The Spot Prawn Fishery The Spot Prawn Fishery - Basel Action ...

The Spot Prawn Fishery The Spot Prawn Fishery - Basel Action ...

The Spot Prawn Fishery The Spot Prawn Fishery - Basel Action ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

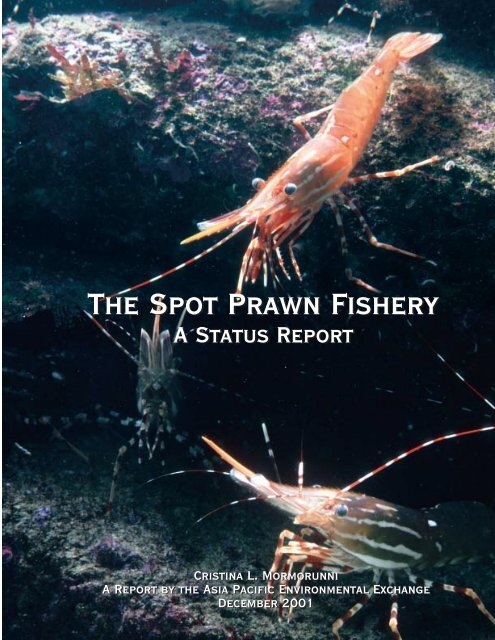

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

A Status Report<br />

Cristina L. Mormorunni<br />

A Report by the Asia Pacific Environmental Exchange<br />

December 2001

THE SPOT PRAWN FISHERY<br />

A STATUS REPORT<br />

Cristina L. Mormorunni<br />

A Project of the Asia Pacific Environmental Exchange<br />

December 2001

THE SPOT PRAWN FISHERY:<br />

A STATUS REPORT<br />

A PROJECT OF<br />

APEX is devoted to promoting Ecosystem Health and Ecological Economics in natural resource management<br />

and preventing the globalization of the toxic crisis. We focus our work in the Cascadia region of North<br />

America and the Asia-Pacific.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

<strong>The</strong> David and Lucille Packard Foundation<br />

1305 4th Avenue, Suite 606 • Seattle, WA 98101<br />

Tel.: 206.652.5555 • Fax: 206.652.5750<br />

Email: apex@seanet.com • www.a-p-e-x.org<br />

Editing: Isabel de la Torre and Richard Lehnert<br />

Cover Design and Printing: Jan Pomeroy and Paper Tiger<br />

Cover Photo: Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation – Kathleen Olson<br />

Report Photos: Nick Lowry, K.M. Kattilakoski<br />

Graphics: ADFG, CDFG, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, WDFW<br />

APEX would also like to thank the many individuals who generously assisted with this report<br />

by providing information, expertise, and comments.<br />

Printed on 100% recycled, chlorine-free paper.

CONTENTS<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................i<br />

PREFACE ...................................................................................................................i<br />

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................1<br />

ECOLOGY OF THE SPOT PRAWN .............................................................................2<br />

Life History and Geographic Range ............................................2<br />

Predator-Prey Relationships.......................................................5<br />

Factors Affecting <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Success.........................................6<br />

AN OVERVIEW OF SPOT PRAWN MANAGEMENT ..................................................6<br />

ALASKA SPOT PRAWN FISHERY .............................................................................6<br />

Biological Status of <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>s ................................................6<br />

History of the <strong>Fishery</strong> ................................................................7<br />

Nature of the <strong>Fishery</strong> Today .......................................................9<br />

Landings, Landed Values, and Markets........................................11<br />

Existing Management and Regulatory Systems...........................12<br />

Management Issues and Concerns.............................................14<br />

BRITISH COLUMBIA SPOT PRAWN FISHERY ..........................................................14<br />

Biological Status of <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>s ................................................14<br />

History of the <strong>Fishery</strong> ................................................................15<br />

Nature of the <strong>Fishery</strong> Today .......................................................16<br />

Landings, Landed Values, and Markets........................................19<br />

Existing Management and Regulatory Systems...........................19<br />

Management Issues and Concerns.............................................21<br />

WASHINGTON SPOT PRAWN FISHERY ...................................................................24<br />

Biological Status of <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>s ................................................24<br />

History of the <strong>Fishery</strong> ................................................................26<br />

Nature of the <strong>Fishery</strong> Today .......................................................30<br />

Landings, Landed Values, and Markets........................................32

Existing Management and Regulatory Systems...........................32<br />

Management Issues and Concerns.............................................35<br />

OREGON SPOT PRAWN FISHERY ...........................................................................35<br />

Biological Status of <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>s.................................................35<br />

History of the <strong>Fishery</strong> ................................................................36<br />

Nature of the <strong>Fishery</strong> Today .......................................................36<br />

Existing Management and Regulatory Systems...........................36<br />

Management Issues and Concerns.............................................37<br />

CALIFORNIA SPOT PRAWN FISHERY ......................................................................38<br />

Biological Status of <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>s.................................................38<br />

History of the <strong>Fishery</strong> ................................................................38<br />

Nature of the <strong>Fishery</strong> Today .......................................................39<br />

Landings, Landed Values, and Markets........................................41<br />

Existing Management and Regulatory Systems...........................42<br />

Management Issues and Concerns.............................................42<br />

RECOMMENDATIONS ..............................................................................................45<br />

Approach of the Recommendations ...........................................45<br />

Ecological Sustainability and Scale of the <strong>Fishery</strong>.........................45<br />

Fair Distribution—Democracy in Regulation and<br />

Management ............................................................................52<br />

Economic Efficiency ..................................................................55<br />

WHERE TO FROM HERE ...........................................................................................56<br />

REFERENCES.............................................................................................................57<br />

CONTACTS AND INTERVIEWEES .............................................................................61

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

This report could not have happened without<br />

the vision and support of Dave Batker and APEX.<br />

I want to thank him for possessing the intellect,<br />

perseverance, and drive needed to ensure a quality<br />

product, one that will significantly contribute to<br />

the management of spot prawns and fisheries in<br />

general.<br />

I also want to express my appreciation and gratitude<br />

to the many individuals and organizations<br />

that contributed their knowledge, expertise, and<br />

experience to this report. It is a much stronger<br />

document for your efforts. I especially appreciate<br />

the time that many of you took to review, and<br />

review, and review the document so that it was as<br />

accurate, tight, and information-rich as it possibly<br />

could be. Your fingerprints—or, should I say, keystrokes—are<br />

all over this document, and you<br />

share equally in its eventual success.<br />

Thanks to the Lucille and David Packard Foundation<br />

for seeing the importance of this project and<br />

for supporting APEX. Will Novy Hildesley, Associate<br />

Program Officer at <strong>The</strong> Packard Foundation,<br />

must be thanked for offering enthusiasm, encouragement,<br />

and support that went well beyond the<br />

call of duty.<br />

Finally, to the spot prawn, for without you, none<br />

of this would have happened.<br />

PREFACE<br />

What is the Asia Pacific<br />

Environmental Exchange?<br />

<strong>The</strong> Asia Pacific Environmental Exchange (APEX)<br />

was founded in 1997 in order to develop new,<br />

innovative, and collaborative strategies that would<br />

lead to the creation of sustainable environmental<br />

policies and natural resource management systems.<br />

APEX’s guiding mission is to apply the theory and<br />

1 <strong>The</strong> field of Ecological Economics “is not a single new paradigm based<br />

in shared assumptions and theory” (Costanza et al. 1997, p. 50). Ecological<br />

