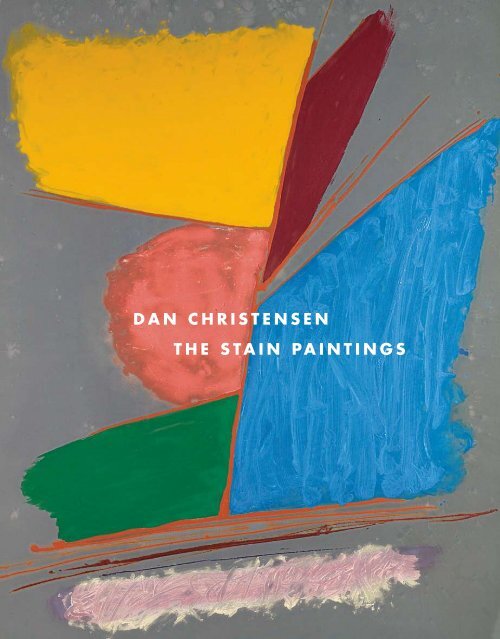

Dan Christensen: The Stain Paintings - Spanierman Modern

Dan Christensen: The Stain Paintings - Spanierman Modern

Dan Christensen: The Stain Paintings - Spanierman Modern

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

d A n c h r i s t e n s e n<br />

the stAin pAintings<br />

A

dAn christensen<br />

the stAin pAintings, 1976–1988<br />

LisA n. peters<br />

feBruAry 8 to mArch 12, 2011<br />

spAniermAn modern<br />

53 eAst 58th street new york, ny 10022-1617 teL (212) 832-1400<br />

christineBerry@spAniermAn.com www.spAniermAnmodern.com<br />

1

Among coLor fieLd painters, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

(1942–2007) is best known for his pioneering<br />

use of the spray gun and the window-washing<br />

squeegee, from which he produced innovative and<br />

dynamic works with lustrous surface qualities. 1<br />

Less attention has been given to the paintings he<br />

created from 1976 to 1988, in which the staining<br />

of the canvas played a central role. As in his<br />

other works, in these images, <strong>Christensen</strong> explored<br />

many facets in the nature of painting, addressing<br />

issues he had considered earlier, while moving into<br />

new territory. Encompassing wide-ranging and<br />

innovative techniques, these color-soaked paintings,<br />

with their skeletal, skittish calligraphic lines<br />

and unusual harmonies of shape and tone, exude<br />

the artist’s pleasure and passion in the act of painting<br />

during a particularly joyous time in his life.<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong>’s usage of staining came about as a<br />

natural step in his logical progression, as he sought<br />

new ways to pursue the issues that compelled him.<br />

A similar development had occurred in his “plaid”<br />

paintings. 2 In these works of 1969–71, he turned<br />

from the spray gun to the use of commercial<br />

paint rollers and window-washing squeegees that<br />

he pulled or pushed across unstretched canvases<br />

that were stapled to a carpeted Xoor. Yet despite<br />

this new method and the contrast in appearance<br />

between the airy and luminous sprays and the<br />

tighter, more solid plaids, <strong>Christensen</strong> did not see<br />

a “drastic” change in his art. “<strong>The</strong> main diVerence,”<br />

he told the New York Times reporter Grace<br />

Glueck in 1971, “is that I’m working with more<br />

surface. I couldn’t get enough paint onto the<br />

canvas by spraying, or at least not the kind of paint<br />

I wanted.” 3<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong>’s turn to staining had a comparable<br />

genesis. <strong>The</strong> plaids had been followed by the<br />

white and dark “slab” paintings, some squeegeed<br />

or spread with masonry trowels, and others created<br />

with thick brushstrokes swirled into tactile<br />

layers of pigment, works in which <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

took advantage of new developments in acrylic<br />

paints that extended and thickened pigments.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se dense, manipulated, scraped surfaces seem<br />

the antithesis of the “stains,” in which paint and<br />

canvas are wedded, the canvas weave is part of the<br />

image, and colored shapes and lines seem to lithely<br />

graze the surface. Yet, in the artist’s exploration of<br />

the surface as a Weld for ongoing painting activity,<br />

this movement from thick to thinly bled pigment<br />

is less dramatic than it might appear from a visual<br />

comparison of the two groups of works. <strong>The</strong> paint<br />

extending agents <strong>Christensen</strong> employed in the<br />

slabs may have prompted him to consider and<br />

want to explore the opposite, the additives that<br />

could produce the eVect of dilution. Thus, rather<br />

than a reversal, the slab and stain paintings may<br />

be seen as two sides of the same coin.<br />

In fact, one link between these two groups is<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong>’s fascination with the possibilities of<br />

the new paints and painting products that came<br />

on the market, beginning in the 1960s. Whereas<br />

the Abstract Expressionists of an earlier generation<br />

had worked in oils thinned with turpentine, the<br />

younger generation had access to the new waterbased<br />

acrylics developed by Leonard Bocour and<br />

Sam Golden. <strong>The</strong>se included latex house paints<br />

and paints that could be thinned with water to the<br />

consistency of a watercolor wash without losing<br />

their color. <strong>The</strong> new paints spread easily, dried<br />

quickly, and left clean edges, by contrast with<br />

the blurring effects of thinned oils. Among the<br />

additives that <strong>Christensen</strong> favored was a tensionbreaker<br />

developed by Golden. A substance with<br />

the property of liquid detergent but without its<br />

viscosity, the tension breaker could be added to a<br />

water-based paint to reduce surface tension, allowing<br />

paint to disperse readily and penetrate into the<br />

canvas rather than laying on top of it. Unavailable<br />

when Helen Frankenthaler began to use staining<br />

methods in the early 1950s, this means of achieving<br />

liquidity was clearly one that <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

found rich in opportunities that he avidly pursued.<br />

As he had in the plaids, in the stains, <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

