Language and Cognitive Processes - Institut für Phonetik

Language and Cognitive Processes - Institut für Phonetik

Language and Cognitive Processes - Institut für Phonetik

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

This article was downloaded by:[Universitaetsbibliothek]<br />

[Universitaetsbibliothek]<br />

On: 19 June 2007<br />

Access Details: [subscription number 768609666]<br />

Publisher: Psychology Press<br />

Informa Ltd Registered in Engl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Wales Registered Number: 1072954<br />

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK<br />

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cognitive</strong> <strong>Processes</strong><br />

Publication details, including instructions for authors <strong>and</strong> subscription information:<br />

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713683153<br />

Phonological priming in spoken word recognition with<br />

bisyllabic targets<br />

Elsa Spinelli; Juan Segui; Monique Radeau<br />

To cite this Article: Spinelli, Elsa, Segui, Juan <strong>and</strong> Radeau, Monique , 'Phonological<br />

priming in spoken word recognition with bisyllabic targets', <strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cognitive</strong><br />

<strong>Processes</strong>, 16:4, 367 - 392<br />

To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/01690960042000111<br />

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01690960042000111<br />

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE<br />

Full terms <strong>and</strong> conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-<strong>and</strong>-conditions-of-access.pdf<br />

This article maybe used for research, teaching <strong>and</strong> private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,<br />

re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly<br />

forbidden.<br />

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be<br />

complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae <strong>and</strong> drug doses should be<br />

independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,<br />

dem<strong>and</strong> or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or<br />

arising out of the use of this material.<br />

© Taylor <strong>and</strong> Francis 2007

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

LANGUAGE AND COGNITIVE PROCESSES, 2001, 16 (4), 367–392<br />

Phonological priming in spoken word recognition<br />

with bisyllabic targets<br />

Elsa Spinelli <strong>and</strong> Juan Segui<br />

C.N.R.S. <strong>and</strong> Université René Descartes, Paris, France<br />

Monique Radeau<br />

F.R.N.S., ULB, Brussels, Belgium<br />

Four experiments were carried out to examine phonological priming effects<br />

on bisyllabic target words. In Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 1b, auditorily presented<br />

monosyllabic word <strong>and</strong> pseudoword primes facilitated lexical decisions to<br />

auditorily presented bisyllabic words. This facilitation was found for primes<br />

overlapping the targets’ initial syllable (e.g., ‘‘ver’’ [worm in French] primed<br />

‘‘VERTIGE’’ [VERTIGO]) <strong>and</strong> for primes overlapping the targets’ nal<br />

syllable (e.g., ‘‘tige’’ [stem] primed ‘‘VERTIGE’’). Experiment 2 replicated<br />

the initial-overlap effect for monosyllabic word primes using a crossmodal<br />

(auditory-visual) method; however no facilitation was observed for naloverlap<br />

nor for bisyllabic primes (e.g., ‘‘verger’’ [orchard] did not facilitate<br />

VERTIGE). In Experiment 3, the initial overlap facilitation effect was<br />

replicated in a naming task. These results are interpreted in terms of<br />

activation <strong>and</strong> deactivation of c<strong>and</strong>idates.<br />

An important debate in the eld of spoken word recognition concerns the<br />

processes underlying the mapping of sensory information from the acoustic<br />

input to the stored entries in the lexicon. Central to this debate are the<br />

dynamics of the activation <strong>and</strong> deactivation of lexical units during the<br />

unfolding of the acoustic signal. A useful tool to study these processes is<br />

the phonological priming paradigm. Phonological priming refers to the<br />

Requests for reprints should be addressed to Elsa Spinelli, Max Planck <strong>Institut</strong>e for<br />

Psycholinguistics, Wundtlaan 1, PB 310, 6500 AH Nijmegen, The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

e-mail: elsa.spinelli@mpi.nl<br />

The authors thank Ram Frost, Arthur Samuel <strong>and</strong> one anonymous reviewer for their<br />

helpful comments on this work. We also thank F.X. Alario, D. Dahan <strong>and</strong> D. Swingley for<br />

valuable discussions on this research.<br />

®c 2001 Psychology Press Ltd<br />

http://www.t<strong>and</strong>f.co.uk/journals/pp/01690965.html DOI: 10.1080/01690960042000111

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

368 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

inuence of a prime word on the processing of a subsequently presented<br />

target word that shares a number of phonemes with the prime.<br />

Phonological priming has been used as a measure of activation <strong>and</strong><br />

competition between lexical c<strong>and</strong>idates, <strong>and</strong> the effects obtained with this<br />

paradigm have been used to infer aspects of the dynamics of spoken word<br />

perception. A phonological priming effect suggests that the information<br />

extracted from the prime can activate the representation of the target.<br />

Therefore, we can determine the amount of information that is sufcient to<br />

access the representations of lexical units by varying the amount of overlap<br />

between prime <strong>and</strong> target pairs. Moreover, we can determine which<br />

phonological components (like phonetic features, phonemes or syllables)<br />

are involved in the process of contacting the lexicon, <strong>and</strong> assess the<br />

consequences of a mismatch between the input <strong>and</strong> the form representations<br />

in the processing of spoken words.<br />

Previous studies have found that the conditions under which phonological<br />

priming occurs are different for primes that overlap with the nal<br />

parts of targets (e.g., mean-bean) <strong>and</strong> primes that overlap with the<br />

beginning of targets (e.g., swan-swap) (see Goldinger, 1996; Radeau,<br />

Morais, & Segui, 1995, for reviews). For nal overlap, facilitation is usually<br />

reported for items sharing at least the rime (Emmorey, 1989; Radeau et al.,<br />

1995; Slowiaczek, Nusbaum & Pisoni, 1987; Slowiaczek, Soltano &<br />

McQueen, 1997), but only if both prime <strong>and</strong> target are presented in the<br />

same modality (auditory). Null effects have sometimes been found<br />

(Emmorey, 1989), but to the best of our knowledge, inhibitory effects<br />

have not been reported. The fact that nal-overlap effects occur only<br />

under unimodal (auditory-auditory) conditions, <strong>and</strong> not with crossmodal<br />

presentation, has suggested that such effects do not involve the activation<br />

of the lexical representation of the target (Dumay, Benrass, Barriol, Colin,<br />

Radeau, & Besson, in press; Radeau, Segui & Morais, 1994). The<br />

facilitation effect may be caused by the preactivation of sublexical units.<br />

The fact that rime effects are insensitive to the relative frequency between<br />

primes <strong>and</strong> targets supports the view that these effects do not take place at<br />

a lexical level (Radeau et al., 1994, 1995).<br />

The effects observed for beginning overlap are more complex. The<br />

corresponding hypotheses are directly linked to temporal aspects of the<br />

processing of spoken words. Two distinct effects have generally been<br />

reported, which depend on the degree of phonological overlap. In<br />

monosyllabic items, when only the rst phoneme is shared by primes<br />

<strong>and</strong> targets, facilitatory effects have been reported (Goldinger, Luce,<br />

Pisoni & Marcario, 1992; Slowiaczek & Hamburger, 1992). However, it has<br />

been demonstrated that such effects can be attributed to strategies due to<br />

either the experimental task when the presentation of degraded stimuli<br />

might lead the participants to develop guessing strategies about the missing

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 369<br />

cues (Radeau, Morais & Dewier, 1989; Slowiaczek & Hamburger, 1992),<br />

the proportion of related items or the inclusion of repeated pairs in the<br />

experimental lits (Goldinger et al., 1992; Slowiaczek & Hamburger, 1992).<br />

When two or more of the two rst phonemes are shared, interference<br />

results rather than facilitation (Slowiaczek & Hamburger, 1992). 1 Hamburger<br />

<strong>and</strong> Slowiaczek (1996) found inhibition (relative to the control) in a<br />

condition where strategic involvement was discouraged by the means of a<br />

short inter-stimulus-interval (50 ms) <strong>and</strong> a low proportion of related pairs<br />

(21%). The logic underlying this manipulation was that strategies are more<br />

likely to occur when there is more time separating the primes from the<br />

targets (500 ms) <strong>and</strong> when there is a high proportion of related pairs. The<br />

null effect of these manipulations suggested that the obtained inhibition<br />

was not the consequence of strategic anticipations made by the participants<br />

