You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

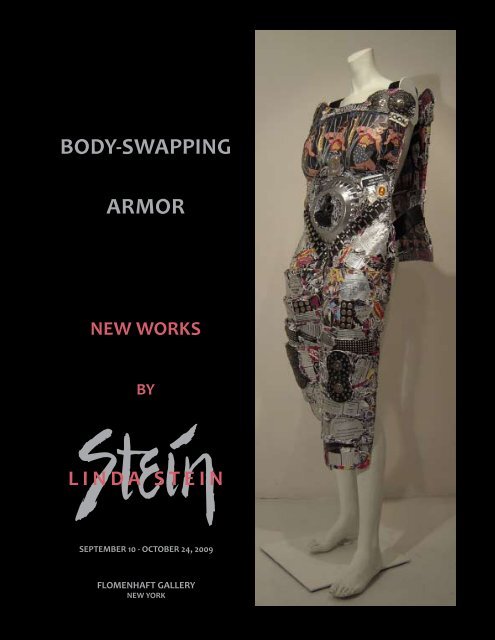

<strong>BODY</strong>-<strong>SWAPPING</strong><br />

<strong>ARMOR</strong><br />

FRONT COVER: FIG. 1. KNIGHT OF TOMORROW 542. 2005. WOOD, METAL, STONE. 80” X 24” X 17” SIEMENS COLLECTION<br />

IN THE PROCESS OF BEING CONVERTED TO BRONZE IN A LIMITED EDITION<br />

ABOVE: FIG. 2. SELF PORTRAIT WITH BLADES 197. 1993. PHOTO MONTAGE. 8” X 10”<br />

FRONT COVER: FIG. Heroic Compassion 665. 2009<br />

wood, metal, paper, and mixed media. 65" × 18" × 14" on mannequin<br />

NEW WORKS<br />

BY<br />

LINDA STEIN<br />

SEPTEMBER 10 - OCTOBER 24, 2009<br />

FLOMENHAFT GALLERY<br />

NEW YORK

FRONT COVER: Fig. 1. Heroic Compassion 665. 2009.<br />

wood, metal, paper, and mixed media. 65" × 18" × 14"<br />

THIS PAGE: Fig. 2. Power 581. 2007.<br />

wood, metal, stone. 48" × 16" × 8"<br />

<strong>BODY</strong>-<strong>SWAPPING</strong>, EMPOWERMENT AND EMPATHY:<br />

LINDA STEIN’S RECENT SCULPTURE<br />

By Margo Hobbs Thompson 1<br />

As she concluded her May 2009 keynote address to the National Association<br />

of Women Artists, <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> remarked, “Gender constructions and gender<br />

constrictions. How do we find the courage, the bravery to break these<br />

molds?” 2 Her series of Knights, begun in 2002, guides the viewer toward<br />

empowerment in the face of sexism, homophobia, racism, and other<br />

forms of institutionalized oppression. Since 2007, the Knights have<br />

evolved from static totemic personages mounted on the wall to<br />

suits of armor animated by their wearers. They are trickster figures<br />

in their shape-shifting potentialities. <strong>Stein</strong> encourages the viewer<br />

to imagine what it is like to slip into another skin, to swap bodies<br />

and shift genders.<br />

The oldest work on view, Knight of Wishing 557 [fig. 3] is an excellent<br />

example of the hieratic figures <strong>Stein</strong> made to hang on the wall, like<br />

guardians. As it did for so many, the destruction of the World Trade<br />

Center towers on September 11, 2001 had a profound effect on<br />

<strong>Stein</strong>, whose studio was within earshot of the planes exploding<br />

and who ran north, holding hands with her studio assistants, to<br />

escape what she feared was a bomb attack. She witnessed the<br />

towers’ collapse. In the aftermath of that day, Adorno’s remark<br />

about the barbarity of writing poetry after Auschwitz seemed newly<br />

relevant; 3 <strong>Stein</strong>, like others in the fine arts and literature, found it<br />

difficult to resume her creative work and did not make sculpture for a<br />

year afterwards. When she returned to the studio, she discovered that<br />

she no longer worked abstractly, but sculpted vertical forms that were<br />

figurative and undeniably, if unintentionally, feminine. She has explored<br />

and refined these guardians or shields in the years since in a dialectical<br />

process in which every work answers some formal or philosophical<br />

questions while it poses new ones. Power 581 [fig. 2] and Knight of Wishing<br />

557 [fig. 3] look as though they have been salvaged from a ruined site,<br />

formed out of urban debris fused by intense heat and compression. The hard<br />

surfaces of the embedded metal and stone bring to mind the trinitite produced<br />

when New Mexico sand melted under the force of atomic test blasts, or the<br />

petrified relics of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The dense conglomeration of material<br />

makes these figures heavy and impenetrable, like a suit of armor—hence Knights.<br />

Fig. 3. Knight of Wishing 557. 2006. wood, metal, stone, leather. 48" × 16" × 6"<br />