Economics is deliberately transdisciplinary or pluralistic and works<br />

from the initial premise that the “earth has a limited capacity for sustainably<br />

supporting people and their artifacts determined by combinations<br />

of resource limits and ecological thresholds” (Costanza et al. 1997,<br />

p. 75). Human economic systems are seen as a subset of, and entirely<br />

dependent on, natural ecosystems.“Ecological economists are rethinking<br />

both ecology and economics to better understand the nature of<br />

biodiversity, and arguing from biological theory how natural and social<br />

systems have co-evolved together such that neither can be understood<br />

apart from the other” (Costanza et al. 1997, p. 50). Elements of<br />

both ecology and economics, and the links that exist between them,<br />

such as resource economics and environmental impact assessment, are<br />

principles of Ecological Economics 1 and Ecosystem<br />

Health 2 , two current academic fields, to international,<br />

national, and regional environmental<br />

policy (see “Ecological Economics and Ecosystem<br />

Health” boxes in the “Recommendations” section<br />

for an expanded description of these academic<br />

fields). APEX campaigns on the vital issue areas<br />

of toxics, trade, forests, and marine ecosystems<br />

in order to concretize these theories and demonstrate<br />

that economic health and environmental<br />

sustainability can be mutually reinforcing. <strong>The</strong><br />

organization is also focused on preventing the<br />

globalization of obsolete environmental and<br />

economic policies by such international forums<br />

as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World<br />

Bank, and the Asian Development Bank (ADB).<br />

APEX’s Marine Program—<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Project<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Project is the platform upon<br />

which APEX intends to build its Marine Programs.<br />

This project will allow APEX to apply its vision,<br />

academic base, and cooperative campaign strategies<br />

to the marine environment, establishing a<br />

unique niche in the marine conservation community.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Project’s multiple and far-reaching benefits<br />

will extend to the marine environment and to<br />

fishing communities, and will influence existing<br />

systems of fisheries management.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cutting-edge disciplines of Ecological Economics<br />

and Ecosystem Health will be used to shift<br />

the spot prawn fishery toward long-term ecological,<br />

economic, and sociocultural sustainability.<br />

This is critical; although there are myriad international<br />

and national laws and management systems<br />

established to protect our oceans, fishery collapse<br />

and habitat destruction continue. New and innovative<br />

approaches are vital.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Project has the potential to protect<br />

more than just spot prawns. Its goals and<br />

strategies are aimed at providing a concrete vision<br />

relied upon in assessing and directing development projects and<br />

resource management.<br />

2 <strong>The</strong> academic discipline of Ecosystem Health believes that the health<br />

of an ecosystem is determined by four major characteristics: sustainability,<br />

activity, organization, and resilience. “An ecological system is<br />

healthy and free from ‘distress syndrome’ (irreversible process of system<br />

breakdown leading to collapse) if it is stable and sustainable—that<br />

is, if it is active and maintains its organization and autonomy over time<br />

and is resilient to stress” (Costanza et al. 1992, p. 9). According to the<br />

practitioners of Ecosystem Health, this definition can and should be<br />

applied to all complex systems, and takes into account the fact that<br />

ecosystems will grow and evolve in response to both the natural and<br />

cultural environments within which they are rooted.<br />

i

ii<br />

for marine sustainability and fisheries conservation<br />

that is influential and meaningful for managers,<br />

fishers, and the general public. <strong>The</strong> public<br />

and political momentum created will have the<br />

capacity to reform fisheries management and the<br />

management of shrimp fisheries (both wild and<br />

cultured) in the United States and abroad.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Status Report—What is it?<br />

What is it not?<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report (Status<br />

Report) is the result of a first-ever review of the<br />

fishery. <strong>The</strong> impetus for the Report was APEX’s<br />

view that until a foundational understanding of<br />

the fishery was obtained, assessing the fishery’s<br />

sustainability or the measures needed to shift the<br />

fishery toward sustainability could not accurately<br />

be determined.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Status Report will serve as the <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong><br />

Project’s foundational document and the source<br />

of the Project’s goals, strategies, and recommendations<br />

for spot prawn management. <strong>The</strong> Status<br />

Report is not an exhaustive treatise on spot prawns<br />

and their management. Rather, it offers a horizontal<br />

slice of the greater spot prawn picture. Future<br />

investigations will be vertical slices that arise naturally<br />

as the work progresses and the Project develops.<br />

Every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of<br />

the data and that all sources of information were<br />

tapped. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that the<br />

Status Report contains errors. It is likely that facts<br />

have been omitted; that the players and the playing<br />

field have changed; that dates and information<br />

are out of date before the report is even published.<br />

For these reasons, the Status Report makes no pretense<br />

of being the definitive document on spot<br />

prawns and their management. This is a starting<br />

point—an attempt to sketch the state of knowledge<br />

and the parameters of the debate so that all<br />

interested parties have a common starting point<br />

for discussion, agreement, and dissent. <strong>The</strong> Status<br />

Report is a living document that will be revised<br />

and reworked as the need presents itself and the<br />

information becomes available.<br />

Research and Report Methodology<br />

<strong>The</strong> principal research and writing of this report<br />

took place between February and September of<br />

2001. Sources of information include the peerreviewed<br />

literature, unpublished papers, government<br />

documents, and numerous interviews via<br />

e-mail, telephone, and in person. All efforts were<br />

made to locate and use the best and most recent<br />

data. Where available, we included data from the<br />

2000–01 fishing season, with the bulk of numbers<br />

coming from the 1999–00 season. All sources are<br />

listed at the end of the document and inserted in<br />

the text where it was determined to be particularly<br />

important to cite the reference or resource.<br />

I take personal responsibility for all factual errors<br />

in this report. It should be noted that major contributors,<br />

particularly at the State and Provincial<br />

level, reviewed the document for errors and omissions.<br />

In almost all cases, the document reflects<br />

the suggested changes.<br />

Report Outline<br />

<strong>The</strong> Status Report begins with a general discussion<br />

of the biology and ecology of spot prawns.<br />

This is followed by: an analysis of the fishery’s<br />

management systems, region by region (Alaska,<br />

British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and<br />

California); the biological status of spot prawns;<br />

the history of the fishery; the nature of the fishery<br />

today; landings, landed values, and markets; and<br />

existing management and regulatory systems.<br />

Future management issues and concerns are<br />

detailed for each region.<br />

<strong>The</strong> information in the Report was obtained<br />

through standard research methods or provided by<br />

interviewees and contacts. I took great measures<br />

to prevent APEX’s opinions or recommendations<br />

from creeping into the analysis and discussion. By<br />

contrast, the “Recommendations” and “Where To<br />

from Here?” sections of the Report are the opinions<br />

of APEX, grounded in our investigation and<br />

examination of the fishery, discussions with a wide<br />

range of experts, and our own expertise and experience<br />

in the management of marine ecosystems.

INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn fishery spans diverse habitats<br />

and ecosystems. <strong>The</strong> scientific, management,<br />

and cultural systems that have evolved with it are<br />

equally diverse. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status<br />

