TABLE OF CONTENTS - National Zoo

TABLE OF CONTENTS - National Zoo

TABLE OF CONTENTS - National Zoo

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

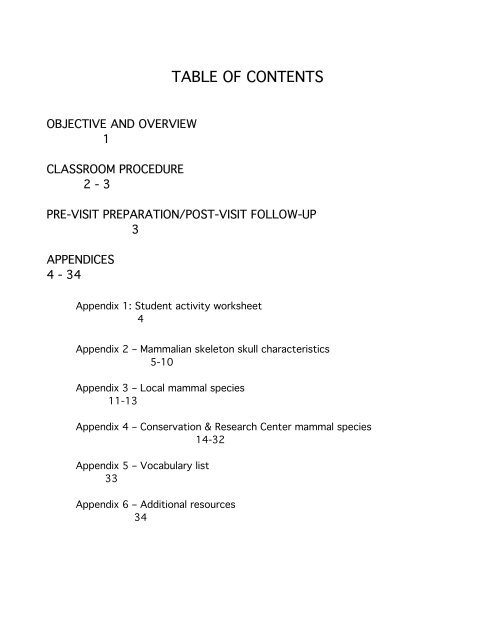

OBJECTIVE AND OVERVIEW<br />

1<br />

CLASSROOM PROCEDURE<br />

2 - 3<br />

<strong>TABLE</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>CONTENTS</strong><br />

PRE-VISIT PREPARATION/POST-VISIT FOLLOW-UP<br />

3<br />

APPENDICES<br />

4 - 34<br />

Appendix 1: Student activity worksheet<br />

4<br />

Appendix 2 – Mammalian skeleton skull characteristics<br />

5-10<br />

Appendix 3 – Local mammal species<br />

11-13<br />

Appendix 4 – Conservation & Research Center mammal species<br />

14-32<br />

Appendix 5 – Vocabulary list<br />

33<br />

Appendix 6 – Additional resources<br />

34

Topic: Diet and Dentition.<br />

CONSERVATION & RESEARCH CENTER<br />

Educational Outreach Program<br />

“What’s for Lunch?”<br />

Teacher Guide<br />

Virginia Standards of Learning (SOLs) for Science targeted:<br />

SOL 3.1.a,b,c,d,e,g – Scientific Investigation, Reasoning, and Logic<br />

The student will plan and conduct investigations in which<br />

a. questions are developed to formulate hypotheses;<br />

b. predictions and observations are made;<br />

c. data are gathered, charted, and graphed;<br />

d. objects with similar characteristics are classified into at least two sets and<br />

two subsets;<br />

e. inferences are made and conclusions are drawn;<br />

g. length is measured to the nearest centimeter;<br />

SOL 3.5.b – Living Systems<br />

The student will investigate and understand relationships among organisms in<br />

aquatic and terrestrial food chains. Key concepts include<br />

b. herbivore, carnivore, omnivore<br />

Objective:<br />

To teach students about how scientists study the three consumer categories<br />

(herbivore, carnivore, omnivore). Emphasis will be placed on using the scientific<br />

method to determine consumer category based on dentition. This will create an<br />

awareness of how the structure and function of different types of teeth relate to the<br />

kinds of foods animals eat. This project will involve students directly in<br />

understanding animal systems and relating these concepts to their own world.<br />

Overview:<br />

This module has three sections. The first section will teach the students about the<br />

different functions of their own teeth (incisors = cutters, canines = tearers, molars =<br />

grinders). The second section will introduce the students to the concepts of<br />

herbivore, carnivore, and omnivore. They will define each of these consumer<br />

1

categories by observing teeth in the skulls of animals they might see in local<br />

habitats, including an herbivore (beaver), carnivore (fox), and omnivore (raccoon).<br />

The final section allows the students to become scientists/investigators. There will<br />

be several unknown skulls that the students have an opportunity to investigate.<br />

They will collect data on each skull (including skull measurements, tooth structure<br />

and counts) and they will develop hypotheses about what each animal might eat and<br />

why. They will test their hypothesis by attempting to identify the species through a<br />

comparison of their data to information found in a CRC Mammal Identification Guide.<br />

Finally, the class will reconvene to review important concepts learned during the<br />

exercise.<br />

Classroom Procedure:<br />

Orientation to project:<br />

1. Introduce CRC and its conservation breeding and research programs.<br />

2. Define the terms “diet” and “dentition”.<br />

Section One: Identify structure and function of human teeth<br />

This presentation provides an introduction to the students’ own diet and dentition.<br />

1. Students identify the types of teeth by comparing their own teeth (observed in a<br />

mirror) to the diagram of a mouth found on page one of the student booklet.<br />

• Number 1 teeth have flat bottoms. They are called “incisors” and are used to<br />

cut (like a pair of scissors or a knife) into fruits and vegetables.<br />

• Next are the number 2 teeth, called “canines”. Note the sharp point. These<br />

are used to tear meat, like when you tear chicken off of the bone.<br />

• Last are the number 3 and 4 teeth called premolars and molars. Premolars and<br />

molars have bumps (called cusps). Molars grind food using the bumps, like<br />

when we grind up a peanut.<br />

2. Review: Notice the teeth had three different kinds of shapes. That’s because<br />

there are three different kinds of jobs (functions) for teeth to do:<br />

• The incisors, or flat teeth, are cutters. They are flat like the edge of scissors<br />

that cut, like when they cut into a sandwich or lettuce.<br />

• The canine teeth with points are tearers. They tear food, like when you tear<br />

chicken off of the chicken bone.<br />

• The premolars and molars with the bumps are grinders. They grind up the<br />

food, like when you eat peanuts.<br />

2

Section Two: Local mammals and consumer categories<br />

1. Using posters and skulls of local mammal species (herbivore – beaver; carnivore –<br />

red fox; omnivore – raccoon), the leader will introduce the concepts of consumer<br />

categories and the differences in dentition.<br />

2. Ask students questions to reinforce that you can tell what an animal eats based<br />

on the teeth present. For example, if they found a skull with mostly pointed<br />

teeth, what would it eat? Answer: meat. It would be a carnivore. If a<br />

student/scientist found a skull with many cutters and bumpy molars, what would<br />

it eat? Answer: vegetables and fruits. It would be a herbivore.<br />

Section Three: Unknown skull stations; investigate using the scientific method<br />

1. The leader will explain how scientists collect data to understand consumer<br />

categories.<br />

2. Using the skulls of local animals (beaver, red fox, raccoon), the leader will explain<br />

how scientists collect data on skull size and structure and then form a hypothesis<br />

regarding consumer category based on their knowledge of how diet relates to<br />

dentition.<br />

3. Class is divided up into teams of 3 – 5 students each and sent to an “unknown”<br />

skull station. Students should be reminded to cooperate with their teammates,<br />

as any scientist would, when performing their investigations. Emphasize that the<br />

skulls are extremely delicate and should be handled with care to avoid accidents.<br />

4. At each station, student teams determine the consumer category of the animal<br />

based on the dentition observed in the skull. Students must observe the skulls,<br />

collect data, and develop hypotheses using the data sheet provided in their<br />

student booklets. They must decide, based on the data they collected, whether<br />

the animal is an herbivore, carnivore, or omnivore. Once they have done this,<br />

they test their hypothesis by looking up the actual identity of the animal in the<br />

