ROUEN CERAMICS MUSEUM - Musées de Rouen

ROUEN CERAMICS MUSEUM - Musées de Rouen

ROUEN CERAMICS MUSEUM - Musées de Rouen

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>ROUEN</strong> <strong>CERAMICS</strong> <strong>MUSEUM</strong>

HISTORY OF THE<br />

<strong>CERAMICS</strong> <strong>MUSEUM</strong><br />

The story of the Ceramics Museum is closely linked to the growing interest shown<br />

by nineteenth-century <strong>Rouen</strong> collectors in the « faïence » (tin-glazed earthenware) of<br />

their city. In 1861, a group of collectors, un<strong>de</strong>r the lea<strong>de</strong>rship of the comte <strong>de</strong> Germiny,<br />

exhibited for the fi rst time some masterpieces from their collections of <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence<br />

at the Palais <strong>de</strong> Justice.<br />

As a direct result of this fi rst public presentation, the City of <strong>Rouen</strong> purchased the<br />

1100 ceramics from the exceptional collection formed by André Pottier (1799-1867)<br />

and installed them in 1864 in a gallery in the cloister of the Departmental Antiquities<br />

Museum. Pottier himself became the curator of this fi rst Ceramics Museum, and after<br />

his <strong>de</strong>ath his notes were collated and published in 1870 un<strong>de</strong>r the title Histoire <strong>de</strong> la<br />

faïence <strong>de</strong> <strong>Rouen</strong>. This was to be the fi rst of erudite publications on this subject.<br />

Gifts from further generous local collectors such as the Abbé Colas, Alfred Darcel,<br />

Gustave Gouellain and Gaston Le Breton further enriched the municipal ceramics<br />

collection, which was installed in a gallery in the newly built Musée <strong>de</strong>s Beaux-Arts,<br />

inaugurated in 1888.<br />

It was <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d in the 1930s to transfer these collections to the Hôtel d’Hocqueville,<br />

but it was not until 1984 that the Ceramics Museum fi nally opened to the public in this<br />

former townhouse.<br />

In 2009, the museum started to re<strong>de</strong>sign its ceramic display: the Masséot Abaquesne<br />

gallery has been renovated; a dining table and a dressing table have been created to<br />

show how faïence was used in the eighteenth century. In addition, an intimate pleasure<br />

gar<strong>de</strong>n has been <strong>de</strong>signed.<br />

Vase with fl ame top, <strong>Rouen</strong>, around 1730

THE HÔTEL D’HOCQUEVILLE<br />

Built on the foundations of the former La Cohue prison, which was <strong>de</strong>molished in 1655,<br />

the townhouse which now houses the Ceramics Museum was built in 1657 for Pierre<br />

<strong>de</strong> Bec<strong>de</strong>lièvre, seigneur d’Hocqueville and Premier Prési<strong>de</strong>nt of the Cour <strong>de</strong>s Ay<strong>de</strong>s<br />

of <strong>Rouen</strong>. Built of stone, the house stands between a paved courtyard and a terrassed<br />

gar<strong>de</strong>n, beyond which stands a timber-framed house of the fi fteenth century.<br />

Around 1740, the owners built a music pavilion shaped as a semi-rotunda at the far end<br />

of the gar<strong>de</strong>n. In the second half of the eighteenth century, the building was altered.<br />

A pavilion was ad<strong>de</strong>d to the main building, providing the fi rst fl oor with a majestic<br />

entrance hall and a grand staircase.<br />

In 1775, Esprit Robert Marie Le Roux, baron d’Esneval, purchased the Hôtel<br />

d’Hocqueville from the heirs of the Bec<strong>de</strong>lièvre family. He renewed the interior <strong>de</strong>coration<br />

of the reception rooms to make them conform to the neo-classical taste of the<br />

period. This <strong>de</strong>coration remained in situ until its partial dismantling in 1910. In 1790,<br />

the house was sold to the Delahaye-Descours family, and then in 1826 to the Bataille <strong>de</strong><br />

