Life History of Emerita analoga (Stimpson) (Anomura, Hippidae) in a ...

Life History of Emerita analoga (Stimpson) (Anomura, Hippidae) in a ...

Life History of Emerita analoga (Stimpson) (Anomura, Hippidae) in a ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Estuar<strong>in</strong>e, Coastal and Shelf Science (1999), 48, 101–112<br />

Article No. ecss.1998.0396, available onl<strong>in</strong>e at http://www.idealibrary.com on<br />

<strong>Life</strong> <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (<strong>Stimpson</strong>)<br />

(<strong>Anomura</strong>, <strong>Hippidae</strong>) <strong>in</strong> a Sandy Beach <strong>of</strong> South<br />

Central Chile<br />

H. Contreras a , O. Defeo b,c and E. Jaramillo a<br />

a Instituto de Zoología, Universidad Austral de Chile, Casilla 567, Valdivia, Chile<br />

b CINVESTAV-IPN Unidad Mérida, A.P. 73 Cordemex, 97310 Mérida, Yucatán, México<br />

c Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Constituyente 1497, 11200 Montevideo, Uruguay<br />

Received 10 March 1998 and accepted <strong>in</strong> revised form 13 July 1998<br />

<strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (Crustacea, <strong>Anomura</strong>, <strong>Hippidae</strong>) is a characteristic species <strong>of</strong> the swash zone <strong>of</strong> temperate sandy beaches<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Eastern Pacific. To analyse the reproductive biology and population dynamics <strong>of</strong> a population located <strong>in</strong> south<br />

central Chile, monthly samples were collected from an exposed sandy beach (Mehuín, c. 39S). Samples were taken from<br />

June 1989 through May 1991, and between June 1992 and May 1993, from the uppermost beach levels and the lowest<br />

level <strong>of</strong> the swash zone. The highest abundances <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> occurred dur<strong>in</strong>g the late spr<strong>in</strong>g–early summer. The highest<br />

mean fecundity values occurred <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter and summer, and the lowest dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g. The size at which females reach<br />

sexual maturity was found to be 16–17 mm (about 12 months after recruitment). Two recruitment peaks were found: one<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g early autumn, and the other dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g. Growth analyses showed that growth rates <strong>of</strong> females were higher than<br />

those <strong>of</strong> males for the three annual periods analysed. It is concluded that differences <strong>in</strong> size at sexual maturity and <strong>in</strong><br />

growth rates can expla<strong>in</strong> sexual dimorphism <strong>in</strong> adult E. <strong>analoga</strong> <strong>in</strong> south central Chile. 1999 Academic Press<br />

Keywords: <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong>; sandy beaches; Chile<br />

Introduction<br />

The anomuran decapod <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (<strong>Stimpson</strong>) is<br />

a widespread and abundant crustacean <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g<br />

exposed sandy beaches on the east coast <strong>of</strong> the Pacific<br />

Ocean. Its geographical distribution primarily spans<br />

a region stretch<strong>in</strong>g from the Kodiak Islands <strong>in</strong><br />

Alaska (58N) to the extreme south coast <strong>of</strong> Chile<br />

(55S) be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terrupted <strong>in</strong> tropical regions and those<br />

with temperatures above 20C (Efford, 1969; Nuñez<br />

et al., 1974). Various authors have studied both the<br />

northern and southern hemisphere populations. For<br />

example, Cox and Dudley (1968), Wenner (1972),<br />

Wenner and Haley (1981), Dugan et al. (1991) and<br />

Wenner et al. (1993) have analysed reproductive<br />

aspects, whilst MacG<strong>in</strong>itie (1938), Efford (1965) and<br />

Cubit (1968) have studied the spatial distribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> the species, and related this variability to physical<br />

(Barnes & Wenner, 1968; Cubit, 1968; Perry, 1980;<br />

Dugan et al., 1991) and biological factors (Efford,<br />

1965; Perry, 1980).<br />

E. <strong>analoga</strong> has <strong>in</strong>direct development. Eggs are carried<br />

by the females on their pleopods (Johnson &<br />

Lewis, 1942). Under laboratory conditions, the <strong>in</strong>cubation<br />

period is estimated to be between 29 and 32<br />

days (Boolotian et al., 1959). This is followed by a<br />

planktonic larval stage last<strong>in</strong>g between 3 and 4 months<br />

(Johnson, 1939). The species reproduces all year<br />

round, as egg-bear<strong>in</strong>g females are found throughout<br />

this period <strong>in</strong> the saturation zone <strong>of</strong> sandy beaches<br />

(Boolotian et al., 1959; Osorio et al., 1967; Cox &<br />

Dudley, 1968; Perry, 1980); however, the period <strong>of</strong><br />

peak reproductive activity is reached <strong>in</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g–<br />

summer. Osorio et al. (1967), Efford (1969) and<br />

Wenner et al. (1987a) found a significant positive<br />

correlation betwen female size and fecundity (number<br />

<strong>of</strong> eggs carried). Dugan et al. (1991, 1994) showed<br />

significant geographic variations <strong>in</strong> fecundity <strong>of</strong> E.<br />

