here - Nobility Associations

here - Nobility Associations

here - Nobility Associations

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 1 of 200

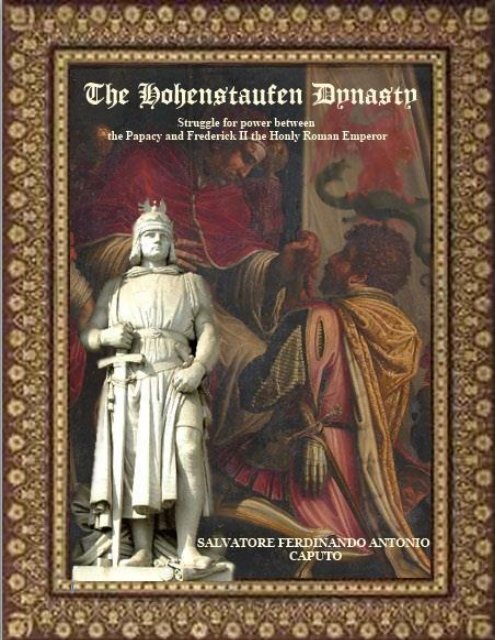

THE HOHENSTAUFEN DYNASTY<br />

SALVATORE FERDINANDO ANTONIO CAPUTO<br />

Front page: Giorgio Vasari Clemente IV hands his insignia to the captains of the Guelph<br />

Copyright © Salvatore Ferdinando Antonio Caputo 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this book<br />

shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means – electronic,<br />

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise– without written permission from the publisher.<br />

No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained <strong>here</strong>in. Although<br />

every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume<br />

no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting<br />

from the use of the information contained <strong>here</strong>in.<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 2 of 200

FOR THE DEFENSE OF TRADITION, FAMILY HISTORY AND<br />

LINEAGES<br />

Celebrating our heritage comes through in so many ways--we are who we are<br />

somewhat because of w<strong>here</strong> we come from. Although our past doesn't define us,<br />

our perspective of the world can largely be shaped by the faith, heritage and<br />

traditions we choose to hold on to.<br />

Other publications of Dr. Salvatore Ferdinando Antonio Caputo:<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty (2013)<br />

Who is noble included in the Almanach de Gotha - Goliardica Editrice s.r.l,<br />

Trieste (2013)<br />

Corrado I principe d´Antiocia Della Casa di Sveva (Ramo Caputo) - Edizioni<br />

Italo Svevo, Trieste (2012<br />

The Legitimacy of Non Reigning Royal Families - Edizioni Italo Svevo,<br />

Trieste (2012)<br />

Creation of Order of Chivalry (2012)<br />

The Royal House of Georgia - H.R.H. Crown Prince Nuzgar Bagration-<br />

Gruzisky Dynasty (2012)<br />

Mantra & Candle Magic (2003)<br />

The Magic of Metaphysics effects (2003)<br />

Reiki Fundamental (2003)<br />

Science & Christianity (2003)<br />

TOTAL CONSCIOUS SELF - Meditation and Visualization (2003)<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 3 of 200

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR<br />

The study of history, like the study of all disciplines in the humanities, enhances<br />

your knowledge, your ability to think well, and your ability to communicate. But<br />

history is also unique amongst humanities disciplines because it offers a particular<br />

kind of knowledge and a particular kind of critical thinking. History provides an<br />

understanding of the broad forces that have shaped the world in which we live. It<br />

allows us to perceive patterns of political, social and cultural life established over<br />

time—and it allows us to question such patterns. But history also invites us to<br />

descend below theory, to enter into time, and to understand the ways in which lived<br />

experience has both influenced and been shaped by the larger currents of politics,<br />

culture and society.<br />

The increasing interest in family history is one of the most significant aspects of<br />

contemporary cultural movement, and in this sense, the role of family history<br />

cannot be considered exhausted. Knowing our own history, or the history of our<br />

culture, is important because it helps us to know who we are while molding the<br />

future. Knowing history also provides a sense of empowerment to the learner. If a<br />

person studies his ancestry or personal history, this will provide them with a great<br />

deal of helpful information and may assist them in forming an identity of their<br />

own. Knowing who or what we have descended from or evolved from tells us w<strong>here</strong><br />

we come from and what the secrets of our past. Our family is the root of our being<br />

and the source of our creation.<br />

Going back in time is like going in search of ourselves and when something is found<br />

is like to find or discover something that we though we lost. It’s still fascinating to<br />

find our even simple things of ancient history, certainly even if not characterized by<br />

exceptional events, but not for this is less important and significant.<br />

Celebrating our heritage comes through in so many ways--we are who we are<br />

somewhat because of w<strong>here</strong> we come from. Although our past doesn't define us,<br />

our perspective of the world can largely be shaped by the faith, heritage and<br />

traditions we choose to hold on to.<br />

Our heritage was the greatest achievement of our ancestors, and our fathers kept it<br />

for us, we implant this heritage in the minds of our children, our heritage is a river<br />

full of light which we take continuously to guide us to the good, to the prosperity in<br />

the future. Our past is behind us but if we choose to forget it, we then choose to<br />

lessen the many sacrifices made by our ancestors.<br />

We live in an era determined by momentum and convenience. In such a time, it is<br />

easy to forget the personalities, lifestyles, events and epoch deeds which forged not<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 4 of 200

only America, but modern civilization as we know it. The study of history and<br />

genealogy provides a mode of reflection and acknowledgement of the people, places<br />

and processes responsible for the lives we enjoy today.<br />

The descendants of Corrado Caputo of Antioch in particular and the Holy Roman<br />

Empire are notable for the diversity of its people and for its ability to absorb their<br />

differences without denying their origins. It encourages respect for heritage and<br />

values the cultural attributes with which immigrants have and continue to enrich<br />

the American continent experience. Descendants of Corrado Caputo in particular<br />

and the Holy Roman Empire must recognize the opportunity and the obligation to<br />

offer and honor the best of their culture and heritage.<br />

I am not an Historian in the academic sense, I am sure I am not unique in saying I<br />

hated history at school. All those dates and wars and politics left me cold. I have<br />

consulted very few "original sources". Some of the things written are facts and<br />

events as reported by historians and by the most authoritative modern biographers<br />

of Frederick II Hohenstaufen, which I am deeply indebted and by their sources<br />

mainly Ernst Kantorowicz, Georgia Masson, Eberhard Horst, David Abulafia,<br />

Alberto Meriggi, Steves Runciman and Franco Cardini.<br />

By the years I then discovered my prime interest in history, and especially medieval<br />

history, though not exclusively so. In terms of weaning me towards later medieval<br />

history, I suppose firstly it was my family heritage, and the grandeur of its family.<br />

The writing of this work was also motivated by my obsession to know the origins of<br />

my family that urged me, for more than twenty five years, to search of this noble<br />

original family of Corrado Caputo Prince of Antioch of the House of Hohenstaufen,<br />

General Vicar of the island of Sicily, and grandson of the Emperor Frederick II. The<br />

Hohenstaufen House was a great German dynastic family of the Württemberg, in<br />

the Jurisdiction of Swabia, called also, particularly in Italy, “House of Swabia” and,<br />

in Germany “House of Staufen”.<br />

T<strong>here</strong>fore Corrado was of German origin and has far for his last name, before been<br />

