RITA DUFFY - MID-TERM REPORT Denise Ferran assesses the art ...

RITA DUFFY - MID-TERM REPORT Denise Ferran assesses the art ...

RITA DUFFY - MID-TERM REPORT Denise Ferran assesses the art ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Rita Duffy began her second level<br />

education at St Dominic's High<br />

<strong>RITA</strong> <strong>DUFFY</strong> - <strong>MID</strong>-<strong>TERM</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

School on <strong>the</strong> Falls Road, Belfast in<br />

1970; an eleven-year-old who crossed<br />

town to go to school daily, in a city<br />

exploding with 'The Troubles'.<br />

Immediately she demonstrated a natural<br />

drawing ability, evident in <strong>the</strong> top <strong>art</strong><br />

examination grades she achieved which<br />

usually lead to a BA at Belfast College<br />

of Art and Design. Never<strong>the</strong>less, she was disillusioned by stu<br />

dent life and 'almost left to do something else because [she]<br />

fought so hard to get in <strong>the</strong>re'.' College attention, she felt,<br />

turned its back on <strong>the</strong> city, which lay bombed and bleeding out<br />

side, while inside <strong>the</strong> cloistered walls lecturers adumbrated <strong>the</strong><br />

conceptual difference between two squares of yellow.<br />

Subsequently, Belfast, <strong>the</strong> city of her birth, became <strong>the</strong> catalyst<br />

for works she developed during her MA course at <strong>the</strong> University<br />

of Ulster in 1984. The emerging <strong>art</strong>ist <strong>the</strong>n began to take 'on<br />

<strong>the</strong> issues and st<strong>art</strong> making visual <strong>art</strong> that meant something to<br />

[her]'.2 An early exhibition in 1989, entitled Issues, brought<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r a group show of four women <strong>art</strong>ists who were MA stu<br />

dents toge<strong>the</strong>r - Rita Duffy, Marie Barrett, Alice Maher and<br />

<strong>Denise</strong> <strong>Ferran</strong> <strong>assesses</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong> of a Belfast painter<br />

whose work is a response to<br />

her troubled homeland<br />

Louise Walsh.' Rita Duffy's work drew<br />

from her private world, her life as a<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r, wife and <strong>art</strong>ist; <strong>the</strong> juggling of<br />

roles, of images and imagining. Her mar<br />

riage to architect John Kelly meant<br />

moving house only a few doors from her<br />

parents, <strong>the</strong> world of her childhood<br />

widened. This afforded in <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist a<br />

rare sense of historical continuity.<br />

Issues focused on <strong>the</strong> way each of <strong>the</strong><br />

four <strong>art</strong>ists confronted individual problems in 'one's develop<br />

ment and personal situation'.4 In her four self-portraits Rita<br />

Duffy 'sees herself as chameleon, as seductress, housewife and<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r juggling roles in her daily routine with <strong>the</strong> tempo of daily<br />

living, increasing, after <strong>the</strong> birth of <strong>the</strong> developing baby in her<br />

womb.5 The multiplicity of roles she was performing needed<br />

many arms in order to feed her baby herself while continuing<br />

with <strong>the</strong> domestic chores of ironing, cooking and cleaning. The<br />

seductress and lover is hinted at in <strong>the</strong> black lacy bra, black silk<br />

stockings, high-heels or fluffy mules. Her role as lover has been<br />

subsumed in that of wife and mo<strong>the</strong>r. There is a hint of roman<br />

tic evenings past with two champagne glasses, empty on <strong>the</strong><br />

tray. The exhibition was assembled for touring to venues<br />

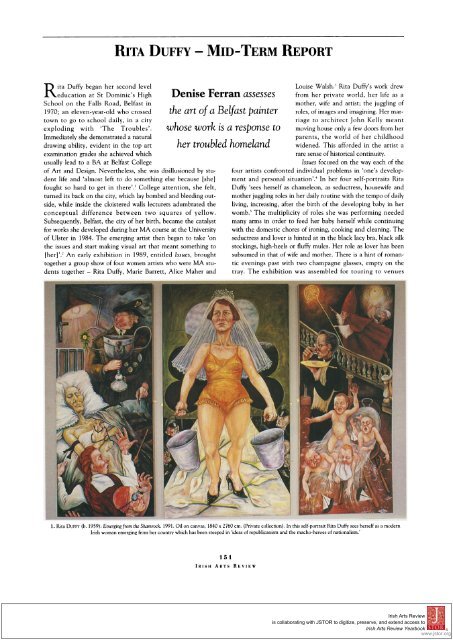

1. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong> (b. 1959): Emerging from <strong>the</strong> Shamrock. 1991. Oil on canvas, 1840 x 2760 cm. (Private collection). In this self-portrait Rita Duffy sees herself as a modern<br />

