The National Liberal Immigration League and Immigration Restriction,

The National Liberal Immigration League and Immigration Restriction,

The National Liberal Immigration League and Immigration Restriction,

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>Restriction</strong>,<br />

Rivka Shpak Lissak<br />

Between the years 1896 <strong>and</strong> 1917, as concern about the flow of<br />

immigrants from southern <strong>and</strong> eastern Europe mounted, immi-<br />

gration restriction became a public issue in the United States. <strong>The</strong><br />

traditional principle of free immigration was now challenged on<br />

both socioeconomic <strong>and</strong> ethnic-cultural grounds, <strong>and</strong> became<br />

entangled with a web of social <strong>and</strong> industrial problems, among<br />

them unemployment, working conditions, low wages, <strong>and</strong> trade<br />

unionism. Conflicting versions of what it meant to be an American<br />

<strong>and</strong> differences regarding the role in the country's development to<br />

be accorded to the newcomers <strong>and</strong> their cultures also formed part<br />

of the controversy.<br />

Over the years since, American scholars have devoted far more<br />

attention to the proponents of immigration restriction <strong>and</strong> the eth-<br />

nic-cultural or nativist philosophy behind it than to its socioeco-<br />

nomic aspect. In particular, they have neglected the struggle<br />

against the restriction of immigration <strong>and</strong> the role played in it by<br />

both immigrants <strong>and</strong> native-born Americans. This paper concen-<br />

trates on the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> (NLIL), <strong>and</strong> its<br />

role in the struggle against restriction during the years 1906-1917.'<br />

Asylum <strong>and</strong> Free <strong>Immigration</strong><br />

America's immigration policy was traditionally governed by two<br />

ideas, the right of asylum <strong>and</strong> free immigration. <strong>The</strong> notion of<br />

America as an asylum had its roots in the earliest years of the colo-<br />

nial era, but it was first put into writing during the Revolutionary<br />

War by Thomas Paine, who said in Common Sense that "this New<br />

World had been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil <strong>and</strong><br />

religious liberty from every part of Europe." Put this way, the idea<br />

was mainly an expression of sympathy for religious dissenters, not<br />

necessarily Catholics or Jews, <strong>and</strong> for rebels against European<br />

tyranny. It implied that political asylum would be given to oppo-

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 199<br />

nents of unjust authority, based upon the right of popular revolt<br />

against tyranny. Some later interpreters emphasized economic<br />

opportunity as an essential component of the asylum idea. Jean de<br />

Crevecoeur wrote in his Letters from an American Farmer: "In this<br />

great American asylum, the poor of Europe have by some means<br />

met together."'<br />

Although there was some disagreement in the nineteenth centu-<br />

ry as to the content or meaning of the right of asylum, govern-<br />

mental circles unequivocally linked economic opportunity with<br />

the idea of free immigration.3 <strong>The</strong> idea of free immigration was<br />

also rooted in the American concept of nationalism. Committed to<br />

the principles of democracy, Americans pledged to accept immi-<br />

grants as equals. Equality involved the recognition that all human<br />

beings were born equal <strong>and</strong> were worthy of joining the American<br />

nation <strong>and</strong> sharing the rights of citizenship. It also implied confi-<br />

dence in the capacity of every human being for change, adapta-<br />

tion, <strong>and</strong> adjustment to the American environment. Above all, the<br />

American tradition was based on the belief that national unity did<br />

not have to rely on common blood.4<br />

Consequently, the idea of free immigration, as distinct from the<br />

right of asylum, was the major underlying assumption upon<br />

which American immigration policy was established. This idea, as<br />

first enunciated by Thomas Jefferson, was based upon the princi-<br />

ple of "natural rights." Thus, a resolution of Congress of July 27,<br />

1868 declared the right of expatriation to be "a natural <strong>and</strong> inher-<br />

ent right of all people, indispensable to the enjoyment of the rights<br />

of life, liberty <strong>and</strong> the pursuit of happiness."'<br />

At the time of the establishment of the Republic, Congress had<br />

chosen not to exercise its authority in this field, <strong>and</strong> the adminis-<br />

tration of immigration was under state rather than federal juris-<br />

diction. This situation changed in 1875, when immigration policy<br />

<strong>and</strong> its administration came under the jurisdiction of Congress <strong>and</strong><br />

the federal government. With the development of the policy of<br />

selection <strong>and</strong> exclusion, Congress demonstrated its sympathy with<br />

victims of political <strong>and</strong> religious persecution by deciding to waive<br />

the restrictions on immigration for the benefit of refugees from<br />

such persecution. It thus defined the right of asylum in political

200 American Jewish Archives<br />

<strong>and</strong> religious terms. Indeed, the <strong>Immigration</strong> Acts of 1875, 1882,<br />

1891, <strong>and</strong> 1907, which denied admission to convicts <strong>and</strong> criminals,<br />

specifically excluded "persons convicted of political offence" from<br />

the incidence of the laws. Similarly, the <strong>Immigration</strong> Act of 1907, in<br />

relation to the "public charge clause," allowed aliens to enter <strong>and</strong><br />

remain in the country even if they were destitute or unable to earn<br />

a living, in cases where they were fleeing for their lives or trying to<br />

avoid persecution on political or religious grounds. Significantly,<br />

anarchists were not included in the category of political refugee^.^<br />

Contemporary data show that the distinction between the right<br />

of asylum <strong>and</strong> the right of free immigration, namely, the distinction<br />

between refugees <strong>and</strong> immigrants, was widely accepted at the<br />

turn of the century by both advocates <strong>and</strong> opponents of free immigrati~n.~<br />

In this respect, the results obtained in the 1914 poll of college<br />

<strong>and</strong> university professors conducted by the foreign press<br />

committee of the American Jewish Committee were quite typical.<br />

Asked whether they favored further restrictions on immigration<br />

<strong>and</strong> whether literacy tests should be imposed to determine the<br />

desirability of immigrants or only of those who were political <strong>and</strong><br />

religious refugees, the majority of the respondents, regardless of<br />

their views on immigration policy, saw immigrants <strong>and</strong> refugees<br />

as separate categories?<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Restriction</strong> Controversy<br />

Several organizations were deeply involved in the struggle for <strong>and</strong><br />

against immigration restriction. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>Restriction</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong> (IRL), founded in Boston in 1894, devoted itself to the<br />

cause of immigration restriction, engaging in legislative lobbying<br />

in Washington <strong>and</strong> propag<strong>and</strong>a campaigns throughout the coun-<br />

try with the aim of enlisting mass support for immigration restric-<br />

tion. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong>'s leaders regarded the "new immigration" as the<br />

principal cause of the country's social, economic, <strong>and</strong> political<br />

problems, due to the differences in race, culture, <strong>and</strong> tradition<br />

between the "new immigrants" <strong>and</strong> native-born Americans. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong> adopted socioeconomic as well as racial-cultural argu-<br />

ments in its campaign for restriction <strong>and</strong> lobbied for a literacy test<br />

as the best method for implementing its policy of restriction. <strong>The</strong>

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 201<br />

IRL also sought, especially after 1911, to eliminate the right of asy-<br />

lum from American law. It argued that since the <strong>Immigration</strong><br />