CRC Mammal Identification Guide.<br />

5. Allow 4-6 minutes at each station and rotate stations.<br />

6. Class reconvenes to briefly discuss the students’ findings at each station and<br />

correctly identify each species.<br />

7. Class concludes with a dialog about what the students learned in this session.<br />

Emphasis will be placed on the fact that students were able to figure out what an<br />

animal might eat based on the different teeth it has. They used the scientific<br />

methods used by Smithsonian scientists such as nutritionists at the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Zoo</strong><br />

or paleontologists at the Natural History Museum.<br />

Pre-Visit Preparation/Post-Visit Follow-Up:<br />

3

Students should be familiar with the general concepts of diet, dentition and<br />

consumer groups in preparation for the visit from CRC staff. The appendices include<br />

information on: (1) mammalian skeleton skull characteristics, (2) local mammal<br />

species, (3) Conservation & Research Center mammal species, (4) vocabulary list,<br />

and (5) additional resources. These resources can assist teachers in creating lesson<br />

plans on diet vs. dentition and incorporating this outreach program into school<br />

curriculum.<br />

4

Appendix 2: Mammalian skeleton skull characteristics<br />

(The following is a technical excerpt from the Handbook to the Orders and Families<br />

of Living Mammals by Timothy E. Lawlor.)<br />

The skull consists of a series of bones encasing the brain and nasal cavities and<br />

forming the upper jaw, collectively making up the cranium and the lower jaw, or<br />

mandible. Variations in overall shape of the skull among mammals results from<br />

evolutionary changes in jaw function and associated musculature, brain size and<br />

proportions, size and shape of the bony housing of the ear (auditory bulla), and<br />

other features. With the exception of certain elements in the cranium of cetaceans,<br />

the bones making up the skull retain the same positions relative to one another.<br />

However, there is substantial variation in the size and shape of individual bones.<br />

Therefore, it is important to compare skull features for a variety of different<br />

mammals in order to appreciate the diversity of skull structure. For this reason, skull<br />

outlines are provided for three distinctly different mammals (Fig. 1).<br />

6

Figure 1. Skulls of a cat (A), a rodent (B), and a porpoise (C). Abbreviations are as follows: AB,<br />

auditory bulla; Alis, alisphenoid; AngP, angular process; Baso, basioccipital; Bass, basisphenoid; C,<br />

canine; ConP, condyloid process; CorP, coronoid process; FM, foramen magnum; Fr, frontal; I, incisor;<br />

Int, interparietal; IC, infraorbital canal; Ju, jugal; Lac, lacrimal; M, molar; ManF, mandibular fossa; MasF,<br />

masseteric fossa; MasP, mastoid process; Mx, maxilla; Na, nasal; O, orbit; Occ, occipital; Orb,<br />

orbitosphenoid; PM, premolar; Pal, palatine; Par, parietal; ParP, paroccipital process; Pmx, premaxilla;<br />

PooP, postorbital process; Pre, presphenoid; Pt, pterygoid; Sq, squamosal; TemF, temporal fossa; Vo,<br />

vomer.<br />

7

General features of the cranium<br />

Braincase - That portion of the cranium encasing the brain. It is largest relative to<br />

other parts of the skull in primates (e.g., Hominidae).<br />

Rostrum - That portion of the cranium extending anteriorly from the front edge of<br />

the orbits (see below) or base of the zygomatic arch (see below). It corresponds to<br />

the externally visible muzzle or snout, and includes the upper jaw and bones<br />

surrounding the nasal cavity. The rostrum is especially elongate in cetaceans,<br />

anteaters, pangolins, bandicoots, and nectar-feeding bats, among others.<br />

Dorsal aspect of the cranium<br />

Nasal bones - Paired bones forming the anteriormost roof of the nasal cavities. In<br />

some mammals these bones are absent or are very small and do not roof the nasal<br />

passages (Fig. 1C).<br />

Premaxillae (premaxillary bones) - A pair of bones forming the lower margin of the<br />

outer nasal openings and anteriormost portion of the roof of the mouth, or palate.<br />

The upper incisor teeth always reside on these bones. In most mammals each<br />

premaxilla has an elongate process extending along one side of the nasal cavity<br />

(nasal process or branch) and a second process meeting the other premaxilla at the<br />

midline of the palate (palatal process or branch). The premaxillae fuse with the<br />

maxillae in some mammals (e.g., some primates and edentates).<br />

Maxillae (maxillary bones) - These two tooth-bearing bones make up a large part of<br />

the sides of the rostrum and the palate posterior to and adjoining the premaxillae.<br />

They are especially large and elongate in cetaceans (Fig. 1C). The anterior base of<br />

each zygomatic arch (see below) usually consists of an extension of the maxilla,<br />

termed the zygomatic process of the maxilla.<br />

Frontal bones - A pair of bones just posterior to the nasals and dorsal to the<br />

maxillae. They vary in size. The antlers and horns of artiodactyls are growths of the<br />

frontal bones. In many mammals, each frontal bone has a lateral pointed projection,<br />

the postorbital process, which marks the posterior border of the orbit.<br />

Parietal bones - Located posterior to the frontals, these paired bones form the bulk<br />

of the roof of the braincase. In certain primates they are very large.<br />

Interparietal bone - When distinct, this is a single, often triangular-shaped bone<br />

centrally located on the braincase at the posterior juncture of the parietal bones.<br />

9

Often it is fused with the occipital bone (see below) in adults. Rodents generally<br />

have a prominent interparietal (Fig. 1B).<br />

Squamosal bones - Each of these two bones is located lateral and ventral to the<br />

corresponding parietal bone. Each squamosal bears a ventral articular surface, the<br />

mandibular fossa, that forms part of the hinge supporting the lower jaw. The<br />

posterior base of the zygomatic arch consists of the zygomatic process of the<br />

squamosal. When the squamosal is fused with the tympanic bone the complex is<br />

termed the temporal bone; this fusion is found in most mammals.<br />

Jugal bones - Each of these two bones forms the central portion of the zygomatic<br />

arch (see below) and is located between the zygomatic processes of the maxilla and<br />

squamosal. Occasionally the jugal also is in contact with the lacrimal bone (e.g., in<br />

many rodents) or the premaxilla. When the zygomatic arch is absent or incomplete,<br />

the jugal often is absent.<br />

Zygomatic arches - Conspicuous arches on the sides of the cranium that form the<br />

lateral and ventral borders of the orbits and temporal fossae. Several bones,<br />

including the maxilla, jugal, squamosal, and lacrimal may contribute to each arch.<br />

Jaw muscles (masseters) have their origins on the surface of the arch. In many<br />

rodents the anterior portion of the arch is tilted upward and forms a broad plate<br />

(zygomatic plate).<br />

Orbits - The socket-like depressions, one on each side of the cranium, in which the<br />

eyes are housed. Each orbit is bordered anteriorly and laterally by the zygomatic<br />

arch and posteriorly by the temporal fossa.<br />

Temporal fossae - These depressions are located posterior to the orbits and are<br />

bordered laterally by the zygomatic arches. In some primates and in horses the<br />

temporal fossa and orbit are separated by a postorbital plate, thus forming two<br />

compartments.<br />

Lacrimal bones - Each of these bones is located on or adjacent to the anterior base<br />

of the zygomatic arch at its dorsal edge. Usually small, these bones can be<br />

identified by the presence in each of the lacrimal foramen, an opening for the tear<br />

duct.<br />

Occipital (lambdoidal) crest - A ridge of variable size extending across the<br />

posterodorsal margin of the cranium. It is usually part of the supraoccipital bone<br />

(see below). This crest forms an area of attachment for neck muscles and ligaments<br />

in large-headed forms.<br />

10

Sagittal crest - A vertical ridge extending along the dorsal midline of the posterior<br />

portion of the braincase. It is variable in extent, occurring to a lesser degree on<br />

occipital, interparietal, and parietal bones, and is most prominent in mammals<br />

requiring an expanded surface area for large temporal muscles.<br />

Posterior aspect of the cranium<br />

Foramen magnum - A large opening in the occipital bone through which pass the<br />

spinal cord and vertebral arteries.<br />

Supraoccipital bone - The part of the occipital bone overlying the foramen magnum.<br />

When present, the occipital crest is at the dorsal edge of this bone.<br />

Basioccipital bone - A single bone ventral to the foramen magnum and extending<br />

anteriorly on the ventral surface of the cranium between the auditory bullae.<br />

Exoccipital bones - Each of these bones is located lateral to the foramen magnum<br />

and bears andoccipital condyle.<br />

Occipital condyles - Paired swellings of the exoccipital bones adjacent to the foramen<br />

magnum, each of which articulates with the first cervical vertebra (atlas).<br />

