifixion.<br />

Around the edge of the crowning piece<br />

can still be seen the figures of two putti<br />

holding a garland and the remains of the<br />

more complex ornamental composition<br />

which completed the altarpiece.<br />

The two reliefs show a naturalist<br />

approach with an exquisite attention to<br />

<strong>de</strong>tail. The Adoration of the Shepherds<br />

is represented as an outdoor scene with<br />

a foreground composition of figures divi<strong>de</strong>d<br />

into two groups around the small<br />

figure of the Infant Jesus. A background<br />

scene of imaginary architecture and irregular<br />

perspective leads into a third level<br />

showing the angel appearing to the she-<br />

pherds, with the figures becoming smaller<br />

in size and the sculptural workmanship<br />

<strong>de</strong>monstrating extraordinary skill.<br />

(Room 6)<br />

Bust of the Emperor Charles V around 1520<br />

Anonymous, Flemish<br />

Limestone<br />

The importance the House of Austria<br />

gave to the official image of its members<br />

is shown in this very early portrait<br />

of the future Emperor Charles V with<br />

his long face, jutting jaw and hanging<br />

lower lip, wearing a hat with large plumes<br />

and the collar of the Or<strong>de</strong>r of the<br />

Gol<strong>de</strong>n Fleece. The bust may date from<br />

around 1520, close to the time of his<br />

coronation in Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle)<br />

and represents an immature face,<br />

still lacking the energy and power of<br />

the mature portraits of the Emperor.<br />

Two similar portraits can be seen in<br />

museums in Bruges and Ghent. Pietro<br />

Torrigiano may have introduced the<br />

typology of the Florentine bust into<br />

central Europe, although the formal<br />

language of Flan<strong>de</strong>rs is still used, the<br />

same as can be seen in the religious<br />

works in Rooms 1 and 2, but used here<br />

to highlight the political importance of<br />

the subject. (Room 7)<br />

ENGLISH

Choir stalls from San Benito el Real 1525-1529<br />

Andrés <strong>de</strong> Nájera and others<br />

Natural and polychrome wood<br />

At the beginning of the 16 th century the<br />

Catholic Monarchs pressed for a reform<br />

to reorganize the Benedictine Or<strong>de</strong>r in<br />

Spain and create a Congregation which<br />

grouped together its religious houses<br />

in the Kingdom of Castile and some<br />

of those in Aragon. The centre was the<br />

Benedictine Monasterio <strong>de</strong> San Benito<br />

el Real <strong>de</strong> Valladolid where the abbots<br />

from the different houses met at regular<br />

intervals to discuss monastic matters.<br />

Precisely for these meetings, as well<br />

as for the liturgy of the Benedictine<br />

community in Valladolid, it was agreed<br />

that a set of choir stalls should be ma<strong>de</strong><br />

and that the abbot of each monastery<br />

would have his own seat in the upper<br />

row, <strong>de</strong>pending on the date when he<br />

entered the Congregation.<br />

The choir stalls have forty places.<br />

Thirty four correspond to each of the<br />

monasteries in the Congregation with<br />

the remaining six for its benefactors.<br />

Each stall in the upper row has the<br />

name of the monastery on the back,<br />

the name of its patron saint, foun<strong>de</strong>r<br />

and religious or lay person related to<br />

it on the seat, and on the cresting, the<br />

arms of the monastery or of its foun<strong>de</strong>r,<br />

carved with polychromy, between small<br />

carved statues. The only polychrome<br />

seat corresponds to the Abbot of the<br />

Monasterio <strong>de</strong> San Benito <strong>de</strong> Valladolid<br />

itself, emphasizing that this was the<br />

most important monastery of all.<br />

The backs of the twenty six stalls<br />

in the lower row represent a narrative<br />

sequence of the life of Christ and of<br />

the Virgin and some specific <strong>de</strong>votions<br />

from the lives of the saints. At the ends,<br />

on either si<strong>de</strong> of the central aisle, the<br />

two royal couples —the Catholic monarchs<br />

and Charles V and Isabel of Portugal—<br />

proclaim the royal protection<br />

for the Benedictine Congregation and<br />

their close links with it.<br />

There is very little surviving documentation<br />

referring to these choir stalls,<br />

but the agreement is known by which<br />

each abbey promised to pay the cost of<br />

an upper and a lower seat, to help with<br />

the costly commission to be carried out<br />

by a team of craftsmen. The formal similarities<br />

of the compositional <strong>de</strong>sign<br />

and <strong>de</strong>coration with the choir stalls in<br />

the Cathedral in Santo Domingo <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Calzada have i<strong>de</strong>ntified the master craftsman<br />