<strong>analoga</strong> which were related to physical variability <strong>in</strong><br />

sandy beaches <strong>of</strong> California. Wenner et al. (1987)<br />

found variations <strong>in</strong> fecundity which were related to<br />

size/age <strong>of</strong> females.<br />

In south central Chile (c. 39–41S), E. <strong>analoga</strong> is a<br />

conspicuous <strong>in</strong>habitant <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>termediate and dissipative<br />

sandy beaches (Jaramillo et al., 1993). However,<br />

limited <strong>in</strong>formation is available concern<strong>in</strong>g its<br />

reproductive biology and population dynamics. Thus,<br />

the aim <strong>of</strong> this study was to analyse the reproductive<br />

biology, fecundity, growth and recruitment <strong>of</strong> E.<br />

<strong>analoga</strong> on an exposed sandy beach located at Mehuín<br />

0272–7714/99/010101+12 $30.00/0 1999 Academic Press

102 H. Contreras et al.<br />

20°<br />

30°<br />

40°<br />

50°<br />

(c. 39S) over a study period long enough to evaluate<br />

temporal variability <strong>in</strong> these population characteristics.<br />

Material and methods<br />

39°23'<br />

39°25'<br />

39°27'<br />

Study area<br />

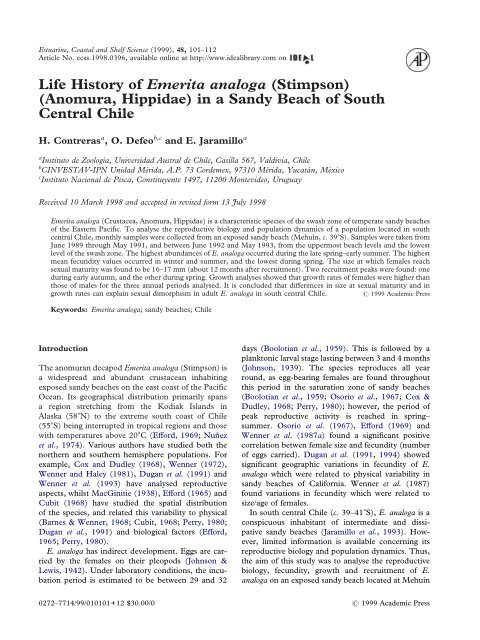

The study beach (c. 200 m long) was located at<br />

Mehu<strong>in</strong> (3926S, 7313W) on the Valdivian coast,<br />

south–central Chile (Figure 1). The beach is bounded<br />

by rocky promontories consist<strong>in</strong>g primarily <strong>of</strong> micaceous<br />

schist from which the majority <strong>of</strong> sand on the<br />

beach is formed (mostly particles between 125 and<br />

250 m, Jaramillo, 1987). Physical factors, such as<br />

wave action, tides, coastal currents and w<strong>in</strong>ds significantly<br />

affect the beach’s morphology, which experiences<br />

two marked dist<strong>in</strong>ct periods: an erosion period<br />

from mid autumn to early spr<strong>in</strong>g and an accretion<br />

period from late spr<strong>in</strong>g to early autumn (Jaramillo,<br />

1987).<br />

Sampl<strong>in</strong>g and data analysis<br />

From June 1989 to May 1991, monthly samples were<br />

taken dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g tides. Six transects were fixed<br />

perpendicular to the coast, approximately 50 m apart<br />

(Figure 1). Sampl<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts were situated along each<br />

<strong>of</strong> these transects at 10 m <strong>in</strong>tervals from the upper<br />

high tide mark to the lower level <strong>of</strong> the swash zone. As<br />

CHILE<br />

0 1 km<br />

Mehu<strong>in</strong> '<br />

Sandy beaches<br />

73°12' 73°10'<br />

LLS<br />

LLS: lowest limit <strong>of</strong> swash<br />

0 30 m<br />

Figure 1. Location <strong>of</strong> the study area at Mehuín, south central Chile. The six l<strong>in</strong>es on the rectangle <strong>of</strong> the right side show the<br />

approximate location <strong>of</strong> the six transects sampled dur<strong>in</strong>g the period June 1989–May 1991. The l<strong>in</strong>es with asterisks show<br />

the location <strong>of</strong> the two sampl<strong>in</strong>g transects (north and south side <strong>of</strong> the beach) dur<strong>in</strong>g the period June 1992–May 1993.<br />

E. <strong>analoga</strong> has a patchy distribution, this sampl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

strategy was followed to obta<strong>in</strong> a representative<br />

sample <strong>of</strong> the population on the whole beach. Because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the seasonal height fluctuations <strong>of</strong> the beach, the<br />

total number <strong>of</strong> stations on each transect varied dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the sampl<strong>in</strong>g period between 25 and 54 stations<br />

per month, with an average <strong>of</strong> 39.<br />

Additional sampl<strong>in</strong>gs were carried out between June<br />

1992 and August 1993. Dur<strong>in</strong>g this period, just two<br />

transects were sampled (north and south ends <strong>of</strong> the<br />

beach; Figure 1). Ten equidistant sampl<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts<br />

were arranged along each transect. The second station<br />

was located at the high tide mark and the last at the<br />

lowest swash level. Three 0·03 m 2 replicates were<br />

taken <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong> these stations and the animals collected<br />

from each replicate were transferred to the<br />

laboratory for sex<strong>in</strong>g and measurement.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g both sampl<strong>in</strong>g periods, the samples were<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g a plastic cyl<strong>in</strong>der (20 cm <strong>in</strong> diameter)<br />

buried to a depth <strong>of</strong> approximately 25 cm. The sediment<br />

was sieved through a 1000 m mesh and the<br />

animals reta<strong>in</strong>ed preserved <strong>in</strong> 10% formal<strong>in</strong>. Individuals<br />

were measured us<strong>in</strong>g the length <strong>of</strong> the cephalothorax<br />

(thus, Lc=body size) i.e. from the tip <strong>of</strong> the<br />

rostrum to the distal scoop <strong>of</strong> the cephalothorax. The<br />

smallest <strong>in</strong>dividuals (i.e. Lc

Mean abundance per 0.03 m 2 (X ± 1 s.e.)<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