Irish woman emerging from her country which has been steeped in 'ideas of republicanism and <strong>the</strong> macho-heroes of nationalism.'<br />

151<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW<br />

Irish Arts Review<br />

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<br />

Irish Arts Review Yearbook ®<br />

www.jstor.org

<strong>RITA</strong> <strong>DUFFY</strong> - <strong>MID</strong>-<strong>TERM</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

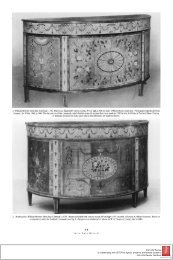

2. Rita DuTFn-': The Legacy of t/ie Borvie. 1989. Oil on gesso board, 920 x 1220 cmi.<br />

(Collectioni of <strong>the</strong> University of Ulster). The Battle of <strong>the</strong> Boyne, 1690, was <strong>the</strong> decisive<br />

baittle of <strong>the</strong> Williamiite war betweeni jamies 11, th-e Cathiolic Kinig of Englanid anid William<br />

of Orange, whio, when victorioLIS, becamie William 111, <strong>the</strong> Protestant Kinig of Eniglanid.<br />

throughout Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland but, because <strong>the</strong> subject matter<br />

was felt by many local authorities to be contentious, <strong>the</strong> exhibi<br />

tion received little exposure.<br />

The next major works Duffy showed were in a solo exhibition<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Arts Council Gallery in Belfast. Ten paintings were<br />

selected for inclusion in an exhibition entitled On <strong>the</strong> Balcony of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Nation which toured for two years in <strong>the</strong> United States.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> exhibition was shown in Alabama, James Nelson <strong>art</strong><br />

critic of <strong>the</strong> Birminghiam News and Director of <strong>the</strong> Alabama<br />

School of Fine Art, wrote on <strong>the</strong> 28 April 1991: 'Rita Duffy<br />

defines <strong>the</strong> character of her subjects through caricature.<br />

Devastating exaggerations give precise meaning to <strong>the</strong> pernicious<br />

nature of generational poverty, she shows us that if something<br />

goes on long enough, it becomes <strong>the</strong> norm. Small worlds, narrow<br />

minds, insular attitudes, bigotry and poverty create a sad and vio<br />

lent state of affairs.'6 In <strong>the</strong>se works she moved out from her<br />

domestic world into <strong>the</strong> destructive world outside her studio win<br />

dow, <strong>the</strong> 'Troubles' which had haunted Belfast since Rita Duffy<br />

had turned twelve years of age. The anger in <strong>the</strong>se works spilled<br />

out into large charcoal drawings like Eleventh Night in The Jubilee<br />

152<br />

IRIS1-1 ARTS REVIEW<br />

3. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Eleventh Night in The Jtbilee. 1989. Charcoal on paper,<br />

920 x 1220 cm. (Private collection). Jubilee, <strong>the</strong> name of <strong>the</strong> maternity unit at<br />

<strong>the</strong> City Hospital, Belfast, is adjacent to Sandy Row, a loyalist area where<br />

bonifires are lit on <strong>the</strong> night before <strong>the</strong> Twelfth of July.<br />

(Fig. 3) Here three women are drawn toge<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong>ir common<br />

confinement, marooned inside <strong>the</strong> hospital maternity ward, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> sectarian violence raging outside. Becoming a mo<strong>the</strong>r focuses<br />

Duffy's attention on <strong>the</strong> violent disrupted society in which her<br />

young son will grow up, a society which she can try to change. If<br />

she fails to do so, she must continuously protect hi, in it. She<br />

looks at <strong>the</strong> three-hundred year history that divides her city in<br />

The Legacy of <strong>the</strong> Boyne (Fig. 2); bodies flow in a river which is an<br />

extension of <strong>the</strong> Orangeman's sash, as he brandishes his cutlass.<br />

Thatched cottages glow as beacons in bloodied landscape. Inbred<br />

hatred is never ending, tolerance is swept away in its tide. The<br />

Marley Funeral is set in Ardoyne, a poor Catholic area in North<br />

Belfast, close to <strong>the</strong> equally poor Protestant Shankill. Larry<br />

