V12 #1 November 1990 - Archives - The Evergreen State College

V12 #1 November 1990 - Archives - The Evergreen State College

V12 #1 November 1990 - Archives - The Evergreen State College

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

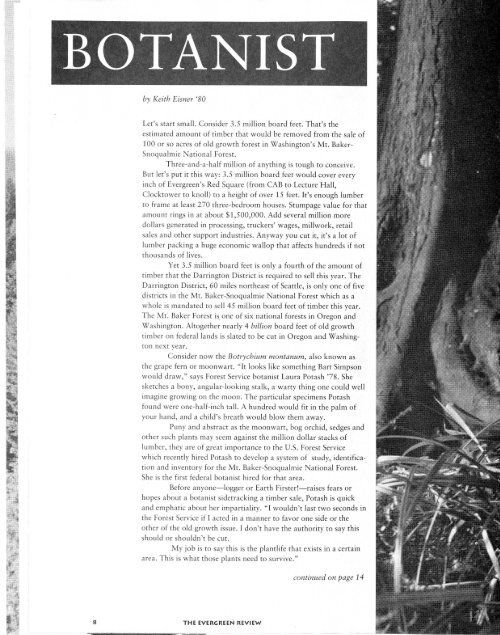

BOTANIST<br />

continued from page 8<br />

Although it is within the<br />

realm of possibility that a<br />

timber sale could be delayed or<br />

cancelled because of a plant,<br />

Potash hastens to point out<br />

that most forestry issues are<br />

not black-and-white, cut-ordon't-cut<br />

situations.<br />

"Say we find moonwarts,"<br />

she says, "or any other<br />

sensitive or endangered species<br />

on a proposed timber site. It's<br />

not a matter of 'Well there's a<br />

moonwart, so no sale.' <strong>The</strong><br />

first thing we do is determine<br />

the requirements for the<br />

species, then write about<br />

impacts: how changes in the<br />

soil, hydrology and light<br />

conditions will affect the plant.<br />

"<strong>The</strong>n we try to work<br />

with timber crews, engineers<br />

and other people in the Forest<br />

Service. For example, perhaps<br />

the road crew could change the<br />

spacing between culverts to<br />

lessen changes in the hydrology,<br />

or maybe the species can<br />

withstand flooding if a certain<br />

amount of the canopy is left<br />

intact or maybe..."<br />

Two million acres is another<br />

tough concept to grasp. Think<br />

of it this way: imagine covering<br />

the <strong>Evergreen</strong> campus on foot,<br />

from soccer fields to Organic<br />

Farm, from bus loop to<br />

Geoduck Beach, not missing a<br />

square foot. Now imagine<br />

2,000 <strong>Evergreen</strong>s, laid out<br />

together with no easy trails,<br />

mown lawns or predominantly<br />

gentle terrain. Imagine miles of<br />

devil's club, wetlands, tall<br />

timber, rivers, boulders,<br />

wilderness and clear cut.<br />

Those 2 million acres are<br />

Potash's venue, a roughly 30mile-wide<br />

corridor of forest in<br />

central Washington, extending<br />

from the Mt. Rainier area to<br />

the Canadian border. Of<br />

course, no human or conceiva-<br />

bly workable group of humans<br />

could cover that area in depth<br />

in a lifetime. What it will take<br />

to produce a reasonable profile<br />

of plantlife in the forest is<br />

nothing less than first-rate<br />

thinking, planning and<br />

teamwork.<br />

And there's the rub.<br />

Nothing manmade is as<br />

complex and mystifying as the<br />

biodiversity of an old growth<br />

forest. But the machinery of<br />

bureacracy conies close.<br />

Forestry issues involve huge,<br />

interlocking, interrelated<br />

government entities: Congress,<br />

the USD A, the Forest Service,<br />

Fish and Wildlife, Department<br />

of Natural Resources and state<br />

safety inspectors just to name a<br />

few. Bear in mind that each<br />

agency consists of hundreds of<br />

people in sub-agencies often on<br />

the ready to fight for turf,<br />

authority and jurisdiction.<br />

Throw in lawyers, media, and<br />

advocacy groups from timber<br />

and environmental camps and<br />

you have a minefield of<br />

personal and political crosspurposes.<br />

Daunting?<br />

"This is the job," says<br />

Potash, "that I've always<br />

wanted." Her enthusiasm for<br />

the task is genuine and<br />

infectious. At her desk and in<br />

the woods itself, she emanates<br />

a zest for discovery and making<br />

things work.<br />

Her desk in Seattle is a<br />

testament to the double life of<br />

field botanist and administrator:<br />

word processing manual;<br />

phone and rolodex; a thick-asa-Bible<br />

volume entitled Final<br />

Environmental Impact<br />

<strong>State</strong>ment; a plastic-coated field<br />

guide to flora of the Pacific<br />

