Session 4a

Session 4a

Session 4a

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

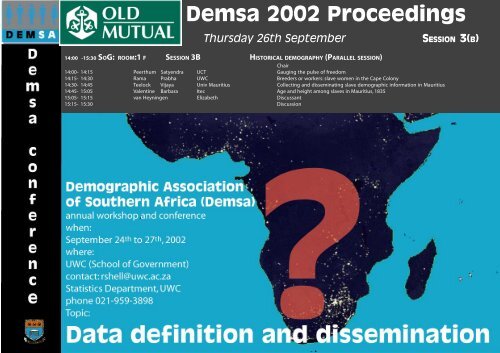

Historical demography Demsa 2002 Proceedings<br />

Thursday 26th September SESSION 3(B)<br />

14:00 -15:30 SOG: ROOM:1 F SESSION 3B HISTORICAL DEMOGRAPHY (PARALLEL SESSION)<br />

Chair<br />

14:00- 14:15 Peerthum Satyendra UCT Gauging the pulse of freedom<br />

14:15- 14:30 Rama Prabha UWC Breeders or workers: slave women in the Cape Colony<br />

14:30- 14:45 Teelock Vijaya Univ Mauritius Collecting and disseminating slave demographic information in Mauritius<br />

14:45- 15:05 Valentine Barbara Itec Age and height among slaves in Mauritius, 1835<br />

15:05- 15:15 van Heyningen Elizabeth Discussant<br />

15:15- 15:30 Discussion<br />

1

2 <strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)

Historical demography<br />

“Gauging the Pulse of Freedom”:<br />

A Study of Manumission in Mauritius, the<br />

Cape Colony, and Jamaica during the Early<br />

Nineteenth Century:<br />

A Comparative Perspective<br />

By Satyendra Peerthum,<br />

University of Mauritius.<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

Abstract<br />

The objective of this research paper is to compare and contrast the<br />

manumission rates and patterns of Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and<br />

Jamaica between the 1810s and the early 1830s. By analysing these<br />

manumission rates and patterns, this study tries to indicate in which<br />

slave society, the slaves stood the best chance of obtaining their freedom<br />

through manumission. Within a comparative framework, it looks at<br />

urban and rural manumission, male and female manumission, the<br />

manumission of creole and foreign-born slaves as well as gratuitous and<br />

bought manumissions in these three slave societies. This research paper<br />

also examines the manumission patterns among the different segments<br />

of the slave populations of Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica.<br />

Furthermore, it also carries out a thorough demographic analysis of the<br />

slave populations of these three British colonies. It focuses a great deal<br />

on the impact of British slave amelioration legislation on these three<br />

slave societies through the liberalization of the colonial manumission<br />

laws and the work of the Protector of Slaves in this important process.<br />

This research paper shows that during the 1820s and early 1830s, in<br />

Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica, an increasing number of<br />

slaves were purchasing their freedom. It also highlights the fact that<br />

during this period, thousands of slaves were able to secure their freedom<br />

before the abolition of slavery. This study analyses the social and<br />

economic factors which influenced the manumission rates and patterns<br />

in these three slave societies.<br />

3

4 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

Introduction: Manumission<br />

and the Openness of Slave Societies<br />

During the second half of the twentieth century, the comparative studies<br />

of New World slave societies “have used manumission rates as a cornerstone<br />

for the argument that Latin American slavery was a much more fluid<br />

and open institution” than slavery in the American South and the British<br />

Caribbean islands. 1 In 1947, Frank Tannenbaum was the first American<br />

slave historian to discuss the concept of the openness of slave societies. He<br />

carried out a comparative study of Brazilian slavery with North American<br />

slavery. Tannenbaum came to the conclusion that the slaves in Brazil had<br />

more opportunities of being manumitted and in achieving social mobility<br />

than the slaves in the American South. Therefore, the extent to which<br />

freedom was accessible to the slaves, through manumission, has been<br />

considered by slave historians as one of the crucial indicators (or indexes)<br />

of the openness of a slave society. 2 A slave society with low manumission<br />

rates, or where manumissions were not frequent, was a clear indicator that<br />

the slaves in that society had extremely few chances of becoming free and<br />

in achieving some type of social mobility. But, at the same time, a slave<br />

society with high levels of manumission, or where manumissions were very<br />

frequent, shows that the slaves in that society had much greater chances of<br />

becoming free and in achieving social mobility. Thus, a slave society with<br />

high manumission rates was seen as a more open slave society than one<br />

with low manumission rates. 3 South African historians such as Robert<br />

Shell, Richard Elphick, and Nigel Worden have also used manumission<br />

rates to show that a closed and rigid slave colonial society existed, during<br />

the eighteenth century, at the Cape of Good Hope under VOC rule. 4<br />

David Brion Davis, a famous slave historian, explains that “the ease and<br />

frequency of manumission” seem to provide the “crucial standard in<br />

measuring the relative harshness of slave systems”. 5 According to him,<br />

manumission rates, or the number of slaves freed in a slave society each<br />

year or over a number of years, provided the yardstick with which one<br />

could measure the harshness of slavery in slave societies. But Eugene<br />

Genovese, another well known American slave historian, points out, in his<br />

famous criticism of Davis’ observation on manumission, that it is extremely<br />

difficult to make a judgment and to measure the severity and harshness of<br />

slave systems. The best historians can do is to contrast and to “compare<br />

specific kinds of treatment and their consequences, instead of trying to use<br />

a single standard of judgment”.<br />

In a very influential article on the application of the comparative method<br />

to different slave societies, Genovese distinguished between three meanings<br />

of the treatment of slaves in the slave societies. The first involved the<br />

“day-to-day living conditions” which included such things as housing and<br />

working conditions as well as quality and quantity of food and clothing.<br />

The second one was their “conditions of life”, or in other words, the<br />

conditions of the lives of the slaves pertaining to such things as opportunities<br />

for independent social, religious, and family life as well as family<br />

security and the evolution of cultural developments. The third and last one<br />

deals with “access to freedom and citizenship” or the access of the slaves<br />

to freedom and citizenship in different slave societies. 6 Robert Shell explains<br />

that in:<br />

“Genovese’s view this was the critical aspect of the treatment of all slaves<br />

everywhere” and “scholars of comparative slavery should evaluate the<br />

harshness or otherwise of slavery according to these criteria: they should<br />

never confuse them”. 7<br />

For his part, Nigel Worden explains that during the 1700s and early<br />

1800s, one of the markers of the way in which the slaves were treated in<br />

Mauritius and the Cape Colony was their “access to freedom” through<br />

manumission and also “the status of the freed slaves”. 8<br />

This conference paper will focus on the access of the Mauritian, Cape,<br />

and Jamaican slaves to freedom, through manumission. However, this<br />

research paper also clearly acknowledges the fact that the analysis of<br />

manumission rates must also be combined with “an analysis of the quality<br />

of the ex-slaves’ freedom”. 9

Historical demography<br />

Quantitative History & Its Application<br />

Quantitative history, or “history by numbers”, is based on the belief that<br />

“in making quantitative statements, historians should take the trouble to<br />

count rather” than “content themselves with impressionistic estimates”.<br />

During the twentieth century, almost all the branches of historical research<br />

have been affected by quantitative history such as economic, social, and<br />

demographic history. Basically, when historians use quantitative methods<br />

The growth of the Caribbean<br />

plantation culture<br />

Jamaica in 1710<br />

(above)<br />

and in 1790<br />

(below).<br />

Each dot equals<br />

one plantation<br />

Source: Michael Craton, Searching for the Invisible Man, pages 12-13.<br />

in their books and articles, there is a fundamental shift from focusing on<br />

individuals to masses, since they use numbers to study whole groups of<br />

people. Furthermore, last forty years, computers and computer programs<br />

developed very rapidly and they became cheaper and more accessible to<br />

historians. It became much easier to feed, process, and analyse statistical<br />

data which allowed for quantitative exercises. Thus, gradually, the use of<br />

quantitative methods became an integral part of historical research. 10<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