(but see Goldinger, 1999). Note also that initial-overlap effects are also<br />

found in crossmodal designs (Radeau, 1995; Slowiaczek & Hamburger,<br />

1992). Such effects cannot be attributed to the preactivation of sublexical<br />

units that can be reused for the processing of the target; rather, it seems that<br />

the information from the two sources of sensory input converge in the<br />

amodal lexicon to induce the effect. This argues that initial-overlap effects<br />

result from a competition between lexical units.<br />

Models of spoken word recognition that postulate lateral inhibition (e.g.,<br />

TRACE, McClell<strong>and</strong> & Elman, 1986; ShortList, Norris, 1994) can account<br />

for the beginning overlap inhibition effect. A possible interpretation could<br />

run as follows: During the processing of the prime, the target word is<br />

initially activated as a possible c<strong>and</strong>idate because it shares some sublexical<br />

units (rst phonemes) with the prime. Then, as the prime unfolds <strong>and</strong> the<br />

acoustic information favours the prime over the target, the phonologically<br />

related c<strong>and</strong>idate (the target) is deactivated or inhibited. In a similar way,<br />

during the processing of the target, both c<strong>and</strong>idates are activated, but the<br />

prime benets from preactivation (which is not the case in the non-related<br />

control condition). The competition induced by the preactivation of the<br />

prime in the phonologically related condition is responsible for the<br />

inhibitory effect. Note also that the NAM (Neighbourhood Activation<br />

Model) proposed by Luce (1986), which does not postulate lateral<br />

inhibition, can also account for the beginning overlap inhibition. In<br />

NAM, the probability of identifying a word is calculated as a ratio between<br />

the activation of this word <strong>and</strong> the summed activation of its neighbours<br />

(words of the same length sharing all phonemes but one). A highly<br />

activated neighbour (e.g., a phonologically related prime) decreases the<br />

1 In this study, interference described a case where the three phoneme overlap condition<br />

was slower than the one phoneme condition but did not differ from the control.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

370 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

ratio <strong>and</strong> therefore the probability of identifying the target. A similar<br />

mechanism is postulated in the second version of the cohort model<br />

(Marslen-Wilson, 1987) <strong>and</strong> could account for the results in a similar<br />

fashion.<br />

To sum up, so far, the studies on phonological priming have shown<br />

facilitation effects that reect either strategy (rst phoneme overlap) or the<br />

activation of sublexical units (rime or nal overlap effects), <strong>and</strong> inhibition<br />

effects that reect competition among lexical c<strong>and</strong>idates (when primes <strong>and</strong><br />

targets overlap from the beginning). Note that the explanation of the initial<br />

overlap inhibition depends on the prime containing phonetic information<br />

inconsistent with the target, depressing the target’s activation. The<br />

potential effects of primes that do not mismatch the targets are less clear.<br />

This would be the case if we presented only one portion of the target as<br />

prime (such as the rst syllable of a bisyllabic target), or an embedded<br />

word like ver in French (worm) as a prime for a carrier word like vertige<br />

(vertigo). If we present a syllable that is not a word, we expect facilitation<br />

as Zwitserlood (1989) <strong>and</strong> Marslen-Wilson (1990) observed in crossmodal<br />

priming. If the syllable prime is a word, this facilitation could interact with<br />

lexical competition.<br />

In the present study, we tried to have a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the<br />

nature of beginning <strong>and</strong> nal overlap priming effects. Moreover, we<br />

wanted to assess the consequences of matching <strong>and</strong> mismatching<br />

information on the activation <strong>and</strong> deactivation of lexical c<strong>and</strong>idates. The<br />

aim of Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 1b was to examine phonological priming effects<br />

under a condition of ‘‘partial priming’’ <strong>and</strong> to assess nal <strong>and</strong> initial<br />

overlap effects in the same targets. In Experiment 1a, monosyllabic words<br />

were used as primes (ver-VERTIGE, tige-VERTIGE in French, [worm-<br />

VERTIGO, stem-VERTIGO]). The aim of Experiment 1b was to assess<br />

whether the effects found in Experiment 1a were affected by the lexicality<br />

of the primes. Therefore, pseudowords served as primes (cra-CRAVATE,<br />

vate-CRAVATE [TIE]). The aims of Experiment 2 were to evaluate<br />

whether initial <strong>and</strong> nal overlap effects reect the same level of processing<br />

by using a crossmodal presentation of the items, <strong>and</strong> also to compare<br />

partial (monosyllabic (ver-VERTIGE, tige-VERTIGE) <strong>and</strong> bisyllabic<br />

priming (verger-VERTIGE, prestige-VERTIGE [orchard-VERTIGO,<br />

prestige-VERTIGO]). For beginning overlap, we expected facilitation in<br />

the partial (monosyllabic) priming condition; but in the condition of<br />

bisyllabic priming, the transient activation of the target was predicted to<br />

disappear as the prime is being processed. Experiments 1a, 1b <strong>and</strong> 2 were<br />

run using the lexical decision task. In order to assess the generality of the<br />

effects found in Experiment 2 for partial priming, a fourth experiment was<br />

conducted using the naming task instead of lexical decision, <strong>and</strong><br />

crossmodal presentation of the items as in Experiment 2.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

Method<br />

EXPERIMENT 1A<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 371<br />

Participants. Thirty students of the University René Descartes, Paris<br />

V, participated in the experiment for course credit. All participants were<br />

native speakers of French <strong>and</strong> reported no hearing impairment.<br />

Stimuli <strong>and</strong> design. Thirty-six bisyllabic target words were selected<br />

from a French database, TLF (Trésor de la Langue Française; Imbs, 1971).<br />

Each of these words contained two embedded monosyllabic words as in<br />

‘‘vertige’’ (VERTIGO in French) which contains ‘‘ver’’ (worm) <strong>and</strong> ‘‘tige’’<br />

(stem). Three monosyllabic prime words were chosen for each target. One<br />

corresponded to the rst syllable of the target (e.g., ver-VERTIGE,<br />

beginning-overlap condition); one corresponded to the second syllable of<br />

the target (e.g., tige-VERTIGE, nal-overlap condition) <strong>and</strong> one was not<br />

related to the target phonologically, morphologically, or semantically (e.g.,<br />

brin [str<strong>and</strong>]- VERTIGE, control condition). Stimulus word frequencies<br />

(per million) were as follows: targets, 11; initial-overlap primes, 247; naloverlap<br />

primes, 420; control primes, 189. Stimulus word durations (in<br />

milliseconds) were as follows: targets, 688 ms; initial-overlap primes, 394<br />

ms; nal-overlap primes, 450 ms; control primes, 446 ms. Thirty-six<br />

bisyllabic pseudoword targets were constructed according to the same<br />

criteria as the word targets <strong>and</strong> served as catch trials. Each contained two<br />

embedded monosyllabic words used as primes. Thus, for each subject,<br />

there were 24 related pairs (12 with beginning overlap <strong>and</strong> 12 with nal<br />

overlap) <strong>and</strong> 12 non-related pairs for word targets, <strong>and</strong> 24 related pairs (12<br />

with beginning <strong>and</strong> 12 with nal overlap) <strong>and</strong> 12 non-related pairs for<br />

pseudoword targets. In order to reduce the proportion of related items to<br />

25%, the experimental lists also included 120 bisyllabic ller pairs without<br />

any relation between primes <strong>and</strong> targets, half the targets being words <strong>and</strong><br />

the other half being pseudowords. The experimental words <strong>and</strong> pseudowords<br />

are listed in Appendix A.<br />

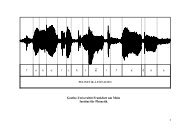

Procedure. All items were recorded in a soundproof room by a female<br />

native speaker of French (rst author) on a digital audio tape (DAT)<br />

recorder. Items were then digitised at a sampling rate of 44 kHz with 16-bit<br />

analog-to-digital conversion using the Audiomedia sound editor on a<br />

Macintosh II FX computer. The items were transferred to the left channel<br />

of the DAT recorder <strong>and</strong> stored as corresponding prime/target pairs with a<br />

