ArchiAfrika-April-Magazine-English-final-v2

ArchiAfrika-April-Magazine-English-final-v2

ArchiAfrika-April-Magazine-English-final-v2

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

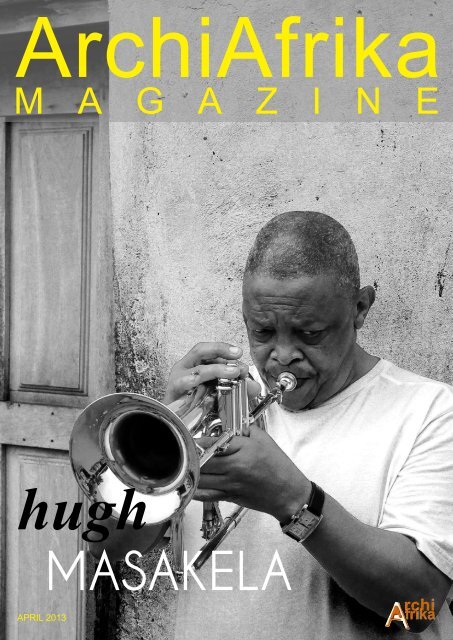

<strong>ArchiAfrika</strong><br />

M A G A Z I N E<br />

hugh<br />

MASAKELA<br />

APRIL 2013

table of CONTENTS<br />

4<br />

6<br />

10<br />

18<br />

28<br />

32<br />

38<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

By Tuuli Saarela, Editor of <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

CHAIRMAN’S CORNER<br />

- All Roads Lead to Lagos via Mumbai and Accra<br />

By Joe Osae-Addo, Chairman of <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> Foundation<br />

AFRICA FLOATS TO MILAN<br />

By Nat Nuno-Amarteifio<br />

INTERVIEW WITH HUGH<br />

MASAKELA<br />

Interview with Hugh Masakela<br />

THE ROAD TO HERITAGE<br />

COMpETITION<br />

By Hugh Masakela<br />

GREEN & YELLOW DIVIDES<br />

ADDIS ABABA<br />

By RIBA Norman Foster Travelling Scholar, Thomas Aquilina<br />

IN SEARCH OF THE ORIGIN<br />

By Jurriaan van Stigt<br />

54<br />

62<br />

74<br />

84<br />

90<br />

96<br />

CAIRO URBANISM<br />

- trash becomes cash<br />

By Zeina Elcheikh<br />

THE REAL ECONOMY<br />

- informal housing, work and the future<br />

a look at Accra and Lagos<br />

By Gilbert Nii-Okai Addy<br />

BUILDINGS TELL A STORY<br />

- 20th century architecture in Kenya<br />

By Janfrans van der Eerden<br />

MSc Arch Architect MAAK<br />

pRESERVING ACCRA’S<br />

ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE<br />

- the need for restoration and preservation<br />

Excerpts from a discussion between Nat Armarteifio, Osei<br />

Agyeman, Senam Okudzeto and Joe Osae-Addo from AiD 13.1<br />

INTERVIEW WITH NIKOS<br />

SALINGAROS<br />

By Zaheer Allam & J. Soopramanien<br />

AFRICAN pERSpECTIVES<br />

LAGOS ‘13<br />

- conference announcement & call for papers

EDITORIAL<br />

Tuuli Saarela<br />

Editor of <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Africa is in an economic boom period, but what<br />

are the true effects on the urban environment?<br />

Is African heritage threatened as we construct<br />

gleaming new skyscrapers? Can we re-establish<br />

the concept of sustainability as a part of our<br />

heritage and identity, rather than an idea that<br />

is a purely Western concept? In this month’s<br />

issue we travel the length and breadth of the<br />

continent to answer some of these questions:<br />

from North Africa (Cairo) to South Africa<br />

( Johannesburg) to the East African hubs of<br />

(Nairobi and Addis Ababa) as well as West<br />

Africa (Dogon, Accra and Lagos).<br />

The contributors in this issue of the<br />

<strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> all speak to common<br />

themes of heritage, identity, sustainability and<br />

urban renewal. These will be explored further<br />

in the 2013 issues of our magazine, to prepare<br />

us for a fantastic debate and exchange of ideas<br />

at the sixth African Perspective Conference<br />

taking place at the Golden Tulip Festac Hotel<br />

in Lagos Nigeria from December 5-8, 2013.<br />

Check out the conference announcement and<br />

call for papers. All Roads Lead to Lagos!<br />

In this issue, we will explore our heritage<br />

through the perspective of one of our great<br />

musical heroes, Hugh Masakela. Hugh has<br />

long been an activist fighting for the promotion<br />

of African heritage who reminds us that our<br />

heritage is something we must preserve,<br />

protect and promote- something that must be<br />

recorded and captured before it is lost under<br />

the deceptive pretense of progress.<br />

Hugh Masakela and <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> are pleased<br />