One of the criticisms that has been brought against the use of this method<br />

is that “by emphasizing the common factors in mass behaviour, at the<br />

expense of the individual and the exceptional, has a ‘dehumanizing’ effect<br />

on history”. In addition, some traditional historians have also argued that<br />

the use of quantitative history in academic studies is that it “distorts our<br />

view of the past by directing attention to those sources which readily<br />

respond to statistical analysis at the expense of those which do not”. 11<br />

Therefore, what is often implied by traditional historians, who are often<br />

critical of quantitative history, is that it uses a limited number of primary<br />

sources and gives a limited view of history. 12<br />

But John Tosh explains:<br />

It is sometimes imagined that the application of quantitative methods<br />

on a large scale displaces traditional skills of the historian and calls<br />

for an entirely new breed of scholar. Nothing could be further from<br />

the truth. Statistical know-how can only be effective if it is treated as<br />

an addition to the historian’s tool-kit, and subject to the normal<br />

controls of historical method. 13<br />

After all, over the decades, historians have gradually recognized the<br />

contribution which quantitative history can make to traditional historical<br />

approaches and explanations. Indeed, social historians can carry out indepth<br />

studies of certain societies, such as colonial slave societies, by<br />

drawing their information from archival documents and other primary<br />

sources, while at the same time, supplementing their findings with quantitative<br />

analysis of the figures which may be found in some of these<br />

sources. 14 This is precisely the aim of this chapter on quantitative<br />

manumission.<br />

John Marincowitz accurately explains: “ ‘Quantitative history’ and ‘People’s<br />

history’ need not be conflicting historical methods”. 15 In order to<br />

give substance to this argument, it is important to point out that, in recent<br />

decades, a large number slave studies have been produced and “the most<br />

important developments in quantitative historical methods have been<br />

disproportionately concentrated in this area”. During the 1960s and after,<br />

5

6 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

most of the slave studies which have used quantitative methods have<br />

concentrated on the Atlantic slave trade and the slave societies of the<br />

Americas. 16<br />

In 1969, in The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census, Philip Curtin carried out<br />

estimates of the number of slaves who were shipped from Africa to the<br />

New World slave societies between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.<br />

17 Just five years later, R.W. Fogel and S.L. Engerman, two American<br />

intellectuals, published their two volume book, Time on the Cross, which<br />

is still considered to be a controversial work. Over the course of several<br />

years, these two historians examined and gathered statistical data from<br />

plantation records, probate records, census schedules, and other primary<br />

sources. By using the statistical data from these sources, Fogel and<br />

Engerman put forward certain controversial conclusions. These two American<br />

historians concluded that in the mid-1800s, the white planters of the<br />

American South formed part of a humane and rational capitalist class and<br />

that their slaves were a well-treated and prosperous labour-force. 18<br />

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, slave studies gradually began to<br />

focus on other parts of Africa such as East Africa, South Africa, Mauritius,<br />

and Madagascar. 19 It is evident that quantitative history has had a huge<br />

impact on some of the historians who have written on slavery in Mauritius,<br />

the Cape Colony, and Jamaica. In Mauritian slave historiography, this can<br />

be seen in the works of Rene Kuczynski, Brenda Howell, Daniel North-<br />

Coombes, Anthony Barker, Vijaya Teelock, and Richard B. Allen. In Cape<br />

slave historiography, this fact is clearly reflected in the books and articles<br />

of Robert Shell, Robert Ross, Nigel Worden, Mary Rayner, and Andrew<br />

Bank. In Jamaican slave historiography, this can also be seen in the academic<br />

studies of Barry Higman, William Green, and others (Refer to<br />

Endnotes). Therefore, slave historians can use quantitative history to gain<br />

a greater understanding of the slave populations and the slave societies<br />

they are studying. 20 The most important and greatest contribution of<br />

quantitative history has been made in the field of demographic history. 21<br />

It is the premise of this conference paper that a better understanding can<br />

be reached about the slave populations of Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and<br />

Jamaica, by analyzing the statistical data from the manumission records<br />

which can be used to reinforce the information from other primary<br />

sources. 22 Thus, in order to get a clearer picture of the slave populations<br />

as well as the slave societies of Mauritius, the Cape, and Jamaica, mostly<br />

between the 1810s and early 1830s, the author has resorted to using<br />

quantitative manumission which falls within the sphere of quantitative<br />

history. 23<br />

John Tosh eloquently explains: “at its most ambitious, quantitative history<br />

seeks to elucidate an entire historical process by measuring” and comparing<br />

certain relevant factors. 24 This research paper tries to use quantitative<br />

history to shed some light on a number of questions such what were the<br />

manumission rates in Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica during the<br />

early nineteenth century? To what extent can manumission rates be used<br />

as one of the major indicators of the openness of a slave society? What<br />

were some of the manumission patterns among the different segments of<br />

the slave population? Who were the slaves who bought their freedom and<br />

which slaves stood the best chance of being manumitted? Finally, what<br />

was the impact of the liberalization of manumission process during the late<br />

1820s and early 1830s? 25<br />

When using quantitative history in a study, it is important first to establish<br />

the reliability and comparability of the statistical data and it is essential<br />

that, “the historian seeks out data from varied and scattered source materials”.<br />

Once the historian has analyzed the sources and has recorded the<br />

figures which they consider as being reliable, comparable, and representative<br />

of the people and society being studied, then the data can be tabulated.<br />

26 For this conference paper, the manumission figures were taken<br />

from the official colonial manumission returns from the Mauritius Archives<br />

and the Reports of the Protector of Slaves of Mauritius and the Cape<br />

Colony which are printed in the British Parliamentary Papers. Additional

Historical demography<br />

manumission returns were also obtained from certain colonial dispatches<br />

and contemporary observers. For Jamaica, the manumission data was<br />

taken entirely from the secondary sources. 27<br />

The statistical data, while being tabulated, must be presented in such a<br />

way so that as much information can be extracted from them as possible. 28<br />

Furthermore, the manumission data has to be presented in a way that<br />

shows the frequency of manumission of different slave societies. According<br />

to Orlando Patterson, there are two kinds of issues which are involved<br />

when using and analyzing the frequency of manumission in a study of<br />

slave societies. Firstly, the manumission data has to show the variations in<br />

the manumission rates of different slave societies. 29 This paper compares<br />

and contrasts the manumission rates of Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and<br />

Jamaica, mostly between the 1810s and 1830s. Thus, within a comparative<br />

framework, it tries to look at the frequency of manumission in these<br />

three British slave societies and it tries to point out in which slave society,<br />

the slaves were being manumitted most frequently. This may give an<br />

indication which one of these three British colonies, by allowing their<br />

slaves greater access to freedom through manumission, had a more open<br />

slave society. 30<br />

Secondly, Patterson explains that when looking at the frequency of<br />

manumission, the historian has to focus on “the varying rates among<br />

different groups of individuals within societies, regardless of the overall<br />

rate of manumission”. 31 When it comes to analyzing manumission in<br />

Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica, this study doesn’t look at these<br />

colonial slaves as one homogenous mass. It is important to note that one of<br />

the major weaknesses in most of the historical studies on Mauritian slavery<br />

has been the tendency of seeing the Mauritian slaves as being one homogenous<br />

mass. 32 Some of the manumission figures in this research paper<br />

clearly show that the Mauritian, Cape, and Jamaican slave populations<br />

were diverse in their ethnicity, demographic composition, and occupation.<br />

Therefore, it looks in detail at the manumission patterns of the male,<br />

female, urban, rural, local-born, and foreign-born slaves in these three<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

British slave colonies, mostly between the 1810s and the early 1830s. In<br />

addition, this paper also makes a distinction between local-born or creole<br />

slaves, Mozambican, Malagasy, Indian, and Malay slaves. It is evident that<br />

such an approach highlights the racial and ethnic diversity of the slave<br />

populations and, to a certain extent, give an insight into the diversity of the<br />

slave experience in Mauritius, the Cape, and Jamaica.<br />

Quantitative Manumission and its Application<br />

In this conference paper, the presentation and analysis of the<br />

manumission data, as variations in the manumission rates of Mauritius, the<br />

Cape Colony, and Jamaica as well as the manumission rates among the<br />

different segments of their slave populations, will be called quantitative<br />

manumission. Thus, quantitative manumission, which falls within the<br />

sphere of quantitative history and as a tool of historical analysis, allows<br />

slave historians to compare and contrast the manumission rates of different<br />

slave societies and among the different segments of their slave populations.<br />