50 ms ISI between the prime <strong>and</strong> the target. One second of silence<br />

separated the end of the target from the beginning of the next prime.<br />

Square wave clicks aligned with the onset of the experimental targets were<br />

stored on the right channel of the DAT recorder. The clicks were inaudible

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

372 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

to the participants <strong>and</strong> served to trigger the clock of a 386 PC computer<br />

which recorded the reaction times. Stimuli were counterbalanced across<br />

three experimental lists so that each participant received all conditions<br />

(initial, nal, control) but heard each target only once. The position of the<br />

targets was kept constant across the lists. The order of stimulus<br />

presentation was pseudo-r<strong>and</strong>omised. Participants were informed that<br />

the rst item was always a monosyllabic word <strong>and</strong> the second item could be<br />

either a word or a pseudoword <strong>and</strong> were required to perform a lexical<br />

decision task on the second item by pressing as accurately <strong>and</strong> as quickly as<br />

possible one of two response buttons. They were required to press the<br />

« yes button with the forenger of their preferred h<strong>and</strong>. Response<br />

latencies <strong>and</strong> errors were collected. The duration of the session was<br />

approximately 20 minutes.<br />

Results <strong>and</strong> discussion<br />

Reaction times were calculated from target onset to response onset. Mean<br />

reaction times (RTs) <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard deviations (SD) for word targets in the<br />

three overlap conditions are presented in Table 1. Incorrect responses <strong>and</strong><br />

RTs longer than 1500 ms were removed, excluding 6% of responses. The<br />

results were evaluated using one-way Anovas with 3 levels of condition<br />

(beginning, nal, control). F values are reported by subjects (F 1) <strong>and</strong> by<br />

items (F2) <strong>and</strong> all signicance tests have associated p levels of less than .05.<br />

Analyses of RTs revealed a main effect of overlap condition, signicant<br />

by subjects, (F 1(2, 58) ˆ 26.15, p < .001), <strong>and</strong> by items (F 2(2, 70) ˆ 10.73,<br />

p < .001). Planned comparisons yielded a signicant facilitatory effect of<br />

the beginning overlap condition (F 1(1, 29) ˆ 19.9, p < .001, F 2(1, 35) ˆ<br />

TABLE 1<br />

Mean reaction times in milliseconds (ms), st<strong>and</strong>ard deviation for correct<br />

responses to the word targets <strong>and</strong> percentage of errors in the three<br />

overlap conditions of Experiment 1a (word primes) <strong>and</strong> Experiment 1b<br />

(pseudoword primes), with auditory-auditory presentation<br />

Beginning Final Control<br />

Beginning<br />

priming<br />

Final<br />

priming<br />

Exp 1a<br />

RT (ms) 826 801 866 ‡ 40 ‡ 65<br />

SD (81) (74) (83)<br />

Errors (%) 6 6 7<br />

Exp 1b<br />

RT (ms) 776 741 816 ‡ 40 ‡ 75<br />

SD (65) (67) (59)<br />

Errors (%) 2 2 3

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 373<br />

6.46, p < .01), as well as a facilitatory effect of the nal overlap condition<br />

(F 1(1, 29) ˆ 47.47, p < .001, F 2(1, 35) ˆ 20.27, p < .001). Analyses<br />

conducted on errors revealed no effect of overlap condition (F 1(2, 58 < 1;<br />

F 2 (2, 70) < 1).<br />

The partial priming results showed that the auditory presentation of a<br />

prime (e.g., ‘‘ver’’) facilitates the subsequent processing of a target word<br />

that begins with the same phonemes (e.g., ‘‘vertige’’), compared to an<br />

unrelated prime (e.g., ‘‘brin’’). Moreover, the auditory presentation of the<br />

end of this word (e.g., ‘‘tige’’), also facilitates its subsequent processing.<br />

Note that because the primes used in this experiment were not only<br />

fragments of the targets but also words, the question remains of whether<br />

the lexicality of the primes inuenced the priming effects obtained. To<br />

answer this question, pseudoword primes were used in Experiment 1b.<br />

Method<br />

EXPERIMENT 1B<br />

Participants. Thirty students of the University René Descartes, Paris<br />

V, participated in this experiment. They were selected in the same way as<br />

in Experiment 1a but were paid for their participation.<br />

Stimuli <strong>and</strong> design. We selected 36 bisyllabic target words from a<br />

French database, TLF (Trésor de la Langue Française; Imbs, 1971).<br />

Contrary to Experiment 1a, neither syllable of these bisyllabic words<br />

matched an existing word (i.e. they were composed of two pseudowords,<br />

e.g., CRAVATE [TIE]). As in Experiment 1a, each bisyllabic target was<br />

associated to three monosyllabic primes. One prime corresponded to the<br />

rst syllable of the target (e.g., cra-CRAVATE); another matched the<br />

second syllable of the target (e.g., vate-CRAVATE) <strong>and</strong> a third served as<br />

control prime (e.g., dule-CRAVATE). The targets’ average frequency is<br />

25 occurrences per million (frequencies given by TLF). Stimulus word<br />

durations (in milliseconds) were as follows: targets, 678 ms; initial-overlap<br />

primes, 345 ms; nal-overlap primes, 523 ms; control primes, 435 ms.<br />

Thirty-six bisyllabic pseudoword targets were constructed according to the<br />

same criteria as the word targets <strong>and</strong> served as catch trials. Each contained<br />

two embedded monosyllabic pseudowords used as primes. The experimental<br />

lists also included 120 bisyllabic ller pairs without any relation<br />

between primes <strong>and</strong> targets, half the targets being words <strong>and</strong> the other half<br />

being pseudowords. Therefore, the proportion of related pairs is 25%. The<br />

experimental words <strong>and</strong> pseudowords are listed in Appendix B. The<br />

procedure was the same as in Experiment 1a.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

374 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

Results<br />

The results were analysed in the same way as in the rst experiment. The<br />

percentage of rejected values was 4%.<br />

As shown in the right-most column of Table 1, both overlap conditions<br />

still gave rise to facilitation. The effect of overlap condition was signicant<br />

by subjects (F1(2, 58) ˆ 30.9, p < .001), <strong>and</strong> by items (F2(2, 70) ˆ 31.4, p <<br />

.001). The facilitatory effect was signicant in the beginning overlap<br />

condition (F 1(1, 29) ˆ 18.9, p < .001, F 2(1, 35) ˆ 18.2, p < .001), <strong>and</strong> in the<br />

nal overlap condition (F 1(1, 29) ˆ 51.5, p < .001, F 2(1, 35) ˆ 62.4, p <<br />

.001). Analyses conducted on errors revealed no effect of overlap<br />

condition (F 1(2, 58 < 1; F 2(2, 70) < 1).<br />

Discussion<br />

The results of this experiment showed exactly the same pattern as those of<br />

Experiment 1a. For the beginning overlap condition, we obtained the same<br />

facilitation effect (40 ms) with pseudoword primes <strong>and</strong> with word primes.<br />

For the nal overlap condition, we obtained a 75 ms facilitation effect with<br />

pseudoword primes compared to a 65 ms effect with word primes.<br />

Therefore, it seems that the lexicality of the prime did not inuence the<br />

effects obtained with partial priming. Note that comparable results were<br />

obtained by Slowiaczek <strong>and</strong> Hamburger (1992) <strong>and</strong> Radeau et al. (1994)<br />

for nal overlap. With monosyllabic primes <strong>and</strong> targets, they showed that<br />

the nal facilitation effect was not affected by the lexical status of the<br />

primes.<br />

By means of this partial priming design in which we presented a<br />

fragment of the target as a prime, we obtained a facilitatory effect for<br />

initial overlap, whereas inhibitory effects have generally been reported for<br />

such an overlap. We also obtained a facilitatory effect for nal overlap,<br />

which is consistent with the data reported in the literature. What is the<br />

nature of the processes underlying the initial <strong>and</strong> nal facilitation effects?<br />

One possibility is that during the processing of the target, the sublexical<br />

units activated by the prime are reused to speed up the processing of the<br />

target, leading to shorter response times in the initial <strong>and</strong> nal conditions<br />

compared to the control condition. Another possibility is that the lexical<br />

representation of the target is activated by the information carried by the<br />

prime. Recall that the prime does not provide mismatching information,<br />

unlike previous studies that involved monosyllabic words. 2 Thus ver <strong>and</strong><br />

cra may activate the representations of vertige <strong>and</strong> cravate <strong>and</strong> so may tige<br />

2 It could be argued that the silence occurring after the prime can be taken as a cue for<br />

word offset thus inducing, in the same way as a mismatching phoneme, the deactivation of the<br />

target. This point will be discussed in the general discussion.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 375<br />

<strong>and</strong> vate, leading to shorter response times for vertige <strong>and</strong> cravate, whose<br />

representations have been preactivated. A third possibility is that initial<br />

<strong>and</strong> nal facilitation effects reect different levels of processing.<br />