to announce the first Road to Heritage<br />

Competition for African designers, students,<br />

amateurs and professionals to present<br />

creative proposals to create and promote<br />

spaces of heritage. The competition brief<br />

will be announced in July and entries will be<br />

considered by a world-class panel of judges.<br />

We will <strong>final</strong>ly announce the winner in<br />

December at the AP Conference in Lagos.<br />

In this issue we also visit Kenya to discover<br />

how our heritage and our histories are<br />

under threat. In Nairobi, rapid development<br />

threatens the city’s visual history and Janfrans<br />

van der Eerden reminds us that old buildings<br />

have a story to tell, eliciting thoughts on<br />

how we can organize to preserve buildings of<br />

historical and cultural significance.<br />

Must our histories and heritage be necessarily<br />

lost under the tides of economic development?<br />

Can we learn anything from Gilbert Nii-<br />

Okai Addy who draws parallels between<br />

contemporary Accra, Lagos and 19th century<br />

London- cities which all practice slum<br />

clearing, and cities which ultimately fail to<br />

bring about changes in social policy towards<br />

poor people. Interesting thoughts.<br />

From Addis Ababa, we hear from RIBA<br />

Norman Foster Travelling Scholar Thomas<br />

Acquilina who discovers the causes and effects<br />

of a new government directive to use green<br />

and yellow iron sheets in demarcation of<br />

building sites. He goes beyond beautification<br />

to discover the informal settlements that were<br />

pushed out and also how the informal economy<br />

springs up around them. His writings from six<br />

African cities focus on the recycling practices<br />

of Africans.<br />

Some of our peers have begun to question the<br />

value of sustainability beyond a very alluring<br />

moral facade. Is sustainability too expensive<br />

for Africa? What about the uncomfortable<br />

stigma of sustainability as something that<br />

is actually opposed to progress? While<br />

sustainable approaches can help to bring basic<br />

services to areas that need it most, long-term<br />

viability may depend on the capacity of the<br />

solution to generate income. In Cairo, we<br />

learn from Zeina Elcheikh about how Trash<br />

becomes Cash in the informal settlement of<br />

Ezbet Al-Nasr.<br />

Our contributor Zaheer Allam brings us<br />

an exclusive interview with Professor Nikos<br />

Salingaros, the father of the immensely popular<br />

theory of urban design and fractals, which<br />

seems to have struck a cord with an African<br />

audience. In the interview, we hear Nikos<br />

thoughts on emergent economies, renewable<br />

energy and sustainable construction.<br />

Finally, we are reminded that collaboration<br />

can bring about genuine development of<br />

craft. It is well known that Europeans have<br />

long visited Africa for inspiration, but it<br />

is clear that they also systematically study,<br />

capture and re-interpret our traditional<br />

designs into European architectural styles.<br />

The experience of Foundation Dogon<br />

Education and its Chairman Jurrian van Stigt<br />

shows us that true collaboration is never onesided<br />

but an exchange. An enduring love for<br />

the Pays Dogon and a respect for traditional<br />

architecture, have enabled Dutch and Malian<br />

partners to build schools in Dogon and even<br />

imported Malian design into the architectural<br />

heritage of Amsterdam.<br />

Can contemporary designers establish a true<br />

balance between modern design and African<br />

heritage? What does this look like? Can we<br />

redefine sustainability “In Our Own Words”<br />

and reconnect to our sustainable indigenous<br />

pedigree? We hope that you will continue the<br />

discussions as one of our next contributors for<br />

the July 2013 issue. Do get in touch with the<br />

editorial team if you want to contribute to the<br />

discourse!<br />

Regards,<br />

Tuuli Saarela<br />

4 5

CHAIRMAN’S<br />

corner<br />

ALL ROADS<br />

LEAD TO<br />

LAGOS VIA<br />

MUMBAI AND<br />

ACCRA<br />

Joe Osae Addo<br />

Chairman, <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong><br />

I woke up on the 30th floor of the Renaissance<br />

Hotel in Mumbai to a spectacular view of<br />

the lake and the high rises beyond, a far cry<br />

from the intensely chaotic, but seemingly<br />

synchronized traffic of the previous night’s<br />

arrival in the city from Mumbai airport. The<br />

experience of arriving in Mumbai is strangely<br />

familiar to that of arrival in Lagos and to a<br />

lesser extent, Accra. The familiarity of these<br />

experiences is a clear vestige of colonial British<br />

rule.<br />

Deep thoughts abound as I<br />

reflect on what Ghana, and<br />

the other colonies, could have<br />

become and suddenly I find<br />

myself reminiscing about<br />

the Ghana of my childhood<br />

in the early 1970’s. Ghana in<br />

those days appeared idyllic<br />

with exposure to a modern<br />

way of life firmly rooted in<br />

the passionate love for our<br />

traditions, passed on from<br />

our grand parents.<br />

The previous generation of non-Accra folk,<br />

were born and raised in our hometowns and<br />

villages rather than the cities, and therefore<br />

the first generation of us city children would<br />

still visit the village frequently, and truly<br />

looked forward to our monthly trips out to<br />

experience the change of pace. To me as a<br />

precocious child, modernity embodied being<br />

able to straddle modernity and traditionalism<br />

with ease and without conflict.<br />

Nothing symbolized modernity and Accra<br />

living more than the Ambassador Hotel<br />

(now Movenpick Ambassador Hotel—to<br />

which it bears no resemblance at all), with<br />

its extraordinary swimming pool and grand<br />

international style architecture. As a nine year<br />

old, what mattered most were the delicious<br />

scones and Cornish pies! It was these great<br />

pastries, be it the local or western inspired<br />

ones, which made my Accra tick. My thick<br />

waistline emerged all those years ago, and I<br />

blame it entirely on the Ambassador Hotel!<br />

Early 1970’s Accra was a child’s dream.<br />

Afternoon Boys Scouts meetings at the Ridge<br />

Church School, where I attended primary<br />

school and where my dear mother also<br />

happened to be headmistress, to the Children’s<br />

Theater at the Arts Center, to the music lessons<br />

at the National Symphony where my piano<br />

teacher Mr. Vanderpuye worked: this was my<br />

way of life. We would sometimes ride our<br />

‘banana seat bikes’ around the Ridge School<br />

with dear friends, Amand Ayensu, Joseph and<br />

Michael Kinsley Nyinah, Robert Millls, Adjei<br />

Adjetey, with Afua Sutherland Park and<br />

George Padmore Library as our stomping<br />

grounds. Even then I knew that open space<br />

and good architecture mattered- as embodied<br />

by the spaces described and the Ambassador<br />

Hotel. Life was not so bad at all.<br />

Swimming at the Ambassador was the special<br />

treat any child would crave for. The pool as I<br />

remember it had bright blue tiles, which gave<br />

the water the look of the ocean and made it<br />

appear so large that it commanded my respect.<br />

We jumped from the diving boards with gusto<br />

but were mindful not to be a nuisance to the<br />

regular swimmers. One such ‘hip’ gentleman<br />

that seemed to live in the pool (hahahah) was<br />

‘the famous South African’ Hugh Masekela.<br />

Yes, that was how the pool attendant described<br />

him to us at the time. Hugh was a gentle kind<br />

man, and often obliged our Cornish pasty<br />

habits. We knew that this man was in exile in<br />

Ghana and was a very famous musician. We<br />

revered him, even at that age.<br />

These are very sketchy<br />

memories, but I remember<br />

his easy and commanding<br />

smile and certainly his<br />

generosity and that he lived<br />

in the scion of modernism,<br />

the Ambassador Hotel.<br />

I wonder what he thinks of the new Movenpick<br />

Ambassador, whose amenities I still enjoy<br />

with my family today. My sons Kwaku and<br />

Juhani often run around the hotel, as if they<br />

owned it, much as we did over 40 years ago.<br />

Certain things never change! It’s a shame that<br />

they will never experience the connection to<br />

heritage that such buildings conjured for us<br />

residents of post-colonial Accra.<br />

6 7

As <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> and AiD embark on<br />

engaging in the discourse of preservation and<br />

conservation, these old memories come to<br />

mind, and remind us all of the need to engage<br />

and preserve something of the old Ghana and<br />

Africa that we used to know. AiD has selected<br />

the Children’s Library, a design of Max Fry<br />

and Jane Drew, as a case study of how buildings<br />

can be improved through restoration rather<br />

than decimated by directionless renovation.<br />

Now back to Hugh Masakela, who is our<br />

featured personality for this edition of our<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong>. To me he embodies the aspirations<br />

of a new Africa- proud of its heritage, while<br />

embracing modernity: a redefinition of what<br />

Africa stands for in this global world. He is<br />

the embodiment of the true ‘adventurer in the<br />

diaspora.’ Hugh and his extraordinary wife<br />

Elinam and their children are dear friends of<br />

ours and we are honored that they agreed to<br />

be part of this issue.<br />

With our upcoming theme for 2013 being ‘All<br />

Roads Lead to Lagos’ one cannot ignore the<br />

symbolism of Hugh Masakela being featured<br />

in this issue, as he was very good friends with<br />

another great African activist, Fela Kuti from<br />

Nigeria. Their music is the voice of Africa<br />

and a constant reminder to all us of why our<br />

culture matters.<br />

Hugh Masakela is the kind of advocate for<br />

the cultural and creative renaissance of Africa<br />

that <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> wants to be associated<br />

with, and to learn from.Hugh, thank you<br />

for being ‘a shining light’ and a great role<br />

model for creative people engaging in Africa’s<br />

development agenda. AYEKOO!<br />

Regards,<br />

Joe Osae Addo<br />

Chairman, <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> Foundation<br />

Above: Sketch by Joe Osae-Addo<br />

8 9

AFRICA<br />

floats to<br />

MILAN<br />

By Nat Nuno-Amerteifio<br />

10 11

Above: Kunlé Adeyemi and Nat Nuno-Amertefio in conversation at The Milan Design Week, 2013.<br />