Commission, established by Congress in 1907, had stated in its<br />

report that the present immigrants were arriving in the country<br />

with the aim of improving their economic conditions, the policy of<br />

admission should be decided on the basis of socioeconomic con-<br />

siderations alone.9<br />

<strong>The</strong> American Federation of Labor (AFL), the country's largest<br />

labor union, was another leading participant in the campaign for<br />

immigration restriction, especially after 1906. At its annual con-<br />

vention of 1909, the AFL adopted a resolution in favor of immi-<br />

gration restriction by means of a literacy test "for restricting the<br />

present stimulated influx of cheap labor, whose competition is so<br />

ruinous to workers already here, whether native or foreign."<br />

Although it emphasized the economic issue, the AFL shared the<br />

IRL's view that immigrants were inassimilable <strong>and</strong> therefore a<br />

threat to American institutions. <strong>The</strong> AFL joined the IRL in calling<br />

for a literacy test, considering it a tariff measure against the com-<br />

petition of foreign labor. However, unlike the IRL, the AFL<br />

endorsed the right of asylum.'"<br />

<strong>The</strong> huge immigration <strong>and</strong> the many problems it created<br />

spawned a number of voluntary organizations designed to help<br />

immigrants adjust to life in America. Established by civic-minded<br />

citizens <strong>and</strong> funded by contributions, these organizations met<br />

newcomers on arrival, ran labor, welfare, <strong>and</strong> legal-advice<br />

bureaus, <strong>and</strong> conducted classes in English <strong>and</strong> civics. <strong>The</strong>y also<br />

lobbied for legislation to protect newcomers against exploitation<br />

<strong>and</strong> fraud. <strong>The</strong> best-known of these organizations were the North<br />

American Civic <strong>League</strong> for immigrants, founded in Boston in 1909<br />

with branches throughout the country; the Committee for<br />

Immigrants in America, formerly a branch of the NACL, founded<br />

in New York in 19x4; <strong>and</strong> the Immigrants' Protective <strong>League</strong> of<br />

Chicago. Since all of these organizations had been set up to help<br />

immigrants after their arrival in America, they were not concerned<br />

with immigration policy as such. With the exception of the<br />

Immigrants' Protective <strong>League</strong> of Chicago, which was committed<br />

to defending the right of asylum, they took no st<strong>and</strong> one way or

Louis Edward Levy<br />

(7846-1919)

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 203<br />

the other on the question of restriction.ll<br />

<strong>The</strong> Society of the Friends of Russian Freedom (FRF) was found-<br />

ed in 1906 to rally public opinion in favor of a representative gov-<br />

ernment in Russia, but it also actively defended the right of asylum<br />

for Russian political refugees. It counted among its sponsors many<br />

prominent liberals, including Jane Addams, Norman Hapgood,<br />

Oswald Garrison Villard, Lillian D. Wald, Dr. Lyman Abbott, <strong>and</strong><br />

Samuel Gompers. <strong>The</strong> Political Refugees Defence <strong>League</strong> (PRDL),<br />

founded in 1909 by a group of Socialists with some liberal backing,<br />

also defended the right of asylum.12<br />

<strong>Liberal</strong> Progressives played an important role in helping new-<br />

comers to adjust to their new country through these organizations,<br />

as well as their own voluntary groups. <strong>The</strong> most important work<br />

in this area was done by the settlement movement, established at<br />

the turn of the century by a group of upper-middle-class men <strong>and</strong><br />

women who went to live in the slums of America's cities in order<br />

to deal with the problems of the working class. Once there, the set-<br />

tlement workers soon realized that the working class consisted<br />

mostly of immigrants, <strong>and</strong> that the newest arrivals, apart from<br />

their problems as industrial workers (mostly unskilled), had the<br />

additional burden of social <strong>and</strong> cultural adjustment to the<br />

American environment. Thus, settlement workers devoted them-<br />

selves to helping the newcomers cope with these two problems.'3<br />

<strong>The</strong> uniqueness of the liberal wing of the Progressive move-<br />

ment-historians have variously called it social, humanitarian, or<br />

advanced progressivism-lay in its more comprehensive interpre-<br />

tation of democracy. <strong>The</strong>y sought to extend the idea of political<br />

democracy, on which there was an American consensus, by sug-<br />

gesting new measures for coping with the ever-sharper class divi-<br />

sions in the country's emerging urban centers.14<br />

With this goal in mind, <strong>Liberal</strong> Progressives developed the idea<br />

of social democracy as an inevitable stage in the evolution <strong>and</strong><br />

progress of society toward full democracy. Laissez-faire was to be<br />

modified by social welfare legislation. <strong>The</strong> government was to take<br />

responsibility for the underprivileged, improving their living <strong>and</strong><br />

working conditions <strong>and</strong> providing better educational opportuni-<br />

ties. To achieve these goals, several organizations were formed,

204 American Jewish Archives<br />

among them the American Association for Labor Legislation<br />

(AALL) .'5<br />

<strong>Liberal</strong> Progressives became closely involved in the industrial<br />

situation, supporting the right of workers to organize unions <strong>and</strong><br />

engage in collective bargaining. This support, which was the outgrowth<br />

of their commitment to the well-being of the underprivileged,<br />

created a close relationship <strong>and</strong> active cooperation between<br />

Progressives <strong>and</strong> the labor movement. <strong>The</strong>y were seriously concerned<br />

about the problems faced by unskilled workers, very many<br />

of whom were new immigrants. With growing awareness that the<br />

unskilled were victims of industrial exploitation, they gradually<br />

became convinced of the need for an Industrial Minimums<br />

Legislation Program, of which a statutory minimum wage would<br />

be a major component. <strong>The</strong>y were greatly disturbed by the fact that<br />

unskilled workers were not generally unionized by the AFL,<br />

which was primarily a craft-union federation. <strong>The</strong>y were also troubled<br />

by the AFL's refusal to support a minimum wage law for<br />

unskilled workers as part of the Industrial Minimums Legislation<br />

Program, which it endorsed, on the ground that such legislation<br />

would weaken the bargaining power of the unions. <strong>The</strong> AFL considered<br />

unskilled immigrants to be competitors, <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>ed<br />

that their admission to the country be restricted. <strong>Liberal</strong><br />

Progressives never challenged the view that the state had the right<br />

to restrict immigration-excluding the right of asylum-if the wellbeing<br />

of its citizens was at stake. <strong>The</strong> differences of opinion, both<br />

among themselves <strong>and</strong> with labor leaders, focused rather on<br />

whether immigration indeed affected the general welfare of the<br />

American working class <strong>and</strong> whether immigration restriction was<br />

needed, on socioeconomic grounds, to protect American laborers.16<br />

<strong>The</strong> settlement movement never reached a consensus on the place<br />

new immigrants <strong>and</strong> their cultures should occupy in America.'7<br />

Nevertheless, its members took upon themselves the task of educating<br />

<strong>and</strong> socializing newcomers. For this end they organized clubs<br />

<strong>and</strong> initiated cultural <strong>and</strong> educational programs, including classes<br />

in English <strong>and</strong> civics, to introduce them to American society, inculcate<br />

them with American norms of behavior, <strong>and</strong> teach them<br />

American ways of doing things.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 205<br />

<strong>Liberal</strong> Progressives shared the American consensus on the dis-<br />

tinction between the right of asylum <strong>and</strong> free immigration. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were united in their support of the right of asylum, but divided on<br />

the issue of free immigration in both its ethnic-cultural <strong>and</strong> socioe-<br />

conomic aspects.<br />

By the end of the nineteenth century, America's business com-<br />

munity had developed an ambivalent approach toward immigra-<br />

tion. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, immigration was considered good for busi-<br />

ness because immigrant labor was needed to increase the output of<br />

mines, for the construction of railroads, <strong>and</strong> for industrial expan-<br />

sion. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, the radical elements among the immi-<br />

grants jeopardized social stability <strong>and</strong> industrial relations between<br />

capital <strong>and</strong> labor in periods of unemployment <strong>and</strong> economic<br />

depression. <strong>Immigration</strong> also increased the financial burden on<br />

charitable organizations <strong>and</strong> the community. During the last quar-<br />

ter of the nineteenth century <strong>and</strong> the first decade of the twentieth,<br />

northern businessmen, acting in their own interests, took advan-<br />

tage of the "diversity <strong>and</strong> tensions among the many peoples of<br />

southern <strong>and</strong> eastern Europe" <strong>and</strong> organized labor, thereby to<br />

exploit cheap, nonunionized immigrant workers. Southern busi-<br />

nessmen, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, made efforts to attract immigrant<br />

labor to the South in order to develop its economy. This attitude<br />

became ambivalent during the second decade of the new century,<br />

as the result of the anti-foreign, anti-Catholic, <strong>and</strong> anti-Semitic<br />

xenophobia fostered by nativist organizations, the publication of<br />

the preliminary report of the Federal <strong>Immigration</strong> Commission at<br />

the end of 1910, <strong>and</strong> the increased unemployment <strong>and</strong> labor vio-<br />

lence that characterized the 1913-1915 economic recession.ls<br />

Quite naturally, organizations of "old" <strong>and</strong> "new" immigrants<br />

were the major force opposing immigration restriction. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Immigration</strong> Protective <strong>League</strong>, founded in 1898 by Americans of<br />