2 3

4<br />

Figs. 4-6. Knight at Ease 652. 2009. wood, metal, leather,<br />

paper, archival inks plus velcro straps. 46" × 17" × 10"<br />

More recent works, such as Knight at Ease 652<br />

[figs. 4-6] and Heroic Compassion 665 [fig. 1,<br />

front cover], are meant to be worn, with divided<br />

articulated legs and adjustable Velcro straps [fig. 7].<br />

They still resemble armor, but for mobile samurai<br />

warriors 4 , not medieval gallants. The materials are<br />

densely packed and incorporate elements that<br />

demand to be read and decoded: found security<br />

badges and an Asian deity in Heroic Compassion,<br />

and comic strips and commercial texts in Knight<br />

at Ease. The dominant iconography is feminine:<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> incorporates images of the DC Comics<br />

hero Wonder Woman and the anime Princess<br />

Mononoke. But on the whole, these suits of armor<br />

are androgynous; as Jann Matlock observed in her<br />

2007 article on <strong>Stein</strong>, armor situates the wearer<br />

outside expected gender categories—Joan of Arc,<br />

for example, was unwomanly but not masculine in<br />

her armor. 5 <strong>Stein</strong> enhances this gender ambiguity<br />

by making the Knights’ waists slender but not<br />

hourglass shaped, and their pectorals prominent<br />

but not breast-like. Their pubic areas offer no<br />

clues. 6<br />

Fig. 7. Interactive performance with Pilobolus Dancer,<br />

Josie M. Coyoc, and others moving to music wearing<br />

Knights at <strong>Stein</strong>’s NAWA exhibition in 2009<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> takes gender seriously, as an artist and as an<br />

activist. In this regard, her work bears comparison<br />

with some of the feminist artists whom curators<br />

and art historians have recently reconsidered in<br />

Figs. 8-9. <strong>Stein</strong> channels Wonder Woman and<br />

imagines her thoughts in today’s world<br />

exhibitions such as WACK! Art and the Feminist<br />

Revolution and Global Feminisms. 7 Printmaker<br />

and installation artist Nancy Spero, for example,<br />

made a commitment in the mid-1970s to picture<br />

only female figures and to represent women as<br />

protagonists. Like Spero, <strong>Stein</strong> is interested in<br />

female empowerment and she references feminine<br />

archetypes. She is more concerned than Spero,<br />

however, in exploring the borders and limits that<br />

define gender: its construction and constraints.<br />

Dara Birnbaum’s 1978 video, Technology/<br />

Transformation: Wonder Woman seems at first<br />

to share, if not predict, <strong>Stein</strong>’s fascination with<br />

the female super-hero. But Birnbaum’s work—of<br />

which <strong>Stein</strong> was until recently unaware—is above<br />

all a critique of the mass media’s objectification<br />

of women, and she neither liberates the media<br />

icon nor explores the archetype she represents.<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> locates Wonder Woman’s value as a role<br />

model, and through her examines her own<br />

Fig. 10. Another example of remarks that<br />

Wonder Woman might currently hear<br />

5

6<br />

artistic project. As a life-long pacifist, <strong>Stein</strong><br />

was discomfited to recognize that her figurative<br />

sculptures were warriors especially in the context<br />

of the masculinization of the so-called war on terror<br />

that escalated after 9/11. Wonder Woman offered<br />

an alternative: she was a defender of those who<br />

needed her protection without being bellicose.<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> adapted other heroines in her pantheon<br />

of strong and benevolent protectors: the Asian<br />

goddess of mercy Kannon or Kuan-yin (referred<br />

to by several different names, and who in some<br />

cultures is both man and woman) who answers<br />

all appeals and alleviates suffering, and the anime<br />

Princess Mononoke (from the 1997 film by Hayao<br />

Miyazaki) who was raised by wolves and fights on<br />

the side of the animals against human destruction<br />

of her beloved forest [fig. 11]. <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights are not<br />