Previous Page: Inset: Makoko Floating School.<br />

Image Courtesy of NLÉ, Shaping the Architecture of Developing Cities<br />

The Milan Design Week hosted designers,<br />

inventors and thinkers from around the world<br />

and enabled them to explore their work and<br />

ideas to their contemporaries. It took place<br />

in <strong>April</strong> when the city draws in breadth after<br />

the winter and watches the trees break into<br />

the first hopeful buds of spring. Events and<br />

exhibitions were displayed in venues across<br />

the metropolis. This gave participants the<br />

opportunity to explore Milan’s incomparable<br />

architectural heritage as well as enjoy its<br />

remarkable transportation infrastructure. This<br />

includes gaily painted trams that look vaguely<br />

familiar until you notice their similarity to<br />

the trams of San Francisco. Indeed the trams<br />

of Milan furnished the prototype for those<br />

in San Francisco. Another engaging urban<br />

feature of the city is the presence of hundreds<br />

of motorcycles and bicycles parked at different<br />

spots and available to residents for a nominal<br />

fee.<br />

The Afrofuture exposition convened<br />

exports from the continent to consider the<br />

impact on African cities of some of the key<br />

questions from various disciplines including<br />

architecture, politics and technology. Using<br />

images from different cities we illustrated<br />

how these questions and issues are shaped in<br />

our discourse and the solutions that emerge.<br />

Presentations were from Lagos, Accra,<br />

Luanda, Nairobi and Dakar.<br />

One topic that provoked animated discussion<br />

was new designs coming from the continent.<br />

This followed the presentation by Kunlé<br />

Adeyemi, a young Nigerian architect<br />

practicing in Amsterdam and Lagos. He<br />

gave an illustrated talk on a school project<br />

he created for an aquatic village called<br />

Makoko in Lagos. Adeyemi belongs to a<br />

new and stimulating generation of African<br />

architects whose works are shaping the<br />

unfolding narrative of contemporary African<br />

architecture. Other practitioners are Joe Osae-<br />

Addo of Ghana and Francis Kéré of Burkina<br />

Faso. These artists, who have arrived at the<br />

apex of their profession, come equipped with<br />

profound understanding of post-modernist<br />

design concepts. They were also educated<br />

in an era when environmental sustainability<br />

was a serious issue. The combination of these<br />

factors and others such as unfair economic<br />

arrangement of international trade has<br />

given them the confidence to examine the<br />

fundaments of design theories in our time. They<br />

have drawn valuable lessons from traditional<br />

African architecture including the social<br />

organization of construction. The application<br />

of these insights gives their projects a fresh<br />

neo-Bantu stamp that is remarkably free of<br />

atavistic posturing. Adeyemi’s presentation<br />

was a welcome introduction of promising new<br />

design from the continent.<br />

Below: Platform prototype. Image Courtesy of NLÉ, Shaping the Architecture of Developing Cities<br />

12 13

These artists, who have<br />

arrived at the apex of their<br />

profession, come equipped<br />

with profound understanding<br />

of post-modernist design<br />

concepts. They were also<br />

educated in an era when<br />

environmental sustainability<br />

was a serious issue. The<br />

combination of these factors<br />

and others such as unfair<br />

economic arrangement of<br />

international trade has<br />

given them the confidence to<br />

examine the fundaments of<br />

design theories in our time.<br />

They have drawn valuable<br />

lessons from traditional<br />

African architecture including<br />

the social organization of<br />

construction. The application<br />

of these insights gives their<br />

projects a fresh neo-Bantu<br />

stamp that is remarkably free<br />

of atavistic posturing.<br />

Inset: Makoko Floating School<br />

Image Courtesy of NLÉ, Shaping the Architecture of<br />

Developing Cities<br />

14 15

Another submission that was full of assurance<br />

was by Cyrus Kabiru, a designer from<br />

Nairobi. He is a brilliant artist who currently<br />

specializes in creating “concept” eyeglasses.<br />

His pieces are fabricated from discarded<br />

machine parts. They are cheeky for their<br />

originality and breathtaking for the audacity<br />

of his imagination. He is master at combining<br />

familiar items in unfamiliar ways. Imagine<br />

a pair of tooth brushes arranged to serve as<br />

frames for eyeglasses or a pair of handcuffs<br />

similarly reconstructed. His works are quixotic<br />

and even though they are not intended for the<br />

mass market, they demonstrate an astonishing<br />

creativity that promises a lot to African fashion<br />

and design.<br />

It was an exhilarating<br />

week in Milan. It is obvious<br />

beyond argument that<br />

ideas already exist that will<br />

massage African design<br />

into the 21st century. What<br />

is yet to be developed is the<br />

academic vehicle to expose<br />

them to our design colleges<br />

and technical schools. One<br />

can only hope that this<br />

magazine will land on a<br />

friendly table.<br />

The Milan Design Week was produced by the<br />

City of Milan. The Afrofuture portion was<br />

curated by Nana Ocran and Big Ben.<br />

Left: Cyrus Kabiru’s Artwork<br />

Image from http://www.ckabiruart.daportfolio.com/<br />

16 17

ioGRAPHY<br />

Hugh Masakela is a world-renowned<br />

flugelhornist, trumpeter, bandleader,<br />

composer, singer and defiant political voice<br />

who remains deeply connected at home, while<br />

his international career sparkles. He was born<br />

in the town of Witbank, South Africa in 1939.<br />

At the age of 14, the deeply respected advocate<br />

of equal rights in South Africa, Father Trevor<br />

Huddleston, provided Masakela with a<br />

trumpet and, soon after, the Huddleston Jazz<br />

Band was formed. Masakela began to hone<br />

his, now signature, Afro-Jazz sound in the<br />

late 1950s during a period of intense creative<br />

collaboration, most notably performing in the<br />

1959 musical King Kong, written by Todd<br />

Matshikiza, and, soon thereafter, as a member<br />

of the now legendary South African group,<br />

the Jazz Epistles (featuring the classic line up<br />

of Kippie Moeketsi, Abdullah Ibrahim and<br />

Jonas Gwangwa).<br />

In 1960, at the age of 21 he left South Africa<br />

to begin what would be 30 years in exile from<br />

the land of his birth. On arrival in New York he<br />

enrolled at the Manhattan School of Music.<br />

This coincided with a golden era of jazz music<br />

hugh<br />

and the young Masakela immersed himself<br />

in the New York jazz scene where nightly<br />

he watched greats like Miles Davis, John<br />

Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Mingus<br />

and Max Roach. Under the tutelage of Dizzy<br />

MASAKELA<br />

Gillespie and Louis Armstrong, Hugh was<br />

encouraged to develop his own unique style,<br />

feeding off African rather than American<br />

influences – his debut album, released in<br />

1963, was entitled Trumpet Africaine.<br />

18 19

In the late 1960s Hugh moved to Los Angeles<br />

in the heat of the ‘Summer of Love’, where<br />

he was befriended by hippie icons like David<br />

Crosby, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper. In<br />

1967 Hugh performed at the Monterey Pop<br />

Festival alongside Janis Joplin, Otis Redding,<br />

Ravi Shankar, The Who and Jimi Hendrix. In<br />

1968, his instrumental single ‘Grazin’ in the<br />

Grass’ went to Number One on the American<br />

pop charts and was a worldwide smash,<br />

elevating Hugh onto the international stage.<br />

His subsequent solo career has spanned 5<br />

decades, during which time he has released<br />

over 40 albums (and been featured on<br />

countless more) and has worked with such<br />

diverse artists as Harry Belafonte, Dizzy<br />

Gillespie, The Byrds, Fela Kuti, Marvin Gaye,<br />

Herb Alpert, Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder and<br />

the late Miriam Makeba.<br />

In 1990 Hugh returned home, following the<br />

unbanning of the ANC and the release of<br />

Nelson Mandela – an event anticipated in<br />

Hugh’s anti-apartheid anthem ‘Bring Home<br />

Nelson Mandela’ (1986) which had been a<br />

rallying cry around the world.<br />

In 2004 Masakela published his compelling<br />

autobiography, Still Grazing: The Musical<br />

Journey of Hugh Masakela (co-authored<br />

with D. Michael Cheers), which Vanity Fair<br />

described thus: ‘…you’ll be in awe of the many<br />

lives packed into one.’<br />

In June 2010 he opened the FIFA Soccer<br />

World Cup Kick-Off Concert to a global<br />

audience and performed at the event’s<br />

Opening Ceremony in Soweto’s Soccer City.<br />

In 2010, President Zuma honoured him with<br />

the highest order in South Africa: The Order of<br />

Ikhamanga, and 2011 saw Masakela receive a<br />

Lifetime Achievement award at the WOMEX<br />

World Music Expo in Copenhagen. The US<br />

Virgin Islands proclaimed ‘Hugh Masakela<br />

Day’ in March 2011, not long after Hugh<br />

joined U2 on stage during the Johannesburg<br />

leg of their 360 World Tour. U2 frontman<br />

Bono described meeting and playing with<br />

Hugh as one of the highlights of his career.<br />

Hugh is currently using his global reach to<br />

spread the word about heritage restoration in<br />

Africa – a topic that remains very close to his<br />

heart.<br />

“My biggest obsession is to show Africans<br />

and the world who the people of Africa<br />

really are,” Masakela confides – and it’s this<br />

commitment to his home continent that has<br />

propelled him forward since he first began<br />

playing the trumpet.<br />

Sources/copyright: GRIOT GmbH, Wulf v.<br />

Gaudecker and Hugh Masakela<br />

“The Official Site”<br />

South African trumpeter Hugh Masakela and Nigerian singer Femi Kuti perform during the opening ceremony of the 2010<br />