German <strong>and</strong> Irish descent <strong>and</strong> renamed the New Immigrants<br />

Protective <strong>League</strong> in 1906, led the campaign against restriction<br />

around the turn of the century. During the first decade of the twen-<br />

tieth century, however, the leadership of the movement against<br />

restriction gradually shifted to the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong> (NLIL) <strong>and</strong> the American Jewish Committee (AJC), both

Simon Wolf<br />

(183 6-1923)

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 207<br />

founded in 1906. <strong>The</strong> former, though organized by Jews, was a<br />

nonsectarian organization that included German, Irish, <strong>and</strong> Italian<br />

members as well as native-born Americans. <strong>The</strong> AJC was founded<br />

by German-Jewish leaders to defend the rights of Jews throughout<br />

the world. <strong>The</strong>se two organizations were behind the dem<strong>and</strong> that<br />

Congress establish an <strong>Immigration</strong> Commission to investigate all<br />

aspects of the immigration problem, a compromise proposal<br />

designed to counteract the growing pressure for a literacy test.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y led the campaign against restriction between 1906 <strong>and</strong> 1917,<br />

advocating continuation of the traditional American policy of free<br />

entry <strong>and</strong> refuting the ethnic-cultural <strong>and</strong> socioeconomic argu-<br />

ments invoked in favor of restriction. <strong>The</strong>y were opposed to any<br />

new immigration legislation, called for the fair administration of<br />

laws already on the books, <strong>and</strong> took a staunch st<strong>and</strong> in support of<br />

the right of asylum.'g<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> was formally organized<br />

in July 1906, following the successful mass meetings held in New<br />

York <strong>and</strong> Boston in June 1906 to protest the bill introduced by<br />

Senator Gardner of Massachusetts aimed at restricting immigra-<br />

tion.'"<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea of establishing the <strong>League</strong> originated in Alliance<br />

Israklite Universelle (AIU) circles in Boston <strong>and</strong> New York. <strong>The</strong><br />

AIU was a Jewish organization founded in France in 1860 by<br />

French-Jewish leaders in order to help Jews throughout the world,<br />

under the motto "All Jews are responsible for one another." <strong>The</strong><br />

purpose of the organization was "to secure for the Jews of the<br />

entire world civil <strong>and</strong> political rights." <strong>The</strong> AIU worked to achieve<br />

these objectives through political lobbying <strong>and</strong> a network of<br />

schools designed to help Jews assimilate into the mainstream of<br />

their country of residence. In 1901, Nissim Behar was sent to New<br />

York by AIU headquarters in Paris to establish a national branch in<br />

the United States." Soon after his arrival, Behar founded AIU local<br />

societies in New York <strong>and</strong> Boston, <strong>and</strong> established close contacts<br />

with Jewish leaders throughout the country through the<br />

Federation of Jewish Organizations of New York. On February 27,

208 Americnn Jezuislz Archives<br />

-.A-<br />

p"<br />

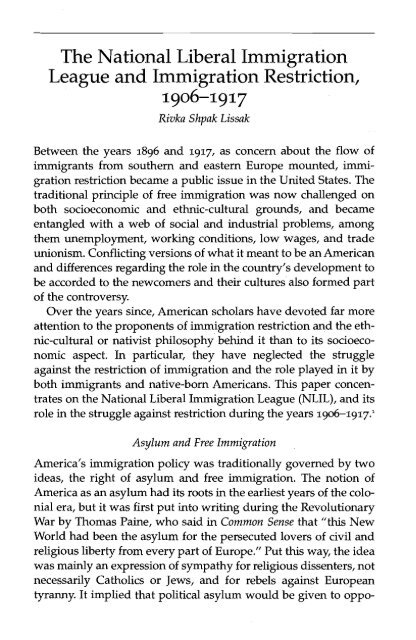

MONSTER MASS=MEETING<br />

TO PROTEST AGAINST<br />

W RESTRICTIONS OF IMMIGRATION<br />

dem<strong>and</strong>. of the rcstractto~urtr rn Cwgrtu for he hcdapmn of a Lteracy test. havrog lor<br />

the Ndw from thtn country .mually of thous<strong>and</strong>r of Hchrewr. Ilallans <strong>and</strong> the rcprualahvua<br />

d oth~ =hug oppartun~ty md frmlom undn our flag. have despt~c Ih slmpg &at moved<br />

bj lbcm throqh dr &<strong>and</strong> Honorable JAMES M CURLEY. .ad ahrr able <strong>and</strong> equally couragemr<br />

~ b d wen. c ~ qua brought the maner up for tmmedtate coruderahoo<br />

Up T h d y <strong>and</strong> Friday of ~hm week hcannw wdl h- held uodcr chc dmaon of<br />

Ca~aa JOHN L BURNETT. the arch eoemy d all f~rc~~ncrr to so codcaror lo m e<br />

&te mto law of thu hush .ad opprcwvc measure<br />

CONGRESSMAN CURLEY<br />

Wb a MW to mug a pmlat lo I d 1b.l tt. doa<br />

vS1 mmd m Ib h4I. of Cat- dl appear at 0Io<br />

MONSTFX PROTEST MEETING<br />

TO BB HECD AT<br />

cs&~(~<br />

TEMPLE<br />

Blue Hill <strong>and</strong> Lamnee Are+es<br />

on SUNDAY, DECEMBER 14, at 3.00 P. M.<br />

Wl All E@ALLV MOIISTER BATHERIN6 IN THE CRADLE OF UBERn<br />

FANEUIL HALL<br />

SUNDAY, DEC. 14, at 8.00 p. m.<br />

-<br />

HE HAS IWYITED &NO ACCEPTANCES VAVE 0EEH RECEIVED FROM<br />

JUDGE LEON SANDERS<br />

Dr HARRY LEVY of Commonwealth Temple<br />

MANUEL F W A R all of New York Dr RUBINOVITZ Morel<strong>and</strong> St Synagogue<br />

LOUIS LEVY, of Ph~ldelph~a<br />

Hm ANTONIO ZUCCA. of New York<br />

Rabb~ A COROVITZ, of Roxbury<br />

Rsbb~ P ISRAEL1,Adath Jnhurun Synagogue<br />

Hoa. JOHN J FRECHl of New York<br />

h. 9. J DRABINSKY of Brooklyn<br />

JACOB DE HAAS. Boaton Jcw~rh Advocate<br />

EZEKIEL LEAVI'IT. Ed~tor of &ston Votce<br />

Tk<br />

.mi 0th~. amd hu raemnd usurancafrom the foremot rsp-cn<br />

utl d .It .rca I. M~**achuactt., th.1 hey rill artend<br />

*- %Itm<br />

we owe ta lholc d our ract <strong>and</strong> Mod thc nM~ga~~on wr hold to ar ,\mencan crruc~<br />

davdrthe<br />

to ma=<br />

ol dl at thew meenng* hats have bern reserved lor ~hc I.&. <strong>and</strong> wt<br />

two gsrhcnnps ~h- most rrp.rrrn!allvr proar.l cwr recorded on lhr htvtonr d bton GTluru fa-.<br />

A poster announces the meeting of pro-immigrntion forces<br />

at Boston's Fanz~eil Hall<br />

-.-<br />

4

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 209<br />

1905 Philip Rubinstein, a Boston lawyer <strong>and</strong> secretary of the<br />

Boston AIU, suggested to Behar that he form "a federation of the<br />

different branches of the AIU in the various cities in this country,<br />

which federation would be in a better position to consider such<br />

large questions as anti-immigration laws <strong>and</strong> passport difficulty."<br />