Marley's funeral procession was delayed for several days by <strong>the</strong><br />

RUC and <strong>the</strong> British Army, while protracted negotiations ensued<br />

to suppress Republican burial honours. He had been shot dead by<br />

Loyalists at Easter 1987, but Duffy did not complete her work<br />

Lintil two years later. Amidst <strong>the</strong> turmoil described in <strong>the</strong> paint<br />

ing, Rita Duffy was teaching Food Science in a local secondary<br />

school. Her self-portrait, which is included in <strong>the</strong> foreground,

I -.<br />

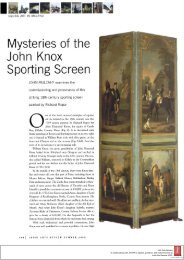

4. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: MOthler IreLhid. 1989. Oil on gesso, 920 x 1220 cii. (Private<br />

collection). Rita Duffy depicts Mo<strong>the</strong>r Irelanid, inot in <strong>the</strong> traditional imilage of <strong>the</strong><br />

pillaged cotuntry seeking freedomii from <strong>the</strong> conqtiering oppressor, bLut as a harassed<br />

miio<strong>the</strong>r conitrolled by <strong>the</strong> power of <strong>the</strong> Catholic chtircih.<br />

shows her with a book in one hand and a saucepan in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

highlighting <strong>the</strong> incongruity of <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist teaching unfamiliar sub<br />

ject matter to uninterested girls, while a life-and-death struggle<br />

unfolded in <strong>the</strong>ir neighbourhood. The black road with its central<br />

white line becomes <strong>the</strong> division between <strong>the</strong> ordered, helmeted<br />

and uniformed security forces on <strong>the</strong> left and <strong>the</strong> disorganised<br />

angry mob on <strong>the</strong> right. A priest blesses <strong>the</strong> body while one of <strong>the</strong><br />

crowd tugs at <strong>the</strong> rosary beads entwined in Marley's hands, which<br />

are stiff in death.<br />

At that time two oil paintings of a similar large scale - Mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Ireland (Fig. 4) and Mo<strong>the</strong>r Ulster (Fig. 5), both painted in 1989,<br />

were shown in A New Tradition - Irishi Art of <strong>the</strong> Eighties at <strong>the</strong><br />

Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin in 1990. Mo<strong>the</strong>r Ireland, dressed<br />

in sombre black with a hint of clerical robes, her eyes raised to<br />

heaven, clutches four struggling young toddlers, each presum<br />

ably representing a province of Ireland. In <strong>the</strong> background <strong>the</strong><br />

spired church and mitred bishop emphasise Duffy's recurrent<br />

criticism of <strong>the</strong> Catholic Church and its control of family life.<br />

The lurid pink of <strong>the</strong> babies' skin contrasts grimly with <strong>the</strong> black<br />

of <strong>the</strong> clerical costume. Humorously, an iron creates a hat above<br />

<strong>RITA</strong> <strong>DUFFY</strong> - <strong>MID</strong>-TERm <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

1 53<br />

IRIS H ARTS REVIEW<br />

5. Rita Dully: Mo<strong>the</strong>r Ulster. 1989. Oil oll gesso, 920 x 1220 cm. (Private<br />

collectiol). In this work Ritai D6ffy depicts <strong>the</strong> grim existenlce of <strong>the</strong> imio<strong>the</strong>r<br />

who raises her children in a loyalist, British environment.<br />

her heavy unsmiling face. Mo<strong>the</strong>r Ulster is equally foreboding<br />

and grim, with <strong>the</strong> statutory two children, a boy and a girl, play<br />

ing at her feet. She brooks no nonsense in her floral patterned<br />

pinny, against a backgound of terrace houses and a lone drum<br />

mer. Her soured expression and steel grey hair offer no relief.<br />

Every inch of her 'says no'.<br />

In Comfortable Woman (Fig. 6) a middle-class woman sits at her<br />

dressing-table. An eerie light is reflected in <strong>the</strong> pinks and blacks<br />

of <strong>the</strong> bedroom and in <strong>the</strong> brass bed a tiny figure is glimpsed.<br />

From childhood to adulthood she has remained cocooned from<br />

<strong>the</strong> violence erupting in <strong>the</strong> darkness beyond her bedroom win<br />

dow. Those caught up in <strong>the</strong> unrelenting tragedy cannot turn<br />

away, nor escape. The influence of Otto Dix's Portrait of <strong>the</strong> writer<br />