This comparative approach allows the slave historian to know in which of<br />

these three slave societies, manumission was frequent or not so frequent,<br />

the greatest of number of slaves who were freed, and the slaves who had<br />

the best chance of being manumitted.<br />

In this paper, quantitative manumission is used to how many slaves obtained<br />

their freedom through self-purchase as well as with the help of their<br />

free coloured relatives and those who were freed gratuitously by their<br />

owners. It will indicate how many female, male, creole, foreign-born,<br />

urban, and rural slaves were manumitted in each of these three British<br />

colonies. Therefore, quantitative manumission allows the slave historian to<br />

compare and contrast the frequency of manumission among the different<br />

segments of the slave populations of Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and<br />

Jamaica during the early nineteenth century. Furthermore, it also helps<br />

7

8 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

the historian to identify those slaves who stood the best chance of obtaining<br />

their manumission and eventually becoming free coloured members of<br />

these colonial societies.<br />

Quantitative manumission allows the slave historian to study the increases<br />

and decreases in the manumission rates during the early nineteenth century<br />

in Mauritius, the Cape, and Jamaica. This fact takes on an even<br />

greater importance, when looking at the introduction of British slave<br />

amelioration legislation which liberalized the restrictive manumission laws<br />

in these three British colonies during the late 1820s and early 1830s.<br />

Without doubt, quantitative manumission gives a clear indication, during<br />

the last decade of British colonial slavery, the overall impact the introduction<br />

of British amelioration legislation had on the manumission rates, on<br />

the access of the slaves to freedom, and the manumission process in these<br />

three slave societies. 33<br />

Christopher Saunders explains: “Historians of slavery at the Cape may lay<br />

too great a stress on the great day of freedom, whether 1 December 1834<br />

or the more important day four years later. Freedom had come to many<br />

individuals long before either of those dates, both those manumitted from<br />

slavery…and to the Prize Negroes. Individually and collectively they<br />

moved from effective slavery to “freedom” before emancipation dawned<br />

for the slaves”. 34 Thus, one of the main objectives of this paper is to place<br />

a great deal of emphasis on the fact that even before the abolition of<br />

slavery, thousands of Mauritian, Cape, and Jamaican slaves were able to<br />

obtain their freedom between the 1810s and the 1830s. This was especially<br />

the case during the late 1820s and early 1830s, with the liberalization<br />

of the manumission process for the slaves. 35<br />

Quantitative Manumission in Mauritius, at<br />

the Cape, and Jamaica: A Comparative Perspective<br />

In May 1827, the Franco-Mauritian planters sent an official letter to<br />

Governor Colville in which they outlined their views on the application of<br />

British slave amelioration legislation in Mauritius. When it came to the<br />

issue of easing the manumission process for the slaves, the white<br />

slaveowners remarked that “there is no colony in which, everything taken<br />

into consideration, so many manumissions occur as in Mauritius”. 36 This<br />

statement by the Mauritian planters was clearly an exaggeration because,<br />

as David Brion Davis points out, the “slaves in Latin America had more<br />

opportunities for manumission than did those in the British colonies or the<br />

United States”. 37 In fact, many more slaves were being manumitted in<br />

Brazil as well as in the Dutch colonies of Suriname and Curacao than in<br />

Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica. 38 For his part, Robert Shell<br />

points out that “the Cape manumission rate was higher than most of the<br />

anglophone Caribbean colonies, for example, the rate of Jamaica”. 39<br />

For a British slave colony, Mauritius had an unusually high manumission<br />

rate. 40 After all, in 1832, 1,647 slaves were manumitted, the greatest<br />

number of slaves to be free, in one year, during the entire period that<br />

slavery existed in the island. 41 This contrasts with the Cape’s highest<br />

manumission figure for one year, which was in 1827, when 245 slaves<br />

were freed. The figure for the Cape Colony is almost seven times lower<br />

than the highest Mauritian manumission figure for one year. 42 In Jamaica,<br />

the greatest number of slaves were manumitted between 1826 and 1829,<br />

around 1117 were freed or an annual average of 372. The highest<br />

manumission figure for Jamaica for one year was four and a half times<br />

lower than the highest Mauritian manumission figure for one year (See<br />

Appendix to this Paper). 43 During the late 1820s and early 1830s, when<br />

compared with the first half of the 1820s, the Mauritian manumission rate<br />

increased by six fold, at the Cape of Good Hope, it almost tripled, and in<br />

Jamaica, it rose by more than 26%. It is evident that between 1829 and

Historical demography<br />

1834, Mauritius had a much higher manumission rate which meant that<br />

more slaves were being freed when compared with the Cape Colony and<br />

Jamaica. It also shows that the Mauritian slaves had the greater access to<br />

freedom, through manumission, and many more former slaves were<br />

becoming members of the island’s free coloured community than their<br />

Cape and Jamaican counterparts. Thus, these facts reinforce the argument<br />

that during last years of British colonial slavery, to a certain extent, Mauritius<br />

had an open slave society. Furthermore, during this period, the British<br />

slave amelioration legislation, dealing with manumission, had a much<br />

greater impact in Mauritius than at the Cape of Good Hope and in Jamaica.<br />

44<br />

The Nature of Manumission in Three British<br />

Slave Colonies<br />

In the Cape Colony, between 1816 and 1822, out of 192 acts of<br />

manumission, “17 were effected by purchase and 175 by voluntary<br />

grants”. This meant that 91% were gratuitous manumissions which were<br />

granted by the slaveowners and 9% were bought manumissions which had<br />

been bought by the slaves themselves as well as with the help of their<br />

relatives. 45 In Jamaica, it was already mentioned, that in the early nineteenth<br />

century, there was some easing in the island’s manumission law. 46<br />

Thus, between 1807 and early 1820s, the overwhelming majority of the<br />

manumissions were bequests and voluntary grants by the slaveowners and<br />

not purchases by the slaves. 47 During the same period, this manumission<br />

trend at the Cape and in Jamaica was similar to what was taking place in<br />

Mauritius. Between 1811 and July 1822, there were 1,595<br />

manumissions, around 1061 slaves or 66.5% were manumitted by their<br />

owners. As for the rest, around 504 slaves or 31.6% were freed through<br />

marriages, self-purchase, and manumitted by their relatives and loved<br />

ones and 30 slaves or 1.9% were manumitted by the British government<br />

of Mauritius. 48 Therefore, during this period, most of the slaves were freed<br />

by their owners but, this was a manumission trend which was gradually<br />

going to change in Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica. 49<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

Between 1821 and 1826, there were 433 acts of manumission, around<br />

133 slaves or 30.7% were manumitted by their owners. In addition, 274<br />

slaves or 63.3% were freed through self-purchase, marriages, and with the<br />

financial help of their relatives. 50 It is evident that, during the first half of<br />

the 1820s, the number of slaves being freed through self-purchase, marriage,<br />

and with the aid of their relatives increased dramatically, when<br />

compared with the period between 1811 and 1822. At the same time,<br />

during the 1820s, the number of slaveowners who were manumitting their<br />

slaves declined gradually when compared with the first decade of British<br />

rule in Mauritius. 51<br />

Between 1817 and 1824, at the Cape, the number of slaves being freed<br />

by their owners was also gradually decreasing. 52 By the early 1820s, in<br />

Jamaica, the number of slaves being manumitted by the slaveowners<br />

declined and the number of slaves purchasing their freedom was increasing.<br />

53 This gradual reduction in the number of gratuitous manumissions by<br />

slaveholders in Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica, during the<br />