Caputo, it was Hohenstaufen, and he was prince of Antioch. From the same<br />

Corrado the family took also origin of the family “Antiochia” (Antioch). One,<br />

t<strong>here</strong>fore, called himself from the coat of arms, other from the nobiliary title. Many<br />

are the branches of families derived from the sons of Corrado Caputo of Antioch<br />

and many are the branches derived by Corrado´s brothers whose father was<br />

Federico prince of Antioch and son to Frederick II.<br />

The fall of Corradino (Conradin of Swabia, grandson of Frederick II and cousins of<br />

Corrado of Antioch), in the battle of Tagliacozzo the 23 of August of 1268, marked<br />

the end of male legitimate succession: but it does not mean that all the offspring<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 5 of 200

had been exterminated. From the sons of Fredrick of Antioch the offspring’<br />

branches have arrived until our days. Corrado Caputo of Antioch escaped from the<br />

massacres ordered by Charles of Anjou because his mother, Margarita Poli and his<br />

wife Beatrice Lancia, had in their castle of Saracinesco, in hostage since 1267, some<br />

Nobles of Guelph part, the Lords Napoleone and Matteo Orsini, and had saved the<br />

life for interchanging with the powerful Cardinal Giovanni Gaetano Orsini (brother<br />

of the prisoners), future Pope Nicoló III 26 December 1277), then made them to<br />

swear fidelity to the Church. Conradin of Swabia was host in the Corrado Caputo’s<br />

Castle of Saracinesco (near Rome) the eve of the battle of Tagliacozzo.<br />

For many years I believed that the Castle of Saracinesco was not a place, a country<br />

or a city, town. Just in the February of 1995, while I was to Rome for business, the<br />

last day in the city ready to leave Italy, I learned that the Castle of Saracinesco was<br />

in a town just 55 kilometers from Rome. Naturally I rushed to the place and it was a<br />

great emotion for me to be able to walk in the center of the Castle streets. The<br />

characteristic of the Castle with narrow lanes don’t allow the access to vehicles, I<br />

had to park my car outside the boundaries.<br />

Once inside the Castle t<strong>here</strong> was a tourist office, without thinking twice, I entered<br />

to ask for information of the Castle and its history. Surprise after surprise, the<br />

employees informed me that a book about Corrado of Antioch was written by the<br />

Prof. Mark Orsola, President of the Association for Native place of Saracinesco, but<br />

unfortunately he was in that moment in Rome.<br />

Re-entered to Rome I put myself in telephone communication with the Prof. Orsola<br />

who explained to me that Saracinesco was founded by the Saracens that escaped<br />

from Pope Giovanni X in year 916. The Ghibelline Corrado of Antioch was the Lord<br />

of Saracinesco of which from XVII century most of the Castle was destroyed.<br />

Thanks to Prof. Orsola who, through my brother Gino who at that time was living<br />

in Rome, forwarded me a copy of his book, I have learned a lot more about our<br />

family heritage.<br />

The analysis of the situation of the origin of our descendant is the object of this<br />

research that, starting from a series of data and sources of various kinds, stops to<br />

describe the criteria for evaluating the quality of our House. Forming a table of<br />

parameters between the Caputo from middle class to those descended from<br />

Corrado of Antioch highlighting the figure of our direct ancestors, thus to discover<br />

whether or not we are worthy to use both coat of arms as well title of nobility from<br />

Caputo Princes of Antioch of the House of Hohenstaufen. I do not wish to take<br />

advantage of the use of the emblem and title of nobility with no false claims. Many<br />

people often wish to know the origins of his family, perhaps with the hidden<br />

personal desire to discover royal blood or the coat of arms of his family.<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 6 of 200

To us about the origin of forefather Caputo, that of Corrado of Antioch, grandson of<br />

Frederick II, reported by many Institutes of Heraldry, History of Naples and Sicily,<br />

we always had our doubts. We did not want to believe with certainly the proper<br />

elements of science of heraldry and genealogy, since our primary goal was to detect<br />

with proofs of the origin of this noble family. Counting of scientific texts, several<br />

sources of History and had access to certain definitive information, we<br />

extrapolated, strengthened and integrated into the origins of some other families<br />

who belonged to Caputo families to meet the founder of our House. Please note<br />

that our investigations were complete and productive. The surveys were not limited<br />

to the Ecclesiastical Archives and the Historical Archives, but obtained clues,<br />

traces, confirmations, surprises and curiosity, the names of our fathers and our<br />

mothers in the meticulous recording of the Vatican Library and the one from the<br />

Royal Library of Turin, which is a department, not open to the public, but only to<br />

scholars. We were able to photocopy material of Antioch from the original<br />

documents.<br />

In order to be able to trace the directed descendant, I had to ask the aid of the<br />

Heraldic Institute “Heraldic Coccia” in Florence and “Ancestor Ltd.” of England,<br />

the Heraldic Institute of Milan and finally the Center Heraldic Studies of Varese.<br />

Although a writer may work in private, a writer is never alone. To write is to<br />

communicate with other people: we write letters to share our lives with friends. We<br />

write business reports to influence managers' decisions. We write essays to convert<br />

readers to our vision of the truth. Without other people, we would have little reason<br />

to write. Just as we wish to touch people through our writing, we have been<br />

influenced by the writing of others.<br />

Will Rogers's famous quip, “All I know is just what I read in the papers,” has truth.<br />

We learn many things indirectly through the written word, from current and<br />

historical events to the collisions of subatomic particles and of multinational<br />

corporations. Even when we learn from direct experience, our perceptions and<br />

interpretations are influenced by the words of others. And though we may write<br />

private notes and diary entries to ourselves to sort out plans, thoughts, or feelings,<br />

we are nevertheless reacting to experiences and concepts and situations that come<br />

from our relationships with others.<br />

Our publishing may be subject to critics or applause it depends on whichever side<br />

the commentators are on. For all criticism is based on that equation: knowledge +<br />

taste ‗ meaningful judgment. The key word <strong>here</strong> is meaningful. People, who have<br />

strong reactions to a work, and most of us do, but don’t possess the wider erudition<br />

that can give an opinion heft, are not critics. Nor are those who have tremendous<br />

erudition but lack the taste or temperament that could give their judgment<br />

authority in the eyes of other people, people who are not experts.<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 7 of 200

Even among expert, personal opinions are numerals.<br />

I have myself attempted to visit personally the sites w<strong>here</strong> the more important<br />

episodes in the story of my ancestors took place; and I should like to thank all<br />

people in Italy who have facilitated my mission. I should also like to thank the staff<br />

of the village of Saracinesco for their courtesy and kindness.<br />

I have done my best to review all material posted on this book and believe correct<br />

at the time of publication; consequently, I consider the content in this volume to be<br />

useful and reliable sources of information.<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 8 of 200

PREFACE<br />

The House of Hohenstaufen, also known as the Swabian dynasty or<br />

the Staufen, was a dynasty of German monarchs in the High Middle Ages,<br />

reigning from 1138 to 1254. Three members of the dynasty were crowned Holy<br />

Roman Emperors. In 1194, the Hohenstaufens were granted the Kingdom of Sicily.<br />

The terms Hohenstaufen and Staufen also identified the family's Hohenstaufen<br />

Castle in Swabia, located on an eponymous mountain near Göppingen. This second<br />

castle was built by the first known member of the dynasty, Duke Frederick I.<br />

The founder of the line was the count Frederick (died 1105), who built Staufen<br />