FIFA World Cup in JOhannesburg. Photo: AFP<br />

20 21

An Interview with<br />

HUGH MASAKELA<br />

poet, philosopher, cultural activist<br />

How many African cities have you visited?<br />

And what are their common features<br />

(in terms of culture, people, design and<br />

architecture)?<br />

I have visited over 30 cities in Africa.<br />

The majority are overcrowded. In most of<br />

them, the impoverished live with very poor<br />

service delivery in sordid squalor and under<br />

extremely unhealthy conditions. Wealthy<br />

countries in Africa have luxurious upper<br />

class neighborhoods, modern malls and<br />

urban development that match Western<br />

metropolises. The most disturbing factor is<br />

that none of the cities boast African-style<br />

designs. Kigali in Rwanda and Windhoek in<br />

Namibia are outstanding for their cleanliness.<br />

Some cities have vibrant cultural groups, clubs<br />

and concert venues. Many countries suppress<br />

the development of cultural excellence,<br />

merely dismissing it as frivolous as it is likely<br />

to upstage the coveted political limelight.<br />

How do you manage to stay current and<br />

topical with the rapid economic changes<br />

engulfing the continent?<br />

Self-education, intense practice, vigorous<br />

physical exercise, playing with outstanding<br />

young musicians and constantly touring the<br />

world.<br />

What are your views on wealth creation<br />

and the creation of a vibrant educated<br />

population who can contribute to<br />

sustainable development and growth of<br />

the continent. Is it really happening?<br />

Most political establishments in Africa<br />

systematically keep the underclass ignorant<br />

and devoid of crucial information that could<br />

help to improve the quality of life. It seems<br />

that wealth creation is limited to the business<br />

and political establishments. Same old, same<br />

old!<br />

I am pessimistic about the development that<br />

is only addressed in summits, conferences<br />

and talk shops but never trickles down to the<br />

masses, who only seem to be noticed when<br />

they are needed for election votes.<br />

22 23

Discuss the rapid growth and<br />

modernization and your thoughts on the<br />

contemporary African city. Could your<br />

experiences in developing hybrid music<br />

genres be an inspiration to how our built<br />

environments could evolve into something<br />

truly African?<br />

Rapid growth in almost all the cities that<br />

experience it, projects imitations of western<br />

metropolises. There is very little if any African<br />

character in them. Perhaps if business and<br />

government could aggressively promote<br />

heritage restoration in the arts; this could be<br />

an element that would inspire African town<br />

planners, designers and architects to project<br />

indigenous styles into our developmental<br />

initiatives.<br />

How has music influenced contemporary<br />

African creative endeavors including<br />

design? What is the link between music<br />

and design?<br />

It appears to me that most<br />

African contemporary music<br />

strives very intensely to imitate<br />

USA and European styles. At<br />

this rate, it is obviously pointing<br />

design and town planning in a<br />

very Western direction.<br />

Unless there is some sort of semblance of<br />

heritage restored into our lives, all the things<br />

we create will suffer from the neo-colonial<br />

frenzy we so extremely try to emulate. There<br />

is no link that I can identify at this writing,<br />

between music and design. African visual<br />

art is the only element that mostly retains an<br />

indigenous quality on our continent, undersupported<br />

as it is.<br />

24 25

What are your views on contemporary<br />

music , culture and how does Africa fare?<br />

Do you see the need for better collaboration<br />

among creatives to promote Africa<br />

globally?<br />

For African culture to have a visible face,<br />

African society is going to have to collaborate<br />

in forming a Heritage Restoration Society<br />

similar to the World Wildlife Fund; an<br />

institute that will aggressively promote and<br />

protect the massive and diverse content of<br />

ancient indigenous qualities whose erosion<br />

we witness by the hour.<br />

How should Africans respond to often<br />

neglected or suppressed heritage and<br />

culture? Is there real interest from Africans<br />

(besides UNESCO and foreign funders)<br />

in preserving some of the unique heritage<br />

of our communities (ie. Sophiatown was<br />

recently renamed back to its original name,<br />

how do we preserve and protect places of<br />

heritage? And does this necessarily mean<br />

becoming political?<br />

I have included a heritage proposal which I<br />

emailed separately in an attempt at illustrating<br />

an example of heritage restoration. It cannot<br />

be preached. It has to be presented through<br />

edutainement. Foreign funders will only come<br />

to the party once the African diaspora begins<br />

to lead. The UN and funders would not know<br />

where to begin.<br />

Discuss current politics on the continent<br />

in the context of north Africa, democratic<br />

reforms and revolutions. What does this<br />

mean for the rest of Africa ?<br />

Until African political leadership ceases from<br />

viewing inaugurations as royal coronations,<br />

we are hurtling down a dangerous path of<br />

power grabs, dictatorships, revolutionaries<br />

who turn into brutal autocrats and academics<br />

who discuss African progress on television<br />

specials, in books and election campaigns. We,<br />

the ordinary people, are hopelessly praying<br />

for “The real thing to come along,” that great<br />

“African dream” we have been hearing about<br />

for the past six decades. When are we gonna<br />

wake up and smell the fufu???<br />

For African culture<br />

to have a visible face,<br />

African society is going<br />

to have to collaborate<br />

in forming a Heritage<br />

Restoration Society similar<br />

to the World Wildlife<br />

Fund; an institute that<br />

will aggressively promote<br />

and protect the massive<br />

and diverse content<br />

of ancient indigenous<br />

qualities whose erosion<br />

we witness by the hour.<br />

26 27

Hugh Masakela & ArchiAfrica present:<br />

competition<br />

THE ROAD TO<br />

HERITAGE<br />

The first Road to Heritage Competition, organized by Hugh Masakela in collaboration with <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong>,<br />

is a ground-breaking design competition in which we seek African designers, students, amateurs and<br />

professionals to present creative and inno-native proposals on how Africans can preserve and promote<br />

our heritage. We seek participants to showcase their ideas in our magazine as well as website, compete<br />