Report seeks to accurately reflect the ecology and<br />

management of this complex fishery. This information<br />

allows identification of aspects of the<br />

fishery that uphold the precautionary principles<br />

of Ecosystem Health and Ecological Economics,<br />

aspects that undermine these tenets and warn<br />

of unsustainability, and aspects that require<br />

further investigation.<br />

Why the <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>?<br />

Pressure on marine ecosystems grows each year<br />

as seafood becomes a greater part of the American<br />

diet. Although there is increasing awareness<br />

of the various threats that undermine the viability<br />

of marine ecosystems, existing laws and regulations<br />

have largely failed to secure sustainable fisheries<br />

or to protect the intimate connection between<br />

the economy and the ecosystem evident in marinedependent<br />

communities. <strong>The</strong> record of fisheries<br />

management in the 20th century is dismal.<br />

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture<br />

Organization (FAO), 11 of the world’s 15<br />

most important fishing areas and 60% of commercially<br />

significant fish species are in decline (FAO<br />

1997, McGinn, A.P. 1998). According to an FAO<br />

press release, 25% of the world’s marine fishery<br />

stocks, including many individual species of fish,<br />

are being overfished (Associated Press 2001).<br />

Recently, the United States Department of<br />

Commerce reported that the number of US fish<br />

species in jeopardy continues to rise, and reached<br />

a record 107 species in 2000 (Marine Fish Conservation<br />

Network 2001). Commemorating the United<br />

Nations’ Year of the Ocean (1998), more than 1,600<br />

marine scientists, oceanographers, and fishery<br />

biologists from around the world issued a joint<br />

statement, entitled “Troubled Waters,” alerting<br />

the international community to the global marine<br />

crisis and the forces driving it. <strong>The</strong>se included<br />

pollution, habitat degradation, and wasteful and<br />

destructive fishing practices (MCBI 1998).<br />

<strong>The</strong> problems facing the oceans are clear. As fishery<br />

after fishery collapses, it is imperative that we<br />

ask “Why?” and “What could have been done differently?”<br />

Marine sustainability requires true<br />

understanding of the factors that lead to the<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

destruction of marine species, and the ecosystems,<br />

economies, and cultures dependent<br />

on them. It requires evolution of existing management<br />

philosophies and paradigms. A broad knowledge<br />

of marine systems and a vision for sustainability<br />

are therefore at the crux of protecting our<br />

natural systems. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status<br />

Report seeks to assemble this type of information<br />

for one marine species before it is too late.<br />

Shrimp Fisheries in Context<br />

Shrimp—harvested in the wild or produced via aquaculture—are<br />

generally characterized as among<br />

the most unsustainable of all global fisheries.<br />

Destructive fishing methods, vast quantities of<br />

bycatch, loss of mangroves, and coastal pollution<br />

are only a few of the serious environmental and<br />

social problems that have been associated with<br />

the wild harvest and aquaculture of shrimp. Yet<br />

shrimp is also one of the fastest-growing and most<br />

lucrative global and domestic seafood markets.<br />

Shrimp are one of the most valuable seafood<br />

products imported into the United States. In 2000,<br />

US shrimp imports were valued at US $3.8 billion.<br />

In 2001, imports are expected to reach 775–785<br />

million pounds—a value of between US $3.5 and<br />

$3.8 billion (Department of Agriculture 2001).<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Marine Fisheries Service reports<br />

that nearly one billion pounds of shrimp were<br />

consumed in the US in 1998, and that consumption<br />

levels continue to rise (National Marine<br />

Fisheries Service 1999a).<br />

Unfortunately, the vast majority of shrimp consumers<br />

do not know that the unsustainable production<br />

and harvest of shrimp is devastating<br />

ecosystems and local communities. Moreover,<br />

they have no way of identifying or ordering sustainably<br />

produced shrimp in a restaurant or<br />

supermarket. <strong>The</strong>re is a critical need to establish<br />

an ecologically certified, sustainable shrimp fishery<br />

that can be used to educate consumers, shift<br />

seafood demand to more ecologically sound<br />

products, and dramatically reduce demand<br />

for unsustainably produced seafood.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn fishery on the West Coast of<br />

North America, extending from Alaska to<br />

California, has great potential to be an exception<br />

to the ecological and social destruction that typifies<br />

many shrimp fisheries. This potential is a<br />

function of several factors:<br />

•the ecological sensitivity of spot prawns and<br />

1

2<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

their critical habitat has been recognized and<br />

reflected in most of the fishery’s management<br />

•the fishery is primarily a community-based fishery,<br />

with a great deal of fisher involvement in<br />

management<br />

•the high-value and expanding markets for spot<br />

prawn product lead to a greater “value” placed<br />

on the conservation and sustainability of the<br />

species<br />

•managers commonly recognize that constant<br />

refinement and improvement of the management<br />

system is a prerequisite for long-term<br />

sustainability<br />

APEX’s initial research indicates that the spot<br />

prawn fishery has the potential to:<br />

•be the first shrimp fishery managed according<br />

to the precautionary principles of Ecosystem<br />

Health and Ecological Economics<br />

•be the first shrimp fishery market-certified for<br />

its sustainability.<br />

•provide an example of a fishing technology that<br />

minimizes habitat destruction, reduces bycatch,<br />

and provides a high-quality, high-value product<br />

•play an important role in informing consumers<br />

about the true environmental and social costs<br />

of shrimp fisheries, thereby leading to a reduction<br />

in consumption of unsustainable seafood<br />

•serve as an example of sustainable fisheries<br />

management nationally and internationally<br />

An Overview of Project<br />

Goals and Strategies<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Project strategy focuses on influencing<br />

existing management systems, educating<br />

consumers and the public, and creating discerning<br />

markets for sustainable seafood. <strong>The</strong> Project seeks<br />

to create a new language of fisheries management<br />

—one that encompasses the principles of precautionary<br />

management, Ecological Economics, Ecosystem<br />

Health, proper temporal and geographic<br />

scale, just distribution, and transparent, democratic<br />

decision-making. Specifically, the principles of<br />

Ecological Economics and Ecosystem Health will<br />

be used to define marine sustainability and move<br />

the spot prawn fishery toward this standard.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Project aims to advance a sustainable and<br />

certifiable fishery from San Diego, California to<br />

Dutch Harbor, Alaska. A tangible vision for evolving<br />

existing systems of fisheries management will<br />

be provided. We also expect the spot prawn fishery<br />

to become a sustainable model for other fisheries<br />

in the US and for shrimp fisheries worldwide.<br />

ECOLOGY OF THE SPOT PRAWN<br />

Life History and Geographic Range<br />

Pandalus platyceros is in the Crustacean Decapod<br />

Family Pandalidae and is commonly known as the<br />

spot prawn or spot shrimp. This Family contains<br />

medium to large shrimp that inhabit continental<br />

shelves and slopes worldwide. At least 18 species<br />

in two genera have been recognized, a portion of<br />

which support commercial fisheries (California<br />

Department of Fish & Game 1995).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong><br />

Photo Courtesy K.M. Kattilakoski, Fisheries and Oceans Canada<br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn is the largest of the pandalid<br />

shrimp, with a carapace length—measured from<br />

the posterior eye orbit to the posterior mid-dorsal<br />

margin of the carapace—of 61.1 millimeters (2.4<br />

in.) (Butler 1980). <strong>Spot</strong> prawns are characterized by<br />

stout bodies that are light brown to orange in color<br />

and have white-paired spots behind the head and<br />

in front of the tail. <strong>The</strong> adult carapace is often distinguished<br />

by white stripes that run from the anterior<br />

to posterior (top to bottom) of the animal.<br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn’s geographic range extends from<br />

Southern California to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands,<br />

around to the Sea of Japan and the Korea Strait<br />

(Watson 1994). Anecdotal evidence suggests<br />

that the spot prawn’s range may in fact extend<br />

into Mexico, where a small fishery (±3 vessels)<br />

is reported to exist off the coast of Baja California<br />

(Nick Lowry, University of Washington School of<br />

Fisheries. Pers. comm., May 2001). None of the<br />

literature reviewed mentioned the possibility of<br />

the spot prawn’s range extending beyond the California<br />

border. <strong>The</strong> Status Report does not attempt<br />

to substantiate or disprove these observations,<br />

although this may be an important issue for<br />

scientists and managers to consider.