12<br />

8<br />

4<br />

0<br />

Total<br />

J A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

J A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

J A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

Ovigerous<br />

J A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

Juveniles<br />

J A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

89<br />

90 91 92 93<br />

Figure 2. Temporal variability <strong>in</strong> the abundance <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g both study periods: June 1989–May 1991 and June<br />

1992–May 1993.<br />

%<br />

%<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

J<br />

J<br />

Ovigerous<br />

A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

Juveniles<br />

A O D F A J A O D F A J A O D F A<br />

89<br />

90 91 92<br />

93<br />

<strong>Life</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> 103<br />

Figure 3. Temporal variability <strong>in</strong> the abundance (expressed as percentage <strong>of</strong> the total population) <strong>of</strong> ovigerous females and<br />

juveniles <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g both study periods.

104 H. Contreras et al.<br />

Egg numbers<br />

Egg numbers<br />

Egg numbers<br />

Egg numbers<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1 15<br />

1 15<br />

1 15<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

W<strong>in</strong>ter '89<br />

20 25 30<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>g '89<br />

20 25 30<br />

Summer '90<br />

20 25 30<br />

Autumn '90<br />

1 1<br />

15 20 25 30 35<br />

15 20 25 30 35<br />

Carapace length (mm)<br />

Figure 4. Correlations between the number <strong>of</strong> eggs and body size <strong>of</strong> ovigerous females <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> for each seasonal period.<br />

Results <strong>of</strong> regressions are given <strong>in</strong> Table 1. Note the logarithm scale <strong>in</strong> the Y-axis.<br />

males, females without eggs (hereafter females), ovigerous<br />

females and juveniles (i.e. <strong>in</strong>dividuals smaller<br />

than 4 mm). Sexes were dist<strong>in</strong>guished on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

anatomical studies carried out by Knox and Boolotian<br />

(1963), Osorio et al. (1967) and Penchaszadeh (1971)<br />

on species <strong>of</strong> the genus <strong>Emerita</strong>. Ma<strong>in</strong> anatomical<br />

characteristics used were: (1) presence <strong>of</strong> pleopods<br />

(found exclusively <strong>in</strong> females); and (2) the genital pore<br />

position, which <strong>in</strong> females is located <strong>in</strong> the coxa <strong>of</strong> the<br />

third pair <strong>of</strong> pereopods, and <strong>in</strong> males <strong>in</strong> the fifth pair.<br />

Juveniles were those whose morphological characters<br />

were absent or difficult to recognize.<br />

35<br />

35<br />

35<br />

Egg numbers<br />

Egg numbers<br />

Egg numbers<br />

Egg numbers<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

100 000<br />

10 000<br />

1 15<br />

1 15<br />

1 15<br />

1000<br />

100<br />

10<br />

W<strong>in</strong>ter '90<br />

20 25 30<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>g '90<br />

20 25 30<br />

Summer '91<br />

20 25 30<br />

Autumn '91<br />

Fecundity analyses were carried out only for the<br />

period June 1989 to May 1991. The egg mass <strong>of</strong> each<br />

female was carefully extracted, and the diameters <strong>of</strong><br />

10 eggs were measured to estimate their volume<br />

(us<strong>in</strong>g the formula for the volume <strong>of</strong> a sphere). The<br />

total number <strong>of</strong> eggs <strong>in</strong> each mass was determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by displacement <strong>of</strong> distilled water <strong>in</strong> a graduated test<br />

tube (0·1 ml accuracy) (Diaz et al., 1983). Fecundity<br />

values were log transformed to calculate regressions<br />

between number <strong>of</strong> eggs carried by ovigerous females<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st body size. Differences <strong>of</strong> slopes and adjusted<br />

averages among regression l<strong>in</strong>es estimated for each<br />

35<br />

35<br />

35

season were analysed with ANCOVA (Sokal & Rohlf,<br />

1969).<br />

The ELEFAN Program (Electronic Length Frequency<br />

Analysis; see Gayanilo et al., 1989) was<br />

applied to the monthly composition <strong>of</strong> the population<br />

by sizes, discrim<strong>in</strong>ated by sex. The method assumes<br />

that body growth follows the von Bertalanffy Growth<br />

Equation (VGBE) (Bertalanffy, 1938). In its seasonally<br />

oscillat<strong>in</strong>g version (Hoenig & Hanumara, 1982)<br />

the VBGE has the form:<br />

Lt=L[1e [K(tt0)+(KC/2)s<strong>in</strong>2(tts) (KC/2)s<strong>in</strong>2(t0ts)] ]<br />

where:<br />

Table 1. Seasonal ranges <strong>in</strong> body size and eggs number carried by ovigerous females. Results <strong>of</strong><br />

regression analyses shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 4 and estimated fecundity for an ovigerous female with<br />

Lc=24·4 mm<br />

Season<br />

L t=length at age t<br />

L=maximum asymptotic length<br />

K=growth curvature parameter<br />

t 0=computed age at length zero<br />

C=parameter reflect<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>tensity <strong>of</strong> seasonal<br />

growth oscillation<br />

t s=start <strong>of</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>usoid growth oscillation with respect<br />

to t=0<br />

The W<strong>in</strong>ter Po<strong>in</strong>t (WP) parameter is def<strong>in</strong>ed as:<br />