<strong>The</strong> immigration committees of the Boston AIU <strong>and</strong> the Federation<br />

of Jewish Organizations of Massachusetts (FJOM) met on April 28,<br />

1906 to discuss the anti-immigration laws pending before<br />

Congress. This resulted in the drafting of a resolution against<br />

immigration restriction, a copy of which was sent to the congress-<br />

men <strong>and</strong> senators from Massachusetts in Washington. David A.<br />

Ellis, president of the Boston AIU <strong>and</strong> chairman of the immigra-<br />

tion committee of the FJOM, <strong>and</strong> its secretary, P. Rubenstein, urged<br />

Behar to suggest to all the other AIU societies in the country that<br />

they adopt similar resolutions <strong>and</strong> send copies <strong>and</strong> personal letters<br />

to members of Congress."<br />

<strong>The</strong> second activity against restriction sponsored by the AIU<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Federations of Jewish Organizations of New York <strong>and</strong><br />

Massachusetts was the organization of mass meetings in New York<br />

City <strong>and</strong> Boston, to which representatives of other nationalities<br />

were also invited. Thus, Italians participated in the Boston mass<br />

meeting held at Faneuil Hall on June 6, 1906, <strong>and</strong> Irish participat-<br />

ed in the New York mass meeting held at Cooper Union on June 4,<br />

1906. This pattern was repeated in other cities with large immi-<br />

grant populations. At the mass meetings resolutions were adopted<br />

against immigration restriction <strong>and</strong> delegations were appointed to<br />

present the resolutions to President Roosevelt, Speaker Cannon,<br />

<strong>and</strong> members of Congress.'3<br />

<strong>The</strong> success of these mass meetings in attracting the attention of<br />

public opinion in general, <strong>and</strong> of the President <strong>and</strong> Congress in<br />

particular, to the opposition to immigration restriction, persuaded<br />

Ellis <strong>and</strong> Behar of the need for a national nonsectarian organiza-<br />

tion to combat the organized efforts of the advocates of immigra-<br />

tion restriction. Behar had become convinced that his mission in<br />

America was not only to help Jewish immigrants from eastern<br />

Europe to adjust to their new country, but also to ensure that the<br />

flow of Jewish immigrants to America remained unchecked. He

210 American Jewish Archives<br />

believed that a non-Jewish organization devoted to keeping the<br />

doors of America open would better serve the needs <strong>and</strong> interests<br />

of Jewish immigrants. In short, the idea was to invite immigrant<br />

leaders, American-born businessmen, <strong>and</strong> other distinguished<br />

persons to join the <strong>League</strong>'s leadership in order to convince the<br />

American public that immigration was of economic benefit as well<br />

as a humanitarian issue, both in the spirit of American traditi0ns.q<br />

Behar convinced Edward Lauterbach, a well-known leader of<br />

the New York Jewish community <strong>and</strong> a famous lawyer involved in<br />

the public affairs of New York City, to use his close ties to non-<br />

Jewish leaders to help organize a nonsectarian national organiza-<br />

tion to combat restriction. Lauterbach, who was at that time also a<br />

member of the newly established AJC, accepted the challenge <strong>and</strong><br />

persuaded several organizations <strong>and</strong> individuals with a concern<br />

for immigration to join the initiative, forming the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong><br />

<strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong>. <strong>The</strong>se organizations participated in the first<br />

annual meeting of the <strong>League</strong>, held on March 10, 1908. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

included the New York branch of the Independent Order of B'nai<br />

B'rith, the Association for the Protection of Jewish Immigrants of<br />

Philadelphia, the Labor Information Office for Italians in New<br />

York, the German-American societies of New York, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Slavonic Immigrant Society.'5<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> was first mentioned in the Jewish press throughout<br />

the country in July-August 1906, following a letter signed by<br />

Edward Lauterbach, its first president, <strong>and</strong> addressed to the editors<br />

of the Jewish papers. <strong>The</strong> newspapers published the <strong>League</strong>'s<br />

prospectus, which informed readers that "the object of this non-sec-<br />

tarian <strong>League</strong> is to counteract the efforts of various organizations<br />

which have spread throughout the country, <strong>and</strong> which all have the<br />

same purposethe restriction if not the suppression of immigra-<br />

tion." Here the <strong>League</strong> articulated its aim as being "to preserve for<br />

our country the benefits of immigration while keeping out unde-<br />

sirable immigrants." <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> declared its commitment to the<br />

maintenance <strong>and</strong> enforcement of the existing laws "excluding crim-<br />

inals, paupers, persons having contagious diseases, <strong>and</strong> similar<br />

undesirable classes." Other than that, "there should be no further<br />

restriction of immigration." <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> also declared its commit-

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 211<br />

ment to the distribution <strong>and</strong> Americanization of immigrants as the<br />

solution to overcrowding <strong>and</strong> ethnic ~egregation.'~<br />

On March lo, 1908 the <strong>League</strong> held its first annual meeting, at<br />

which its constitution <strong>and</strong> by-laws were adopted. <strong>The</strong>se defined<br />

the purpose of its founders as: "uniting all American citizens who<br />

recognize the importance of immigration in the upbuilding of<br />

these United States in a combined effort to further the public inter-<br />

est through promoting the welfare of immigrants." <strong>The</strong> constitu-<br />

tion included five objectives aimed at achieving this purpose. First,<br />

"to effect the proper regulation of immigration <strong>and</strong> better distrib-<br />

ution of the immigrants." Second, "to diminish <strong>and</strong> prevent the<br />

overcrowding of immigrants in large cities, <strong>and</strong> especially at the<br />

ports of entry, by systematically aiding them to go to towns <strong>and</strong><br />

farming districts in different parts of the country where their ser-<br />

vices will be most available." Third, "to help immigrants to form<br />

in assigned localities such new settlements as will benefit both<br />

them <strong>and</strong> the community." Fourth, "to advocate the enactment of<br />

such legislation as will most effectually promote this direction of<br />

immigrants." Fifth, "to oppose any further increase of restrictions<br />

imposed by the present immigration laws, <strong>and</strong> all unjust <strong>and</strong> un-<br />

American methods of administrating these laws."'7<br />

<strong>The</strong> membership of the <strong>League</strong> consisted of both organizations<br />

<strong>and</strong> individuals, but only the organizational delegates-two for<br />

each member organization-had the right to vote at the <strong>League</strong>'s<br />

annual meetings. Its branches were entitled to one delegate for<br />

each fifty member^.'^<br />

<strong>The</strong> officers of the <strong>League</strong>, as stated in its constitution, were a<br />

president, five vice-presidents, a secretary, a treasurer, <strong>and</strong> a board<br />

of directors. <strong>The</strong> annual meeting of the <strong>League</strong> was set for "the<br />

month of May each year." <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> decided to form seven<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ing committees to help the officers <strong>and</strong> the board of directors<br />

to perform their duties. <strong>The</strong>se were: a general committee, an advi-<br />

sory committee, a membership committee, a committee on ways<br />

<strong>and</strong> means, an educational committee, a committee of observation,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a committee on public meetings.'g<br />

<strong>The</strong> annual meeting chose Edward Lauterbach as president, five<br />

vice-presidents, a secretary, <strong>and</strong> a treasurer. Nissim Behar was

212 American Jewish Archives<br />

nominated managing director of the <strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> occupied this<br />

post throughout the years of its existence. He was, in fact, its dri-<br />

ving force <strong>and</strong> moving spirit.3'<br />

<strong>The</strong> composition of the <strong>League</strong>'s general committee, as well as<br />

of its other committees, reflected its nonsectarian character in eth-<br />

nic, political, <strong>and</strong> occupational terms. <strong>The</strong> members included rep-<br />

resentatives of various ethnic <strong>and</strong> immigrant organizations,<br />