Paroccipital processes - Each of these processes is a ventrally extending projection<br />

of the occipital bone lying just posterior to and usually in close association with the<br />

auditory bulla (see below). Largest in herbivores (Fig. 1B), these processes provide<br />

sites of origin for large digastric muscles necessary for grinding plant material.<br />

Mastoid bones - Small, usually obscure bones adjacent to the paroccipital processes<br />

and at the posterior margins of the auditory bullae. The mastoid is a portion of the<br />

concealed periotic bone (a bone protecting the inner ear) exposed on the surface of<br />

the skull. In certain mammals it protrudes as the mastoid process (Fig. 1A).<br />

Ventral aspect of the cranium<br />

Auditory bullae - Thin-walled, swollen capsules of bone on each side of the<br />

basioccipital bone and ventral to the squamosal. Each bulla consists of the tympanic<br />

bone or a fusion of the tympanic and entotympanic bones. The mastoid and<br />

alisphenoid (see below) may also participate in its formation. The bullae protect the<br />

middle-ear ossicles and facilitate efficient transmission of sound to the inner ear.<br />

They become enormously inflated in many mammals (particularly some groups of<br />

rodents) that are adapted to open plains or deserts and have acute hearing. In<br />

others the bullae are absent or are incomplete and the ear is surrounded by a bony<br />

11

ing made up of the tympanic bone (e.g., some insectivores). The bullae are very<br />

loosely attached to the skull in cetaceans, an adaptation that probably enhances<br />

reception of water-borne signals by reducing transmission of sound to the bulla from<br />

other parts of the skull.<br />

Basisphenoid bone - A single bone in the midline just anterior to the basioccipital.<br />

Presphenoid bone - A median bone which is usually visible anterior to the<br />

basisphenoid. It is fused with the orbitoshenoids which extend laterally into the<br />

posterior wall of the orbits.<br />

Alisphenoid bones - Wing-like bones in the walls of the temporal fossae posterior to<br />

the frontal and orbitosphenoid bones and anterior to the squamosals. In marsupials<br />

the alisphenoids are very large and participate in the formation of the auditory<br />

bullae. An alisphenoid canal, which transmits part of the fifth cranial nerve, a<br />

diagnostic character in some mammals, may penetrate a bony shelf at the ventral<br />

base of the alisphenoid bone.<br />

Pterygoid bones - Each of these bones lies posterior to the internal opening of the<br />

nasal passages. An elongate process (the hamular process) usually extends<br />

posteriorly from the ventral surface of each bone. The pterygoids are unusually<br />

large and distinctively shaped in odontocetes (Fig. 1C). They are often fused with<br />

the alisphenoid in other mammals.<br />

Palatine bones - These are paired bones that form the posterior portion of the<br />

palate. They lie between the cheekteeth (see below) and are posterior to the<br />

maxillae.<br />

Vomer - The bone forming the posteroventral part of the wall separating the two<br />

sides of the nasal passages. This bone is usually obscure but it appears occasionally<br />

as part of the palate.<br />

Lower jaw or mandible<br />

Dentary bones - The lower jaws consist of two halves, or dentary bones united either<br />

firmly (most mammals) or loosely (e.g., rodents) in a symphysis at the anterior end.<br />

Coronoid process - The projection extending dorsally from each half of the jaw into<br />

the temporal fossa. It is largest in mammals with large temporal muscles (Fig. 1A);<br />

it is small or absent in certain herbivores (e.g., some rodents).<br />

12

Condyloid process - The projection on the upper rear portion of the mandible bearing<br />

the mandibular condyle. The latter articulates with the upper jaw at the mandibular<br />

fossa of the squamosal bone. The condyle varies substantially in shape because of<br />

differing patterns of jaw movement involved with different dietary requirements. In<br />

some carnivores (e.g., Mustelidae (black-footed ferrets)) the hinge formed at the<br />

joint is firmly constructed and the lower jaw can be removed form the upper jaw only<br />

with difficulty. This adaptation prevents disarticulation of the mandible as the<br />

predator struggles with its prey. In herbivores the joint tends to be loose in order to<br />

allow the flexibility of jaw motion necessary for grinding coarse vegetative matter.<br />

Angular process - A process of variable size at the posteroventral edge of the lower<br />

jaw. It is enormous in some herbivores, particularly rodents, providing a large<br />

surface area for insertion of the masseter muscles. Marsupials and some rodents are<br />

characterized by an angular process that is markedly inflected (bent inward), thus<br />

providing a large area of insertion for the jaw muscles.<br />

Masseteric fossa - The lateral depression of the lower jaw ventral to the coronoid<br />

process into which much of the masseter muscle inserts.<br />

Teeth<br />

Incisors - These teeth are the anteriormost teeth in the jaws of most mammals. The<br />

upper incisors reside wholly on the premaxillae. Incisors are ordinarily simple in<br />

structure but are modified in many mammals for grooming, cropping, cutting, and<br />

other functions.<br />

Canines - There is one pair of these stabbing teeth on both the upper and lower<br />

jaws. On the upper jaw each canine is located at the suture between the premaxilla<br />

and maxilla. The tusks found in many mammals are usually modified canines. Some<br />

mammals, particularly herbivores, lack canines and have a large gap, or diastema,<br />

between the incisors and premolars. In others the canines are poorly developed and<br />

peg-like.<br />

Cheekteeth - An inclusive term for all the teeth occurring in the cheek region. They<br />

include the premolars and molars of both jaws. The cheekteeth tend to be highcrowned<br />

(hypsodont) in mammals with course diets, such as grazers, and lowcrowned<br />

(brachydont) in mammals with soft diets, such as frugivores and omnivores.<br />

Details on these teeth follow.<br />

13

Premolars - These teeth are located just posterior to the canines. On the upper jaw<br />

they reside in the maxillae. They are large in herbivores, where they often closely<br />

resemble the molars in size and complexity, and in certain omnivores and carnivores.<br />

In the latter, the last upper premolar and first lower molar combine when occluded to<br />

form the principal shearing teeth (the carnassials).<br />

Molars - These are generally the most elaborate teeth in the dentition. In the upper<br />

jaw the molars are located in the maxillae. The molars are extremely variable in<br />

pattern. The three-cusped or tritubercular (tribosphenic) arrangement found in<br />

many marsupials, insectivores, and bats, is considered primitive for mammals. Each<br />

occluding pair of upper and lower molars functions as a set of “reversed triangles,”<br />

with the apexes pointing in opposite directions. The lower molars are more complex<br />

than the upper molars, consisting of a triangular anterior portion, the trigonid, and a<br />

squared posterior crushing surface, the “tail” or talonid. Tritubercular teeth are allpurpose<br />

teeth, providing both shearing and crushing surfaces. The addition of<br />

another prominent cusp on the upper molars results in a four-cusped or<br />

quadritubercular molar, an arrangement common in some insectivores and primates.<br />

Omnivores frequently have bunodont molars. Often basically quadritubercular, these<br />

teeth have low, rounded cusps. Effective crushing devices, they are found in pigs,<br />

bears, raccoons, and many primates (including humans). The secodont dentition of<br />

carnivores results from modification of certain cusps into an elaborate shearing<br />

mechanism. A lophodont dentition, present in most herbivores, is identified by<br />

ridges, or lophs, of enamel arranged in various ways between the cusps The tooth<br />

may vary from having a simple ring-like ridge around the margin to having a complex<br />

series of ridges and cross-ridges. When the ridges are formed in to two adjoining<br />

triangles or rings on the same tooth, the arrangement is called bilophodont, as in<br />

lagomorphs and some rodents. In most artiodactyls ridges of enamel take on a<br />

crescent shape, and for this reason the molars are termed selodont.<br />

14

Appendix 3: Local mammal species<br />

BEAVER<br />

(Castor canadensis)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: Beavers are among the largest rodents in the world. They are compact<br />

and heavyset with streamlined bodies, a flattened tail, and webbed feet for<br />

swimming. The sexes are about the same size. The unusually dense pelt consists of<br />

fine underfur overlaid with coarse guard hairs. The short, soft underfur usually has a<br />

slight tinge of lead color. The long, coarse, shiny guard hairs mask and protect the<br />

underfur. The coloration of the upper parts are brown to tawny. The tail and feet<br />

are black. Beavers cut down trees with their long, sharp front teeth and use the<br />

wood for food and for building dams across streams.<br />

Teeth: The incisor teeth of rodents grow throughout life. They have 4 incisors, 2<br />

above and 2 below. Canines and anterior premolars are lacking, leaving a space<br />

between the incisors and the cheek teeth. The number of teeth does not exceed<br />