In order to examine this point, primes <strong>and</strong> targets were presented in<br />

different modalities in the following experiment. If the preactivation of<br />

sublexical units is the only origin of the facilitation observed for initial <strong>and</strong><br />

nal overlap, no facilitation should be found using a crossmodal paradigm,<br />

because the sublexical units activated by the prime could not be reused to<br />

speed up the processing of the target in this case. On the contrary, if initial<br />

<strong>and</strong> nal facilitations reect the activation of the lexical representation of<br />

the target, they should be modality independent <strong>and</strong> should remain when<br />

tested in different modalities.<br />

As the data reviewed in the introduction suggest, beginning overlap<br />

effects reect lexical competition. Therefore we hypothesise that in the<br />

partial priming condition of Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 1b, with the rst syllable<br />

of the target presented as prime, the facilitation reects the activation of<br />

the lexical representation of the target, <strong>and</strong> not only the use of<br />

preactivated sublexical units. If this hypothesis is true, we predict that<br />

the initial overlap effect will be observed with a crossmodal paradigm. On<br />

the contrary, the nal facilitation effect has been interpreted as the result<br />

of activation of sublexical units by the prime. Therefore, we predict that<br />

the effect will disappear in the crossmodal paradigm.<br />

To further ascertain the nature of the beginning overlap effect, we<br />

compared the partial priming condition with a condition of bisyllabic<br />

priming in which bisyllabic words sharing the rst syllable with the target<br />

served as primes (verger-VERTIGE, [orchard-VERTIGO]. This bisyllabic<br />

priming condition parallels the beginning overlap that is generally used in<br />

phonological priming experiments with monosyllables since the activation<br />

of a given c<strong>and</strong>idate is measured after the processing of mismatching<br />

information. 3<br />

Note nally that we aimed to compare bisyllabic word primes <strong>and</strong><br />

monosyllabic primes. Because the lexicality of the prime did not inuence<br />

our previous effects, only word primes were used in the following<br />

experiments.<br />

Method<br />

EXPERIMENT 2<br />

Participants. Sixty students participated in this experiment for course<br />

credit. All participants were native speakers of French, had normal or<br />

3 Final overlap bisyllabic primes were used in the crossmodal experiment to parallel the<br />

experimental conditions of the partial priming. A null effect is predicted in this condition for<br />

the same reason as for the nal partial priming.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

376 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

corrected vision <strong>and</strong> reported no hearing impairment. Half of them were<br />

tested in the partial priming condition, <strong>and</strong> the other half in the bisyllabic<br />

priming condition.<br />

Stimuli <strong>and</strong> design. For the partial priming condition, the primes were<br />

re-recorded tokens of the primes used in Experiment 1a. The average<br />

duration of the primes was 343 ms for the initial-overlap set, 369 ms for the<br />

nal-overlap set <strong>and</strong> 395 ms for the control condition.<br />

For the bisyllabic priming condition, the 36 bisyllabic word targets of<br />

Experiment 1a also served as targets. Three bisyllabic prime words were<br />

chosen for each target. One began with the rst syllable of the target (e.g.,<br />

verger-VERTIGE, [orchard- VERTIGO], beginning-overlap condition);<br />

one ended with the second syllable of the target (e.g., prestige-VERTIGE,<br />

nal-overlap condition) <strong>and</strong> one was not related to the target (e.g.,<br />

tambour [drum]- VERTIGE, control condition). Stimulus word frequencies<br />

(per million) were as follows: initial-overlap primes, 8; nal-overlap<br />

primes, 8; control primes, 7. Stimulus word durations (in milliseconds)<br />

were as follows: initial-overlap primes, 575 ms; nal-overlap primes, 613<br />

ms; control primes, 611 ms. Thirty-six bisyllabic pseudowords containing<br />

two embedded words served as catch trials. As ller targets, 120 bisyllabic<br />

items (60 words <strong>and</strong> 60 pseudowords) were included in the experimental<br />

lists. One hundred <strong>and</strong> twenty bisyllabic words unrelated to the targets<br />

served as ller primes. The proportion of related items was 25%. The<br />

experimental words <strong>and</strong> pseudowords are listed in Appendix C.<br />

Procedure. The prime words were recorded in a soundproof room by a<br />

female native speaker of French. The stimuli were sampled at 44 kHz <strong>and</strong><br />

then transferred in a computer at a sampling rate of 22.05 kHz <strong>and</strong> 16 bit<br />

conversion using the Wave Studio sound editor. Participants were tested<br />

individually in a quiet room. The prime was presented auditorily at a<br />

comfortable sound level through Sony MDR-P1 headphones. At the end<br />

of the auditory prime <strong>and</strong> after a delay of 50 ms (ISI), the target was<br />

visually displayed in upper case at the centre of the computer screen <strong>and</strong><br />

remained on the screen until the participant’s response. The participants<br />

were informed that the visual target could be either a word or a<br />

pseudoword <strong>and</strong> were asked to perform a lexical decision task on the visual<br />

target. The computer clock was triggered by the presentation of the target<br />

on the screen <strong>and</strong> stopped by the response. Each participant was tested<br />

either in the partial or in the bisyllabic priming condition.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

Results<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 377<br />

The results are presented in Table 2. Incorrect responses <strong>and</strong> RTs longer<br />

than 1500 ms were removed, excluding 4% of responses. One item that<br />

gave rise to extremely long reaction times in the control trials of the<br />

bisyllabic condition was also discarded from the analyses. Two-way<br />

analyses of variance with overlap condition (beginning, nal, control)<br />

<strong>and</strong> priming condition (partial, bisyllabic) were performed on the data.<br />

Analyses of variance conducted on RTs revealed no main effect of<br />

overlap condition (F 1(2, 116) ˆ 2.64; p < .07; F 2(2, 69) ˆ 1.75, p < .18).<br />

However, the overlap £ priming condition interaction was signicant by<br />

subjects (F 1(2, 116) ˆ 6.11; p < .003) <strong>and</strong> by items (F 2(2, 69) ˆ 3.9, p <<br />

.02). Planned comparisons were conducted to assess the effect of the<br />

different overlap conditions under the partial <strong>and</strong> bisyllabic priming<br />

conditions. In the partial priming condition, a signicant facilitatory effect<br />

of the beginning overlap condition relative to the control condition was<br />

obtained (F 1(1, 29) ˆ 14.16; p < .001; F 2(1, 35) ˆ 5.36; p < .025). For nal<br />

overlap, there was not a signicant difference between the related <strong>and</strong> the<br />

control conditions (both F 1 <strong>and</strong> F 2 < 1). In the bisyllabic priming condition,<br />

planned comparisons showed no effect of either type of overlap relative to<br />

the control condition (beginning overlap: F 1(1, 29) ˆ 1.69, p < .20; F 2(1,<br />

34) ˆ 1.67, p < .20); nal overlap: F 1(1, 29) ˆ 1.93, p < .17; F 2(1, 34) ˆ<br />

1.04, p < .32).<br />

Analyses conducted on errors revealed no main effect of overlap<br />

condition (both F 1 <strong>and</strong> F 2 < 1) <strong>and</strong> no interaction between overlap <strong>and</strong><br />

priming conditions (F 1 close to 1 <strong>and</strong> F 2 < 1).<br />

TABLE 2<br />

Mean reaction times in milliseconds (ms), st<strong>and</strong>ard deviation for correct<br />

responses to the word targets <strong>and</strong> error rates in the three overlap<br />

conditions of Experiment 2 with auditory-visual presentation<br />

Beginning Final Control<br />

Beginning<br />

priming<br />

Final<br />

priming<br />

Partial priming<br />

RT (ms) 588 621 619 ‡ 31 ¡ 2<br />

SD (82) (101) (90)<br />

Errors (%) 3 3 3<br />

Bisyllabic priming<br />

RT (ms) 621 619 607 ¡ 14 ¡ 12<br />

SD (79) (77) (71)<br />

Errors (%) 3 2 4

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

378 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

Discussion<br />

For partial priming, facilitation was found only for prime words<br />

overlapping with targets in the initial syllable; no priming was observed<br />

for primes overlapping in the second syllable. The fact that the initial<br />

facilitation effect remains when the target is visually presented supports<br />

the idea that the lexical representation of the target is activated during the<br />

processing of the prime. Indeed, if we suppose that the 50 ms interstimulus-interval<br />

between the end of the prime <strong>and</strong> the presentation of the<br />

target is not long enough to be processed as mismatching information, the<br />

target occurs while it is still activated by the prime. This preactivation of<br />