Democrats <strong>and</strong> Republicans, <strong>and</strong> persons from all walks of life:<br />

professors, clergymen, businessmen, <strong>and</strong> lawyers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Jews were represented by Simon Wolf, of the Independent<br />

Order of B'nai B'rith, president of the Union of American Hebrew<br />

Congregations, chairman of the Board of Delegates on Civil<br />

Rights, <strong>and</strong> a member of the <strong>National</strong> German American Alliance;<br />

Edward Lauterbach, president of the <strong>National</strong> Organization of<br />

Rumanian Jews in the United States, member of the board of direc-<br />

tors of the AIU <strong>and</strong> the advisory board of the Federation of Jewish<br />

Organizations of New York State, member of many other Jewish<br />

<strong>and</strong> non-Jewish welfare <strong>and</strong> educational associations, holder of<br />

leadership positions in the Republican Party of New York, a<br />

lawyer who had appeared "in some of the most noted legal con-<br />

tests," <strong>and</strong> a director of a large number of railroad <strong>and</strong> steamship<br />

companies; <strong>and</strong> Louis Edward Levy, a chemist, president of the<br />

Association for the Protection of Jewish Immigrants of Philadelphia,<br />

<strong>and</strong> later also of the Jewish Community (Kehilla) of Philadelphia.3'<br />

<strong>The</strong> Irish members included Michael J. Drummond, president of<br />

the Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick of New York, one of<br />

the major national Irish organizations, <strong>and</strong> a Commissioner of<br />

Charities of New York City; Thomas M. Mulry, a physician <strong>and</strong><br />

member of the board of managers of the Manhattan State Hospital,<br />

president of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, the largest Catholic<br />

welfare organization in the country, <strong>and</strong> vice-president of the<br />

Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick of New York; W. Bourke<br />

Cochran, former president of the <strong>Immigration</strong> Protective <strong>League</strong>, a<br />

prominent congressman, <strong>and</strong> one of the leaders of the Knights of<br />

Columbus, Free Irel<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the Ancient Order of the Hibernians;<br />

Charles J. Bonaparte, Attorney General of the United States <strong>and</strong><br />

leader of the Hibernian Society of Baltimore; <strong>and</strong> Michael F. Conry,

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 213<br />

representing the Irish Federation of New York.3'<br />

<strong>The</strong> Germans were represented by Dr. Gustav Scholer, a physician<br />

<strong>and</strong> member of the board of managers of the Manhattan State<br />

Hospital of New York, who represented the New York branch of<br />

the <strong>National</strong> German American Alliance (NGAA); Dr. C. J.<br />

Hexamer, president of the NGAA; Prof. Marion D. Learned of the<br />

Pennsylvania branch of the NGAA; Judge Herman C. Kudlich,<br />

vice-president of the New Immigrants Protective <strong>League</strong>; <strong>and</strong> John<br />

J. Hynes, president of the Catholic Mutual Benefit Association of<br />

Buffalo, New York, <strong>and</strong> vice-president of the American Federation<br />

of Catholic Societies.33<br />

<strong>The</strong> Italians included Antonio Stella, a consulting physician to<br />

the Manhattan State Hospital of New York, vice-president of both<br />

the Italian <strong>Immigration</strong> Society of New York <strong>and</strong> the Union <strong>League</strong><br />

of Italian-Americans; Antonio Zucca, the owner of a large import<br />

business, president of both the Italian American Democratic Union<br />

of Greater New York <strong>and</strong> the New York Italian Chamber of<br />

Commerce; <strong>and</strong> Benjamin F. Buck of the Italian American<br />

Agricultural Ass~ciation.~~<br />

<strong>The</strong> American Association of Foreign Language Newspapers<br />

(AAFLN), an organization representing the ethnic press throughout<br />

the country, was represented in the <strong>League</strong> by its president,<br />

Louis N. Hammerling, an immigrant from A~stria.~~ <strong>The</strong> business<br />

community was represented by noted businessmen <strong>and</strong> civicminded<br />

citizens, such as Andrew Carnegie of New York, a tycoon<br />

in the iron <strong>and</strong> steel industry; Frank S. Gannon <strong>and</strong> Grenville M.<br />

Dodge of the railroad business; <strong>and</strong> the bankers Robert Fulton<br />

Cutting <strong>and</strong> Cornelius N. Bliss. Cutting was also president of the<br />

New York Association for Improving Conditions of the Poor, <strong>and</strong><br />

a member of the national committee of the FIG. <strong>The</strong> business community<br />

of the southern states, which was interested in attracting<br />

immigrants to the South, was represented by Major Frank Y.<br />

Anderson, one of the leading citizens of Birmingham, Alabama,<br />

who was one of the vice-presidents of the <strong>League</strong>.36<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong>'s general committee also included persons of<br />

prominence in the academic world, such as Prof. Charles W. Eliot,<br />

president of Harvard University, <strong>and</strong> Woodrow Wilson, president

214 American Jewish Archives<br />

of Princeton University, <strong>and</strong> later governor of New Jersey <strong>and</strong><br />

President of the United States. Victor S. Clark, the <strong>League</strong>'s fifth<br />

vice-president, was an economist <strong>and</strong> investigator of labor condi-<br />

tions for the federal government <strong>and</strong> the author of many books on<br />

labor <strong>and</strong> economic problems. He <strong>and</strong> Isaac Hourwich, who was<br />

statistician at the federal Census Bureau <strong>and</strong> the author of<br />

<strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>and</strong> Labor, served as the <strong>League</strong>'s advisors.37<br />

<strong>The</strong> religious leadership of America was represented in the<br />

<strong>League</strong> by prominent ministers, such as Rev. Henry C. Potter, the<br />

Episcopalian bishop of New York; Rev. Charles H. Parkhurst, a<br />

Presbyterian minister <strong>and</strong> member of the national committee of<br />

the FRF; Rev. Percy Stinkney Grant, rector of the Church of the<br />

Ascension of New York <strong>and</strong> member of the national committee of<br />

the FRF; Rev. Thomas R. Slicer, a Methodist; <strong>and</strong> Rev. David James<br />

Burrell, author of many books on religion.?'<br />

<strong>The</strong> politicians represented on the <strong>League</strong>'s committees<br />

belonged to both the Republican <strong>and</strong> Democratic parties.<br />

Congressman Joseph G. Cannon, Speaker of the House of<br />

Representatives during the Roosevelt administration, was one of<br />

the first members of the <strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> served as its president for a<br />

short time during 1906 <strong>and</strong> from 1914 on. William S. Bennet,<br />

another Republican congressman, was on the <strong>League</strong>'s Advisory<br />

Committee <strong>and</strong> served as its vice-president from 1914. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong>'s general committee included two Democratic governors,<br />

William Sulzer of New York, a former congressman, <strong>and</strong> Judson<br />

Harmon of Ohio. It also included George Gordon Battle, a former<br />

associate district attorney of New York County, <strong>and</strong> General<br />

Benjamin F. Tracy, Secretary of the Navy, <strong>and</strong> later a judge of the<br />

New York Court of Appeals.39<br />

Of the seven st<strong>and</strong>ing committees appointed by the <strong>League</strong>, the<br />

only active ones were the advisory <strong>and</strong> education committees. It<br />

seems, however, that even these committees did not meet regular-<br />

ly, if at all, but the managing director conducted their business by<br />

regularly corresponding with members, keeping them informed<br />

<strong>and</strong> consulting them before making decisions, as the Behar-Eliot<br />

<strong>and</strong> Behar-Levy correspondence shows.<br />

Since the <strong>League</strong> did not have a permanent agent in

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 215<br />

Washington, it kept in close contact with several congressmen who<br />

acted as informal agents, thus keeping abreast of what was going<br />

on in the capital in regard to immigration restriction. Congressmen<br />

Bennet, who was a member of the <strong>Immigration</strong> Commission from<br />