Bellegar<strong>de</strong> family. In 1910, after the <strong>de</strong>ath of Albert Bataille <strong>de</strong> Bellegar<strong>de</strong>, the collector<br />

Paul Guilbert moved in.<br />

In 1936, the City of <strong>Rouen</strong> purchased the Hôtel d’Hocqueville to house the ceramics<br />

collection for which there was not enough room in the Musée <strong>de</strong>s Beaux-Arts. But for<br />

a long time the building was used for different purposes, including by the local music<br />

college, until it was fi nally arranged as a ceramics museum and opened as such in 1984.

THE MASSÉOT<br />

ABASQUENE GARDEN<br />

The gar<strong>de</strong>n has been re<strong>de</strong>signed. Set on a terrace, with its walls and outbuildings, its<br />

historical origin has been enhanced with contemporary aesthetics. A glazed stoneware<br />

gar<strong>de</strong>n fi gure from Sèvres, dating from around 1920, now presi<strong>de</strong>s over the centre of<br />

the lawn.<br />

The gar<strong>de</strong>n has been renamed in honour of Masséot Abasquene, the fi rst great Normandy<br />

ceramist, who worked in <strong>Rouen</strong> from 1526 to 1564. In its renewed form, it has<br />

closer links with the building and the collections it houses.<br />

God Pan<br />

Sèvres manufactory, sculptor Maignan author<br />

of the mo<strong>de</strong>l (1913). 1923-1930. Glazed stoneware

1<br />

16 th CENTURY<br />

2<br />

THE COLLECTIONS<br />

17 th CENTURY<br />

With more than five thousand pieces, the museum is able to<br />

show the most important public collection in France of faïence<br />

ma<strong>de</strong> in <strong>Rouen</strong>. On three fl oors are presented a complete history<br />

of <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence, from the sixteenth century to the end of<br />

the eighteenth century. While <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence accounts for more<br />

than two thirds of the museum’s collection, collections of other<br />

faïence help to place <strong>Rouen</strong> in the context of european ceramics,<br />

from the fi fteenth century to the 1930s.<br />

The visit starts with a display of the earliest european faïence: maiolica,<br />

produced in Italy from the fi fteenth to the seventeenth century.<br />

It continues with the production of the early <strong>Rouen</strong> workshops of<br />

Masséot Abaquesne (around 1550 to before 1564) in the second half<br />

of the sixteenth century, and with a presentation of French glazed<br />

earthenware of the sixteenth to the nineteenth century.<br />

On the fi rst and second fl oors, the seventeenth and eighteenth<br />

century galleries form the heart of the collections. Here are shown<br />

the masterpieces of <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence: blue monochrome, radiating<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration in blue and red, ocre niellé, chinoiseries and cornucopia<br />

<strong>de</strong>signs… Groups of objects from the Low Countries, Nevers,<br />

Lille and Moustiers are displayed with them to invite comparison.<br />

After these can be seen nineteenth and twentieth century porcelain<br />

from the Sèvres national porcelain factory. And fi nally two galleries<br />

with general porcelain and creamware displays.<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

1. Tiled fl oor from the<br />

Bastie d’Urfé<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, workshop of Masséot<br />

Abaquesne, around 1557<br />

2. Dish, Le Dévouement <strong>de</strong><br />

Marcus Curtius<br />

Italy, Castel Durante,<br />

around 1550-1560<br />

3. Dish, Esther aux pieds<br />

d’Assuérus<br />

Fontainebleau workshop (also<br />

known as Avon), early seventeenth<br />

century<br />

4. Dish with arms,<br />

probably those of Poterat<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, workshop of Edme Poterat,<br />