<strong>Spot</strong> prawns typically inhabit rocky or hard bottoms,<br />

including reefs, coral or glass-sponge beds,<br />

and the edges of marine canyons. In part, species<br />

abundance is determined by the natural productivity<br />

levels characteristic of an area. Distribution<br />

is a function of the temperature and salinity of<br />

the water, and the animal’s developmental stage.<br />

Immature shrimp are able to tolerate greater ranges<br />

in both these factors and are found in shallower<br />

depths than adults. Common depth ranges extend<br />

from the intertidal to 487 meters (1,607 feet). <strong>Spot</strong><br />

prawns are typically found at depth’s of between<br />

198 and 234 meters (653–772 feet).<br />

Research carried out by Schlining (1999) investigates<br />

spot prawn habitat and distribution. Detailed<br />

examination of video transects in, close<br />

to, and outside an ecological reserve in the<br />

Monterey Bay area revealed that spot prawns<br />

are not simply distributed in the most commonly<br />

available habitat type. Although the nature or pattern<br />

of selection is unclear, active habitat selection<br />

seemed to be taking place. Habitat types associated<br />

with spot prawns varied by depth. <strong>Spot</strong> prawns<br />

were more commonly associated with complex<br />

habitats of mixed sediment and smaller rock types<br />

such as gravel and cobble. <strong>The</strong> animals were also<br />

associated with large aggregations of drift algae,<br />

where this existed.<br />

Distribution appeared to be very patchy. A finding<br />

that Schlining (1999) correlates with local trap fishers’<br />

reports suggests that spot prawns may be vulnerable<br />

to local overfishing and serial depletion<br />

(Orensanz 1998). <strong>The</strong> factors determining the size<br />

and location of patches are unclear, but are probably<br />

influenced by spot prawn habitat selection and<br />

larval transport (Lowry, University of Washington<br />

School of Fisheries. Pers. comm., May 2001).<br />

Juvenile spot prawns concentrate in shallow<br />

inshore areas (

4<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

spawning characteristically occurs earlier. Each<br />

animal spawns once as a male and once or more<br />

as a female. Spawning takes place at depths of<br />

151–212 meters (500–700 feet). Female fecundity<br />

(number of eggs) is a function of the animal’s size<br />

and ranges from 1,400 to 5,000 eggs for the first<br />

spawning, approximately 1,000 for the second<br />

spawning.<br />

Females carry the eggs under their tails on appen-<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Life History<br />

dages called swimmerets or pleopods. Fertilized<br />

and developing eggs are carried for four or five<br />

months, until they hatch, usually over a 10-day<br />

period. Upon hatching, the larvae enter a pelagic<br />

life stage in the water column. Larvae can remain<br />

free-swimming for up to three months, their<br />

movements potentially influenced by tides and<br />

currents (Boutillier and Bond 1999a). It is important<br />

to note that estimates of the larval stage vary<br />

considerably with geographic region.<br />

Diagram Courtesy Jim Boutillier,<br />

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Once the larvae begin to settle out, they migrate<br />

to inshore habitats suitable for growth and maturation,<br />

where they are believed to enter a relatively<br />

sedentary stage. While adult prawns have been<br />

known to move up and down in the water column<br />

in a diel (24-hour) migration pattern, it is not<br />

known if extended lateral migrations to adjoining<br />

coastal areas occur. Unpublished tagging studies<br />

carried out by J.A. Boutillier of Fisheries and<br />

Oceans Canada suggest that mature animals<br />

Egg-Bearing Female<br />

Photo Courtesy K.M. Kattilakoski, Fisheries and Oceans Canada<br />

“remained within one mile or two of their<br />

release location over a period of several months”<br />

(Boutillier and Bond 1999a).<br />

Other indicators, such as parasite loads and<br />

growth rates, vary considerably between prawn<br />

stocks separated by even tens of kilometers. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

support the view that, once the animals settle, little<br />

movement occurs (Bower and Boutillier 1990,<br />

Bower et al. 1996). Log books and catch samples<br />

suggest that a single year-class could settle in a<br />

particular area, live out its life cycle, and leave the<br />

area “virtually barren” when the year class dies off<br />

(Boutillier and Bond 1999a). If this is in fact the<br />

case, it is likely that there are hundreds of independent,<br />

localized adult stocks throughout the<br />

spot prawn’s geographic range.<br />

However, “the concept of meta-populations 3<br />

(mixed common populations) that share larvae<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

may well apply to prawns because of their lengthy<br />

pelagic larval stage” (Boutillier and Bond 1999a).<br />

Studies looking at smooth pink shrimp off the west<br />

coast of Vancouver Island have shown sequential<br />

recruitment among the population. This supports<br />

the concept of metapopulation trends in the region.<br />

Catch sampling data have illustrated good recruitment<br />

of a single spot prawn year-class over a fairly<br />

large area (Boutillier unpublished data, cited in<br />

Boutillier and Bond 1999a). It will be challenging<br />

to understand these processes and the factors<br />

and relationships affecting them.<br />

<strong>The</strong> abundance of egg-bearing females, the timing<br />

and length of spawning, the rates of development<br />

and growth, and larval production and survival<br />

are all influenced and controlled by water temperatures.<br />

In any given year, larval survival is affected<br />

by climatic conditions; for example, prevailing ocean<br />

currents. <strong>The</strong>se can contain larvae in certain areas<br />

and possibly expose them to differing concentrations<br />

of planktonic foods, thus affecting growth<br />

rates in early life stages. In addition, the amount<br />

of quality habitat available to settling juveniles is<br />

likely to play a significant role in overall survival<br />

and population abundance (David Love, ADFG.<br />

Pers. comm., February 2001).<br />

Predator-Prey Relationships<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> prawns are opportunistic foragers that typically<br />

feed on other shrimp, plankton, small mollusks,<br />

worms, sponges, and dead animal material. Adults<br />

are believed to be benthic (bottom) feeders that forage<br />

mostly at night. <strong>Spot</strong> prawns in turn are prey for<br />

other pelagic and demersal marine predators.<br />

As has been reported in other parts of the world<br />

for Pandalus borealis eous, or the pink shrimp,<br />

predators can play an important role in determining<br />

the reproductive success and recruitment of<br />

spot prawns to the fishery. To date, such studies<br />

have not been conducted in the spot prawn’s geographic<br />

range. Mortality due to predation is likely<br />

to be quite high during the larval and juvenile<br />

stages, but is significantly reduced once the animals<br />

settle out of the water column (Fisheries and<br />

Oceans 2000a). In benthic habitats, spot prawns<br />

__________________________________________________________<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> term metapopulation was first defined by Levins (1969) as “a<br />

population of populations” that occupies a certain percentage of the<br />

suitable habitat available (Vandermeer and Carvajal 2001). Levins<br />

(1969) theorized that increases in local extinction rates or reductions in<br />

colonization rates threaten the long-term viability of a given metapopulation.<br />

Numerous studies have provided support for these ideas, illustrating<br />

that local extinction rates increase with a decrease in the size of<br />

habitat patches, and colonization rates decrease as distances between<br />

habitat patches increase (Vandermeer and Carvajal 2001).<br />

5

6<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

are prey for bottom-dwelling fish and octopus.<br />

Mid-water fish species such as salmon are not<br />

known to prey on spot prawns.<br />

<strong>The</strong> abundance of predator species may have an<br />

effect on the abundance of spot prawns and other<br />

shrimp species. A study in the Barents Sea demonstrated<br />

a significant negative correlation between<br />

the abundances of cod and northern pink shrimp<br />

(Berenboim et al. 1996). Several other studies provide<br />

evidence that where fishing pressure has<br />

reduced predator populations, prey populations<br />

have increased (Witman and Sebens 1992; Aronson<br />

1989). Conversely, it is possible that the<br />

removal of shrimp by a commercial fishery plays<br />

a role in reducing the population of predator<br />

species (Fisheries and Oceans 2000b).<br />

Factors Affecting <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Success<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> prawn reproductive and recruitment success<br />