the lexical representation of the target would then be responsible for the<br />

initial-overlap facilitation effect.<br />

For nal overlap, the lack of facilitation is compatible with previous<br />

results in the literature, as nal phonological overlap effects have never<br />

been reported with a crossmodal paradigm. These results thus argue in<br />

favour of the idea that the processes responsible for the nal overlap<br />

facilitation involve only the activation of sublexical units. The nal<br />

facilitation obtained in auditory-auditory priming could be due to the fact<br />

that primes <strong>and</strong> targets share a number of sublexical units. This means that<br />

although hearing tige would facilitate the subsequent processing of vertige,<br />

it would not activate its lexical representation.<br />

In the condition of bisyllabic priming, the beginning overlap condition<br />

did not give rise to any facilitation of target processing. Hence, depending<br />

on the nature of the prime (monosyllabic as in ‘‘ver-vertige’’ or bisyllabic<br />

as in ‘‘verger-vertige’’), we observed either facilitation or no effect,<br />

respectively. Moreover, although not signicant, the results with bisyllabic<br />

primes suggest inhibition rather than facilitation. According to our<br />

interpretation, when the prime was a monosyllabic word, the target<br />

received bottom up activation from the prime <strong>and</strong> remained activated<br />

because there was no mismatching information in the acoustic realisation<br />

of the prime. Thus, the representation of the preactivated target was not<br />

deactivated when the target was presented. On the contrary, when the<br />

prime was a bisyllabic word, it induced deactivation of the target. In the<br />

case of ‘‘verger-VERTIGE’’, hearing the beginning of the prime would<br />

send bottom up activation to a cohort of c<strong>and</strong>idates beginning by ‘‘ver’’,<br />

but during the processing of ‘‘g’’ in ‘‘verger’’, the word ‘‘vertige’’ would<br />

start to be deactivated or inhibited. Thus, at the end of the prime ‘‘verger’’,<br />

the word ‘‘vertige’’ would no longer be activated when subsequently<br />

presented as a target.<br />

Our results are compatible with those reported by Zwitserlood (1989)<br />

who found that the two semantically related targets ‘‘geld’’ (money in<br />

Dutch) <strong>and</strong> ‘‘boot’’ (ship) were facilitated when presented during the /t/ of

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 379<br />

the auditorily presented primes ‘‘kapitaal’’ (capital) <strong>and</strong> ‘‘kapitein’’<br />

(captain). However, when the visual target appeared at the end of the<br />

prime, only the appropriate related target was facilitated. This showed<br />

that, although both c<strong>and</strong>idates had been activated in a rst stage,<br />

facilitation disappeared as soon as the sensory information favoured one<br />

of the c<strong>and</strong>idates over the others.<br />

In Experiments 1a, 1b <strong>and</strong> 2, we used a lexical decision task. It could be<br />

argued that a checking mechanism for congruency between prime <strong>and</strong><br />

target would be involved in our effects (Balota & Chumbley, 1984). Such a<br />

mechanism would be described as the tendency of the subjects to respond<br />

« yes when the pairs are phonologically related <strong>and</strong> « no when the<br />

pairs are not related. This would then lead to a decrease in response times<br />

for the related pairs of words (since the result of checking for relatedness is<br />

compatible with the word responses) <strong>and</strong> to an increase in response times<br />

for the control pairs of words (since the result is not compatible with the<br />

‘‘yes’’ responses in that case). Let us note that if this kind of checking<br />

mechanism was involved, it should produce a facilitation effect for both<br />

kinds of overlap <strong>and</strong> not only for beginning overlap. However, to conrm<br />

that the beginning overlap facilitation effect did result from activation by<br />

the prime of the representation of the target, in Experiment 3, the partial<br />

priming conditions of Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 2 were re-examined with a<br />

naming task.<br />

Method<br />

EXPERIMENT 3<br />

Participants. Thirty students participated in this experiment for course<br />

credit. They were selected according to the same criteria as in Experiment<br />

2.<br />

Stimuli <strong>and</strong> design. The items were the same as those of Experiment 1a<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2 (partial priming). However, pseudowords were not included in this<br />

experiment.<br />

Procedure. The stimuli were presented as in Experiment 2. Instead of<br />

performing a lexical decision task on the targets, the participants were<br />

asked to pronounce each word as rapidly <strong>and</strong> as accurately as possible. The<br />

vocal response triggered a voice key connected to the computer. The target<br />

remained on the screen until a vocal response was made. Naming latencies<br />

were measured from target onset to the triggering of the voice key by the<br />

participant’s response. Occasional naming errors were collected on-line by<br />

the experimenter.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

380 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

Results<br />

Mean correct RTs <strong>and</strong> SDs for the targets in the different overlap<br />

conditions are given in Table 3. Mean RTs were analysed by subjects <strong>and</strong><br />

by items with overlap conditions as main factor. The percentage of rejected<br />

values was 4%.<br />

One-way Anovas conducted on RTs revealed a main effect of overlap<br />

condition, signicant by subjects (F 1(2, 58) ˆ 7.08, p < .002), but<br />

marginally signicant by items (F 2(2, 70) ˆ 2.76, p < .068). Planned<br />

comparisons yielded a signicant facilitatory effect of beginning overlap<br />

(F 1(1, 29) ˆ 13.26, p < .001, F 2(1, 35) ˆ 4.36, p < .04) but no signicant<br />

effect of nal overlap (F 1(1, 29) ˆ 2.96, p < .92, F 2(1, 35) < 1). Analyses<br />

conducted on errors revealed no main effect of overlap (F 1(2, 58) close to 1<br />

<strong>and</strong> F 2(2, 70) < 1).<br />

Discussion<br />

Experiment 3 was designed to provide evidence that the facilitation effect<br />

observed in the previous experiments with initial overlap did not take<br />

place at a decisional level. For that purpose, we used a naming task instead<br />

of a lexical decision task. When the subjects had to name the targets, we<br />

observed the same pattern of results found with the lexical decision task,<br />

i.e., a facilitation for beginning overlap <strong>and</strong> no effect for nal overlap. In<br />

this task, participants do not make any binary decisions since only words<br />

are presented. Thus, because we replicate the beginning overlap<br />

facilitation effect, this effect cannot be attributed to an artifact of the<br />

lexical decision task. On the contrary, we interpret the beginning overlap<br />

facilitation effect in terms of the activation of the representations of lexical<br />

c<strong>and</strong>idates.<br />

GENERAL DISCUSSION<br />

The aim of the present research was to examine the processes of activation<br />

<strong>and</strong> deactivation of c<strong>and</strong>idates during spoken word processing. This<br />

TABLE 3<br />

Mean naming latencies in milliseconds (ms), st<strong>and</strong>ard deviation for correct responses<br />

to the targets <strong>and</strong> error rates in the three priming conditions of Experiment 3 with<br />

auditory-visual presentation<br />

Beginning Final Control<br />

Beginning<br />

priming<br />

Final<br />

priming<br />

RT (ms) 487 497 506 ‡ 19 ‡ 9<br />

SD (62) (59) (65)<br />

Errors (%) 3 2 2

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 381<br />

question was examined using the phonological priming paradigm with<br />

bisyllabic words. We found that partial priming (i.e., when the prime is the<br />

rst or the second syllable of the target) facilitates target processing when<br />

the prime/target pairs are presented in the auditory modality (Experiment<br />

1a <strong>and</strong> 1b). On the basis of the results of Experiments 2 <strong>and</strong> 3, we<br />

suggested that nal overlap facilitation was prelexical, whereas initial<br />

overlap facilitation reected the activation of c<strong>and</strong>idates at a lexical level<br />

of processing.<br />

Interpretation of the partial priming results<br />

In the interpretation of the results, we have made a distinction between the<br />

effects observed in the nal <strong>and</strong> beginning overlap conditions. For partial<br />

priming, we found a nal-overlap facilitation effect for word <strong>and</strong><br />

pseudoword primes in the auditory-auditory modality. The nal-overlap<br />

facilitation disappeared when primes <strong>and</strong> targets were presented in two<br />

different modalities. Taken together, the results suggest that the nal<br />

overlap facilitation effect is prelexical. By prelexical, we mean that the<br />

processing of the prime does not involve the activation of the lexical<br />

representation of the target. The facilitation effect does not arise from the<br />

preactivation of the representation of the target but from the preactivation<br />

of the sublexical units (e.g., phonemes) shared by the prime <strong>and</strong> the target.<br />