Andrés <strong>de</strong> Nájera as the probable<br />

mastermind of the whole work.<br />

The group of artists who took part in<br />

the carving of the choir stalls inclu<strong>de</strong> the<br />

sculptor Guillén <strong>de</strong> Holanda, and others<br />

linked with workshops in Avila. Among<br />

the different reliefs, the seat back corresponding<br />

to the Monasterio <strong>de</strong> San<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Burgos stands out for the quality<br />

of its representation of St John the<br />

Baptist and from the beginning was at-<br />

tributed to Diego <strong>de</strong> Siloe, because of its<br />

relationship with the Italian mo<strong>de</strong>ls, its<br />

mastery of the anatomy and the elegance<br />

of the gestures.<br />

The lower and upper stalls present<br />

an exquisite and varied ornamentation<br />

mostly ma<strong>de</strong> up of grotesques and other<br />

renaissance motifs, carved or inlaid on<br />

the seat backs. (Room 7)<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in Room 8.<br />

ENGLISH

ROOM 8. THE DRAMATISM OF JUAN DE JUNI<br />

The Burial of Christ around 1540<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Juni<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

The group of figures in The Burial of<br />

Christ was created by Juan <strong>de</strong> Juni for<br />

Fray Antonio <strong>de</strong> Guevara, the illustrious<br />

Franciscan, chronicler of the Emperor<br />

Charles V and Bishop of Mondoñedo<br />

and was originally in his funerary chapel<br />

in the former Convento <strong>de</strong> San Francisco<br />

in Valladolid. According to <strong>de</strong>scriptions<br />

which have survived, the group<br />

was in the centre of a plasterwork altarpiece.<br />

This structure and the figures<br />

of two soldiers which guar<strong>de</strong>d the scene<br />

disappeared when the convent was<br />

<strong>de</strong>molished.<br />

This scenographic representation<br />

of the Burial of Christ is <strong>de</strong>signed to<br />

be viewed from the front. There are<br />

seven figures: the main figure of the<br />

<strong>de</strong>ad Christ articulates the arrangement<br />

of the other six who are distributed<br />

symmetrically about an imaginary<br />

axis passing between the Virgin and<br />

St John, following a completely classical<br />

<strong>de</strong>sign. Each figure has a counter-<br />

part on the other si<strong>de</strong> of the group with<br />

a similar movement and attitu<strong>de</strong>, and<br />

their kneeling or standing positions are<br />

conditioned by the frontal view of the<br />

whole group.<br />

The figure of Christ rests on a sarcophagus<br />

with the coat of arms of Fray<br />

Antonio <strong>de</strong> Guevara. The polychromy<br />

of the majestic body and head, with<br />

the violet tones of the bruises and blackish<br />

dried blood, suggests long drawn<br />

out suffering and with the broken and<br />

disjointed hands is what transmits<br />

most expressively the horror of <strong>de</strong>ath.<br />

The other figures show their reactions<br />

to the corpse: the Virgin, inconsolable,<br />

stretches out her arms to her<br />

Son, gently held back and supported<br />

by St John. On the left, Salomé and<br />

Joseph of Arimathea (appealing to the<br />

onlooker to take an active part in the<br />

scene) show the effect of their <strong>de</strong>ep<br />

physical and moral suffering in their<br />

strained faces, worn and dull. On the<br />

right, Mary Magdalene, the most <strong>de</strong>licate<br />

figure in the group, transmits<br />

her sorrow with a whirling movement<br />

reflected in her flowing garments, while<br />

Nico<strong>de</strong>mus raises his eyes to heaven<br />

in agonised supplication. They are all<br />

involved in the tragic task of laying<br />

out the body: removing the thorns,<br />

cleaning the wounds, perfuming it for<br />

burial, as shown by the objects they<br />

are holding (jugs, cloths and jars of<br />

perfume).<br />

In the 17 th century the group was<br />

painted over, hiding the beautiful polychrome<br />

estofado. In 1978, a slow, laborious<br />

process restored the original<br />

appearance, leaving only the back of the<br />

figure of Nico<strong>de</strong>mus as evi<strong>de</strong>nce of how<br />

it had been painted. (Room 8)<br />

ENGLISH

Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint John the Baptist 1551-1570<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Juni and Juan Tomás <strong>de</strong> Celma<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