1820s, also coincided with a period when there was a brief decline in the<br />

manumission rates in these three slave societies. 54 In Mauritius, the<br />

number of slaves being manumitted declined from 172 in 1821 to an alltime<br />

low of 52 in 1823 and 40 in 1825. 55 At the Cape, according to the<br />

figures provided by Isobel Edwards, the number of slaves who were<br />

manumitted, annually, declined from 97 in 1817 to 27 in 1821 and 24<br />

in 1824. 56 For Jamaica, between 1817 and 1820, 1016 slaves were<br />

manumitted and from 1820 to 1823, only 921 slaves were freed. 57 It<br />

must be remembered that during the 1820s, the British imperial government<br />

implemented its slave amelioration laws to reform colonial slavery.<br />

Without a doubt, as it was mentioned earlier, these measures made the<br />

slaveowners in the British slave colonies even more reluctant to free their<br />

slaves.<br />

By the late 1820s, Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica moved<br />

towards a liberalization of their manumission laws which increased their<br />

manumission rates. 58 By 1826, in Mauritius, the number of slaves who<br />

9

10 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

were freed was 94 and, the following year, this figure rose to 190. 59<br />

Between March 1829 and December 1830, around 1,025 slaves were<br />

manumitted. 60 At the Cape, in 1826 and 1827, 210 slaves were freed. 61<br />

In Jamaica, between 1826 and 1829, around 1117 slaves were<br />

manumitted. 62<br />

Between August and December 1826, at the Cape of Good Hope, around<br />

63 slaves were manumitted and 31 or 49% among them had bought their<br />

freedom through their own savings as well as with the help of their relatives.<br />

63 In addition, from August 1826 to December 1832, as it was<br />

mentioned earlier, around 36.9% of the slaves had bought their freedom<br />

and over 37.8% were manumitted by their owners. 64 Therefore, when<br />

compared with the period from 1816 to 1822, the number of slaves who<br />

purchased their own freedom, between 1826 and 1832, more than quadrupled<br />

from 9% to 36%. 65 Indeed, at the Cape Colony, the liberalization<br />

of the manumission process allowed hundreds of slaves to purchase their<br />

freedom as well as for many free coloureds to manumit of their enslaved<br />

relatives. 66<br />

Barry Higman explains that in Jamaica “the number of manumissions<br />

purchased exceeded the number granted gratuitously from about 1826”. 67<br />

Between 1826 and 1833, 2479 Jamaican slaves were manumitted and<br />

well over half of these slaves managed to purchase their freedom. 68 According<br />

to Patterson, apart from the slaves in Kingston, in order for a<br />

Jamaican plantation slave to purchase his or her freedom, that slave had to<br />

possess a high status among the plantation slaves, he/she had to be a<br />

valuable slave, and receive better treatment from their owner than most of<br />

their fellow slaves. 69 Without a doubt, the elite among the plantation slaves,<br />

would either be the mulattoes or local-born slaves who were skilled artisans<br />

and craftsmen, the domestics in the master’s households, the overseers<br />

of the slave gangs, and those in charge of the plantation workshops. 70<br />

During the late 1820s, just like in the Cape Colony and Jamaica, the<br />

number of Mauritian slaves purchasing their freedom also increased.<br />

Between June 1828 and June 1829, out of 643 slaves who had been<br />

manumitted, 52 or 8% had been freed by will or bequest by their owners.<br />

But even more significant, around 591 slaves or almost 92% had been<br />

manumitted through self-purchase, with the money put up by their relatives,<br />

and through marriages with free coloured individuals. 71 Between<br />

1828 and 1829, when compared with the Cape Colony and Jamaica,<br />

many more Mauritian slaves were buying their freedom, thanks to the<br />

money they saved as well as with the financial help of their families and<br />

friends. Thus, it is evident that the Mauritian slaves, who tried to secure<br />

their manumission, were depending less on the generosity of their owners.<br />

During the late 1820s, this manumission trend was almost a completion of<br />

the process that had started in the early 1820s. 72<br />

Herbert Aptheker, a famous American slave historian, once observed “it<br />

was often possible for the slave, by great perseverance and labor to purchase<br />

his own freedom and, this being accomplished, the freedom of those<br />

dear to him.” Aptheker also described the act of the slave purchasing his<br />

freedom as an individual act of resistance against slavery. 73 Furthermore,<br />

manumission can be seen as “being a passive form of resistance” because<br />

“the slaves sought not to abolish slavery but to ameliorate conditions for<br />

themselves by freeing themselves”. 74 Thus, the slaves who bought their<br />

freedom clearly showed that they rejected their inferior status vis-à-vis<br />

their owners and they wanted to improve their lives as free individuals in<br />

colonial society. 75 Without a doubt, the process of manumission was “the<br />

most profound event in a slave’s life”, but this was a special event which<br />

was experienced by only a few fortunate slaves. 76 Manumission was an<br />

“extremely profound and dramatic act” because it was “a judicial act in<br />

which the property rights in the slave” were surrendered by the<br />

slaveowners and a new status and identity was being created for the<br />

manumittee as a free individual. 77 While referring to the ideas of Friedrich<br />

Hegel, the great German philosopher, on slavery, Orlando Patterson

Historical demography<br />

explains that in the slave’s struggle for freedom and “in his<br />

disenslavement”; he evidently “becomes a new man for himself.” Then,<br />

how does the slave become free and becomes a new man? According to<br />

Hegel, this is achieved “through work and labour” which the slave gradually<br />

realizes and this is truly when the slave’s psychological and physical<br />

journey to freedom begins. 78 Eric Foner points out that one of the<br />

freedoms which the slaves immediately sought was self-ownership. 79<br />

Therefore, by purchasing their freedom with their hard earned cash as<br />

well as with the financial help of their relatives, the manumitted slaves<br />

clearly showed that they asserted “their ownership over their bodies”. In<br />

the process, through their actions, they completely rejected their owners’<br />

claims over them as a piece of property. 80 Indeed, it must have been a<br />

moment of supreme satisfaction for these fortunate slaves, when they were<br />

able to secure their freedom thanks to their own efforts. In addition,<br />

manumission was also a major opportunity for some of these former slaves<br />

to buy the freedom of their enslaved relatives. After all, as it was already<br />

repeatedly emphasized in this chapter, it was extremely common for slaves<br />

to be manumitted by their free coloured relatives and friends. 81<br />

During the late 1820s and early 1830s, many of the slaves who were<br />

manumitted were skilled artisans and craftsmen as well as those who held<br />

a privileged position among the slaves and had access to some type of<br />

financial resources. Furthermore, there is one aspect of manumission in<br />

Mauritius, during the late 1820s, which has hardly been mentioned by<br />

slave historians. 82 In May 1828, the Commissioners of Eastern Inquiry<br />

reported: “We may observe, that the slave artificers and mechanics frequent<br />

the Sunday markets with articles for sale and the production of their<br />

leisure hours,….; indeed we have been assured that many of those<br />

enfranchisements, apparently gratuitous, have in fact been obtained by<br />

purchase from their masters by slaves from the fruit of their own exertions”.<br />

Therefore, many Mauritian slaves who were supposedly freed by<br />

their owners gratuitously had in fact paid for their manumissions them-<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

selves. After all, many of these individuals who had purchased their own<br />

freedom were skilled slaves and they could command high wages or earn<br />

extra money for their precious labour in their free time. 83<br />

In their official letter to Governor Colville, the Franco-Mauritian<br />

slaveowning elite clearly admitted that they were concerned by the fact<br />

that “the commanders, workmen, and servants were generally those who<br />

have the means of purchasing their freedom”. 84 Thus, just like in the<br />

sugar-producing colony of Jamaica, in Mauritius, those who had the best<br />

chance of buying their freedom were the commanders who were put in<br />

charge of the field slaves, those in charge of the estate workshops, the<br />

skilled slaves, and the servants or the domestics. 85 During the late 1820s,<br />

the concern of the Mauritian slaveowners about the skilled slaves purchasing<br />

their freedom was not without reason. Deryck Scarr explains, that ever<br />

since the 1810s and the early 1820s, the slaveowners, who were also the<br />

island’s major sugar planters, were already heavily dependent on the<br />

labour of skilled slaves such as masons, blacksmiths, coopers, joiners, and<br />

locksmiths. 86 It is evident that during the last decade of Mauritian slavery,<br />