for prize money and bring ideas to the attention of a prestigious jury.<br />

WHY HERITAGE MATTERS<br />

Text by Hugh Masakela<br />

More than 80 % of Africa’s peoples come<br />

from indigenous traditional origins. Our<br />

cultural roots are cultivated in customs, oral<br />

history, praise-poetry, art, design, architecture,<br />

artisanship, agriculture, mysticism, song,<br />

dance, couture, cuisine, pageantry, ceremony,<br />

rituals and moral values. Respect, humility<br />

and generosity have always been the crucial<br />

cornerstones of African life.<br />

Africa’s abundance of unfathomable wealth in<br />

raw materials attracted interest among many<br />

foreign communities. Explorers, militias and<br />

traders began to invade North, West and<br />

Central Africa in the 14th century in search<br />

of treasures. Next came religious groups of<br />

missionaries and prophets with determined<br />

resolve to convert the “natives from barbarism”<br />

and away from their customs. Subsequently<br />

armies and ships laden with superior weaponry<br />

overran most of Africa, confiscating land, food<br />

supplies, and livestock, pillaging and intent on<br />

lording over the indigenous peoples.<br />

Centuries of conquest lead to a merciless slave<br />

trade which saw millions loaded into sailing<br />

vessels that carried Africans to the western<br />

world, a time during which families were<br />

forcibly separated, native languages outlawed<br />

and traditions systematically destroyed.<br />

On the continent, the remaining millions were<br />

colonized. Africa was eventually carved up into<br />

scores of European-created “new” countries.<br />

The native populations were transformed<br />

into legions of cheap-labour armies. Many<br />

converted into Islam and Christianity. Forced<br />

migration to new industrial centres and<br />

farmlands along with minimal education led<br />

to the gradual erosion of traditional heritage.<br />

28 29

Indigenous customs began to disappear:<br />

African civilization saw the evaporation of<br />

our folklore and indigenous origins, which<br />

were gradually abandoned.<br />

By the 21st Century, most Africans (even<br />

though their customs and beliefs were not<br />

totally erased) began to be convinced that their<br />

own heritage was heathen, pagan, backward,<br />

savage, barbaric and primitive due to the<br />

messages created by religion, advertising,<br />

television, misunderstood foreign education<br />

and urbanization.<br />

Today many urban households in Africa<br />

have abandoned communicating in their<br />

mother-tongue. Some even forbid the use of<br />

any language that are not European. Unless<br />

the restoration of heritage into the lives of<br />

Africans is not promoted, future generations<br />

will not define ourselves in our own terms and<br />

words, perhaps claiming that “we used to be<br />

Africans very, very long ago.” This would be a<br />

major tragedy.<br />

This competition is a small means by which<br />

we can re-introduce elements of heritage<br />

restoration into our communities. We do not<br />

seek to preach to the masses, but wish this<br />

competition to use mostly entertainment and<br />

educational methods.<br />

The time has come for us to harness our heritage<br />

and spread it far and wide using modern<br />

technology and all Western civilization has to<br />

offer.<br />

The ideas shared in the competition will<br />

be a most exciting legacy for present and<br />

future generations—not to mention the<br />

foreigners who come to Africa to admire our<br />

geographical sites and wildlife because they<br />

cannot find our people as they are preoccupied<br />

with imitating other cultures. The ancestors of<br />

Africa await this initiative with excited hope<br />

and overwhelming enthusiasm. So does the<br />

rest of humanity. What is now left is to make<br />

it happen!<br />

The competition brief and rules will be published in the<br />

July 2013 issue of the <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>, along with<br />

the members of a prestigious jury and the prize money. The<br />

competition is open to African designers, students, amateurs<br />

and professionals who have ideas on how we can actively<br />

preserve and promote our heritage. The winner of the<br />

competition will be announced at the African Perspectives<br />

Conference in Lagos in December 2013. Winning designs<br />

will be showcased at the conference, as well as on the<br />

<strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> website and <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>.<br />

For more information, please contact Dahlia Roberts at<br />

dahlia@aaaccra.org.<br />

30 31

By RIBA Norman Foster<br />

Travelling Scholar,<br />

Thomas Aquilina<br />

Green<br />

&<br />

Yellow<br />

DIVIDES<br />

ADDIS ABABA<br />

32 33

A travelling research project on informal recycling practices in six African cities (Cairo, Addis Ababa,<br />