Northwest; a memo typed<br />

military-style (ALL CAPS) from<br />

a forest ranger; an organization<br />

chart; a metric ruler; two sizes<br />

of tweezers; a magnifying glass,<br />

and two ziplock plastic bags<br />

containing green and swampylooking<br />

plants.<br />

14 THE EVERGREEN REVIEW<br />

"Those are sedges," she<br />

says, "It's odd to sit here at a<br />

desk, under florescent lights<br />

and examine plants. It's a lot<br />

harder identifying things in the<br />

field. You can't pick the<br />

sensitive or endangered plants.<br />

Usually I'm squatting down in<br />

the rain, crawling under devil's<br />

club to look at them."<br />

<strong>The</strong> phone rings and she<br />

engages in a lively conversation<br />

about swamp gentians. "It's a<br />

sexy project," she says, "People<br />

love bogs. I'd like to do it<br />

myself."<br />

She's talking with a Forest<br />

Service employee responsible<br />

for the rare plants program at<br />

the North Bend station. He and<br />

Potash are discussing the pros<br />

and cons of recruiting members<br />

of private conservation groups<br />

to volunteer for the enormous<br />

task of plant study in the<br />

national forests.<br />

"On the other hand," she<br />

says, "you don't want to take a<br />

lot of people out there. It's a<br />

delicate situation, socially and<br />

ecologically."<br />

After the call Potash<br />

explains it's a new ballgame<br />

with plants in the Forest<br />

Service. Some districts are very<br />

interested, others don't have<br />

the time, and some just don't<br />

want to be bothered. Creating<br />

a network of people who care<br />

about rare plants and have the<br />

expertise to identify them is<br />

one of Potash's top priorities.<br />

"Hopefully we'll train timber<br />

cruisers and other Forest<br />

Service people to be on the<br />

lookout for rare species."<br />

<strong>The</strong> image is captivating:<br />

everyone from engineers and<br />

surveyors to roadbuilders and<br />

loggers paying as much<br />

attention to what's on the<br />

ground as to the 400-year-old<br />

giants towering over them.<br />

Potash's first fieldwork<br />

took place over 14 years ago as<br />

an <strong>Evergreen</strong> student when she<br />

studied at the Malheur Bird<br />

Observatory in Oregon and<br />

observed elephant seals at the<br />

Point Reyes Observatory in<br />

California. Last year she<br />

earned a masters degree in<br />

ecosystems analysis from the<br />

University of Washington,<br />

writing her thesis on "Sprouting<br />

of Red Heather in Response<br />

to Fire."<br />

I wondered why someone<br />

so active would chose to<br />

specialize in botany rather than<br />

wildlife. One of the reasons is<br />

simple. <strong>The</strong> reality of wildlife<br />

research means hours of sitting<br />

motionless in observation<br />

blinds. She also loves the<br />

intellectual challenge of keying<br />

a plant: "You become aware of<br />

the evolutionary relationships<br />

between organisms."<br />

Three days after visiting her<br />

office, I accompany Potash to a<br />

stand of old growth timber, the<br />

Darrington sale referred to<br />

earlier in this story. We are<br />

members of a party of 15<br />

who'll review the proposed<br />

timber site. <strong>The</strong>re's a silviculturist,<br />

an Audubon Society<br />

member, a member of the<br />

Nature Conservancy, a wildlife<br />

biologist, fisheries biologist, an<br />

hydrologist, a timber management<br />

officer, foresters and the<br />

district ranger. <strong>The</strong>re's also a<br />

representative for the Tulalip<br />

tribe whose interest is the<br />

shrinking area of natural forest<br />

suitable for ceremonial<br />

purposes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hike is a traveling<br />