1647<br />

5. Bust of Winter<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, Poterat workshop,<br />

late seventeenth century<br />

6. Helmet-shaped ewer<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, around 1720<br />

7. Bowl<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, around 1725<br />

8. Tray, Triomphe <strong>de</strong><br />

Neptune<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, 1726<br />

9. Teapot from a service<br />

chinois réticulé<br />

Sèvres, 1872-1878<br />

10. Fennel coffepot<br />

Sèvres, 1898-1900<br />

18 th CEN

TURY<br />

6<br />

7<br />

19 th CENTURY<br />

<strong>ROUEN</strong> FAIENCE<br />

8<br />

20 th CENTURY<br />

The history of <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence stretches over nearly three hundred years, from the sixteenth<br />

to the end of the eighteenth century. <strong>Rouen</strong>’s success is due to the coming<br />

together of several positive factors: a good quality clay, a trading and transport network<br />

helped by the Seine river, and a rich urban aristocracy, which formed a broad base of<br />

clients both as regular purchasers and in the or<strong>de</strong>ring of prestigious pieces.<br />

In about 1526, Masséot Abaquesne, a potter from Normandy, set up his workshop in<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>. In 1644, the Queen Regent Ann of Austria granted an exclusive patent to Nicolas<br />

Poirel, lord of the manor of Grandval and a court offi cial, to manufacture tin-glazed<br />

earthenware in <strong>Rouen</strong> for the next fi fty years. His manufactory, on the left bank of the<br />

Seine, was run by Edme Poterat, who purchased the patent from Poirel <strong>de</strong> Grandval in<br />

1674. The Poterat family was to <strong>de</strong>velop <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence until the end of the seventeenth<br />

century, so that it became the equal of the other important faïence producing centres<br />

such as Nevers and Lille. In around 1698, the Poterat family’s exclusive patent came to<br />

an end, and further manufactories were foun<strong>de</strong>d.<br />

The fi rst half of the eighteenth century was a gol<strong>de</strong>n age for <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence: eighteen<br />

factories were foun<strong>de</strong>d in the Saint-Sever quarter on the left bank. This competitive<br />

atmosphere resulted in the production of many masterpieces of painting and sculpture,<br />

with newly-<strong>de</strong>veloped fi ring techniques and styles of <strong>de</strong>coration. In the second half of<br />

the eighteenth century, the <strong>Rouen</strong> factories continue to produce high-fi red faïence,<br />

though this technique limited the range of available colours to fi ve. But at this period<br />

competition came through new products such as porcelain, creamware and low-fi red<br />

faïence, which all had a greater palette of colours. The <strong>de</strong>cline started in the 1770s,<br />

with the factories closing one after the other in the fi rst half of the nineteenth century.<br />

9<br />

10

A TABLE LAID WITH <strong>ROUEN</strong> FAÏENCE<br />

FOR THE DESSERT COURSE<br />

A table has been laid with a <strong>de</strong>ssert course of the end of the eighteenth century, in this<br />

salon with its Louis XVI <strong>de</strong>coration. It inclu<strong>de</strong>s <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence with blue monochrome<br />

painting of the early eighteenth century, as well as eighteenth century glass.<br />

« Service à la française » is the name given to the way of laying a table and serving<br />

dishes to the guests which was in use until the early nineteenth century. All the dishes<br />

are brought to the table at the same time and displayed in a symetrical manner. We are<br />

told by Alexandre Grimod <strong>de</strong> la Reynière in his Almanach <strong>de</strong>s gourmands of 1804 that a<br />

grand dinner normally comprised four courses: « the fi rst inclu<strong>de</strong>d the potages (stews<br />

and soups), the hors-d’œuvre (starters), the relevés (spicy dishes) and the entrées; the<br />

second the roasts and salads; the third cold patés and all kinds of entremets (various<br />

cold dishes); fi nally the <strong>de</strong>ssert, which inclu<strong>de</strong>d fruit, fruit compotes, biscuits, cheese,<br />

a variety of sweets and pastries, jams and ices ». In the eighteenth century, the table<br />