just symbolic guardians in the uneasy, post-9/11<br />

world: they articulate new gender positions where<br />

strength and mercy do not belong exclusively to<br />

one sex or the other.<br />

Wonder Woman’s creator set himself a similar<br />

task in 1941 when he imagined his heroine<br />

as both strong and alluring. William Moulton<br />

Fig. 11. <strong>Stein</strong> with her favorite icons:<br />

Wonder Woman, Mononoke, and Kannon<br />

Marston drew upon Greek mythology for his<br />

Amazon princess, whom he endowed with<br />

attributes belonging to goddesses, gods, and<br />

heroes: Athena’s wisdom, Aphrodite’s beauty,<br />

Hermes’ fleetness, and Herakles’ strength. She<br />

leaves the land of the Amazons, Paradise Island,<br />

with her bullet-deflecting bracelets, invisible<br />

telekinetic plane, and golden lasso of obedience<br />

(later the lasso of truth) to bring peace and justice<br />

to the world of men. 8 An important contradiction<br />

informs Wonder Woman’s genesis, which Kelli E.<br />

Stanley explores in her 2005 analysis of the comic<br />

book super-hero. Female warriors were forbidden<br />

in patriarchal cultures like ancient Greece, yet<br />

the mythical Amazon was adopted to legitimize<br />

Athenian authority; the Amazon, who in her very<br />

nature was opposed to patriarchy, was the Other by<br />

and through which the patriarchy defined itself. The<br />

latter-day Amazon Wonder Woman, at once taboo<br />

and desired, metamorphosed over the decades<br />

“to reflect nothing less than the confusion, fear,<br />

and constant reformation of American ideals about<br />

American women” according to Stanley. 9 As <strong>Stein</strong><br />

has mobilized her once more, we might ask what<br />

Wonder Woman signifies in the post-9/11 age, what<br />

ideals of American womanhood she reflects. How<br />

does she embody these ideals, and to what extent<br />

does she subvert them?<br />

In <strong>Stein</strong>’s hands, Wonder Woman advances the<br />

artist’s intention to recognize feminine strength<br />

and valor that are disavowed in the masculine<br />

and feminine positions that structure our society.<br />

<strong>Stein</strong>, in her NAWA address and elsewhere,<br />

speaks movingly of the way gender stereotypes<br />

were reified after 9/11 in the media and official<br />

discourse to make all the heroes men (soldiers<br />

and first responders), and the victims women (the<br />

9/11 widows most prominently). Fundamentally,<br />

<strong>Stein</strong>’s recent art is about disturbing the binaries<br />

that organize our society and that we accept<br />

unquestioningly as natural. The masculine and<br />

feminine polarities that she investigates are easily<br />

mapped onto other structuring dichotomies in<br />

which each term has gender connotations: public<br />

and private, culture and nature, mind and body.<br />

This last is a compelling pair to consider for its<br />

philosophical implications, an argument Elizabeth<br />

Fig. 12. Detail of Breaking News 638<br />

Fig. 13. Breaking News 638. 2008. paper,<br />

archival inks, wood. 78" × 24" × 11"<br />

7

8<br />

Grosz develops in her book Volatile Bodies. For<br />

Grosz, the body and gendered subjectivity are<br />

tightly interlinked in all fields of knowledge. 10<br />

She calls for a complete rethinking of the body<br />

that would acknowledge its centrality to cultural<br />

and subjective formations and predicts the<br />

repercussions: “developing alternative accounts<br />

of the body may create upheavals in the structure<br />

of existing knowledges, not to mention in the<br />

relations of power governing the interactions<br />

of the two sexes.” 11 In short, Grosz believes<br />

that reconceptualizing the body will lead to the<br />

realization that the masculine/feminine relationship<br />

is complex and mutually implicated, not a polarized<br />

binary and that this in turn will undermine the<br />

patriarchal system that places constraints on<br />

women and men, and their bodies, alike. 12 Grosz<br />

sketches a set of considerations and concerns that<br />

attend a feminist rethinking of the body, and several<br />

of these help to illuminate <strong>Stein</strong>’s project.<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> explores “embodied subjectivity” with her<br />

wearable Knights, a term Grosz favors because<br />

it stresses the interdependence of the mind and<br />

body. 13 The Knights stage an experience of the<br />

tight connection between mind and body: wearing<br />

one, the viewer may find herself suffused with<br />

a new consciousness that originates in the new<br />

body she has taken on. This new sensation is<br />

dramatically recorded in the videotapes <strong>Stein</strong> has<br />

made of visitors to her studio trying on various<br />

Knights. 14 A man wearing W 629 reported, “I feel<br />

stronger … I feel more of a sense of power. I feel<br />

like I’m protected and safe.” Another man wearing<br />

the same piece expounded, “Wow, I feel like a<br />

pregnant woman” as he caressed the swelling<br />

metal belly of the sculpture. “I feel like I’ve got a<br />

really big womb … like an earth mother” [fig. 14].<br />

Jann Matlock and Ann V. Bible have both written<br />

about the haptic quality of <strong>Stein</strong>’s sculpture. 15<br />

Art historian <strong>Linda</strong> Nochlin associated a haptic,<br />

or touch-based approach to space with art by<br />

women. 16 More provocatively, film historian Laura<br />

U. Marks advanced a concept of “haptic visuality”<br />

to describe a feminist mode of video art that<br />

avoided the problematic male gaze by activating<br />

other senses in the viewer besides sight. She drew<br />

upon the theories of early 20 th -century art historian<br />

Alois Reigl, who posited that art advanced as it<br />

abandoned tactile physicality in favor of visual<br />

space. By reviving the haptic, Marks argued,<br />

feminists undermined the very logic of art history<br />

Fig. 14. W 629 worn by Stephen Goldman<br />

during filming by <strong>Stein</strong> at The Art Club in 2008<br />

that excluded women’s art. 17 In a presupposed<br />

hierarchy of senses, sight is less corporeal, more<br />

spiritual, and touch is more bound to the body.<br />

Reigl’s progression towards visuality traces a mindbody<br />

split; the aesthetic experience is increasingly<br />

cereberal as the eyes become the privileged<br />

means of apprehension. <strong>Stein</strong>’s use of the haptic<br />

as a mode of address is evident in the gloriously<br />

tactile surfaces of her Knights with their varied<br />

textures and materials. Engaging the viewer’s body<br />

imaginatively or literally, in the pieces to be worn,<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> incorporates alternatives to the primacy of<br />

visuality for understanding her sculptures and<br />

reactivates the viewer’s sense of embodiment.<br />

Art historian David Getsy, in his book on Victorian<br />

sculpture and aesthetic theory Body Doubles,<br />

15<br />

17<br />

19<br />

Figs. 15-21. Vestment 628. 2008. wood, metal. 52" × 18" × 6"<br />

plus 12" Lucite extensions resting on shoulders.<br />

Worn by <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, Carole Hyatt, Rob Okun,<br />

Elizabeth A. Sackler, Sallie Bingham and Merle Hoffman<br />

16<br />

18<br />

20<br />

Fig. 21<br />

9

10<br />

Fig. 22. Installation of variable dimensions.<br />

LEFT SCULPTURE: Knight of Courage 655. 2009. wood, metal, leather, paper, archival inks plus velcro straps. 45" × 16" × 9"<br />