3

4<br />

Fig. 1.<br />

<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>, Studio,<br />

Waverly Place, New York,<br />

1981; photograph by<br />

Arthur Mones (1919–1998),<br />

Collection of the <strong>Dan</strong><br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> Marital Trust.<br />

began a work by stapling the unstretched canvas<br />

to the carpeted Xoor. Mixing his colors in cups<br />

or buckets, he would then pour the thinned paint<br />

onto the raw canvas and roll the paint uniformly<br />

to create an overall ground for the painting. He<br />

would sometimes lay multiple colors on top of<br />

each other to achieve the desired hue. <strong>The</strong> next<br />

step was the calligraphic “drawing,” or framework,<br />

of the piece. A stick, a brush, sometimes a turkey<br />

baster, would be the instrument of choice for this<br />

aspect of the painting. He would Wnish by pouring<br />

paint into areas around this framework where he<br />

wanted color, and he would then manipulate it<br />

with paint rollers, brushes, or basters. At times he<br />

left the color on the surface and at other times he<br />

let it bleed into the canvas. In a few instances, he<br />

would go over an area with a Wne gritted sandpaper<br />

to give a painting a textured look.<br />

While reXecting issues that would occupy<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> throughout his career, the paintings<br />

in this show represent a unique convergence in<br />

his art, as he merged the Xatness that was a staple<br />

of Color Field painting with the tactility and gestural<br />

presence of action that had been a foundation<br />

of Abstract Expressionist painting. Although<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> had been too young to take part in<br />

the Abstract Expressionist movement during its<br />

heyday, having moved to New York in 1965, he<br />

had absorbed a knowledge of the movement in his<br />

youth. When he was sixteen, he saw the work of<br />

Jackson Pollock on a trip to Denver, an experience<br />

that made him realize that “he could take<br />

a diVerent approach to art—that it was possible<br />

for painting to be a personal experience.” 4 His<br />

absorption of the art of his predecessors was noted<br />

by Valentin Tatransky in 1982. Reviewing a show<br />

consisting primarily of <strong>Christensen</strong>’s stains being<br />

held at Meredith Long Contemporary Gallery<br />

in New York, Tatransky acknowledged this early<br />

exposure, writing: “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong> is a painter<br />