In 1551, Doña Francisca Villafañe commissioned<br />

the sculptor Juan <strong>de</strong> Juni and<br />

his disciple Inocencio Berruguete, to<br />

produce an altarpiece <strong>de</strong>dicated to St<br />

John the Baptist for her funerary chapel<br />

in the church of San Benito el Real <strong>de</strong><br />

Valladolid. This was where the sculptures<br />

of St John the Baptist and Mary<br />

Magdalene displayed in this room<br />

came from.<br />

These two figures can be consi<strong>de</strong>red<br />

as authentic masterpieces within<br />

the work of Juni; the wood is imbued<br />

with the full power of the artist and<br />

the sculptures are charged with enormous<br />

emotional force As is usual in<br />

this artist’s work, this is shown in their<br />

intense twisting movements, the full<br />

and intricately fol<strong>de</strong>d garments they<br />

are wrapped in and by the facial expressions<br />

—of rapture for St John and<br />

of mourning for Mary Magdalene.<br />

St John was the patron saint of the<br />

altarpiece and the figure which set the<br />

standard for the quality of the whole<br />

group. The arrangement and powerful<br />

anatomy of this figure is a complete<br />

catalogue of powerful lines, inevitably<br />

reminiscent of the Hellenistic sculpture<br />

of Laocoön and his sons. The saint<br />

is shown pointing with his in<strong>de</strong>x finger<br />

to the lamb as in the text Ecce Agnus<br />

Dei, and with the left hand holding<br />

part of the cross-shaped staff which<br />

is one of his attributes. The sculpture<br />

of Mary Magdalene, holding the base<br />

of the perfume jar, conveys all the<br />

courtesan’s beauty and sensual passion<br />

in her attitu<strong>de</strong>. (Room 8)<br />

San Antonio <strong>de</strong> Padua around 1560<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Juni<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Juni carved this statue of St Anthony<br />

of Padua for the funerary chapel of<br />

Francisco Salón <strong>de</strong> Miranda in the Convento<br />

<strong>de</strong> San Francisco <strong>de</strong> Valladolid. St<br />

Anthony was a Franciscan born in Lisbon,<br />

who died in Padua after an intense life<br />

<strong>de</strong>dicated to preaching.<br />

The iconographic episo<strong>de</strong> chosen by<br />

the artist to represent the saint corresponds<br />

to one of the most significant and<br />

popular scenes in the story of the saint’s<br />

life: the apparition of the Child Jesus on<br />

the book which the Franciscan used as<br />

the basis of his preaching on the mystery<br />

of the Incarnation, with the vision<br />

seeming to emanate from the text itself.<br />

The strange position of St Anthony,<br />

in an ascending spiral, with one foot on<br />

the ground and the other knee resting<br />

on the trunk of a tree, seems to capture<br />

the fleeting instant when he is both<br />

amazed at the apparition and trying<br />

to kneel in adoration. The attitu<strong>de</strong> of<br />

the child strangely echoes the position<br />

of the Saint, but facing in the opposite<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in Room 8.<br />

direction. The two figures gaze at each<br />

other intensely, converging in mystical<br />

communication.<br />

The polychromy of the sculpture with<br />

its polished encarnado for the flesh and<br />

complex estofado work on the roun<strong>de</strong>d<br />

folds of the habit, may have been modified<br />

in the 17 th century when the bor<strong>de</strong>r<br />

was painted with a fine brush and<br />

glass eyes were ad<strong>de</strong>d to the two figures.<br />

(Room 8)<br />

ENGLISH

ROOMS 10 – 13. ART UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF ROME<br />

The temptations of Saint Anthony the Abbot 1553-1559<br />

Diego Rodríguez and Leonardo <strong>de</strong> Carrión<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

These reliefs belong to the main altarpiece<br />

of the former church of the Hospital<br />

<strong>de</strong> San Antonio Abad in Valladolid.<br />

According to the ancient ecclesiastical<br />

tradition, St Anthony was a young<br />

Egyptian who retired to the <strong>de</strong>sert<br />

around the year 290 to practice fasting<br />

and penitence. Following his example<br />

during the following two centuries,<br />

groups of Christians abandoned normal<br />

life and there may have been as many<br />

as five thousand anchorites living in the<br />

wil<strong>de</strong>rnesses of the Nile. In the <strong>de</strong>lirium<br />

of his solitu<strong>de</strong>, St Anthony was tormented<br />

by <strong>de</strong>vils and their temptations, as<br />

shown in these two scenes with their<br />

magnificent polychromy.<br />

One relief shows the saint being<br />

beaten by a hor<strong>de</strong> of <strong>de</strong>vils to force him<br />

to sin. In the other he is assailed by lust,<br />

in the shape of an apparently respectable<br />

woman, but with a she-<strong>de</strong>vil’s horn.<br />

This legend arose out of the controversies<br />

in ancient Christian circles over<br />

permanent sexual renunciation. In the<br />

religious context, St Anthony embodies<br />

the melancholy temperament. In this<br />

state of mind the anchorite <strong>de</strong>bates<br />

between the discouragement caused by<br />

religious doubts and wicked thoughts,<br />

and the serenity of the contemplative<br />

life. (Room 10)<br />

Saint Onuphrius 1575- 1600<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Anchieta, attribution<br />