Castle in the Swabian Jura Mountains and was rewarded for his fidelity to Emperor<br />

Henry IV by being appointed duke of Swabia as Frederick I in 1079. He later<br />

married Henry’s daughter Agnes. His two sons, Frederick II, duke of Swabia, and<br />

Conrad, were the heirs of their uncle, Emperor Henry V, who died childless in 1125.<br />

After the interim reign of the Saxon Lothar III, Conrad became German king and<br />

Holy Roman emperor as Conrad III in 1138. Subsequent Hohenstaufen rulers were<br />

Frederick I Barbarossa (Holy Roman emperor 1155–90), Henry VI (Holy Roman<br />

emperor 1191–97), Philip of Swabia (king 1198– 1208), Frederick II (king, 1212–50,<br />

emperor 1220–50), and Conrad IV (king 1237–54). The Hohenstaufen, especially<br />

Frederick I and Frederick II, continued the struggle with the papacy that began<br />

under their Salian predecessors, and were active in Italian affairs.<br />

Following the death of Henry V (r. 1106-25), the last of the Salian kings, the dukes<br />

refused to elect his nephew because they feared that he might restore royal power.<br />

Instead, they elected a noble connected to the Saxon noble family Welf (often<br />

written as Guelf). This choice inflamed the Hohenstaufen family of Swabia, which<br />

also had a claim to the throne. Although a Hohenstaufen became king in 1138, the<br />

dynastic feud with the Welfs continued. The feud became international in nature<br />

when the Welfs sided with the papacy and its allies, most notably the cities of<br />

northern Italy, against the imperial ambitions of the Hohenstaufen Dynasty. Their<br />

rule in south Italy was to be brief, lasting from 1194 to 1266. In many ways it was a<br />

continuous of the Norman period, but with the Greek and Arabic elements<br />

progressively displaced by Western ones, as the political and economic links of the<br />

Regno shifted northwards.<br />

Frederick II (26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250), was one of the most<br />

powerful Holy Roman Emperors of the Middle Ages and head of the House of<br />

Hohenstaufen. His political and cultural ambitions, based in Sicily and stretching<br />

through Italy to Germany, and even to Jerusalem, were enormous; however, his<br />

enemies, especially the popes, prevailed, and his dynasty collapsed soon after his<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 9 of 200

death. Historians have searched for superlatives to describe him, as in the case of<br />

Professor Donald Detwiler, who wrote:<br />

A man of extraordinary culture, energy, and ability – called by a contemporary<br />

chronicler stupor mundi (the wonder of the world), by Nietzsche the first<br />

European, and by many historians the first modern ruler – Frederick established in<br />

Sicily and southern Italy something very much like a modern, centrally governed<br />

kingdom with an efficient bureaucracy.<br />

Viewing himself as a direct successor to the Roman Emperors of Antiquity, he<br />

was Emperor of the Romans from his papal coronation in 1220 until his death; he<br />

was also a claimant to the title of King of the Romans from 1212 and unopposed<br />

holder of that monarchy from 1215. As such, he was King of Germany, of Italy,<br />

and of Burgundy. At the age of three, he was crowned King of Sicily as a co-ruler<br />

with his mother, Constance of Hauteville, the daughter of Roger II of Sicily. His<br />

other royal title was King of Jerusalem by virtue of marriage and his connection<br />

with the Sixth Crusade.<br />

He was frequently at war with the Papacy, hemmed in between Frederick's lands in<br />

northern Italy and his Kingdom of Sicily (the Regno) to the south, and thus he<br />

was excommunicated four times and often vilified in pro-papal chronicles of the<br />

time and since. Pope Gregory IX went so far as to call him the Antichrist.<br />

Frederick II inherited German, Norman, and Sicilian blood, but by training,<br />

lifestyle, and temperament he was "most of all Sicilian."Maehl concludes that, "To<br />

the end of his life he remained above all a Sicilian grand signore, and his whole<br />

imperial policy aimed at expanding the Sicilian kingdom into Italy rather than the<br />

German kingdom southward. "Cantor concludes, "Frederick had no intention of<br />

giving up Naples and Sicily, which were the real strongholds of its power. He was,<br />

in fact, uninterested in Germany.<br />

As a result, the WeIf-Hohenstaufen controversy took on a particular hue in Italy. It<br />

became a division between those who supported the pope and those who supported<br />

the emperor. It also gained a slightly different set of labels. When placed in Italian<br />

mouths, "WeIf" became "Guelf." It may seem a little harder to imagine how<br />

"Hohenstaufen" turned into "Ghibelline," but t<strong>here</strong> really is an explanation.<br />

Supporters of the Hohenstaufen used the battle- cry "Waiblingen," the name of a<br />

Hohenstaufen castle. It was that battle cry that came to be Italianized into<br />

"Ghibelline." As the thirteenth century progressed, the papal-imperial rivalry<br />

escalated sharply. The last great Hohenstaufen emperor was Frederick II, the<br />

wiliest, cruelest, most intelligent and least Christian of the lot. By the time he died<br />

in 1250, the popes were determined to obliterate Hohenstaufen influence in Italy.<br />

Shortly after, they did. Thus the Guelf-Ghibelline battle had an international<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 10 of 200

dimension; yet it also had a more regional one. The alignment of cities on one side<br />

or the other reflected their rivalry with one another for power within their own<br />

area. Thus predominantly Guelf Florence opposed Ghibelline Siena, its major rival<br />

for influence in Tuscany .Below the regional level, the controversy had a local level<br />

which reflected the rivalry of powerful families. Thus within Florence Guelf-<br />

Ghibelline alignments were often based on considerations more familial than<br />

ideological.<br />

Five members of the Hohenstaufen family were kings of Sicily; Henry VI (1104-<br />

1197), Frederick II (1197-1250), Conrad II/V or Conradin (1254-1258) and Manfred<br />

(1259-1260). Manfred´s rule was limited to the Sicilian kingdom; the others were<br />

also kings of Germany and of the regnum Italicum, effectively north and central<br />

Italy. Only Frederick II was fully king of both countries; most of the lives of Henry<br />

VI, Conrad IV and Conradin were passed in Germany. Henry VI was in Italy only<br />

for the last three years of his life, Conrad IV in 1252-1254 and Conradin for less<br />

than a year in 1267-1268. Manfred was technically a usurper, becoming king only<br />

on receipt of the false news of Conradin´s death and refusing to relinquish the post<br />

when it was learnt the young king was still alive. Hohenstaufen rule over the<br />

southern mainland and Sicily effectively ended in 1255, when Charles of Anjou,<br />

brother of the French king Louis IX and summoned by Pope Innocent IV to assume<br />

the Sicilian crown, defeated and killed Manfred at the battle of Benevento. The<br />

brief and tragic reign of Conradin was only an epilogue. Summoned from Germany<br />

by the Italian Ghibellines, the seventeen year old boy was defeated by Charles at the<br />

battle of Tagliacozzo in Abruzzo, just inside the frontier of the Regno, and after a<br />

mock trial was beheaded at Naples by the victor on 29 October 1268.<br />

After the dead of the Emperor Frederick II, Pope Innocence IV left marks to<br />

destroy the “Svevi” (Swabian): “Never leave this man and his poisonous family the<br />

scepter with which dominated the people of Christ!” and, other terrible sentence:<br />

