Jasper Finke, Crisis and Law - New York University School of Law

Jasper Finke, Crisis and Law - New York University School of Law

Jasper Finke, Crisis and Law - New York University School of Law

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

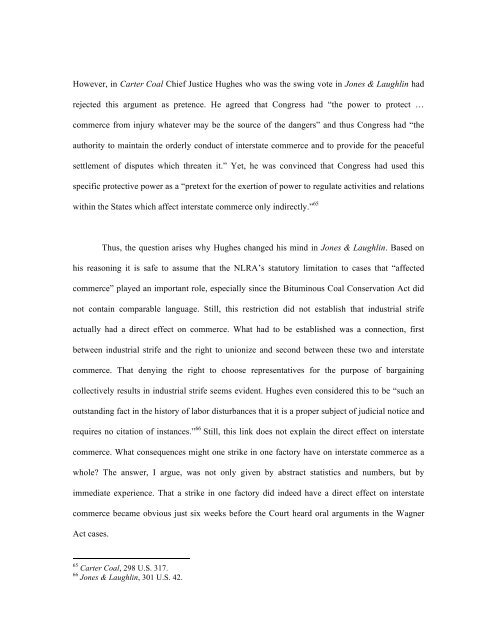

However, in Carter Coal Chief Justice Hughes who was the swing vote in Jones & Laughlin had<br />

rejected this argument as pretence. He agreed that Congress had “the power to protect …<br />

commerce from injury whatever may be the source <strong>of</strong> the dangers” <strong>and</strong> thus Congress had “the<br />

authority to maintain the orderly conduct <strong>of</strong> interstate commerce <strong>and</strong> to provide for the peaceful<br />

settlement <strong>of</strong> disputes which threaten it.” Yet, he was convinced that Congress had used this<br />

specific protective power as a “pretext for the exertion <strong>of</strong> power to regulate activities <strong>and</strong> relations<br />

within the States which affect interstate commerce only indirectly.” 65<br />

Thus, the question arises why Hughes changed his mind in Jones & Laughlin. Based on<br />

his reasoning it is safe to assume that the NLRA’s statutory limitation to cases that “affected<br />

commerce” played an important role, especially since the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act did<br />

not contain comparable language. Still, this restriction did not establish that industrial strife<br />

actually had a direct effect on commerce. What had to be established was a connection, first<br />

between industrial strife <strong>and</strong> the right to unionize <strong>and</strong> second between these two <strong>and</strong> interstate<br />

commerce. That denying the right to choose representatives for the purpose <strong>of</strong> bargaining<br />

collectively results in industrial strife seems evident. Hughes even considered this to be “such an<br />

outst<strong>and</strong>ing fact in the history <strong>of</strong> labor disturbances that it is a proper subject <strong>of</strong> judicial notice <strong>and</strong><br />

requires no citation <strong>of</strong> instances.” 66 Still, this link does not explain the direct effect on interstate<br />

commerce. What consequences might one strike in one factory have on interstate commerce as a<br />

whole? The answer, I argue, was not only given by abstract statistics <strong>and</strong> numbers, but by<br />

immediate experience. That a strike in one factory did indeed have a direct effect on interstate<br />

commerce became obvious just six weeks before the Court heard oral arguments in the Wagner<br />

Act cases.<br />

65 Carter Coal, 298 U.S. 317.<br />

66 Jones & Laughlin, 301 U.S. 42.