who’s thought hard about Pollock, Newman,<br />

Olitski, and Noland, going through them rather<br />

than around them.” Referencing the paintings on<br />

view, Tatransky observed: “Other artists have also<br />

tried to break the pictorial canon of high abstract<br />

art in this way, and many of their results have<br />

been poor. What makes <strong>Christensen</strong> succeed is his<br />

sensitivity for surface. He’s especially good at laying<br />

down and layering washes of color, and so his fragile,<br />

brittle, tree-like images come as a surprise.” 5<br />

Despite the continuity in <strong>Christensen</strong>’s art from<br />

the slabs to the stains, one immediate diVerence<br />

is the emergence in his art of “Wgure-ground”<br />

relationships that he had previously suppressed.<br />

Yet, that this new “imagery” did not compromise<br />

the “cohesive eVect of all-overness,” was noted<br />

by John ElderWeld in the catalogue for New Work<br />

on Paper 1, a show he curated for the Museum of<br />

<strong>Modern</strong> Art in 1981, shortly after his arrival as<br />

chief curator at the museum. Among the eight<br />

artists included in the exhibition, <strong>Christensen</strong> was<br />

represented by eleven works in acrylic on paper<br />

that were similar to his stain paintings on canvas<br />

of the time. To ElderWeld, <strong>Christensen</strong> had kept<br />

the eVect uniWed because “the drawing that makes<br />

each picture frankly repeats the geometry of the<br />

whole surface—following its corners, its diagonals,

or dividing it down the center—as well as displacing<br />

that geometry at the same time.” ElderWeld<br />

observed the way that the color of <strong>Christensen</strong>’s<br />

drawing either stayed “quite close in tone to that<br />

of the ground or is a thin or whitened or otherwise<br />

‘light’ form of drawing that does not seem to<br />

cut into depth . . . because the drawing either lays<br />

candidly on top of the Xat surface (which seems,<br />

therefore, to pass uninterruptedly beneath it) or is<br />

embedded against the surface by accents and areas<br />

of color that form, as it were, an upper or overlayed<br />

surface.” In a review of the exhibition, Hilton<br />

Kramer also commended <strong>Christensen</strong>’s drawings,<br />

remarking how, for example, “a watercolor shape<br />

is made to ‘rhyme,’ so to speak, with a crayon line<br />

of similar color or hue.” 6 In a Newsweek article, in<br />

which he covered the show, John Ashbery noted<br />

that <strong>Christensen</strong>’s “lighter-than-air abstractions”<br />

evoked “tendrils held up to the light.” 7<br />

In the Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art’s catalogue<br />

ElderWeld gave credence to how the giving and<br />

taking of space across <strong>Christensen</strong>’s surfaces,<br />

whether frontal or open, gave his art coherence<br />

and stability. At the same time, ElderWeld observed<br />

that <strong>Christensen</strong>’s new work suggested certain<br />

organic allusions, writing: “Its very creation of<br />

geometry from gesture invites comparison with<br />

spontaneous natural growth, just as the particular<br />

structures thus formed invite comparison with<br />

speciWc fragments and forms of the natural world.”<br />

While recognizing that abstract art naturally<br />

“makes concessions to the appearance of things<br />

outside of itself,” ElderWeld noted that the associations<br />

to be drawn from <strong>Christensen</strong>’s works<br />

gave them their distinctive moods, which he felt<br />

were often pastoral, “telling of the instinctual, of<br />

the fragile as well as lush beauty, and above all of<br />

sensual delectation.” 8 Of the works <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

created between 1976 and 1984, the art historian<br />

James Monte also commented on the associative<br />

aspect of these paintings, stating: “A shaping of<br />

thickly painted color turns into a fantastic creature,<br />

in one instance a goggle-eyed amphibian<br />

emerging from a luminously painted ground.” 9<br />

At one point Monte even referred to these paintings<br />

as biomorphic abstractions, evoking the legacy<br />

of art of Joan Miró, for which <strong>Christensen</strong> had<br />

a deep reverence. 10 That <strong>Christensen</strong>’s new works<br />

struck the nerve of his time was reXected in the<br />

commission he received from Delmar Hendricks,<br />

the director of the Gallery at Lincoln Center and<br />

the head of its poster program, to create a poster<br />

for the Mostly Mozart Festival of 1980. <strong>Christensen</strong>’s<br />

serigraph, portraying minimal washes of color and<br />

line, was the Wrst, and possibly the only special<br />

edition print to sell out (Fig. 2).<br />

Although it may be a stretch to link the works<br />

of 1976 to 1987 directly with <strong>Christensen</strong>’s life,<br />

the years he created them encompass a period of<br />

particular happiness for him. Settled in New York,<br />

his divorce of the late 1960s behind him, in 1978,<br />

he married the actor and model Elaine Grove<br />

(now a sculptor). <strong>The</strong>ir son, Jimmy, was born in<br />

1979, and a second son, Willie, arrived in 1982.<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong>’s son from his Wrst marriage, Moses, a<br />

teenager then, was present for summer visits. <strong>The</strong><br />

period was one in which the family spent summers<br />

in the Springs, Long Island, near the homes<br />

of many like-minded abstract painters, enjoying<br />

a place to which they would move permanently<br />

in 2002. Among the artists who regularly came by<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong>’s studio in those days were the painters<br />

Larry Poons, Larry Zox, and Ronnie LandWeld,<br />

and the sculptors Michael Steiner and Peter<br />

Reginato. Jack Bush, Daryl Hughto, and Walter<br />

Fig. 2.<br />

Fine Arts Creations, Inc.,<br />

New York, poster after serigraph<br />

by <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

for Mostly Mozart Festival,<br />

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln<br />

Center, July 14–August 23,<br />

1980, Collection of the <strong>Dan</strong><br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> Marital Trust.<br />

5

6<br />

Fig. 3.<br />

<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong> in<br />

chest waders, Montauk,<br />

New York; photograph by<br />

Elaine Grove, Collection<br />

of the <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

Marital Trust.<br />

Darby Bannard lived out of town, but would visit<br />

when they came to the city. At Max’s Kansas City,<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> would see and spend time with Jules<br />

Olitski and Kenneth Noland. Times of friendship,<br />

these gatherings also provided opportunities<br />

for a spirited exchange of ideas that spurred the<br />

artists to venture in new directions in their work.<br />

<strong>The</strong> poet Billy Collins and the art historian Karen<br />

Wilkin also were in touch with <strong>Christensen</strong>, as<br />

was the noted critic Clement Greenberg, who had<br />

championed Post-Painterly Abstraction beginning<br />

in the early 1960s. 11 An admirer of <strong>Christensen</strong>’s<br />

work, Greenberg stated in 1990: “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

is one of the painters on whom the course of<br />

American art depends.” 12 Yet, as Grove recalls,<br />

“<strong>Dan</strong> liked Clem very much and had enormous<br />

respect for his eye, but he did not consider himself<br />

a strict Greenbergian formalist.”<br />

Despite the abstractness of <strong>Christensen</strong>’s art, his<br />

Long Island summers are suggested in many of<br />

the stains. While Atlantic Champagne (1979) evokes<br />

the frothiness of the drink in its title, it also references<br />

the sea, where <strong>Christensen</strong> spent time surf<br />

casting at the ocean’s edge. In other images such<br />

as Troubadour (1988), Sissystrut (1980), and Santali<br />

(1980), sails, Xags Xying, sea breezes, and coastal<br />

light seem to preside. <strong>Christensen</strong>’s enigmatic<br />

titles reference a number of sources. However, the<br />

artist would not be thinking of a literal title as he<br />

painted. Instead a title often simply occurred to<br />

him when he stood back from a completed work,<br />

or some aspect of a work would bring a title to<br />

mind. To express the idea of a separation between<br />

a title and a work, <strong>Christensen</strong> would at times<br />

slightly change the spelling of a word used in a<br />

title. <strong>The</strong> titles of <strong>Christensen</strong>’s paintings are best<br />

considered as reXective of his context, conveying<br />

the music he played in his studio or names from<br />

literature or Wlm that had drawn his attention. <strong>The</strong><br />

titles of works in the show include Beulah Land<br />

(1978), perhaps referencing the hymn of this name<br />

written in 1875 by Edgar Page Stiles, or an idyllic<br />

place looking over a heavenly vista as described in<br />

John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. <strong>The</strong> title Sissystrut<br />