is dependent on and likely to be affected by a broad<br />

range of environmental variables, ecological factors,<br />

and changes in ambient conditions. It is important<br />

to consider environmental parameters in the development<br />

of management systems. <strong>The</strong> following elements<br />

are likely to affect the “success” of spot prawn<br />

reproduction and recruitment (ADFG 1985):<br />

•variation in preferred water temperatures, pH<br />

levels, dissolved oxygen concentrations, and/or<br />

the general chemical composition of the water<br />

•modification of critical benthic habitat<br />

•alterations of intertidal areas<br />

•increases of suspended organic or mineral<br />

material<br />

•reduced food supply<br />

•reduced protective cover; e.g., seaweed beds<br />

•obstruction of migratory pathways<br />

•level of harvest<br />

AN OVERVIEW OF<br />

SPOT PRAWN MANAGEMENT<br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn fishery spans an enormous and<br />

diverse stretch of ecosystems and management<br />

jurisdictions. While there are inherent similarities<br />

in both the ecological and management systems<br />

throughout the animal’s range, there are numerous<br />

differences. <strong>The</strong>se similarities and distinctions<br />

are enumerated and discussed in detail in the later<br />

sections of the Report. <strong>The</strong> table on p.7 is an effort<br />

to summarize the nature of the fishery and its<br />

management in each of the five jurisdictions, and<br />

to set the stage for the more detailed discussions<br />

that follow.<br />

ALASKA SPOT PRAWN FISHERY<br />

Biological Status of <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong>s<br />

Southeastern Alaska historically has been<br />

described as the “shrimp treasure house” (Brian<br />

Paust, University of Alaska Marine Advisory<br />

Program. Pers. comm., June 2001). While other<br />

regions—such as Prince William Sound, Kachemak<br />

Bay, and the waters off the coast of Kodiak Island—<br />

once supported spot prawn populations large<br />

enough to sustain a commercial harvest, this is no<br />

longer the case. Southeastern Alaska is now the<br />

locus of spot prawn commercial activity. (Please<br />

note: For the purposes of the Status Report, the<br />

“Alaska” section will focus primarily on the southeastern<br />

Alaska spot prawn fishery.)<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> prawns remain “cryptic” organisms whose<br />

long-term sustainability and appropriate harvest<br />

are challenged by this lack of basic biological<br />

information (Paust, University of Alaska Marine<br />

Advisory Program. Pers. comm., June 2001). At<br />

this stage, data suggest that many different areas<br />

and subpopulations of a greater metapopulation<br />

exist in the region (Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., February<br />

2001). A stated goal of management is to further<br />

this biological understanding of spot prawn<br />

abundance and distribution.<br />

Analysis of preliminary research suggests that spot<br />

prawns in southeastern Alaska may be vulnerable<br />

to serial depletion. However, results are still under<br />

review, and the data are inconclusive. Whether serial<br />

depletion is due to changing environmental conditions<br />

or the effects of fishing is not currently known<br />

(see Piatt and Anderson 1996 in Orensanz et al. 1998).<br />

In the 1960s and ’70s, the Alaska Department<br />

of Fish and Game (ADFG) collected limited catchdistribution<br />

and pot-efficiency data. A 1996 review<br />

of catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) data available<br />

through fish tickets led to a recognition that the<br />

amount and type of biological data available were<br />

inadequate for effective spot prawn management.<br />

A stock assessment protocol to gather more information<br />

was developed, and a multi-year pilot study<br />

to obtain CPUE, size and weight, and size and sex<br />

data was begun in <strong>Fishery</strong> Management Districts 3<br />

and 7 prior to the 1996–97 fishery. <strong>The</strong> goal of this<br />

study was to: “collect and evaluate data required for<br />

rational management, to understand the variability<br />

of various parameters associated with stock assessment,<br />

to investigate factors essential to establishing<br />

an appropriate stock assessment program, and to<br />

provide information necessary to develop a well

founded [harvest rate] management plan in the<br />

near future” (Koeneman and Botelho 2000c).<br />

Further research was carried out prior to the 1997–<br />

98 season, including the first pre-season survey in<br />

District 3, in-season monitoring of the fishery, and<br />

dockside sampling of landed catch. More recently,<br />

research utilizing pre- and post-season surveys<br />

has increased in major fishing districts. Plans exist<br />

to carry out additional post-season surveys and<br />

further develop an abundance index in at least<br />

two fishing districts by 2001–02. Dockside sampling<br />

is currently carried out in the most heavily harvested<br />

fishing districts, and monitoring and sampling<br />

takes place on the fishing grounds during commercial<br />

openings (Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., May 2001).<br />

On-board and dockside sampling programs allow<br />

additional biological data to be collected.<br />

An Overview of Management<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

Survey data are used to develop indices of abundance<br />

and to define population parameters such<br />

as length frequency, sex composition, and fecundity<br />

for spot prawns in surveyed districts. It must be<br />

noted that these surveys are limited in number<br />

and geographic scope and represent a relatively<br />

short time series. Integrating the multitude of factors<br />

that influence production of spot prawns into<br />

a sustainable management system will take time<br />

and a continued commitment to understanding<br />

the ecological dynamics of this species (Love,<br />

ADFG. Pers. comm., February 2001).<br />

History of the <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

Pot fisheries for shrimp historically have concentrated<br />

in Cook Inlet for coonstripe shrimp (Pandalus<br />

danae), and in Prince William Sound and<br />

southeastern Alaska for spot prawns. Harvest<br />

records indicate that effort in these fisheries was<br />

Alaska British Columbia Washington Oregon California<br />

Years in the <strong>Fishery</strong> ±30 ±87 ±60 ±8 ±31<br />

Total Catch (lbs/1999)* 800,000 3.1 million 228,375 22,221 615,000<br />

Pot/Trap Catch 800,000 3.1 million 127,049* 752 201,096<br />

Trawl Catch N/A N/A 96,250 21,459 413,658<br />

Pot Only <strong>Fishery</strong> YES YES YES (inshore) NO NO<br />

Total Catch Limits YES NO YES NO NO<br />

Daily Catch Limits NO YES∞ YES (non-Tribal) NO NO<br />

Number of Vessels 310^ 257¥ 26∆ (non-Tribal) 16µ 97<br />

Limits on Entry YES YES YES (non-Tribal) YES NO≠<br />

Seasonal Closures YES YES YES NO YES<br />

Area Closures YES YES YES NO YES‡<br />

Daylight-Only Fishing YES YES YES (inshore) NO NO<br />

Size Limits YES YES YES (inshore) NO NO<br />

Trawl-Excluder Device N/A N/A YES YES YES<br />

Trawl-Mesh Restrictions N/A N/A YES YES YES<br />

Pot/Trap Limits YES YES YES YES YES<br />

Pot Destruct Device YES YES YES NO YES<br />

Fish Tickets/Logs YES YES YES YES YES<br />

Observer Coverage YES# YES NO NO NO@<br />

CPUE Data YES YES YES NO YES<br />

Stock Assessment NO NO NO NO NO<br />

Surveys YES YES YES NO NO<br />

Spawner Index NO YES NO NO NO<br />

Management Plan YES YES YES (inshore) NO NO<br />

* Excluding Hood Canal tribal catch.<br />

∞ Only the recreational fishery is subject to daily catch limits.<br />

^ 310 permits are allowed in the fishery. In 1999, 183 permits were fished. In the 2000–1 season, 168 permits registered to fish.<br />

¥ <strong>The</strong>re are 253 commercial licenses and 4 communal (Aboriginal) licenses in the fishery. Not all licenses are fished in a given year.<br />

∆ This is an estimate of vessels in the inshore and offshore fishery. <strong>The</strong> inshore fishery (non-Tribal) is limited to 18 licenses. <strong>The</strong> offshore<br />

fishery (non-Tribal) is limited to 15 licenses: 10 pot and 5 trawl.<br />

µ Total of 6 trawl permits and 10 trap permits are allowed in the fishery.<br />

≠ A Restricted Access Program is presently being developed for the trap fishery.<br />