WP=t s+0·5<br />

Body size<br />

(range <strong>in</strong> mm)<br />

or the time (expressed as a decimal fraction <strong>of</strong> the<br />

year) where growth is slowest (Pauly & Gaschütz,<br />

1979; Pauly et al., 1984).<br />

The ELEFAN program does not assume normality<br />

<strong>in</strong> the length frequency distributions. It uses the<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on the height and shape <strong>of</strong> the age distributions<br />

identified <strong>in</strong> the length frequency data. It<br />

identifies peaks and troughs <strong>in</strong> the samples and then<br />

fits the growth curve which passes through a maximum<br />

number <strong>of</strong> peaks (Pauly et al., 1984). An <strong>in</strong>dex<br />

Egg numbers<br />

(range) Slope Intercept n r<br />

<strong>Life</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> 105<br />

Estimated<br />

fecundity<br />

W<strong>in</strong>ter 1989 20·0–29·7 2879–17 269 0·053 2·60 70 0·68 7808·28<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>g 1989 17·9–30·1 1213–17 746 0·066 2·15 86 0·73 5919·67<br />

Summer 1990 17·8–31·0 1539–24 476 0·074 2·13 90 0·82 8818·45<br />

Autumn 1990 21·2–31·3 979–16 767 0·069 2·07 73 0·67 5639·50<br />

W<strong>in</strong>ter 1990 20·0–31·2 2062–17 277 0·059 2·29 83 0·66 5381·18<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>g 1990 16·0–31·0 691–11 737 0·061 2·16 90 0·73 4524·02<br />

Summer 1991 16·8–31·6 1033–20 374 0·074 2·07 89 0·86 7411·43<br />

Autumn 1991 18·8–30·5 1136–24 731 0·083 1·69 63 0·82 5337·55<br />

<strong>of</strong> goodness <strong>of</strong> fit, called Rn, is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the<br />

exponential form <strong>of</strong> the ESP/ASP ratio, where ESP<br />

stands for the ‘ Expla<strong>in</strong>ed Sum <strong>of</strong> Peaks ’ and ASP for<br />

‘Available Sum <strong>of</strong> Peaks ’ as (Gayanilo et al., 1989):<br />

To compare different growth rate estimates, the standard<br />

growth <strong>in</strong>dex (phi prime: Pauly & Munro,<br />

1984; Vakily, 1990) was employed as a measure <strong>of</strong><br />

overall growth performance (Sparre et al., 1989). This<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex is def<strong>in</strong>ed as:<br />

=2log 10(L)+log 10K<br />

This rationale provides a unified parameter <strong>of</strong> growth<br />

performance which does not show large variations as<br />

do K and L values (Sparre et al., 1989). Moreover,<br />

it has been used successfully as a growth <strong>in</strong>dex <strong>in</strong><br />

bivalves (Vakily, 1990; Defeo et al., 1992a). Thus,<br />

differences <strong>in</strong> growth performance between sexes and<br />

years were based on comparisons.<br />

The length <strong>in</strong>terval used to carry out the growth<br />

analysis was selected tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account the criteria<br />

outl<strong>in</strong>ed by Wolff (1989) and Sparre (1989). Class<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervals <strong>of</strong> 2 mm for males and 3 mm for females<br />

were chosen. Longevity was estimated on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

the maximum observed length derived from the relative<br />

age–length key obta<strong>in</strong>ed from length–frequency<br />

analyses.<br />

Recruitment pattern was analysed through visual<br />

<strong>in</strong>spection analyses <strong>of</strong> histograms and with the estimated<br />

growth parameters, also discrim<strong>in</strong>ated by sex,<br />

by project<strong>in</strong>g the length–frequency data backward<br />

onto the time axis (Pauly et al., 1984; Gayanilo et al.,<br />

1989). As t 0 was not available, the ord<strong>in</strong>ate scale <strong>of</strong><br />

the plot was relative, i.e. not calendar time. Normal

106 H. Contreras et al.<br />

Frequency (%)<br />

distribution patterns <strong>in</strong> recruitment were dist<strong>in</strong>guished<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the maximum likelihood approach<br />

‘ NORMSEP-Hasselblad ’ conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the FISAT<br />

Program (see Gayanilo et al., 1996 for further details).<br />

Results<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

60<br />

30<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1989<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

60<br />

30<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1990 1991<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1990<br />

0 4 8 12 16 0 4 8 12 16<br />

June<br />

July<br />

August<br />

September<br />

October<br />

November<br />

December<br />

January<br />

February<br />

March<br />

April<br />

May<br />

Body size (mm)<br />

Surf water characteristics<br />

The mean temperature <strong>in</strong> the surf water was 12·3 C<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the period June 1989 to May 1991, and<br />

12·7 C dur<strong>in</strong>g June 1992 to May 1993. Values as<br />

high as 15–17 C were registered dur<strong>in</strong>g summer<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1989 1990<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1990 1991<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

0 6 12 18 24 30 0 6 12 18 24 30<br />

August<br />

September<br />

October<br />

November<br />

December<br />

January<br />

February<br />

March<br />

Figure 5. Temporal variability <strong>in</strong> the population structure <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the study period June 1989–May 1991.<br />

June<br />

July<br />

April<br />

May<br />

months, and as low as 10–11 C dur<strong>in</strong>g w<strong>in</strong>ter months<br />

(both study periods compared). Dur<strong>in</strong>g the first study<br />

period, the mean sal<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>of</strong> surf waters was 27·8; for<br />

the second period, a mean <strong>of</strong> 28·5 was estimated.<br />

Highest sal<strong>in</strong>ity values occurred dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g–<br />

summer (up to 31–34) while the lowest usually occurred<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g w<strong>in</strong>ter months (as low as 18) (both<br />

study periods considered).<br />

Abundance<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g the sampl<strong>in</strong>g year June 1989 to May 1991,<br />