(1980) is drawn from the funk classic “Cissy Strut,”<br />

by the Meters, a New Orleans Band that launched<br />

the career of Art Neville. Jambo Caribe (1981) is<br />

the name of a 1964 song by Dizzy Gillespie, while<br />

Topsy Part II is the title of an R&B hit by Cozy<br />

Cole, famed for its prolonged drum solo. Song of<br />

Ceylon (1977) may reference the unusual 1934<br />

British documentary by John Grierson about<br />

native rituals in Sri Lanka.<br />

A number of works suggest <strong>Christensen</strong>’s<br />

response to the legacy of Abstract Expressionism.<br />

In Atlantic Champagne (1979), <strong>Christensen</strong> Xung,<br />

brushed, and pulled Pollock-like gestures of<br />

white paint of diVerent consistencies on a wallscale<br />

horizontal, but the cartoonish humor and<br />

scribbling suggests a pure pleasure in the movement<br />

of paint on this expanse rather than a sense<br />

of angst. A feeling of the light in Monet’s last<br />

paintings reverberates outward from this work.<br />

Monet, in fact, is an artist for which <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

felt a particular aYnity, while paintings in which<br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> created harmonies with vivid hues<br />

and a balance of asymmetrical forms such as Troubadour<br />

(1988) bring to mind his admiration for the<br />

art of Matisse, who <strong>Christensen</strong> noted as among<br />

his favorite artists in 1974. 13 In the shimmering<br />

Ridge (1976), <strong>Christensen</strong> poured silver under the<br />

semi-translucent white ridged backbone, bringing<br />

the light through from the back of this form.

It was works such as this to which the poet and<br />

critic John Ashbery referred in a review of an<br />

exhibition of <strong>Christensen</strong>’s art in 1979. In a day<br />

when artists had either taken the Minimal into the<br />

purely conceptual or had returned to representational<br />

forms of image-making, Ashbery found it<br />

“sobering and refreshing to turn to a number of<br />

artists who are extending the language of modernism<br />

in a more traditional and serious way.” He<br />

went on to note that “one younger artist who has<br />

renewed the tradition [of Color Field painting]<br />

honorably is <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>. His pale, vaporous<br />

washes of light are delectable. Often they are<br />

loosely organized along a white line which serves<br />

as an axis for vague blotches of color to relate to—<br />

sometimes like petals on a stem, or laundry on a<br />

clothesline, or clouds bisected by a telephone wire,<br />

though such comparisons are considered odious<br />

in discussions of this kind of work.” Ashbery<br />

found <strong>Christensen</strong>’s color occasionally “smoldering<br />

and sensuous,” but observed that the artist<br />

was “mainly interested in articulating the nuances<br />

separating patches of close-keyed dull pastel tones,<br />

and he does it masterfully. He forces the eye to<br />

recognize distinctions among areas of color which<br />

at Wrst have strong family resemblances and only<br />

somewhat later turn out to be mavericks who<br />

could just as easily be at odds with each other.”<br />

Referencing the universal metaphor of the Tree<br />

of Life, Ridge has an iconic quality, yet its freshness<br />

and simplicity make this work Wrst and foremost<br />

a sensuous optical experience, the product of an<br />

artist in love with the interaction of paint and<br />

surface and the inWnite ways of exploring their<br />

convergence.<br />

Lisa N. Peters<br />

1. Notable sources on <strong>Christensen</strong> include Sharon L.<br />

Kennedy, Douglas Drake, and Karen Wilkin, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>:<br />

Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat. (Kansas City, Mo.: Kemper<br />

Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009); <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: <strong>The</strong><br />

Plaid <strong>Paintings</strong>, exh. cat. (including an interview with<br />

Elaine Grove) (New York: <strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, 2009); and<br />

Stephen Westfall, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>, exh. cat. (New York:<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, 2007).<br />

2. <strong>The</strong>se paintings were the subject of <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Plaid <strong>Paintings</strong> (2009).<br />

3. Grace Glueck, “A Happy New Year?” Art in America 59<br />

(January–February 1971), 27.<br />

4. Cited in Sharon L. Kennedy, “Charting His Course:<br />

<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>’s Early Years,” in Kennedy, Drake, and<br />

Wilkin, 2009, 10.<br />

5. Valentin Tatransky, “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,” Arts Magazine<br />

(May 1982), 11.<br />

6. Hilton Kramer, “Art: Show of New Works Sets<br />

Example at <strong>Modern</strong>,” New York Times, February 13, 1981.<br />

7. John Ashbery, “Pleasures of Paperwork,” Newsweek,<br />

March 16, 1981, 94.<br />

8. John ElderWeld, New Work on Paper 1, exh. cat.<br />

(New York: Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art, 1981), 12.<br />