22. The incisors are strongly developed, and the high-crowned cheek teeth<br />

(premolars and molars) have flat grinding surfaces and numerous enamel folds. The<br />

outer surface of the tooth is harder than the inner surface, much like a chisel, so<br />

that it is to some extent self-sharpening. The grinding, or cheek, teeth have many<br />

peculiar patterns when seen from above. The enamel, harder than dentine and<br />

cement, wears less rapidly and forms sharp ridges on the crown of the tooth. The<br />

space between the incisors and the cheek teeth permits maximum utilization of the<br />

gnawing front teeth and the manipulation of food when passed back to the grinding<br />

teeth.<br />

Diet: Beavers feed on the bark, cambium, twigs, leaves, and roots of deciduous<br />

trees and shrubs, such as willow, alder, birch, and aspen, and on various parts of<br />

aquatic plants, especially the young shoots of water lilies. Beavers anchor sticks and<br />

logs underwater to feed on during winter.<br />

Range: Alaska, Canada, conterminous United States, extreme northern Mexico.<br />

Habitat: Beavers are semiaquatic. They prefer streams and small lakes having<br />

nearby growths of willow, aspen, poplar, birch, or alder.<br />

Social Organization: Beavers are primarily nocturnal, but sometimes begin work in<br />

the afternoon. They are active throughout the year, but in the northern parts of<br />

their range during the winter they may leave their lodges only to travel to the nearby<br />

food cache. They may even remain lethargic and live off of stored body fat for a<br />

15

time. They do not hibernate. Beavers live in family groups consisting of an adult<br />

pair and the offspring of several years (they have one litter each year).<br />

They are often thought of as the “engineers” of the animal kingdom, because they<br />

build complex dams, lodges, and canals. A dam provides an area of still, deep water<br />

where a lodge can be conveniently constructed and protected from terrestrial<br />

predators, and in which building materials and food supplies can be easily floated and<br />

kept from being washed away. The foundation of a dam may consist of mud and<br />

stones. Then brush and poles are added, and mud, stones, and soggy vegetation are<br />

used as plaster on top of the poles. A dam is built higher than the water level. It<br />

may be kept in repair and extended over the years by several generations of<br />

beavers. The lodge is usually surrounded by the water backed up by the dam. The<br />

floor is above the water level and bedded with dry vegetation. Three are one or<br />

more underwater entrances that extend below the winter ice level. In some areas,<br />

especially the vicinity of large rivers, beavers do not build lodges, but dig dens in the<br />

banks for shelter.<br />

Sources: Knight, Linsay. The Sierra Club Book of Small Mammals. San Francisco:<br />

Weldon Owen Pty Limited, 1993. Page 60.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume I. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

493, 560-563.<br />

16

RED FOX<br />

(Vulpes vulpes)<br />

Carnivore<br />

Description: The fox is characterized by a rather long, low body; relatively short<br />

legs; a long, narrow muzzle; large, pointed ears; and a bushy, rounded tail that is at<br />

least half as long, and often fully as long, as the head and body. The typical<br />

coloration ranges from pale yellowish-red to deep reddish-brown on the upper parts,<br />

and is white, ashy, or slaty on the underparts. The lower part of the legs is usually<br />

black, and the tail is generally tipped with white or black.<br />

Teeth: The first incisor is the smallest and the third is the largest, the difference in<br />

size being most marked in the upper jaw. The canine teeth are pointed, elongate,<br />

and round to oval in section. The premolars are usually adapted for cutting, and the<br />

molars usually have four or more sharp, pointed cusps. The last upper premolar and<br />

the first lower molar are called the cartnassials, and often work together as a<br />

specialized shearing mechanism. The fox’s teeth stay hard and sharp because of a<br />

new layer of hard enamel that grows each year.<br />

Special Note: Have you ever counted the rings on a tree stump to see how old the<br />

tree was? In the same way, scientists can tell how old a fox is by looking at one of<br />

its teeth. If a fox’s tooth is cut in half, you can see a ring for each new layer of<br />

enamel. You can tell how old a fox is by counting the enamel rings on the tooth. By<br />

studying fox teeth in this way scientists have found that many foxes die from<br />

disease or are killed by predators when they are young. Those foxes that learn to<br />

hunt and defend themselves will often live to be 12 or older.<br />

Diet: While the fox is a carnivore, the diet can be considered omnivorous. It<br />

consists mostly of rodents, lagomorphs, insects, and sometimes fruit. To hunt mice,<br />

the red fox stands motionless, listens and watches intently, and then leaps suddenly,<br />

bringing its forelegs straight down to pin the prey. Rabbits are stalked and then<br />

captured with a rapid dash. The red fox will eat any animal it can catch or scavenge.<br />

This is one of the reasons it has survived so well. The fox likes rabbits, voles, mice<br />

and other small rodents best, but it will also eat insects, snails, eggs and other<br />

things that it finds on its travels. If a fox is lucky enough to kill a large animal, it<br />

may bury the part it does not eat right away and save it for a meal later on. If meat<br />

is scarce, foxes will also eat wild fruits such as blueberries and apples.<br />

Range: The red fox has settled in all areas of northern and central Europe, Asia, and<br />

northern America. The red fox continues to spread and it is pushing into the Arctic<br />

region, where it threatens to compete with the Arctic fox for food.<br />

17

Habitat: It is adaptable to all habitats - from lowland forests to town suburbs.<br />

Habitats range from deep forest to arctic tundra, open prairie, and farmland, but the<br />

red fox prefers areas of highly diverse vegetation and avoids large homogenous<br />

tracts.<br />

Social Organization: A home range is typically occupied by an adult male, one or two<br />

adult females, and their young. A female fox may sometimes mate with several<br />

males, but later she will establish a partnership with just one of them.<br />

Sources: Knight, Linsay. The Sierra Club Book of Small Mammals. San Francisco:<br />

Weldon Owen Pty Limited, 1993. Page 47.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

930, 932-933.<br />

Switzer, Merebeth. Red Fox. Danbury, CT: Grolier Educational Corporation, 1986.<br />

Pages 22, 29.<br />

18

RACCOON<br />

(Procyon lotor)<br />

Omnivore<br />

Description: The general coloration of the raccoon is gray to almost black,<br />

sometimes with a brown or red tinge. There are 5 to 10 black rings on the rather<br />

well-furred tail, and a black “bandit” mask across the face. They are good climbers<br />

and swimmers. Raccoons have a well-developed sense of touch, especially in the<br />

nose and forepaws. The hands are regularly used almost as skillfully as monkeys use<br />

theirs. Wild raccoons are most at home near water, and it spends much of its time in<br />

shallow water or mud near the water’s edge looking for something to eat. A<br />

raccoon’s sensitive, naked-soled feet and long toes, plus the short hair at its wrists,<br />

make this kind of food foraging easy.<br />

Teeth: Raccoons have three pairs of incisors and one pair of canines on both jaws.<br />

The number of premolars on the upper and lower jaws range from 3 to 4 pairs. On<br />

the upper jaw, there are two pairs of molars, while the lower jaw has 2 to 4 molars,<br />

for a total of 36 to 40 teeth. The last upper molar is relatively large and rounded.<br />