Sylvia Von Harden (1926) is evident in this work.<br />

Rita Duffy paints <strong>the</strong>se images informed by <strong>the</strong> community in<br />

which she lives and works. For three years she worked as an offi<br />

cial <strong>art</strong>ist in <strong>the</strong> community and used her former primary school,<br />

St Malachy's in <strong>the</strong> Markets area, as a studio. During <strong>the</strong>se years<br />

she painted large murals with young people, forging a bond in<br />

<strong>the</strong> divided communities, raising esteem and adding joyful

<strong>RITA</strong> <strong>DUFFY</strong> - <strong>MID</strong>-<strong>TERM</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

6. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Comfortable Woman. 1989. Oil on gesso, 120 x 90 cm. (Private collection). The middle-class<br />

woman has been cocooned from <strong>the</strong> violence (seen through her bedroom window on <strong>the</strong> right) from childhood,<br />

as indicated by <strong>the</strong> little figure in <strong>the</strong> bed in <strong>the</strong> background, to adulthood.<br />

imagery to dreary environments. This commitment, although<br />

<strong>art</strong>istically rewarding, took her away from her easel painting.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less she has continued to work on <strong>the</strong>mes of interpre<br />

tation in <strong>the</strong> community and recently completed a project in <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Victoria Hospital for Sick Children. In a more cloistered<br />

environment she was <strong>art</strong>ist-in-residence for three months in<br />

1993 at <strong>the</strong> Ulster Museum.<br />

In 1991 she p<strong>art</strong>icipated in <strong>the</strong> large exhibition In a State held<br />

in Kilmainham Prison's East Wing in Dublin. She exhibited a<br />

large triptych Emerging from <strong>the</strong> Shamrock (Fig. 1). The central<br />

panel is a self-portrait of <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist with bridal veil, gold satin<br />

underwear and black high heels, emerging from a background<br />

shamrock. She walks along <strong>the</strong> catwalk which is strewn with<br />

154<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW<br />

white Easter lilies, carrying two zinc<br />

buckets. Becapped, uniformed officers<br />

view upwards, disapprovingly. Rita Duffy<br />

recalls that this image came from Margo<br />

Harkin's film Mo<strong>the</strong>r Ireland, which was<br />

in p<strong>art</strong> inspired by early footage of a Rose<br />

of Tralee contest. The young contestants<br />

marched through a cardboard shamrock<br />

and Duffy lampooned this as Irish wom<br />

anhood taking a step into <strong>the</strong> twenty<br />

first century. Her triptych expresses<br />

disillusionment 'with ideals of republi<br />

canism and <strong>the</strong> macho-heroes of nation<br />

alism'.7 The panel on <strong>the</strong> right symbolises<br />

government, with memories of hunger<br />

strikers interwoven with authoritative<br />

figures from Irish history. The panel on<br />

<strong>the</strong> left is dominated by a priest and<br />

bishop, while a zinc bath overturns, emp<br />

tying out its four babies, alluding to <strong>the</strong><br />

control of <strong>the</strong> church exercised by <strong>the</strong><br />

church through family planning. There<br />

were four children in <strong>the</strong> Duffy family,<br />

three girls and a boy; <strong>the</strong> colouring and<br />

features of <strong>the</strong> children in <strong>the</strong> painting<br />

resemble <strong>the</strong> Duffy children.<br />

In 1995 Rita Duffy embarked on a<br />

series of paintings entitled Palimpsest,<br />

commissioned for an exhibition which<br />

opened at <strong>the</strong> Foyle Arts Centre in<br />

Derry. One of <strong>the</strong>se works, Journey<br />

(Fig.7), is symbolically set inside a car;<br />

enclosed with a background of religion<br />

and with <strong>the</strong> Virgin Mary as model,<br />

Duffy travels onwards, playing her own<br />

tune. Her red dress glows like a beacon<br />

in <strong>the</strong> monochrome surroundings. This<br />

painting examines her relationship with<br />

her fa<strong>the</strong>r who filled her imagination<br />

with memories of his past, which is also<br />

<strong>the</strong> past history of Belfast. The Palimpsest<br />

series is a mature body of work, enriched by <strong>the</strong> trappings of<br />

Duffy's childhood which she is attempting to place in context<br />

against a background of sinister elements, ga<strong>the</strong>ring outside.<br />

Frieze 1995 (Fig. 8) is a panorama of childhood recollections<br />

gleaned from <strong>the</strong> happy years spent growing up in South Belfast.<br />