9. James Monte, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: <strong>The</strong> Circular <strong>Paintings</strong>,<br />

exh. cat. (New York: Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, Inc., 1991).<br />

10. James Monte, “A Note on <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>’s<br />

<strong>Paintings</strong>,” in <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: A Survey, 1966–1990, exh. cat.<br />

(East Hampton, N.Y.: Vered Gallery, 1990). See also Barbara<br />

Rose, Miró in America, exh. cat. (Houston, Tex.: Museum of<br />

Fine Arts, 1982).<br />

11. On this term and Greenberg’s conception of it, see<br />

Karen Wilkin, “Notes on Color Field Painting,” in Wilkin,<br />

Color as Field: American Painting, 1950–1975, exh. cat. (New<br />

York: American Federation of Arts in association with Yale<br />

University Press, New Haven, Conn., 2007), 11–75.<br />

12. Clement Greenberg’s statement appears in <strong>Dan</strong><br />

<strong>Christensen</strong>: A Survey, 1966–1990, exh. cat. (East Hampton,<br />

N.Y.: Vered Gallery, 1990).<br />

13. Unpublished typescript, “Interview with <strong>Dan</strong><br />

<strong>Christensen</strong> by R. Phillips and W. Hamilton,” November 2,<br />

1974, part 1, 2.<br />

7

8<br />

beulah land, 1978, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 29 1 ⁄ 8 x 68 3 ⁄ 4 in.

idge, 1976, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 78 x 90 1 ⁄ 2 i n .<br />

9

atlantic champagne, 1979, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 69 1 ⁄ 2 x 131 1 ⁄ 2 in.<br />

11

12<br />

polarstar, 1978, AcryLic And gesso on cAnvAs, 26 x 39 1 ⁄ 2 in.

song of ceylon, 1979, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 73 1 ⁄ 2 x 91 in.<br />

13

14<br />

norseland, 1979, AcryLic And gesso on cAnvAs, 43 x 63 in.

little ceasar, 1979, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 60 3 ⁄4 x 57 3 ⁄4 in.<br />

15

16<br />

infield seltzer, 1980, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 102 x 66 in.

ig bad wolf, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 43 1 ⁄ 4 x 69 in.<br />

17

18<br />

sissystrut, 1980, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 69 x 52 1 ⁄ 2 i n .

santali, 1980, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 66 3 ⁄ 4 x 6 2 i n .<br />

19

20<br />

coahoma, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 20 x 1 5 i n .

yellow bower, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 71 1 ⁄ 4 x 40 in.<br />

21

22<br />

carib cocktail, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 68 x 53 1 ⁄ 4 in.

topsy part ii, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 67 x 6 9 i n .<br />

23

24<br />

tokyo tattoo, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 87 x 77 7 ⁄ 8 in.

jambo caribe, 1981, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 64 x 5 2 i n .<br />

25

26<br />

troubadour, 1988, AcryLic on cAnvAs, 90 7 ⁄ 8 x 75 in.

checkList of the eXhiBition<br />

AtLAntic chAmpAgne 1979<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 69H 2 131H in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1979 “Atlantic Champagne”<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 131H x 69H<br />

BeuLAh LAnd 1978<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 29J 2 68I in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1978 acrylic on canvas “Beulah Land”<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 29G x 68I<br />

Big BAd woLf 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 43G 2 69 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981 / “Big Bad Wolf”<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 43H x 69<br />

cAriB cocktAiL 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 68 2 53G in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

acrylic on canvas © D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981 “Carib Cocktail”<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 53G x 68<br />

coAhomA 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 20 2 15 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981 / “Coahoma”<br />

infieLd seLtZer 1980<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 102 2 66 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1980 “Infield Seltzer” acrylic on canvas<br />

JAmBo cAriBe 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 64 2 52 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso: acrylic on<br />

canvas “Jambo Caribe” © D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981<br />

LittLe ceAsAr 1979<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 60I 2 57I in.<br />

Signed on verso: © D. <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

Inscribed on stretcher: “Little Ceasar” /<br />

(for Jimmy Lu) / 57I x 60I<br />

norseLAnd 1979<br />

Acrylic and gesso on canvas, 43 2 63 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1979 “Norseland” acrylic &<br />

gesso on canvas / © D. <strong>Christensen</strong><br />

poLArstAr 1978<br />

Acrylic and gesso on canvas, 26 2 39H in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso: D. <strong>Christensen</strong> /<br />

“Polarstar” / 1978 / acrylic & gesso on canvas<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 39H x 26<br />

ridge 1976<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 78 2 90H in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1976 “Ridge” / 78 x 91<br />

sAntALi 1980<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 66I 2 62 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1980 “Santali” acrylic on canvas<br />

sissystrut 1980<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 69 2 52H in.<br />

Signed and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> “Sissystrut” acrylic on canvas<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 69 x 52H<br />

song of ceyLon 1979<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 73H 2 91 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1979 “Song of Ceylon” acrylic on canvas<br />

tokyo tAttoo 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 87 2 77M in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

“Tokyo Tattoo” © D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981 acrylic on canvas<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 77I x 87<br />

topsy pArt ii 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 67 2 69 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981 / Topsy Part II<br />

trouBAdor 1988<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 90M 2 75 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso:<br />