Diet: A raccoon is a true omnivorous animal. Its diet consists mainly of crayfish,<br />

crabs, other arthropods, frogs, fish, nuts, seeds, acorns, and berries. A raccoon will<br />

eat almost anything. Even garbage is high on its list of favorite foods. Raccoons<br />

living in the woods will check out camp sites and picnic places for any scraps of food<br />

that may have been left. Raccoons near farms, towns or cities visit any place where<br />

food may have been grown, cooked or stored. Trash piles, garbage cans, and pet<br />

food dishes are often raided. Exactly what a raccoon eats changes with the time of<br />

year and the area in which it lives. Raccoons tend to eat more plants than animals.<br />

They eat fruits, nuts, and grains. Acorns are their favorite nuts, but they will also<br />

eat hickory nuts, beech nuts, pecans and walnuts. Corn is by far their favorite grain.<br />

They like it best when it is in its “milk stage,” when it is green and before it has<br />

hardened. Raccoons eat wild berries of all kinds, whenever they can find them. At<br />

times, a raccoon may add grasses, weeds, seeds, and flower buds, to its diet.<br />

Raccoons favor invertebrates like crayfish, crabs, clams, and oysters that are found<br />

in mud or sand. When they can catch them, small animals such as squirrels, gophers,<br />

and mice are important food for raccoons. They will also eat turtles, turtle eggs,<br />

frogs, and fish. Because they like young chickens, turkeys and ducks, as well as<br />

eggs, raccoons can become quite expert at raiding farms and ranches. They also eat<br />

small birds, pheasants, and quail.<br />

Food is generally picked up with the hands and then placed in the mouth. Although<br />

raccoons have sometimes been observed to dip food in water, especially under<br />

captive conditions, the legend that they actually wash their food is without<br />

19

foundation. They often swish the foods back and forth in water to remove any sand<br />

and dirt. It may be this habit that gave the raccoon its name and its fame as a foodwasher.<br />

Raccoons also use their sense of touch to explore each piece of food they<br />

eat. They will turn the piece over and over with their “fingers,” and rub it between<br />

their forefeet. Scientists have learned that raccoons “feel” their food before eating<br />

it, more than they “wash” it.<br />

Range: Range is southern Canada to Panama.<br />

Habitat: Raccoons frequent timbered and brushy areas, usually near water.<br />

Social Organization: Raccoons are primarily solitary individuals, but they have been<br />

known to congregate in large numbers (up to 23!) in winter dens. They are more<br />

nocturnal than diurnal. A male and female may live together for a few weeks during<br />

the mating season. Then they go their separate ways. Three or four cubs are born<br />

in late spring, and will be nursed for three to four months. By early autumn, the<br />

cubs may spend several days and nights away from their mothers. Then they are off<br />

to find a home range of their own.<br />

Sources: Nentl, Jerolyn. The Raccoon. Mankato, MN: Crestwood House, 1984.<br />

Pages 19, 22-26.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

980-981.<br />

20

Appendix 4: CRC mammal species<br />

ARABIAN ORYX<br />

(Oryx leucoryx)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: Arabian oryxes have black and white face masks that recall the head<br />

markings of the gazelles. The arabian oryx is white, and has very dark brown, almost<br />

black, hair on its legs and face. The tail is tufted, and males have a tuft of hair on<br />

the throat. The ears are fairly short, broad, and rounded at the tips. Both sexes<br />

have horns that can be up to 4 feet long. Their horns are fairly straight and directed<br />

backward from the eyes.<br />

Teeth: The oryx has no upper incisors or canines. They do have three pairs of<br />

incisors and 0-1 pair of canines in the lower jaw. They have three pairs of premolars<br />

in the upper jaw and 2-3 pairs of premolars in the lower jaw. There are also three<br />

pairs of molars in both the upper and lower jaws. The total number of teeth is 30-<br />

32. The surfaces of their molars have a smooth texture.<br />

Diet: The oryx diet consists of grasses and herbs, juicy roots and fruits, melons,<br />

leaves, buds, and bulbs. They drink water when it is available, but they can go<br />

without water for several days.<br />

Range: Originally found in Syria, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Sinai, and the Arabian Peninsula.<br />

Habitat: Habitat consists of flat and undulating gravel plains intersected by shallow<br />

wadis and depressions, and the dunes edging sand deserts, with a diverse vegetation<br />

of trees, shrubs, herbs, and grasses.<br />

Social Organization: The normal group size is 10 animals or fewer, but herds of up<br />

to 100 have been reported. Groups are mostly females and young dominated by<br />

one adult male.<br />

Conservation Status: This species declined primarily because the expansion of the<br />

oil industry led to hunting from motor vehicles with modern firearms. Its meat is<br />

greatly esteemed, its hide is valued as leather, other parts have alleged medicinal<br />

uses, and the head makes a choice trophy. They were extinct in the wild until the<br />

success of recent reintroduction programs in Saudi Arabia and Jordan.<br />

Sources: Arabian Oryx Species Survival Plan Fact Sheet. Acting SSP Coordinator:<br />

Jerry Brown, Phoenix <strong>Zoo</strong>, 455 North Galvin Parkway, Phoenix, AZ 85008.<br />

21

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

1265-1266.<br />

Walther, Fritz Rudolf. “Roan and Sable Antelopes.” Grzimek’s Encyclopedia of<br />

Mammals. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing Co., 1990. Volume IV, pages 437-448.<br />

22

BACTRIAN CAMEL<br />

(Camelus bactrianus)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: The Bactrian, or two-humped, camel is characterized by a long, thin<br />

neck, a small head, and a slender snout with a cleft upper lip. The hind part of the<br />

body is contracted and they have a relatively short tail. The color varies from deep<br />

brown to dusty gray. These camels have long hairs that are thickest on the head,<br />

neck, humps, forelegs, and tip of the tail. The eyes have heavy lashes and the ears<br />

are small and haired. Their long, slender legs have prominent knee pads. Contrary to<br />

popular belief, camels do not “store” water in their humps, but they can go for very<br />

long periods without drinking.<br />

Teeth: Camels have one pair of incisors in the upper jaw and three pairs of incisors<br />

in the lower jaw. The incisors, which are spatulate, are located in the forward,<br />

somewhat upward position. The canines are nearly erect and pointed, and are<br />

sometimes absent in the lower jaw. The molars have crescentic ridges of enamel on<br />

their crowns. They have 2-3 pairs of premolars and three pairs of molars in both of<br />

the jaws. Thus, the total number of teeth is between 30-34.<br />

Diet: Camels are grazers, feeding on many kinds of grass, though, when hungry,<br />

they will eat a wide variety of food. They thrive on salty plants that are wholly<br />

rejected by other grazing mammals. If forced by hunger, they will eat fish, flesh,<br />

bones, and skin.<br />

Range: The bactrian camel was formerly found throughout the dry steppe and<br />

semidesert zone from Soviet Central Asia to Mongolia. Today it is found on the Gobi<br />

Steppe along rivers, but moves to the desert as soon as the snow melts.<br />

Habitat: Wild camels inhabit semiarid to arid plains, grasslands, and deserts.<br />

Social Organization: Camels are diurnal. They are found alone or in groups,<br />

sometimes with over 30 individuals. Camels usually bear a single offspring, rarely<br />

two. At 4 years, the young camel becomes wholly independent. Full growth is<br />

attained at 5 years. Potential longevity is 50 years.<br />

Conservation Status: Because of human population growth, there has been drastic<br />

reduction in the range of wild camels, but domesticated members of the family have<br />

spread over much of the world. In Central Asia, the Bactrian camel was<br />

domesticated as early as the third and fourth centuries B.C., and its range was<br />

extended from Asia Minor to northern China. Wild populations also remained<br />

common until the 1920’s, but subsequently became restricted to relatively small<br />

23

areas of southwestern Mongolia and northwestern China. About 300-500 individuals<br />

now survive in the wild.<br />

Sources: Gauthier-Pilters, H. and A. I. Dagg. The Camel. Chicago: The University of<br />