If the sublexical units preactivated during the processing of the prime are<br />

not reheard, as it is the case in the crossmodal condition, the nal overlap<br />

facilitation is not observed.<br />

In the initial-overlap partial priming condition (e.g., ver-VERTIGE), we<br />

also found facilitation but we suggest that the processing underlying the<br />

beginning overlap facilitation effect is different from that at the basis of the<br />

nal facilitation effect. We found this effect with both word <strong>and</strong><br />

pseudoword primes in the auditory-auditory modality condition. Moreover<br />

the effect remained when tested in the crossmodal condition. For that<br />

reason, we suggest that the beginning overlap facilitation effect occurs at<br />

the lexical level. By lexical, we mean that the processing of the prime<br />

induces the activation of the lexical representation of the target. The<br />

facilitation effect results from the fact that the lexical representation of the<br />

target (e.g., VERTIGE) has been preactivated during the processing of the<br />

prime (e.g., ver) <strong>and</strong> has not been deactivated at the time of target<br />

presentation. This is not the case in the control (unrelated) condition in<br />

which the lexical representation of the target has not been preactivated at<br />

all. The facilitation effect is based on the fact that the representation of the<br />

target remains activated after the end of prime presentation. This implies<br />

that the system does not take the silence occurring at the end of the prime<br />

(ISI) as mismatching information regarding the form representation of the

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

382 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

target. Indeed, we assume that the silence in this case is short enough not<br />

to be taken as a word boundary <strong>and</strong> therefore as mismatching information.<br />

A suggestive comparison could be made with the silences (closure<br />

durations) that are characteristic of stop consonants. In normal speech,<br />

the closure duration of voiceless stop consonants is usually a bit longer<br />

than 50 ms (Crystal & House, 1988) <strong>and</strong> this suggests that our short silence<br />

could not be taken as a cue for a word boundary.<br />

Another point that should be considered is the activation of the lexical<br />

representation of the prime word which becomes activated <strong>and</strong> competes<br />

with the target for recognition. This representation can be activated not<br />

only during the processing of the prime but also during the processing of<br />

the target (as in Experiments 1a, 2 <strong>and</strong> 3 where the targets were formed of<br />

two embedded words). Previous studies have suggested that during the<br />

processing of such carrier words, the embedded words are activated under<br />

some conditions. Although it seems clear that the initial embedded words<br />

become activated during the processing of the carrier word (Prather &<br />

Swinney, 1977; see also Frauenfelder & Peeters, 1990), the results are not<br />

as clear for the nal embedded words. Evidence for the activation of the<br />

second embedded word in bisyllabic carrier words has sometimes been<br />

found (Luce & Cluff, 1998; Shillcock, 1990; Vroomen & De Gelder, 1997)<br />

but not in all experiments (Gow & Gordon, 1995; Prather & Swinney,<br />

1977; see also Frauenfelder & Peeters, 1990).<br />

In principle, if embedded words become activated during the processing<br />

of the carrier word, they should compete with the carrier word for<br />

recognition <strong>and</strong> then lower the activation of the carrier word. 4 However, in<br />

Experiments 1a (where the targets were carrier words composed of two<br />

embedded words) <strong>and</strong> 1b (where the targets were composed of two<br />

pseudowords), we obtained exactly the same pattern of results. This means<br />

that when the prime is a word, the fact that its representation becomes<br />

activated does not inuence the facilitation effect.<br />

This result could be accounted for in several ways. A rst possibility is<br />

that, as is postulated in the early version of the Cohort model (Marslen-<br />

Wilson & Welsh, 1978), there is no lateral inhibition between lexical nodes<br />

<strong>and</strong> therefore, words do not compete directly with each other. In this case,<br />

the activation of ver <strong>and</strong> other members of the cohort does not have a<br />

direct inuence on the activation of the target vertige. Another possibility<br />

is that there is direct competition between c<strong>and</strong>idates, via lateral inhibition<br />

(as postulated in the models TRACE <strong>and</strong> Shortlist). As in the cohort case,<br />

the prime word ver becomes activated, as well as other c<strong>and</strong>idates such as<br />

verve, vertu, verveine . . . . On this account, the target receives inhibition<br />

4 Surprisingly, Luce <strong>and</strong> Lyons (1999) showed that bisyllabic words containing an initial<br />

embedded word were processed faster than bisyllabic words composed of two pseudowords.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 383<br />

from the prime, <strong>and</strong> also from all of the other lexical c<strong>and</strong>idates activated<br />

by the prime. This explain how inhibition of the target may arise from a<br />

non-word prime: the inhibition comes from actual words activated by the<br />

prime. For example, although the prime cra which is not a word does not<br />

compete directly with the target, it activates a number of other competitors<br />

beginning with cra (like crane, crabe, cratère . . . .) which themselves<br />

compete with the target. Because the target has to compete with all the<br />

members of the cohort activated by the prime, the effect of an additional<br />

competitor (i.e., the prime itself) is probably too weak to manifest itself in<br />

the beginning overlap facilitation effect of Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 1b. This<br />

argument is also valid for Cohort II <strong>and</strong> for NAM in which word<br />

identication is computed as a ratio, <strong>and</strong> where having one more c<strong>and</strong>idate<br />

in the denominator of the ratio should not play any role. The important<br />

point is that as there must be many c<strong>and</strong>idates activated by the prime<br />

anyway, there is no effect of having one more c<strong>and</strong>idate activated,<br />

whatever the nature of the competition process.<br />

Interpretation of the bisyllabic priming results<br />

We now turn to the results for initial overlap <strong>and</strong> bisyllabic priming.<br />

Contrary to the initial partial priming, which facilitated processing of the<br />

target, the same target primed with a bisyllabic word beginning with the<br />

rst same syllable was not facilitated. Although not signicant, the results<br />

suggested inhibition rather than facilitation. This result is compatible with<br />

previous crossmodal priming results (e.g., Marslen-Wilson, 1990). Marslen-<br />

Wilson found that (e.g.) ‘‘dock’’ facilitated ‘‘DOG’’ when the target was<br />

presented 50 ms before the end of the vowel in ‘‘dock’’; however, ‘‘dock’’<br />

inhibited ‘‘DOG’’ when the target was presented at the offset of the prime.<br />

This change in the effect of the prime under different stimulus onset<br />

asynchrony reects multiple activation <strong>and</strong> selection of c<strong>and</strong>idates.<br />

The results of Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 1b suggest that during the processing<br />

of the initial segments of a bisyllabic prime like verger, the lexical<br />

representation of the target vertige is initially activated. However, at the<br />

end of the prime verger, vertige is no longer activated. It seems then that<br />

the mismatching information contained in the prime allowed the<br />

deactivation of the target. Note that our results cannot tease apart<br />

whether the deactivation is due to lateral competition or simply to<br />

mismatch with the input.<br />

Consider the models that postulate lateral inhibition between word<br />

nodes (TRACE, Shortlist). If the mismatching c<strong>and</strong>idates have been<br />

actively inhibited by the winner <strong>and</strong> if one of these inhibited c<strong>and</strong>idates<br />

was subsequently presented as a target, its processing should be slowed<br />

down compared to a control condition. Rather than lack of facilitation in

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

384 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

bisyllabic priming condition of Experiment 2, we would then expect an<br />

inhibitory effect of such prime/target relationship.<br />

Although there was a tendency for inhibition in the bisyllabic priming<br />

condition of Experiment 2, the effect failed to reach signicance. As<br />

primes <strong>and</strong> targets were matched in frequency, the relative frequency<br />

between primes <strong>and</strong> targets which has sometimes been shown to have an<br />

effect in priming experiments (Luce, Pisoni & Goldinger, 1990; Marslen-<br />

Wilson, 1990) is here a factor that cannot account for this lack of<br />

inhibition. However, it is possible that the overlap between the primes <strong>and</strong><br />

targets was not sufcient to induce inhibition. Previous experiments using<br />

monosyllabic words report beginning overlap inhibitory effect with an<br />

overlap of at least 66.6% (2 phonemes out of 3; Marslen-Wilson, 1990) up<br />

to 75% (3 phonemes out of 4; Hamburger & Slowiaczek, 1996) whereas the<br />

overlap we used was not greater than 3 phonemes out of 6 or 7 (50% or<br />

43%). Moreover, inhibitory effects were also found with multisyllabic<br />

prime/target pairs by Monsell & Hirsh (1998, Exp 3a, 3b <strong>and</strong> 4). With a<br />

continuous lexical decision paradigm with long lags of priming (1.2 to 4<br />

minutes in average), Monsell <strong>and</strong> Hirsh obtained increased response times<br />

for words preceded by words sharing the rst syllable. However, many of<br />

the prime/target pairs shared more than the initial syllable (e.g., kidneykidnap,<br />

cinema-cinnamon). The average phonemic overlap was thus 66%<br />

in their experiments (3.7 out of 5.6 phonemes) which led us to suppose that<br />

the failure to nd an inhibitory effect in our Experiment 2 might have been<br />

related to the small amount of phonemic overlap.<br />

In summary, the results of this study show that initial <strong>and</strong> nal overlap<br />

priming effects reect different levels of processing. Although the<br />

information carried by the beginning of words is sufcient to activate<br />

their representation, processing the end of a word does not seem to<br />

activate its representation. Moreover, when the signal carries mismatching<br />

information, the lexical representations of the mismatching c<strong>and</strong>idates are<br />

deactivated or inhibited. These results thus provide evidence for successive<br />

stages of activation <strong>and</strong> deactivation of lexical c<strong>and</strong>idates according to<br />

their degree of matching with the unfolding input.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Manuscript received September 1999<br />