Alabaster<br />

The representation of hermit saints<br />

within the iconography of the late 16 th<br />

century respon<strong>de</strong>d to the <strong>de</strong>sire to<br />

emphasize the importance of penitence<br />

for the Catholic Church in contrast<br />

to its <strong>de</strong>nial by the Protestants. This led<br />

to the revival of some medieval <strong>de</strong>votions<br />

to hermits who had withdrawn to<br />

the solitu<strong>de</strong> of the forest or the <strong>de</strong>sert<br />

and who now became important again<br />

with the new values to be promoted.<br />

St Onophrius is one of these holy men,<br />

with the distinctive representation of<br />

his physiognomy taken from his legend,<br />

which <strong>de</strong>scribes how he covered<br />

his nakedness with his hair and beard<br />

which were never cut.<br />

This sculpture is similar to the style<br />

and mo<strong>de</strong>ls of the Romanist sculptor<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Anchieta. The alabaster figure<br />

is presented in a frontal pose, accentuating<br />

the strong anatomy and<br />

concealing the nudity with the <strong>de</strong>vice<br />

of the long hair. The imperative attitu<strong>de</strong>,<br />

the forceful gaze and the ges-<br />

ture of the hand on the beard evokes<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>ls in Italian statuary, particularly<br />

Michelangelo’s Moses, evi<strong>de</strong>ncing the<br />

unmistakeable origin of this new dignified<br />

and heroic artistic language, inten<strong>de</strong>d<br />

to represent and make wi<strong>de</strong>ly<br />

known the new principles and dogmas<br />

dictated by the Council of Trent.<br />

(Room 11)<br />

ENGLISH

Saint Peter Nolasco re<strong>de</strong>eming captives around 1599<br />

Pedro <strong>de</strong> la Cuadra<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

In spite of its mo<strong>de</strong>st plastic quality,<br />

this relief is interesting because of its<br />

high documentary value and its clearly<br />

intentional propaganda for the religious<br />

Or<strong>de</strong>r it refers to. The scene represents<br />

a frequent occurrence during<br />

the 16 th century: Christians taken captive<br />

by Barbary pirates from N. Africa<br />

or in battle being ransomed by monks<br />

of the Or<strong>de</strong>r of Mercedarians foun<strong>de</strong>d<br />

in the 13 th century by St Pedro Nolasco<br />

specifically for this mission.<br />

This work of Pedro <strong>de</strong> la Cuadra is<br />

interesting within the context of Valladolid<br />

at the time as it reflects the<br />

process of evolution of some of the<br />

contemporary sculptors from the col<strong>de</strong>r<br />

Romanist language to the baroque<br />

naturalism of Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z. This<br />

relief was part of the altarpiece of the<br />

Mercedarians chapel of the Convento<br />

<strong>de</strong> la Merced Calzada in Valladolid and<br />

belongs to the first of these periods.<br />

It is a good example of how this language<br />

became distorted into inelegant<br />

forms and solutions of lesser quality<br />

which only recovered with the expressive<br />

innovations introduced by Fernán<strong>de</strong>z.<br />

The figures of Pedro <strong>de</strong> la Cuadra<br />

are resolved with vigorous faces (with<br />

straight nose or bulging eyes) but at<br />

the same time they are repetitive and<br />

<strong>de</strong>personalized. The roun<strong>de</strong>d bodies<br />

and flowing robes, characteristic of<br />

Romanism, now show a heavy formalism<br />

which was not the case in earlier<br />

examples. (Room 12)<br />

The Annunciation of Mary 1596-1597<br />

Gregorio Martínez<br />

Oil on panel<br />

Consi<strong>de</strong>red a masterpiece of Gregorio<br />

Martínez, this was the central panel of<br />

the altarpiece commissioned by the<br />

banker Fabio Nelli for his funerary chapel<br />

in the church of San Agustín. It was originally<br />

completed with a pre<strong>de</strong>lla with<br />

four paintings related to the cycle of the<br />

childhood of Jesus and a crowning piece<br />

where the Trinity was represented. After<br />

the Desamortización, when the property<br />

of the religious houses was confiscated,<br />

only the central panel reached the<br />

Museum.<br />

The composition abandons the domestic<br />

intimacy of the Flemish Annunciations<br />

or the Quattrocento scenes<br />

from Florence and the Virgin’s cell is inva<strong>de</strong>d<br />

by the celestial world, with beams<br />

of brightness, diaphanous light and sha<strong>de</strong><br />

and a host of angels. The Holy Spirit,<br />

the spatial, luminous and symbolic centre<br />

of the scene, separates and links the<br />

earthly and the supernatural worlds. The<br />

example of the late Raphael is a <strong>de</strong>cisive<br />

influence here, as he led the way to the<br />

continuity between classicism and the<br />

new spirituality, when he marked out<br />

the change of direction from the humanist<br />

neo-Platonism (which harmonised<br />

interior meditation and worldliness)<br />

towards a violent irruption of the supernatural<br />

into human life: the Eternal<br />

hovers over earthly life in a new climate<br />

of visions and ecstasies. The <strong>de</strong>licate<br />

chromatic range, the value of chiaroscuro<br />

and the preference for loose folds are<br />

the outstanding traits in the painting by<br />

this artist. (Room 13)<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in Room 13.<br />