It is a rich, colourful world in front of, or behind, her childhood<br />

home in a street of terraced houses. Unlike her contemporary<br />

Belfast <strong>art</strong>ist, John Kindness, Duffy locates herself at <strong>the</strong> emo<br />

tional centre of her childhood memories. The role of detached<br />

observer does not suit Duffy's persona as it has evolved over <strong>the</strong><br />

last decade, intensely engaged, sharply distilled.<br />

Duffy's world is subjective, she is mostly centre stage, grap<br />

pling to resolve <strong>the</strong> multiplicity and complexity of influences

stored from childhood and gleaned from<br />

her extensive <strong>art</strong> education. These<br />

images are woven toge<strong>the</strong>r in a<br />

Pana<strong>the</strong>nic Frieze of life, pattern and<br />

colour, which shows a little girl with her<br />

two sisters encased in <strong>the</strong>ir private<br />

world. The classical struggle of good<br />

over evil, beauty over ugliness persists,<br />

not in a Herculean epic but in <strong>the</strong><br />

unique life of one girl who describes her<br />

childhood in painting and drawing.<br />

There is washing on <strong>the</strong> line, bacon and<br />

eggs frying on <strong>the</strong> pan, a dancer, singer<br />

in <strong>the</strong> band and a menacing cowgirl. She<br />

creates recession, views into rooms, <strong>the</strong><br />

backyard with its bin marked No. 6, <strong>the</strong><br />

row of red brick terrace houses on <strong>the</strong><br />

skyline. These individual roles she<br />

selects and treats individually as Cowboy<br />

Girl (Fig. 9) and Dancing (Fig. 12). She<br />

is in <strong>the</strong> spotlight again, and at her feet<br />

are memorabilia from past years. The<br />

name 'Cowboy Girl' implies ambiguity of<br />

sexual roles, <strong>the</strong> bewilderment of<br />

puberty when toys are cast aside. The<br />

background she treats like wallpaper<br />

sprigged with shamrock sprays. The soft<br />

tonalities of this work are in marked<br />

contrast to <strong>the</strong> lurid reds of Dancing.<br />

Two Women combines <strong>the</strong> tonality of<br />

Cowboy Girl, with a dash of red in <strong>the</strong><br />

skirt of <strong>the</strong> girl on <strong>the</strong> left. These are<br />

perturbing images of two women, one a<br />

self-portrait of <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist standing<br />

cradling her baby while her companion,<br />

in this deserted olain. sits on a dustbin<br />

in jeans holding a cupid on a fork. Her<br />

shield is a dustbin lid, a reference to <strong>the</strong> women in <strong>the</strong> national<br />

ist areas of Belfast and Derry, who, like a classical Greek chorus,<br />

banged <strong>the</strong>ir dustbin lids in unison to warn of <strong>the</strong> approaching<br />

British Army. This modern day Britannia has only <strong>the</strong> domestic<br />

implements of bin and fork to defend her territory. Around her<br />

feet seven little communicants walk in prayer - a reference, per<br />

haps, to <strong>the</strong> innocence and purity of childhood. Devotion is<br />

painted in <strong>the</strong> rich red ochres and siennas of an Egyptian wall<br />

painting. One sister walks along with her feet solidly on <strong>the</strong><br />

ground while <strong>the</strong> younger girl, with hands clasped in prayer, lev<br />

itates beside her. A girl walks with an angel to her left and<br />

within her coat is a small image of a kneeling family of six. A<br />

stoic air hovers over <strong>the</strong> two women. Suffering is seen in <strong>the</strong><br />

face of <strong>the</strong> woman on <strong>the</strong> left as she gazes into <strong>the</strong> distance. Is it<br />

<strong>the</strong> welfare of her child that she fears for and feels she must<br />

defend? Bearing children often dissipates women's creativity and<br />

accommodating mo<strong>the</strong>rhood with creative work can be difficult.<br />

<strong>RITA</strong> <strong>DUFFY</strong> - <strong>MID</strong>-<strong>TERM</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

7. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Jounley. 1995. Oil on wax paper, 116 x 122 cm. (Private collection). In this work Rita Duffy<br />

recalls her childhood memories when she travelled in <strong>the</strong> car with her fa<strong>the</strong>r and he pointed out <strong>the</strong> Belfast of<br />

his boyhood.<br />

155<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW<br />

There is a combination of freedom of paint handling and<br />

images of <strong>the</strong> countryside in <strong>the</strong> Aughamore Series (Fig. 11).<br />