RIGHT SCULPTURE: Silver Knight 666. 2009. wood, metal, leather, paper, archival inks plus velcro straps. 47" × 17" × 12"<br />

Figs. 23-24. Front & side views of Heroic Compassion 665. 2009. wood, metal, paper, and mixed media. 65" × 18" × 14"<br />

11

12<br />

identified the trace of sculptural experience left to<br />

the viewer’s memory as an imago, not an image.<br />

While a picture may be recalled instantly and<br />

fully as an image, a sculpture resists such mental<br />

summary, because encountering a sculpture is a<br />

haptic and temporal experience, not only visual. An<br />

imago, a term Getsy borrowed from psychology, is<br />

“a nexus in which memories, perceptions, bodily<br />

sensations, and tangential associations all engage<br />

and play.” 18 The power of <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights to fully<br />

engage the viewer’s body and through it the psyche<br />

in this way is clearly expressed in the videotapes of<br />

studio visitors wearing Vestment 628 [fig. 21]. For<br />

one woman, it triggered memories of her mother’s<br />

recent death in a profoundly experiential way: “This<br />

feels like turning into a corpse. … It’s as if part of<br />

my body is starting to calcify and become cold…<br />

so I don’t like this, can you get it off!” [fig. 20] But<br />

for a male visitor, the experience was enlighteningly<br />

androgynous: “There’s a celebratory feeling … and<br />

simultaneously there’s a feeling of hmm, this is a<br />

tough row to hoe, being female” [fig. 17].<br />

These two strong and distinct reactions to the<br />

same sculpture demonstrate that <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights<br />

do not prescribe a singular new ideal body type,<br />

and the artist thus avoids the philosophical misstep<br />

of replacing the terms of hegemony while its<br />

oppressive framework remains unaltered. Grosz<br />

cautions that a hegemonic norm or ideal based<br />

on a single body type must not be produced as a<br />

substitute for the existing corporeal ideal (which<br />

is masculine, white, bourgeois, young, and able);<br />

she prefers a field of types, each with its own<br />

specificity, non-homogenous, and multiple. 19<br />

Swapping matriarchy for patriarchy, as in some<br />

Goddess art from the 1970s and in Judy Chicago’s<br />

Dinner Party of 1979, has contributed to judgments<br />

of feminist art as simplistic and essentialist.<br />

Substituting powerful women for powerful men—<br />

Wonder Woman for Superman, say—tends to leave<br />

the hierarchical structure, and the constitutive<br />

power relations, in place. The Knights offer an ideal<br />

in that the artist intends them to uplift, to convey<br />

a positive message of peace and protection, but<br />

the principles take a variety of physical forms. In<br />

Heroic Line-Up 599 [fig. 25], for example, <strong>Stein</strong>’s<br />

Fig. 25. Heroic Line-Up 599. 2007. 3-D collage<br />

with archival inks on paper. 42" × 21" × 3".<br />

Also, limited edition archival print, 9" × 12"<br />

patron saints are on prominent display: Wonder<br />

Woman is arrayed across the sculpture’s chest,<br />

Princess Mononoke across the hips. Here are<br />

two versions of an empowered female figure, the<br />

gamine princess and the voluptuous super-hero,<br />

and the sculptural form they compose resembles<br />

neither body type but is instead androgynous,<br />

lacking secondary sexual characteristics. As<br />

noted previously, armor allows gender to be<br />

transcended, if temporarily. Silver Knight 666<br />

[figs. 23-24] is not obviously feminine, despite the<br />

rounded pectorals and images of Wonder Woman,<br />

nor definitively masculine, although the torso is<br />

broad and powerful. With these and other pieces,<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> seems to be working out the problem of<br />

embodied subjectivity and body ideals by insisting<br />

that morphology does not predict gender or its<br />

formative stereotypes.<br />

Despite the fluidity of gender that <strong>Stein</strong> represents<br />

as an alternative to the dominant ideal that, in<br />

Grosz’s words, “may be undermined through<br />

a defiant affirmation of a multiplicity, a field<br />

of differences, of other kinds of bodies and<br />

subjectivities,” 20 her Knights are also visibly<br />

inscribed by social forces. Indeed, the recognizable<br />

materials and the slightly legible texts<br />

remind the viewer that culture produces the<br />

body and redefining the body produces a shift in<br />

gendered subjectivity—which in turn may transform<br />

culture. Knights like Heroic Compassion 665<br />

make literal the way culture defines the body with<br />

its repetition of images of Wonder Woman and<br />

proliferation of texts, which the artist explains are<br />

not superficially applied to the sculptural form but<br />

materially constitute that form and are effectively<br />

identical with it. Image and text, the materials of<br />

cultural reproduction, produce the tangible body.<br />

<strong>Stein</strong>’s sculptures, in turn, work on the viewer’s<br />

body, through the imago they produce in memory<br />

and when they are worn in the staged encounter<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> calls Body-Swapping. The artist takes<br />

advantage of sculpture’s haptic qualities, its scale<br />

and tactility, to create surrogate bodies. Trying<br />

on new bodily constructions and constraints, the<br />

viewer may experience a shift in her embodied<br />

subjectivity. This is not to say that a different<br />

gender identification ensues, but rather that<br />

wearing <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights allows one to explore the<br />