Kampala, Kigali, Lusaka, and Johannesburg).<br />

Adane Y., taxi driver, inspected his disposable<br />

photographs meticulously, 6x4 copies slightly<br />

spoiled by a coarse grain and overexposure.<br />

Almost all of them showed the same subject:<br />

a construction site fence painted repetitively<br />

in green and yellow vertical stripes. But with<br />

each image Adane described something<br />

else he saw or intended to capture. When I<br />

pressed him on the reappearing fence, he told<br />

me plainly “it is just in the construction.”<br />

One of my field methods is the distribution<br />

of disposable cameras to residents. These<br />

photographs intend to document a kind of<br />

lived experience and construct a narrative of<br />

each city. With Adane, I asked him to shoot a<br />

typical drive through Addis Ababa. Some of<br />

his photographs were framed by the edge of<br />

his taxi window or dashboard (an old Russian<br />

Lada taxi immaculately kept). His journey<br />

was located between old town, Piazza, and<br />

desirable new location, Bole. In both examples<br />

the fence was there, and provided a clue for my<br />

project. The ongoing investigation – Material<br />

Economies – as part of the RIBA Norman<br />

Foster Travelling Scholarship consists of a<br />

movement (or a line) in each city that follows<br />

the life of a particular material, usually<br />

recycled. This allows me to understand its<br />

arrangement and sequence as it is positioned,<br />

changed or renewed. I trace the intersections<br />

and movements of informal economies, which<br />

take different turns and direct me to different<br />

locations. I encounter a complex interplay of<br />

urban relationships, actors and tactics, mostly<br />

informal and diffuse, and many are invisible.<br />

By following Adane’s implied material, I learnt<br />

that this fence made from corrugated iron<br />

sheeting and always painted with this uniform<br />

colour palette and pattern is a government<br />

regulation in Addis Ababa for every new<br />

building site. A contractor suggested this<br />

directive was a way of “beautifying” the city<br />

before an African Union summit two years<br />

ago. The fence has since become ubiquitous<br />

and shows a city under construction. My<br />

interest, however, is not the aesthetics but<br />

how this canvas is transforming everyday life.<br />

The fencing often encloses large vacant sites<br />

that were once informal settlements. It first<br />

masked a demolished popular neighbourhood,<br />

Filwuha, adjacent to the Sheraton Hotel,<br />

lined with mature palm trees. Residents were<br />

relocated to city-edge condominium plots.<br />

Only a local mafia and handful of surviving<br />

settlers remain. My guide and old Filwuha<br />

neighbour, Biruk G., said it is “just a matter<br />

of time before all old villages are removed<br />

from Addis.” His village will soon be cleared,<br />

and his current stationery business will have<br />

to end. His clients and networks won’t travel<br />

with him and he’s already thinking up a new<br />

occupation as a condominium broker.<br />

Inhabitants in these<br />

environments are readily<br />

repositioned, whether they<br />

are compelled to relocate<br />

livelihoods, or engage in a<br />

form of street occupation.<br />

34 35

In front of the Filwuha fence peddlers<br />

would accumulate and displayed a series of<br />

activities. When a nearby church celebrated a<br />

religious festival priests gave offerings to the<br />

churchgoers at the fence as an overflow service.<br />

Candles, missals, umbrellas, and small plants<br />

were available to buy. Women sold “shameta,”<br />

a local barley juice out of recycled tin cans.<br />

By late afternoon, small stalls populated with<br />

chat-chewers. Chat, fresh evergreen leaves,<br />

a mild narcotic stimulant and lucrative cash<br />

crop. Redressed and punctured with vendor’s<br />

operations the fence becomes the setting for<br />

the stuff of a city to take place.<br />

People use this ambiguous space between<br />

official and unofficial, private and public to<br />

find work. These often-tenuous occupations<br />

result in learned manoeuvres and a constantly<br />

negotiated space, which are sometimes within<br />

original spatial practices. Mobile economies<br />

proliferate; whether it is cellular money<br />

transfers or emerging vendors. Residents are<br />

willing to convert themselves into all kinds<br />

of agents, which reinforces their capacity to<br />

engage with the city, enabling them to grab the<br />

next opportunity, even if they can participate<br />

minimally.<br />

Previous Page (Above): Adane Y.’s disposable photograph<br />

of Bole Road, Addis Ababa<br />

Previous Page (Below): View out from Adane Y.’s taxi<br />

Left: Resident<br />

Below Left: Churchgoers at street corner<br />

Photographs by Thomas Aquilina © 2013<br />

I found myself discovering the kinds of<br />

journeys, daily exchanges and transactions<br />

made by residents within their city. I<br />

followed the relocation of urban majorities<br />

to peripheral condominiums. Across the city,<br />

condominium plot, Gemo, 15-kilometers<br />

from the city centre is where Biruk’s old<br />

neighbour, Atale A., arrived via a ballot<br />

system. Her neighbours drew other plots. The<br />

site is a cluster of insipid and identical fivestorey<br />

buildings with external staircases and<br />

patchy grass open spaces. The phone signal<br />

was unreliable. Atale’s apartment is known<br />

as a “credit home,” and makes a monthly<br />

payment to the government.<br />

The capacity to survive in the old village,<br />

Atale explained, was based on a saturated life.<br />

Where people contributed and divided the<br />

spoils, quick to fill in, substitute and make up<br />

for established relations. Life was grounded; it<br />

took place on the street, where conversations<br />

and networks were shared. In Gemo, this<br />

kind of existence appears no longer workable.<br />

Urban Africans need to invent new solutions.<br />

These narratives focus on the resiliencies of<br />

urban residency in Africa, and with it, the<br />

possibilities. Since travelling it has become<br />

clear the African city is going somewhere, but<br />

it is also always on the point of turning into<br />

something else.<br />

Follow on Twitter @thomasaquilina<br />

36 37

in<br />

of the<br />

SEARCH<br />

ORIGIN<br />

Jurriaan van Stigt<br />

38 39

Since 1980 I have been in love with Mali,<br />

Sudanese architecture, the music of Boubacar,<br />

Toumani and Ali Farka Toure, but in particular<br />

the architecture, culture and anthropology of<br />

the Dogon. It humbles me to write about<br />

what we, at the Foundation Dogon Education<br />

and architect professor Joop van Stigt, have<br />

been able to build in the last 20 years in Mali.<br />

Our inspiration was shaped in the fifties and<br />

sixties when architect Herman Haan, Aldo<br />

van Eyck and others visited the Dogon and<br />

published their experiences in the famous<br />

Dutch magazine FORUM. The publications<br />

in this magazine had a big impact on the<br />

Dutch architectural style at that time.<br />

At this time, Joop van Stigt worked on the<br />

building site of the Orphanage designed by<br />

Aldo van Eyck in Amsterdam. Van Eyck sent<br />

him a postcard with a picture of Djenne- and<br />

on the back was this text and a fast drawing of<br />

his design of the building with small cupolas.<br />

(Picture of front and backside of the postcard,<br />

and translation of the text… will be the first<br />

time ever this is published) Back in the<br />

Netherlands, the building was constructed as<br />

it stands now with a characteristic honeycomb<br />

dome-vaulted structure, which is still famous<br />

and considered part of Dutch heritage. The<br />

orphanage symbolizes a big opportunity<br />

in thinking about scale. It was the start of<br />

thinking in structure: the city as house, a house<br />

as a city, inside and outside, the big scale and<br />

the small scale. In the Orphanage, there is a<br />

realization of a duality in every task: there is<br />

a visible cellular structure, but also freedom.<br />

Previous Page: Dogon, Bandiagarra Cliffs<br />

Left: FORUM magazine<br />

It is this theme that van Eyck found so<br />

intriguing in the Dogon so many years ago.<br />

The experience described was van Stigt’s first<br />

encounter with Mali and became a motivation<br />

to go there himself. He made his first trip to<br />

Mali in 1972, and has kept going ever since.<br />

After his retirement as professor in Delft<br />

specialized in building constructions, heritage<br />

and renovation, he presented his book Dogon<br />

Architecture, Art and Anthropology and<br />

started the Foundation Dogon Education.<br />

The first aim was not to make “architecture,”<br />

but to create wells, water supplies and school<br />

buildings. Throughout the years, the experiences<br />

grew into much more than simply building;<br />

he learned to work with the Dogon people,<br />

exchange knowledge and experiment with<br />

new techniques. By analyzing the extremely<br />

ingenious adobe construction methods of the<br />

Dogon, it was possible to further develop his<br />

imported methods in order to be able to build<br />

in a sustainable way with locally available<br />

materials. The mantra of building in Dogon<br />

became “pas simple, pas bon” (not simple not<br />

good) and stayed as a theme of van Stigt in<br />

his work in the Netherlands where he became<br />

known for looking for the most economical<br />

solution combined with a clear, simple and<br />

true beauty of the building. It can be argued<br />

that he learned this skill from the Dogon and<br />

Sudanese mud architecture.<br />

40 41

“Everything from mud and some wood!<br />

Wonderful World! We are a bit white -<br />

healthy feeling however. Nowhere have<br />

I laughed so much and making jokes.<br />

Every morning a whole pineapple!<br />

Delicious Mangoes. Niger fish and<br />

chicken. Hot – beautiful birds, women<br />

and towns (will show slides and film).<br />

Tomorrow begins the big hike along the<br />

Dogon gap with intact primeval culture.<br />

Donkeys carry the stuff – It is fine with<br />

my now-no-care-child.<br />

“<br />

I’m 27 on the construction site, brown,<br />

--- and ready for new steps.<br />

Don’t forget a Santa Claus gift hi hi hi<br />

AvEyck<br />

42 43

In 2008 the Fondation started to build with<br />

hydraulic compressed earth blocks, a next step<br />

in the continuation of the traditional adobe<br />

building methods in the Dogon, (see the book<br />

‘beyond construction’). The decision to do so<br />

responded to a need for the architecture to fit<br />

into the landscape and connect to the culture.<br />

Our first buildings using this method were in<br />

Sevaré, and included housing, extension of the<br />

technical school and a small hotel. Everything,<br />

including bearing walls and facades of<br />

half brick (14 centimeter) were built with<br />

earth blocks, even carrying concrete floors<br />

and overstrains of 7 meters. The buildings<br />

are located in the new town which houses<br />

modern Malian housing, architecture, some<br />

old French colonial architecture, all of which<br />

are strongly influenced by the Sudanese style.<br />

The most important objective here was to learn,<br />

build and show that there is a natural beauty<br />

in building with earth. The information centre<br />

of mud architecture in Mopti built by the Aga<br />

Khan Foundation designed by Francis Kéré<br />

