The phonology of fortis/lenis in Zapotec in - Natalie Operstein.

The phonology of fortis/lenis in Zapotec in - Natalie Operstein.

The phonology of fortis/lenis in Zapotec in - Natalie Operstein.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THE PHONOLOGY OF FORTIS/LENIS IN ZAPOTEC<br />

IN THE LIGHT OF LOANWORDS FROM SPANISH<br />

<strong>Natalie</strong> Operste<strong>in</strong><br />

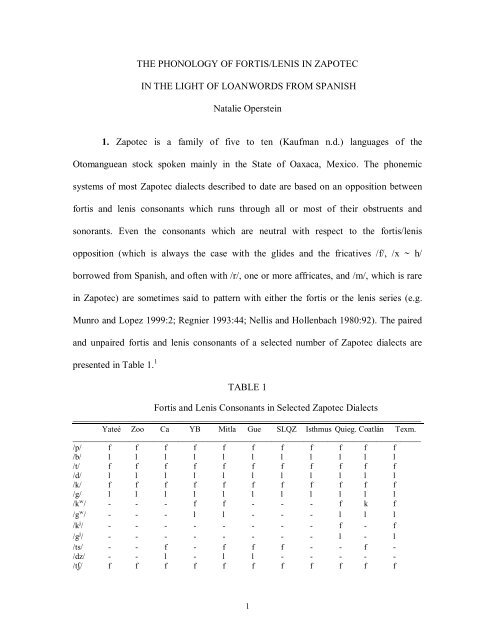

1. <strong>Zapotec</strong> is a family <strong>of</strong> five to ten (Kaufman n.d.) languages <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Otomanguean stock spoken ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> the State <strong>of</strong> Oaxaca, Mexico. <strong>The</strong> phonemic<br />

systems <strong>of</strong> most <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects described to date are based on an opposition between<br />

<strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> consonants which runs through all or most <strong>of</strong> their obstruents and<br />

sonorants. Even the consonants which are neutral with respect to the <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong><br />

opposition (which is always the case with the glides and the fricatives /f/, /x ~ h/<br />

borrowed from Spanish, and <strong>of</strong>ten with /r/, one or more affricates, and /m/, which is rare<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>) are sometimes said to pattern with either the <strong>fortis</strong> or the <strong>lenis</strong> series (e.g.<br />

Munro and Lopez 1999:2; Regnier 1993:44; Nellis and Hollenbach 1980:92). <strong>The</strong> paired<br />

and unpaired <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> consonants <strong>of</strong> a selected number <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects are<br />

presented <strong>in</strong> Table 1. 1<br />

TABLE 1<br />

Fortis and Lenis Consonants <strong>in</strong> Selected <strong>Zapotec</strong> Dialects<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Yateé Zoo Ca YB Mitla Gue SLQZ Isthmus Quieg. Coatlán Texm.<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

/p/ f f f f f f f f f f f<br />

/b/ l l l l l l l l l l l<br />

/t/ f f f f f f f f f f f<br />

/d/ l l l l l l l l l l l<br />

/k/ f f f f f f f f f f f<br />

/g/ l l l l l l l l l l l<br />

/k/ - - - f f - - - f k f<br />

/g/ - - - l l - - - l l l<br />

/k/ - - - - - - - - f - f<br />

/g/ - - - - - - - - l - l<br />

/ts/ - - f - f f f - - f -<br />

/dz/ - - l - l l - - - - -<br />

/t/ f f f f f f f f f f f<br />

1

d/ l l l l l l - l l l l<br />

/t/ - - - - - f - - - - -<br />

/d/ - - - - - - - - - - -<br />

/s/ f f f f f f f f f f f<br />

/z/ l l l l l l l l l l l<br />

// - f - f f f f f - f f<br />

// - l - l l l l l - l l<br />

// f f f f - f f - f - -<br />

// l l l l - l l - l - -<br />

/f/ - N/A f /loan loan N/A - f loan loan - N/A<br />

/x/ - N/A f /loan loan N/A - f - loan - N/A<br />

/h/ - - - - - - - N/A - - -<br />

// N/A - - - - - - - - - -<br />

/m:/ loan - f - f f f f - - -<br />

/m/ loan N/A - N/A l l l - l? N/A N/A<br />

/n:/ f f f f f f f f - - f<br />

/n/ l l l l l l l l l? N/A l<br />

/:/ - - - - - - - f - - -<br />

// - - - - - - - l - - -<br />

/l:/ f f f f f f f f - - f<br />

/l/ l l l l l l l l l? N/A l<br />

/r:/ - - f - f - f?/loan loan - - -<br />

/r/ loan N/A l N/A l l l? l r? loan N/A<br />

/j/ N/A N/A l N/A N/A N/A l N/A N/A N/A N/A<br />

/w/ N/A N/A l N/A N/A N/A l N/A N/A N/A N/A<br />

‘f’ and ‘l’ are <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong>, respectively, ‘N/A’ means that the phoneme is not said to participate <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> dichotomy, ‘-’ that the phoneme is not attested <strong>in</strong> this dialect, ‘loan’ that the phoneme is attested<br />

only <strong>in</strong> Spanish loanwords and has not been considered <strong>in</strong> the light <strong>of</strong> the <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> division. ‘Zoo’ is<br />

Zoogocho, ‘Ca’ is Cajonos, ‘YB’ is Yatzachi El Bajo, ‘SLQZ’ is San Lucas Quiav<strong>in</strong>í <strong>Zapotec</strong>, ‘Gue’ is<br />

Guelavía, ‘Quieg.’ is Quiegolani, ‘Texm.’ is San Lorenzo Texmelucan. For Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong>, I follow the<br />

phonemic analysis suggested <strong>in</strong> Marlett and Pickett (1987); <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ventory given <strong>in</strong> Pickett et al.<br />

(1998:121), /m/ is considered a <strong>lenis</strong> sonorant, there is a <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> pair r/rr, and // and /:/ are not cited<br />

as part <strong>of</strong> the phonemic system. Quioquitani <strong>Zapotec</strong>, <strong>in</strong> addition to the obstruents <strong>in</strong> this table, is also said<br />

to have the palatalized <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> pairs t/d, c/z, and s/z.<br />

Descriptively, the dist<strong>in</strong>ction between the two series <strong>of</strong> consonants is expressed<br />

differently <strong>in</strong> the sonorants than <strong>in</strong> the different groups <strong>of</strong> obstruents, and depends on the<br />

syllable position <strong>of</strong> the consonant. Correlates <strong>of</strong> <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> <strong>in</strong> different dialects spoken<br />

widely apart are <strong>of</strong> a recurr<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>d, and can be summarized <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong> a table: Table<br />

2 shows at a glance differences <strong>in</strong> the behavior <strong>of</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> consonants <strong>in</strong> different<br />

positions. Thus, <strong>fortis</strong> stops and affricates are always voiceless, aspirated word-f<strong>in</strong>ally,<br />

and are never lenited; their <strong>lenis</strong> counterparts show subphonemic variation <strong>in</strong> voic<strong>in</strong>g, no<br />

2

aspiration, and a tendency towards fricativization. Fortis affricates and fricatives are also<br />

said to have greater friction than their <strong>lenis</strong> counterparts. All <strong>fortis</strong> obstruents are said to<br />

be articulated more tensely than the <strong>lenis</strong> ones, and are lengthened after a stressed vowel.<br />

In sonorant consonants, the ma<strong>in</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g feature is the length: <strong>fortis</strong> sonorants are<br />

longer than the <strong>lenis</strong> ones. Fortis lateral is always voiced, while the <strong>lenis</strong> lateral can be<br />

devoiced and accompanied by friction. Both alveolar nasals are voiced, but only the <strong>lenis</strong><br />

one assimilates to the po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> articulation <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g consonant. Word-f<strong>in</strong>ally, the<br />

<strong>lenis</strong> alveolar nasal can be realized as velar or as the nasalization <strong>of</strong> the preced<strong>in</strong>g vowel.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> alveolar vibrant is a trill, and the <strong>lenis</strong> one is a tap. Until Avel<strong>in</strong>o (2001), all<br />

<strong>lenis</strong> consonants were claimed to lengthen the preced<strong>in</strong>g vowel; Avel<strong>in</strong>o has shown that,<br />

at least <strong>in</strong> the dialect he <strong>in</strong>vestigated, the lengthen<strong>in</strong>g effect is conf<strong>in</strong>ed to the obstruents.<br />

TABLE 2<br />

Correlates <strong>of</strong> Fortis/Lenis <strong>in</strong> Modern <strong>Zapotec</strong> Dialects<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Word- Intervocalically Word-<br />

<strong>in</strong>itially after stressed V f<strong>in</strong>ally<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

f stops/affricates - voice - voice - voice<br />

+ closure + closure + closure<br />

- aspiration - aspiration + aspiration<br />

- lengthen<strong>in</strong>g + lengthen<strong>in</strong>g - lengthen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

l stops/affricates +/- voice +/- voice +/- voice<br />

+/- closure +/- closure +/- closure<br />

- aspiration - aspiration - aspiration<br />

- length - length - length<br />

lengthens preced<strong>in</strong>g stressed V<br />

f fricatives - voice - voice - voice<br />

- lengthen<strong>in</strong>g + lengthen<strong>in</strong>g - lengthen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

l fricatives +/- voice +/- voice +/- voice<br />

- length - length - length<br />

lengthens preced<strong>in</strong>g stressed V<br />

f sonorants + length + length + length<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

3

<strong>The</strong> correlates <strong>of</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> summarized above and <strong>in</strong> Table 2 received first<br />

experimental confirmation <strong>in</strong> Jaeger’s (1983) study <strong>of</strong> the acoustic properties <strong>of</strong> Yateé<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong> consonants. This study suggests that the most important feature <strong>of</strong> the <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong><br />

contrast is likely to be acoustic duration (Jaeger 1983:187-88). A phonetic study <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> contrast <strong>in</strong> Yalálag <strong>Zapotec</strong> by Avel<strong>in</strong>o (2001) confirms and further elaborates<br />

this conclusion; <strong>in</strong> addition, Avel<strong>in</strong>o discards <strong>in</strong>tensity and articulatory strength as<br />

responsible for the <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> contrast, a suggestion repeatedly made <strong>in</strong> the literature on<br />

various <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects (2001:84-87).<br />