3326 E. <strong>analoga</strong> were collected: 1407 males (42·35%);

Frequency (%)<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1992<br />

0 4 8 12 16<br />

June<br />

July<br />

August<br />

September<br />

October<br />

November<br />

December<br />

February<br />

March<br />

April<br />

Body size (mm)<br />

1105 females (39·25%); 204 ovigerous females<br />

(6·14%) and 610 juveniles (18·36%). The greatest<br />

abundance <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> was observed dur<strong>in</strong>g late<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>g (November–December <strong>of</strong> 1989 and December<br />

20<br />

May<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1993 1993<br />

45<br />

January<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

45<br />

15<br />

1992<br />

0 6 12 18 24 30<br />

<strong>Life</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> 107<br />

June<br />

July<br />

August<br />

September<br />

October<br />

November<br />

December<br />

January<br />

February<br />

March<br />

Figure 6. Temporal variability <strong>in</strong> the population structure <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the study period June 1992–May 1993.<br />

April<br />

May<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1990) (Figure 2). Numbers tended to dim<strong>in</strong>ish<br />

towards the mid and late summer. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g year June 1992 to May 1993, 6035 crabs<br />

were collected: 2906 males (46·61%), 2389 females

108 H. Contreras et al.<br />

Table 2. Results <strong>of</strong> ANCOVA analyses carried out to compare seasonal regression l<strong>in</strong>es describ<strong>in</strong>g the relationships between<br />

fecundity and body size <strong>of</strong> ovigerous females<br />

Source <strong>of</strong> variation<br />

(38·32%), 97 ovigerous females (1·56%) and 843<br />

juveniles (13·52%); highest abundances dur<strong>in</strong>g this<br />

period were observed dur<strong>in</strong>g summer (December–<br />

March) and w<strong>in</strong>ter (August) (Figure 2).<br />

Males and females <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> showed their<br />

greatest abundance dur<strong>in</strong>g December <strong>of</strong> 1989 and<br />

December <strong>of</strong> 1992 (Figure 2). Dur<strong>in</strong>g the second<br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g year, males and females were also abundant<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>of</strong> 1992. Ovigerous females were<br />

collected throughout most <strong>of</strong> the study periods,<br />

usually <strong>in</strong> very low abundances (i.e. 2 <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

per 0·03 m 2 ). The exception was December 1990,<br />

when about 8 ovigerous (mean value) females per<br />

0·03 m 2 were collected. Most <strong>of</strong> the time, the ratio<br />

<strong>of</strong> males to females was 1:1, with the exception <strong>of</strong><br />

February, July, November <strong>of</strong> 1990, June, July,<br />

December <strong>of</strong> 1992 and May <strong>of</strong> 1993, when significant<br />

differences <strong>in</strong> this ratio were recorded (P

Frequency (%)<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

30<br />

15<br />

0<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

one year<br />

one year<br />

one year<br />

rates always <strong>in</strong> females as reflected <strong>in</strong> the growth <strong>in</strong>dex<br />

(Figure 8, Table 1). The W<strong>in</strong>ter Po<strong>in</strong>t (WP) was<br />

close to 0·5 (exclud<strong>in</strong>g only males 1992–1993:<br />

WP=0·8), suggest<strong>in</strong>g a consistent nadir <strong>in</strong> the growth<br />

curve <strong>in</strong> June (austral w<strong>in</strong>ter) when growth was slowest<br />

for both sexes <strong>in</strong> both analysed periods. Values <strong>of</strong><br />

parameter C were 1·0 <strong>in</strong> all calculations, imply<strong>in</strong>g<br />

heavy seasonal growth oscillations. Female longevity<br />

was nearly 4 years, while for males it was about 2 years<br />

<strong>in</strong> two <strong>of</strong> the annual periods analysed.<br />

Discussion<br />

Temporal variability <strong>in</strong> the abundance <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> at<br />

Mehuín beach showed that the highest abundances<br />

occurred dur<strong>in</strong>g late spr<strong>in</strong>g to early summer and<br />

middle autumn. Those peaks <strong>in</strong> abundances were<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

30<br />

15<br />

0<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

one year<br />

one year<br />

one year<br />

June 1989–May 1990<br />

June 1990–May 1991<br />

June 1992–May 1993<br />

Figure 7. Recruitment pattern <strong>of</strong> males and females <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> estimated by ELEFAN. The bell shaped curves <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> recruitment pulses throughout the study period.<br />

Table 3. Estimated growth parameters <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> at the beach <strong>of</strong> Mehu<strong>in</strong>, south central<br />

Chile, us<strong>in</strong>g the ELEFAN Program<br />

Period<br />

Parameters<br />

<strong>Life</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> 109<br />

1989–1990 1990–1991 1992–1993<br />

Males Females Males Females Males Females<br />

L (mm) 23·00 34·00 23·00 33·00 26·00 34·00<br />

K (l/yr) 0·48 0·60 0·60 0·80 0·31 0·68<br />

C 1·00 1·00 1·00 1·00 1·00 1·00<br />

WP 0·50 0·52 0·50 0·58 0·80 0·60<br />

2·40 2·84 2·50 2·94 2·32 2·90<br />

Rn a<br />

0·24 0·21 0·52 0·39 0·21 0·27<br />

a Goodness <strong>of</strong> fit <strong>in</strong>dex (expla<strong>in</strong>ed sum <strong>of</strong> peaks/available sum <strong>of</strong> peaks)/10 (see Gayanilo et al., 1989).<br />

primarily related to temporal variability <strong>in</strong> recruitment,<br />

which peaked at similar periods. Similar results<br />

were found by Jaramillo (1987), who studied the<br />

same beach dur<strong>in</strong>g 1978–1980. For the coast <strong>of</strong><br />

central Chile (Valparaíso, c. 35S) Conan et al. (1975)<br />

also registered two recruitment periods: June and late<br />

September. On the other hand, Osorio et al. (1967)<br />

mentioned one recruitment period dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g for<br />