© D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1988 “Troubadour”<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 91 x 75<br />

yeLLow Bower 1981<br />

Acrylic on canvas, 71G x 40 in.<br />

Signed, dated, and inscribed on verso: acrylic<br />

on canvas / © D. <strong>Christensen</strong> 1981 “Yellow Bower”<br />

Inscribed on stretcher: 40 x 71G<br />

27

28<br />

dAn christensen<br />

b. 1942, Cozad, Nebraska<br />

d. 2007, Springs, East Hampton, New York<br />

1964, received B.F.A., Kansas City Art Institute<br />

s e L e c t e d s o L o e X h i B i t i o n s<br />

André Emmerich Gallery, New York, 1969, 1971,<br />

1972, 1974, 1975, 1976.<br />

Edmonton Art Gallery, Alberta, Canada, 1973.<br />

University of Nebraska at Omaha Art<br />

Gallery, 1980.<br />

Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, Inc., New York, 1981,<br />

1982, 1983, 1984, 1991, 1999, 2000.<br />

Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State<br />

University, Kansas, 1984.<br />

Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown,<br />

Ohio, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: A Forty Year Survey,<br />

2001–2.<br />

Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York,<br />

Selections From a Retrospective, 2002–3.<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, New York, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,<br />

2007.<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> Gallery, llc at East Hampton, New<br />

York, Sculpture by Elaine Grove and <strong>Paintings</strong> by<br />

<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>, 2007.<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, New York, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Plaid <strong>Paintings</strong>, 2009.<br />

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art,<br />

Kansas City, Missouri, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: Forty<br />

Years of Painting, 2009 (also shown at Sheldon<br />

Museum of Art, University of Nebraska,<br />

Lincoln, 2009–10).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Armory Show, New York, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,<br />

2011.<br />

s e L e c t e d g r o u p e X h i B i t i o n s<br />

Oberlin College, Ohio, 1966.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

Annual, 1967.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

Recent Acquisitions, 1968.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art,<br />

RidgeWeld, Connecticut, Highlights of the 1968–<br />

69 Art Season, 1969.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

Annual, 1969.<br />

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.,<br />

Biennial, 1969.<br />

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York,<br />

<strong>The</strong>odoran Award Group, 1969.<br />

St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts, Washington<br />

University, Missouri (now <strong>The</strong> Mildred Lane<br />

Kemper Art Museum), Here and Now, 1969.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Katonah Gallery, New York, Color, 1970.<br />

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, BuValo, New York,<br />

Color and Field 1890–1970 (also shown at the<br />

Dayton Art Institute, Ohio, and at the Cleveland<br />

Museum, Ohio), 1970–71.<br />

Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, Art of<br />

the Decade 1960–70: <strong>Paintings</strong> from the Collections<br />

of Greater Detroit, 1971.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

<strong>The</strong> Structure of Color, 1971.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

Lyrical Abstraction, 1971.<br />

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, BuValo, New York,<br />

Six Painters (also shown at the Baltimore<br />

Museum of Art and at the Milwaukee Art<br />

Center), 1971–2.<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Abstract Painting in<br />

the 70s, 1972.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

Annual, 1972.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art,<br />

RidgeWeld, Connecticut, 1973.<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,<br />

Biennial, 1973.<br />

Moore College of Art, Philadelphia, <strong>Paintings</strong>,<br />

1973.<br />

Museo Bellas Artes, Caracas, Venezuela, El lenguaje<br />

del Color, 1975.<br />

Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania,<br />

Freedom in Art, 1976.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art,<br />

RidgeWeld, Connecticut, Collector’s Choice, 1977.<br />

Edmonton Art Gallery, Alberta, Canada, New<br />

Abstract Art, 1977.<br />

University of Nebraska, Omaha, Expressionism in<br />

the 70s, 1978.<br />

Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, Memphis, American<br />

Masters of the Sixties and Seventies, 1978.<br />

Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art, New York, New Work<br />

on Paper I (also shown at the Museum of Fine<br />

Arts, Houston, and at the La Jolla Museum of<br />

Contemporary Art, California), 1981.<br />

Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of<br />

Nebraska, Lincoln, Kansas City, 1981.<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Miró in<br />

America, 1982.

Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown,<br />

Ohio, 46th Annual National Midyear Show, 1982.<br />

<strong>The</strong> University of Oklahoma at Norman, Points of<br />

View: 1982, 1982.<br />

P.S.1, New York, Special Projects, 1983.<br />

Baruch College Gallery, New York, 1985.<br />

Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City,<br />

Missouri, 1985.<br />

Spencer Museum, Lawrence, Kansas, Pop Op Plus,<br />

1985.<br />

Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art, New York, Philip Johnson:<br />

Selected Gifts, 1985.<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York,<br />

Artists of the Region Invitational, 1986.<br />

Grey Art Gallery, New York, 1969: A Year<br />

Reconsidered, 1994.<br />

P.S.1, New York, Richard Bellamy Memorial Show,<br />

1998.<br />

Portland Art Museum, Oregon, Clement Greenberg:<br />

A Critic’s Collection, 2000.<br />

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas<br />

City, Missouri, Big <strong>Paintings</strong>, 2002.<br />

Edmonton Art Gallery, Alberta, Canada,<br />

Edmonton Contemporary Artists Tenth Anniversary<br />

Exhibition, 2002.<br />

Neuesmuseum, Nürnberg, Germany, Einfach<br />

Kunst, 2002.<br />

Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of<br />

Nebraska, Lincoln, Big Canvas—<strong>Paintings</strong> from<br />

the Permanent Collection, 2003.<br />

Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York,<br />

Three East End Artists, 2003.<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> Gallery, llc at East Hampton,<br />