Swadesh (1947) related the <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> dichotomy <strong>in</strong> modern <strong>Zapotec</strong> to a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle/gem<strong>in</strong>ate dist<strong>in</strong>ction at the Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> level. In Swadesh’s view, supported and<br />

further developed <strong>in</strong> Suárez (1973), Kaufman (1983, 1994), and Benton (1988), <strong>lenis</strong><br />

obstruents and the sonorants /l/ and /n/ go back to s<strong>in</strong>gle consonants <strong>in</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong>,<br />

while their <strong>fortis</strong> counterparts orig<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> gem<strong>in</strong>ate consonants, some <strong>of</strong> which could<br />

have sprung from consonant clusters. As regards the present-day <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> pairs m:/m<br />

and r:/r, as well as the Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong> pair l:/l, only the <strong>lenis</strong> members <strong>of</strong> each pair go<br />

back to Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> sources, while their <strong>fortis</strong> counterparts represent later<br />

developments from other sources. Late creation <strong>of</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> counterparts to these sonorants<br />

is likely to be the result <strong>of</strong> paradigmatic pressure from other <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> pairs <strong>in</strong> the<br />

system. <strong>The</strong> immediate source <strong>of</strong> the newly developed <strong>fortis</strong> sonorants seems to have<br />

been compensatory lengthen<strong>in</strong>g, cf. the correlation between Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> /l:/<br />

and the length <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g vowel noted by Benton (1988:17), and that between <strong>fortis</strong><br />

/m:/ <strong>in</strong> SLQZ loanwords and the consonant clusters <strong>in</strong> their Spanish orig<strong>in</strong>als (e.g.<br />

4

zh:ommreel < sombrero ‘hat’, cha’mm < chamba ‘work’, tye’eemm < tiempo ‘time’, and<br />

xtro’oomm < trompo ‘top (toy)’).<br />

<strong>The</strong> tendency to restore the system to symmetry is especially apparent <strong>in</strong> those<br />

dialects <strong>in</strong> which the relationship between the <strong>fortis</strong> and the <strong>lenis</strong> members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

opposition has ceased to be that <strong>of</strong> length. <strong>The</strong> gap between the <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> sonorants<br />

is relatively small <strong>in</strong> Zaniza, Texmelucan, and Quioquitani <strong>Zapotec</strong> where, as the result<br />

<strong>of</strong> palatalization <strong>of</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> *nn and *ll, // and // now function as the <strong>fortis</strong><br />

counterparts <strong>of</strong> /n/ and /l/, respectively. In Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong>, where the historical result <strong>of</strong><br />

Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> *ll is /nd/, the etymological <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> pair nd/l is no longer perceived as<br />

such, which has probably contributed to the development <strong>of</strong> the non-etymological <strong>fortis</strong><br />

/l:/ mentioned above (Benton 1988:17). <strong>The</strong> tendency to restore the symmetry <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> opposition is also apparent <strong>in</strong> the treatment <strong>of</strong> the reflexes <strong>of</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong><br />

*ty (Suárez 1973, Kaufman 1983:111, Benton 1988:7-11). In those dialects or<br />

environments where the outcome <strong>of</strong> *ty is a <strong>lenis</strong> stop or affricate, it is symmetrically<br />

matched by the correspond<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fortis</strong> stop or affricate result<strong>in</strong>g from its gem<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

counterpart *tty. In the dialects or environments <strong>in</strong> which this proto-phoneme resulted <strong>in</strong><br />

a rhotic, it is no longer synchronically connectable to its etymological gem<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

counterpart, which has triggered the development <strong>of</strong> a <strong>fortis</strong> alveolar rhotic to fill the<br />

systemic gap (<strong>in</strong> Table 1, such dialects are Mitla, Cajonos, and possibly SLQ <strong>Zapotec</strong>).<br />

Various k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> evidence <strong>in</strong>dicate that <strong>in</strong> the sixteenth century the phonemic<br />

system <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> already operated on the basis <strong>of</strong> a <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> dichotomy. <strong>The</strong> most<br />

important early source <strong>of</strong> evidence is observations <strong>of</strong> Juan de Córdova, the first<br />

missionary grammarian <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>, on the pronunciation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> consonants and the<br />

5

ender<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Spanish words by the <strong>Zapotec</strong>s. Another, less direct but no less <strong>in</strong>formative<br />

source is the orthography employed by Córdova <strong>in</strong> his dictionary <strong>of</strong> the same dialect (cf.<br />

Manrique 1966-67; Smith 2000), as well as the orthography <strong>of</strong> other writ<strong>in</strong>gs dat<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

the same period (Broadwell 2000). Yet another source <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation on the phonemic<br />

system <strong>of</strong> sixteenth-century <strong>Zapotec</strong> is <strong>Zapotec</strong> render<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> numerous Spanish<br />

loanwords that entered its various dialects dur<strong>in</strong>g the course <strong>of</strong> that century.<br />

2. <strong>The</strong> phonemic system <strong>of</strong> sixteenth-century American Spanish has been studied<br />

<strong>in</strong> great detail (for an extensive bibliography on the subject see, e.g., Parodi 1995). For<br />

the phonemic system <strong>of</strong> contemporary <strong>Zapotec</strong> the only source currently available is an<br />

<strong>in</strong>-depth study by Smith (2000) <strong>of</strong> the <strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Valley dialect described by Juan<br />

de Córdova, based ma<strong>in</strong>ly on the orthography employed by Córdova <strong>in</strong> his dictionary <strong>of</strong><br />

this dialect (Córdova 1578b). <strong>The</strong> two phonemic systems are collated below (based on<br />

Parodi 1995:40 and Smith Stark 2000:54).<br />

16 th -c. Spanish 2 16 th -c. Valley <strong>Zapotec</strong><br />

p t t k p t t t k k<br />

b d g b d d d g<br />

z z <br />

f s h s h<br />

m n n <br />

r: mm nn r<br />

λ<br />

l ll<br />

w j w j<br />

6

Some <strong>of</strong> the most salient differences between the above systems <strong>in</strong>clude the fact that<br />

Spanish stops and fricatives constitute voiceless/voiced pairs while the correspond<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong> obstruents are divided <strong>in</strong>to <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong>, and the fact that Spanish has three<br />

series <strong>of</strong> sibilants and <strong>Zapotec</strong> only two. In addition, <strong>Zapotec</strong> has <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> versions<br />

<strong>of</strong> each sonorant except the /r/ which, at least accord<strong>in</strong>g to this <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong><br />

Córdova’s <strong>Zapotec</strong>, was absent from the system altogether: <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> what appears <strong>in</strong><br />

modern dialects as /r/ Córdova <strong>of</strong>ten writes a , which is <strong>in</strong>terpreted by Smith Stark as<br />

an alveolar stop, or the <strong>lenis</strong> member <strong>of</strong> the pair spelled above as t/d (cf. discussion <strong>of</strong> its<br />

possible surface phonetics <strong>in</strong> Smith 2000: 43-45). 3 F<strong>in</strong>ally, Spanish has a labiodental<br />

fricative which is alien to most <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects.<br />

3. <strong>The</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>der <strong>of</strong> this paper exam<strong>in</strong>es the treatment <strong>of</strong> Spanish consonants <strong>in</strong><br />

the earliest layer <strong>of</strong> Spanish borrow<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>. <strong>The</strong> earliest layer <strong>of</strong> loanwords is<br />

readily dist<strong>in</strong>guishable from the more recent borrow<strong>in</strong>gs primarily by the treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

Spanish sibilants and the //. For this study, a large number <strong>of</strong> early Spanish loanwordss<br />

<strong>in</strong> various dialects <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> has been assembled (the dialects exam<strong>in</strong>ed and the<br />

borrowed vocabulary are listed <strong>in</strong> the Appendix). Where there is sufficient data, a<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ction is made between the three consonantal positions important from the viewpo<strong>in</strong>t<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>phonology</strong>: word-<strong>in</strong>itial, <strong>in</strong>tervocalic, and word-f<strong>in</strong>al. <strong>Zapotec</strong> data are quoted<br />

<strong>in</strong> the orthography <strong>of</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al publications.<br />

Stops and /f/<br />

1(a) Spanish p-, b- (spelt , ) 4 > <strong>Zapotec</strong> b-:<br />

7

paño ‘cloth, sash, kerchief’ > Z bay(-ij), T bay, Zoo bay, Ca béy, A payu, YB bey,<br />

Co pai, I bayu’<br />

papaya > MZ baii, YB pey (<strong>in</strong> other dialects borrowed late)<br />

Pedro (name) > Z bed, Ca bε⊥d<br />

peso (a co<strong>in</strong>) > Z bèzh, T peζ&, MZ beex, AZ beψ)u, I beζ&u<br />

barato ‘cheap’ > Z bràd (<strong>in</strong> other dialects borrowed late)<br />

vaca ‘cow’ > Z bàg, MZ baag, SLQZ baag<br />

vigilia ‘vigil’ > Z bixily.<br />

Occasionally, the developments b- > m- or m- > b- are also attested:<br />

batea ‘tray’ > Z (yag-)mtey<br />

botón ‘button’ > Z mu(n)tuny<br />

muñeca ‘doll’ > I buñega’.<br />

1(b) Spanish -p-, -b- (spelt , ) > <strong>Zapotec</strong> -b-:<br />

Felipe (name) > Z lib, SLQZ Li’eb<br />

zapato ‘shoe’ > Z txubat<br />

compadre ‘godfather’ > SLQZ mbaaly, MZ mbaal, I mbale, A umpálí<br />

caballo ‘horse’ > Z kwey, T kΩáy, MZ cabaii, Zoo cabayw, YB cabey, Co wai,<br />

Q gay, SLQZ caba’i<br />

chivo ‘goat’ > Z txib, YB/Zoo σ&ib, SLQZ zhi’eb<br />

navaja ‘fold<strong>in</strong>g knife’ > Z nibàzh, SLQZ nabaazh, MZ nabaax<br />

novillo ‘young bull’ > Z nibily, SLQZ (gùu’ann) nabii.<br />

8

1(c) Spanish f > <strong>Zapotec</strong> p/b (if the names below were <strong>in</strong>deed borrowed early; cf. a<br />

different treatment <strong>of</strong> /f/ <strong>in</strong> the late loan Fransye’scw < Francisco <strong>in</strong> the same dialect):<br />