became a true visual <strong>de</strong>light with lavish ephemeral <strong>de</strong>corations symetrically arranged:<br />

the various serving dishes were placed according to specifi c plans, with elaborate centrepieces<br />

ma<strong>de</strong> of silver or sugar surroun<strong>de</strong>d by pyramids of fruit and sweets on special<br />

trays of different heights and sizes.<br />

The table laid here bears witness to the variety of shapes which can be found on the<br />

table: in the centre, a footed tazza on which stand stemmed glasses used for glazed<br />

fruit (called « gobichons » in Gillier’s Le Cannaméliste français of 1768), sugar casters,<br />

small glass footed trays known as « guéridons », cruet stands, a spice box containing<br />

pepper, nutmeg and cloves, a salt cellar, bread baskets and bowls for compotes, creams<br />

or jellies.<br />

Until the nineteenth century, for formal dinners, servants would stand behind each<br />

guest, handing them glasses and taking them away once they had drunk, so that glasses<br />

do not remain on the table. The various necessities for serving wine, such as bottles,<br />

glasses and wine coolers were placed on console tables or si<strong>de</strong>boards. By the end of the<br />

eighteenth century, it had become usual in intimate dinners such as the one recreated<br />

here to place glasses, <strong>de</strong>canters and wine coolers full of ice on the table, where they<br />

did not have a specifi cally or<strong>de</strong>red place.

The table laid with <strong>Rouen</strong> faience for the <strong>de</strong>ssert course and the large <strong>de</strong>corative chargers<br />

The large hanging dishes bear witness to the technical competence of <strong>Rouen</strong>’s faïence<br />

manufacturers, who produced, at the end of the seventeenth century and in the fi rst<br />

third of the eighteenth, large <strong>de</strong>corative dishes measuring 19 to 22 inches diameter.<br />

Decorated in the centre with coats of arms and on the bor<strong>de</strong>rs with radiating lambrequins,<br />

these large dishes in blue monochrome sometimes with red and ochre highlights<br />

are magnifi cent examples, often or<strong>de</strong>red by the aristocracy, and inten<strong>de</strong>d purely for<br />

display, either on the shelves of large si<strong>de</strong>boards, or, since most of them have two holes<br />

in the back, hanging on walls.

DRESSING TABLE<br />

This display shows various elements in use at the « toilette » (dressing table). The shapes<br />

of the most lavish silver fi ttings have inspired the <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence manufacturers. The<br />

toilette consisted of various events, from the intimate ablutions performed in private<br />

« cabinets », to the formal toilette which inclu<strong>de</strong>d the arrangement of hair, make-up<br />

and dress. Carefully scripted so as to be performed in public in a bedroom, the formal<br />

toilette was a social occasion after the « lever » (formal act of rising from one’s bed),<br />

and could be the scene of business meetings, courtesy calls or even to receive a suitor.<br />

On a table with linen and muslin skirting are displayed various objects in faïence, silver,<br />

glass and wood used for a lady’s toilette in the second half of the eighteenth century. The<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong> faïence pieces presented here have polychrome chinoiserie or cornucopia motifs.<br />