‡ <strong>The</strong>re are no trap area closures at the present time.<br />

# Observer coverage is required only on floating processors. <strong>The</strong> owner pays for observer coverage.<br />

@ An observer program was instituted in 2000. Coverage is 2% of the trap fleet and 2% of the trawl fleet.<br />

7

8<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

sporadic, with low harvests. This is probably due<br />

to the fact that spot prawns historically were a<br />

supplemental source of income for salmon and<br />

halibut fishers (Koeneman and Botelho 2000c).<br />

Limited data from the 1960s suggest an annual<br />

harvest of 7,938 kilograms (17,464 lbs.) with a<br />

record catch of 17,690 kilograms (375,219 lbs.).<br />

Management was “passive” and markets existed<br />

for whole, fresh product or fresh tails.<br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn fishery became increasingly important<br />

to the fishing industry in the 1980s, with a<br />

resulting increase in both effort and landings.<br />

Average annual landings peaked at 170,554 kilograms<br />

(375,219 lbs.), and in the 1988–89 season<br />

130 permits were fished. In Prince William Sound<br />

the number of vessels participating in the fishery<br />

expanded ninefold between 1978 and 1987, with<br />

catches peaking in 1986 and then dropping precipitously,<br />

in part due to the Exxon Valdez oil spill.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fishery in Prince William Sound was closed<br />

by emergency order in 1990 due to low stock<br />

abundance. Experimental fishing in late 1991<br />

indicated “severely depressed stocks”; the fishery<br />

was closed in 1992 and remains closed today<br />

(Orensanz et al. 1998).<br />

Southeastern Alaska’s spot prawn catches were<br />

relatively small and the pace of fishing slow until<br />

the 1996–97 fishing season. Management reflected<br />

the nature of the fishery at that time. It was primarily<br />

“passive,” restricting only the number of pots<br />

fished and the mesh size used. Little funding or<br />

need for “active” management existed. <strong>The</strong> combination<br />

of growth in fishing effort, changing market<br />

conditions, and technological improvements drove<br />

commercial activity farther offshore or into other<br />

fishing areas. At this point, it became clear to management<br />

that a more structured management system<br />

was needed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Pot <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> spot prawn fishery grew rapidly in the 1990s,<br />

when up to 248 permits were fished and catches<br />

peaked at 356,076 kilograms (783,367 lbs.). Extensive<br />

regulations were established at this time. Total<br />

season harvest from all districts was restricted at<br />

371,952 kilograms (818,294 lbs.). Mesh-size limits<br />

were set in order to allow the escape of prawns<br />

that were smaller than 30 mm (1.18 in.) in carapace<br />

length. <strong>The</strong> fishing season was restrained in<br />

order to prevent fishing during the egg-hatching<br />

period (varies geographically, but typically falls<br />

between late February and mid-May) and during<br />

the summer, when prawns molt and their shells<br />

are soft. In 1997, a fishing season of October 1 to<br />

February 28 was implemented.<br />

In late 1994 the first catcher-processor 4 came<br />

into the fishery, and in the 1995–96 season five<br />

floating-processors 5 and additional catcherprocessors<br />

participated. Pot catch efficiency and<br />

the pace of the fishing greatly increased at this<br />

time. <strong>The</strong>re was a shift from “tailed” to unsorted,<br />

whole product resulting in a moderate increase<br />

in value. <strong>The</strong> change in preferred product was significant<br />

in that it allowed fishers to spend less time<br />

sorting and processing prawns, and more time<br />

pulling pots or processing frozen-at-sea (FAS)<br />

product. <strong>The</strong> spot prawn fishery then became<br />

a major source of income for many fishers.<br />

Overcapitalization concerns led to discussions<br />

about the development and implementation of a<br />

limited-entry program to control effort and capacity.<br />

<strong>The</strong> limited-entry program was announced in<br />

late 1995 and established in 1996. Participation<br />

was restricted to 332 permits, the first of which<br />

were issued in February 1998. <strong>The</strong> announcement<br />

of this program led to speculative fishing behavior,<br />

and the actual number of permits fished peaked at<br />

353 in 1995. As a result, the ability of the program<br />

to actually control fishing effort was directly affected.<br />

To date, 309 permits have been issued: 155 transferable,<br />

154 non-transferable. For the 2000–01 fishing<br />

season, 168 permits to fish were registered.<br />

Guideline Harvest Levels 6 (GHLs) were instituted<br />

in 1997 for southeastern Alaska’s fishing districts.<br />

<strong>The</strong> GHLs were based on historical catches from<br />

the 1990–91 to 1994–95 fishing seasons. Due to the<br />

fact that GHLs are based on historical catch records,<br />

managers believe that they may not relate to such<br />

biological parameters as spawner abundance or<br />

recruitment strength. This is especially the case in<br />

southeastern Alaska, where the GHLs are based on<br />

only five years of data from a fishery that continues<br />

to exhibit increases in fishing effort and efficiency.<br />

Similarly, catch-per-unit-effort data may not<br />

reflect the fishery’s actual biomass. Improvements<br />

__________________________________________________________<br />

4 Catcher-processors are defined in Alaska Commercial Fishing<br />

Regulations (2000–2002) as “a vessel from which shrimp are caught and<br />

processed on board that vessel and from which no shrimp caught on<br />

other vessels was purchased or processed” (p. 84).<br />

5 A floating-processor is defined by the Alaska Commercial Fishing<br />

Regulations (2000–2002) as “a vessel that purchases and processes<br />

shrimp delivered to it by other vessels” (p. 85).<br />

6 <strong>The</strong> Alaska Commercial Fishing Regulations (2000–2002) define<br />

Guideline Harvest Levels as the “preseason estimated level of allowable<br />

fish harvest which will not jeopardize the sustained yield of the<br />

fish stocks” (p. 63).

in fishing techniques and technology can continue<br />

to ensure good catch rates even if stock abundance<br />

is, in fact, decreasing. In order to achieve sustainable<br />

spot prawn management, ADFG’s goals are<br />

to avoid basing the fishery on single-year or size<br />

classes, and to manage on a sustained-yield basis<br />

(Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., May 2001).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Shrimp Trawl <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Alaskan trawl shrimp fishery began in southeastern<br />

Alaska, near Petersburg, in 1915. <strong>The</strong> fishery<br />

was an otter 7 and beam 8 trawl fishery whose<br />

primary target was pink shrimp. <strong>The</strong> beam trawl<br />

fleet also targeted sidestriped shrimp (Pandalopsis<br />

dispar), and this fishery continues today. <strong>The</strong><br />

southeastern Alaska shrimp trawl fishery does<br />

not target spot prawns; spot prawns are caught<br />

only incidentally as bycatch. Southeastern Alaska<br />

was closed to otter trawling by a May 1998 Board<br />

of Fisheries decision driven primarily by conservation<br />

concerns.<br />

Nature of the <strong>Fishery</strong> Today<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Pot <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