Florent<strong>in</strong>o > SLQZ Ploory<br />

Alfonsa > SLQZ Po’onnzy<br />

Felix > SLQZ Pu’isy<br />

Epifania > SLQZ Ba’nny.<br />

2(a) Spanish t-, d- > <strong>Zapotec</strong> t-, d-:<br />

taza ‘cup’ > Z tàz, T taz, A taza<br />

teja ‘ro<strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>g tile’ > I (yoo) deζ&a (yoo ‘house’), SLQZ deezh<br />

tijeras ‘scissors’ > Z tixer, MZ tixer, A tiyera, Q cer (< tser, cf. tmaz < Tomás)<br />

timón ‘beam’ > Z (yag-)tim, SLQZ dye’mm<br />

tomín (a co<strong>in</strong>) > A tummi<br />

testigo > Z testiw, YB testigw, SLQZ testi’u<br />

d<strong>in</strong>ero ‘money’ > T tíny<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>go ‘Sunday’ > Z timiw, MZ dum<strong>in</strong>ngw, Zoo/YB dmigw, SLQZ<br />

Domye’eenngw<br />

durazno ‘peach’ > YB tlas, A trasu, M duras, SLQZ dura’azn.<br />

2(b) Spanish -t-, -d- > <strong>Zapotec</strong> -t-, -d-:<br />

aceite ‘oil’ > Z ased<br />

Antonio (name) > Z Duny, SLQZ Nduuny (cf. also later To’nny)<br />

barato ‘cheap’ > Z bràd<br />

9

limeta ‘bottle’ > Z almet, Zoo lmet, YB lmet, Q lmet<br />

capitán ‘capta<strong>in</strong>’ > Z kaptá<br />

chocolate > Zoo s(i)cwlat, YB σ&cwlat, A choculati, Z txulad, MZ chiculajd,<br />

I dxuladi<br />

morado > Z m(b)ràd (YB morad, Zoo moradw, A moradu are late)<br />

testigo > Z testiw, YB testigw, SLQZ testi’u.<br />

2(c) <strong>The</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong> dj and d / __ i presents a special case: if borrowed early enough,<br />

they fall together with the reflexes <strong>of</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> *ty, cf.:<br />

Dios ‘God’ > Z dyuzh, T nygyooz, SLQZ Dyooz (Zoo Dios and similar forms are<br />

late borrow<strong>in</strong>gs)<br />

medio (a co<strong>in</strong>) > Zoo mechw, YB mech, Ca m:ej<br />

media ‘sock’ > T megy<br />

remedio > YB rmech, SLQZ (Nnambied Dela)rmuudy<br />

sandía > Z x<strong>in</strong>dyi.<br />

In at least one case, Spanish /r/ has a similar treatment:<br />

naranja ‘orange’ > nchaxhu (Diccionario 1995:33).<br />

Cf. the above treatments with the reflexes <strong>of</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> *ty <strong>in</strong> the same languages:<br />

*ke:tyu ‘hole’ (Kaufman 1994:21) > Z gedy, SLQZ guèèe’dy, Zoo yechw,<br />

YB yech<br />

*latyi (tawo) ‘heart’ (Kaufman 1994:20) > Z lady, T (rat) lagy(ã)<br />

*tyowa ‘mouth’ (Kaufman 1994:43) > Z rú’, T rù’, YB cho’a, SLQZ ru’uh,<br />

10

A rú’a.<br />

3(a) Spanish /k/- (spelt , )> <strong>Zapotec</strong> k- or g-:<br />

canoa ‘trough’ > Z kanu<br />

capitán ‘capta<strong>in</strong>’ > Z kaptá<br />

queso ‘cheese’ > Z kèzh, T kyez<br />

cochi ‘pig’ > Z kutx, YB/Zoo coσ&, Co kuucc, A cuttsi, SLQZ cu’uch, MZ cuch<br />

coles ‘cabbages’ > YB corix, A culiyi, Q kliz, SLQZ curehehizh, MZ curijxh 5<br />

cruz ‘cross’ > Z kruz, T kruuz, Zoo cruz, YB coroz, A curuuts, MZ crujz<br />

cuchillo ‘knife’ > MZ guchiil, Zoo cwsiyw, YB cwsiy, A gutsilu.<br />

3(b) Spanish g-, -/k/-, -g- > <strong>Zapotec</strong> g-, -g-:<br />

garbanzo ‘chickpea’ > Z garbaz, SLQZ garba’aannz<br />

garrote ‘stick, staff’ > SLQZ garrood, A yarróté (g- > y- is regular)<br />

vaca ‘cow’ > Z bàg, 6 MZ baag, SLQZ baag<br />

azúcar ‘sugar’ > Z asug<br />

amigo ‘friend’ > Z (a)miw, Zoo/YB migw, SLQZ amiiegw.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is at least one attested case <strong>of</strong> g- > /k/-, which may have to do with the g- be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a cluster:<br />

granada ‘pomegranate’ > Z karnad, SLQZ ca’rnaad.<br />

3(c) Word-f<strong>in</strong>ally, some dialects drop velar stops before rounded vowels:<br />

amigo ‘friend’ > Z (a)miw (but Zoo/YB migw, SLQZ amiiegw)<br />

11

trigo ‘wheat’ > Z triw, MZ triuu, SLQZ tri’u (but Zoo trigw)<br />

yegua ‘mare’ > Z yew, MZ yeuu (but YB yegw)<br />

nigua ‘maggot’ > Z níw, T niw, Co niu, Q niw, SLQZ niuw (but MZ nigw)<br />

banco ‘bank’, ‘bench’ > Z bãw (but SLQZ ba’aanngw, I bangu’)<br />

testigo > Z testiw, SLQZ testi’u (but YB testigw)<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>go > Z timiw (but MZ dum<strong>in</strong>ngw, YB/Zoo dmigw, A dom<strong>in</strong>gu, SLQZ<br />

Domye’eenngw).<br />

(In a later layer <strong>of</strong> loans <strong>in</strong> the same dialects, the velars are preserved <strong>in</strong> this position, cf.<br />

surco ‘furrow’ > Z xurk, T surk, MZ xurc, SLQZ zhu’arc.)<br />

To summarize: (1) voiceless and voiced labial stops are borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong>, both<br />

word-<strong>in</strong>itially and <strong>in</strong>tervocalically. One has to bear <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, however, that word-<strong>in</strong>itial<br />

<strong>fortis</strong> /p/ is extremely rare <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> (<strong>in</strong> some dialects it is not attested at all, cf. Avel<strong>in</strong>o<br />

2001:6; Nellis and Hollenbach 1980:93), so the <strong>lenis</strong> outcome is expected <strong>in</strong> that<br />

position; (2) Spanish alveolar stops are borrowed as either <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> both<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervocalically and word-<strong>in</strong>itially, while /d/ before /i/ is always treated as <strong>lenis</strong>; (3)<br />

Spanish <strong>in</strong>itial /k/- can be borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong>, while <strong>in</strong>tervocalic -/k/-, along with<br />

<strong>in</strong>itial and <strong>in</strong>tervocalic /g/, tends to be borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong>. Thus, only labial Spanish stops<br />

are always borrowed <strong>in</strong>to <strong>Zapotec</strong> as <strong>lenis</strong>. <strong>The</strong> alveolar and velar stops show a great deal<br />

<strong>of</strong> vacillation <strong>in</strong> this respect, but at any rate the pattern <strong>of</strong> their borrow<strong>in</strong>g does not<br />

correlate with their voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Spanish. While the alveolar stops are borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> or<br />

<strong>lenis</strong> <strong>in</strong> approximately equal proportion, most <strong>in</strong>itial /k/’s are borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> and most<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervocalic /k/’s as <strong>lenis</strong>. This perhaps has to do with the frequency <strong>of</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> phonemes <strong>in</strong> native <strong>Zapotec</strong> words, or with different correlates <strong>of</strong> the<br />

12

<strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ction <strong>in</strong> the three series <strong>of</strong> early <strong>Zapotec</strong> stops. Thus, a careful study <strong>of</strong><br />

the treatment <strong>of</strong> stops <strong>in</strong> early Spanish loans <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> only partially confirms<br />

Kaufman’s (n.d.:18) observation that they, along with other obstruents, were borrowed as<br />

<strong>lenis</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> affricate<br />

In most dialects Spanish /t/ was borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong>, both word-<strong>in</strong>itially and<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervocalically:<br />

chocolate > Z txulad, Zoo s(i)cwlat, YB scwlat, Ca cíkwlát, MZ chiculajd<br />

(but I dxuladi)<br />

chivo ‘goat’ > Z txib, T ciib, Zoo/YB sib, Ca cib (but SLQZ zhi’eb)<br />

coche ‘pig’ > Z kutx, MZ cuch, Zoo/YB cos, Co kuucc, A cuttsi, SLQZ cu’uch<br />

cuchara ‘spoon’ > Zoo cwsar, YB c(w/o)sar (but SLQZ wzhyaar, I (g)udxara)<br />

cuchillo ‘knife’ > MZ guchiil, Zoo cwsiyw, YB cwsiy, Z gutsilu, SLQZ bchiilly<br />