ENGLISH

VAL DEL OMAR, 20 th CENTURY MYSTIC<br />

Significance of Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar<br />

in the history of the Cinema<br />

and Art<br />

José Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar (Granada, 1904 – Madrid,<br />

1982) represents the link between<br />

the historic avant-gar<strong>de</strong> (led mainly by<br />

the cinema productions of Luis Buñuel<br />

and Salvador Dalí in the 1930s) and<br />

the mo<strong>de</strong>rn experimental cinema of<br />

the 1970s and 80s, including the ‘expan<strong>de</strong>d<br />

cinema’ and synaesthetic and<br />

multi-sensorial experiences in multiple<br />

formats. Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar was also one of<br />

the pioneer technologists in Europe in<br />

audiovisual projects and patents: from<br />

the variable angle lens (now zoom) in<br />

1928, to diaphonic sound patented in<br />

1944, the apanoramic image overflow<br />

and the tactile-vision of the 50s and<br />

60s, to multimedia experiments with<br />

vi<strong>de</strong>o, laser and other techniques in the<br />

70s and 80s.<br />

When he was young he took part in<br />

the Misiones Pedagógicas of the Republic,<br />

where he took thousands of photos<br />

and ma<strong>de</strong> dozens of documentary films,<br />

most of them lost in the Civil War. Five<br />

of these have survived: Estampas 1932,<br />

mounted by Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar to show the<br />

didactic work of the Missions; three,<br />

restored and grouped together as Fiestas<br />

cristianas/Fiestas profanas (1934-35)<br />

and Vibración <strong>de</strong> Granada (1935) which<br />

is a forerunner of his masterpiece Aguaespejo<br />

granadino (1953-55). Another<br />

crucial work, Fuego en Castilla (1958-<br />

60) won an award at the 1961 Cannes<br />

Film Festival for its tactile lighting. Acariño<br />

galaico was begun the same year<br />

but was not completed until 1995, making<br />

up the three parts of the Tríptico<br />

elemental <strong>de</strong> España.<br />

The Republican period of the young<br />

Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar has been analysed in <strong>de</strong>tail<br />

and compared with other great artists<br />

of the time by Jordana Men<strong>de</strong>lson,<br />

Professor of History of Art at New York<br />

University in her book Documenting<br />

Spain: Artists, Exhibition Culture and the<br />

Mo<strong>de</strong>rn Nation, 1929-1939. (2005)<br />

In his last years, in his PictoLumínicaAudioTáctil<br />

laboratory(PLAT) —which<br />

still exists— Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar <strong>de</strong>veloped<br />

many techniques (Óptica Biónica Ciclo<br />

Táctil, Palpicolor, Cromatacto, Bi-Standard,<br />

Intermediate 16-35, etc.) and worked<br />

on various projects including several<br />

unfinished experiments: El color <strong>de</strong><br />

mi Granada, Variaciones sobre una granada,<br />

Festivales <strong>de</strong> España, Festival <strong>de</strong> las<br />

entrañas, etc. as well as photomontage,<br />

series of double sli<strong>de</strong>s, techno-poetic<br />

texts and multimedia experiments.<br />

ENGLISH<br />

Fuego en Castilla,<br />

centre of the Tríptico elemental<br />

<strong>de</strong> España<br />

Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar wanted his Triptych to be<br />

projected in the opposite or<strong>de</strong>r to how<br />

it had been ma<strong>de</strong>. But its ‘elements’ go<br />

beyond those of the Greeks or those of<br />

Raimon Llull. They are more those of<br />

Taoism and subatomic physics: from the<br />

muddy confines of Galicia, to the unending<br />

fire of Castilla and the infinite flight<br />

of the water in Granada, Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar<br />

submerges us in a grandiose symphony<br />

where the world or<strong>de</strong>r is shattered, bombar<strong>de</strong>d<br />

as if in a particle reactor by the<br />

energy and <strong>de</strong>pth of his vision. As if in a<br />

subatomic cosmos, all is rhythm, different<br />

levels, incessant change. The elements<br />

of this universe are not so much<br />

dynamic as chaotic, transitory stages in<br />

the unceasing flow of transfiguration. In<br />

his poems Tientos <strong>de</strong> erótica celeste, the<br />

artist <strong>de</strong>scribes it as:<br />

Eléctrico éxtasis:<br />

movimiento continuo en alta frecuencia<br />

Temblor vertical<br />

que se sumerge en la clarivi<strong>de</strong>ncia<br />

Ardor, temblor <strong>de</strong> viva luz

(Electric ecstasy/high frequency<br />

perpetual motion /Vertical tremor/<br />

submerged in clairvoyance/Passion,<br />

trembling of live light)<br />

The first ‘elemental’ of the Triptych,<br />

Acariño galaico (De barro), was begun in<br />

1961 but was not completed until 1995,<br />

following his scripts. This is its author“s<br />

darkest work, a journey to the harsh<br />

beginnings of the West: the masses of<br />

clay which the sculptor attempts to mo<strong>de</strong>l,<br />

the creatures of the mud (witches,<br />

frogs, eels), the all-seeing eye of God,<br />

the celebrants who blacken everything,<br />

the terrible shots fired in the mired coup<br />

d“etat: War in Heaven and on Earth. Val<br />

<strong>de</strong> Omar himself <strong>de</strong>scribes his intentions:<br />

