On irregular polysemy* Gergely Pethő

On irregular polysemy* Gergely Pethő

On irregular polysemy* Gergely Pethő

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2.2.2. Second example: the polysemy ‘body part’ – ‘part of clothing that covers<br />

it’<br />

Our second example will illustrate that a previously presumably productive polysemy<br />

type that could be derived by a shifting rule can “fall apart” because several words belonging<br />

to it are lexicalised for a more specific, non-predictable use. This may have<br />

happened with the polysemy ‘body part’ – ‘part of clothing that covers it’ in Hungarian,<br />

which may have been productive.<br />

Words that belong to this polysemy type behave in a way that can be derived by<br />

an appropriate shifting rule that conforms to the following schema:<br />

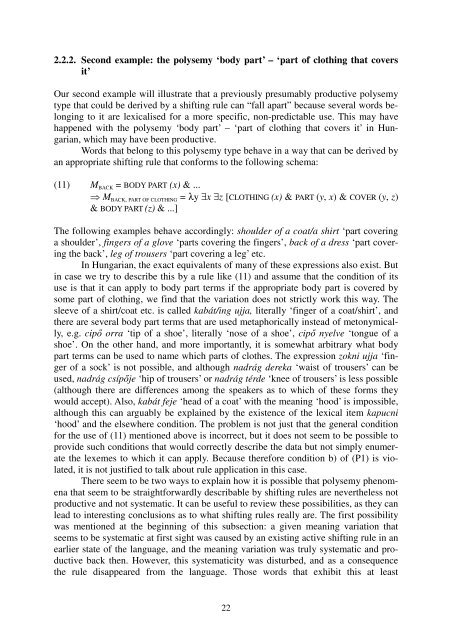

(11) M BACK = BODY PART (x) & ...<br />

⇒ M BACK, PART OF CLOTHING = λy ∃x ∃z [CLOTHING (x) & PART (y, x) & COVER (y, z)<br />

& BODY PART (z) & ...]<br />

The following examples behave accordingly: shoulder of a coat/a shirt ‘part covering<br />

a shoulder’, fingers of a glove ‘parts covering the fingers’, back of a dress ‘part covering<br />

the back’, leg of trousers ‘part covering a leg’ etc.<br />

In Hungarian, the exact equivalents of many of these expressions also exist. But<br />

in case we try to describe this by a rule like (11) and assume that the condition of its<br />

use is that it can apply to body part terms if the appropriate body part is covered by<br />

some part of clothing, we find that the variation does not strictly work this way. The<br />

sleeve of a shirt/coat etc. is called kabát/ing ujja, literally ‘finger of a coat/shirt’, and<br />

there are several body part terms that are used metaphorically instead of metonymically,<br />

e.g. cipő orra ‘tip of a shoe’, literally ‘nose of a shoe’, cipő nyelve ‘tongue of a<br />

shoe’. <strong>On</strong> the other hand, and more importantly, it is somewhat arbitrary what body<br />

part terms can be used to name which parts of clothes. The expression zokni ujja ‘finger<br />

of a sock’ is not possible, and although nadrág dereka ‘waist of trousers’ can be<br />

used, nadrág csípője ‘hip of trousers’ or nadrág térde ‘knee of trousers’ is less possible<br />

(although there are differences among the speakers as to which of these forms they<br />

would accept). Also, kabát feje ‘head of a coat’ with the meaning ‘hood’ is impossible,<br />

although this can arguably be explained by the existence of the lexical item kapucni<br />

‘hood’ and the elsewhere condition. The problem is not just that the general condition<br />

for the use of (11) mentioned above is incorrect, but it does not seem to be possible to<br />

provide such conditions that would correctly describe the data but not simply enumerate<br />

the lexemes to which it can apply. Because therefore condition b) of (P1) is violated,<br />

it is not justified to talk about rule application in this case.<br />

There seem to be two ways to explain how it is possible that polysemy phenomena<br />

that seem to be straightforwardly describable by shifting rules are nevertheless not<br />

productive and not systematic. It can be useful to review these possibilities, as they can<br />

lead to interesting conclusions as to what shifting rules really are. The first possibility<br />

was mentioned at the beginning of this subsection: a given meaning variation that<br />

seems to be systematic at first sight was caused by an existing active shifting rule in an<br />

earlier state of the language, and the meaning variation was truly systematic and productive<br />

back then. However, this systematicity was disturbed, and as a consequence<br />

the rule disappeared from the language. Those words that exhibit this at least<br />

22