New York, Art and the Garden, 2005.<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> Gallery, llc at East Hampton, New<br />

York, Artists and Nature on Eastern Long Island:<br />

1940s to the Present, 2005.<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> Gallery, llc at East Hampton,<br />

New York, Long Island Abstraction—1950s to the<br />

Present, 2006.<br />

Weatherspoon Art Museum Greensboro, North<br />

Carolina, High Times Hard Times: New York<br />

Painting, 1967–1975 (also shown at the American<br />

University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center,<br />

Washington, D.C., and at the National Academy<br />

Museum, New York), 2006–7.<br />

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California,<br />

Colorscope: Abstract Painting, 1960–1979, 2010.<br />

s e L e c t e d r e f e r e n c e s<br />

Max KozloV, “Light as Surface: Ralph Humphrey<br />

and <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,” Artforum (February<br />

1968), 26–30.<br />

Ann Ray Martin and Howard Junker, “<strong>The</strong><br />

New Art: It’s Way, Way Out,” Newsweek 29<br />

(July 1968), 56–63.<br />

Barbara Rose, “Gallery without Walls,” Art in<br />

America (March–April 1968), 71.<br />

Emily Wasserman, “Corcoran Biennial,” Artforum<br />

(April 1969), 71–74.<br />

“To See, To Feel, Painting—Dervish Loops,” Time<br />

Magazine (May 30, 1969), 64.<br />

Grace Glueck, “Like a Beginning,” Art in America<br />

(May–June 1969), 116–19.<br />

“Art in New York, Midtown, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,”<br />

Time Magazine (June 6, 1969), 2.<br />

John Gruen, “<strong>The</strong> Whoosh in the Work,” New York<br />

Magazine (June 9, 1969), 57.<br />

Emily Wasserman, “New York,” Artforum (Summer<br />

1969), 61–62.<br />

Douglas M. Davis, “This is the Loose-Paint<br />

Generation,” National Observer (August 4,<br />

1969), 20.<br />

Scott Burton, Art News (September 1969), 16.<br />

Larry Aldrich, “Young Lyrical Painters,” Art in<br />

America (November–December 1969), 104–13.<br />

Carter RatcliV, “<strong>The</strong> New Informalists,” Art News<br />

(February 1970), 46–50.<br />

Charlotte Curtis, “When Ethel Scull Redecorates,<br />

it is Art News,” New York Times, February 27,<br />

1970, 33.<br />

Douglas Davis, “<strong>The</strong> New Color Painters,”<br />

Newsweek (May 4, 1970), 84–85.<br />

Peter Plagens, Artforum (May 1970), 82–83.<br />

Willis Domingo, “Color Abstractionism: A Survey<br />

of Recent American <strong>Paintings</strong>,” Arts Magazine<br />

(December 1970), 39.<br />

Grace Glueck, “A Happy New Year?” Art in<br />

America (January–February 1971), 26–27.<br />

Robert Pincus-Witten, “New York,” Artforum<br />

(April 1971), 75.<br />

Edward B. Henning, “Color & Field,” Art<br />

International (May 1971), 46–50.<br />

Carter RatcliV, “New York Letter: Spring,<br />

Part III,” Art International (Summer 1971),<br />

95–99, 105.<br />

Jeanne Siegel, “Around Barnett Newman,” Art<br />

News (October 1971), 42–43.<br />

29

30<br />

Marcia Tucker, <strong>The</strong> Structure of Color (New York:<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, 1971).<br />

James N. Wood, Six Painters (BuValo, N.Y.:<br />

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1971).<br />

Hilton Kramer, “Dickinson Motifs Keep Tradition<br />

Alive,” New York Times, October 28, 1972, 23.<br />

Jeanne Siegel, Art News (November 1972), 79.<br />

Kenworth MoVett, Abstract Painting of the 70s<br />

(Boston, Mass.: Museum of Fine Arts, 1972).<br />

James K. Monte, Six New York Artists: <strong>Paintings</strong><br />

(Philadelphia, Pa.: Moore College of Art, 1973).<br />

Karen Wilkin, “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: Recent<br />

<strong>Paintings</strong>,” Art International (Summer 1974), 57.<br />

Ingeborg Hoesterey, “Ausstellung,” Art International<br />

(Summer 1976), 31–32.<br />

Donald Doe, Expressionism in the Seventies (Omaha,<br />

Nebr.: University of Nebraska at Omaha, 1978).<br />

Grace Glueck, “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,” New York Times,<br />

March 16, 1979, 24.<br />

John Ashbery, “Out of Left Field,” New York<br />

Magazine (April 2, 1979), 68.<br />

Donald Doe, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: <strong>Paintings</strong> from the<br />