‘We come from water —ma<strong>de</strong> of<br />

clay- the fire of life— dries us; we pass<br />

through passion —which saps us— of<br />

laughter and of tears; and in the end we<br />

are left —motionless— imprisoned’.<br />

The second ‘elemental’, Fuego en<br />

Castilla (Táctil Visión <strong>de</strong>l páramo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

espanto), is the central and most complex<br />

movement of Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar’s great<br />

symphony: mystic or (as he said himself)<br />

meca-mystic thanks to technology,<br />

transcending the flamenco rhythms of<br />

the percussion of Vicente Escu<strong>de</strong>ro on<br />

the woods in the Museum in Valladolid,<br />

it brings them to life and makes them<br />

dance and catch fire before the very eyes<br />

of the astonished spectators.<br />

An authentic introduction of Val <strong>de</strong><br />

Omar <strong>de</strong>scribes these otherworldly visions<br />

like this: ‘Castilla is presented without<br />

colour or melody, without tones<br />

or words. In the jondo mono-rhythm of a<br />

blind tremor of nails, faced with a world<br />

which is ready and about to submerge<br />

itself in the great spectacle of the invasion<br />

of the Valley of Differences by the<br />

Fire which will integrate us once again<br />

into Unity’.<br />

But the end is hopeful in the author’s<br />

own words: ‘Death is only a word which<br />

is left behind when there is love. He who<br />

loves, burns and he who burns flies at<br />

the speed of light. Because loving is…<br />

being what is loved’. In the context of<br />

this masterpiece Roman Gubern commented<br />

that: ‘The lighting experiments<br />

of Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar inspired similar uses in<br />

the international experimental cinema<br />

of the <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> (e. g. Werner Nekes and<br />

Stan Brakhage) and led their inventor<br />

logically to the Palpicolor (1961-63) and<br />

Cromatacto (1967) projects’.<br />

Finally, Aguaespejo granadino (La<br />

gran siguiriya) is the first ‘elemental’<br />

which Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar completed and last<br />

to be projected. This work, with more<br />

than 500 sounds processed with diaphonic<br />

technology, was more than a<br />

quarter of a century ahead of the mo<strong>de</strong>rn<br />

concept of sound <strong>de</strong>sign. The images<br />

are also amazing: in the 1956 Berlin<br />

Festival, Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar was consi<strong>de</strong>red as<br />

the Schönberg of the camera, the discoverer<br />

of atonal film language. Along<br />

with the greatest homage ever paid to<br />

cante jondo in the cinema, Val <strong>de</strong>l Omar<br />

<strong>de</strong>scribes his work with a humble lyricism:<br />

‘One day I heard Fe<strong>de</strong>rico and<br />

this is what he was asking for: Lord, give<br />

me ears to un<strong>de</strong>rstand the waters. And<br />

now I am the one who is asking you to<br />

lend me your ears to hear them. For as<br />

the path I have taken is not the real one<br />

of direct emotions, you have to go and<br />

look for this small trail of images and<br />

cries which runs quickly, hid<strong>de</strong>n at times<br />

among the grass.’<br />

Text: Gonzalo Sáenz <strong>de</strong> Buruaga<br />

www.val<strong>de</strong>lomar.com<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in this room.<br />

ENGLISH

ROOM 14. BAROQUE AND COUNTER- REFORMATION ART<br />

Reliquary retables of San Diego 1604-1606<br />

Vicenzo and Bartholomew Carducci; Juan <strong>de</strong> Muniátegui (joiner)<br />