“with the expansion of the sugar industry, slave-owners resisted even more<br />

attempts at manumission as they feared an exodus from their estates. In<br />

particular, owners were against compulsory manumission by purchase, i.e,<br />

slaves paying a certain sum for their freedom, because freedom often<br />

would be bought by the most intelligent and hard-working” slaves. Many<br />

female slaves were manumitted through marriage, while the male slaves,<br />

mainly those who were skilled artisans and craftsmen, were able to purchase<br />

their freedom. 87<br />

In 1835, according to the Abstract of District Returns of Slaves in Mauritius<br />

at the time Emancipation, there were 5094 tradesmen or skilled<br />

artisans, 1991 commandeurs or headmen, and 15,556 domestics. When<br />

combined together, there were 22,641 tradesmen, commandeurs, and<br />

domestics. 88 Another estimate was given by Stipendiary Magistrate Percy<br />

Fitzpatrick who reported that out of the 61,121 slaves, there were 6,201<br />

artisans, 1,813 commandeurs, and 15,556 domestics. Fitzpatrick’s report<br />

11

12 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

clearly shows that there were 23,570 domestics, commandeurs, and<br />

skilled artisans. 89 These two important primary sources reveal that the<br />

slaves who had the best chance of buying their freedom consisted between<br />

37.1% and 38.6%, or well over one third, of the island’s slave population.<br />

90<br />

In 1834, Eugene Bernard observed that, between 1827 and 1833, many<br />

of the slaves who had been manumitted were carpenters, blacksmiths, and<br />

masons who earned high wages. He described how a newly freed slave,<br />

who was a good carpenter, had refused a job for which he would have<br />

been paid 30 piastres per month or the equivalent to 30 rix dollars. 91 It is<br />

evident that a skilled slave, like a carpenter, could earn as much as 360<br />

rix dollars for one year. Thus, it may be argued that the slaves who were<br />

skilled artisans and craftsmen were perhaps the most privileged slaves in<br />

the colony because they had the best access to financial resources and to<br />

purchase their freedom. In 1835, there were between 5094 and 6201<br />

skilled slaves and they made up between 8.3 to 10.1 % of the total slave<br />

population. 92 Therefore, the skilled slaves formed a large class within the<br />

Mauritian slave population and apart from securing their freedom, they<br />

could also manumit their enslaved relatives. 93 In 1834, at the Cape of<br />

Good Hope, there were only 1383 skilled slaves who constituted only<br />

3.8% of the slave population. 94 There were roughly 3.8 to 4.5 times more<br />

skilled slaves in Mauritius than at the Cape. By taking into consideration<br />

all these facts, it is not surprising that during the late 1820s and throughout<br />

the 1830s, many more Mauritian slaves and apprentices were able to<br />

purchase their freedom than their Cape counterparts. At the same time, it<br />

is obvious that many of these slaves and apprentices had to make enormous<br />

sacrifices to come up with the money in order to pay for their freedom.<br />

By the sweat of their brow and their inexhaustible perseverance,<br />

they earned their freedom and this fact by itself shows, to what extent,<br />

they were determined to be free. 95<br />

Manumission of Creole and Foreign-Born<br />

Slaves:<br />

A Comparative Perspective<br />

Orlando Patterson explains that in slaveholding societies, throughout<br />

history, there was a greater tendency of manumitting creole or local-born<br />

slaves than foreign slaves or slaves who were imported from abroad. 96 This<br />

situation also existed in the slave societies of Mauritius, the Cape Colony,<br />

and Jamaica during the early nineteenth century. In Mauritius, the creole<br />

slaves had better chances of being manumitted than newly imported<br />

slaves. This fact can clearly be seen in the colony’s manumission<br />

records. 97<br />

Between 1829 and 1830, around 636 slaves were manumitted, 525 or<br />

almost 83% of the manumittees were creole slaves and 111 or over 17%<br />

were foreign-born slaves (See Appendix). 98 In 1830, Baron D’Unienville,<br />

the Chief Archivist of Mauritius, reported that over 33% of the slave<br />

population were creoles and almost 67% were foreign slaves who had<br />

been brought into the colony from Mozambique, Madagascar, India, and<br />

the Seychelles (See Appendix). 99 Interestingly enough, creole slaves<br />

formed over 33% of the slave population, but they consisted almost 83%<br />

of the slaves manumitted between 1829 and 1830. 100<br />

During this one-year period, among the 111 foreign-born slaves who were<br />

freed, around 42 or 37.6% were Indians, 34 or 30.6% were Malagasy,<br />

and 22 or 19.8% were Mozambicans. As for the rest, 10 or 9% were<br />

slaves from the Seychelles and 3 or 2.8% were slaves born in Malaysia<br />

and elsewhere. When compared with the total number of slaves<br />

manumitted in 1829 and 1830, the Indians make up 6.6%, the Malagasy<br />

5.3%, the Mozambicans 3.4%, the slaves from the Seychelles 1.6%, and<br />

the others 0.5%. 101 By 1830, almost 41% of the Mauritian slaves were<br />

Mozambicans, 20% were Malagasy, and almost 6% were Indians. 102<br />

Although the foreign-born slaves made-up almost 67% of the island’s slave<br />

population, they only consisted around 17.4% of the total number of

Historical demography<br />

slaves manumitted between 1829 and 1830. The greatest contrast would<br />

be with the Mozambicans who consisted almost 41% of the slave population,<br />

but they only made up 3.45% of all the slaves manumitted. While<br />

the Indians made up almost 6% of the slave population and they consisted<br />

around 6.6% of all the slaves who were freed. Amazingly enough, there<br />

were six and a half times more Mozambican slaves than Indian slaves in<br />

Mauritius, but the number of Indian slaves manumitted was double that of<br />

the Mozambicans. It highlights the fact that in Mauritius, there was a<br />

greater tendency to manumit Indian slaves, or Asian slaves, than<br />

Mozambican slaves, or African slaves, who were usually field labourers on<br />

the sugar estates. 103<br />

Between 1658 and 1828, at the Cape of Good Hope, creole or local-born<br />

slaves accounted for 70% of all manumitted slaves. Between 1826 and<br />

1834, in Cape Town and the Cape District, local-born slaves made up<br />

80% of the manumitted slaves while the foreign-born slaves around<br />

20%. 104 These figures from the Cape are almost similar with the ones from<br />

Mauritius, for 1829 and 1830, where almost 83% of the slaves freed<br />

were creoles and more than 17% were foreign-born (See Appendix). 105<br />

Just like in Mauritius, in the Cape Colony, there was a greater tendency to<br />

manumit the Asian slaves than the African slaves. 106 George Fredrickson<br />

has shown that between 1715 and 1794, around 290 foreign-born slaves<br />

were manumitted and 275 or almost 95% were Asians and only 15 or just<br />

over 5% were Africans (Mozambicans and Malagasy). 107 Between 1816<br />

and 1834, around 15% of all manumitted slaves were Asians and they<br />

consisted only 10% of Cape Town’s and the Cape District’s slave population.<br />