Southeastern Alaska’s spot prawn fishery is the<br />

last significant shrimp pot fishery in the state<br />

(Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., February 2001).<br />

Although stocks may be recovering in other<br />

areas, such as the Prince William Sound fishery,<br />

these areas are still closed to spot prawn fishing.<br />

Southeastern Alaska’s fishery is primarily a smallboat<br />

fishery that includes gillnetters, trollers, and<br />

limit seiners. Baited pots are longlined or fished<br />

as single pots. Catcher-processors also are participating<br />

in the fishery in growing numbers. <strong>The</strong><br />

timely collection of harvest data is complicated<br />

due to the fact that catcher-processors remain<br />

on the fishing grounds until their holds are full.<br />

A limited-entry program characterizes the spot<br />

prawn fishery today. Guideline Harvest Levels<br />

continue to be set for each fishing district. ADFG’s<br />

emergency order process is used to close fishing<br />

districts when the GHLs are approached. If a district(s)<br />

is closed prematurely, additional emergency<br />

orders are issued and the district(s) is reopened<br />

to fishing until the full GHL is harvested.<br />

__________________________________________________________<br />

7 An otter trawl is defined by Alaska Commercial Fishing Regulations<br />

(2000–2002) as “a trawl with a net opening controlled by devices commonly<br />

called otter doors” (p. 28). A trawl is a “bag-shaped net towed<br />

through the water to capture fish or shellfish” (p. 28).<br />

8 A beam trawl is defined by Alaska Commercial Fishing Regulations<br />

(2000–2002) as “a trawl with a fixed net opening utilizing a wood or<br />

metal beam” (p. 28).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> prawn pounds per delivery and pounds<br />

caught per permit are increasing, as are the number<br />

of permits actively fished. Based on analysis<br />

of survey data, a 2.0 tail-weight conversion was<br />

recently adopted in the fishery. <strong>The</strong> purpose of<br />

the conversion factor was to more accurately<br />

reflect the total spot prawn biomass removed<br />

by commercial fishing. Approximately half the<br />

total weight of a spot prawn is its head; the other<br />

half is its tail. Application of the conversion factor<br />

increased GHLs in nearly all the fishing districts.<br />

Increased GHLs have not translated into a slower<br />

rate of harvest. This is largely due to continued<br />

growth in fishing effort and efficiency, and an<br />

increase in the number of previously unfished<br />

permits being fished. Last season’s GHLs were<br />

caught in less than a month in most of the 16<br />

fishing areas, and in one week or less in certain<br />

districts (Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., February<br />

2001). In the face of decreasing season length,<br />

management information must be swiftly collected<br />

and summarized to keep up with management<br />

needs. Fishers processing and freezing their catch<br />

on board must now report their total catch weekly<br />

in all fishing districts. In addition, daily fish tickets<br />

must be filled out, and these must match the<br />

weekly reported total.<br />

Management is based on closed spring and summer<br />

seasons to prevent fishing during the egg-hatch<br />

and growth period. Minimum mesh restrictions<br />

have been implemented to ensure that only larger<br />

animals are retained. Two different pot sizes have<br />

been approved, with restrictions on the number<br />

of pots per vessel based on which size class is used.<br />

Fishing is further regulated through limited daily<br />

deployment and hauling times. <strong>The</strong> permitting of<br />

floating-processors is regulated, and all vessels are<br />

required to carry on-board observers. (See “Existing<br />

Management and Regulatory Systems,” below, for<br />

details of these management restrictions.)<br />

ADFG is expanding its shrimp management and<br />

research program. Management data are acquired<br />

through fish ticket data, limited pre- and postseason<br />

surveys, and on-board and dockside catchsampling<br />

programs. On-board sampling during<br />

the fishing season was first instituted in 1999<br />

and is being expanded, as is the number of areas<br />

surveyed. In January 2000, the Board of Commercial<br />

Fisheries adopted the Southeast Alaska Pot<br />

Shrimp Management Plan, mandating that spot<br />

prawns be managed on a “sustained yield” basis<br />

(Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., May 2001).<br />

9

10<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

<strong>The</strong> 1999–2000 spot prawn fishery was characterized<br />

by:<br />

•a strong market for whole prawns with an<br />

approximate value of $4 million<br />

•a growing number of catcher-processors<br />

participating<br />

•an increasing number of permits fished<br />

•an increase in total pounds caught per permit<br />

•an increase in pounds per landing<br />

•a majority of fishing districts being harvested<br />

within one month<br />

Today’s management and conservation concerns<br />

fall into two broad categories: the potential for<br />

overfishing and the potential for overcapitalization.<br />

<strong>The</strong> risk of overfishing stems from the following<br />

factors:<br />

•GHLs are not based on current estimates of<br />

population abundance<br />

•size-specific harvesting; i.e., the retention of<br />

the larger, more valuable (in both economic and<br />

biological terms) females<br />

•potential for serial stock depletion<br />

<strong>The</strong> potential for overcapitalization of the fishery<br />

arises from the following factors:<br />

•increasing number of permits actively fished<br />

•increasing number of catcher-processors<br />

participating in the fishery<br />

•increasing intensity and efficiency of the fishery<br />

<strong>The</strong> Shrimp Trawl <strong>Fishery</strong><br />

Annual shrimp trawl harvests have fallen steadily;<br />

prime fishing areas (Cook Inlet, Kodiak, and the<br />

Alaska Peninsula) are now closed due to depleted<br />

stocks. Pink shrimp are still the primary target of<br />

the trawl fishery (otter trawls are banned in southeastern<br />

Alaska), constituting approximately 80%<br />

of trawl landings by weight.<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> prawns are landed only incidentally in<br />

Alaska’s shrimp trawl fisheries. Comparatively<br />

few adult spot prawns are harvested by trawl gear,<br />

as the beam trawlers do not fish the rocky habitats<br />

preferred by adult spot prawns. Smaller spot<br />

prawns (juveniles), which can be found in softbottom<br />

habitats, are occasionally caught in beam<br />

trawls (Love, ADFG. Pers. comm., May 2001).<br />

Approximately 1,029,382 kg. (2,264,641 pounds)<br />

of shrimp were landed in the 1998–99 fishing season.<br />

It is estimated that the harvest was made up<br />

of “only a trace of spot prawns” (Koeneman and<br />

Botelho 2000b). Through November 1999 of the<br />

1999–2000 fishing season, 829,183 kg. (1,824,203<br />

pounds) of shrimp had been landed—2,409 kg.<br />

(5,300 pounds) was spot prawns.<br />

Recreational, Subsistence, and Personal Use<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Fisheries<br />

<strong>The</strong> recreational, subsistence, and personal use<br />

fisheries, specifically for spot prawns, are regulated<br />

but not closely monitored in Southeastern<br />

Estimated Recreational/Personal Use Harvests of Shrimp in Gallons in Southern<br />

Alaska as Estimated from the Statewide Harvest Mail Survey, 1992–1999<br />

Source: Paul Suchanek, ADFG

Alaska (Paul Suchanek, ADFG. Pers. comm., April<br />

2001). <strong>The</strong> Board of Fisheries (BOF) has made several<br />

decisions regarding these fisheries in recent<br />

years. In District 13, the BOF adopted a “customary<br />

and traditional use finding” for shrimp and<br />

subsistence use, giving it priority over other uses.<br />

In addition, the BOF has implemented closures<br />

near coastal communities to protect subsistence<br />

and personal use.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are very limited data regarding recreational,<br />

subsistence, or personal use fisheries for spot<br />

prawns. <strong>The</strong> total number of participants and<br />

the amount of annual removals are not known.<br />

Estimates of recreational and personal use shrimp<br />

harvests are developed through an ADFG mail<br />

survey. <strong>The</strong>se estimates refer to all shrimp species.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no estimate of what percentage of the<br />

total shrimp harvest is spot prawns.<br />

Large annual variations in the recreational and<br />

personal use harvests are due in part to relatively<br />

poor estimates of sample size. It is likely that a<br />

small number of shrimpers in each area catch a<br />

large proportion of the overall catch. If these<br />

shrimpers were the ones who were contacted and<br />

responded to the survey, the estimate for the year<br />

would probably be high. Conversely, if these indi-<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