E. <strong>analoga</strong> <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g a sandy beach <strong>in</strong> El Tabo (c.<br />

34S), a similar f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g to that reported by Efford<br />

(1965) for sandy beaches <strong>of</strong> California. Thus, variability<br />

<strong>in</strong> the recruitment pattern <strong>of</strong> this species along<br />

its extended geographical range seems to be quite<br />

common.<br />

Even though ovigerous females were found all year<br />

round, juveniles were absent or <strong>in</strong> very low abundances<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g some months. That could be related to

110 H. Contreras et al.<br />

Body size (mm)<br />

6 12 18 24 30 36 42<br />

Month<br />

habitat variability as discussed by Dugan et al. (1994)<br />

who found that observed trends <strong>in</strong> life history <strong>of</strong><br />

E. <strong>analoga</strong> <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g sandy beaches <strong>of</strong> California were<br />

associated with variability <strong>in</strong> water temperature, food<br />

availability and beach morphodynamics. Significant<br />

changes <strong>in</strong> beach morphodynamics have been described<br />

for Mehuín (Jaramillo, 1987) which, <strong>in</strong>deed<br />

might affect the abundance or even presence <strong>of</strong><br />

juveniles <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tertidal zone.<br />

The variability <strong>in</strong> the fecundity <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> has<br />

been related to geographic variability <strong>of</strong> physical<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> the environment (Dugan et al.,<br />

1991), age classes <strong>of</strong> females (Wenner et al., 1987a)<br />

and seasonal and local variability <strong>of</strong> food resources<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

6 12 18 24 30 36 42<br />

6 12 18 24 30 36 42<br />

48<br />

48<br />

48<br />

June 1989–May 1990<br />

June 1990–May 1991<br />

June 1992–May 1993<br />

Figure 8. Growth curves <strong>of</strong> males (solid l<strong>in</strong>e) and females (dashed l<strong>in</strong>e) <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>analoga</strong> estimated by ELEFAN from sets <strong>of</strong><br />

length frequency data <strong>of</strong> June 1989–May 1990, June 1990–May 1991 and June 1992–May 1993.<br />

(Wenner et al., 1987b). However, these studies usually<br />

represent snapshot sampl<strong>in</strong>g without annual variability.<br />

The data gathered <strong>in</strong> this study showed seasonal<br />

variations <strong>in</strong> fecundity with higher values dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

summer months.<br />

Growth rates were fastest for females dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

three annual periods analysed, as reflected by the<br />

highest values <strong>of</strong> the parameter. Moreover, dissimilar<br />

growth rates between sexes means that longevity <strong>of</strong><br />

females would be twice than that <strong>of</strong> males. Results <strong>of</strong><br />

varied slightly between annual periods, denot<strong>in</strong>g<br />

highest growth rates <strong>in</strong> 1990–1991 for both sexes.<br />

Growth rates varied seasonally <strong>in</strong> both sexes. Values <strong>of</strong><br />

the C parameter were always 1, reflect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tense

seasonal oscillations <strong>in</strong> growth. In the w<strong>in</strong>ter and early<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>g months two dissimilar <strong>in</strong>tensities <strong>in</strong> growth<br />

occurred: growth rate was practically nil dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

w<strong>in</strong>ter period and <strong>in</strong>creased abruptly dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

These seasonal oscillations suggest that growth <strong>in</strong> E.<br />

<strong>analoga</strong> would be affected by temperature differences<br />

between summer and w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>in</strong> the study area (i.e.<br />

5–6 C). Indeed, growth was m<strong>in</strong>imal from autumn to<br />

late w<strong>in</strong>ter (slowest temperatures) and <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

markedly <strong>in</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g, co<strong>in</strong>cid<strong>in</strong>g with maximum <strong>in</strong>crements<br />

<strong>of</strong> temperature. It is worth not<strong>in</strong>g that this<br />

relation between temperature and amplitude <strong>in</strong> the<br />

oscillations <strong>of</strong> growth (through the parameter C) was<br />

also observed by Arntz et al. (1987), de Alava and<br />

Defeo (1991) and Defeo et al. (1992b) for <strong>in</strong>vertebrates<br />

<strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g exposed sandy beaches <strong>of</strong> temperate<br />

latitudes <strong>in</strong> the Pacific and Atlantic coasts <strong>of</strong> South<br />

America.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We thank Marcia González, Pedro Quijón, Robert<br />

Stead, Sandra Silva, Claudia Añazco, Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Muñoz and Sonia Fuentealba for assistance dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

field sampl<strong>in</strong>g. This study was funded by CONICYT-<br />

CHILE (FONDECYT research projects 88/904 and<br />

92/191) and Universidad Austral de Chile (DID<br />

Project S92/36 and S94/30).<br />

References<br />

Arntz, W. E., Brey, T. T., Tarazona, J. & Robles, A. 1987 Changes<br />

<strong>in</strong> the structure <strong>of</strong> a shallow sandy-beach community <strong>in</strong> Peru<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>ganElNiño event. In The Benguela and comparable ecosystems.<br />

(Payne, A. I. L., Gulland, J. A. & B<strong>in</strong>k, K. H., eds). South<br />

African Journal <strong>of</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>e Science 5, 645–658.<br />