1907 to 1910, reported on the Commission's work <strong>and</strong> also regu-<br />

larly reported on developments in the House of Representatives<br />

during his terms of office there in the years 1906-1911 <strong>and</strong><br />

1915-1917. Congressman James Curley of Massachusetts, served<br />

as the <strong>League</strong>'s unofficial agent between 1911 <strong>and</strong> 1914. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong> was also in contact with many senators <strong>and</strong> representa-<br />

tives who defended the cause of free immigration.@<br />

Although in terms of officials <strong>and</strong> committee members the<br />

<strong>League</strong> was nonpartisan <strong>and</strong> nonsectarian in nature, the organiza-<br />

tion was directed by its Jewish members. As we have seen, the<br />

main motivation behind the founding of the <strong>League</strong> was to secure<br />

an "open door" for Jews from eastern Europe. Taking into consid-<br />

eration the growing anti-Semitic feeling in the United States,<br />

resulting from the large influx of Jews fleeing from oppression,<br />

Jewish leaders were anxious to divert public attention from focus-<br />

ing only on Jewish immigration in order to prevent the identifica-<br />

tion of immigration as a "Jewish issue." Thus, the <strong>League</strong>'s policy<br />

was to conduct the campaign against restriction as an "American<br />

issue," emphasizing primarily the economic arguments against<br />

restriction, <strong>and</strong> relegating the humanitarian aspect of immigration<br />

to the background. In short, the <strong>League</strong> wished to prove its thesis<br />

that America needed the immigrant as much as the immigrant<br />

needed A~nerica.~'<br />

At the same time, the <strong>League</strong> wished to be recognized as an<br />

organization of "those without selfish interests at stake, those with<br />

altruistic motives." It presented itself to the American public as<br />

representing America's traditionally <strong>Liberal</strong> immigration policy<br />

combining the economic needs of the country with its humanitar-<br />

ian <strong>and</strong> democratic attitude toward immigrants. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong><br />

described its supporters as "those whose hearts have been touched<br />

by the appeal of their distressed brothers across the sea . . . those<br />

who want the immigrant for the good of this country with those<br />

who want him for their own good <strong>and</strong> those who want him for<br />

humanity's go0d."4~

216 American Jewish Archives<br />

<strong>League</strong> Activities<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> gave high priority to the<br />

publication <strong>and</strong> distribution of literature against immigration<br />

restriction. It published extracts from speeches by members of<br />

Congress against immigration laws, pamphlets containing the<br />

views of prominent persons against restriction, <strong>and</strong> anti-restriction<br />

pieces from the daily press. From time to time the <strong>League</strong> also pub-<br />

lished articles on economic <strong>and</strong> other issues connected with immi-<br />

gration. In their publications, statements, <strong>and</strong> addresses before dif-<br />

ferent organizations, <strong>League</strong> members analyzed the economic sit-<br />

uation in the United States <strong>and</strong> the role played by immigrant labor<br />

in the country's development <strong>and</strong> economic growth. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong><br />

argued that America still had millions of acres of unimproved<br />

l<strong>and</strong>, on the one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> a scarcity of labor in agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

industry, on the other.43<br />

Moreover, the <strong>League</strong> claimed that all the measures suggested<br />

for restricting immigration-the requirement that aliens possess a<br />

large sum of money; a high head tax; physical tests equivalent to<br />

those required for army recruits; a literacy test; a certificate of good<br />

moral character; <strong>and</strong> exclusion of aliens unable to pay for their<br />

transportation-were designed to stop immigration altogether, of<br />

both skilled <strong>and</strong> unskilled immigrants. Since, however, the litera-<br />

cy test seemed to have the greatest support in Congress, the<br />

<strong>League</strong> focused its efforts on this measure. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong>'s econom-<br />

ic experts offered data proving that a literacy test would deprive<br />

the country of its chief source of much-needed labor <strong>and</strong> result in<br />

a shortage of unskilled workers to the detriment of economic<br />

growth. It would "keep out of this country those you most need,<br />

able-bodied men who are anxious to plow <strong>and</strong> hoe, willing to use<br />

the pick <strong>and</strong> shovel, the very work which the native American has<br />

grown too prosperous or too ambitious to do."44<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> criticized the labor movement for its anti-immigrant<br />

policy, contending that "the objection to the immigrant is based on<br />

the false premise that the coming of the immigrant, by increasing<br />

the supply of labor, decreases the wages of labor." <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> pre-<br />

sented data proving that wages were going up despite increased

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 217<br />

immigration, that native-born American <strong>and</strong> "Old" immigrant<br />

workers from western <strong>and</strong> northern Europe were being "shoved<br />

upward," as the result of immigration, <strong>and</strong> that "without abun-<br />

dance of labor, enterprise <strong>and</strong> development are impossible." It<br />

claimed, therefore, that the problem was not restriction of immi-<br />

gration but the need to "look after the welfare of those who<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> pointed to the Contract Labor Law, introduced<br />

before Congress by labor unions, as "the greatest obstacle to get-<br />

ting the needed labor into this country." It therefore suggested<br />

amending Section 4 of this law to read as follows: "That it shall be<br />

a misdemeanor for any person, company or corporation, in any<br />

manner whatsoever, to prepay the transportation or in any way to<br />

assist or encourage the importation or immigration of any contract<br />

laborer or laborers into the United States, unless a copy of the con-<br />

tract between the employer <strong>and</strong> such laborer or laborers, in the<br />

language of the said laborers, is given them <strong>and</strong> duplicates filed<br />

with the Commissioner of <strong>Immigration</strong> or his representative at the<br />

port of entry; provided that said contract is not, in the judgement<br />

of the Commissioner or his representative, at a rate of wages lower<br />

than the current wages in the section to which the laborer is des-<br />

tk1ed."4~<br />

<strong>The</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> that contract labor enter the country only on con-<br />

dition that the rate of wages was not lower than the st<strong>and</strong>ard in the<br />

United States was designed to answer organized labor's argument<br />

regarding the competition posed by cheap foreign workers. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>League</strong>'s leaders believed that the amended law would secure bet-<br />

ter, not cheaper workers, <strong>and</strong> that when there was no dem<strong>and</strong> for<br />

them they would simply go back home.47<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> considered the creation of a mass movement against<br />

immigration restriction to be crucial to its success in combating the<br />

organizations active in the campaign for restriction, especially the<br />

AFL. <strong>The</strong> immigrant community of America was the natural target<br />

of the <strong>League</strong>'s efforts to organize such a mass movement.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first object of the <strong>League</strong>'s campaign was, as a matter of<br />

course, the Jewish community. It sought to organize branches in<br />

Jewish centers throughout the country, using the Jewish press <strong>and</strong>

218 American Jewish Archives<br />

the <strong>League</strong>'s own agents to spread the news of the founding of the<br />

organization <strong>and</strong> explain its aims <strong>and</strong> tactics. As a newcomer<br />

unacquainted with the American way of doing things, Behar<br />

enlisted the help of Louis E. Levy of Philadelphia as his adviser,<br />

using his services to make personal contact with immigrant lead-<br />

ers <strong>and</strong> businessmen <strong>and</strong> to draft circulars <strong>and</strong> appeals.4'<br />

In 1906-1907, the <strong>League</strong> formulated the pattern of its activities<br />

in the Jewish community. <strong>The</strong>se models were later applied to the<br />

immigrant community at large, <strong>and</strong> were followed until 1915. <strong>The</strong><br />

Jewish papers received "Appeals to the Jewish Press," "Letters to<br />

the Editors," <strong>and</strong> circulars from the <strong>League</strong>'s president <strong>and</strong> man-<br />

aging director in which they explained their aims, advising Jewish<br />

readers to urge their local organizations to rally mass meetings<br />

against restriction <strong>and</strong> invite all immigrant groups to participate,<br />

adopt resolutions against restriction, send letters to senators <strong>and</strong><br />

congressmen, <strong>and</strong> nominate delegates to go to Washington to<br />

protest before the President <strong>and</strong> the Speaker of the House of<br />