During this same period, 5% of all the manumitted slaves were<br />

Mozambicans and Malagasy and they made up 20% of the slave population<br />

of Cape Town and the Cape District. 108<br />

It must be remembered that, in Mauritius, only 6.6% of all the<br />

manumitted slaves were Indians and they formed around 6% of the slave<br />

population. At the same time, the East Africans or the Mozambicans and<br />

Malagasy formed almost 61% of the Mauritian slave population, but<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

consisted only 8.7% of all the manumitted slaves. 109 In the Cape Colony,<br />

the white slaveowners did possess a sense of ethnic hierarchy for their<br />

slaves, they saw the Asian slaves as being more intelligent than the African<br />

slaves. Therefore, Asian slaves were usually employed as skilled artisans<br />

and craftsmen. In addition, the slaveowners considered the African slaves<br />

or, to be more precise, the Mozambican slaves to be strong and suitable to<br />

do mostly heavy labour. Therefore, they were usually employed to do the<br />

most difficult and back-breaking work on the wine and the wheat farms of<br />

the south-western Cape. 110 Just like at the Cape of Good Hope, in Mauritius,<br />

there was also a strong correlation between the ethnicity of the slaves<br />

and hard labour. Most of the time, the Indian slaves worked as domestics<br />

and artisans, while the Mozambican slaves were used as agricultural<br />

labourers. The majority of the colony’s Indian slaves were usually employed<br />

to do light work by their owners. But, the overwhelming majority of<br />

the island’s Mozambican slaves, who were located in the colony’s rural<br />

districts, were used to do mostly heavy labour on the sugar estates. 111<br />

Barry Higman indicates that like in many modern slave societies, Jamaican<br />

creole slaves were more frequently manumitted than foreign-born<br />

slaves. 112 Between 1829 and 1832, out of 1362 slaves who were<br />

manumitted, around 126 or 9.3% were foreign slaves who had been<br />

brought mostly from West Africa and 1236 or 90.7% were creole<br />

slaves. 113 Between 1807 and 1832, the number of African-born slaves<br />

dropped from 45% to 25% of the total slave population. Thus, in 1832,<br />

75% of the Jamaican slave population was local-born. 114 Between 1829<br />

and 1832, the stark reality was that foreign-born Jamaican slaves made up<br />

25% of the slave population, but they only accounted for 9.3 % of all<br />

manumitted slaves. At the same time, creole slaves made up 75% of the<br />

slave population and accounted for 90.7% of all manumissions (See<br />

Appendix). 115<br />

When taking a comparative look at the manumission of creole and foreign<br />

slaves in British slave colonies, it is important to look at the level of<br />

creolization. In his comparative article on the slave societies of Mauritius<br />

13

14 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

and the Cape Colony, Nigel Worden explains that the “level of creolisation<br />

in Mauritius was less than that of other slaves colonies, including the<br />

Cape”. 116 In 1826, according to the slave census, around 33.8% of the<br />

rural slaves in Mauritius were local-born while, in Port-Louis, it was only<br />

31%. 117 In 1824, 71% of the slaves of Cape Town and of the Cape District<br />

were local-born and 29% were has been brought from overseas. 118 By<br />

1832, 75% of the Jamaican slave population was local-born and 25% had<br />

been introduced from Africa. 119 Thus, during the mid-1820s and early<br />

1830s, the demographic situation of the Cape Colony and Jamaica was<br />

almost the direct opposite of what was taking place in Mauritius. It is<br />

evident that there was a much higher birth rate in Jamaica and at the Cape<br />

of Good Hope than in British Mauritius. 120 During the 1810s and 1820s,<br />

the Mauritian slave population was unable to naturally reproduce itself, as<br />

a result, large quantities of slaves were brought in to replenish this segment<br />

of the island’s population . 121 This was done largely between 1811<br />

and 1825, through the illegal introduction of thousands of slaves into<br />

Mauritius. 122 The large volume of this illicit slave trade was rather unique<br />

to Mauritius, as a British colony, when compared with Jamaica and the<br />

Cape Colony where the slave trade had been successfully suppressed. 123<br />

As a recapitulation, in Mauritius, between 1829 and 1830, almost 83%<br />

(or around 82.6%) of the slaves manumitted were creoles or local-born<br />

and over 17% (or around 17.4%) were foreign-born (See Appendix). 124<br />

The creole slaves accounted for over 33% of the slave population, while<br />

almost 67% of the slaves came from abroad (See Appendix). 125 These<br />

Mauritian manumission figures are almost similar with Cape Town and the<br />

Cape District, where between 1816 and 1834, around 80% of the<br />

manumittees were local-born slaves and 20% of the slaves had been<br />

brought from overseas (See Appendix). At the same time, over 71% of the<br />

Cape slaves were creoles and their foreign-born counterparts made up<br />

29% of the slave population (See Appendix). 126 By 1832, in Jamaica,<br />

90.7% of all manumitted slaves were local-born and 9.3% were foreignborn<br />

(See Appendix). 127<br />

Furthermore, around 75% of the Jamaican slaves were creoles and 25%<br />

had been imported from overseas (See Appendix). 128 These figures adequately<br />

reinforce the argument that in these three British colonies, creole<br />

slaves stood a much better chance of being manumitted than their foreignborn<br />

counterparts. Furthermore, the foreign-born slaves in Mauritius had<br />

even fewer chances of being manumitted than their peers in the Cape<br />

Colony and Jamaica. But, at the same time, the Mauritian-born slaves also<br />

had better chances of being manumitted than their Cape and Jamaican<br />

counterparts. 129<br />

Urban Manumission in Mauritius, the Cape<br />

Colony, and Jamaica<br />

Orlando Patterson points out that in almost all slave societies, there was a<br />

strong correlation between urban residence and manumission. 130 During<br />

the late 1820s and early 1830s, this fact strongly applies to Port-Louis,<br />

Cape Town, and Kingston. 131 In Mauritius, Jean de la Battie, the local<br />

French consul, reported that between 1825 and 1830, there were 283<br />

manumissions in Port-Louis which contained around 14000 slaves. While,<br />

at the same time, there were only 209 manumissions in the rural districts.<br />

132<br />

During the late 1820s, almost a quarter of the island’s total slave population<br />

was found in Port Louis and 75 per cent of the colony’s slaves were<br />

located in the rural districts, mostly on the sugar estates. 133 At this stage, it<br />

must be pointed out that between 1825 and 1830 roughly around 1,525<br />

slaves were manumitted therefore, the figures provided by de la Battie<br />

only represent less than one third of all the slaves who were freed during<br />

this period. Therefore, his figures might be seen as representing an accurate<br />

sample of the urban and rural slaves who were manumitted during<br />

the second half of the 1820s. 134 De la Battie’s sample indicates that,<br />

during this period, around 57.6% of the slaves who were manumitted<br />

were from Port-Louis and 42.4% were from the rural districts. 135 Furthermore,<br />

between 1835 and 1839, de la Battie estimated that 2,780 appren-

Historical demography<br />

tices were freed, around 1,735 or 62.4% were from Port-Louis and only<br />

1,045 apprentices or 37.6% were from the rural districts. 136 This was also<br />

a sample because it must be remembered that, between 1835 and 1839,<br />

around 9,000 apprentices had bought their freedom. These figures show<br />

that between 1825 and 1839, the number of urban slaves and urban<br />

apprentices being manumitted was increasing, while, at the same time, the<br />

number of rural slaves and rural apprentices being freed was declining.<br />

For the period from 1831 to 1834, at the current stage of this research,<br />

no accurate manumission data has been uncovered for Port-Louis and the<br />

rural districts. But, de la Battie’s figures may give an indication into rural<br />

and urban manumission trend during the early 1830s. At this point, it is<br />

necessary to make an average of the percentage of de la Battie’s figures for<br />

the number of urban and rural slaves who were manumitted from 1825 to<br />

1830 and from 1835 to 1839. This average may give us an idea of the<br />

number of slaves who were freed in Port-Louis and in the rural districts<br />

during the early 1830s. This proposed average yields a figure of 60% for<br />

Port-Louis and 40% for the rural districts. 137 Between 1831 and 1834,<br />

around 3403 slaves were manumitted in the colony. 138 Therefore, during<br />

this four-year period, in Port-Louis, roughly 2,042 slaves were<br />

manumitted, while in the rural districts, around 1361 slaves were freed.<br />

At this stage, the imperative question to be asked is why many more<br />

slaves were manumitted in Port Louis than in the rural districts of Mauritius?<br />

Furthermore, what were the key factors which increased the chances<br />

of the urban slaves to obtain their freedom, through manumission, than<br />

their rural counterparts on the sugar plantations? 139 Frederick Douglass,<br />

the famous ex-slave from the American South, once explained: “A city<br />

slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on the plantation. He is<br />

much better fed and clothed, and enjoys privileges altogether unknown to<br />

the slave on the plantation”. 140 Furthermore, as Orlando Patterson explains,<br />

in many slave societies: “The critical factor at work here was the<br />

fact that the urban areas offered more plentiful opportunities for slaves<br />

either to acquire skills or to exercise some control, if not marginal, over<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

the disposal of their earnings or both”. 141 In 1833, a distinction was made<br />