was in this case a great support for changing<br />

the mind set in building methods. Now there<br />

are a lot of new skilled builders in the region<br />

of Mopti Sevaré which will hopefully give a<br />

boost to build, construct and design a truly<br />

sustainable Malian architecture by local<br />

architects and masons.<br />

With the experience of knowledge we gained<br />

in Sevaré, the Fondation started building<br />

more primary schools in the Dogon area<br />

with compressed earth blocks. The villages all<br />

require a different approach depending on their<br />

location along the cliffs of Bandiagarra, the<br />

plain or the plateau. However, every building<br />

the Fondation constructed throughout the<br />

years was realized with the strong support and<br />

contribution of a village who prepared sand,<br />

red earth and water.<br />

In 2012 the first school complex, three<br />

school classrooms, housing for teachers and<br />

sanitation with barrel vaults was completed.<br />

This complex near the village of Balaguina,<br />

on the plateau one hour’s drive from Sevaré,<br />

is almost 100% earth bricks (excluding<br />

the concrete foundation). The bricks were<br />

produced on site by transporting a brick<br />

machine to the location. The buildings rise<br />

literally out of the earth from which they are<br />

made. The village has contributed immensely<br />

to the production of the bricks on the site.<br />

The school is designed with two verandas,<br />

which can be seen as the buttress to the barrel<br />

vaults above the classrooms. Each classroom<br />

is dilated, the roof is constructed with brick<br />

masonry on its side. The <strong>final</strong> layer of the roof<br />

is finished with 4 centimetres of red earth and<br />

a little (5%) cement.<br />

Previous Page: Postcard from Aldo van Eyck<br />

Inset: Renovation, primary school in Sangha 1907<br />

Next Page: Internship project students of the Technical<br />

School (ETSJ), February 2012<br />

44 45

46 47

In 2012 the first school complex, three<br />

school classrooms, housing for teachers and<br />

sanitation with barrel vaults was completed.<br />

This complex near the village of Balaguina,<br />

on the plateau one hour’s drive from Sevaré,<br />

is almost 100% earth bricks (excluding<br />

the concrete foundation). The bricks were<br />

produced on site by transporting a brick<br />

machine to the location. The buildings rise<br />

literally out of the earth from which they are<br />

made. The village has contributed immensely<br />

to the production of the bricks on the site.<br />

The school is designed with two verandas,<br />

which can be seen as the buttress to the barrel<br />

vaults above the classrooms. Each classroom<br />

is dilated, the roof is constructed with brick<br />

masonry on its side. The <strong>final</strong> layer of the roof<br />

is finished with 4 centimetres of red earth and<br />

a little (5%) cement.<br />

For light and ventilation, we used locally<br />

produced ceramic gargoyles. It gives the school<br />

building it’s architectural recognition. The<br />

porches of the veranda’s are inspired by the<br />

particular way openings and facades are made<br />

in several Sudanese style buildings. The floors<br />

are also made of earth blocks but instead of the<br />

normal 8.5 kilo bricks (90*140*290) we made<br />

them 5 kilo to reduce the use of material and<br />

cement. In every brick, we used 3% cement<br />

mix to make the blocks water resistant and<br />

termite proof.<br />

The houses for the teachers and head master<br />

are positioned along the road and near the<br />

well. The basic houses are each orientated in<br />

a different direction to obtain privacy. This<br />

architecture is more inspired by the plasticity<br />

of the architecture of the granaries, houses<br />

and Ginna’s of the Dogon.<br />

Left: Atelier of the Technical School (ETSJ) in Sévaré<br />

48 49

There are two main issues that had to<br />

be reconciled with building modern<br />

buildings such as schools using<br />

traditional Dogon architecture.<br />

Firstly, in Mali and especially in<br />

the Dogon area, cellular buildings<br />

with small sized spaces are the most<br />

common type architecture and part<br />

of the traditional building method.<br />

Even Mosques are bigger buildings<br />

on the exterior, but on the interior<br />

are still divided into small spaces<br />

with small spans. The second issue<br />

is the position of the schools and<br />

housing for teachers in relation to<br />

the village. The school buildings are<br />

a clearly different size, scale and<br />

structure. In contrast to the Dogon<br />

tradition which says one’s village<br />

is one’s home, the Foundation built<br />

outside the villages. On the one<br />

hand this exclusion from the village<br />

gives freedom to architecture, but<br />

on the other hand it demands reestablishing<br />

a connection to the<br />

genius loci. The first school of the<br />

foundation was built using building<br />

methods already common for<br />

school buildings throughout Mali,<br />

and became very utilitarian. The<br />

challenge in the future is to adapt<br />

these issues and respond to them<br />

more directly.<br />

Inset: House Hogan Arou<br />

50 51

Above: Traditional method mud block<br />

Below: Ensemble of the primary school in Balaguina<br />

Above: Overview of 15 years of work by the Foundation<br />

Education Dogon Jurriaan van Stigt, “Beyond<br />

Construction,” 2012<br />

The book beyond construction,(plus que construire) can<br />

be ordered through the internet book publisher www.<br />

Pumbo.nl<br />

Below: Detail of a saho at Bia, near Niafunké Sergio<br />

Domain, “Architecture Soudanaise,” 1989<br />

There will be a fenced area around the houses<br />

with hangars for the kitchen. The school<br />

started in October 2012 after a very rainy wet<br />

season, which proved that the construction<br />

without a ‘raincoat’ is sustainable. Also<br />

the interior climate due to the use of the<br />

compressed earth blocks is very pleasing.<br />

The process I have described to the readers<br />

of <strong>ArchiAfrika</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> continues, as there<br />

is still a lot to be learned in the future. We<br />

hope that our buildings inspire and motivate<br />

more and more of the upcoming builders and<br />

architects from Dogon. Architecture is not<br />

about revolution but about evolution.<br />

Jurriaan van Stigt<br />

Chair Foundation Dogon Education<br />

Architect at LEVS architecten<br />

Chief editor FORUM <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Information<br />

www.dogononderwijs.nl<br />

52 53

CAIRO<br />

URBANISM<br />

tra$h becomes ca$h<br />

Zeina Elcheikh<br />

A group of 21 students from Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Tunisia and<br />

Germany converged in Basateen district in Cairo in the informal area<br />

of Ezbet Al-Nasr to think about design analysis including basic urban<br />

services, local economic development, land and shelter, governance,<br />

and environment. An exhibition of their proposals in February 2013<br />

selected the initiative of three students: Nahla Makhlouf (Egypt),<br />

Sandy Qarmout ( Jordan) and Zeina Elcheikh (Syria) to implement as<br />

a means of addressing the garbage problems in the neighborhood.<br />

54 55

Garbage is almost everywhere in the area.<br />

The huge amount of trash was causing<br />

serious health problems, originating from<br />

the natural degradation of organic waste or<br />

from burning it, which is usually the only<br />

way to get rid of it. Some of the residents<br />

collected and sorted wastes through a<br />

recycling micro industry, including metal,<br />

plastic, cartoons, glass recycling. However,<br />

there was no way of recycling organic wastes.<br />

The people in Ezbet Al-<br />

Nasr represent a low-income<br />

community, and the three<br />

students agreed upon developing<br />

a concept that involves garbage<br />

to solve an environmental<br />

problem but also to provide<br />

additional income. They came up<br />

with the motto: “Trash Becomes<br />

Cash”.<br />

Contacts were made with several NGOs<br />

and individuals interested in recycling and<br />

environmental issues. Getting to know better<br />

about professionals’ work in these fields in<br />

Cairo, helped in framing the work of the<br />

team. The students decided to introduce<br />

biogas to the residents of Ezbet Al-Nasr.<br />

Each biogas unit costs between 180-200$,<br />

an amount not easily affordable by the local<br />

community, and therefore funding was needed<br />

to install the units. Generous support came<br />

from an association (Al-Musbah Al-Mudii)<br />

which offered to fund the first 5 biogas units<br />

at no cost and to financially support interested<br />

people in the area in installing their biogas units<br />

in the future. Two technicians also provided<br />

technical support, as they had installed biogas<br />

units in their own homes a few years ago.<br />

56 57

The residents of Ezbet Al-Nasr needed to<br />

rethink their garbage-related habits and<br />

practices, and to consider it as an income<br />

source to be used rather than a leftover<br />

to be thrown away. Such a task was not<br />

easily achieved without approaching the<br />

local community directly through informal<br />

meetings and discussions on the streets. While<br />

installing the first biogas in the area, the team<br />

arranged a session to introduce the idea to the<br />

local residents. This session to raise awareness<br />

about biogas was held under the theme “Let’s<br />

not throw it, let’s make use of it.”<br />

During the exhibition the Trash Becomes<br />

Cash team prepared and distributed manuals<br />

and other printed materials to spread the<br />

idea and established a network between the<br />

community, the funding agency and the<br />

technicians involved in this new microindustry.<br />

Although the team achieved satisfactory<br />

results by introducing the residents to a<br />

new sustainable technology, the continuity<br />

of the project depends on the community’s<br />

acceptance of the technology in the long run.<br />

It can be a big step to begin reconsidering<br />

organic waste as a resource that can help save<br />

the residents money, rather than just garbage.<br />

But this initiative may be a first step in the<br />

right direction.<br />

Informal settlements suffer from<br />

many challenges associated with<br />

the built environment. Bridging<br />

academic research to realworld<br />

practice, and technology<br />

with socio-economic needs of<br />

the community was the main<br />

outcome of the intervention.<br />

Above: Illustration of the Biodegradable process from the<br />

organic waste to the Biogas<br />

Left: Garbage in Ezbet Al-Nasr<br />

Below Left: Schematic cross section in the applied<br />

biogas unit (developped by the team based on the site<br />

implementation)<br />

Next Page: Installing the 1st Biogas Unit<br />

Photos courtesy of Zeina Elcheikh<br />

58 59

The project showed that<br />

big hopes in the informal<br />

area can be fulfilled<br />

through seemingly small<br />

initiatives<br />

60 61

the real<br />

ECONOMY<br />

Informal Housing, Work and The Future<br />

A look at Accra and Lagos<br />

By Gilbert Nii-Okai Addy<br />

Gilbert Nii-Okai Addy manages a globetrotting work and lifestyle portfolio as (1) an International<br />

Economist and Management Consultant ; (2) a Critic , Writer and Historian of the Arts, Culture and<br />