“Extirpate name, body, and seed of the heirs of the Babylonian”. Innocence died in<br />

1254. Under his successor Urban IV and Clemente IV, more rigid and obstinate,<br />

brought the destruction to them.<br />

Most of the Hohenstaufen sovereigns were thus primary kings of Germany and<br />

concerned with the maintenance of royal authority in that much divided land, but<br />

since the regnum Italicum formed part of the empire they had also to cope with the<br />

papacy and the communal movement in the north. The literature on these aspects<br />

of their history is huge and we will only describe those perspectives interested in<br />

the presentation of our family memoir.<br />

While the Swabian dynasty in the legitimate line became extinct with the death of<br />

Corradin (Corradino) in 1268, the illegitimate offspring which Federico Prince of<br />

Antioch, continued for many generations. T<strong>here</strong> are many descendants of Frederick<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 11 of 200

II. In this volume we will be interested in the continuation of Federico of Antioch,<br />

son of Frederick II, who was made king of Antioch by his father in 1247.<br />

Federico of Antioch took the surname by the investiture of the father of the<br />

principality of Antioch (“Summonte” in the History of Naples, p. 2 F. 237). He<br />

married Margarita Poli, nephew of Pope Innocent III, and from them was born a<br />

primogenitor Corrado of Antioch (called Caputo), count of Alba, Celano, Loreto and<br />

Abruzzo. Filadelfo Mugnos 1 writes that this dynastic line is agreed by all historians.<br />

What has most stimulated some historians to deepen the study of Corrado of<br />

Antioch was the adventurous character of his whole human story: the feudal lord<br />

and knight, pirate and a Gentleman "was one of those men whose fate seems to be<br />

the Land Toys" (Ivi, page 190; cfr. N. Cilento, La cultura di Manfredi nel ricordo di<br />

Dante e la cultura sveva, Florence 1970, page 7-11).<br />

Undoubtedly, all this is not without charm, at least for a certain type of nineteenthcentury<br />

historiography. In reality, the documentation on him (even though he was<br />

on the political and military scene of the second half of the thirteenth century)<br />

provides almost exclusively indirect data: those exclusively from the narrative of<br />

events that saw as other major protagonists such as Corradino (Conradin) and the<br />

same Manfredi. It does not appear, however, safe to assume, that while apparently<br />

acting in their shadow, his role was never secondary.<br />

The lack of documents does not allow, however, resolving some of the nodes: first<br />

of all for the name of the family that echoes Eastern origins. This does not mean<br />

that the attempt to give an answer to this, albeit in the form of hypotheses, also<br />

appears useful to try to learn about the history of his family.<br />

We know that his father was Frederick of Antioch, but also his birth little is known,<br />

excepting for the fact that he was the son of Frederick II of the Swabia. It is not<br />

known with certainty w<strong>here</strong> and when Frederick of Antioch was born and who with<br />

certain was his mother. Loophole really serious for many historians who have<br />

excluded, for the name de Antiochia, with implications for the paternal lineage,<br />

stating that it could be linked precisely to the mother. This hypothesis, moreover,<br />

1 Filadelfo Mugnos (1607 – May 28, 1675) was an Italian historian, genealogist, poet and man of<br />

letters. He was born in Sicily at Lentini in 1607, but moved while young to Palermo. He obtained a<br />

doctorate in Law at the University of Catania. He was made a member of the Portuguese chivalric<br />

Order of Christ and of various learned academies of the day. Of his numerous historical works, the<br />

best known is the Teatro genealogico delle famiglie nobili, titolate, feudatarie ed antiche del<br />

fedelissimo regno di Sicilia viventi ed estinte, published in three volumes between 1647 and<br />

1670, which for many centuries has been the mainstay for knowledge about of Sicilian nobility.<br />

Filadelfo Mugnos died in Palermo on 28 May 1675<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 12 of 200

would seem to be supported by historians and chroniclers of the time, but with<br />

contradictions and uncertainties.<br />

Bartolomeo da Neocastro presents the mother of Frederick of Antioch as the fourth<br />

legitimate wife of Frederick II Hohenstaufen. Even The Pirro says that the mother<br />

of Frederick of Antioch is legitimate wife of the Emperor. According to these<br />

testimonies, t<strong>here</strong>fore, Frederick of Antioch should be considered the legitimate<br />

son of the Emperor and his fourth wife.<br />

We cannot fail to prefer other hypotheses such as that of Carosi, who, in reference<br />

to the mother of Frederick of Antioch, says that "we cannot say anything for sure."<br />

Of course the easiest explanation of the name "d´Antiochia" would be that the<br />

mother was descended from the Norman Bohemond d´Altavilla, son of Roberto<br />

Guiscard, as is well known, in the first crusades June 3 1098 conquered Antioch,<br />

w<strong>here</strong> he was named prince. Bohemond IV of Antioch married three times. From<br />

his first wife were born two daughters who died at an early age. From the second<br />

the other two, of which one died as a child and the other named Maria (Mary or<br />

Mathilde), was to be the legitimate wife of the emperor when he went to the<br />

Crusade because in 1294 she was still alive. From third wife of Bohemond were not<br />

females born.<br />

After Corrado of Antioch’s death, which occurred shortly after 1320, the<br />

descendants of Federico of Antioch divided into different branches, one remaining<br />

in the region of Lazio (Anticoli, Piglio), the other moved to Sicily, w<strong>here</strong> he<br />

obtained the County of Capizzi from King Peter of Aragon (his family member).<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 13 of 200

Contents<br />

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR ......................................................................................................... 4<br />

PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE OF THE GERMAN NATION ............. 19<br />

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE GUELPHS AND GHIBELLINES ................................................... 23<br />

FREDERICK I, DUKE OF SWABIA ............................................................................................. 29<br />

Origins as dukes of Swabia ........................................................................................................ 30<br />

Coat of arms ................................................................................................................................ 30<br />

Ruling in Germany ..................................................................................................................... 30<br />

FREDRICK II, DUKE OF SWABIA .............................................................................................. 31<br />

CONRAD III .................................................................................................................................... 32<br />

FREDERICK I HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR ................................................................................ 33<br />

Third Crusade and death ....................................................................................................... 35<br />

The Saleph River, now known as the Göksu. ...................................................................... 36<br />

Legend ...................................................................................................................................... 37<br />

Children ................................................................................................................................... 38<br />

HENRY VI HOHENSTAUFEN, HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE ....................................................... 39<br />

Coronation as Emperor ......................................................................................................... 40<br />

Crusade of 1197 ....................................................................................................................... 41<br />

German Crusade ..................................................................................................................... 42<br />

Death ........................................................................................................................................ 42<br />

Wife Constance ....................................................................................................................... 43<br />

FREDERICK II HOHENSTAUFEN, HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE ............................................... 43<br />

Marriage of father Henry VI ..................................................................................................... 45<br />

Birth .............................................................................................................................................. 46<br />

The Crusade of Frederick II, 1228-29 ...................................................................................... 47<br />

Frederick II in the Holy Land ................................................................................................... 48<br />

Thus the Emperor left Acre ....................................................................................................... 49<br />

Death of the Emperor ................................................................................................................ 50<br />

Henry VII Hohenstaufen *1211 - †1242 ................................................................................... 54<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 14 of 200

The Antichrist ............................................................................................................................. 56<br />

The wives and legitimate children of Frederick II ................................................................. 57<br />