(but I (g)udxíu)<br />

macho ‘mule’ > Z matx, T mac, Zoo masw, YB mas (but MZ madz)<br />

machete > Zoo maset, YB mset, Co macctt (but MZ madxed, SLQZ<br />

mazhye’edy, Q mzæd)<br />

mecha ‘wick’ > T mec, Ca m:ec. 7<br />

Reflexes <strong>of</strong> this affricate <strong>in</strong> early loanwords co<strong>in</strong>cide with those <strong>of</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong><br />

gem<strong>in</strong>ate *cc <strong>in</strong> native morphemes, cf.:<br />

13

*ccho-n(n)a ‘three’ (Benton 1988 #122 ) > Z txun, T con, Zoo sone, YB son, A<br />

tsunná, Ca cón:é, MZ chon<br />

Sibilants<br />

*kiccha ‘hair’ (Benton 1988 #55)/*kittza(7) (Kaufman 1994:20) > Z gitx, T gyìc,<br />

Zoo yisa’, YB yis’, A íttsa’ (íqquia), SLQZ gyihch, Co kìcc.<br />

1(a) Spanish /s/ (spelt , ) and /z/ (spelt ) 8 > <strong>Zapotec</strong> /z/ and /s/:<br />

arroz ‘rice’ > Z arùz, YB roz (Zoo ros, SLQZ rro’s are late)<br />

azúcar ‘sugar’ > Z asug (MZ su’cr, Zoo/YB sucr, SLQZ sua’rc may be late)<br />

ciudad ‘city’ > Z siwda, Zoo ciuda, YB syoda, SLWZ syudaa<br />

coc<strong>in</strong>ero ‘cook’ > Z kusnely<br />

cruz ‘cross’ > Z cruz, Zoo cruz, YB coroz, MZ crujz (SLQZ cru’uhsy may be<br />

late)<br />

durazno ‘peach’ > YB tlas, A trasu, SLQZ dura’azn, MZ duras (all may be late)<br />

garbanzo ‘chickpea’ > Z garbaz, SLQZ garba’aannz, MZ garbans (late)<br />

mazo ‘mallet’ > Z mez, T mãz, Zoo/YB maz, SLQZ maaz, MZ mas (late)<br />

mostaza ‘mustard’ > MZ (yag) muxtas (yag ‘tree’)<br />

mozo ‘servant’ > Z mùz (MZ/Zoo/YB mos is late).<br />

It is likely that part or all <strong>of</strong> the loanwords <strong>in</strong> which Spanish /s/ <strong>of</strong> /z/ > <strong>Zapotec</strong> /s/ were<br />

borrowed later than those <strong>in</strong> which Spanish /s/ or /z/ > <strong>Zapotec</strong> /z/.<br />

1(b) <strong>The</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong> two loanwords can be taken as an <strong>in</strong>dication <strong>of</strong> its affricated<br />

pronunciation <strong>in</strong> Spanish. Spanish zapato ‘shoe’ was borrowed <strong>in</strong> Zaniza <strong>Zapotec</strong> as<br />

txubat, and Spanish cruz ‘cross’ was borrowed <strong>in</strong> Atepec <strong>Zapotec</strong> as curuuts. Zaniza tx<br />

14

and Atepec ts normally render Spanish ch (cf. chivo ‘goat’ > Z txib and cuchillo ‘knife’ ><br />

A gutsilu). <strong>The</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong> these loans is therefore consistent with its affricated<br />

pronunciation (/ts/) <strong>in</strong> Spanish, and may be taken as evidence for a late survival <strong>of</strong> this<br />

affricate.<br />

2. Spanish // (spelt , ) and /⏐ / (spelt ) > <strong>Zapotec</strong> // or //:<br />

sacristán > Z xundista, A yueda(yoto’) [yoto’ ‘temple, church’], SLQZ<br />

sacax:taany<br />

san, santo ‘sa<strong>in</strong>t’ > I (beu) zandu’; za(bizende) ‘San Vicente’, SLQZ Xann(daan)<br />

‘Santa Ana’; Xmo’oony ‘Santa Mónica’<br />

semana > Z ximan, YB sman, Zoo xman, A yumanu, Ca zm:an, SLQZ/MZ<br />

xmaan<br />

silla ‘chair’, ‘saddle’ > Z xily, T sily, MZ (yag)xhil, SLQZ zhi’iilly, A xila’<br />

sombrero > MZ xhumbreel, SLQZ zh:ommreel<br />

escuela > Z xikwal<br />

camisa > Z mìzh, MZ (re-)gamizh, A miya, I gamiza<br />

manso > Z màzh, T maz, YB max, MZ madx<br />

misa ‘mass’ > Z mìzh, T míz, I míza’ , MZ mix, A miya (YB/Zoo mis, SLQZ<br />

mye’es are late)<br />

peso > Z bezh, T pez, MZ beex, A beyu, I bezu<br />

Dios > Z dyuzh, T nygyooz, A (Tata) Diuy(a), I dyuzi, Q dyuz (< adiós)<br />

Tomás > Z màzh, SLQZ Ma’azhy, Q tmaz<br />

15

Luis > Z wizh, T wiiz.<br />

In the dialects that currently dist<strong>in</strong>guish (and probably did so <strong>in</strong> the sixteenth century)<br />

between alveopalatal and retr<strong>of</strong>lex sibilants, Spanish // and // were borrowed, with<br />

very few exceptions, as alveopalatal.<br />

3. Spanish // (spelt ) and // (spelt and ) > <strong>Zapotec</strong> // or //:<br />

jabón ‘soap’ > I zabú<br />

jarro ‘pitcher’ > A yaru(iyya) [iyya ‘flower’]<br />

jer<strong>in</strong>ga ‘syr<strong>in</strong>ge’ > I zir<strong>in</strong>ga<br />

jícara ‘calabash cup’ > Z xìg, I ziga, SLQZ zh:i’ahg, MZ xijg, YB xigu’<br />

Juana (name) > Ca zwán, SLQZ Zh:ùaan<br />

gigante > Z xigan<br />

aguja ‘needle’ > A gúψ)á, MZ guux, SLQZ (guìi’ch)gwu’ùa’zh:<br />

ajo ‘garlic’ > Z àzh, T az, Zoo/YB (cuan)ax, A gayu, SLQZ (xti)aazh, MZ aax<br />

arveja ‘pea’ > A (daa)ribeyi (daa ‘beans’)<br />

clavija ‘peg’ > Z (yag-)kabizh (yag ‘wood’), SLQZ garbiizh<br />

mixe ‘Mixe’ > MZ miix, YB/Zoo mix, SLQZ Miìi’zh<br />

naranja > T láz, A maraya, SLQZ nraazh, MZ naraax<br />

navaja > Z nibazh, SLQZ nabaazh, MZ nabaax<br />

tijeras ‘scissors’ > Z tixer, MZ tixer, Q cer (< tser), A tiyera, SLQZ (gyìe’b)<br />

zhiier.<br />

16

In dialects that currently dist<strong>in</strong>guish between alveopalatal and retr<strong>of</strong>lex sibilants, //<br />

and // were borrowed as alveopalatal.<br />

To summarize: (1) the affricate ch is mostly borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong>; (2) /s/ (and /z/)<br />

are mostly borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong>, but <strong>in</strong> Zaniza zapato and Atepec cruz they are rendered like<br />

Spanish ch and may reflect an affricated pronunciation <strong>of</strong> Spanish ; (3) Spanish<br />

//, //, // and // are borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> alveopalatal fricatives (// and //) word-<br />

<strong>in</strong>itially, and, with one exception, as <strong>lenis</strong> (//) <strong>in</strong>tervocalically. Thus, the pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

render<strong>in</strong>g obstruents <strong>in</strong> Spanish loans that emerges is a complex one. As can be seen<br />

from Table 3, the voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Spanish obstruents does not affect the borrow<strong>in</strong>g pattern,<br />

which <strong>in</strong>stead seems to depend on other factors.<br />

TABLE 3<br />

Render<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Spanish Obstruents <strong>in</strong> Early <strong>Zapotec</strong><br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Word-<strong>in</strong>itially Word-medially Word-f<strong>in</strong>ally<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

p, b (, ) l l not attested<br />

t, d f/l f/l not attested<br />

d+i l l not attested<br />

/k/ f/l l not attested<br />

g l l not attested<br />

ch f f not attested<br />

/s/, /z/ l l l<br />

//, //, //, // f/l l l<br />

4. <strong>The</strong> <strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Córdova’s <strong>Zapotec</strong> based on a study <strong>of</strong> his orthography<br />

(Smith Stark 2000) can be <strong>of</strong> some assistance <strong>in</strong> elucidat<strong>in</strong>g the above borrow<strong>in</strong>g pattern.<br />

<strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g traits <strong>of</strong> Córdova’s orthography appear to be relevant: (1) there seem to be<br />

no examples <strong>of</strong> word-<strong>in</strong>itial <strong>fortis</strong> /p/; (2) only the letters used for render<strong>in</strong>g voiceless<br />

obstruents <strong>in</strong> Spanish are used <strong>in</strong> render<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fortis</strong> obstruents <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>; (3) the letters<br />

17

used for voiced obstruents <strong>in</strong> Spanish can be used <strong>in</strong> render<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>lenis</strong> segments<br />

/b/, /g/, /z/, and /Ζ/; (4) both <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> dental stops are represented by the letter ;<br />

(5) <strong>fortis</strong> obstruents <strong>in</strong> Córdova’s <strong>Zapotec</strong> were apparently lengthened <strong>in</strong> posttonic<br />

syllables s<strong>in</strong>ce the <strong>in</strong>frequent examples <strong>of</strong> double spell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> consonants are conf<strong>in</strong>ed to<br />

this position; (6) <strong>Zapotec</strong> /s/ and /z/ are reasonably well differentiated graphically, but<br />

// and // are not (Smith 2000:32-33, 35-46). Additional <strong>in</strong>formation on the <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong><br />

<strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Córdova’s <strong>Zapotec</strong> may be found <strong>in</strong> his remarks <strong>in</strong> the Arte. Here, Córdova<br />

enumerates such mistakes made, he says, mostly by Spaniards <strong>in</strong> their <strong>Zapotec</strong>, as<br />

pronounc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tervocalic /b/ for /p/, /g/ for /k/ and vice versa, /z/ for /s/, <strong>in</strong>itial /d/ for<br />

Spanish /t/ (‘Doledo’ for ‘Toledo’), and (alveopalatal sibilant) for (retr<strong>of</strong>lex<br />

sibilant) (1578a:73). While it is likely that some <strong>of</strong> these observations reflect more on<br />

Córdova’s Spanish than on his <strong>Zapotec</strong>, they seem to expla<strong>in</strong> (1) the absence <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial<br />

<strong>fortis</strong> /p/ <strong>in</strong> render<strong>in</strong>g Spanish loans (expla<strong>in</strong>able by the absence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial /p/ <strong>in</strong> native<br />

words), (2) the little role played by the voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Spanish obstruents <strong>in</strong> the overall<br />

borrow<strong>in</strong>g pattern and especially <strong>in</strong> that <strong>of</strong> the dental stops, and (3) the absence <strong>of</strong><br />

render<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervocalic Spanish /p/ and /k/ as <strong>fortis</strong> (expla<strong>in</strong>able by the lengthen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

the native <strong>fortis</strong> obstruents <strong>in</strong> this position). In addition, Córdova’s observations on the<br />

pronunciation mistakes that <strong>in</strong>volve voiced and voiceless alveolar sibilants and only the<br />

voiceless alveopalatal sibilant probably po<strong>in</strong>t to the voicelessness <strong>of</strong> // <strong>in</strong> his Spanish,<br />

which <strong>in</strong> turn expla<strong>in</strong>s the under-differentiation <strong>of</strong> // and // <strong>in</strong> his <strong>Zapotec</strong> orthography.<br />

5. Nasals<br />

1(a) Spanish m > m <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

18

macho ‘mule’ > Z matx, T mac, MZ madz, Zoo masw, YB mas<br />

mazo ‘mallet’ > Z mez, Tmãz, Zoo/YB maz, SLQZ maaz, MZ mas<br />

mula ‘female mule’ > Z/T muly, MZ mul, SLQZ muuall<br />

almohada ‘pillow’ > Z almàd, YB lmad, SLQZ almwaad<br />

amigo ‘friend’ > Z (a)miw, YB/Zoo migw, SLQZ amiiegw<br />

limeta ‘bottle’ > Z almet, Zoo lmet, YB lmet<br />

compadre ‘godfather’ > A umpali, SLQZ mbaaly, MZ mbaal, I mbale<br />

comadre ‘godmother’ > I male, Ca m:ál<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>go > Z timiw, MZ dum<strong>in</strong>ngw, Zoo/YB dmigw, Z dom<strong>in</strong>gu, SLQZ<br />

Domye’eenngw<br />

semana ‘week’ > Z ximan, YB σ&man, Zoo xman, A yumanu, SLQZ/MZ xmaan.<br />

1(b) Cases where Spanish /m/ was borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> have to do with the loss <strong>of</strong> a<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g consonant and subsequent compensatory lengthen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the nasal:<br />

sombrero ‘hat’ > SLQZ zh:ommreel<br />

timón ‘beam’ > SLQZ dye’mm<br />

tiempo ‘time’ > SLQZ tye’eemm<br />

trompo ‘top’ (toy) > SLQZ xtro’oomm<br />

tomín (co<strong>in</strong>) > A tummi.<br />

1(c) Some /m/’s <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> loans resulted from other consonants:<br />

batea ‘tray’ > Z (yag-)mtey<br />

botón ‘button’ > Z mu(n)tuny<br />

19

naranja ‘orange’ > A maraya, Ca m:raz, mbrhaxh (Diccionario 1995:33).<br />

2(a) Spanish n- > <strong>lenis</strong> n- <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

naranja ‘orange’ > SLQZ nraazh, MZ naraax<br />

navaja ‘fold<strong>in</strong>g knife’ > Z nibazh, SLQZ nabaazh, MZ nabaax<br />

nigua ‘maggot’ > Z niw, Co niu, SLQZ niuw, MZ nigw, Q niw<br />

novillo ‘young bull’ > Z nibily, SLQZ (gùu’ann) nabii.<br />

2(b) Spanish -n- > <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> -n- <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

d<strong>in</strong>ero ‘money’ > T tíny<br />

m<strong>in</strong>a ‘m<strong>in</strong>e’ > T m<strong>in</strong>y<br />

panela ‘sugar loaf’ > Z p<strong>in</strong>yal<br />

semana ‘week’ > Z ximan, YB sman, Zoo xman, A yumanu, SLQZ/MZ xmaan.<br />

Spanish -n- tends to be lost before fricatives, but is preserved before stops:<br />

garbanzo ‘chickpea’ > Z garbaz, SLQZ garba’aannz<br />

manso ‘tame’ > Z màzh, T maz, YB max, MZ madx<br />

naranja ‘orange’ > A maraya, Ca m:raz, T láz, SLQZ nraazh, MZ naraax<br />

sandía ‘watermelon’ > Z x<strong>in</strong>dyi, SLQZ xanndiia, I zandie’<br />

culantro ‘cilantro’ > Z kulyandr, A culandru, SLQZ cura’aann<br />

banco ‘bank’, ‘bench’ > SLQZ ba’aanngw, Z bãw, Zoo/YB bancw, I bangu’<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>go ‘Sunday’ > MZ dum<strong>in</strong>ngw, SLQZ Domye’eenngw, A dom<strong>in</strong>gu.<br />

20

2(c) Word-f<strong>in</strong>al Spanish -n can be rendered by a <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> nasal, or be lost,<br />

depend<strong>in</strong>g on the dialect:<br />

sacristán > Z xundista, A yueda(yoto’), SLQZ sacax:taany<br />

timón ‘beam’ > Z (yag-)tim, SLQZ dye’mm (-mm < *-mn; note also the stress<br />

shift)<br />

tomín (a co<strong>in</strong>) > A tummi<br />

botón ‘button’ > Z mu(n)tuny, SLQZ btoony.<br />

3(a) Spanish ñ > <strong>lenis</strong> n <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

albañil ‘mason’ > Z arbanyil, YB/Zoo albanil<br />

escaño ‘bench with a back’ > YB/Zoo xcan, MZ xcaan.<br />

3(b) <strong>The</strong>re is also one example <strong>of</strong> an early loan <strong>in</strong> which Spanish ñ > <strong>Zapotec</strong> y:<br />

paño ‘cloth’ > Z bay(-ij), T bay, I bayu’, Co pai, A payu, YB bey, Zoo bay.<br />

<strong>The</strong> uniform outcome <strong>of</strong> ñ as a glide, despite the fact that Córdova’s and doubtless other<br />

dialects had or could have had a palatal nasal match<strong>in</strong>g the Spanish ñ seems to argue for a<br />

borrow<strong>in</strong>g through the medium <strong>of</strong> Nahuatl, where y is one <strong>of</strong> the possible outcomes <strong>of</strong><br />

early Spanish ñ, and paño is reflected as payo (cf. González Casanova 1977:131, 146).<br />

Liquids<br />

1(a) Spanish l- > <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> l- <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

lazo > T laz<br />

limeta ‘bottle’ > Z almet, Zoo lmet, YB lmet, Q lmet<br />

lunes ‘Monday’ > Z lunex, MZ lun, Zoo lun, YB (zha) lon, A luni, SLQZ Luuny<br />

21

Lucas (name) > Z lyuj, T luk, SLQZ Lu’c.<br />

1(b) Spanish -l- > <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> -l- <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

alguacilillo (dim. <strong>of</strong> alguacil ‘constable’) > SLQZ lasliiery<br />

culantro ‘cilantro’ > Z kulyandr (YB culantr, A culandru)<br />

chocolate > Z txulad, Zoo s (i)cwlat, YB σ&cwlat, MZ chiculajd<br />

escuela ‘school’ > Z xikwal<br />

mezcal ‘agave liquor’ > Z mixcaly (Zoo mezcal, YB mescal, SLQZ mescaaly)<br />

mole ‘stew with chili sauce’ > SLQZ mo’lly, MZ moll<br />

mula ‘female mule’ > Z/T muly, MZ mul, SLQZ muuall<br />

panela ‘sugar loaf’ > Z p<strong>in</strong>yal (YB/Zoo panel, MZ paneel)<br />

real (a co<strong>in</strong>) > YB ryel ~ riel, A rriali, SLQZ rryeelly, MZ räjl<br />

vigilia ‘vigil’ > Z bixily<br />

Manuel (name) > Z wely, SLQZ Ne’ll<br />

Pablo (name) > T baly<br />

Samuel (name) > Z wely, T mel.<br />

1(c) <strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> /l/ can result from other Spanish consonants:<br />

from /r/:<br />

coc<strong>in</strong>ero ‘cook’ > Z kusnely<br />

compadre ‘godfather’ > A umpali, SLQZ mbaaly, MZ mbaal, I mbale<br />

comadre ‘godmother’ > I male<br />

durazno ‘peach’ > YB tlas<br />

22

from /d/:<br />

naranja ‘orange’ > T láz<br />

sombrero ‘hat’ > A umbrelu, MZ xhumbreel, SLQZ zh:ommreel;<br />

medio (a co<strong>in</strong>) > SLQZ mùuully, MZ meel (and probably A belliu).<br />

2(a) Spanish ll [×] > <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> l <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>:<br />

llave ‘key’ > SLQZ lye’i, MZ liäii<br />

cuchillo ‘knife’ > MZ guchiil, A gutsilu, SLQZ bchiilly (but YB cwshiy,<br />

Zoo cwshiyw, I gudxíu)<br />

Castilla ‘Castile’ > ZooZ (dizha’)xtil,YB (dizhe’e)xtil, A (la’a)xtila, MZ<br />

(didx)xtiil ‘Spanish (language)’ 9<br />

manzanilla ‘camomile’ > MZ maNsanil (N = <strong>fortis</strong> /n/)<br />

mol<strong>in</strong>illo ‘hand mill’ > SLQZ mo/urniilly, MZ morniil<br />

novillo ‘young bull’ > Z nibily<br />

silla ‘chair’, ‘saddle’ > Z xily, T σ&ily, MZ (yag)xhil, SLQZ zhi’iilly, A xila’.<br />