seminar. <strong>The</strong> group strings out<br />

into little ad hoc discussion<br />

groups of twos and threes, with<br />

topics ranging from the<br />

abstraction of policies,<br />

agencies, theories and politics<br />

to the here-and-now of this<br />

Douglas Fir, this Western<br />

Hemlock. Every now and then<br />

with no formal notice or<br />

apparent organization, the<br />

entire group gathers to discuss<br />

the implications of the sale. We<br />

stand quiet for awhile, blinking<br />

at the trees above us until<br />

someone starts to speak.<br />

I Most of the talk is over my<br />

head: windthrow, blowdown,<br />

corridors, sunscald, storage,<br />

recharge, canopy intersection,<br />

fragmentation, overstory,<br />

understory, exploding growth,<br />

edge. I am reminded of the<br />

saying that Eskimos have over<br />

100 words for ice and snow.<br />

Likewise, those of us on the<br />

periphery of forests think<br />

generally in two words, "big"<br />

and "trees," while people like<br />

Potash and her co-workers<br />

have developed a whole lexicon<br />

to deal with the complexity of<br />

forest life.<br />

One phrase that continually<br />

surfaces is "New Perspectives."<br />

It's the new thinking<br />

that recognizes a forest as a<br />

complex, biological community<br />

rather than just a woodlot.<br />

Recognizing the biodiversity of<br />

a forest is one thing. Removing<br />

400-year-old, twenty-ton trees<br />

and recreating that diversity of<br />

life is something else again.<br />

It's all new territory. What<br />

trees and how many do we<br />

leave standing? Should we cut<br />

lots of little sections or several<br />

huge stands? What actually<br />

lives here now? What'll happen<br />

in 80, 100, 300 years? Will we<br />

have recreated a forest or a<br />

treelot? No one knows for<br />

sure. It's like giving a pocket<br />

watch to a five-year old and<br />

asking her to take it apart and<br />

put it together again.<br />

But there's hope in<br />

knowledge. A year ago there<br />

was no botanist for this forest.<br />

Now she's up ahead with a 10pound<br />

field guide tucked into<br />

the back pouch of her rain<br />

parka. It's also safe to say that<br />

a few years ago there probably<br />

wouldn't have been an<br />

hydrologist, a biologist, an<br />

environmentalist, a journalist<br />

or a tribal representative<br />

present on this survey.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re's hope, too, in<br />