Barnes, N. B. & Wenner, A. M. 1968 Seasonal variation <strong>in</strong> the sand<br />

crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (Decapoda, <strong>Hippidae</strong>) <strong>in</strong> the Santa Barbara<br />

area <strong>of</strong> California. Limnology Oceanography 13, 465–475.<br />

von Bertalanffy, L. 1938 A quantitative theory <strong>of</strong> organic growth.<br />

Human Biology 10, 181–213.<br />

Boolotian, R. A., Giese, A. C., Farmanfarmalan, A. & Tucker, J.<br />

1959 Reproductive cycles <strong>of</strong> five west coast crabs. Physiological<br />

Zoology 32, 213–220.<br />

Conan, G., Melo, C. & Yany, G. 1975 Evaluation de la production<br />

d’una population littorale du crabe <strong>Hippidae</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong><br />

(<strong>Stimpson</strong>) par <strong>in</strong>tégration des paramétres de croissance et de<br />

mortalité. 10th European Symposium on Mar<strong>in</strong>e Biology 2, 129–<br />

150.<br />

Cox, G. W. & Dudley, G. H. 1968 Seasonal pattern <strong>of</strong> reproduction<br />

<strong>of</strong> the sand crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong>, <strong>in</strong> the Southern California.<br />

Ecology 49, 764–751.<br />

Cubit, J. 1968 Behavior and physical factors caus<strong>in</strong>g migration and<br />

aggregation <strong>of</strong> the sand crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (<strong>Stimpson</strong>). Ecology<br />

50, 118–751.<br />

de Alava, A. & Defeo, O. 1991 Distributional pattern and population<br />

dynamics <strong>of</strong> Excirolana armata (Isopoda: Cirolanidae) <strong>in</strong> a<br />

Uruguayan sandy beach. Estuar<strong>in</strong>e, Coastal and Shelf Science 33,<br />

433–444.<br />

<strong>Life</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> 111<br />

Defeo, O., Arreguín-Sanchez, F. & Sanchez, J. A. 1992a Growth<br />

study <strong>of</strong> the yellow clam Mesodesma mactroides: a comparative<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> the application <strong>of</strong> three length-based methods. Science<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e 56, 53–59.<br />

Defeo, O., Ortiz, E. & Castilla, J. C. 1992b Growth, mortality<br />

and recruitment <strong>of</strong> the yellow clam Mesodesma mactroides <strong>in</strong><br />

Uruguayan beaches. Mar<strong>in</strong>e Biology 114, 429–437.<br />

Díaz, H., Conde, J. E. & Bevilacqua, M. 1983 A volumetric method<br />

for estimat<strong>in</strong>g fecundity <strong>in</strong> decapoda. Mar<strong>in</strong>e Ecology 10, 203–<br />

206.<br />

Dugan, J. E., Hubbard, D. M. & Wenner, A. M. 1991 Geographic<br />

variation <strong>in</strong> the reproductive biology <strong>of</strong> the sand crab, <strong>Emerita</strong><br />

<strong>analoga</strong> <strong>Stimpson</strong>) on the California coast. Journal <strong>of</strong> Experimental<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e Biology and Ecology 150, 63–81.<br />

Dugan, J., Wenner, A. M. & Hubbard, D. M. 1994 Geographic<br />

variation <strong>in</strong> the life history <strong>of</strong> the sand crab, <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong><br />

(<strong>Stimpson</strong>) on the California coast: relationships to environmental<br />

variables. Journal <strong>of</strong> Experimental Mar<strong>in</strong>e Biology and<br />

Ecology 181, 225–278.<br />

Efford, I. E. 1965 Aggregation <strong>in</strong> the sand crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong><br />

(<strong>Stimpson</strong>). Ecology 34, 63–75.<br />

Efford, I. E. 1969 Egg size <strong>in</strong> the sand crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong><br />

(Decapoda, <strong>Hippidae</strong>). Crustaceana 16, 15–26.<br />

Gayanilo, F. C. Jr., Soriano, M. & Pauly, D. 1989 A draft guide to<br />

the Complete ELEFAN. ICLARM Contribution No 435, 70 pp.<br />

Gayanilo, F. C. Jr., Sparre, P. & Pauly, D. 1996 The FAO-ICLARM<br />

stock assessment tools (FISAT) user’s guide. FAO Computerized<br />

Information Series No 8. Rome, FAO, 126 pp.<br />

Hoenig, J. M. & Hanumara, R. C. 1982 A statistical study <strong>of</strong> a<br />

seasonal growth model for fishes. Tech. Rep., Dept. <strong>of</strong> Computer<br />

Science and Statistics, University <strong>of</strong> Rhode Island, K<strong>in</strong>gston.<br />

Jaramillo, E. 1987 Community ecology <strong>of</strong> Chilean sandy beaches.<br />

Ph. D. dissertation University <strong>of</strong> New Hampshire, Durham,<br />

216 pp.<br />

Jaramillo, E., McLachlan, A. & Coetzee, P. 1993. Intertidal zonation<br />

patterns <strong>of</strong> macro<strong>in</strong>fauna over a range <strong>of</strong> exposed sandy<br />

beaches <strong>in</strong> south central Chile. Mar<strong>in</strong>e Ecology Progress Series 101,<br />

105–118.<br />

Johnson, M. W. 1939 The correlation <strong>of</strong> water movements and<br />

dispersal <strong>of</strong> pelagic larval stages <strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> littoral animals, especially<br />

the sand crab, <strong>Emerita</strong>. Journal <strong>of</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>e Research 11,<br />