Creative Industries and (3) a Classical Guitarist<br />

You may follow him on Twitter at : https://twitter.com/gnaddy<br />

62 63

Just about everybody living in African cities<br />

like Accra and Lagos is connected in some<br />

way with the informal economy. Nearly<br />

everybody has bought something from a street<br />

seller. One only has to walk or drive around<br />

Accra or Lagos for a short time to discover<br />

that the vast majority of people work in the<br />

informal (unregistered) economy. More and<br />

more people are moving from the rural areas<br />

into the towns and cities, attracted by the<br />

prospect of work selling various goods and<br />

services beauty salons, tailoring, street selling.<br />

In West Africa the increasing adoption of<br />

the ECOWAS trade liberalization protocols<br />

involving the movement of goods and people<br />

means that more and more of this rural-urban<br />

migration will in fact be of a cross border<br />

nature.<br />

One of the biggest political and economic<br />

tasks facing Ghana is how to recalibrate its<br />

relationship with Nigeria over the coming<br />

years.<br />

This is essentially the<br />

relationship between Accra<br />

and Lagos anyway since<br />

both cities account for over<br />

60% of their national<br />

economies. This year 2013<br />

is in fact a pivotal year in<br />

economic terms for the city of<br />

Lagos, Nigeria as a country<br />

and West Africa.<br />

Here are just three of the many interesting<br />

and even surprising economic facts about<br />

Lagos and Nigeria:<br />

1. Lagos is projected to overtake Cairo as the<br />

biggest city in Africa.<br />

2. The economy of Lagos is now bigger than<br />

that of all of Kenya.<br />

3. The economy of Nigeria, for all its chaos and<br />

dysfunctionality, at current rate of growth, is<br />

projected to overtake that of South Africa as<br />

the biggest in Africa by 2015.<br />

4. The Greater Ibadan-Lagos-Accra (GILA)<br />

Corridor: This 600-kilometer (373-mile)<br />

transport and economic corridor growing<br />

agglomeration of cities runs through four<br />

countries—Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and<br />

Ghana—and comprises the economic engine<br />

of West Africa.<br />

For most of modern history, Africa’s economic<br />

landscape has been dominated by the North<br />

(North Africa) and the south (mainly south<br />

Africa) and the tropical middle was the<br />

poorest part. In recent years, however, the<br />

centre of gravity has been shifting - or in fact<br />

has shifted already - to its tropical middle.<br />

What has been taking place quietly has been<br />

dubbed by some as the economic rise of<br />

Tropical Africa.<br />

Above: A child sells fried dough to other children. Badia residents were bewildered that their government had apparently<br />

declared open season on them. “They are doing this without regard for the people who live here,” Felix Morka said of the<br />

government-led demolitions. Image Credit: Samuel James for The New York Times.<br />

Previous Page: Lagos Sprawl. Image Credit: Keji Ziza - http://www.flickr.com/photos/76902663@N00/1463999464/<br />

Economic growth in much of Africa has<br />

defied both expectations and the scourge<br />

of “Afro-pessimism” that was rampant for<br />

so long among both some Africans and the<br />

continent’s detractors. But Africa’s economic<br />

recent growth, impressive as it may be, has<br />

not been accompanied by any significant job<br />

creation and increasing population growth.<br />

Furthermore, urbanization has not been<br />

accompanied by industrialization that would<br />

transform our economies. It has largely been<br />

a phenomenon of “jobless growth.” The<br />

rate or urbanization – the influx of people<br />

from rural areas into towns and cities, has<br />

been unprecedented in human history.<br />

Several countries like Ghana have seen their<br />

populations go from being predominantly<br />

rural to predominantly urban, in just a single<br />

generation. The massive urbanization has seen<br />

the explosive growth of informal settlements<br />

with all kinds of catchy names – slums, ghettos,<br />

shanty-towns. The lack of formal sector jobs<br />

has led to the relentless growth of the informal<br />

economy and informal jobs. The reality is that<br />

today, most African countries have largely<br />

informal economies with the informal sector<br />

accounting for over 70-80% of the economy.<br />

Much of the economic growth taking place<br />

in Africa is actually in the informal rather<br />

than formal sectors and this trend is likely to<br />

continue over the foreseeable future. There<br />

is also likely to be an unstoppable growth<br />

in poor informal urban settlements whether<br />

the political establishment and the relatively<br />

affluent minority like it or not.<br />

64 65

Inset: Market. Image Credit: Sean Blaschke<br />

66 67

Above: London Victorian slum - Kensington. Image Credit: Gilbert Nii-Okai Addy<br />

The well publicized “slum clearance” and “city<br />

decongestion” initiatives have not yielded any<br />

measurable or long lasting success. The New<br />

York Times in March 2013 had an interesting<br />

feature article about the bulldozing of a<br />

long-established informal settlement by the<br />

authorities in Lagos and wondered whether<br />

the city’s poor were being made to pay a heavy<br />

price for the city’s “progress”. The article is<br />

accessible at:<br />

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/02/world/<br />

africa/homeless-pay-the-price-of-progress-inlagos-nigeria.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0<br />

There is a need for debate on what to do about<br />

slums or, to use the more polite term, informal<br />

settlements. In Africa given the current rates<br />

of urbanisation and population growth which<br />

are unprecedented in human history, slums<br />

are a necessary process of urbanisation. It is<br />

estimated by economists that more than half<br />

the world’s people now live in “slum” areas of<br />

cities and work in the informal economy.<br />

There is a need for debate<br />

on what to do about slums<br />

or , to use the more polite<br />

term, informal settlements,<br />

in Africa given the current<br />

rates of urbanisation and<br />

population growth which<br />

are unprecedented in<br />

human history anywhere in<br />

this world. Slums always<br />

accompany the process<br />

of urbanisation. It is<br />

generally estimated by many<br />

economists that more than<br />

half the world’s people now<br />

live in “slum” areas of cities<br />

and work in the informal<br />

economy.<br />

68 69

Above: London Victorian slum children. Image Credit: Gilbert Nii-Okai Addy Image Credit: Sean Blaschke<br />

Much of nineteenth century London was<br />

made up of slums, as anyone who ever read<br />

Charles Dickens would imagine or know.<br />

It was the same with New York and other<br />

American cities. Many Indian cities like<br />

Mumbai and Calcutta are mostly slums,<br />

depending on how one defines a slum and the<br />

numbers and living conditions of the people<br />

living there.<br />

In London for instance the great 19th century<br />

slum clearances like what we are seeing in<br />

Lagos, never really solved the problem. The<br />

slums and slum dwellers just shifted to other<br />

geographical areas like St Giles, and newer<br />

slum areas like Bermondsey, Brixton and<br />

others. In fact the poorer parts of London<br />

today very much have their roots and origins<br />

in the Dickensian slums of the Victorian era.<br />

The political and intellectual lexicon may have<br />

changed with the times, as has the economy<br />

and the provision of social housing, but the<br />

underlying socio-economic dynamics are still<br />

there. There is still a constant debate about<br />

issues like urban regelation, poverty and social<br />

deprivation in places like the East End of<br />

London, Tower Hamlets, Brixton, Peckham<br />

and others. Immigration from non-European<br />

parts of the world since the end of the second<br />

World War have added issues of race and<br />

ethnicity into the equation, but basically the<br />

issues are about human beings trying to make<br />

a living in an urban environment with a highly<br />

unequal access to economic and political<br />

power.<br />

In Africa these issues are compounded by<br />

the fact that, almost uniquely in economic<br />

history, we have been witnessing urbanisation<br />

on an unprecedented scale without much<br />

industrialisation. This is the main reason for<br />

the economic dominance of the informal<br />

sector in most of urban modern Africa. A<br />

largely informal economy necessarily goes<br />

hand in hand with a largely informal housing<br />

infrastructure.<br />

What is happening in Lagos is happening all<br />

over Africa including South Africa and our<br />

own Ghana. Ever heard of Accra’s Sodom<br />

and Gomorrah and the City Mayor’s almost<br />

weekly attempts to get street traders out of<br />

the city centre? The trouble though is that<br />

slums and slum dwellers never go away. The<br />

politicians and town planners- or village idiots<br />

as some cynically call them- often seem to get<br />

it wrong. They thought they would escape<br />

Lagos by building Abuja in the 1970s and<br />

now Abuja itself is becoming or has become a<br />

majority slum city!<br />

Most of Accra and Kumasi, our two main urban<br />

centres, are mostly slums. Even the pockets<br />

of affluence we have are under relentless<br />

pressure from the surrounding slums. If not in<br />

terms of people then certainly in terms of the<br />

now almost permanent water and electricity<br />

crises which are a direct result of the explosive<br />

growth in the city’s population from around<br />

200,000 at independence to over 4 million<br />

today - in just over 50 years.<br />

70 71

Image Credit: Sean Blaschke<br />

Some projections have it that in around 20<br />

year’s time, nearly 50% of Ghana’s entire<br />

population could be living in the Greater<br />