Lady at her dressing table, Moreau le Jeune<br />

Late eighteenth century. Engraving, Paris<br />

bibliothèque <strong>de</strong>s Arts décoratifs

GLOSSARY<br />

TECHNIQUE<br />

Ceramics: this generic term comes from the<br />

greek keramos meaning « clay ». It is used for all<br />

objects ma<strong>de</strong> of fi red clay.<br />

There are four major ceramic types, each with a<br />

particular composition of their paste and different<br />

ways of fi ring: pottery, stoneware, faïence and<br />

porcelain.<br />

Pottery or fi red earth: the ol<strong>de</strong>st ceramic produced<br />

by man. It is ma<strong>de</strong> of a basic clay fi red<br />

around 600 to 900°C. This fi rst fi ring turns the clay<br />

into a « biscuit » which may be painted and covered<br />

with a colourless lead-based glaze.<br />

Faïence or tin-glazed earthenware: this appeared<br />

in the Middle East by the eighth century, is found<br />

in Spain from the tenth to the fourteenth century,<br />

and in Italy from the thirteenth to the fourteenth<br />

century, before spreading to the remain<strong>de</strong>r of Europe.<br />

It is ma<strong>de</strong> of a mixture of malleable clays.<br />

After a fi rst fi ring around 800 to 900°C, the biscuit<br />

is dipped into a bath of glaze containing tin oxi<strong>de</strong>.<br />

Upon fi ring, this coating becomes impermeable<br />

and makes the whole surface white, so that it may<br />

be <strong>de</strong>corated by artists with colours. It is then<br />

fi red a second time, fi rst at around 500°C (known<br />

as low fi ring), and then up to around 1000°C to fi x<br />

the colours.<br />

From the middle of the eighteenth century, French<br />

faïence manufacturers used a new low fi red technique,<br />

around 600-700°C, which enabled a greater<br />

variety of colours to be employed, such as pink,<br />

pale green and gold.<br />

Stoneware: fi rst found in China around the<br />

fourth century, stoneware became wi<strong>de</strong>spread in<br />

the West during the Middle Ages. It is ma<strong>de</strong> of<br />

a clay containing a high proportion of silica, and<br />

becomes totally impermeable after its high temperature<br />

fi ring at around 1250°C. Most often of a<br />

grey or brown colour, stoneware is very opaque,<br />

and the extreme heat of its fi ring produces a very<br />

bon<strong>de</strong>d texture.<br />

Porcelain: this is the only ceramic through which<br />

you can shine a light, because its body is composed<br />

of white and translucent materials vitrifi<br />

ed by the heat of the kiln. There are two types<br />

of porcelain, known as soft paste (a mixture of<br />

chalk and sand) and hard paste (ma<strong>de</strong> of kaolin,<br />

feldspath and quartz). The fi rst French soft-paste<br />

porcelain was ma<strong>de</strong> in <strong>Rouen</strong> in the late seventeenth<br />

century, and the most famous soft-paste<br />

porcelain was produced at Sèvres, while Meissen<br />

in Germany is best known for its hard-paste porcelain.<br />

Maiolica: name given to Italian Renaissance faïence,<br />

as well as to the earliest French ones, either<br />

produced by Italians, or according to Italian technique<br />

and style (in the sixteenth and seventeenth<br />

century). Maiolica is often <strong>de</strong>corated with historical<br />

or mythological scenes (known as a istoriato).

STAGES IN THE<br />

MANUFACTURE<br />

OF <strong>ROUEN</strong> FAIENCE<br />

Biscuit: ceramic paste fi red at a high temperature<br />

without glaze or <strong>de</strong>coration<br />

High-fi red <strong>de</strong>coration: fi red biscuit is dipped in<br />

a bath of glaze then painted. It is then fi red at<br />

900°-1000° C. Only fi ve colours can be used at this<br />

temperature: blue, red, green, brown and yellow.<br />

Low-fi red <strong>de</strong>coration: this was <strong>de</strong>veloped in<br />

France in the middle of the eighteenth century.<br />

After the stages <strong>de</strong>scribed above more <strong>de</strong>coration<br />

is ad<strong>de</strong>d and the pieces are fi red at around 600°-<br />

700° C, allowing for further colours and sha<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