Representatives against pending laws to restrict immigration.<br />

Individuals were urged to support the cause by sending letters <strong>and</strong><br />

petitions to their congressional representatives. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> print-<br />

ed in the Jewish press the form to be used in preparing petitions.<br />

Jewish organizations were urged to initiate campaigns on the city<br />

<strong>and</strong> state level to generate public opinion against restriction, <strong>and</strong><br />

to call upon mayors, councilmen, <strong>and</strong> state legislators to endorse<br />

the policy of an "open door." In December 1906 the <strong>League</strong> issued<br />

"An Appeal to American Citizens" against further restrictions,<br />

signed by mayors, clergymen, immigrant leaders, <strong>and</strong> Jane<br />

Addams, a prominent <strong>Liberal</strong> Progressive <strong>and</strong> a friend of lab0r.~9<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> planned to form its branches within the nationwide<br />

network of existing Jewish organizations, later inviting organiza-<br />

tions of other nationalities to join, thus establishing its nonsectari-<br />

an character. <strong>The</strong> AIU societies of New York <strong>and</strong> Boston were the<br />

first to become branches of the NLIL. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> sent agents to<br />

centers of Jewish population, such as Boston (Louis Gordon),<br />

Philadelphia (M. S. Margolis <strong>and</strong> later B. A. Sekely), Pittsburgh,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Galveston. <strong>The</strong>se were Yiddish-speaking agents recommend-<br />

ed by Levy, who made "strenuous efforts to reach every Jewish

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 219<br />

organization <strong>and</strong> have them learn what is meant by the two pend-<br />

ing [immigration] bills." Levy <strong>and</strong> Behar planned the "formation<br />

of a local Jewish Federation <strong>and</strong> branch of the <strong>League</strong>" in<br />

Philadelphia <strong>and</strong> Pittsburgh. Behar wrote in March 1907 to Dr. M.<br />

Spitz, editor of the Jezuish Voice of St. Louis, as well as to other edi-<br />

tors, asking that they "send him names for whom we could apply<br />

to help in the formation of the branch."<br />

In September 1907, Behar was informed by the <strong>League</strong>'s agent<br />

in Galveston that a branch was about to be organized by a Mr.<br />

Cohen, with the aim of including "Jews, Protestants <strong>and</strong> non-reli-<br />

gious sects." Lauterbach also wrote to Jewish leaders throughout<br />

the country suggesting the organization of other branches. In<br />

December 1906, he was informed by E. M. Baker, secretary of the<br />

Clevel<strong>and</strong> Federation of Jewish Charities, that he planned "to call<br />

together in a conference representative citizens of the various<br />

denominations <strong>and</strong> nationalities <strong>and</strong> with them organize a <strong>Liberal</strong><br />

<strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong>." In January 1907, the Jewish organizations of<br />

Worcester, Massachusetts, established the Worcester branch of the<br />

<strong>League</strong> together with immigrant organizations representing all the<br />

other nationalities in town. Gradually, branches were formed in<br />

Philadelphia, San Francisco, <strong>and</strong> other immigrant centers. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were meant to be self-supporting <strong>and</strong> autonomous, maintaining<br />

contact with <strong>League</strong> headquarters in New York for their instruc-<br />

tion~.~~<br />

<strong>The</strong> Jewish press cooperated willingly with the <strong>League</strong>. Jacob de<br />

Haas, editor of the Boston Advocate <strong>and</strong> one of the leaders of the<br />

Jewish community of Boston, committed his newspaper, as did<br />

other editors, to "making an effort weekly to interest the people to<br />

become more conversant with what is at present going on about<br />

them," asking all his readers "to take immediate action in this mat-<br />

ter by writing to their congressman <strong>and</strong> asking him to spare no<br />

efforts to prevent the [immigration] bills from becoming law.<br />

WRITE TODAY FOR TOMORROW MAY BE TOO LATE." <strong>The</strong> edi-<br />

tors published the <strong>League</strong>'s letters, circulars, <strong>and</strong> other literature,<br />

urged the Jews to organize branches, <strong>and</strong> recommended that their<br />

readers contribute money to meet the <strong>League</strong>'s expense^.^'<br />

<strong>The</strong> Germans were the second group approached by the <strong>League</strong>.

220 American Jewish Archives<br />

Lauterbach took advantage of his connections with German leaders<br />

in New York City, <strong>and</strong> in 1908 the first German branch of the <strong>League</strong><br />

was formed there. Gustav Scholer represented the branch on the<br />

<strong>League</strong>'s general committee. Gradually, branches were established<br />

in other centers of German population. <strong>The</strong>se were actually branch-<br />

es of the <strong>National</strong> German American Alliance (NGAA), the national<br />

organization of German societies in the United States. Cooperation<br />

between the NGAA <strong>and</strong> the NLIL was made possible by the rela-<br />

tionship between Levy of Philadelphia <strong>and</strong> J. Hexamer, president of<br />

the NGAA, <strong>and</strong> was very fitful. <strong>The</strong> NGAA declared at its annu-<br />

al convention, held in October 1907, that "It opposes any <strong>and</strong> every<br />

restriction of immigration of healthy persons from Europe, exclusive<br />

of convicted criminals <strong>and</strong> anarchists."<br />

During the years 1907-1915, NGAA <strong>and</strong> its branches through-<br />

out the country held protest meeting against immigration restric-<br />

tion, sent petitions to the President, the Speaker, <strong>and</strong> local con-<br />

gressmen <strong>and</strong> senators, <strong>and</strong> participated in hearings before con-<br />

gressional committees <strong>and</strong> presidential hearings on immigration.<br />

<strong>The</strong> St. Louis branch was one of the most active. Missouri, an area<br />

that was one of the largest centers of German population, wanted<br />

immigrants to settle <strong>and</strong> develop the state, <strong>and</strong> the Missouri<br />

<strong>Immigration</strong> Society associated itself with the <strong>League</strong> for this pur-<br />

pose. Thus, the congressmen <strong>and</strong> senators from Missouri,<br />

Representative Richard Bartholdt, one of the leaders of the NGAA,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Senators William J. Stone <strong>and</strong> James A. Reed, cooperated with<br />

the <strong>League</strong>, <strong>and</strong> were at times instrumental in resisting restriction<br />

bills. Through the NGAA, the <strong>League</strong> received contributions from<br />

German-American agents of German steamship companies, such<br />

as the Hamburg-American Line, as well as from other German-<br />

American businessmen. <strong>The</strong>se corporations had an interest in the<br />

continuation of unchecked immigration from Europe, but being<br />

immigrants or sons of immigrants themselves, they were, at the<br />

same time, motivated by a sense of solidarity with the plight of<br />

immigrants in general. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> also formed close relations<br />

with the leaders of the New Immigrants Protective <strong>League</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

one of its vice-presidents, Judge Herman C. Kudich, was a mem-<br />

ber of the NLIL's general committee.5'

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 221<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> also became closely connected with New York<br />

City's Irish <strong>and</strong> Italian leaders, as revealed by the names of its<br />

committee members. Compared to the Jews <strong>and</strong> the Germans,<br />

however, the Irish were much less active in organizing a central-<br />

ized effort against restriction through their national organizations.<br />

Neither were the Italians very effective on the national level.<br />

Nevertheless, New York's Italian societies <strong>and</strong> the Italo-American<br />

Alliance of the United States sent petitions <strong>and</strong> delegates to the<br />

President <strong>and</strong> Congress <strong>and</strong> participated in hearings before con-<br />

gressional committees <strong>and</strong> in presidential hearings on immigra-<br />

tion under the <strong>League</strong>'s auspices.53<br />

In 1910, the <strong>League</strong> enlisted the support <strong>and</strong> cooperation of the<br />