Gilt, polychrome wood and oil on canvas<br />

While the Court was in Valladolid, between<br />

1601 and 1606, the Duke of Lerma,<br />

following the royal example, acted<br />

as a great patron of the arts, commissioning<br />

new religious houses and their<br />

embellishment. For the convent of San<br />

Diego he commissioned these two reliquary<br />

altarpieces, now restored to their<br />

original arrangement. Various artists<br />

took part in their <strong>de</strong>sign and execution:<br />

the royal architect Francisco <strong>de</strong> Mora,<br />

Juan <strong>de</strong> Muniátegui who assembled<br />

them and Vicente and Bartolomé Carducho,<br />

the artists responsible for the<br />

paintings.<br />

These reliquaries were ma<strong>de</strong> to imitate<br />

the reliquary aumbries in the Monastery<br />

of El Escorial, and follow a monumental<br />

classicist <strong>de</strong>sign: a pre<strong>de</strong>lla of<br />

painted board, a main panel with two<br />

Corinthian pilasters and a pediment.<br />

They can be closed with two large wing<br />

panels, with paintings of the Annunciation<br />

and the Stigmata of St Francis of<br />

Assisi. These are unusual in that they<br />

are double-si<strong>de</strong>d, with the same scene<br />

repeated on each si<strong>de</strong> of the leaves.<br />

The interior contains reliquaries in<br />

the shape of busts and arms, highlighting<br />

the link between statue and relic. The<br />

image was the catalyst of the power of<br />

the relics, and the veneration of these<br />

was the essential aim. They were then<br />

placed in a scenario which captured the<br />

attention of the believers. (Room 14)<br />

The Baptism of Christ 1624-1628<br />

Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

Consi<strong>de</strong>red by many art historians as<br />

one of the masterpieces of Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z,<br />

this scene occupied the central<br />

panel of the altarpiece for the Chapel of<br />

St John the Baptist in the convent of the<br />

Discalced Carmelites.<br />

Following the biblical story, the artist<br />

reconstructs the Baptism of Christ with<br />

two superimposed scenes: the Purification<br />

of Christ in the waters of the Jordan<br />

and the theophany or visible manifestation<br />

of God in this act. The purification<br />

of baptism takes on more importance<br />

and reflects the doctrinal novelties of<br />

the Counter-Reformation Church: Christ,<br />

who had been represented up to then<br />

in the centre of the composition, standing<br />

and with a loin cloth, is shown here<br />

kneeling humbly in front of St John the<br />

Baptist, his arms crossed on his breast<br />

as a sign of selflessness and covering his<br />

nakedness with a flowing robe.<br />

The two main figures are a marvel<br />

of naturalism in their anatomical repre-<br />

sentation with <strong>de</strong>tailed carvings of veins,<br />

tendons and muscles (more <strong>de</strong>licate in<br />

the figure of Christ, more sinewy in the<br />

figure of the Precursor). The <strong>de</strong>tailed<br />

treatment of the hair and of the ample,<br />

heavy cloth falling in sharp stiff folds,<br />

have the clear marks of this artist’s mature<br />

style. (Room 14)<br />

ENGLISH

The Pietà 1616<br />

Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

This forms part of a paso or processional<br />

group commissioned from the<br />

sculptor by the Cofradía <strong>de</strong> Nuestra<br />

Señora <strong>de</strong> las Angustias, which also inclu<strong>de</strong>d<br />

two other figures —Mary Magdalene<br />

and St John— now kept in the<br />

church of this Cofradía or Brotherhood<br />

and a bare cross. Dated 1616, a sober<br />

polychromy was applied in 1617, in<br />

keeping with the scene narrated.<br />

The style of Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z is<br />

clearly shown in this work: naturalism,<br />

sharp broken folds, expressive faces<br />

and hands, the plastic quality of the<br />

anatomy. The central group of the Pietá<br />

shows the Virgin Mary looking up<br />

to heaven with a gesture of sorrowing<br />

reproach, while keeping a firm hold,<br />

with a most expressive hand, on the<br />

body of Jesus, which seems to be slipping<br />

off her lap. The composition here<br />

adopts the formula set by Correggio<br />

since 1522 and which had become<br />

wi<strong>de</strong>spread throughout Europe in the<br />

engravings of Carracci, showing Jesus<br />

now no longer on his mother’s knees,<br />

but lying on the ground with his head<br />

resting on her lap, in a highly dramatic<br />

baroque diagonal asymmetry. The two<br />

thieves are magnificent anatomical<br />

studies; they can be seen as the consi<strong>de</strong>red<br />

moral contrast of good and evil<br />

embodied in Dimas and Gestas and<br />

which respond to the need for a clear<br />

narrative required in the processional<br />

group. (Room 14)<br />

Saint Theresa of Jesus 1625<br />

Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

The images of the Saint multiplied after<br />

her beatification in 1614, when Gregorio<br />

Fernán<strong>de</strong>z ma<strong>de</strong> the statue for the<br />

convent of the Discalced Carmelites in<br />

Valladolid. This image has been used as<br />

a mo<strong>de</strong>l with slight variations by Fernán<strong>de</strong>z<br />