Duffy captures visits out of <strong>the</strong> city to her grandmo<strong>the</strong>r's farm,<br />

chasing <strong>the</strong> white chicken in <strong>the</strong> farmyard <strong>the</strong>n recording it<br />

hung in preparation for <strong>the</strong> dinner table. References to some of<br />

Marc Chagall's work are perceived in <strong>the</strong>se painted experiences.<br />

Many inhabitants of our Irish cities have relatives who live on<br />

farms and summers were times to visit. Long days were spent<br />

bringing turf from <strong>the</strong> bog, helping harvest <strong>the</strong> hay or carrying<br />

water from <strong>the</strong> well and those lyrically-painted landscapes<br />

become backdrops for her narratives.<br />

Duffy combines in her work references to <strong>the</strong> universal strug<br />

gle of women seeking emancipation, although she concentrates<br />

on issues which relate to her own experiences of growing up as a<br />

Catholic girl in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland. She examines in paint and<br />

comes to terms with her situation 'as a woman, a mo<strong>the</strong>r and an<br />

<strong>art</strong>ist within Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland'.' She explores imagery from '<strong>the</strong>

156<br />

I R ISH A R TS R EV\IE W

1ii<br />

- ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \<br />

9. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Cowboy Girl. 1996. 0i1 on gesso canvas, 122 x 122 cm. (Collection of <strong>the</strong> Arts Council of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland). In this work Rita Duffy is examining <strong>the</strong> role<br />

models of her childhood with elements of sexual ambiguities which emerging adolescents must resolve.<br />

8. (Opposite). Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Friez.e. 1995. Oil on wax paper, cotton thread and Japanese paper, 116 x 600 cm. (Private collection). 'This work in p<strong>art</strong>icular describes an<br />

internal space, inside my own head where <strong>the</strong> dreams and half memories that constitute my childhood are explored.'<br />

157<br />

IR I SH A RT S R E vIE W

10. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Emerging 1, 2, 3, 1996. Oil on gesso board, 11. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Augharnore Series. 1996. Oil and wax paper on board, 30 x 30 cm. (Private collection).<br />

30 x 90 cm. (Private collection). 'It's like <strong>the</strong> darkness Visits to her grandmo<strong>the</strong>r's farm in Aughamore allowed Rita Duffy to escape Belfast city streets and<br />

between your jacket and your he<strong>art</strong>, warm and secretive<br />

and memory-filled.'<br />

enjoy <strong>the</strong> sounds and sights of an Irish farmyard of <strong>the</strong> 1960s.<br />

1 58<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW

12. (Opposite). Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Dancing. 1995. Oil on wax paper, 1 16 x 122 cm. (Private collection) . Learning to dance reels, jigs and hornpipes, wearing a full-skirted<br />

costume and lace collar, was p<strong>art</strong> of an Irish childhood but <strong>the</strong> statues strewn at her dancing feet replace <strong>the</strong> customary medals sought and won.<br />

1 59<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW

RiTA <strong>DUFFY</strong> -<strong>MID</strong>-<strong>TERM</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

13. Rita <strong>DUFFY</strong>: Caress. 1996. Charcoal on paper, 122 x 150 cm. (Private collection). 'My drawings seek out <strong>the</strong> cracks in history, throwing light across <strong>the</strong> shadowed<br />

spaces within race-memory itself, illuminating my own fears, yet suspending <strong>the</strong>m, transfinite.'<br />

dreams and half memories9 from her childhood and forms <strong>the</strong>m<br />

into a rich tapestry. Her earlier objective work on <strong>the</strong> plight of<br />

working-class women in Belfast, evident, for example, in her<br />

painting Women of Gallagher's Factory (1986), has been replaced<br />

by images based on her experiences. The maturing of her work<br />

chronicles her own struggle for personal identity, living in a<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland which is divided by sectarian hatred and <strong>the</strong><br />

polarised identity of being British or Irish.<br />

She is also maturing as a woman in Emerging 1 to 3, 1995 (Fig.<br />

10). She springs liberated out of a fur-trimmed jacket but<br />

160<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW<br />

modestly covers her nakedness with both arms in <strong>the</strong> manner of<br />

a Botticelli Venus. In Emerging 3 she sinks into <strong>the</strong> fur collar,<br />

her raised arms and enclosed head forming a seductive phallic<br />

shape. The allusion to quattrocento frescoes is maintained in<br />

<strong>the</strong> scumbling and rubbing of paint into <strong>the</strong> gesso, giving it an<br />

aged rendering. Duffy's interest in fourteenth century Italian<br />

painting was reinforced last summer on a visit to <strong>the</strong> Louvre,<br />

when she encountered a panel depicting <strong>the</strong> patron saint of pris<br />

oners. She had earlier come to know <strong>the</strong> work of Artemesia<br />

Gentileschi, an Italian Baroque woman painter, which gave her<br />

A4'

hope that women could achieve success and serious recognition<br />

as <strong>art</strong>ists.<br />

In an exhibition organised by <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Centre for<br />