236–245.<br />

Johnson, M. W. & Lewis, W. M. 1942 Pelagic larval stages <strong>of</strong> the<br />

sand crabs <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (<strong>Stimpson</strong>) Blepharipoda occidentalis<br />

(Randall), and Lepidopa myops (<strong>Stimpson</strong>). Biological Bullet<strong>in</strong> 83,<br />

67–87.<br />

Knox, C. & Boolotian, R. A. 1963 Functional morphology <strong>of</strong><br />

the external appendages <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong>. Bullet<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Southern California Academy <strong>of</strong> Science 62, 45–68.<br />

MacG<strong>in</strong>itie, G. E. 1938 Movements and mat<strong>in</strong>g habits <strong>of</strong> the sand<br />

crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong>. American Midland Naturalist 19, 471–481.<br />

Nuñez, J., Aracena, O. & López, M. T. 1974 <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> en<br />

Llico, prov<strong>in</strong>cia de Curicó. (Crustacea, Decapoda, <strong>Hippidae</strong>).<br />

Boletín de la Sociedad de Biología Concepción 48, 11–22.<br />

Osorio, C., Bahamonde, N. & López, M. T. 1967 El Limanche<br />

[<strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (<strong>Stimpson</strong>)] en Chile. Boletín Museo Nacional de<br />

Historia Natural 29, 60–116.<br />

Pauly, D. & Gaschütz, G. 1979 A simple method for fitt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

oscillat<strong>in</strong>g length growth data, with a program for pocket calculators.<br />

International Council for the Exploration <strong>of</strong> the Sea Committee<br />

Meet<strong>in</strong>g (Demersal Fish Comm.) 24, 1–26 (mimeo).<br />

Pauly, D., Ingles, J. & Neal, R. 1984 Application to shrimp stocks<br />

<strong>of</strong> objective methods for the estimation <strong>of</strong> growth, mortality and<br />

recruitment related parameters from length–frequency data<br />

(ELEFAN I and II). In Penaeid Shrimps, Their Biology and<br />

Management (Gulland, J. A., Rothschild, B. J., eds) Fish<strong>in</strong>g News<br />

Books, Farnham, Surrey, England, 220–234.<br />

Pauly, D. & Munro, J. L. 1984 Once more on the comparison <strong>of</strong><br />

growth <strong>in</strong> fish and <strong>in</strong>vertebrates. Fishbyte 1, 21.<br />

Penchaszadeh, P. 1971 Observaciones cuantitativas en playas<br />

arenosas de la costa central del Perü con especial referencia a

112 H. Contreras et al.<br />

las poblaciones de Muy-Muy (<strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong>) (Crustacea,<br />

<strong>Anomura</strong>, <strong>Hippidae</strong>). Instituto de Biología Mar<strong>in</strong>a–Ofic<strong>in</strong>a de<br />

Ciencias de la Unesco 6, 1–19.<br />

Perry, D. M. 1980 Factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g aggregation patterns <strong>in</strong> the<br />

sand crab <strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong> (Crustacea, <strong>Hippidae</strong>). Oecologia 45,<br />

379–384.<br />

Sokal, R. R. & Rohlf, F. J. 1969 Biometria, Madrid, H. Blume,<br />

832 pp.<br />

Sparre, P. 1989 What is the optimum <strong>in</strong>terval class size for<br />

length–frequency analysis? Fishbyte 7, 23.<br />

Sparre, P., Urs<strong>in</strong>, E. & Venema, S. C. 1989 Introduction to tropical<br />

fish assessment. Part I. Manual. FAO Fish. Tech. Pap. (306.1).<br />

Rome, FAO, 337 pp.<br />

Vakily, J. M. 1990 Determ<strong>in</strong>ation and comparison <strong>of</strong> growth<br />

<strong>in</strong> bivalves, with emphasis on the tropics and Thailand. Ph.D.<br />

Dissertation, Christian- Albrechts–Universität, Germany,<br />

116 pp+Appendix.<br />

Wenner, A. M. 1972 Sex ratio as a function <strong>of</strong> size <strong>in</strong> the mar<strong>in</strong>e<br />

crustacea. American Naturalist 106, 321–351.<br />

Wenner, A. M. & Haley, S. R. 1981 On the question <strong>of</strong> sex reversal<br />

<strong>in</strong> mole crabs (Crustacea, <strong>Hippidae</strong>). Journal <strong>of</strong> Crustacean<br />

Biology 1, 506–517.<br />

Wenner, A. M., Richard, Y. & Dugan, J. 1987a Hippid crab<br />

population structure and food availability on Pacific shorel<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

Bullet<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>e Science 41, 221–233.<br />

Wenner, A. M., Hubbard, D., Dugan, J., Sh<strong>of</strong>fner, J. & Jellison, K.<br />

1987b Egg production by sand crabs (<strong>Emerita</strong> <strong>analoga</strong>) as a<br />

function <strong>of</strong> size and year class (Decapoda, <strong>Hippidae</strong>). Biological<br />

Bullet<strong>in</strong> 172, 225–235.<br />

Wenner, A. M., Dugan, J. & Hubbard, D. 1993 Sand crab<br />

population biology on the California Islands and ma<strong>in</strong>land. In<br />

Third California Islands Symposium, Recent Advances <strong>in</strong> Research on<br />

California Islands (Hochberg, F. G., ed.). Santa Barbara Museum<br />

<strong>of</strong> Natural <strong>History</strong>, Santa Barbara, CA, 335–348.<br />

Wolff, M. 1989 A proposed method for standarization <strong>of</strong> the<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> class <strong>in</strong>tervals for length frequency analysis. Fishbyte<br />

7, 5.