Chicago Press, 1981.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

1188- 1191, 1193-1195.<br />

24

BLACK-FOOTED FERRET<br />

(Mustela nigripes)<br />

Carnivore<br />

Description: The black-footed ferret is a small weasel-like animal with a black mask<br />

around its eyes and black legs and feet. It is between 43-56 cm long (18-22 in),<br />

including its tail. It weighs up to 1.2 kg (2.5 lbs). Black-footed ferrets live<br />

underground as much as possible in order to avoid their natural enemies which are<br />

hawks, bobcats, owls, badgers and coyotes.<br />

Teeth: Black-footed ferrets have three pairs of incisors in the upper jaw and 2-3<br />

pairs in the lower jaw. They have one pair of canines and 2-4 pairs of premolars in<br />

both jaws. In the upper jaw, there is one pair of molars and the lower jaw has 1-2<br />

pairs of molars. Thus, the total number of teeth ranges between 30-38 teeth. The<br />

upper molar is relatively large and squarish or dumbell-shaped.<br />

Diet: Prairie dogs, which are often equal or larger in size than the ferret, make up<br />

90% of its diet. It also eats rabbits and rodents on occasion.<br />

Range: The black-footed ferret formerly ranged from Mexico to Canada through the<br />

western plains states. It was thought to be extinct in the 1970’s, however, in 1981,<br />

a population was found in Meeteetse, Wyoming. In 1985, disease almost destroyed<br />

this small population, and in 1987, the survivors were removed to captivity.<br />

Through breeding programs in zoos, including the Conservation & Research Center,<br />

the species has been saved from extinction and is now being reintroduced back into<br />

the wild.<br />

Habitat: The black-footed ferret is found mainly on short and mid-grass prairies. It<br />

lives almost exclusively in prairie dog towns of the Great Plains. Prairie dog towns<br />

are a community network of prairie dog dens and tunnels that can cover hundreds of<br />

acres. Black-footed ferrets den in abandoned prairie dog burrows.<br />

Social Organization: Black-footed ferrets are primarily nocturnal, and they are<br />

thought to have keen senses of hearing, smell, and sight. They are thought to be<br />

solitary hunters and can use a range of around 100 acres each. A male ferret’s<br />

territory may overlap that of several females with which he mates. Females raise a<br />

litter of about three to four kits without help from males.<br />

Conservation Status: The decline of the black-footed ferret was almost entirely due<br />

to government-sponsored poisoning of prairie dog towns and the development of<br />

farms, roads, towns, etc. over prairie dog colonies. Seven zoos, including the<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Zoo</strong>’s Conservation & Research Center, participate in the Black-Footed<br />

25

Ferret Recovery Program. Under the direction of the Black-Footed Ferret Species<br />

Survival Plan, these institutions breed genetically valuable ferrets for reintroduction<br />

back into the wild. Four states currently have reintroduciton programs. The goal of<br />

the Black-Footed Ferret Recovery Program is to have 10 self-sustaining black-footed<br />

ferret populations in the wild by the year 2010.<br />

Sources: Black-footed Ferret Species Survival Plan Fact Sheet. rev. 5/94. SSP<br />

Coordinator: Astrid Vargas, DVM, PhD, <strong>National</strong> Black-Footed Ferret Conservation<br />

Center, 410 E. Grand Ave., Ste. 315, Laramie, WY 82070.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

993-994.<br />

26

BURMESE BROW-ANTLERED DEER<br />

(Cervus eldi thamin)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: The upper parts of the Burmese brow-antlered deer, or Eld’s deer, are<br />

some shade of brown, and the underparts are paler. The pelage (coat) is coarse, and<br />

most males have a long, dense mane. The antlers are “lyre shaped” after the<br />

ancient Greek instrument.<br />

Teeth: Deer species have no upper incisors and three pairs of lower incisors. They<br />

have 0-1 pair of canines in both jaws. They have three pairs of premolars and molars<br />

in both the upper and lower jaws, for a total of 32-34 teeth. The surfaces of their<br />

molars have a smooth texture.<br />

Diet: Eld’s deer are grazers, but browse on trees and shrubs opportunistically. They<br />

will supplement their diet with wild fruit and cultivated crops, particularly rice.<br />

Range: Once widespread in tropical areas throughout Indo-China, the Eld’s deer<br />

extended as far west as the State of Manipur in India. Today, it survives precariously<br />

in a few reserves.<br />

Habitat: They formerly inhabited monsoon forests composed mainly of tropical<br />

deciduous hardwoods with thin canopies and with grassy ground cover. They prefer<br />

open grasslands or savannas. Now they are confined to habitat fragments in<br />

Burmese deciduous forests with open understories.<br />

Social Organization: The males and females are separate for most of the year<br />

except during breeding season. Females herd into family groups with their young,<br />

and males are solitary.<br />

Conservation Status: There are said to be 2000-3000 Burmese Eld’s deer still living<br />

along the large rivers in Burma. Few mammalian genera have been so extensively<br />

affected by people. On one hand, various species of Cervus, including Eld’s deer,<br />

have been introduced to many areas beyond their natural range. There has also<br />

been much manipulation of herds in an effort to improve big game hunting. On the<br />

other hand, excessive hunting and habitat modification have resulted in drastic<br />

declines in the natural distribution and numbers of most species. The most seriously<br />

jeopardized populations are found mainly in the less-developed parts of the world.<br />

Problems vary, but generally involve uncontrolled hunting for food and commerce,<br />

and usurpation of habitat by the growing number of people.<br />

27

Sources: Kurt, Fred. “True Deer.” Grzimek’s Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York:<br />

McGraw Hill Publishing Co., 1990. Volume V, pages 174-175.<br />

Monfort, Steven L., Christen M. Wemmer, and William J. McShea. “Ecological<br />

Correlates of Reproductive Seasonality in the Eld’s deer (Cervus eldi thamin) in<br />

Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary, Myanmar.” 1997 Research Proposal.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

1209-1212.<br />

28

CLOUDED LEOPARD<br />

(Panthera nebulosa)<br />

Carnivore<br />

Description: The clouded leopard is frequently described as bridging the gap<br />

between big and small cats. It has very short legs and a long, bushy tail, and its coat<br />

is brown or yellowish-gray and covered with irregular dark spots and blotches<br />

resembling clouds. There are broad black bands on the face and large spots and<br />

broad bands on the neck and legs; the tail also bears broad, dark bands at regular<br />

intervals. It weighs 16 to 23 kg (35 to 50 lbs) and stands 25 to 41 cm (10 to 16<br />

inches) high at the shoulder. It is a skilled tree-climber, even descending the trunks<br />

with its head pointed downward. The skull is long, low, and narrow.<br />

Teeth: Clouded leopards, like other cat species, have three pairs of incisors and one<br />

pair of canines in both the upper and lower jaws. The upper canine teeth are the<br />

longest, relative to its size, than those of any other living cat. There are 2-3<br />

premolars in the upper jaw and two pairs in the lower jaw. The first upper premolar<br />

is greatly reduced or absent, leaving a wide gap between the canine and the molars.<br />

They have one pair of molars in both jaws, for a total of 28-30 teeth. Their last<br />

upper molar is small and round.<br />

Diet: The chief prey of the clouded leopard are monkeys, small deer, wild boars,<br />

cattle, young buffalo, goats, birds, and even porcupines which it ambushes from the<br />

trees or stalks from the ground. It may also take birds, rodents and domestic<br />

poultry. The leopard depends primarily on animals that live on the ground for food.<br />

Range: The clouded leopard lives in the evergreen rainforests at the foot of the<br />

Himalayas throughout Indo-China, and on Taiwan, Hainan, Sumatra, and Borneo.<br />

Habitat: Little is known about the clouded leopard in the wild. It was previously<br />

thought to be highly arboreal based on anecdotal observations. However, there is no<br />

field evidence to support this assumption. It now appears that trees are used<br />

primarily for resting sites, and clouded leopard movements are typically terrestrial. It<br />

prefers the deep forest far away from human habitation. It is known to Malaysians<br />

as the “tree tiger.”<br />

Social Organization: Because the clouded leopard is such a secretive forest animal,<br />

much of the knowledge of its social behavior comes from observations in zoological<br />

facilities. In captivity, they show a preference for monogamist pairings, which is very<br />

unusual in felines. Mating pairs are most successful when animals are introduced<br />

before their first year of age. After that time, introductions can be extremely<br />