Contemporary Art in Sunderland, Duffy was represented by a<br />

new work Holy Ground (1994). This work, in oil on wax paper,<br />

represented a change of medium, giving a different surface tex<br />

ture. Again autobiographical, she kneels with her Stranmillis<br />

terrace home in <strong>the</strong> background. Removed from her surround<br />

ings, her left hand raised in a blessing, she appears to plant a<br />

seed in stoney ground. The ghost of a rat springs up, leaving its<br />

droppings, while <strong>the</strong> dark shapes of corner boys look on.<br />

In her recent work she is still examining questions of national<br />

ity; she finds comfort 'in her own shoes','0 in whatever fits her<br />

and allows her feel comfortable. Interestingly she names <strong>the</strong><br />

large triptych done in charcoal on paper, Awakening Triptych (1)<br />

1996. It deals with Rita Duffy's relationship with her mo<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

with <strong>the</strong> intense experiences of puberty. Duffy is central to each<br />

panel, dressed in her St Dominic's school uniform, with her<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r beside her caring for her in all three panels. Diminutive<br />

statues of St Dominic, armed with a lily, <strong>the</strong> Church or a bible,<br />

remonstrate with her independent attitudes.<br />

The <strong>art</strong>ist looks outward and examines her responses to <strong>the</strong><br />

July 1996 Drumcree stand-off in Drumcree Lily (1996). Here, an<br />

image of an orange lily unfolds, its waxy petals presided over by a<br />

diminutive Orangeman, with drawn sword. The ambivalence of<br />

<strong>the</strong> image derives from Duffy's desire to re-appropriate <strong>the</strong> nat<br />

ural beauty of <strong>the</strong> lily, to somehow free it from political or sec<br />

tarian connotations. Caress (Fig. 13), an image of Duffy cradling<br />

and kissing a crocodile, plays with <strong>the</strong> idea of 'dissembling'.<br />

There is a strong suggestion that judicious courting of an adver<br />

sary pays dividends - an oblique political comment.<br />

In Pulsing Rose she examines <strong>the</strong> Plantation of Ulster, <strong>the</strong><br />

tight-budded rose flourishing from roots embedded in <strong>the</strong><br />

buried crown, close by two tied sacks, <strong>the</strong>ir contents undis<br />

closed. She continues this <strong>the</strong>me of colonisation and depicts<br />

<strong>the</strong> presence of occupation and fortification in Speirbhean. She<br />

rises as a dancer, but her outspread skirt is pegged to <strong>the</strong><br />

ground with army and police sentry boxes. Their ominous look<br />

out slits bring a hidden presence into her work, a <strong>the</strong>me devel<br />

oped in The Dark, a powerful black and white image in which<br />

<strong>the</strong> space inside <strong>the</strong> poet's head is transposed into <strong>the</strong> warm,<br />

velvety darkness of <strong>the</strong> canvas.<br />

1. John Farrell, interview with Rita Duffy,<br />

Artists' Stories, Artists' Newsletter, A.N.<br />

Publications, Sunderland, 1996<br />

2. ibid.<br />

3. <strong>Denise</strong> <strong>Ferran</strong>, Issues, exhibition catalogue,<br />

Arts Council of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland, Belfast,<br />

1989<br />

4. Artists' Newsletter (as note 1).<br />

5. <strong>Ferran</strong> (as note 3).<br />

6. James Nelson, Birmingham News,<br />

28 April 1991.<br />

7. In A State, exhibition catalogue, p.31, Project<br />

Arts Centre Ltd., Dublin, 1991.<br />

RiTA <strong>DUFFY</strong> - <strong>MID</strong>-<strong>TERM</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong><br />