contours of one’s gendered subjectivity. Suited<br />

up in <strong>Stein</strong>’s armor, the viewer experiences<br />

empathy with other corporeal types. From this new<br />

perspective, the viewer may imagine upheavals<br />

in existing knowledge structures, new power<br />

relationships among the genders. 0<br />

Fig. 26. The Power to Protect. Rosen Museum, 2006<br />

Fig. 27. Knight of New Thoughts 667. 2009.<br />

wood, metallic paper, leather, metal, fiber. 41" × 15" × 8"<br />

13

Fig. 28.<br />

Wonder Woman 632.<br />

2008. wood,<br />

acrylicized paper,<br />

archival inks.<br />

76" × 20" × 9"<br />

Figs. 29-30. LEFT: Dancer Kate Kennedy in a 2009 interactive performance<br />

at Le Petit Versailles. RIGHT: Shaman 635. 2008. Bronze. 49" × 16" × 8"<br />

Fig 31. River Knight 608. 2008. wood, metal, stone. 45" × 15" × 9"<br />

Fig. 32. Asian Armature 570.<br />

2006. wood. 71" × 21" × 5"<br />

Fig. 33. Wonder Woman 632. 2008. wood,<br />

acrylicized paper, archival inks. 76" × 20" × 9"<br />

Fig. 34. Knight of Tomorrow 630. 2007. bronze. 78" × 25" × 14" with detail.<br />

Sited outdoors in the Adelphi University 2008-10 Biennial<br />

Fig. 35. Knight of Healing 614. 2008. wood,metal,stone. 20" × 6" × 3"<br />

Fig. 36. Lotus Knight 603. 2007. wood,<br />

Fig. 37. Black Guard 633. 2008.<br />

Fig. 38. Heroes 592. 2007.<br />

wood, acrylicized paper,<br />

archival inks. 78" × 40" × 10"<br />

14 acrylicized paper, archival inks. 78" × 21" × 8"<br />

wood, bone, resin. 57" × 18" × 6"<br />

15

Fig. 39. Heroic Journey 602. 2007.<br />

3-D collage with archival inks. 42" × 14" × 4"<br />

16<br />

Fig. 40. Wall-F 642. 2008. paper,<br />

archival inks, wood, metal, foamcore. 58" × 19" × 5"<br />

Fig. 41. Shaman 575. 2006.<br />

wood, metal, stone.<br />

49" × 16" × 8"<br />

Fig. 42. E.R. 631. 2008.<br />

wood, metal, stone.<br />

73" × 24" × 13"<br />

Fig. 43. Strength 596. 2007.<br />

wood, acrylicized paper,<br />

archival inks. 23" × 5" × 3"<br />

Fig. 44. Security Knight 646.<br />

2009. wood, metal, leather, paper,<br />

archival inks. 57" × 18" × 6"<br />

Fig. 45. Country Knight 643. 2008. paper, archival inks,<br />

wood, metal, foamcore. 58" × 19" × 5"<br />

17

ABRIDGED BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES, JANUARY 2006 - SEPTEMBER 2009<br />

As Founder/President of the non-profit 501(c)(3) corporation, HAVE ART: WILL<br />

TRAVEL! Inc. (HAWT), <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s focus has been to encourage constructive<br />

and empowering male and female gender roles leading to Peace and Equality.<br />

As art editor of On The Issues Magazine, and in her other writings and<br />

lectures, <strong>Stein</strong> exposes and highlights sexism in the art world and beyond.<br />

For more complete information, see <strong>Stein</strong>’s archives housed at Smith College:<br />

www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/ssc/visit.html, or go to her website: www.<strong>Linda</strong><strong>Stein</strong>.com,<br />

or see her last catalog “The Power to Protect: Sculpture of <strong>Linda</strong><br />

<strong>Stein</strong>:” www.Amazon.com, or go to www.HaveArtWillTravel.org.<br />

Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2009 <strong>BODY</strong>-<strong>SWAPPING</strong> <strong>ARMOR</strong>, Flomenhaft<br />

Gallery, Chelsea, NY • LINDA STEIN SCULPTURE--STRONG SUIT: <strong>ARMOR</strong><br />

AS SECOND SKIN, National Association of Women Artists, Manhattan, NY •<br />

2007 ECcentric BODIES, Mason Gross School of the Arts Galleries, Rutgers<br />

University, New Brunswick, NJ • LINDA STEIN - THE POWER TO PROTECT:<br />

SCULPTURE OF LINDA STEIN, Nathan D. Rosen Museum, Boca Raton, FL<br />

• 2006 LINDA STEIN - KNIGHTS, SOFA, Chicago, IL, Longstreth Goldberg<br />

Art, Naples, FL • LINDA STEIN - WOMEN WARRIORS: THE YIN AND YANG,<br />

Flomenhaft Gallery, NY • LINDA STEIN - SCULPTURE OF THE HEROIC<br />

WOMAN, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, Jim Thorpe, PA • LINDA STEIN - WON-<br />