29

dangerous because of aggression, and males will often injure or even kill females.<br />

The females bear two to four young, which reach independence in under one year.<br />

Conservation Status: The clouded leopard is a classic example of a species that is<br />

known to be rare and whose numbers, in spite of the ban on trade, are dwindling<br />

because in many parts of its range, the forests continue to be destroyed. Clear<br />

cutting of forests for use as agricultural lands is its primary threat, as the clouded<br />

leopard requires large tracts of forest for hunting. It has been poisoned as well,<br />

either as a livestock predator or for its coat, which is worth over $2,000 in the black<br />

market. Because it is extremely difficult to breed in captivity, the Conservation &<br />

Research Center is studying ways of using assisted reproduction (artificial<br />

insemination and in vitro fertilization) to breed clouded leopards.<br />

Sources: Clouded Leopard Species Survival Plan Fact Sheet. 2/91. SSP Coordinator:<br />

John Lewis - John Ball <strong>Zoo</strong>logical Gardens - 1300 W. Fulton Street - Grand Rapids, MI<br />

49504.<br />

Leyhausen, Paul. “Clouded leopard.” Grzimek’s Encyclopedia of Mammals. New<br />

York: McGraw Hill Publishing Co., 1990. Volume IV, pages 3-6.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Page<br />

1083.<br />

30

GOELDI’S MONKEY<br />

(Callimico goeldii)<br />

Omnivore<br />

Description: Adult goeldi’s monkeys are brownish black, with buffy markings on the<br />

back of the neck and two or three light buff-colored rings on the basal part of the<br />

tail. Head and body length is 21 to 23.5 cm (8.4 to 9.4 inches), tail length is 25.5<br />

to 32.5 cm (10.2 to 13 inches), and adult weight is 393 to 860 grams (13.8 to 30<br />

ounces).<br />

Teeth: The goeldi’s monkey has two pairs of incisors, one pair of canines, and three<br />

pairs of premolars and molars in both the upper and lower jaws. This amounts to 36<br />

teeth in total.<br />

Diet: Its diet includes fruit, insects, and some vertebrates.<br />

Range: This species occurs in the upper Amazonian rain forests of Columbia, eastern<br />

Ecuador, eastern Peru, western Brazil, and northern Bolivia.<br />

Habitat: It prefers deep, mature forests and is relatively rare in areas accessible to<br />

people. It is found most frequently in the understory and on the ground.<br />

Social Organization: They live in relatively small groups centered on a mated adult<br />

pair. Litter size is normally one, and within a few weeks of birth the father or an<br />

older sibling takes responsibility for carrying the young. Sexual maturity is attained<br />

at an age of 18 to 24 months.<br />

Conservation Status: It is an extremely endangered species, and its natural rarity<br />

makes it vulnerable to such adverse factors as habitat destruction and hunting.<br />

Source: Goeldi’s Monkey Species Survival Plan Fact Sheet. SSP Coordinator: Melinda<br />

Pruett-Jones, Brookfield <strong>Zoo</strong>, 3300 South Golf Road, Brookfield, IL 60513.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume I. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Page<br />

392.<br />

31

LONG-NOSED ARMADILLO<br />

(Dasypus novemcinctus)<br />

Specialized Carnivore (Insectivore)<br />

Description: The skin of the armadillo is remarkably modified to provide a doublelayered<br />

covering of horn and bone over most of the upper surface and sides of the<br />

animals, and some protection to the underparts and limbs. The covering consists of<br />

bands or plates, connected or surrounded by flexible skin. The long-nosed armadillo,<br />

often referred to as the 9-banded armadillo, actually usually has 8 bands in the<br />

northern and southern parts of its range, and 9 in the central part of the range. The<br />

top of the head has a shield, and the tail is usually encased by bony rings or plates.<br />

The body is mottled brownish and yellowish white.<br />

Teeth: The skull is flattened, and the lower jaw is elongate. Armadillos have no<br />

incisors or canines in either jaw. The teeth are small, peglike, ever growing, and<br />

numerous. They have between 7-25 cheek teeth, the premolars and molars are<br />

indistinguishable. The total number of teeth ranges from 28-100.<br />

Range: South-central and southeastern United States to Peru and northern<br />

Argentina, Grenada in the Lesser Antilles, Trinidad, and Tobago.<br />

Habitat: Long-nosed armadillos are partial to dense shady cover and limestone<br />

formations, from sea level to 3,000 meters elevation.<br />

Diet: They feed on mostly on insects (beetles and ants) and other invertebrates.<br />

Social Organization: They travel singly, in pairs, or occasionally in small bands. They<br />

are terrestrial in habit, powerful diggers and scratchers, and mainly nocturnal. When<br />

not active they usually live in underground burrows. Armadillos generally give birth<br />

to several identical young produced from a single ovum. The young are covered with<br />

a soft, leathery skin, which gradually hardens with age.<br />

Sources: Lavies, Bianca. It’s an Armadillo! New York: E. P. Dutton, 1989.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume I. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

460-461, 466-467.<br />

32

MANED WOLF<br />

(Chrysocyon brachyurus)<br />

Carnivore<br />

Description: The maned wolf is an unusual looking animal with extremely long legs,<br />

large ears and long pointed face. It is known affectionately to some people as the<br />

“fox on stilts.” It is larger than a coyote, standing three feet tall at the shoulder and<br />

weighing approximately 23 kg (50 lbs). It has golden-red fur, black legs and a black<br />

mane on the back of its neck and shoulders. It is thought that its long legs allow it<br />

to travel and see better in tall grasslands. It often walks with an unusual pacing gait,<br />

where the pairs of legs on each side of its body move together instead of<br />

alternately. The long legs are an adaptation to the tall grass; maned wolves are<br />

amblers, which is quite unusual for predatory animals.<br />

Teeth: Canids have three pairs of incisors in both upper and lower jaws, for a total<br />

of twelve. They have one pair of canines and four pairs of premolars in both jaws. In<br />

the upper jaw, the number of molars range from 1-4, while the lower jaw has<br />

anywhere between 2-5 pairs. Their last upper molar is relatively large and<br />

transversely elongate.<br />

Diet: Interestingly, while the maned wolf is a carnivore, the main items in its diet are<br />

fruits, particularly lobeira, a small tomato-like berry, along with a more “usual”<br />

carnivore diet of small mammals such as rodents and rabbits, and insects. When<br />

food is readily available, the maned wolf stores it away; it digs a hole with the<br />

forepaws, places the food in it, and closes the hole with its snout.<br />

Range: The maned wolf is found in South American grasslands and scrub forest of<br />

Brazil, northern Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia.<br />

Habitat: Maned wolf habitat is the grassy steppe, arid bush forest, wet wooded<br />

islands, dried river beds, and swampy areas.<br />

Social Organization: Maned wolves are solitary animals most of the year. A male<br />

and female pair share the same territory, but interact mainly during the breeding<br />

season. The female bears two to four pups, which the male may help rear. They<br />

have no natural enemies, but it is afflicted with a number of parasites. The maned<br />

wolf is active at dusk and at night. However, in areas that are untouched by human<br />

activity, they are also active during the day.<br />

Conservation Status: The maned wolf has almost no natural enemies, but<br />

nevertheless is in great danger because it needs wide, uninterrupted spaces. With<br />

33

its habits and striking appearance, it is not suited to follow the development of<br />

civilization.<br />

Sources: Maned Wolf Species Survival Plan Fact Sheet. rev. 5/94. SSP Coordinator:<br />

Melissa Rodden, NZP Conservation & Research Center, 1500 Remount Road, Front<br />