2(b) A couple <strong>of</strong> loans provide evidence <strong>of</strong> early yeísmo (i.e. the pronunciation <strong>of</strong><br />

Spanish ll as [y]):<br />

caballo ‘horse’ > Z kwey, at káy, Co wai, YB cabey, MZ cabaii, Zoo cabayw,<br />

SLQZ caba’i, Q gay<br />

pollo ‘chicken’ > Co poi, I buyu’.<br />

3(a) Spanish r- (a trill) > <strong>Zapotec</strong> rr-/r- (one example):<br />

23

eal (a co<strong>in</strong>) > YB ryel ~ riel, A rriali, SLQZ rryeelly, MZ räjl.<br />

3(b) Spanish -rr- and -r- > <strong>Zapotec</strong> (<strong>lenis</strong>) r:<br />

arroz ‘rice’ > Z arùz, YB roz<br />

barato ‘cheap’ > Z bràd (also MZ bará’t, Zoo baratw, YB barat, SLQZ baraa’t)<br />

morado ‘purple’ > Z m(b)ràd (also YB morad, Zoo moradw, A moradu)<br />

naranja ‘orange’ > A maraψ)a, SLQZ nraazh, MZ naraax<br />

Andrés (name) > MZ ndré(h)zh.<br />

3(c) <strong>Zapotec</strong> /r/ can also result from Spanish /l/ and //:<br />

alguacilillo (dim. <strong>of</strong> alguacil ‘constable’) > SLQZ lasliiery<br />

albañil ‘mason’ > Z arbanyil<br />

alcalde ‘mayor’ > Zoo rcal, YB rcal, SLQZ rca’alldy<br />

clavija ‘beam’ > SLQZ garbiizh, Z (yag-)kabizh<br />

coles ‘cabbages’ > YB corix, Ca kórìσ&, SLQZ curehehizh, MZ curijxh<br />

culantro ‘cilantro’ > SLQZ cura’aann<br />

mol<strong>in</strong>illo ‘hand mill’ > SLQZ mo/urniilly, MZ morniil.<br />

In some cases (as <strong>in</strong> albañil, alcalde, mol<strong>in</strong>illo) this development can be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by<br />

dissimilation.<br />

In one case, <strong>Zapotec</strong> -r- has probably resulted from Zpanish -d-:<br />

maravedí (an old co<strong>in</strong>) > Z mrí ‘money’, T mbrii ‘six centavos’. 10<br />

To summarize the situation with the borrow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> sonorants: (1) Spanish /m/ is<br />

borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> only when the loss <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g consonant causes its compensatory<br />

24

lengthen<strong>in</strong>g; (2) <strong>in</strong>itial /n/ is borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong>, while <strong>in</strong>tervocalic and word-f<strong>in</strong>al /n/ may<br />

be borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong> or <strong>fortis</strong>. This situation may have someth<strong>in</strong>g to do with the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> the <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> /n/ <strong>in</strong> native <strong>Zapotec</strong> words: thus, Benton (1988:15-16)<br />

does not reconstruct word-<strong>in</strong>itial *nn- or <strong>in</strong>tervocalic *-n- <strong>in</strong> his version <strong>of</strong> Proto-<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong>; (3) Spanish ñ is borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong> /n/, with the exception <strong>of</strong> the word paño,<br />

likely to have been borrowed through Nahuatl, where Spanish ñ > <strong>Zapotec</strong> y; (4) Spanish<br />

/l/ and // are borrowed as either <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> /l/ and occasionally as an /r/; (5) at least<br />

two loanwords provide evidence for early yeísmo; (6) Spanish trilled /r/ is occasionally<br />

borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong> <strong>in</strong> the dialects that dist<strong>in</strong>guish between <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> /r/; (7) <strong>in</strong> a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> cases, Spanish /r/ or /d/ have been borrowed as <strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>fortis</strong> or <strong>lenis</strong> /l/.<br />

6. In the loanwords that only recently entered <strong>Zapotec</strong>, the pattern <strong>of</strong> borrow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

has changed considerably. First, recent loans naturally reflect changes undergone by the<br />

<strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong> American Spanish s<strong>in</strong>ce the sixteenth century. One <strong>of</strong> these is the<br />

velarization <strong>of</strong> the palatal sibilant //, reflected <strong>in</strong> early loans such as A (daa)ribeyi <<br />

arveja ‘pea’, to /x/. Second, prolonged exposure to the phonological system <strong>of</strong> Spanish<br />

due to extensive lexical borrow<strong>in</strong>g and massive bil<strong>in</strong>gualism have exercised a powerful<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence on the borrow<strong>in</strong>g strategies <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual dialects and <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> as a<br />

whole. Changes <strong>in</strong> the borrow<strong>in</strong>g pattern are partly due to the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> the<br />

phonemes /f/, /x/ (or /h/), and <strong>in</strong> some cases /r/ (e.g., <strong>in</strong> Coatlan <strong>Zapotec</strong>, cf. Rob<strong>in</strong>son<br />

1963) <strong>in</strong> the phonological systems <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects. Thus, while <strong>in</strong> earlier loans both<br />

/f/ and /x/ were rendered by stops (cf. YB lberg, SLQZ albe’erg < arveja ‘pea’), <strong>in</strong> more<br />

recent borrow<strong>in</strong>gs they are borrowed as fricatives (cf. MZ alberj ‘pea’). 11 Exposure to<br />

25

Spanish has also re<strong>in</strong>forced contrasts that existed <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> only at a subphonemic level,<br />

trigger<strong>in</strong>g rearrengements <strong>in</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong> native phonemes. Both types <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

can be observed when compar<strong>in</strong>g the treatment <strong>of</strong> Spanish consonants <strong>in</strong> the early and the<br />

more recent strata <strong>of</strong> borrowed vocabulary. Thus, <strong>in</strong> Cajonos <strong>Zapotec</strong> both voiced and<br />

voiceless Spanish obstruents are usually reflected <strong>in</strong> early loans as <strong>lenis</strong> (e.g. béy < paño,<br />

bd < Pedro); <strong>in</strong> recent loans Spanish voiceless stops are borrowed as <strong>fortis</strong>, and voiced<br />

stops as <strong>lenis</strong>. This borrow<strong>in</strong>g pattern has caused <strong>fortis</strong> /p/ to appear <strong>in</strong> word-<strong>in</strong>itial<br />

position, which it never does <strong>in</strong> native words, and has also led to a greater importance <strong>of</strong><br />

voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> contrast<strong>in</strong>g the two series <strong>of</strong> obstruents (cf. Nellis and Hollenbach 1980:93,<br />

104-05). 12 /r/ and /l/ <strong>in</strong> the same dialect sometimes replace each other <strong>in</strong> early borrow<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

(e.g. m:ál < comadre ‘godmother’, kórìs < coles ‘cabbages’), but <strong>in</strong> recent loans they are<br />

borrowed as /r/ and /l/, respectively, possibly due the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> a greater contrast<br />

between the two liquids ow<strong>in</strong>g to a steady flow <strong>of</strong> Spanish loans. Also, while <strong>in</strong> early<br />

loans Spanish trilled /r/ was borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong>, <strong>in</strong> later loans it can be rendered <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong><br />

by a <strong>fortis</strong> rhotic, cf. címa r < chamarra ‘blanket’ (an old loan) versu r:ey < raya ‘l<strong>in</strong>e’ (a<br />

recent loan). It has already been hypothesized above that <strong>fortis</strong> /r/ is a recent <strong>in</strong>novation<br />

<strong>in</strong> some <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects, conceivably triggered by a synchronic dissociation between<br />

<strong>lenis</strong> /r/ and its etymological <strong>fortis</strong> counterpart. It is also likely that this <strong>Zapotec</strong>-<strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

development received additional re<strong>in</strong>forcement from the existence <strong>of</strong> two rhotics <strong>in</strong><br />

Spanish loanwords.<br />

Dialects other than Cajonos <strong>Zapotec</strong> show comparable adjustments <strong>in</strong> their<br />

borrow<strong>in</strong>g strategies, generally <strong>in</strong> the direction <strong>of</strong> a greater attun<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Spanish. Among these may be mentioned the change <strong>in</strong> the render<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Spanish /n/ and<br />

26

l/: while <strong>in</strong> early loans these could be rendered with both <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong> native<br />

phonemes without a discernible distributional pattern, <strong>in</strong> later loans they are mostly<br />

borrowed as <strong>lenis</strong>. Some differences <strong>in</strong> the treatment <strong>of</strong> Spanish consonants <strong>in</strong> the early<br />

and late loans are summarized <strong>in</strong> Table 4.<br />

TABLE 4<br />

Changes <strong>in</strong> the Pattern <strong>of</strong> Consonant Borrow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Spanish consonants Early loans Recent loans<br />

______________________________________________________________________________________<br />

p-b, t-d, k-g borrowed as f or l; borrowed as f or l;<br />

voic<strong>in</strong>g unimportant borrow<strong>in</strong>g pattern<br />

for distribution based on voic<strong>in</strong>g<br />

s borrowed as l borrowed as f<br />

f borrowed as /p/, /b/ borrowed as /f/<br />

j [x/h] borrowed /g/ borrowed as [x/h]<br />

m borrowed as /m/ borrowed as /m/<br />

n borrowed as f or l borrowed as l<br />

l borrowed as f or l borrowed as l<br />

r borrowed as l borrowed as l<br />

rr borrowed as l borrowed as f or l<br />

7. This paper has exam<strong>in</strong>ed the adaptation <strong>of</strong> Spanish loanwords <strong>in</strong> various<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects. Although the ma<strong>in</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> the paper has been early loans, changes <strong>in</strong><br />

the borrow<strong>in</strong>g strategy that occurred between the earliest and the more recent layers <strong>of</strong><br />

loans have also been considered. A comparison <strong>of</strong> the borrow<strong>in</strong>g patterns dur<strong>in</strong>g these<br />

periods <strong>in</strong>dicates that contact with Spanish has exercized a considerable <strong>in</strong>fluence on<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>phonology</strong>, the most salient elements <strong>of</strong> which are the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> the<br />

phonemes /f/, /x/ and (possibly) /r/, trigger<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a greater importance <strong>of</strong> voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> opposition <strong>of</strong> obstruents (cf. Smith Stark 2000), changes <strong>in</strong> the distrubution <strong>of</strong><br />