DER WOMAN REBORN, The Art Mission Gallery, Binghamton, NY • LINDA<br />

STEIN - HEROIC VISIONS, Longstreth Goldberg Art, Naples, FL<br />

Selected Group Exhibitions: 2009 VISIBILITIES, Birmingham-Southern<br />

College, AL • SALON 2009, Flomenhaft Gallery, NY • GALLERY ARTISTS,<br />

Longstreth Goldberg Art, Naples, FL • 2008 NOBIS SOLO, Tabla Rasa Gallery,<br />

Brooklyn, NY • GALLERY GANG 2ND BIENNIAL, Flomenhaft Gallery,<br />

Chelsea, NY • 2007 WOMEN’S WORK: HOMAGE TO FEMINIST ART, Tabla<br />

Rasa Gallery, Brooklyn, NY • WORKS ON PAPER - Flomenhaft Gallery, NY<br />

Selected Public Art: Le Petite Versailles, NY, Outdoor Exhibit and Body-<br />

Swapping Performance • Adelphi University, NY, 2008 Outdoor Biennial •<br />

International Design Center, Southwest FL • Portland State University, OR<br />

Education: Master’s Degree, Pratt Institute, NY • Bachelor’s Degree (Cum<br />

Laude), Queens College, NY • Pratt Graphics Center, NY • Art Students<br />

League, NY • School of Visual Arts, NY<br />

Press: Newspapers, Magazines & Journals: Journal of Lesbian Studies;<br />

“Ruptures of Vulnerability: <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knight Series,” by Ann V. Bible (forthcoming)<br />

• 2009 Summer, ARTnews, “Flomenhaft,” by Mona Molarsky, p. 129<br />

• Jun 24 - 30, The Villager, “Questioning gender, confronting fear: Tribeca<br />

sculptor conceives armor as empowering corrective,” by Elena Mancini, p.<br />

34 • May 14, The East Hampton Star, “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s Body Armor,” by Elise<br />

D’Haene, p.C2 • Apr 16, The East Hampton Star, “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s Strong Suit<br />

at The Art Club,” by Elise D’Haene, p.C2 • Spring, Voice Male, “How <strong>Linda</strong><br />

<strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights Safeguard Our Days,” by Jann Matlock and Joan Marter, pgs<br />

25-27 • Mar 15, NY Art Examiner, “Wonder Woman is Making a Movie in<br />

Manhattan,” by LA Slugocki • 2008 Sept 25; East Hampton Star; “<strong>Linda</strong><br />

<strong>Stein</strong>: The Art of Soft Power”; pg C2 • Fall; Bitch Magazine; “ Lady of The<br />

Knights: <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> and the Art of Soft Power”; by Amy Wolf, 3 black & white<br />

photos • May; On The Issues Magazine; “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> Knights;” by <strong>Linda</strong><br />

<strong>Stein</strong>, Art Editor, color photos • Mar; Curve Magazine; “Q+A <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>”; by<br />

Stephanie Schroeder, 1 color photo, p. 69 • Jan/Feb; Sculpture Magazine;<br />

“<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, Nathan D. Rosen Gallery, Boca Raton, FL;” by Skip Sheffield •<br />

Jan 12; Los Angeles Times; “Give Borat the boot”; by <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> • Jan 4;<br />

Los Angeles Times; “Dissecting the Tao of ‘Borat’ -- did we learn?;” By Hillel<br />

Felman • 2007 Fall, Feminist Studies, “Vestiges of New Battles: <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong><br />

Sculpture after 9/11,” by Jann Matlock • Jul 8, The NY Times, “Women’s<br />

Bodies as Art, Wrinkles and All,” by Benjamin Genocchio, 1 photo • Jun 14,<br />

BBC News, “Artist gets even after Borat hoax,” By Ian Youngs • wikipedia.<br />

org, “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>” • Mar, The Boca Raton Observer, “Sculptor <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s<br />

Warrior Women, The safety of objects,” by Robin Gelfand, p. 64-67 • Jan<br />

28, Sun-Sentinel “The Power to Protect” By Emma Trelles, Critics Choice,<br />

Arts Section • Jan 14, Boca Raton News “The Power to Protect: Sculpture<br />

of <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>” by Reshma Kirpalani, Society and the Arts p. 10 • Jan 8,<br />

Boca Raton News Online “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, ‘The Woman Who Stood Up To Borat,’<br />

Introduces ‘Warrior Woman’ at Rosen Gallery”, by Skip Sheffield • Jan 7,<br />

New Times Broward-Palm Beach “Make Benefit Glorious Boca”, by Lewis<br />

Goldberg • 2006 Feminists Who Changed America, “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>”, Barbara<br />

J. Love, p. 443 • Dec 20, artknowledgenews.com “‘The Power to Protect:<br />

Sculpture of <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’ at the Nathan D. Rosen Museum” • Nov 30, Rolling<br />

Stone, “The Man Behind The Moustache” by Neil Strauss, <strong>Stein</strong> photo<br />

& highlights p. 64 • Nov 27, Us Weekly, “Borat’s Angry Costars, Not very<br />

nice! The film’s unwitting dupes cry foul, Femme Fury,” by Mark Cina, p. 79<br />

• Nov 24, The Guardian, “The Borat Backlash,” By Patrick Barkham • Nov<br />

18<br />

17 - 23, Chelsea Now/Downtown Express, <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s defensive armor, by<br />