“in the Abolition Act between praedial field workers and non-praedial<br />

urban and domestic slaves” in all the British slave colonies, with the<br />

exception of St. Lucia. 142 According to the Abstract of District Returns of<br />

Slaves in Mauritius at the time of Emancipation of 1835, there were<br />

around 3237 non-predial head tradesmen and inferior head tradesmen,<br />

929 non-predial slaves, and also thousands of domestics. 143 Without a<br />

doubt, many of these non-praedial slaves were found in Port-Louis and<br />

they formed part of a large urban class of skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled<br />

slaves which continued to exist during the early post-emancipation<br />

period. 144 After all, an 1846 census of the colony shows that in Port-<br />

Louis, there were over 2,816 urban ex-apprentices who were involved in<br />

commerce, trade, and the manufacturing sector. This group of former<br />

apprentices also included hundreds of carpenters, carters, wheelwrights,<br />

tailors, masons, seamstresses, and bakers. 145<br />

In 1846, in his report on the ex-apprentices in Port-Louis, Stipendiary<br />

Magistrate Fitzpatrick pointed out that there was a large and thriving class<br />

of urban of ex-apprentices and many among them were skilled artisans<br />

and craftsmen. The other former apprentices who formed part of this<br />

urban underclass were cooks, grooms, sailors, boatmen, shopkeepers,<br />

traders, hawkers, domestics, and seamstresses. The majority of among<br />

these ex-apprentices had either lived for many years or had spent most of<br />

their lives in Port Louis. In addition, they continued doing the same work<br />

that they did as urban slaves and they even taught their trade to their<br />

children. During the early 1830s, many of these urban slaves, especially<br />

the skilled artisans and craftsmen, were able to earn high wages and were<br />

financially better off than most of the rural slaves. 146 Thus, what can be<br />

concluded is that during the late 1820s and early 1830s, a large class of<br />

skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled urban slaves had emerged in Port-<br />

Louis. Furthermore, these urban slaves, especially the skilled ones, had<br />

access to financial resources and, as a result, they had the best chance of<br />

purchasing their freedom. 147<br />

15

16 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

While discussing the issue of manumission in Kingston in 1832, Barry<br />

Higman explains that “those slaves who purchased their own freedom<br />

were predominantly black town-dwellers, because the nature of their<br />

occupations and their relative independence enabled them to acquire<br />

cash, and because the urban skilled slave saw more to be gained from<br />

freedom than did his rural counterpart”. 148 This evidently explains why<br />

during the late 1820s and the early 1830s, many more slaves were able<br />

to secure their manumission in Port Louis, Cape Town, and Kingston than<br />

in the rural districts. 149 Therefore, during the last years of slavery in<br />

Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica, manumission was mainly “an<br />

urban phenomenon”. 150<br />

During the 1830s, in Port-Louis, according to a police report, there were<br />

many slaves/apprentices who were dealers in contraband goods. 151 During<br />

this period, through gambling alone, around 20,000 rix dollars changed<br />

hands every day among the urban slaves/apprentices and they were also<br />

responsible for the increase of burglary in Port Louis. 152 Through these<br />

illegal activities, the urban slaves/apprentices had access to large sums of<br />

money and, like the skilled urban slaves, they had a better chance of<br />

buying their freedom than most of their rural counterparts.<br />

When compared with the Cape Colony and Jamaica, there was a greater<br />

concentration of urban slaves in Mauritius. 153 In 1831, Port-Louis contained<br />

around 16,139 or 25.5% of the colony’s slaves and three years<br />

later, this figure would fall to 15,412 or 24%, with 48,919 or 76% of the<br />

slaves residing in the rural areas. 154 By 1834, at the Cape, 5583 or<br />

15.4% of the slaves lived in Cape Town and 30,586 or almost 84.6% of<br />

them lived in the rural districts. 155 Between 1829 and 1832, around<br />

12,896 or 4% of all the Jamaican slaves lived in Kingston and 309,525<br />

or 96% of them resided mostly in the rural parishes. 156<br />

As a recapitulation, in 1834, around 60% of the Mauritius slaves who<br />

were manumitted lived in Port-Louis, where 24% of the colony’s slave<br />

population was found. 157 During that same year, around 90% of the<br />

manumissions took place in Cape Town and by then, only 15.4% of the<br />

colony’s slave population lived there. 158 In 1832, roughly 22% of the<br />

manumissions in Jamaica took place in Kingston where 4% of that island’s<br />

slave population resided. 159 These figures show that the slaves of Cape<br />

Town stood the best chance of being manumitted than their counterparts<br />

in Port-Louis and Kingston. 160<br />

The Manumission of Female and Male Slaves:<br />

A Comparative Perspective<br />

The sexual identity of a slave was an extremely important factor which<br />

heavily influenced a slave’s access to freedom. 161 Robert Shell once noted<br />

that “the process of manumission favored adult female slaves and their<br />

children” which was common in many slave societies. 162 In Mauritius, the<br />

Cape Colony, and Jamaica, most often those who were manumitted were<br />

young female slaves. 163<br />

Between 1768 and 1789, in Mauritius, out of 785 manumitted slaves,<br />

around 479 or 61% were females and 306 or 39% were males. 164 The<br />

result of having so many females being manumitted is that it caused a<br />

great imbalance in the sex ratio in the colony’s free population of colour.<br />

In 1788, among the free coloureds, there were 725 females and only 435<br />

males. By 1806, the free coloured females outnumbered the males by two<br />

to one in the colony and three to one in Port-Louis. 165 This unhealthy<br />

demographic trend continued well into the early nineteenth century. 166<br />

Between 1821 and 1826, around 433 slaves were manumitted and<br />

65.6% were females and 34.4% were males. 167 Between 1829 and 1830,<br />

out of 612 slaves who were manumitted, around 45% were males and<br />

55% were females. 168 Between 1826 and 1832, female slaves consisted<br />

38% to 39% of the slave population when compared with 62% to 61% for<br />

their male counterparts. 169 It is evident that, in Mauritius, the percentage<br />

for the manumission of female slaves remained almost the same between<br />

1768 and 1825. But after 1829, the gap in the number of manumissions<br />

between the male and female slaves was gradually narrowing. 170

Historical demography<br />

At the Cape of Good Hope, the slaveowners manumitted their female<br />

slaves more frequently than their male slaves. Between 1816 and 1824,<br />

out of 266 slaves who were manumitted, 44.7% were males and 55.3%<br />

were females. 171 From the end of the slave trade in 1808 until 1834,<br />

55% of the manumitted slaves in the colony were females. 172 Between<br />

1816 and 1834, in Cape Town, the Cape District, and Stellenbosch<br />

district, female slaves consisted just over 40% of the slave population,<br />

while for the male slaves it was 60%. 173<br />

From 1826 to 1829, in Jamaica, out of 1,117 slaves who were<br />

manumitted, around 67.6% were females and 32.4% were males. But<br />

between 1826 and 1832, this difference in the number of manumissions<br />

between male and females slaves began to narrow. During this six-year<br />

period, 1,362 slaves were freed, around 41% were males and 59% were<br />

females. This phenomenon was largely due to the fact that, the number of<br />

male slaves being manumitted between 1829 and 1832, when compared<br />

with the period between 1826 and 1829, increased from 362 to 558. 174 It<br />

must be remembered that between 1829 and 1830, 45% of the slaves<br />

who were freed were males and 55% were females. 175 In 1826 and 1832,<br />

female slaves consisted 38% to 39% of the total slave population when<br />

compared with 62% to 61% for the male slaves. 176 Therefore, during this<br />

period, the situation in Mauritius was almost similar to the one in Jamaica,<br />

in terms of the percentage of male and female manumissions. 177<br />

In 1826 and 1832, in contrast with Mauritius and the Cape Colony, there<br />

were more female than male slaves in Jamaica. In 1826, the females<br />

made up 50.8% of the Jamaican slave population while the males consisted<br />

only around 49.2%. Six years later, this gap increased slightly to<br />

51.4% for the female slaves and 48.6% for their male counterparts. This<br />

was a demographic feature which Jamaica shared with other British Caribbean<br />

slave colonies like Dominica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Grenada. 178<br />