Estimated recreational/personal use harvests of shrimp (numbers) and boat-days and pots of<br />

shrimping effort in the Ketchikan marine fishery as estimated by an on-site creel survey during<br />

late April or early May through late September, 1988–2000.<br />

Source: Paul Suchanek, ADFG<br />

viduals were not included in the sample, then that<br />

year’s harvest estimate would be low (Suchanek,<br />

ADFG. Pers. comm., April 2001).<br />

ADFG also conducts a summer creel survey in<br />

Ketchikan aimed at estimating the total shrimp<br />

harvested. This survey also suggests highly variable<br />

recreation and personal use harvests. Analysis<br />

of the creel survey estimates total shrimping effort.<br />

In Ketchikan, the shrimp effort constitutes approximately<br />

30% of the boat-days of shellfish effort;<br />

the remaining 70% of boat-days target crab<br />

(Suchanek, ADFG. Pers. comm., April 2001).<br />

Landings, Landed Values,<br />

and Markets<br />

Between 1994 and 2000, pot landings ranged from<br />

486,678 kg. (1,070,691 pounds) in the 1994–95 season<br />

to an estimated 363,636 kg. (800,000 pounds)<br />

in 1999–2000. <strong>The</strong> number of permits fished<br />

peaked prior to the implementation of limited<br />

entry in 1994–95, but fell to 183 in 1999–2000.<br />

<strong>The</strong> number of permits registered increased for<br />

the 2000–01 fishing season, but the number of<br />

permits actually fished is not yet available.<br />

An increasing number of catcher-processors participated<br />

in the 1999–2000 fishing year, while float-<br />

11

12<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong>: A Status Report<br />

ing-processors were not in evidence on the fishing<br />

grounds. Participation by catcher-processors seems<br />

to be increasing, with approximately 60% of the<br />

fleet now having freezers on-board (Love, ADFG.<br />

Pers. comm., May 2001). Catcher-processor numbers<br />

appear to have increased again for the 2000–<br />

01 season, but these data have yet to be confirmed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ex-vessel value of the fishery at the close of<br />

the 1999–2000 season was estimated at $2.8 million.<br />

Markets remained strong for spot prawns in<br />

2000 and prices were high, but prospects for 2001<br />

appear to have softened as the Japanese economy<br />

continues to slip and the average Japanese income<br />

declines. Markets for spot prawns are cyclical and<br />

considered fluid; fluctuations are not unexpected.<br />

<strong>The</strong> majority of product in the fishery are whole,<br />

sorted, dipped, and frozen-at-sea (FAS) prawns,<br />

which are estimated to sell for $8.00/lb. wholesale<br />

(whole weight), and as high as $70.00/lb. in restaurants.<br />

This year there has already been a 30% decline<br />

in unit price, indicative of the volatility of both the<br />

price and markets for spot prawns (Stephen Wong,<br />

SeaPlus. Pers. comm., June 2001).<br />

<strong>The</strong> frozen-at-sea product type is considered<br />

sashimi grade. Over 90% is sold to Japan. Frozen<br />

spot prawns constitute less than 1% of total<br />

Japanese shrimp imports (Wong, SeaPlus. Pers.<br />

comm., June 2001). According to SeaPlus, which<br />

buys both Alaskan and Canadian spot prawns<br />

(40:60), the US market constitutes 5–10% of spot<br />

prawn production. California is the primary US<br />

market, but product is also sold in Chicago,<br />

Detroit, Denver, Atlanta, and Florida.<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> prawns are the “species of choice” for the<br />

Asian live markets. Fishers throughout southeastern<br />

Alaska devote at least part of their fishing time<br />

to serving the live market (Paust, University of<br />

<strong>Spot</strong> <strong>Prawn</strong> Product<br />

Photo Courtesy Stephen Wong, SeaPlus Marketing.<br />

Alaska Marine Advisory Program. Pers. comm.,<br />

June 2001). While the live market is definitely a<br />

high-value market, it is a difficult one to capture.<br />

<strong>The</strong> difficulty, primarily logistical, is due to the<br />

complexity and economics of organizing transportation<br />

and shipping. SeaPlus’ Stephen Wong<br />

said, “Shipping live in volume is an impossibility.<br />

<strong>The</strong> difficulty of establishing effective transportation<br />

linkages poses an enormous risk. <strong>The</strong> profits<br />

from the live market just aren’t great enough to<br />

take that risk.” It is also problematic due to the<br />

possibility of transporting diseases, some of<br />

which may not even have been identified, to<br />

other regions and countries (Love, ADFG. Pers.<br />

comm., June 2001).<br />

Existing Management and<br />

Regulatory Systems<br />

Alaska’s Management Philosophy<br />

<strong>The</strong> Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division<br />

of Commercial Fisheries, oversees management<br />

and conservation of Alaska’s commercial fisheries.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> mission of the Division of Commercial<br />

Fisheries is to manage, protect, rehabilitate,<br />

enhance, develop fisheries and aquatic plant<br />

resources in the interest of the economy and<br />

general well-being of the State, consistent<br />

with the sustained yield principle and subject<br />

to allocations established through the public<br />

regulatory processes. <strong>The</strong> Division is responsible<br />

for the management of the State’s commercial,<br />

subsistence, and personal use fisheries;<br />

the rehabilitation and enhancement<br />

of existing fishery resources; and the development<br />

of new fisheries. Technical support is<br />

provided to the private mariculture and<br />

salmon ranching industries. <strong>The</strong> Division also<br />

plays a major role in the management of fisheries<br />

in the 200-mile Exclusive Economic<br />

Zone and participates in international fisheries<br />

negotiations.”<br />

(See http://www.cf.adfg.state.ak.us/cf_home.htm)<br />

Regulations, particularly those governing allocation,<br />

are determined by the Alaska Board of<br />

Fisheries, based on recommendations from ADFG<br />

and testimony from commercial, recreational, personal<br />

use, and subsistence users. <strong>The</strong> BOF members<br />

are appointed by the Governor and approved<br />

by the legislature.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Southeastern Alaska Pot Shrimp<br />

Management Plan<br />

<strong>The</strong> Board of Fisheries implemented a manage-

ment plan for spot prawns in January 2000. <strong>The</strong><br />

Southeastern Alaska (Registration District A) Pot<br />

Shrimp Management Plan directs the ADFG to<br />

manage spot prawns (and coonstripe shrimp)<br />

for “sustained yield” in order to:<br />

•Maintain a number of age classes of prawns that<br />

will ensure the long-term viability of the stock<br />

and reduce the dependence on annual recruitment<br />

•Reduce fishing periods for prawn stocks during<br />

the biologically sensitive periods of the life cycle<br />

(e.g., egg hatch, growth, recruitment) and when<br />

the stocks are in poor quality for the market<br />

•Reduce the mortality of any small shrimp<br />

[prawns] of any species<br />

•Maintain an adequate brood stock for the<br />

rebuilding of prawns should it be necessary<br />

•Continue the development of prawn fisheries in<br />

districts where effort has been low or sporadic<br />

•Re-open prawn fisheries by emergency order<br />

during the period May 15–July 31 in areas where<br />

the Guideline Harvest Range has not been<br />

reached during the established winter fishing<br />

season<br />

•Revise the Guideline Harvest Ranges to reflect a<br />

conversion of the tail weight to the whole weight<br />

by applying a factor of 2.00<br />

Summary of Commercial Management and<br />

Regulatory Measures<br />

Alaska’s management activities are defined by a<br />

complex set of regulatory measures and statutory<br />

law. This section provides an overview of some of<br />

the central elements of this system. It is not an<br />

exhaustive or definitive investigation of spot<br />

prawn regulation, management, and law in Alaska.<br />

For a complete description of the State’s existing<br />

shellfish management regime, see the 2000–2002<br />

ADFG Commercial Shellfish Fishing Regulations<br />

booklet.<br />

•<strong>The</strong> spot prawn pot fishery has been limited<br />

entry since 1997, with the number of allowable<br />

permits constrained to 310.<br />

•All prawn regulations apply in shrimp prawn<br />

registration areas, and, where applicable, in<br />