Constance of Aragon .............................................................................................................. 57<br />

Jolanda of Brienne. ................................................................................................................ 58<br />

Isabella of England ................................................................................................................. 59<br />

Matilde Maria .......................................................................................................................... 59<br />

Bianca Lancia .......................................................................................................................... 60<br />

Frederick II illegitimate children ............................................................................................. 60<br />

Unknown name, Sicilian Countess. ............................................................................. 61<br />

Frederick of Pettorana ................................................................................................... 61<br />

Adelheid (Adelaide) of Urslingen ...................................................................................... 61<br />

Manna .............................................................................................................................. 62<br />

Richina ............................................................................................................................. 63<br />

Margaret (Margherita) of Swabia ................................................................................. 64<br />

Selvaggia .......................................................................................................................... 64<br />

Blanchefleur .................................................................................................................... 65<br />

Gerhard ............................................................................................................................ 65<br />

CATHEDRAL OF PALERMO, SICILY – ITALY ..................................................................... 66<br />

....................................................................................................................................................... 66<br />

The portrait of Frederick II ....................................................................................................... 67<br />

The Popes and Fredrick II ......................................................................................................... 68<br />

Universal power .......................................................................................................................... 71<br />

The Weakening of the Empire .................................................................................................. 71<br />

Innocent III ............................................................................................................................. 72<br />

Onorio III ................................................................................................................................. 73<br />

Gregory IX ............................................................................................................................... 73<br />

Innocent IV .............................................................................................................................. 74<br />

Background ............................................................................................................................. 75<br />

CONRAD IV .................................................................................................................................... 77<br />

MANFRED HOHENSTAUFEN, KING OF SICILY .................................................................... 78<br />

Kingship ....................................................................................................................................... 79<br />

CONRADIN OF SWABIA – SON OF CONRAD IV .................................................................... 81<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 15 of 200

Political and military career .................................................................................................. 82<br />

Saved the life of Corrado Caputo of Antioch ........................................................................... 84<br />

Legacy ....................................................................................................................................... 85<br />

Memorial by Thorvaldsen ..................................................................................................... 85<br />

Duke of Swabia Family Tree ................................................................................................. 87<br />

The last Swabians ....................................................................................................................... 88<br />

Enzo .......................................................................................................................................... 88<br />

Manfredi .................................................................................................................................. 88<br />

Frederick of Antioch ............................................................................................................... 88<br />

Corrado Caputo of Antioch ................................................................................................... 89<br />

All Hohenstaufen claims........................................................................................................ 90<br />

Hohenstaufen Family Tree .................................................................................................... 92<br />

HOHENSTAUFEN MILITARY ORDER – “DOMUS SANCTAE MARIAE<br />

THEUTONICORUM” ..................................................................................................................... 94<br />

The Teutonic Order .................................................................................................................... 95<br />

Yearly years of the Teutonic Order .......................................................................................... 97<br />

The Foundation Era 1190-1198 ................................................................................................. 98<br />

Hermann von Salza .................................................................................................................. 101<br />

The Holy Land........................................................................................................................... 103<br />

Decline and fall of the knights. ............................................................................................... 105<br />

The Austrian revival ................................................................................................................. 106<br />

THE ANTIOCH HISTORY .......................................................................................................... 109<br />

History of the Crusades a Holy War ...................................................................................... 110<br />

Prince and titular Princes of Antioch ..................................................................................... 111<br />

First Crusade ............................................................................................................................. 111<br />

Roger I – Count of Sicily (1031-1101) .................................................................................... 114<br />

Norman Kings of Sicily ........................................................................................................... 115<br />

Hohenstaufen Kingdom .......................................................................................................... 115<br />

PRINCIPALITY OF ANTIOCH ................................................................................................... 117<br />

Prince of Antioch ...................................................................................................................... 118<br />

The Dynasty of Frederick of Antioch ..................................................................................... 119<br />

Principality of Antioch enters on Frederick II Emblem ...................................................... 120<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 16 of 200

FREDERICK OF ANTIOCH ........................................................................................................ 124<br />

Maria of Antioch ....................................................................................................................... 125<br />

Prince of Antioch in the Coat of Arms ................................................................................... 129<br />

Count in the kingdom of Sicily ............................................................................................... 131<br />

Origins of the claims of Kingdom of Jerusalem ................................................................... 132<br />

Maria Matilde of Antioch genealogy tree: ............................................................................. 134<br />

..................................................................................................................................................... 134<br />

..................................................................................................................................................... 135<br />

The descendants of Frederick of Antioch .............................................................................. 136<br />

Corrado Caputo prince of Antioch ..................................................................................... 136<br />

Filippa (Philippa) .................................................................................................................. 136<br />

Margherita ............................................................................................................................. 136<br />

Federico prince of Antioch .................................................................................................. 136<br />

Maria ...................................................................................................................................... 136<br />

Kinder ..................................................................................................................................... 136<br />

THE KINGDOM OF SICILY ....................................................................................................... 138<br />

The conquest ............................................................................................................................. 140<br />

Norman Kingdom ..................................................................................................................... 141<br />

Hohenstaufen Kingdom .......................................................................................................... 143<br />

Angevin and Aragonese Kingdom .......................................................................................... 145<br />

The kingdom of Sicily under Aragon and Spain ................................................................... 145<br />

The War of the Spanish Succession ....................................................................................... 146<br />

The two kingdoms under the house of Bourbon .................................................................. 147<br />

Malta under the Knights .......................................................................................................... 147<br />

KINGDOM OF NAPLES .............................................................................................................. 148<br />

Overview ................................................................................................................................ 149<br />

Palazzo Reale di Napoli (Royal Palace of Naples) .................................................................... 151<br />

THE SICILIAN VESPERS ........................................................................................................... 151<br />

The Papacy versus the House of Hohenstaufen ................................................................... 152<br />

Charles of Anjou and Sicilian unrest ..................................................................................... 152<br />

Giovanni da Procida ................................................................................................................. 154<br />

Easter Monday 1292 ................................................................................................................. 154<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 17 of 200

The church of the Holy Spirit in Palermo. ............................................................................ 155<br />

The Aragonese invasion ........................................................................................................... 156<br />

Peter of Sicily ............................................................................................................................. 157<br />

Peter (Pedro) III of Aragon ..................................................................................................... 158<br />

Corrado Caputo prince of Antioch at the Sicilian Vesper ................................................... 160<br />

Death of King of Aragon and Charles of Anjou .................................................................... 162<br />

The Vespers and Europe .......................................................................................................... 163<br />

Charles of Anjou and Sicilian unrest.................................................................................. 165<br />

Saint Luis Day in Sicily ............................................................................................................ 167<br />

Kingdom of Sicily under the Crown of Aragon and Spain .................................. 168<br />

The War of the Spanish Succession ............................................................................. 169<br />

CORRADO CAPUTO PRINCE OF ANTIOCH .......................................................................... 170<br />

Caputo Coat of Arms of Gualtieri and Lorenzo .................................................................... 174<br />

Proof of Corrado of Antioch legitimate descendant of the Hohenstaufen Dynasty<br />

and first bearer of the family name Caputo .......................................................................... 174<br />

Corrado difficult life ................................................................................................................. 175<br />

The Battle of Benevento ........................................................................................................... 176<br />

Corrado of Antioch and Conradin of Swabia and his expedition to Italy ......................... 179<br />