During the early 1830s, in Mauritius and Jamaica, with the exception of<br />

the Cape Colony, the gap in the number of male and female slaves who<br />

Gauging the Pulse of Freedom<br />

were being manumitted was gradually narrowing. But, when compared<br />

with Mauritius and the Cape of Good Hope, Jamaica had many more<br />

female than male slaves. 179<br />

In Mauritius, Jean de la Battie observed that during the late 1820s and<br />

throughout the 1830s, those who were generally manumitted were young<br />

women and their children. 180 According to the manumission records of the<br />

Protector of Slaves, between 1829 and 1831, more than 70% of those<br />

who were freed were women and children. In addition, between 1829 and<br />

1830, around 500 domestics were manumitted or 40% of all the slaves<br />

who were freed. 181<br />

In 1834, in the Western Cape, many of the female slaves were employed<br />

as domestics who worked and lived in the households of their owners.<br />

Therefore, they were close to the families of their owners in terms of<br />

physical proximity and emotional ties. 182 Between December 1834 and<br />

December 1835, 73 apprentices were freed in Cape Town and among<br />

them 47 were females. These urban female apprentices were freed thanks<br />

to the money put up by their families and, in some cases, even by those<br />

who had hired them from their owners. In addition, a few of these Cape<br />

Town female apprentices were also manumitted gratuitously by their<br />

owners. 183 But, during the apprenticeship period, the manumission of the<br />

female apprentices did not only take place in Cape Town because some<br />

were also freed in the country districts of the Western Cape, like Worcester.<br />

184<br />

Conclusion<br />

This paper has tried to show that through manumission, the Mauritian,<br />

Cape, and Jamaican slaves sought to ameliorate their lives, regain their<br />

human dignity, and create a new identity for themselves as free individuals<br />

and free citizens within colonial society. Between the 1810s and early<br />

1830s, in these three colonies, thousands of slaves were able to obtain<br />

their freedom before the abolition of British colonial slavery. However, it<br />

must be remembered that manumission was obtained only by a small<br />

17

18 Satyendra Peerthum<br />

<strong>Session</strong> 3 (b)<br />

number of fortunate slaves, because the majority of the slaves in these<br />

three British colonies remained under the shackles of forced servitude<br />

until the advent of final emancipation in the late 1830s. Between the<br />

1810s and early 1830s, the manumission of these slaves made a major<br />

contribution to the rapid increase in the number of the free coloureds in<br />

Mauritius, the Cape Colony, mainly in Cape Town, and Jamaica.<br />

During the second half of the 1820s, British slave amelioration laws,<br />

dealing with manumission and in setting up the Office of the Protector of<br />

Slaves, were introduced in Mauritius, at the Cape of Good Hope, and<br />

Jamaica. These slave reform laws swept away the old manumission laws,<br />

liberalized the manumission process for the slaves, and encouraged their<br />

manumission. These slave amelioration measures were introduced at the<br />

Cape of Good Hope, through Ordinance No.19 of 1826, in Mauritius,<br />

through Ordinance No.43 of 1829, and in Jamaica, a similar law was<br />

passed in 1826. During the last years of British colonial slavery, the<br />

introduction of these liberal laws got rid of the costly fees and complex<br />

procedures of the old colonial manumission laws. These new legal measures<br />

allowed the slaves to purchase their freedom and made it easier for<br />

free coloured individuals to manumit their slave relatives. During the late<br />

1820s and early 1830s, there was a sharp decrease in the number of<br />

slaves being manumitted by the slaveowners and a dramatic increase in<br />

the number of slaves purchasing their freedom. During this period, many<br />

Mauritian, Cape, and Jamaican slaves were purchasing their freedom,<br />

thanks to the money they were saving as well as with the financial help of<br />

their free coloured families and friends. Therefore, it was evident that the<br />

slaves, who tried to secure their manumission, were depending more on<br />

their own financial resources and less on the generosity of their owners.<br />

It is extremely important to point out that between the 1810s and early<br />

1830s, the manumission of many Mauritian, Cape, and Jamaican slaves<br />

was made possible largely through their social relationships and contacts<br />

with the free coloureds. The manumission records of Mauritius and the<br />

Cape Colony clearly show that free coloured men bought the freedom of<br />

their concubine, free coloured women manumitted their lovers, and free<br />

coloured men and women freed their parents and children. After being<br />

manumitted, many of these ex-slaves legitimized their relationship by<br />

getting married, they formed families, and started a new life as free individuals<br />

in colonial society. In addition, the Mauritian manumission records<br />

of the 1810s and 1820s highlighted the fact that some of the manumitted<br />

slaves in that British colony were no longer natally alienated, dishonoured,<br />

and socially dead beings. During this period, some of these fortunate<br />

Mauritian slaves (or manumittees) were able to get married, have children,<br />

acquired land, and they were even able to return to settle in their native<br />

land. In general, it was mainly the former Malagasy slaves and their<br />

relatives who left Mauritius to return to the country of their origin.<br />

The liberalization of the manumission process led to a massive increase in<br />

the number of slaves who were being freed as well as in the manumission<br />

rates of Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica. During the late 1820s<br />

and early 1830s, when compared with the first half of the 1820s, the<br />

Mauritian manumission rate increased by six fold, at the Cape of Good<br />

Hope, it almost tripled, and in Jamaica, it rose by more than 26%. Furthermore,<br />

between 1829 and 1834, Mauritius had an unusually high<br />

manumission rate as a British colony. In 1832, 1,647 slaves were freed,<br />

the greatest number of slaves to be manumitted, in one year, during the<br />

entire period that slavery existed in the island. This contrasts with the<br />

Cape’s highest manumission figure for one year, in 1827, when 245<br />

slaves were freed. The figure for the Cape Colony is almost seven times<br />

lower than the highest Mauritian manumission figure for one year. In<br />

Jamaica, the greatest number of slaves were manumitted between 1826<br />

and 1829, when around 1117 slaves were freed, which represents an<br />

annual average of 372. The highest manumission figure for Jamaica for<br />

one year was four and a half times lower than the highest Mauritian<br />

manumission figure for one year.

Historical demography<br />

It is evident that between 1829 and 1834, Mauritius had a much higher<br />

manumission rate which meant that many more slaves were being freed,<br />

when compared with the Cape Colony and Jamaica. These figures also<br />

indicate that the Mauritian slaves had greater access to freedom, through<br />

manumission, and many more slaves were becoming members of the<br />

island’s free coloured community than their Cape and Jamaican counterparts.<br />

These facts clearly reinforce the argument that, during last years of<br />

British colonial slavery, to a certain extent, Mauritius had an open slave<br />

society. In addition, during this period, the British slave amelioration<br />

legislation, dealing with manumission, had a much greater impact in<br />

Mauritius than at the Cape of Good Hope and in Jamaica. Furthermore,<br />

between 1835 and 1839, many more Mauritian apprentices were able to<br />

purchase their freedom than the Cape and Jamaican apprentices. After all,<br />

it must be remembered that, between 1829 and 1839, the Mauritian<br />

slaves and apprentices possessed “a frenzy for freedom” because they<br />

were determined to be free. Without doubt, quantitative manumission<br />

clearly shows that the introduction of British amelioration legislation, which<br />

liberalized the manumission laws in Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and<br />

Jamaica, greatly facilitated the access of the slaves to freedom and it lead<br />

to a sharp increase in the manumission rates.<br />

In Mauritius, the Cape Colony, and Jamaica, creole slaves stood a much<br />

better chance of being manumitted than the foreign-born slaves. During<br />

this period, in Mauritius, the foreign-born slaves greatly outnumbered<br />

their local-born counterparts, while at the Cape of Good Hope and Jamaica,<br />