70s (Omaha, Nebr.: University of Nebraska at<br />

Omaha, 1980).<br />

John ElderWeld, New Work on Paper 1 (New York:<br />

Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art, 1981).<br />

Hilton Kramer, “Art: Show of New Works<br />

Sets Example at <strong>Modern</strong>,” New York Times,<br />

February 13, 1981, 61.<br />

Hilton Kramer, New York Times, “Art,” February 27,<br />

1981, c17.<br />

Kay Larson, “Drawing on Strength,” New York<br />

Magazine (March 9, 1981), 58–61.<br />

John Ashbery, “Pleasures of Paperwork,” Newsweek<br />

(March 16, 1981), 93–94.<br />

Valentin Tatransky, “New Work in New York,”<br />

Museum Magazine (July–August 1981), 64–68.<br />

Barbara Rose, Miró in America (Houston, Tex.:<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, 1982).<br />

Valentin Tatransky, “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,” Arts<br />

Magazine (May 1982), 11.<br />

Phyllis BraV, “11 East End Painters Illustrate Bold<br />

New Trends,” New York Times, September 14,<br />

1986, a1.<br />

<strong>Dan</strong> Cameron, “Before the Field: <strong>Paintings</strong> from the<br />

60s, at the <strong>Dan</strong>iel Newburgh Gallery,” Flash Art<br />

152 (May–June 1990).<br />

Phyllis BraV, “Social and Political Situations,” New<br />

York Times, Long Island Weekly [supplement],<br />

June, 17, 1991, 17.<br />

Roberta Smith, “A Color Field Painter From<br />

the 60s to Now,” New York Times, August 2,<br />

1991, c23.<br />

Ruth Bass, “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,” Art News<br />

(November 1991), 136.<br />

Lee Rosenbaum, “If It’s Not Popular, That’s<br />

Just Too Bad,” New York Times, March 7, 1993,<br />

h33–34.<br />

Holland Cotter, “Art in Review—‘1969: A Year<br />

Revisited,’” New York Times, July 15, 1994, c23.<br />

Holland Cotter, “Art in Review,” New York Times,<br />

July 22, 1994, c24.<br />

Hearne Pardee, “<strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>,” Art News<br />

(January 1995), 165–66.<br />

Karen Wilkin, “At the Galleries,” Partisan Review<br />

(Fall 1999), 640–52.<br />

Helen A. Harrison, “Landscapes of Fantasy,<br />

and a Devotion to Color,” New York Times,<br />

December 8, 2002, li21.<br />

Katherine B. Crum, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>—ReXections<br />

on a Retrospective (Southampton, N.Y.: Parrish<br />

Art Museum, 2002).<br />

Stephen Westfall, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong> (New York:<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, 2007).<br />

Elaine Grove, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: <strong>The</strong> Plaid <strong>Paintings</strong><br />

(New York: <strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, 2009).<br />

Sharon L. Kennedy, Douglas Drake, and<br />

Karen Wilkin, <strong>Dan</strong> <strong>Christensen</strong>: Forty Years<br />

of Painting (Kansas City, Mo.: Kemper<br />

Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009).

AwA r d s<br />

1992 Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant<br />

1986 Gottlieb Foundation Grant<br />

1969 Guggenheim Fellowship <strong>The</strong>odoran Award<br />

1968 National Endowment Grant<br />

m u s e u m c o L L e c t i o n s<br />

Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art Gallery,<br />

St. Joseph, Missouri<br />

Albright-Knox Gallery, BuValo, New York<br />

Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio<br />

Art Institute of Chicago<br />

Blanton Museum of American Art, University<br />

of Texas at Austin<br />

Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio<br />

Dayton Art Institute, Ohio<br />

Denver Museum of Art<br />

Detroit Institute of Art<br />

Edmonton Art Gallery, Alberta, Canada<br />

Eversen Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York<br />

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco<br />

Greenville County Museum of Art, South Carolina<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York<br />

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell<br />

University, Ithaca, New York<br />

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia<br />

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Indianapolis Museum of Art<br />

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art,<br />

Kansas City, Missouri<br />

Kunstmuseum, St. Gallen, Switzerland<br />

Ludwig Collection in the Wallraf-Richartz<br />

Museum, Cologne, Germany<br />

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York<br />

Mulvane Art Museum, Washburn University,<br />

Topeka, Kansas<br />

Museum für <strong>Modern</strong>e Kunst, Frankfurt am<br />

Main, Germany<br />

Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, Florida<br />

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago<br />

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas<br />

Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art, New York<br />

Museum of Nebraska Art, Kearney<br />

Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, Missouri<br />

Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York<br />

Portland Museum of Art, Oregon<br />

Saint Louis Art Museum<br />

San Francisco Museum of <strong>Modern</strong> Art<br />

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California<br />

Seattle Art Museum<br />

Sheldon Museum of Art, University of<br />

Nebraska, Lincoln<br />

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York<br />

Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas,<br />

Lawrence<br />

Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia<br />

Toledo Museum, Ohio<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York<br />

31

Published in the United States of America in 2011 by<br />

<strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong>, 53 East 58th Street, New York, NY 10022<br />

Copyright © 2011 <strong>Spanierman</strong> <strong>Modern</strong><br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,<br />

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by<br />

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or<br />

otherwise, without prior permission of the publishers.<br />

isbn 978-1-935617-07-5<br />

Photography: Roz Akin; Gary Mamay, pp. 13, 16, 23, 25<br />

Design: Amy Pyle, Light Blue Studio

d<br />

spAniermAn modern<br />

53 eAst 58th street new york, ny 10022-1617