The Battle of Tagliacozzo ......................................................................................................... 182<br />

The End of Corradino Hohenstaufen..................................................................................... 184<br />

Saved the life of Corrado (Caputo) of Antioch ...................................................................... 187<br />

The last days of Corrado of Antioch ....................................................................................... 190<br />

Author personal Coat of Arms ................................................................................................ 192<br />

Authors that wrote about the Caputo Family ....................................................................... 192<br />

Books that refer to Corrado Caputo of Antioch .................................................................... 192<br />

Parentage with Caputo family (until 1665) ................................................................................. 193<br />

Corrado Caputo Genealogy Tree ............................................................................................ 194<br />

......................................................................................................................................................... 195<br />

......................................................................................................................................................... 196<br />

Bibliography .................................................................................................................................... 197<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 18 of 200

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE OF THE<br />

GERMAN NATION<br />

The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation<br />

(Latin: Imperium Romanum Sacrum Nationis<br />

Germanicæ; German: Heiliges Römisches Reich<br />

Deutscher Nation) was traditionally founded on<br />

Christmas Day of the year 800 A.D., when Pope Leo<br />

III placed the crown on the head of Charlemagne in<br />

St. Peter's, and the assembled multitudes shouted<br />

"Carolo Augusto, a Deo coronato magno et pacifico<br />

imperatori, vita et victoria!" — "To Charles the<br />

Magnificent, crowned the great and peace-giving<br />

emperor by God, life and victory!" Strictly speaking,<br />

however, Charles's empire was neither Roman nor<br />

German, but Frankish — or as we might say, a sort of French-German mix (for that<br />

matter, t<strong>here</strong> was a perfectly valid Roman Emperor at the time in any case*). The<br />

Empire was not officially described as "Holy" until the twelfth century, nor<br />

officially "German" before the sixteenth. Charlemagne's empire quickly fell to<br />

pieces among his squabbling successors, and the Holy Roman Emperors<br />

themselves tended to ignore any discontinuity between pagan and Christian Rome<br />

— Frederick I Barbarossa (1123-1190) going so far as to assert that one of his<br />

reasons for going on Crusade was to avenge the defeat of Crassus by the Parthians<br />

(53 B.C.).<br />

Germany as a realm separate from the Frankish empire<br />

emerged with the Treaties of Verdun (843) and Mersen<br />

(870). After the last of Charlemagne's line died in 911, the<br />

German nobles elected Henry the Fowler, Duke of<br />

Saxony, as King of the Germans. The coronation of his<br />

son Otto in 962 may be taken as the actual foundation of<br />

the Holy Roman Empire. The actual term "Holy Roman<br />

Empire" began to be used only during the reign of<br />

Friedrich Barbarossa two centuries and two dynasties<br />

later.<br />

When Conrad III died in 1152, after taking part in the Second Crusade, and was<br />

succeeded, on his own recommendation, by his nephew Frederick, Duke of Swabia,<br />

who reigned as Frederick I, or Frederick Barbarossa /Red Beard). When Pope<br />

Eugene III crowned him in 1155 he added the word "holy" to the name<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 19 of 200

of the empire, making it the Holy Roman Empire, the name by which it was<br />

t<strong>here</strong>after known.<br />

The medieval period of the Empire was dominated by a series of internal struggles<br />

with the powerful German nobility, by struggles with the Italian communes, and<br />

above all, by the great struggle with the Papacy. Notable figures in that contest<br />

include Henry IV, whose famous submission to Pope Gregory VII (Hildebrand) at<br />

Canossa was subsequently reversed by Gregory's exile, and the aforementioned<br />

Frederick I, whose defeat at Legnano led to his submission to Alexander III. The<br />

important point <strong>here</strong> is that the Empire and the Papacy, both competing for secular<br />

and religious power over all Christendom without the means to enforce it,<br />

essentially destroyed each other’s credibility. This was not helped by a fairly<br />

consistent policy of Emperors to neglect the basis of their power in Germany to<br />

grasp at its shadow in Italy - because in order for a German king to become an<br />

Emperor, he had to go to Italy and be crowned by the pope. This worked much to<br />

the advantage of the nationalistic monarchies of France, England and Spain.<br />

The climax was reached with the reign of Friedrich II (1215-<br />

1250), Barbarossa's grandson, who while being an<br />

individual of singular gifts nonetheless attempted to run an<br />

Italian-German Empire from Sicily, but had come to the<br />

throne against his rival Otto IV largely as a consequence of<br />

the victory of King Philip II of France against the armies of<br />

King John of England and Otto at Bouvines. His reign had<br />

some impressive successes (he managed to get<br />

excommunicated for leading a crusade which restored the<br />

"holy places" to Christian pilgrims without anyone getting<br />

killed), but failed to establish a secure power base and got his line targeted by both<br />

the French and the Papacy, insofar as the difference mattered at that point. After<br />

his death and those of his sons, the name of Holy Roman Emperor was an empty<br />

title sought and won by adventurers. After this period, the Interregnum, or in the<br />

words of a German poet, "die kaiserlose, die schreckliche Zeit" (the emperor-less,<br />

terrible time"), the Empire recovered somewhat and for a time its great’s allotted<br />

the crown to the houses of Habsburg, Luxemburg and Wittelsbach by Rota.<br />

Despite its name, the empire had many traits of a confederation, with the German<br />

King (Emperor-elect) being elected by the most powerful regional lords, although it<br />

was only through the Golden Bull of 1356 that it was settled in a legally binding way<br />

who had the right to elect a king. From 1356 t<strong>here</strong> were seven prince electors: the<br />

archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier, the king of Bohemia, the margraves of<br />

Brandenburg and Meissen (Saxony), and the Count Palatine on the Rhine<br />

(Pfalzgraf bei Rhein). This more or less set the tone, but t<strong>here</strong> were several changes<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 20 of 200

over the centuries. For one, the duke of Bavaria would sometimes conspire with the<br />

Count Palatine to exclude Bohemia on the grounds that he wasn't German—but<br />

only when the duke and the Count Palatine weren't squabbling about some family<br />

issue (both were Wittelsbachs). During the Thirty Years' War, the Bavarian<br />

Wittelsbachs got ahold of the Palatinate vote because the Bavarian line were<br />

Catholics and their Palatinate cousins were not; the Palatinate branch got a shiny<br />

new Electorate when the war concluded to maintain balance between Protestants<br />

and Catholics among the electors. However, this new electorate passed to a third,<br />

Catholic branch of the Wittelsbachs, leading to the appointment of a new<br />

Protestant elector, in Brunswick-Lüneburg (known as the Electorate of Hannover<br />

from its capital city; members of this line would find greater success elsew<strong>here</strong>),<br />

although as the Catholic Palatinate Wittelsbachs inherited Bavaria, as well, it<br />

turned out to be a moot point. Finally, Regensburg, Salzburg, Würzburg,<br />

Württemberg, Baden, and Hesse-Kassel were all given electorates in the final years<br />

of the Holy Roman Empire to add to their stature (and in part to replace the four<br />

electorates that had been conquered by the French - Mainz, Trier, Cologne, and the<br />

Palatinate) however, this proved to be a moot point, as the Empire was dissolved a<br />

few years later.<br />

At times, the empire consisted of over 300 sovereign kingdoms, duchies, free cities,<br />

and other entities. In the late 18th century, t<strong>here</strong> were nearly 1800, ranging from<br />

the kingdom of Bohemia to the nominally autonomous territories of Reichsritter<br />