Revised manuscript received June 2000<br />

Balota, D.A., & Chumbley, J.I. (1984). Are lexical decisions a good measure of lexical access?<br />

The role of word frequency in the neglected decision stage. Journal of Experimental<br />

Psychology: Human Perception <strong>and</strong> Performance, 10, 340–357.<br />

Burton, M.W. (1992, November). Syllable priming in auditory word recognition. Poster session<br />

presented at the 33rd annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, St. Louis, MO.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 385<br />

Crystal, T.H., & House, A.S. (1988). Segmental durations in connected speech signals: current<br />

results. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 83 (4), 1553–1573.<br />

Dumay, N., Benrass, A., Barriol, B., Colin, C., Radeau, M., & Besson, M. (in press).<br />

Behavioral <strong>and</strong> electrophysiological study of phonological priming between bisyllabic<br />

spoken words. Journal of <strong>Cognitive</strong> Neuroscience.<br />

Emmorey, K.D. (1989). Auditory morphological priming in the lexicon. <strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Cognitive</strong> <strong>Processes</strong>, 4, 73–92.<br />

Frauenfelder, U.H., & Peeters, G. (1990). Lexical segmentation in TRACE: An exercise in<br />

simulation. In G.T.M Altmann (Ed.), <strong>Cognitive</strong> models of speech processing, pp. 50–86.<br />

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.<br />

Goldinger, S.D. (1996). Auditory lexical decision. <strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cognitive</strong> <strong>Processes</strong>, 11, 559–<br />

567.<br />

Goldinger, S.D. (1999). Only the shadower knows : Comment on Hamburger & Slowiaczek<br />

(1996). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 6, 347–351.<br />

Goldinger, S.D., Luce, P.A., & Pisoni, D.B. (1989). Priming lexical neighbors of spoken<br />

words: Effects of competition <strong>and</strong> inhibition. Journal of Memory <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong>, 28, 501–<br />

518.<br />

Goldinger, S.D., Luce, P.A., Pisoni, D.B. & Marcario, J.K. (1992) Form-based priming in<br />

spoken word recognition: the roles of competition <strong>and</strong> bias. Journal of Experimental<br />

Psychology: Learning, Memory, <strong>and</strong> Cognition, 18, 1211–1238.<br />

Gow, D.W. Jr., & Gordon, P.C. (1995). Lexical <strong>and</strong> prelexical inuences on word<br />

segmentation: Evidence from priming. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human,<br />

Perception <strong>and</strong> Performance, 21, 344–359.<br />

Hamburger, M.B., & Slowiaczek, L.M. (1996). Phonological priming reects lexical<br />

competition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 520–525.<br />

Imbs, P. (1971). Trésor de la langue Française. Dictionnaire des Fréquences (French <strong>Language</strong><br />

Frequency counts). Paris: Klincksieck.<br />

Luce, P.A. (1986). Neighborhoods of words in the mental lexicon. Unpublished doctoral<br />

dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington.<br />

Luce, P.A., & Cluff, M.S. (1998). Delayed commitment in spoken word recognition: Evidence<br />

from cross-modal priming. Perception & Psychophysics, 60, 484–490.<br />

Luce, P.A., & Lyons, E.A. (1999). Processing lexically embedded spoken words. Journal of<br />

Experimental Psychology: Human, Perception <strong>and</strong> Performance, 25, 174–183.<br />

Luce, P.A., Pisoni, D.B, & Goldinger, S.D. (1990). Similarity neighborhoods of spoken words.<br />

In G.T.M Altmann (Ed.), <strong>Cognitive</strong> models of speech processing, pp. 122–147. Cambridge,<br />

MA: MIT Press.<br />

Marslen-Wilson, W.D. (1987). Functional parallelism in spoken word recognition. Cognition,<br />

25, 71–102.<br />

Marslen-Wilson, W.D. (1990). Activation, competition, <strong>and</strong> frequency in lexical access. In<br />

G.T.M Altmann (Ed.), <strong>Cognitive</strong> models of speech processing, pp. 148–172. Cambridge,<br />

MA: MIT Press.<br />

Marslen-Wilson, W.D., & Welsh, A. (1978). Processing interactions <strong>and</strong> lexical access during<br />

word recognition in continuous speech. <strong>Cognitive</strong> Psychology, 10, 29–63.<br />

McClell<strong>and</strong>, J.L., & Elman, J.L. (1986). The TRACE model of speech perception. <strong>Cognitive</strong><br />

Psychology, 18, 1–86.<br />

Monsell, S., & Hirsh, K.W. (1998). Competitor priming in spoken word recognition. Journal of<br />

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, <strong>and</strong> Cognition, 24, 1495–1520.<br />

Norris, D.G. (1994). Shortlist: A connectionist model of continuous speech recognition.<br />

Cognition, 52, 189–234.<br />

Prather, P., & Swinney, D. (1977). Some effects of syntactic context upon lexical access. 85th<br />

Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco.

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

386 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

Radeau, M. (1995). Facilitation <strong>and</strong> inhibition in phonological priming. 36th Annual Meeting<br />

of the Psychonomic Society, Los Angeles.<br />

Radeau, M., Morais, J., & Dewier, A. (1989). Phonological priming in spoken word<br />

recognition: Task effects. Memory <strong>and</strong> Cognition, 17, 525–535.<br />

Radeau, M., Morais, J., & Segui, J. (1995). Phonological priming between monosyllabic<br />

spoken words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human, Perception <strong>and</strong> Performance,<br />

21, 1297–1311.<br />

Radeau, M., Segui, J., & Morais, J. (1994). The effect of overlap position in phonological<br />

priming between spoken words. In Proceedings of 1994 international Conference on spoken<br />

<strong>Language</strong> Processing, Vol. 3, pp. 1419–1422. Yokohama, Japan: The Acoustical Society of<br />

Japan.<br />

Shillcock, R. (1990). Lexical hypotheses in continuous speech. In G.T.M Altmann (Ed.),<br />

<strong>Cognitive</strong> models of speech processing, pp. 24–49. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.<br />

Slowiaczek, L.M., & Hamburger, M.B. (1992). Prelexical facilitation <strong>and</strong> lexical interference<br />

in auditory word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, <strong>and</strong><br />

Cognition, 18, 1239–1250.<br />

Slowiaczek, L.M., Nusbaum, H.C., & Pisoni, D.B. (1987). Phonological priming in auditory<br />

word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, <strong>and</strong> Cognition,<br />

13, 64–75.<br />

Slowiaczek, L.M., Soltano, E., & McQueen, J.M. (1997). Facilitation of spoken word<br />

processing: only a rime can prime. Abstracts of the 38th Annual Meeting of the<br />

Psychonomic Society, pp. 39, Philadelphia, PA.<br />

Vroomen, J., & de Gelder, B. (1997). The activation of embedded words in spoken word<br />

recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception <strong>and</strong> Performance, 23,<br />

710–720.<br />

Zwitserlood, P. (1989). The locus of the effects of sentential-semantic context in spoken-word<br />

processing. Cognition, 32, 25–64.<br />

APPENDIX A<br />

Material used as targets <strong>and</strong> as beginning, nal <strong>and</strong> control primes in Experiments 1a <strong>and</strong> 3.<br />