/p/, (possibly) the creation <strong>of</strong> a greater contrast between /r/ and /l/, and phonemicization,<br />

<strong>in</strong> some dialects, <strong>of</strong> a <strong>fortis</strong> /r/.<br />

27

NOTES<br />

1 In addition to the dialects whose consonantal <strong>in</strong>ventories are presented <strong>in</strong> Table<br />

1, the phonological systems <strong>of</strong> Yalálag, Choapan, Atepec, Quioquitani, Elotepec, Zaniza,<br />

and Córdova’s (= 16 th -century Valley) <strong>Zapotec</strong> have also been exam<strong>in</strong>ed.<br />

2 I give here the consonantal <strong>in</strong>ventory <strong>of</strong> the more conservative Toledan dialect as<br />

it presents the greatest number <strong>of</strong> phonemic contrasts. While this is not essential with<br />

respect to such features as sibilant voic<strong>in</strong>g and the preservation <strong>of</strong> // as a separate<br />

phoneme (both lost by that time <strong>in</strong> the Old Castilian dialect), it is important for the<br />

contrastive status <strong>of</strong> /s (z)/ and / ()/ (which by that time had already merged <strong>in</strong><br />

Andalusian). And, even though this <strong>in</strong>ventory assumes that the old affricates /ts/ and /dz/<br />

had already given way to the correspond<strong>in</strong>g fricatives, at least two early loans provide<br />

support for their affricated pronunciation (see below). <strong>The</strong> only evidence for early yeísmo<br />

is provided by the treatment <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong> the word caballo ‘horse’. (On the <strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

sixteenth-century American Spanish see, e.g., Lapesa 1980:282ff, Rivarola 1991:450ff,<br />

Parodi 1995:39ff, and the extensive bibliography cited there<strong>in</strong>.)<br />

3 Córdova (1578a:73) notes what amounts to dialectal variation <strong>in</strong> this respect: “A<br />

la. r. hazen que sirua de. t. vt torobaya, pro totobaya. Ciroo, pro citao” (‘they make r<br />

serve as t, as <strong>in</strong> torobaya for totobaya, ciroo for citao’).<br />

4 Spanish loans <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>, unlike the contemporary borrow<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> Nahuatl (cf.<br />

González Cazanova 1977:144, 149), Mayan (cf. Parodi 1987:346-47 and 1995:50-51)<br />

and some other Mesoamerican languages (cf. Campbell 1991:171-72; Canfield 1934:210-<br />

16) do not give evidence <strong>of</strong> a phonemic difference <strong>in</strong> the pronunciation <strong>of</strong> /b/ (< Lat<strong>in</strong><br />

-p-, b-) and // (< Lat<strong>in</strong> -v-, -b-). <strong>The</strong> outcomes <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervocalic -b- <strong>in</strong> the word caballo <strong>in</strong><br />

28

the dialects which drop the pretonic vowel, such as Z (kwey) cannot be taken as an<br />

evidence <strong>of</strong> its fricativized pronunciation s<strong>in</strong>ce the native cluster /kb/ has the same<br />

outcome (cf. Z kwez, the Potential form <strong>of</strong> bez ‘to cry, to shout’).<br />

5 <strong>The</strong> agreement <strong>of</strong> several <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects makes it unnecessary to analyze the<br />

second part <strong>of</strong> the word as Ca yìσ& ‘grass’ (Nellis and Hollenbach 1980:104). Borrow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

through Nahuatl or another medium is likely <strong>in</strong> this case (cf. Nahuatl colex < Spanish<br />

coles cited <strong>in</strong> González Casanova 1977:151). Comparable forms <strong>in</strong> other Mesoamerican<br />

languages are quoted <strong>in</strong> Campbell (1991:176).<br />

6 In the treatment <strong>of</strong> Spanish <strong>in</strong>tervocalic /k/ or clusters conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g it Zaniza<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guishes three layers <strong>of</strong> loanwords. In the earliest layer, -/k/- > -g-, as <strong>in</strong><br />

vaca ‘cow’ > bàg. In a later layer, Sp. -/k/- > -j- (phonetically [h]), e.g. loco ‘mad’ > loj,<br />

Lucas > Lyúj, Francisco > Sijw (the treatment <strong>of</strong> Spanish /s/ here is also different from<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the earliest loans). In the most recent borrow<strong>in</strong>gs, Spanish -/k/- > Z -k-.<br />

7 In more recent loans, Spanish ch is borrowed as such <strong>in</strong> both Cajonos and Atepec<br />

(cf. Nellis and Hollenbach 104).<br />

8 <strong>Zapotec</strong> borrow<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> general are not a good source <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation on the<br />

voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> sibilants.<br />

9 Numerous other words, mostly names <strong>of</strong> objects new to Mesoamerican economy,<br />

conta<strong>in</strong> the word ‘Castilla’ as a component part, for example YB yetxtil ‘bread’ (yet<br />

‘tortilla’), za’axtil ‘pomegranate’ (za’a ‘ear <strong>of</strong> corn’), bi’oxtil ‘maggot’ (bi’o ‘flea’),<br />

yaxtil ‘tall reed’ (ya ‘reed’); ZooZ zaxtil ‘pomegranate’, yetextil ‘bread’; Co yokssttill<br />

‘soap’; A ettaxtila ‘bread’, daaxtila ‘(broad) bean’ (daa ‘(kidney) bean’), yua’xtila<br />

‘wheat’ (yua’ ‘maize’); SLQZ gueht x:tiilly ‘pan’, bihx:tiilly ‘soap’; MZ yätxtiil ‘bread’,<br />

29

säxtiil ~ zäxtiil ‘pomegranate’ (zä’ ‘ear <strong>of</strong> corn’), biäxtiil ‘soap’, bedzxtiil ‘m<strong>in</strong>t’ (bedz-<br />

‘seed <strong>of</strong> fruit’), manxanilxtiil ‘camomile sp.’.<br />

10 I thank Dr. Kev<strong>in</strong> Terraciano for suggest<strong>in</strong>g to me this etymology. Phonetically,<br />

the reduction <strong>of</strong> a four-syllable word to one syllable is not unusual (cf. T dì from Spanish<br />

melodía). As one <strong>of</strong> the strategies for adjust<strong>in</strong>g Spanish words to the mostly bisyllabic<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> vocabulary, there is a tendency, especially <strong>in</strong> early loans, to drop<br />

pretonic syllables (e.g. Z mìzh < camisa ‘shirt’; Co wai < caballo ‘horse’; Zoo lmet, YB<br />

lmet < limeta ‘bottle’; YB/Zoo migw, Z miw < amigo ‘friend’; A yèrù < agujero ‘hole’).<br />

In some cases, only the pretonic vowel drops (MZ mbaal, SLQZ mbaaly < compadre<br />

‘godfather’; YB/Zoo xcan, MZ xcaan < escaño ‘bench with a back’; Z kwey, T káy, Q<br />

gay < caballo ‘horse’; YB/Zoo dmigw < dom<strong>in</strong>go ‘Sunday’; YB rmech, SLQZ<br />

[…]rmuudy < remedio). This tendency, however, is counterbalanced by the many<br />

<strong>in</strong>stances <strong>in</strong> which the pretonic syllable or syllables have been preserved.<br />

11 Other examples <strong>of</strong> this borrow<strong>in</strong>g chronology <strong>in</strong>clude Co (kos)ak < ajo ‘garlic’<br />

(early shape <strong>of</strong> the word preserved e.g. <strong>in</strong> Z àzh); A mécú < bermejo ‘vermilion’, necu <<br />

conejo ‘rabbit’ (the more recent loan <strong>in</strong> A is cuneju; the orig<strong>in</strong>al palatal fricative is<br />

reflected, with metathesis, <strong>in</strong> Ca znékw), yèrù < *geru < agujero ‘hole’ (g- > y-/__i, e <strong>in</strong><br />

A; a sixteenth-century treatment <strong>of</strong> the same fricative can be seen <strong>in</strong> A gúψ)á < aguja<br />

‘needle’); T ãnk, SLQZ a’nngl < angel (cf. more recent T ãhy < Ángela, SLQZ<br />

Anjalye’nn < Angel<strong>in</strong>a).<br />

12 Explanation <strong>of</strong> the treatment <strong>of</strong> Spanish obstruents <strong>in</strong> recent loans <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong><br />

coexistent phonemic systems (cf. Fries and Pike 1949) is also possible. Such an<br />

30

explanation would assume that <strong>in</strong> the speech <strong>of</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>guals Spanish obstruents are<br />

contrasted as voiced and voiceless and native obstruents as <strong>fortis</strong> and <strong>lenis</strong>.<br />

31

APPENDIX<br />

(1) Spanish loanwords were exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Zapotec</strong> dialects:<br />

(a) Northern: Atepec (A), Cajonos (Ca), Yatzachi El Bajo (YB), Zoogocho (Zoo);<br />

(b) Central: Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong> (I), Mitla (MZ), San Lucas Quiav<strong>in</strong>í <strong>Zapotec</strong> (SLQZ);<br />

(c) Southern: Santa María Coatlán <strong>Zapotec</strong> (Co), Quiegolani (Q);<br />

(d) Westerm: San Lorenzo Texmelucan <strong>Zapotec</strong> (T), Zaniza <strong>Zapotec</strong> (Z).<br />

