Desert Magazine Book Shop - Desert Magazine of the Southwest

Desert Magazine Book Shop - Desert Magazine of the Southwest

Desert Magazine Book Shop - Desert Magazine of the Southwest

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

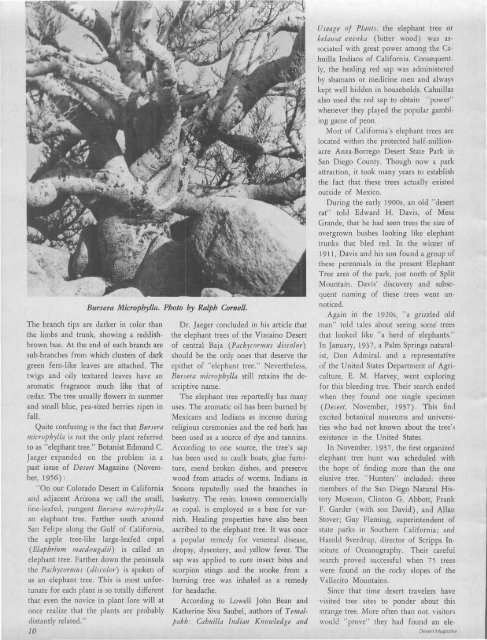

Bursera Microphylla. Photo by Ralph Cornell.<br />

The branch tips are darker in color than<br />

<strong>the</strong> limbs and trunk, showing a reddishbrown<br />

hue. At <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> each branch are<br />

sub-branches from which clusters <strong>of</strong> dark<br />

green fern-like leaves are attached. The<br />

twigs and oily textured leaves have an<br />

aromatic fragrance much like that <strong>of</strong><br />

cedar. The tree usually flowers in summer<br />

and small blue, pea-sized berries ripen in<br />

fall.<br />

Quite confusing is <strong>the</strong> fact that Bursera<br />

microphylla is not <strong>the</strong> only plant referred<br />

to as "elephant tree." Botanist Edmund C.<br />

Jaeger expanded on <strong>the</strong> problem in a<br />

past issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Desert</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> (November,<br />

1956):<br />

"On our Colorado <strong>Desert</strong> in California<br />

and adjacent Arizona we call <strong>the</strong> small,<br />

fine-leafed, pungent Bursera microphylla<br />

an elephant tree. Far<strong>the</strong>r south around<br />

San Felipe along <strong>the</strong> Gulf <strong>of</strong> California,<br />

<strong>the</strong> apple tree-like large-leafed copal<br />

(Elaphrium macdougalii) is called an<br />

elephant tree. Far<strong>the</strong>r down <strong>the</strong> peninsula<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pachycormus {discolor) is spoken <strong>of</strong><br />

as an elephant tree. This is most unfortunate<br />

for each plant is so totally different<br />

that even <strong>the</strong> novice in plant lore will at<br />

once realize that <strong>the</strong> plants are probably<br />

distantly related."<br />

10<br />

Dr. Jaeger concluded in his article that<br />

<strong>the</strong> elephant trees <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vizcaino <strong>Desert</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> central Baja (Pachycormus discolor)<br />

should be <strong>the</strong> only ones that deserve <strong>the</strong><br />

epi<strong>the</strong>t <strong>of</strong> "elephant tree." Never<strong>the</strong>less,<br />

Bursera microphylla still retains <strong>the</strong> descriptive<br />

name.<br />

The elephant tree reportedly has many<br />

uses. The aromatic oil has been burned by<br />

Mexicans and Indians as incense during<br />

religious ceremonies and <strong>the</strong> red bark has<br />

been used as a source <strong>of</strong> dye and tannins.<br />

According to one source, <strong>the</strong> tree's sap<br />

has been used to caulk boats, glue furniture,<br />

mend broken dishes, and preserve<br />

wood from attacks <strong>of</strong> worms. Indians in<br />

Sonora reputedly used <strong>the</strong> branches in<br />

basketry. The resin, known commercially<br />

as copal, is employed as a base for varnish.<br />

Healing properties have also been<br />

ascribed to <strong>the</strong> elephant tree. It was once<br />

a popular remedy for venereal disease,<br />

dropsy, dysentery, and yellow fever. The<br />

sap was applied to cure insect bites and<br />

scorpion stings and <strong>the</strong> smoke from a<br />

burning tree was inhaled as a remedy<br />

for headache.<br />

According to Lowell John Bean and<br />

Ka<strong>the</strong>rine Siva Saubel, authors <strong>of</strong> Temalpakh:<br />

Cahuilla Indian Knowledge and<br />

Useage <strong>of</strong> Plants, <strong>the</strong> elephant tree or<br />

kelawat enenka (bitter wood) was associated"<br />

with great power among <strong>the</strong> Cahuilla<br />

Indians <strong>of</strong> California. Consequently,<br />

<strong>the</strong> healing red sap was administered<br />

by shamans or medicine men and always<br />

kept well hidden in households. Cahuillas<br />

also used <strong>the</strong> red sap to obtain "power"<br />

whenever <strong>the</strong>y played <strong>the</strong> popular gambling<br />

game <strong>of</strong> peon.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> California's elephant trees are<br />

located within <strong>the</strong> protected half-millionacre<br />

Anza-Borrego <strong>Desert</strong> State Park in<br />

San Diego County. Though now a park<br />

attraction, it took many years to establish<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>se trees actually existed<br />

outside <strong>of</strong> Mexico.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> early 1900s, an old "desert<br />

rat" told Edward H. Davis, <strong>of</strong> Mesa<br />

Grande, that he had seen trees <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong><br />

overgrown bushes looking like elephant<br />

trunks that bled red. In <strong>the</strong> winter <strong>of</strong><br />

1911, Davis and his son found a group <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se perennials in <strong>the</strong> present Elephant<br />

Tree area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> park, just north <strong>of</strong> Split<br />

Mountain. Davis' discovery and subsequent<br />

naming <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se trees went unnoticed.<br />

Again in <strong>the</strong> 1920s, "a grizzled old<br />

man" told tales about seeing some' trees<br />

that looked like "a herd <strong>of</strong> elephants."<br />

In January, 1937, a Palm Springs naturalist,<br />

Don Admiral, and a representative<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture,<br />

E. M. Harvey, went exploring<br />

for this bleeding tree. Their search ended<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y found one single specimen<br />

(<strong>Desert</strong>, November, 1937). This find<br />

excited botanical museums and universities<br />

who had not known about <strong>the</strong> tree's<br />

existence in <strong>the</strong> United States.<br />

In November, 1937, <strong>the</strong> first organized<br />

elephant tree hunt was scheduled with<br />

<strong>the</strong> hope <strong>of</strong> finding more than <strong>the</strong> one<br />

elusive tree. "Hunters" included: three<br />

members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> San Diego Natural History<br />

Museum, Clinton G. Abbott, Frank<br />

F. Garder (with son David), and Allan<br />

Stover; Guy Fleming, superintendent <strong>of</strong><br />

state parks in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California; and<br />

Harold Sverdrup, director <strong>of</strong> Scripps Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> Oceanography. Their careful<br />

search proved successful when 75 trees<br />

were found on <strong>the</strong> rocky slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Vallecito Mountains.<br />

Since that time desert travelers have<br />

visited tree sites to ponder about this<br />

strange tree. More <strong>of</strong>ten than not, visitors<br />

would "prove" <strong>the</strong>y had found an ele-<br />

Deserr <strong>Magazine</strong>