(Imperial knights, i. e. knights subject only to the emperor) and even a handful of<br />

Reichsdörfer (Imperial villages). Unsurprisingly, it often was a total chaos.<br />

Thus throughout most of its history it is rather difficult to define the very borders of<br />

the Holy Roman Empire. Many of the princes owned large territories outside the<br />

Empire or would successfully bid for foreign crowns, such as the rulers of Austria<br />

(also kings of Hungary), Hanover (who became kings of the United Kingdom),<br />

Saxony (two of whom became kings of Poland), and Brandenburg (kings in or of<br />

Prussia since 1701). On the other hand foreign sovereigns came to inherit<br />

territories belonging to the Holy Roman Empire, such as the king of Denmark in<br />

the duchy of Holstein, or conquered them (the kings of Sweden in the Thirty Years<br />

War). Territories that had become de facto independent powers would still<br />

technically considered part of the Empire (as e. g. the Swiss<br />

Confederation and the Republic of the United Netherlands<br />

were until the end of the Thirty Years War).<br />

(Picture: "To God I speak Spanish, to women Italian, to men French, and to<br />

my horse - German."<br />

- Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) Charles was King of Spain from 1516-<br />

1556 and became Holy Roman Emperor from 1519 to 1558).<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 21 of 200

In The Renaissance, despite a brief flourishing under Charles V, the last ruler<br />

actually crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope, the Reformation and the<br />

subsequent Wars of Religion and Thirty Years' War effectively broke the Empire as<br />

a single political unit. T<strong>here</strong>after, the German states ruled themselves and were<br />

able to conclude international treaties as sovereign principalities, and the<br />

Habsburg emperors, though retaining the Imperial title, concentrated more and<br />

more to their Austrian dominions (which included Hungary, parts of Northern Italy<br />

and Southwest Germany, and, since the War of Spanish Succession, the Austrian<br />

Netherlands (most of what is now Belgium plus Luxembourg)). After the War of<br />

Austrian Succession, despite the flourishing of culture under<br />

rulers such as Maria T<strong>here</strong>sa of Austria, Frederick The Great<br />

of Prussia, and Augustus the Strong of Saxony, the empire<br />

was finished. When Emperor Francis II assumed the title<br />

of Emperor Francis I of Austria in 1804 and was forced by<br />

Napoleon to abdicate as Holy Roman Emperor in 1806, the<br />

changed reality was recognized and the Empire came to an<br />

end. Although some German nationalists dreamed of<br />

recreating it following Napoleon's defeat, all they got was the<br />

loose German Federation (Deutscher Bund, 1815-1866).<br />

Though the actual Holy Roman Empire lasted about a thousand years, its depiction<br />

in popular culture is largely a matter of three periods: the time of the Minnesingers,<br />

the time of Albrecht Dürer; and the petty German princedoms of the late<br />

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 22 of 200

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE GUELPHS AND GHIBELLINES<br />

The doctrine of two powers to govern the world, one spiritual and the other<br />

temporal, each independent within its own limits, is as old as Christianity itself,<br />

and based upon the Divine command to "render unto Caesar the things that are<br />

Caesar's and unto God the things that are God's". The earlier popes, such as<br />

Gelasius I (494) and Symmachus (506), wrote emphatically on this theme, which<br />

received illustration in the Christian art of the eighth century in a mosaic of the<br />

Lateran palace that represented Christ delivering the keys to St. Sylvester and the<br />

banner to the Emperor Constantine, and St. Peter giving the papal stole to Leo III<br />

and the banner to Charlemagne. The latter scene insists on the papal action in the<br />

restoration of the Western Empire, which Dante regarded as an act of usurpation<br />

on the part of Leo. For Dante, pope and emperor are as two suns to shed light upon<br />

man's spiritual and temporal paths respectively, divinely ordained by the infinite<br />

goodness of Him from whom the power of Peter and of Caesar bifurcates as from a<br />

point. Thus, throughout the troubled period of the Middle Ages, men inevitably<br />

looked to the harmonious alliance of these two powers to renovate the face of the<br />

earth, or, when it seemed no longer possible for the two to work in unison, they<br />

appealed to one or the other to come forward as the savior of society. We get the<br />

noblest form of these aspirations in the ideal imperialism of Dante's "De<br />

Monarchia", on the one hand; and, on the other, in the conception of the ideal<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 23 of 200

pope, the papa angelico of St. Bernard's "De Consideratione" and the "Letters" of<br />

St. Catherine of Siena.<br />

This great conception can vaguely be discerned at the back of the nobler phases of<br />

the Guelph and Ghibelline contests, but it was soon obscured by considerations and<br />

conditions absolutely non-idealistic and material. Two main factors may be said to<br />

have produced and kept alive these struggles: the antagonism between the papacy<br />

and the empire, each endeavoring to extend its authority into the field of the other;<br />

the mutual hostility between a territorial feudal nobility, of military instincts, and<br />

of foreign descent, and a commercial and municipal democracy, clinging to the<br />

traditions of Roman law, and ever increasing in wealth and power. Since the<br />

coronation of Charlemagne (800), the relations of Church and State had been illdefined,<br />

full of the seeds of future contentions, which afterwards bore fruit in the<br />

prolonged "War of Investitures", begun by Pope Gregory VII and the Emperor<br />

Henry IV (1075), and brought to a close by Callistus II and Henry V (1122). Neither<br />

the Church nor the Empire was able to make itself politically supreme in Italy.<br />

Throughout the eleventh century, the free Italian communes had arisen, owing a<br />

nominal allegiance to the Empire as having succeeded to the power of ancient<br />

Rome and as being the sole source of law and right, but looking for support,<br />

politically as well as spiritually, to the papacy.<br />

The names "Guelph" and "Ghibelline" appear to have originated in Germany, in the<br />

rivalry between the house of Welf (Dukes of Bavaria) and the house of<br />

Hohenstaufen (Dukes of Swabia), whose ancestral castle was Waiblingen in<br />

Franconia. Agnes, daughter of Henry IV and sister of Henry V, married Duke<br />

Frederick of Swabia. "Welf" and "Waiblingen" were first used as rallying cries at the<br />

battle of Weinsberg (1140), w<strong>here</strong> Frederick's son, Emperor Conrad III (1138-1152),<br />

defeated Welf, the brother of the rebellious Duke of Bavaria, Henry the Proud.<br />

Conrad's nephew and successor, Frederick I "Barbarossa" (1152-1190), attempted<br />

to reassert the imperial authority over the Italian cities, and to exercise supremacy<br />

over the papacy itself. He recognized an antipope, Victor, in opposition to the<br />

legitimate sovereign pontiff, Alexander III (1159), and destroyed Milan (1162), but<br />

was thoroughly defeated by the forces of the Lombard League at the battle of<br />

Legnano (1176) and compelled to agree to the peace of Constance (1183), by which<br />

the liberties of the Italian communes were secured. The mutual jealousies of the<br />

Italian cities themselves, however, prevented the treaty from having permanent<br />

results for the independence and unity of the nation. After the death of Frederick's<br />

son and successor, Henry VI (1197), a struggle ensued in Germany and in Italy<br />

between the rival claimants for the Empire, Henry's brother, Philip of Swabia (d.<br />