<strong>The</strong>re have been only two studies devoted to Spanish loanwords <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong>,<br />

Fernández’ (1965) paper on Mitla and Pickett’s (1992) article on Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong>. <strong>The</strong><br />

other loans on which the present study is based were culled from various dictionaries and<br />

wordlists, as follows:<br />

Atepec: Neil Nellis and Jane Goodner de Nellis. 1983. Diccionario zapoteco de Juarez.<br />

México, D.F.: Instituto L<strong>in</strong>güístico de Verano;<br />

Cajonos: Nellis and Hollenbach 1980;<br />

Yatzachi El Bajo: Butler, Inez M. 1997. Diccionario zapoteco de Yatzachi. Tucson, AZ:<br />

Instituto L<strong>in</strong>güístico de Verano;<br />

Zoogocho: Long, Rebecca C., and S<strong>of</strong>ronio Cruz M. 1999. Diccionario zapoteco de San<br />

Bartolomé Zoogocho, Oaxaca. Instituto L<strong>in</strong>güístico de Verano.<br />

Isthmus: Pickett, Velma B. 1992. Palabras de préstamo en zapoteco del Istmo. Scripta<br />

philologica <strong>in</strong> honorem Juan M. Lope Blanch, ed. Elizabeth Luna Traill, pp. 69-<br />

76. México: UNAM // Pickett, Velma et al. 1979. Vocabulario zapoteco del<br />

Istmo. México, D.F.: Instituto L<strong>in</strong>güístico de Verano;<br />

Mitla: Fernández de Miranda, María Teresa. 1965. Préstamos españoles en el zapoteco de<br />

Mitla. AINAH 17:259-73 // Stubblefield, Morris, and Carol Miller de<br />

32

Stubblefield. Diccionario zapoteco de Mitla, Oaxaca. México, D.F.: Instituto<br />

L<strong>in</strong>güístico de Verano;<br />

SLQZ: Munro and Lopez 1999;<br />

Coatlán: Rob<strong>in</strong>son 1963;<br />

Quiegolani: Regnier 1993;<br />

Texmelucan: Speck, Charles H. 1978. <strong>The</strong> <strong>phonology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Texmelucan <strong>Zapotec</strong> verb<br />

irregularity. M.A. thesis, University <strong>of</strong> North Dakota;<br />

Zaniza: author’s field notes.<br />

(2) <strong>The</strong> most recurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the early Spanish loans belong to several lexical<br />

categories. <strong>The</strong> loanwords that may have entered <strong>Zapotec</strong> later than the sixteenth century<br />

are given <strong>in</strong> brackets.<br />

Plants and foodstuffs: aceite, ajo, arveja, arroz, azúcar, col, (cuajo), culantro, chocolate,<br />

(durazno), garbanzo, granada, mezcal, mole, mostaza, naranja, pan,<br />

panela, papaya, queso, sandía, trigo.<br />

Animals: caballo, cochi, conejo, chivo, macho, mico, micho, mula, nigua,<br />

novillo, pollo, (toro), vaca, yegua.<br />

Utensils and the like: aguja, almohada, batea, (bolsa), botón, canoa, clavija, cuchara,<br />

cuchillo, escaño, esqu<strong>in</strong>a, estaca, (gancho), garrote, (horno), jabón,<br />

jarro, jícara, lazo, limeta, machete, mazo, mecha, mesa, mol<strong>in</strong>illo,<br />

(muñeca), navaja, paño, plato, servilleta, silla, silla de montar,<br />

(surco), taza, teja, tijeras, timón, (tienda, t<strong>in</strong>ta, tiro, trompo).<br />

Dress: camisa, (c<strong>in</strong>cho, c<strong>in</strong>ta), media, sombrero, zapato.<br />

33

Pr<strong>of</strong>essions/<strong>in</strong>stitutions:albañil, alcalde, banco, capitán, Castilla, (ciudad), coc<strong>in</strong>ero,<br />

escuela, mozo, pastor, soldado, testigo.<br />

Money: d<strong>in</strong>ero, maravedí, medio, peso, tomín, real.<br />

Religion: anima, amigo, comadre, compadre, cruz, dios, gigante, misa,<br />

remedio, sacristán, santo, (vicio), vigilia.<br />

Calendar: dom<strong>in</strong>go, (lunes, sábado), semana, (tiempo).<br />

Adjectives and misc.: (azul), barato, hasta, (loco), manso, morado.<br />

Proper names: Andrés, José, Juan, Juana, Lucas, Luis, Luisa, mixe, Pablo, Pedro,<br />

Tomás.<br />

34

REFERENCES<br />

Avel<strong>in</strong>o, Heriberto. 2001. <strong>The</strong> phonetic correlates <strong>of</strong> <strong>fortis</strong>-<strong>lenis</strong> <strong>in</strong> Yalálag <strong>Zapotec</strong><br />

consonants. M.A. thesis, UCLA.<br />

Benton, Joseph. 1988. Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>phonology</strong>. Ms.<br />

Broadwell, Aaron. 2000. Fortis/<strong>lenis</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ctions <strong>in</strong> early <strong>Zapotec</strong>an manuscripts. Paper<br />

read at the conference La voz <strong>in</strong>dígena de Oaxaca, Los Angeles, 19-20 May 2000.<br />

Campbell, Lyle. 1991. Los hispanismos y la historia fonética del español en América. El<br />

español en América: actas del III Congreso Internacionald del Español de<br />

América, ed. C. Hernández et al., vol. 1, pp. 171-179. Valladolid: Junta de<br />

Castilla y León.<br />

Canfield, Delos L<strong>in</strong>coln. 1934. Spanish literature <strong>in</strong> Mexican languages as a source for<br />

the study <strong>of</strong> Spanish pronunciation. New York: Instituto de las Españas en los<br />

Estados Unidos.<br />

Córdova, Juan de. 1886 [1578a]. Arte del idioma zapoteco. Facsimile edition. México:<br />

Ediciones Toledo.<br />

_____. 1886 [1578b]. Vocabvlario en lengva çapoteca. Facsimile edition. México:<br />

Ediciones Toledo.<br />

Diccionario zapoteco-español: reglas para el entendimiento de las variantes dialectales de<br />

la sierra hecho por los zapotecos de la variante del sector xhon. 1995.Yojovi,<br />

Solaga, Oaxaca: Zanhe Xbab SA, A.C.<br />

Fries, Charles C., and Kenneth L. Pike. 1949. Coexistent phonemic systems. Language<br />

25:29-50.<br />

González Casanova, Pablo. 1977. Estudios de l<strong>in</strong>güística y filología nahuas, ed.<br />

Ascensión H. de León-Portilla. México: UNAM.<br />

Jaeger, Jeri J. 1983. <strong>The</strong> <strong>fortis</strong>/<strong>lenis</strong> question: evidence from <strong>Zapotec</strong> and Jawoñ. Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Phonetics 11:177-89.<br />

Kaufman, Terrence. 1994. Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> reconstructions. Ms.<br />

_____. 1983. New perspectives on comparative Otomanguean <strong>phonology</strong>. Ms.<br />

_____. n.d. <strong>The</strong> <strong>phonology</strong> and morphology <strong>of</strong> <strong>Zapotec</strong> verbs. Ms.<br />

Lapesa, Rafael. 1980. Historia de la lengua española. 8 th ed. Madrid: Gredos.<br />

35

Manrique Castañeda, Leonardo. 1966-67. El zapoteco de fray Juan de Córdoba. Anuario<br />

de Letras 6:203-11.<br />

Marlett, Stephen A., and Velma B. Pickett. 1987. <strong>The</strong> syllable structure and aspect<br />

morphology <strong>of</strong> Isthmus <strong>Zapotec</strong>. IJAL 53:398-422.<br />

Munro, Pamela, and Felipe H. Lopez. 1999. Di’csyonaary X:tèe’n Dìi’zh Sah Sann<br />

Lu’uc/San Lucas Quiav<strong>in</strong>í <strong>Zapotec</strong> dictionary/Diccionario zapoteco de San Lucas<br />

Quiav<strong>in</strong>í. UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.<br />

Nellis, Donald G., and Barbara E. Hollenbach. 1980. Fortis versus <strong>lenis</strong> <strong>in</strong> Cajonos<br />

<strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>phonology</strong>. IJAL 46:92-105.<br />

Parodi, Claudia. 1995. Orígenes del español americano. Vol. 1. Reconstrucción de la<br />

Pronunciación. México: UNAM.<br />

_____. 1987. Los hispanismos en las lenguas mayances. Studia humanitatis: homenaje a<br />

Rubén Bonifaz Nuño, ed. A. Ocampo, pp. 339-49. México: UNAM.<br />

Pickett, Velma B., et al. 1998. Gramática popular del zapoteco del Istmo. Juchitán,<br />

México: Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo B<strong>in</strong>nizá A.C. and Tucson, AZ:<br />

Instituto L<strong>in</strong>güístico de Verano.<br />

Regnier, Sue. 1993. Quiegolani <strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>phonology</strong>. SIL-University <strong>of</strong> North Dakota<br />

Work Papers 37:37-63.<br />

Rivarola, José Luis. 1991. En torno a los orígenes del español de América. Scripta<br />

philologica <strong>in</strong> honorem Juan M. Lope Blanch, ed. Elizabeth Luna Traill, vol. 1,<br />

pp. 445-68. México: UNAM.<br />

Rob<strong>in</strong>son, Dow F. 1963. Field notes on Coatlan <strong>Zapotec</strong>. Hartford Sem<strong>in</strong>ary Foundation.<br />

Smith Stark, Thomas C. 2000. La ortografía del zapoteco en el Vocabvlario de fray Juan<br />

de Córdova. Ms.<br />

Suárez, Jorge A. 1973. On Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong> <strong>phonology</strong>. IJAL 39:236-49.<br />

Swadesh, Morris. 1947. <strong>The</strong> phonemic structure <strong>of</strong> Proto-<strong>Zapotec</strong>. IJAL 13:220-30.<br />

36