Diagnosis and management of early- and late-onset cerebellar ataxia

Diagnosis and management of early- and late-onset cerebellar ataxia

Diagnosis and management of early- and late-onset cerebellar ataxia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

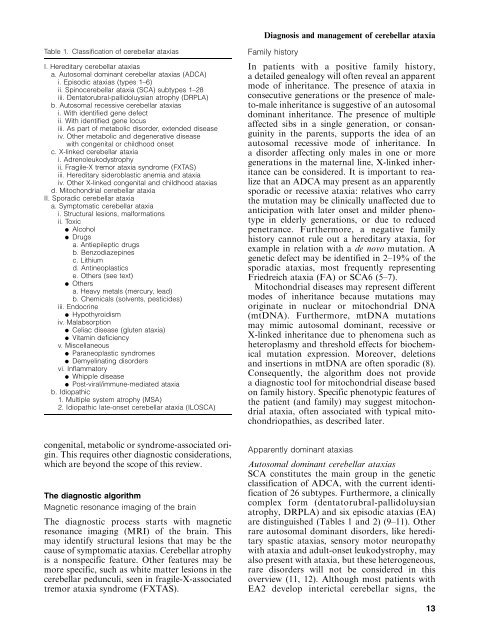

Table 1. Classification <strong>of</strong> <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong>s<br />

I. Hereditary <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong>s<br />

a. Autosomal dominant <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong>s (ADCA)<br />

i. Episodic <strong>ataxia</strong>s (types 1–6)<br />

ii. Spino<strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong> (SCA) subtypes 1–28<br />

iii. Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA)<br />

b. Autosomal recessive <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong>s<br />

i. With identified gene defect<br />

ii. With identified gene locus<br />

iii. As part <strong>of</strong> metabolic disorder, extended disease<br />

iv. Other metabolic <strong>and</strong> degenerative disease<br />

with congenital or childhood <strong>onset</strong><br />

c. X-linked <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

i. Adrenoleukodystrophy<br />

ii. Fragile-X tremor <strong>ataxia</strong> syndrome (FXTAS)<br />

iii. Hereditary sideroblastic anemia <strong>and</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

iv. Other X-linked congenital <strong>and</strong> childhood <strong>ataxia</strong>s<br />

d. Mitochondrial <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

II. Sporadic <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

a. Symptomatic <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

i. Structural lesions, malformations<br />

ii. Toxic<br />

d Alcohol<br />

d Drugs<br />

a. Antiepileptic drugs<br />

b. Benzodiazepines<br />

c. Lithium<br />

d. Antineoplastics<br />

e. Others (see text)<br />

d Others<br />

a. Heavy metals (mercury, lead)<br />

b. Chemicals (solvents, pesticides)<br />

iii. Endocrine<br />

d Hypothyroidism<br />

iv. Malabsorption<br />

d Celiac disease (gluten <strong>ataxia</strong>)<br />

d Vitamin deficiency<br />

v. Miscellaneous<br />

d Paraneoplastic syndromes<br />

d Demyelinating disorders<br />

vi. Inflammatory<br />

d Whipple disease<br />

d Post-viral/immune-mediated <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

b. Idiopathic<br />

1. Multiple system atrophy (MSA)<br />

2. Idiopathic <strong>late</strong>-<strong>onset</strong> <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong> (ILOSCA)<br />

congenital, metabolic or syndrome-associated origin.<br />

This requires other diagnostic considerations,<br />

which are beyond the scope <strong>of</strong> this review.<br />

The diagnostic algorithm<br />

Magnetic resonance imaging <strong>of</strong> the brain<br />

The diagnostic process starts with magnetic<br />

resonance imaging (MRI) <strong>of</strong> the brain. This<br />

may identify structural lesions that may be the<br />

cause <strong>of</strong> symptomatic <strong>ataxia</strong>s. Cerebellar atrophy<br />

is a nonspecific feature. Other features may be<br />

more specific, such as white matter lesions in the<br />

<strong>cerebellar</strong> pedunculi, seen in fragile-X-associated<br />

tremor <strong>ataxia</strong> syndrome (FXTAS).<br />

<strong>Diagnosis</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong><br />

Family history<br />

In patients with a positive family history,<br />

a detailed genealogy will <strong>of</strong>ten reveal an apparent<br />

mode <strong>of</strong> inheritance. The presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong> in<br />

consecutive generations or the presence <strong>of</strong> maleto-male<br />

inheritance is suggestive <strong>of</strong> an autosomal<br />

dominant inheritance. The presence <strong>of</strong> multiple<br />

affected sibs in a single generation, or consanguinity<br />

in the parents, supports the idea <strong>of</strong> an<br />

autosomal recessive mode <strong>of</strong> inheritance. In<br />

a disorder affecting only males in one or more<br />

generations in the maternal line, X-linked inheritance<br />

can be considered. It is important to realize<br />

that an ADCA may present as an apparently<br />

sporadic or recessive <strong>ataxia</strong>: relatives who carry<br />

the mutation may be clinically unaffected due to<br />

anticipation with <strong>late</strong>r <strong>onset</strong> <strong>and</strong> milder phenotype<br />

in elderly generations, or due to reduced<br />

penetrance. Furthermore, a negative family<br />

history cannot rule out a hereditary <strong>ataxia</strong>, for<br />

example in relation with a de novo mutation. A<br />

genetic defect may be identified in 2–19% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

sporadic <strong>ataxia</strong>s, most frequently representing<br />

Friedreich <strong>ataxia</strong> (FA) or SCA6 (5–7).<br />

Mitochondrial diseases may represent different<br />

modes <strong>of</strong> inheritance because mutations may<br />

originate in nuclear or mitochondrial DNA<br />

(mtDNA). Furthermore, mtDNA mutations<br />

may mimic autosomal dominant, recessive or<br />

X-linked inheritance due to phenomena such as<br />

heteroplasmy <strong>and</strong> threshold effects for biochemical<br />

mutation expression. Moreover, deletions<br />

<strong>and</strong> insertions in mtDNA are <strong>of</strong>ten sporadic (8).<br />

Consequently, the algorithm does not provide<br />

a diagnostic tool for mitochondrial disease based<br />

on family history. Specific phenotypic features <strong>of</strong><br />

the patient (<strong>and</strong> family) may suggest mitochondrial<br />

<strong>ataxia</strong>, <strong>of</strong>ten associated with typical mitochondriopathies,<br />

as described <strong>late</strong>r.<br />

Apparently dominant <strong>ataxia</strong>s<br />

Autosomal dominant <strong>cerebellar</strong> <strong>ataxia</strong>s<br />

SCA constitutes the main group in the genetic<br />

classification <strong>of</strong> ADCA, with the current identification<br />

<strong>of</strong> 26 subtypes. Furthermore, a clinically<br />

complex form (dentatorubral-pallidoluysian<br />

atrophy, DRPLA) <strong>and</strong> six episodic <strong>ataxia</strong>s (EA)<br />

are distinguished (Tables 1 <strong>and</strong> 2) (9–11). Other<br />

rare autosomal dominant disorders, like hereditary<br />

spastic <strong>ataxia</strong>s, sensory motor neuropathy<br />

with <strong>ataxia</strong> <strong>and</strong> adult-<strong>onset</strong> leukodystrophy, may<br />

also present with <strong>ataxia</strong>, but these heterogeneous,<br />

rare disorders will not be considered in this<br />

overview (11, 12). Although most patients with<br />

EA2 develop interictal <strong>cerebellar</strong> signs, the<br />

13