American Association of Foreign Language Newspapers<br />

(AAFLN), established in 1908, with its president, Louis N.<br />

Hammerling, joining the <strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> becoming a member of the<br />

advisory committee <strong>and</strong> later of the general committee. As the<br />

major channel of information <strong>and</strong> interpretation of American life<br />

for immigrants, the foreign-language newspapers were of utmost<br />

importance in spreading word of the <strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> its aims, <strong>and</strong> in<br />

recruiting immigrant organizations of all nationalities for the cam-<br />

paign against restriction. <strong>The</strong> American Leader, the organ of the<br />

AAFLN, became an aggressive advocate of an "open door" policy,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Association sent petitions <strong>and</strong> letters to the President <strong>and</strong><br />

the Speaker <strong>and</strong> participated in hearings before congressional<br />

committees <strong>and</strong> presidential hearings on immigrati~n.~~<br />

Due to its cooperation with the AAFLN headquarters in New<br />

York, the <strong>League</strong> was able to establish direct communication with<br />

editors of the non-Jewish foreign press, who were in most cases<br />

also leaders of their immigrant communities. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> prepared<br />

appeals <strong>and</strong> other literature in foreign languages to be printed in<br />

the foreign press <strong>and</strong> distributed by foreign-language-speaking<br />

agents among their countrymen. Levy was instrumental in enlist-<br />

ing the services of these agents.<br />

<strong>The</strong> editors were thus instrumental in creating awareness<br />

among the foreign population of the issue of immigration restric-<br />

tion <strong>and</strong> in mobilizing its participation in mass meetings. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

also helped in uniting immigrant organizations in every immi-

222 American Jewish Archives<br />

grant center for concerted action against immigration restriction.<br />

Such cooperation between editors <strong>and</strong> the <strong>League</strong> is revealed in<br />

the correspondence between Behar <strong>and</strong> Giovanni M. Di Silvestro,<br />

editor of La Voce del Popolo of Philadelphia <strong>and</strong> one of the leaders<br />

of the Order of Sons of Italy on the adoption of resolutions in favor<br />

of the <strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> its liberal immigration policy at the Italian<br />

Convention of 1911, <strong>and</strong> with James V. Donnaruma, editor of the<br />

Gazzetta del Massachusetts, who received a letter of thanks from<br />

Behar on January 14, 1913, for his cooperation "in behalf of our<br />

cause," with the expressed hope that he would "continue it <strong>and</strong><br />

have petitions circulated amongst, <strong>and</strong> signed by the largest pos-<br />

sible numbers of citizens of all races <strong>and</strong> origins." From time to<br />

time the <strong>League</strong> also held meetings with editors of the foreign-lan-<br />

guage newspapers in immigrant centers, as part of its efforts to<br />

mobilize immigrants of all nationalities, along with their leaders.<br />

Such meetings were held in March 10, 1908 in Philadelphia,<br />

attended by representatives of immigrant organizations, <strong>and</strong> in<br />

Chicago in November 1913.55<br />

In short, the <strong>League</strong> was successful in mobilizing the immigrant<br />

population, especially Jews, Germans, <strong>and</strong> Italians, for the cam-<br />

paign against restriction. Under its auspices, immigrant organiza-<br />

tions created local branches in centers of immigrant population.<br />

Thus the <strong>League</strong>'s structure gradually emerged. It was neither a<br />

centralized organization exercising control over its branches or<br />

affiliated organizations, nor a democratic association of affiliated<br />

societies. Rather it was a loose framework of independent organi-<br />

zations united upon short notice from the headquarters in New<br />

York for the purpose of ad-hoc cooperation on the city level.<br />

Contact between the <strong>League</strong>'s headquarters <strong>and</strong> its so-called<br />

branches was maintained through regular correspondence<br />

between Behar or his secretaries <strong>and</strong> the presidents of the affiliat-<br />

ed organizations or the branches. In this manner, the <strong>League</strong> kept<br />

its members informed as to what was going on in Washington <strong>and</strong><br />

sent them its instructions.<br />

Campaign Against the <strong>Immigration</strong> Bill<br />

Between 1906 <strong>and</strong> 1915, the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong>

<strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong> 223<br />

initiated three nationwide waves of protest, from April 1906 to<br />

February 1907, January 1911 to February 1913, <strong>and</strong> April 1913 to<br />

February 19x5. <strong>The</strong> pattern of the <strong>League</strong>'s protest movement was<br />

formulated during the first wave of 1906-1907, <strong>and</strong> improved dur-<br />

ing the second campaign, when it reached the peak of its success.<br />

Nevertheless, after 1912 the <strong>League</strong> was confronted with a serious<br />

crisis related to its policies as well as financial difficulties <strong>and</strong> the<br />

bankruptcy of its president's business, which greatly reduced its<br />

effectiveness. While in 1913-1914 the protest movement was spon-<br />

sored simultaneously by both the <strong>League</strong> <strong>and</strong> the AJC, by the<br />

1914-1915 campaign the <strong>League</strong>'s role was greatly reduced. From<br />

then on, although it continued to exist, its role was insignificant.<br />

<strong>The</strong> purpose of the first wave of protest movements was to<br />

defeat the 1906 immigration bill, which included, among other<br />

restrictive provisions, a literacy test. <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>ed that a<br />

federal commission be established to investigate all aspects of the<br />

immigration problem. "Our motto is," Behar wrote Levy, to "side<br />

track the bill, <strong>and</strong> postpone all action till the investigation com-<br />

mission has reported, at any rate till the next season." <strong>The</strong> <strong>League</strong><br />

planned to use the period of the investigation to influence public<br />

opinion <strong>and</strong> establish a consensus against re~triction.5~<br />

As already stated, the 1906-1907 protest movement began with<br />

mass meetings in Boston <strong>and</strong> New York in June 1906, <strong>and</strong> was<br />

taken up in other cities. <strong>The</strong> speakers at these meetings were rep-<br />

resentatives of immigrant organizations, politicians of both par-<br />

ties, religious leaders, <strong>and</strong> occasionally businessmen, <strong>Liberal</strong><br />

Progressives, <strong>and</strong> leaders of immigrant trade unions. <strong>The</strong> meetings<br />

typically adopted resolutions against restriction, designated dele-<br />

gations to go to Washington to protest before Congress <strong>and</strong> the<br />

President, <strong>and</strong> called the members of the organizations represent-<br />

ed to send petitions to their c~ngressmen.~~<br />

<strong>The</strong> 1906-1907 campaign against immigration restriction was<br />

fruitful from the <strong>League</strong>'s point of view, since it achieved its major<br />

objective. In February 1907 Congress formed an <strong>Immigration</strong><br />

Commission to investigate all aspects of the immigration problem,<br />

postponing consideration of the Literacy test for the time being. In<br />

a letter to the <strong>League</strong> sent on February 19, 1907, Congressman

224 American Jewish Archives<br />

Bennet congratulated the <strong>League</strong> for its role in defeating some of<br />

the restrictions included in the 1906 immigration bill, <strong>and</strong> urged its<br />

leaders to continue the campaign against restriction. "I cannot<br />

speak too highly of the work of your <strong>League</strong> during this Congress,<br />

without which it is quite certain there would have been an educa-<br />

tional test on the Statute books to-day, thus excluding yearly about<br />

200,000 deserving immigrant~."5~<br />

<strong>The</strong> Jewish press <strong>and</strong> Jewish<br />

leaders shared this view. Isidor Phillips, a Jewish leader from<br />

Boston, wrote Behar on March 29, 1907: "I have great pleasure in<br />

commending the work <strong>and</strong> progress achieved by the <strong>National</strong><br />

<strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong> <strong>League</strong>, in which you are such an ardent<br />

worker, <strong>and</strong> its success thus far, on behalf of free immigration."59<br />

In December 1910, the <strong>Immigration</strong> Commission published its<br />

preliminary report. <strong>The</strong> evidence upon which the Commission had<br />

based its conclusions <strong>and</strong> the recommendations contained in it<br />

were not included in the report. <strong>The</strong> Commission's thesis was that<br />

immigration restriction was an economic necessity required to<br />

protect the welfare of the American working class, <strong>and</strong> recom-<br />