Word targets Beginning Final Control<br />

carcasse [karkas] car [kar] casse [kAs] bien<br />

cartable [kartabl] car [kar] table [tabl] loin<br />

corniche [kOrniS] cor [kOr] niche [niS] cuve<br />

coulisse [kulis] cou [ku] lisse [lis] oeuf<br />

critique [kritik] cri [kri] tique [tik] cave<br />

poubelle [pubEl] pou [pu] belle [bEl] coin<br />

tournage [turnaZ] tour [tur] nage [naZ] mise<br />

troupeau [trupo] trou [tru] peau [po] juge<br />

verveine [vErvEn] ver [vEr] veine [vEn] lm<br />

pincette [pe˜EsEt] pin [pE] cette [sEt] chef<br />

parcours [parkur] par [par] cours [kur] face<br />

mouchoir [muSwar] mou [mu] choir [Swar] foin<br />

arctique [arktik] arc [ark] tique [tik] lobe<br />

corbeau [kOrbo] cor [kOr] beau [bo] plan<br />

carnage [karnaZ] car [kar] nage [naZ] rire<br />

chardon [SardcÕ] char [Sar] don [dcÕ] vase<br />

dégaine [degEn] dé [de] gaine [gEn] puce<br />

soudure [sudyr] sou [sud] dure [dyr] zone

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 387<br />

vermine [vErmin] ver [vEr] mine [min] ruse<br />

corsage [kOrsaZ] cor [kOr] sage [saZ] lien<br />

boisson [bwascÕ] bois [bwa] son [scÕ] acte<br />

cassure [kAsyr] cas [kA] sure [syr] rêve<br />

massage [masaZ] mas [mA] sage [saZ] rive<br />

soutien [sutje˜E] sou [su] tien [tje˜E] rime<br />

charbon [SarbcÕ] char [Sar] bon [bcÕ] nuit<br />

voltige [vOltiZ] vol [vOl] tige [tiZ] base<br />

vertige [vErtiZ] ver [vEr] tige [tiZ] brin<br />

couvert [kuvEr] cou [ku] vert [vEr] arme<br />

verdure [vErdyr] ver [vEr] dure [dyr] noce<br />

cordon [kOrdcÕ] cor [kOr] don [dcÕ] fade<br />

moulin [mule˜E] mou [mu] lin [le˜E] lion<br />

pinson [pe˜EscÕ] pin [pe˜E] son [scÕ] bord<br />

débile [debil] dé [de] bile [bil] muse<br />

passeport [pAspOr] passe [pAs] port [pOr] aide<br />

pourboire [purbwar] pour [pur] boire [bwar] joie<br />

trousseau [truso] trou [tru] seau [so] oeil<br />

Pseudoword targets Beginning Final Control<br />

tromasse trot masse veau<br />

pourvent pour vent choc<br />

racycle rat cycle vide<br />

mouvanne mou vanne cote<br />

ormonde or monde cran<br />

graterre gras terre dalle<br />

borvie bord vie date<br />

caldure cale dure dome<br />

chassot chat seau fêve<br />

poulmar poule mare an<br />

garsoin gare soin loge<br />

lipoire lit poire luge<br />

crudale cru dalle miel<br />

murdose mur dose ocre<br />

criboue cri boue ogre<br />

tarbeau tare beau onde<br />

rafoule rat foule orge<br />

farseau phare seau anse<br />

torvain tort vin ame<br />

glutique glu tique bec<br />

grutonne grue tonne axe<br />

troumale trou male blé<br />

lourire loup rire bus<br />

murcire mur cire cap<br />

morcave mort cave coq<br />

poupier pou pied feu<br />

orvile or ville lac<br />

poitaux poids taux roc<br />

sanpore sang port sac<br />

griloque gris loque sec<br />

pourfeinte pour feinte ski

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

388 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

ferloup fer loup sud<br />

platrame plat trame rite<br />

plicage pli cage vote<br />

taurate taux rate zèle<br />

ruclan rue clan bave<br />

APPENDIX B<br />

Material used as targets <strong>and</strong> as beginning, nal <strong>and</strong> control primes in Experiment 1b<br />

Word targets Beginning Final Control<br />

cravate cra vate dule<br />

colline co line jaic<br />

navette na vette dri<br />

chevreuil che vreuil pade<br />

clivage cli vage bre<br />

tragique tra gique blu<br />

bronzage bron zage sca<br />

cloison cloi zon ruc<br />

gorille go rille daf<br />

turquoise tur quoise gli<br />

tranquille tran quil duce<br />

nation na tion dif<br />

tisane ti zane blo<br />

comique co mique spa<br />

nature na ture ric<br />

chenille che nille clon<br />

berceuse ber ceuse cli<br />

damier da mier cron<br />

échette é chette ja<br />

blindage blin dage pru<br />

glissiere gli ciere dro<br />

clavier cla vier dre<br />

breuvage breu vage glin<br />

anelle a nelle sti<br />

timide ti mide cra<br />

cochon co chon bla<br />

narine na rine drou<br />

cheville che ville fabe<br />

branchage bran chage noc<br />

blizzard bli zard nof<br />

reptile rep tile a<br />

glaciaire gla ciaire in<br />

grenade gre nade duf<br />

praline pra line dui<br />

stupide stu pide dron<br />

colombe co lombe be

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

PHONOLOGICAL PRIMING 389<br />

Pseudoword targets Beginning Final Control<br />

cratile cra tile daif<br />

chenupe che nupe bli<br />

spadran spa dran clu<br />

stirane sti rane blin<br />

drofule dro fule drane<br />

bredille bre dille bune<br />

vrinoule vri noule gleu<br />

franale fra nale spui<br />

cofule co fule clir<br />

varpide var pide sco<br />

nurvade nur vade c<br />

jocride jo cride vra<br />

jalide ja lide doin<br />

clapron cla pron fouc<br />

clidrone cli drone on<br />

gurette gu rette doce<br />

drifune dri fune vro<br />

prabune pra bune spo<br />

vrapime vra pime fuc<br />

guvlon gu vlon de<br />

joklon jo klon tru<br />

frulipe fru lipe gate<br />

daprin da prin jo<br />

frodace fro dace spu<br />

gunole gu nole cade<br />

jatran ja tran dof<br />

croutile crou tile tra<br />

drefoge dre foge lane<br />

choncade chon cade jic<br />

chonrice chon rice jal<br />

tuimave tui mave joc<br />

crondile cron dile juc<br />

javuce ja vuce treu<br />

frucade fru cade jode<br />

plouvade plou vade laic<br />

trugote tru gote line

Downloaded By: [Universitaetsbibliothek] At: 15:27 19 June 2007<br />

390 SPINELLI, SEGUI AND RADEAU<br />

APPENDIX C<br />

Material used as targets <strong>and</strong> as beginning, nal <strong>and</strong> control primes in Experiment 2<br />

Word Targets Partial primes Bisyllabic primes<br />

Beginning Final Control Beginning Final Control<br />

R<br />

carcasse car casse bien cartouche [kartuS] bécasse [bekas] stature<br />

cartable car table loin carpette [karpEt] comptable [kcÕtabl] chevreuil<br />

corniche cor niche cuve cordage [kOrdAZ] péniche [peniS] lav<strong>and</strong>e<br />

coulisse cou lisse oeuf couture [kutyr] pelisse [p@lis] oeillière<br />

critique cri tique cave crinière [krinjEr] boutique [butik] monnaie<br />

poubelle pou belle coin poussin [puse˜E] rebelle [r@bEl] savate<br />

tournage tour nage mise tourteau [turto] freinage [frEnaZ] calcium<br />

troupeau trou peau juge troubler [truble] drapeau [drapo] soupir<br />

verveine ver veine lm vertèbre [vErtEbr] déveine [devEn] brochet<br />

pincette pin cette chef pingouin [pe˜Egwe˜E] facette [fasEt] intrus<br />

parcours par cours face parcelle [parsEl] concours [kcÕkur] moteur<br />

mouchoir mou choir foin mourant [murñA] perchoir [pErSwar] écaille<br />

arctique arc tique lobe arcade [arkad] moustique [mustik] pantoue<br />

corbeau cor beau plan cornet [kOrnE] ambeau [ñAbo] riposte<br />

carnage car nage rire carbone [karbOn] lainage [lEnaZ] tremplin<br />

chardon char don vase chargeur [SarZør] dindon [de˜EdcÕ] biceps<br />

dégaine dé gaine puce déclic [deklik] rengaine [rñAgEn] corneille<br />

soudure sou dure zone souillon [sujcÕ] bordure [bOrdyr] présage<br />

vermine ver mine ruse version [vErsjcÕ] famine [famin] rouleau<br />

corsage cor sage lien cortège [kOrtEZ] message [mesaZ] ancêtre<br />