communication. A fair amount<br />

of networking takes place on<br />

the hike: Potash and the<br />

hydrologist discuss what<br />

constitutes wetlands; the<br />

wildlife specialist discusses<br />

shade and seedling growth with<br />

the silviculturist; a timber<br />

cruiser and an environmentalist<br />

discuss the effects of blowdown<br />

on the edge of the proposed<br />

cut. Every exchange of<br />

knowledge and resources<br />

contributes a tiny piece to the<br />

puzzle of a forest.<br />

Later, I ask Potash about her<br />

piece of the puzzle. We're<br />

driving back to Seattle and I<br />

drop my Greener Environmentalist<br />

Chic and play the devil's<br />

advocate: "Okay, really, Laura,<br />

job responsibilities and correct<br />

politics aside, why all this fuss<br />

about moonwarts and other<br />

weeds?"<br />

Her response is calm but<br />

impassioned: "We don't know<br />

the long-term effects of our<br />

actions. It's presumptuous to<br />

assume we do. Take the fungus<br />

they've discovered on the roots<br />

of trees. <strong>The</strong>y've found out that<br />

that fungus helps trees grow.<br />

"Who knows? Maybe the<br />

moonwart could be a cure for<br />

AIDS or cancer. Not protecting<br />

it would be like burning the<br />

pages of a book before you've<br />

read it."<br />

She pauses as we enter the<br />

city. "Even if moonwarts are of<br />

absolutely no use to humans,<br />

we don't have the right to<br />

destroy any species or to allow<br />

them to be destroyed."<br />

In these hard times, it<br />

takes more than compassion to<br />

do the right thing for our<br />

forests. It takes knowledge<br />

about all life-great and<br />

microscopic. What Potash and<br />

her co-workers are giving us is<br />

as precious as water.<br />

ACTIVIST<br />

continued from page 11<br />

Olympic Peninsula from the<br />

bottom of the pile and starts<br />

flipping through orange and<br />

green overlays. Numbered tags<br />

scattered across the map<br />

indicate the known locations of<br />

spotted owls. <strong>The</strong> wealth of<br />

biological data contained in<br />

these maps is impressive.<br />

While working on a World<br />

Wildlife Fund project in the<br />

Amazon rain forest, Steel<br />

became acquainted with the<br />

concept of island biogeography:<br />

the study of changes in<br />

animal and plant populations<br />

that occur when large tracts of<br />

habitat are broken into isolated<br />

patches by natural or human<br />

activity. This is essentially what<br />

is happening in the Northwest<br />

and is at the core of the fight<br />

over how much old growth<br />

forest needs to be preserved.<br />

"Before the days of the<br />

spotted owl, conservation was<br />

a recreational issue. <strong>The</strong> 'Name<br />

it and Save it' philosophy<br />

guided legislation," he explains,<br />

referring to the point of<br />

view that it was easier to get<br />

Congress to save pretty places<br />

than to preserve animal<br />

habitat. "<strong>The</strong> ancient forests<br />

used to be thought of as<br />

biological deserts," he says,<br />

pointing out the dwindling<br />

islands of green on the map<br />

overlay. "As we learned more<br />

about their diversity of life it<br />

became evident that we needed<br />

to shift from thinking about<br />

landscapes to thinking about<br />

whole ecosystems. At last we're<br />

recognizing the importance of<br />

forests as biological areas."<br />

After jobs with the Forest<br />

Service and the Washington<br />

<strong>State</strong> Department of Wildlife,<br />

<strong>The</strong> Audubon Society put Steel<br />

to work organizing the map<br />

library. It didn't take them long<br />

to recognize his skill for<br />

organizing people. "I was in<br />

the right place at the right<br />

time," he says. He believes the<br />

Audubon Society was one of<br />

the first national organizations<br />

to shift its emphasis to "deep<br />

ecology." This required a reevaluation<br />

of what was<br />

politically possible for the<br />

FALL <strong>1990</strong><br />

movement. It meant education<br />

and involving a much larger<br />

part of the population.<br />

Steel sees Washington<br />

state as particularly fertile<br />

ground for political action.<br />

"This is the best lab in the<br />

country right now to see if<br />

people can live in a healthy<br />

environment. We still have a<br />

few areas that are virtually the<br />

same as they were before the<br />

arrival of white men. At the<br />

same time we have a public<br />

that's concerned about<br />

environmental issues. <strong>The</strong><br />

combination of both factors is<br />

something unique in the<br />

U.S. I believe that if we can't<br />

practice wise forestry in the<br />

Pacific Northwest, we can't do<br />

it anywhere."<br />

<strong>The</strong> term "grass roots"<br />

keeps coming up when you<br />

talk to Argon Steel. For him,<br />

environmentalism is a populist<br />

movement. He sees danger in<br />

the tendency to focus on<br />

lobbying in Washington D.C.<br />

at the expense of working in<br />

the community. "<strong>The</strong> next big<br />

issue for environmental groups<br />

is how to integrate youth and<br />

minorities into the movement,"<br />

he said. "I'm hoping<br />

this campaign will recognize<br />

that minorities have their own<br />

agendas, and the environmental<br />

movement has room<br />

for those agendas. I'd like to<br />

look beyond saving your local<br />

marsh and look at the larger<br />

issues that surround people."<br />

For Steel these larger<br />

issues are economic. "In the<br />

near future we are going to see<br />

more confrontations between<br />

economic interests and<br />

endangered species." He<br />

doesn't believe it's going to be<br />

possible to legislate environmentalism<br />

without making<br />

fundamental changes. "I'm a<br />

little more radical than some<br />

of my fellow environmentalists,"<br />

he admits with a vaguely<br />

dangerous smile.<br />

"Let me tell you what my<br />

priorities are. My first<br />

allegiance is to the environment.<br />

My second is to the<br />

continued on next page<br />

15