1208), and Otto of Bavaria. According to the more probable theory, it was then that<br />

the names of the factions were introduced into Italy. "Guelfo" and "Ghibellino"<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 24 of 200

eing the Italian forms of "Welf" and "Waiblingen". The princes of the house of<br />

Hohenstaufen being the constant opponents of the papacy, "Guelph" and<br />

"Ghibelline" were taken to denote ad<strong>here</strong>nts of Church and Empire, respectively.<br />

The popes having favored and fostered the growth of the communes, the Guelphs<br />

were in the main the republican, commercial, burgher party; the Ghibellines<br />

represented the old feudal aristocracy of Italy. For the most part the latter were<br />

descended from Teutonic families planted in the peninsula by the Germanic<br />

invasions of the past, and they naturally looked to the emperors as their protectors<br />

against the growing power and pretensions of the cities. It is, however, clear that<br />

these names were merely adopted to designate parties that, in one form or another,<br />

had existed from the end of the 11 C.<br />

In the endeavor to realize the precise significance of these terms, one must consider<br />

the local politics and the special conditions of each individual state and town. Thus,<br />

in Florence, a family quarrel between the Buondelmonti and the Amidei, in 1215,<br />

led traditionally to the introduction of "Guelph" and "Ghibelline" to mark off the<br />

two parties that henceforth kept the city divided, but the factions themselves had<br />

existed virtually since the death of the great Countess Mathilda of Tuscany (1115), a<br />

hundred years before, had left the republic at liberty to work out its own destinies.<br />

The rivalry of city against city was also, in many cases, a more potent inducement<br />

for one to declare itself Guelph and another Ghibelline, than any specially papal or<br />

imperial proclivities on the part of its citizens. Pavia was Ghibelline, because Milan<br />

was Guelph. Florence being the head of the Guelph league in Tuscany, Lucca was<br />

Guelph because it needed Florentine protection; Siena was Ghibelline, because it<br />

sought the support of the emperor against the Florentines and against the<br />

rebellious nobles of its own territory; Pisa was Ghibelline, partly from hostility to<br />

Florence, partly from the hope of rivaling with imperial aid the maritime glories of<br />

Genoa. In many cities a Guelph faction and a Ghibelline faction alternately got the<br />

upper hand, drove out its adversaries, destroyed their houses and confiscated their<br />

possessions. Venice, which had aided Alexander III against Frederick I, owed no<br />

allegiance to the Western empire, and naturally stood apart.<br />

One of the last acts of Frederick I had been to secure the marriage of his son Henry<br />

with Constance, aunt and heiress of William the Good, the last of the Norman kings<br />

of Naples and Sicily. The son of this marriage, Frederick II (b. 1194), thus inherited<br />

this South Italian kingdom, hitherto a bulwark against the imperial Germanic<br />

power in Italy, and was defended in his possession of it against the Emperor Otto<br />

by Pope Innocent III, to whose charge he had been left as a ward by his mother. On<br />

the death of Otto (1218), Frederick became emperor, and was crowned in Rome by<br />

Honorius III (1220). The danger, to the papacy and to Italy alike, of the union of<br />

Naples and Sicily (a vassal kingdom of the Holy See) with the empire, was obvious;<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 25 of 200

and Frederick, when elected King of the Romans, had sworn not to unite the<br />

southern kingdom with the German crown. His neglect of this pledge, together with<br />

the misunderstandings concerning his crusade, speedily brought about a fresh<br />

conflict between the Empire and the Church. The prolonged struggle carried on by<br />

the successors of Honorius, from Gregory IX to Clement IV, against the last<br />

Swabian princes, mingled with the worst excesses of the Italian factions on either<br />

side, is the central and most typical phase of the Guelph and Ghibelline story.<br />

From 1227, when first excommunicated by Gregory IX, to the end of his life,<br />

Frederick had to battle incessantly with the popes, the second Lombard League,<br />

and the Guelph party in general throughout Italy. The Genoese fleet, conveying the<br />

French cardinals and prelates to a council summoned at Rome, was destroyed by<br />

the Pisans at the battle of Meloria (1241); and Gregory's successor, Innocent IV,<br />

was compelled to take refuge in France (1245). The atrocious tyrant, Ezzelino da<br />

Romano, rose up a bloody despotism in Verona and Padua; the Guelph nobles were<br />

temporarily expelled from Florence; but Frederick's favorite son, King Enzo of<br />

Sardinia, was defeated and captured by the Bolognese (1249), and the strenuous<br />

opposition of the Italians proved too much for the imperial power. After the death<br />

of Frederick (1250), it seemed as if his illegitimate son, Manfred, King of Naples<br />

and Sicily (1254-1266), himself practically an Italian, was about to unite all Italy<br />

into a Ghibelline, anti-papal monarchy.<br />

Although in the north the Ghibelline supremacy was checked by the victory of the<br />

Marquis Azzo d'Este over Ezzelino at Cassano on the Adda (1259), in Tuscany even<br />

Florence was lost to the Guelph cause by the sanguinary battle of Montaperti (4<br />

Sept., 1260), celebrated in Dante's poem. Urban IV then offered Manfred's crown<br />

to Charles of Anjou, the brother of St. Louis of France. Charles came to Italy, and<br />

by the great victory of Benevento (26 Feb., 1266), at which Manfred was killed,<br />

established a French dynasty on the throne of Naples and Sicily. The defeat of<br />

Frederick's grandson, Conradin, at the battle of Tagliacozzo (1268) followed by his<br />

judicial murder at Naples by the command of Charles, marks the end of the<br />

struggle and the overthrow of the German imperial power in Italy for two and a half<br />

centuries.<br />

Thus the struggle ended in the complete triumph of the Guelphs. Florence, once<br />

more free and democratic, had established a special Organisation within the<br />

republic, known as the Parte Guelfa, to maintain Guelph principles and chastise<br />

supposed Ghibellines. Sienna, hitherto the stronghold of Ghibellinism in Tuscany,<br />

became Guelph after the battle of Colle di Valdelsa (1269). The pontificate of the<br />

saintly and pacific Gregory X (1271-1276) tended to dissociate the Church from the<br />

Guelph party, which now began to look more to the royal house of France.<br />

Although they lost Sicily by the "Vespers of Palermo" (1282), the Angevin kings of<br />

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty - Page 26 of 200

Naples remained the chief power in Italy, and the natural leaders of the Guelphs,<br />

with whose aid they had won their crown.<br />

Ad<strong>here</strong>nce to Ghibelline principles was still maintained by the republics of Pisa and<br />

Arezzo, the Della Scala family at Verona, and a few petty despots <strong>here</strong> and t<strong>here</strong> in<br />

Romagna and elsew<strong>here</strong>. No great ideals of any kind were by this time at stake. As<br />

Dante declares in the "Paradiso" (canto VI), one party opposed to the imperial<br />

eagle the golden lilies, and the other appropriated the eagle to a faction, "so that it<br />

is hard to see which sinned most". The intervention of Boniface VIII in the politics<br />

of Tuscany, when the predominant Guelphs of Florence split into two new factions,<br />

was the cause of Dante's exile (1301), and drove him for a while into the ranks of<br />

the Ghibellines. The next pope, Benedict XI (1303-1304), made earnest attempts to<br />

reconcile all parties; but the "Babylonian Captivity" of his successors at Avignon<br />

augmented the divisions of Italy.<br />