Glazing: pieces are dipped into a solution of the<br />

glaze components in water.<br />

DECORATION<br />

A compendiario: a type of <strong>de</strong>coration with a small<br />

palette of colours (blue, yellow or green). The<br />

white glazed ground remains visible.<br />

Chinoiserie: the East India Companies’ ships<br />

returned to Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth<br />

century with Chinese porcelain with oriental<br />

motifs such as dragons, pagods, or lush vegetation.<br />

These were copied fi rst in Dutch faïence,<br />

then all over Europe. In the eighteenth century,<br />

chinoiserie <strong>de</strong>coration became extremely fashionable,<br />

and was applied to all the branches of the<br />

<strong>de</strong>corative arts, such as tapestries or furniture.<br />

Grotesques: <strong>de</strong>corative motifs found from the<br />

Renaissance in the sixteenth century, after the<br />

discovery in Rome of Ancient sites (un<strong>de</strong>rground,<br />

therefore in grottoes), including Nero’s Domus<br />

Aurea. They continued to be fashionable in the<br />

seventeenth century; the Berain family of <strong>de</strong>signers<br />

are known for their grotesques at the time of<br />

Louis XIV.<br />

Lambrequin: <strong>de</strong>corative motifs shaped as repeated<br />

hanging fl aps of fabric or embroi<strong>de</strong>ry. They<br />

form the basis of <strong>de</strong>coration on <strong>Rouen</strong> faïence<br />

from the end of the seventeenth century.<br />

Ocre niellé: one of the more original forms of<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration at <strong>Rouen</strong>, usually found only on prestigious<br />

pieces. Areas of an ochre colour are overlaid<br />

with black scrolls, in the same way as niello<br />

<strong>de</strong>coration (a kind of enamel) is applied on silver.<br />

Templates: artists painted freehand, but sometimes<br />

with the help of templates. These sheets<br />

of paper or metal pierced with patterns of holes<br />

were applied to the pieces, and charcoal dust was<br />

sprinkled over them, allowing the motifs to appear<br />

on the objects.

GROUND FLOOR<br />

RECEPTION<br />

1 st FLOOR<br />

ENTRANCE<br />

1. How a faience is ma<strong>de</strong><br />

2. Italian Majolica<br />

Dish, Venus faisant forger les traits<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’Amour par Vulcain, Urbino, around 1530<br />

3. Masséot Abaquesne<br />

Albarello<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, workshop of Masséot Abaquesne, around 1545<br />

4. Glazed earthenware from Normandy<br />

Bernard Palissy and his followers<br />

German stoneware<br />

4<br />

3<br />

1 2<br />

2<br />

3

FIRST FLOOR<br />

5 6 7<br />

5. Edme Poterat, blue monochrome<br />

6. A table laid with <strong>Rouen</strong> faience<br />

7. Red and blue <strong>de</strong>coration, ocre niellé<br />

Dish, Le Bâtonnet et la charrue . <strong>Rouen</strong>, around 1725<br />

8. The Low Countries and Delft, Nevers,<br />

Lille and Moustiers<br />

Violin. Delft, around 1710<br />

9. Glass and the busts of the Seasons<br />

Bust, from the Seasons series, Autumn<br />

as Bacchus. Fouquay factory, around 1730<br />

A. Porcelain room<br />

(to see at the end of your visit,<br />

on the way down)<br />

A<br />

8<br />

8<br />

9<br />

2 nd FLOOR<br />

9<br />

7

SECOND FLOOR<br />

17<br />

10. Five colour <strong>de</strong>coration<br />

11. The dressing table and its fi ttings<br />

12. Panelling from the music room,<br />

vases with fl ame tops<br />

13. Faience painting and sculpture<br />

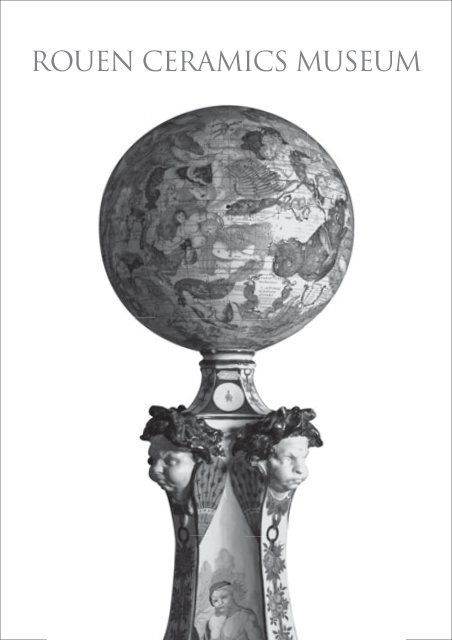

Terrestrial globe. <strong>Rouen</strong>, Le Coq <strong>de</strong> Villeray factory,<br />