Ellison Walcott, p. 29 • Nov 16, Stern Magazine, “War doch nur Spaß”, by<br />

Michael Streck, p. 192 - 193 • Nov 15, Globus, Croatia, “AMERIKANCI NA<br />

UDARU LAŽNOG KAZAHSTANSKOG NOVINARA,” By Karmen Begovic, p.<br />

29 • Nov 10, Salon.com, “What’s real in ‘Borat’?,” By David Marese and Willa<br />

Paskin • Nov 9, London Times, “Borat’s ‘victims’ fail to see the funny side,”<br />

by Kevin Maher • Oct 26, Metro NY, “Borat interview shows artist’s flair,” by<br />

Heidi Patalano, p. 11 • Oct 24, Huffington Post, “Duped Borat Interviewee:<br />

‘He Owes Me One’...” • Oct 24, Slate.com, “Borat Tricked Me! Can’t I sue<br />

him or something?,” by Daniel Engber • Oct 23, BBC News, “How Borat<br />

hoaxed America,” by Ian Youngs • Oct 19, The East Hampton Star, “Sculptor<br />

Gets A Movie Role: Bamboozled by HBO’s appallingly gauche ‘Borat’,” by<br />

Sheridan Sansegundo • Oct 16, Newsweek, “Behind the Schemes,” by Devin<br />

Gordon, p.74-75. • Oct 13, Downtown Express, “How I was duped by Ali G.,”<br />

by <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, cover and p.29-30. • Oct 9, NY Post, “The Borat Trap’s Big<br />

Catch: How a fake Kazakh fooled a feminist,” by Andrea Peyser, p.11. • Jun<br />

21, Times News, Something for everyone at new Jim Thorpe exhibit, by Karen<br />

Cimms • May, ARTnews, Vol. 105, No. 5, <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, Longstreth Goldberg<br />

Art, Naples, FL, by Donald Miller, pgs. 171-172 • Summer, CALYX, A Journal<br />

of Art and Literature by Women, Vol. 23, No. 2, “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> Knights: A<br />

Sculpture Series after 9/11,” Essay by The Artsist, Front and Back Cover with<br />

color photos, p. 75-79, includes four photographs. • May-Jun, Harvard GLR/<br />

Worldwide Magazine, Vol. XIII, No. 3, “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>: Sculptor of the ‘Warrior<br />

Woman,’” <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> interviewed by Dr. Helen Hardacre, Text and 4 color<br />

photos on p. 30-31 • Apr 6, Press & Sun Bulletin, color photo on cover of<br />

“Good Times” entertainment section, “Artist Chat Tonight” text and photo<br />

on p. 3. • Spring, The Bridge, Vol. 1, Issue 4, “Sculpture evokes benevolent<br />

power,” text and photo on p. 34.<br />

Selected Essays for Exhibition Catalogs: 2009 MARGO HOBBS THOMP-<br />

SON - Body Swapping Empowerment and Empathy: <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s recent<br />

sculpture • 2006 JOAN MARTER - Regarding <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights and Glyphs •<br />

HELEN HARDACRE - Power and Protection: Japanese/American Crossroads<br />

and the Impact of 9/11 on the Sculpture of <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>.<br />

Book References: 2007 Baumgardner, Jennifer. Look Both Ways: Bisexual<br />

Politics. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007. • Napier, Susan J. From<br />

Impressionism to Anime: Japan as Fantasy and Fan Cult in the Mind of the<br />

West. NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, p. 211. • 2006 Love, Barbara J. Feminists<br />

Who Changed America, 1963-1975. Nancy F. Cott. Urbana Champaign:<br />

University of Illinois Press, 2006, p. 443<br />

Lectures/Presentations: 2009, Oct, “The Chance To Be Brave, The Courage<br />

To Dare”, Powerpoint presentation by <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, Elizabeth A. Sackler<br />

Wing of Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum. • Sept, Pollock-Krasner House,<br />

East Hampton, NY • May, “The Chance To Be Brave, The Courage To Dare”,<br />

Keynote address and Powerpoint presentation by <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> for the National<br />

Association of Women Artists, National Arts Club, Gramercy Park, NY •<br />

Apr, Masculinity/Femininity (Part II) dialogue between <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> & Michael<br />

Kimmel: , The Art Club, Tribeca, NY • Feb, <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> & Rob Okun: Masculinity/Femininity<br />

(Part I), The Art Club, Tribeca, NY • 2007 Aug, <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>:<br />

Art in the Age of Popular Culture, Harvard Project for Asian and International<br />

Relations, Convention Center, Beijing, China • Jul, The Power to Protect:<br />

Sculpture of <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, East Hampton Artist Alliance, Ashawagh Hall, East<br />

Hampton, NY • Jan, The Power to Protect: Sculpture of <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, Nathan<br />

D. Rosen Museum, Boca Raton, FL • Jun, <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knights of Protection<br />

after 9/11: A Comparison with Wonder Woman, Princess Mononoke and<br />

Kannon, Tuebingen Museum, Tuebingen, Germany • May, Power and Protection:<br />

Japanese and American Crossroads in the Sculpture of <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>,<br />

Miho Museum, Kyoto, Japan • Apr Wonder Woman Reborn: The Sculpture of<br />

<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>, Roberson Museum, Binghamton, NY<br />