himself and other artists ever<br />

since: Saint Teresa, the writer with quill<br />

and book, receiving divine inspiration. It<br />

seems likely that the figure in the Museum<br />

was commissioned near the time<br />

of her canonization (1622) but its existence<br />

is only known of with any certainty<br />

in 1625, when the Dominicans of San<br />

Pablo in Valladolid contracted Bartolomé<br />

<strong>de</strong> Cár<strong>de</strong>nas to polychrome some<br />

works by Fernán<strong>de</strong>z and specified that<br />

some <strong>de</strong>tails should be as rich and beautifully<br />

executed as those of the Saint Teresa<br />

in the Carmelite convent.<br />

And so the dark brown Carmelite habit<br />

is enlivened with a white cloak with<br />

a wi<strong>de</strong> bor<strong>de</strong>r imitating precious stones<br />

set in gold. In her left hand the Saint<br />

is holding an open book with splendi-<br />

Please leave this information sheet<br />

in the stand in Room 14.<br />

dly imitated inscriptions, including the<br />

name of her confessor, Pedro <strong>de</strong> Alcántara.<br />

The strange arrangement of the<br />

cloak on the left si<strong>de</strong>, fixed to the habit<br />

to allow greater liberty of movement (in<br />

line with the fashion of the time which<br />

the artist also shows in other works)<br />

helps to emphasize her ecstatic surprise<br />

(leaving go of cloak and book), breaking<br />

the symmetry and giving the work greater<br />

movement. (Room 14)<br />

ENGLISH

ROOMS 15 - 19. THE BAROQUE. THE ART OF PERSUASION<br />

Saint John the Evangelist around 1638<br />

Juan Martínez Montañés<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

At the beginning of the 17 th century,<br />

the representations of the two saints<br />

John the Baptist and John the Evangelist<br />

took on a special prominence in the<br />

convents and monasteries in Seville as<br />

contrasting examples of the active life<br />

of the preacher —the Baptist— and the<br />

contemplative life of prayer — the Evangelist.<br />

The sculptor Martínez Montañés<br />

created some of the most successful<br />

series of both these Saints.<br />

This sculpture offers a vision of the<br />

mature St John the Evangelist, seated<br />

and writing —with his usual eagle, the<br />

symbol of his lofty texts. The moment<br />

of divine inspiration is reflected in his<br />

body paralyzed by emotion and his face<br />

looking yearningly up to heaven.<br />

The elegant, balanced attitu<strong>de</strong> of<br />

the figure with its rich polychromy and<br />

the gold of the estofado (which may be<br />

by Francisco Pacheco), recalls the classicist<br />

survival in the baroque in Andalucia.<br />

The superb technique of Martínez<br />

Montañes, who was called ‘the god of<br />

wood’ by his contemporaries, can be<br />

clearly seen in this late work, carved<br />

when he was around 70 years old, with<br />

its outstanding treatment of the folds<br />

of the robes and the <strong>de</strong>tail of the locks<br />

of the hair and beard. (Room 16)<br />

Saint Peter of Alcántara around 1663<br />

Pedro <strong>de</strong> Mena<br />

Polychrome wood<br />

The sculptor Pedro <strong>de</strong> Mena from Granada,<br />

just like Gregorio Fernán<strong>de</strong>z, was<br />

also an important creator of iconographic<br />

types whose success resulted in<br />

the continued <strong>de</strong>mand by his clients<br />

for repeats of the mo<strong>de</strong>l. A magnificent<br />

example of this is the iconography of the<br />

Spanish Franciscan saint, Pedro <strong>de</strong> Alcántara,<br />

canonized in 1669, who was the<br />

driving force behind the strictest branch<br />

of the Franciscans in Spain, known as<br />

‘<strong>de</strong>scalzos’ or ‘alcantarinos’. His physical<br />

appearance —tall, bald and gaunt— vividly<br />

<strong>de</strong>scribed by St Teresa of Avila as<br />

‘so extremely thin that he seemed to be<br />

ma<strong>de</strong> of roots of trees ‘- was codified in<br />

the engravings of him ma<strong>de</strong> just before<br />

his beatification in 1622.<br />

The images of the saint attributed to<br />

Pedro <strong>de</strong> Mena and his workshop follow<br />

this mo<strong>de</strong>l: the saint is shown standing<br />

as he writes (here the book and quill<br />

have not survived) with his writing suspen<strong>de</strong>d<br />

momentarily as he attends to<br />

the dictates of the Holy Spirit, raising his<br />

eyes to heaven and waiting anxiously for<br />

divine inspiration. His body, gaunt and<br />

worn from penitence and <strong>de</strong>privation, is<br />

clothed in a rough patched habit, sometimes<br />

with the short cloak of the Discalced<br />

Franciscans.<br />

This iconography of the saint as the<br />

‘mystic Doctor’ may have been inspired<br />

by similar representations of Saint Teresa.<br />

(Room 16)<br />

ENGLISH

Head of Saint Paul 1707<br />

Juan Alonso Villabrille y Ron<br />

Polychrome wood, horn and glass<br />

Starting from what had already been<br />

accomplished by the 17 th century artists<br />

and still with a faint echo of other<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>ls of the profane terribilità, such<br />

as the Gorgon’s head (with the frontal<br />

position, the tortured expression<br />

and the halo of hair), Villabrille turns<br />

this theme of the severed head into<br />

a masterpiece, clearly in line with the<br />

Counter-Reformation obsession with<br />

suffering and <strong>de</strong>ath. Dramatically<br />

placed against a rocky background simulating<br />

trickling water —illustrating<br />

the legend of the three streams which<br />