painter Pierre II Chapelle, 1725, faience<br />

14. Sèvres<br />

Vase carré aux cariati<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

shape <strong>de</strong>signed by Albert Carrier-Belleuse, 1880<br />

15. Eclecticism, Art Nouveau and Art <strong>de</strong>co<br />

François Pompon, Hippopotamus. After 1918<br />

16. Pagods and Chinoiseries<br />

Bread basket . La Chasse au lion. <strong>Rouen</strong>, around 1735<br />

17. Rococo and cornucopia <strong>de</strong>coration,<br />

low-fi red faience<br />

B. Creamware (mezzanine)<br />

16<br />

15<br />

15<br />

14<br />

13<br />

16<br />

13<br />

Creamware gallery<br />

(mezzanine)<br />

12<br />

SORTIE<br />

14<br />

10<br />

11<br />

B

PRACTICAL<br />

INFORMATION<br />

OPENING DAYS AND TIMES<br />

Every day except Tuesday from 2pm to 6pm<br />

The museum is closed on 1 January, 1 and<br />

8 May, 14 July, 15 August, 1 and 11 November,<br />

and 25 December.<br />

ENTRANCE CHARGES<br />

Full charge : 3 ¤<br />

Reduced charge : 2 ¤<br />

Entrance is free to those un<strong>de</strong>r 26 and to the<br />

unemployed.<br />

No entrance charges are payable to the<br />

permanent collections on the fi rst Sunday<br />

of each month.<br />

MUSÉE DE LA CÉRAMIQUE<br />

Design: l’atelier <strong>de</strong> communication<br />

Photography Credits: © <strong>Musées</strong> <strong>de</strong> la ville <strong>de</strong> <strong>Rouen</strong> / © Agence Albatros<br />

INFORMATION AND RESERVATIONS<br />

ACCESS<br />

By bus: square Verdrel stop - rue Jeanne-d’Arc<br />

(4, 8, 11, 13) Beaux-Arts stop - rue Lecanuet<br />

(4, 5, 11, 13, 20)<br />

By Metrobus: main train SNCF station<br />

or Palais <strong>de</strong> Justice<br />

By train: <strong>Rouen</strong> station, fi ve minutes walk down<br />

the rue Jeanne d’Arc<br />

SERVICES<br />

Shop (catalogue of the collections, post cards,<br />

jewellery…)<br />

Cloakroom<br />

Visiting aids (French, braille, large print in French)<br />

Service <strong>de</strong>s Publics<br />

<strong>Musées</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Rouen</strong><br />

Esplana<strong>de</strong> Marcel Duchamp / 76000 <strong>Rouen</strong><br />

Tél. : + 33 (0)2 35 52 00 62 / Fax : + 33 (0)2 32 76 70 90<br />

publicsmusees@rouen.fr<br />

1, rue Faucon ou 94, rue Jeanne d’Arc / 76 000 <strong>Rouen</strong><br />

Tél. : + 33 (0)2 35 07 31 74 / Fax. : + 33 (0)2 35 15 43 23<br />

musees@rouen.fr<br />

www.rouen-musees.com<br />

Element from a table centrepiece<br />

Orléans, workshop of Bernard Perrot,<br />

late seventeenth century – early eighteenth century<br />

Cover: Celestial Globe<br />

<strong>Rouen</strong>, Le Coq <strong>de</strong> Villeray factory,<br />

painter Pierre II Chapelle, 1725, faïence