TV and Movie Appearances: 2009 Aug 7, “Kulturplatz” with Eva Wannenmacher,<br />

Schweizer Fernsehen (Swiss TV) • 2007 Apr 13, E! Entertainment •<br />

Jan 24, WXEL, repeated on Feb 7th • 2006 Nov 15, “The Early Show,” CBS<br />

• Nov 13, Reuters • Nov 13, “The Situation Room with Paula Zahn,” CNN<br />

• Nov 12, “World News Sunday,” ABC • Nov 10, “Nightline,” ABC • Nov 3,<br />

<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong> appears in “Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit<br />

Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan,” 20th Century Fox • Oct 24-25, “Inside<br />

Edition,” Fox TV • Oct 9, CNBC, “The Big Idea” by Donny Deutch • Apr,<br />

“The New Yorkers,” Channel 26. • “<strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s Sculpture,” LTV Long Island<br />

Television, 50 minute interview by Haim Mizrahi<br />

Radio Interviews: 2007 Jun 18, “The Breakfast Show” Newstalk Radio,<br />

Ireland • Jun 15, “As it happens,” CBC Radio 1 • 2006 Dec 18, WBAI Cat<br />

Radio Café, NY Radio, by Janet Coleman • Nov 14, Detroit Radio • Nov 10,<br />

“The Morning Mess,” 93.1 WNOU-FM, Indianapolis, IN<br />

ENDNOTES<br />

1. Dr. Margo Hobbs Thompson is Assistant<br />

Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History<br />

at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania.<br />

She has published on gender and art in n.<br />

paradoxa, Genders, and GLQ.<br />

2. <strong>Stein</strong>’s PowerPoint lecture, “The Chance to Be<br />

Brave, The Courage to Dare” was delivered at the<br />

National Arts Club in Gramercy Park, New York<br />

City, May 20, 2009.<br />

3. Theodor Adorno was a German philosopher<br />

associated with the Frankfurt School of neo-<br />

Marxian social research. He made the statement in<br />

“An Essay on Cultural Criticism and Society” (1949;<br />

repr. in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber,<br />

Cambridge: MIT Press, 1967).<br />

4. Note that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in<br />

New York City is exhibiting “Art of the Samurai:<br />

Japanese Arms and Armor, 1156–1868,”<br />

from October 21, 2009–January 10, 2010<br />

5. Jann Matlock, “Vestiges of New Battles: <strong>Linda</strong><br />

<strong>Stein</strong>’s Sculpture after 9/11,” Feminist Studies 3, no.<br />

33 (Fall 2007), 569.<br />

6. During her lectures, <strong>Stein</strong> often asks young<br />

children “Is this sculpture a boy or a girl? What<br />

makes you think that?”<br />

7. Organized by curator Cornelia Butler,<br />

WACK! opened at the Los Angeles Museum<br />

of Contemporary Art in 2007 and traveled to<br />

the National Museum of Women in the Arts in<br />

Washington, DC, P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center<br />

in New York City, and the Vancouver Art Gallery.<br />

Art historian <strong>Linda</strong> Nochlin and Maura Reilly,<br />

Founding Curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler<br />

Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum,<br />

curated Global Feminisms, opening at the Brooklyn<br />

Museum in 2007.<br />

8. Kelli E. Stanley, “ ‘Suffering Sappho!’: Wonder<br />

Woman and the (Re)Invention of the Feminine<br />

Ideal,” Helios 32, no. 2 (2005), 145, 147.<br />

9. Stanley, 145.<br />

10. Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward<br />

a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana<br />

University Press, 1994), 19.<br />

11. Grosz, 20.<br />

12. Grosz, 20-1.<br />

13. Grosz, 21-2.<br />

14. <strong>Stein</strong>’s video Body-Swapping is<br />

accessible from YouTube: www.youtube.com/<br />

watch?v=shOqGEvwwHg<br />

15. Matlock as in first footnote; Ann V. Bible,<br />

“Ruptures of Vulnerability: <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong>’s Knight<br />

Series,” Journal of Lesbian Studies, forthcoming<br />

2010.<br />

16. Matlock, 586.<br />

17. Laura U. Marks, “Video Haptics and Erotics,”<br />

Screen 39, no. 4 (Winter 1998), 332, 335.<br />

18. David J. Getsy, Body Doubles: Sculpture in<br />

Britain, 1877-1905 (The Paul Mellon Centre for<br />

Studies in British Art. New Haven: Yale University<br />

Press, 2004), 37.<br />

19. Grosz, 22-3.<br />

20. Grosz, 19.<br />

CREDITS<br />

Fig. 46. Wonder Woman video in progress, Title Screen, 2009.<br />

Catalogue Production: Matt Lopez<br />

Catalogue Photography: D. James Dee, New York;<br />

<strong>Stein</strong> Studios, New York<br />

ISBN: 978-0-9790762-1-3<br />

Exhibition Coordinator: Eleanor Flomenhaft,<br />

Flomenhaft Gallery, New York<br />

© 2009 <strong>Linda</strong> <strong>Stein</strong><br />

All rights reserved<br />

Fig. 47. <strong>Stein</strong> at work. 2006<br />

BACK COVER: Fig. 48. Boxing Ring W 650. 2009. wood and metal. 49" × 18" × 6"<br />

547 W. 27th St., New York, NY 10001<br />

212.268.4952 flomanhaftgallery.com<br />

547 W. 27th St., New York, NY 10001<br />

212.268.4952 212.268.4952 flomanhaftgallery.com<br />

flomanhaftgallery.com<br />

19

5<br />

ISBN: 978-0-9790762-1-3