8. Rita Duffy, interview, <strong>art</strong> beyond conflict,<br />

exhibition catalogue, Crescent Arts Centre,<br />

Belfast 1995.<br />

9. ibid.<br />

10. Interview with Rita Duffy and <strong>the</strong> author,<br />

Belfast, January 1997<br />

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY.<br />

A New Tradition, Irish Art of The Eighties, exhibi<br />

tion catalogue, The Douglas Hyde Gallery,<br />

Dublin, 1990.<br />

In A State, exhibition catalogue, Project Arts<br />

Centre Ltd., Dublin, 1991.<br />

1 61<br />

IRISH ARTS REVIEW<br />

Irish myth informs <strong>the</strong> source of her work Woodkem and she<br />

becomes one of <strong>the</strong>se war goddesses in disguise. She springs onto<br />

<strong>the</strong> back of a pig, elusive, barefooted and nimble, living in <strong>the</strong><br />

woods, able to dive back into hiding when danger comes. Being<br />

an <strong>art</strong>ist in a divided society demands resourcefulness in main<br />

taining honesty of expression as in Danse Furieuse . She becomes<br />

<strong>the</strong> bullfighter attracting <strong>the</strong> attack of <strong>the</strong> bull. In Armadillo she<br />

resorts to sexual persuasion by provocatively stroking <strong>the</strong> hard<br />

back of <strong>the</strong> animal in an attempt to win. She is examining her<br />

attitudes to male supremacy and chauvinism in <strong>the</strong> uneasy man<br />

ner of Paula Rego.<br />

In her more recent work she experiments with materials, with<br />

gesso and beeswax-covered MDF boards. Her imagery remains<br />

rooted in her environment but she is able to take a more objec<br />

tive view, to look beyond <strong>the</strong> screaming mobs to <strong>the</strong> underlying<br />

power. She examines <strong>the</strong> walls of division, euphemistically<br />

called <strong>the</strong> Peace Line. Each year <strong>the</strong>se dividing lines are<br />

increased and streng<strong>the</strong>ned and have now become architectural<br />

features with town planning considerations and embellishments.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> fifteen panels of The Peace Line, Duffy perceives <strong>the</strong>se<br />

walls as archaeological drawings, <strong>the</strong> natural run of streets inter<br />

rupted, and in <strong>the</strong> names of <strong>the</strong> streets, such as Percy or<br />

Bombay, past and present history merging.<br />

Some of her recent works retain family elements; she contin<br />

ues to explore her relationship with her mo<strong>the</strong>r, now a grand<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r as well, in <strong>the</strong> little Aran jacket she knitted for her<br />

grandson. Duffy <strong>the</strong> daughter pays homage to <strong>the</strong> craft of her<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>ir talents a common heritage. There is a feeling that<br />

she has moved on, that her childhood memories are letting go.<br />

She sees in her mo<strong>the</strong>r's china tea-cup <strong>the</strong> necessity of keeping<br />

up appearances, yet she paints little pink pigs on <strong>the</strong> table and in<br />

<strong>the</strong> teacup. This humorous illusion to <strong>the</strong> stigma of 'having pigs<br />

in <strong>the</strong> kitchen' contrasts with <strong>the</strong> lacy bras hanging as Dada<br />

objects on <strong>the</strong> wall. Her Shoe-piece, exquisitely drawn images of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist's shoes worn over a lifetime, reinforce <strong>the</strong> sense of<br />

journeying, <strong>the</strong> often easy comfort, <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist now feels with her<br />

work. There is a continuing self assuredness in her <strong>art</strong>. Images<br />

are bolder and simpler. She knows now what she intends to say<br />

and has developed <strong>the</strong> means to express it.<br />

DENISE FERRAN is Education Officer at <strong>the</strong> Ulster Museum, and a practising<br />

<strong>art</strong>ist. She is also author of W J Leech (Merrill Robertson 1996), reviewed in this<br />

issue.<br />

Hilary Robinson, Palimpsest, exhibition catalogue,<br />

The Orchard Gallery, Derry, 1995.<br />

Poetic Land - Political Territory, Contemporary Art<br />

from Ireland, exhibition catalogue, Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Centre for Contemporary Art, Sunderland,<br />

1995.<br />

Art beyond Conflict, exhibition catalogue,<br />

Crescent Arts Centre, 1996.<br />

Crossing boundaries: Belfast, contemporary <strong>art</strong> from<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland, exhibition catalogue, San<br />

Francisco State University, 1996.<br />

Artists' Stories, Artists' Newsletter, A.N. Publication<br />

Sunderland, 1996.