Royal, VA 22630.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

957-958.<br />

34

MATSCHIE’S TREE KANGAROO<br />

(Dendrolagus matschiei)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: Tree kangaroos are marsupials, and are the only members of the<br />

kangaroo family which live in the trees. Matschie’s tree kangaroos range in size from<br />

6.8-18 kg (15 to 40 lbs). Despite their life in the trees, these animals lack the<br />

opposable thumb or prehensile tail of opossums. They differ from terrestrial<br />

kangaroos in having shorter, wider hind feet and a long, narrow tail that is used for<br />

balance. All four feet have heavy, curved claws that aid in climbing. It is among the<br />

most brilliantly colored of marsupials; its back is red or mahogany brown, its face,<br />

belly, and feet are bright yellow, and its tail is mostly yellow. The long, well-furred<br />

tail is of nearly uniform thickness and acts as a balance; it is not prehensile, but is<br />

often used to brace the animal when climbing.<br />

Teeth: The kangaroo family, Macropodidae, is characterized by three pairs of<br />

incisors in the upper jaw and one pair of incisors in the lower. The number of canines<br />

in the upper jaw range from 0-1, while the lower jaw contains no canines. Tree<br />

kangaroos have two pairs of premolars and four pairs of molars in both upper and<br />

lower jaws. This makes a total of 32-34 teeth. The upper and lower incisors are<br />

large and sometimes grow horizontally. The upper canine, if present, is relatively<br />

small.<br />

Diet: Tree kangaroos feed primarily on tree leaves, but also eat flowers, grass and<br />

fruit, which are digested in their sacculated stomachs by fermenting bacteria.<br />

Range: Tree kangaroos are found only on the island of New Guinea and in<br />

northeastern Australia.<br />

Habitat: Dense tropical forests from sea level to nearly 3000 meters (10,000 ft) in<br />

altitude are home to the tree kangaroo. These animals live in extremely inhospitable<br />

and inaccessible mountain forests.<br />

Social Organization: Little is known about the tree kangaroo in the wild. Most<br />

species of tree kangaroo appear to be solitary. It appears that females keep a<br />

territory of a few acres, while males have larger territories which overlap those of<br />

several females. The female has a single joey which, like those of other marsupials,<br />

is born small and quite undeveloped. It climbs unassisted into the pouch where it will<br />

stay for approximately 10 months. Joeys continue to nurse for several months after<br />

permanently leaving the pouch.<br />

35

History: Tree kangaroos are especially interesting to zoologists because of their<br />

unique history. They are a living model for the total reversal of a direction of<br />

specialization, the gradual adaptations of which are evident in a number of species.<br />

Both zoologists and the general public find it extraordinary that a family of lightfooted,<br />

jumping animals living mainly in such habitats as scrub, plains, and rocky<br />

terrain should include several arboreal species. Finally, they seem poorly equipped<br />

for this habitat. The tree kangaroo is not able to “hop” like the ground dwelling<br />

kangaroos. Rather, it usually takes little hopping steps, in which the two forelegs<br />

and the two hind legs alternately touch the ground.<br />

It seems likely that tree kangaroos returned to the arboreal lifestyle because of their<br />

primitive browsing ancestors’ quest of succulent leafy sustenance.<br />

Conservation Status: Tree kangaroos are primarily threatened by hunting for meat<br />

and habitat destruction from logging, mining, oil exploration and agriculture.<br />

Sources: Collins, Larry R. “Big Foot of the Branches.” <strong>Zoo</strong>goer. July-August 1986,<br />

pages 15-18.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume I. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

88-89.<br />

Tree Kangaroo Species Survival Plan Fact Sheet. rev. 5/94. SSP Coordinator: Valerie<br />

Thompson, San Diego <strong>Zoo</strong>, PO Box 551, San Diego, CA 92112.<br />

36

PERE DAVID’S DEER<br />

(Elaphurus davidianus)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: The most unusual thing about Pere David’s deer is the stags’ antlers,<br />

which are reminiscent of giant roots. While two knobby antler beams rise vertically<br />

out of the frontal bone, they sprout very bizarrely shaped side branches - not<br />

forward, but rather toward the rear. The summer pelage, reddish tawny and mixed<br />

with gray, is much shorter than the grayish buff winter pelage. A mane is present on<br />

the neck and throat.<br />

Teeth: Deer species have no upper incisors and three pairs of lower incisors. They<br />

have 0-1 pair of canines in both jaws. They have three pairs of premolars and molars<br />

in both the upper and lower jaws, for a total of 32-34 teeth. The surfaces of their<br />

molars have a smooth texture.<br />

Diet: Although it supplements its grass diet with water plants in the summer, it is<br />

essentially a grazing animal.<br />

Range: It formerly inhabited the broad, swampy plains of the large river valleys of<br />

China. It is now extinct in the wild.<br />

Habitat: Pere David’s deer may have originally inhabited swampy, reed-covered<br />

marshlands.<br />

Social Organization: Females are clustered into “hinds,” or large groups. Adult<br />

males keep to themselves for about 2 months before and 2 months after the mating<br />

season. When the mating season begins, a stag joins with a group of females (now<br />

his harem) and fights off all other males. After all the females have come into heat<br />

and been impregnated by the stag, he leaves the harem to feed.<br />

History and Conservation Status: These animals liked to browse in open spaces,<br />

thus making them more easily hunted and their population was reduced early on.<br />

Only thanks to the avid collecting of a powerful, animal-loving Emperor of China was<br />

a herd captured and installed in the imperial park of Nan Hai-tsu south of Peking.<br />

This, at least, preserved the species in captivity. In the wild, though, its eradication<br />

continued until, in 1939, the last known Pere David’s deer living in the wild was shot<br />

not far from the Yellow Sea.<br />

It was a mere historic coincidence that led to the discovery and thus eventual rescue<br />

of the Pere David’s deer. A Jesuit priest, Armand David, negotiated with the<br />

Emperor and obtained permission to import several pairs to European zoos.<br />

37

Subsequently, the emperor’s game park in China was destroyed by floods and the<br />

deer that were held there were killed. The Duke of Bedford, in his spacious game<br />

park in England, recognized that the species was at risk of complete extinction. He<br />

took care to provide a well thought-out breeding program for increasing the<br />

population. It succeeded beyond all expectations. Preservation of the Pere David’s<br />

deer is considered to this day an exemplary instance of zoologically-based animal<br />

conservation though planned breeding in captivity.<br />

Sources: Butzler, Wilfried. “Pere David’s Deer.” Grzimek’s Encyclopedia of Mammals.<br />

New York: McGraw Hill Publishing Co., 1990. Volume V, pages 161-164.<br />

Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 4th<br />

edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Pages<br />

1212-1213.<br />

38

PERSIAN ONAGER<br />

(Equus hemionus onager)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: The onager, or wild ass, has a general body form that is thick headed,<br />

short legged, and stocky. They are tawny colored. The tail is moderately long, with<br />

the hairs reaching at least to the middle of the leg when the tail is hanging down.<br />

Their bodies are heavily haired with a mane on the neck and a lock of hair on their<br />

forehead, known as the forelock.<br />

Teeth: The onager has three pairs of incisors and 0-1 pair of canines in both the<br />

upper and lower jaws. The incisors are shaped like chisels, the enamel on the tips<br />

folding inward to form a pit, or “mark,” that is worn off in early life. The cheek teeth<br />

have a complex structure. They are high crowned, with four main columns and<br />

various infoldings with much cement. They have 3-4 pairs of premolars in the upper<br />

jaw and three pairs of premolars in the lower jaw. They also have three pairs of<br />

molars in both jaws, for a total of 36-42 teeth.<br />

Diet: Onagers are entirely vegetarian in habit, feeding mainly on grass, although<br />

some browsing in the low branches of trees and shrubs is done. They drink water<br />

daily; however, onagers can go for longer periods without water than can any other<br />

species of equid, and they are remarkably capable of surviving on a minimum of food<br />

and under hot and difficult conditions.<br />

Range: They are located in the desert and dry steppe zone from Syria and Iraq to<br />

Manchuria and western India.<br />

Habitat: The onager is found mostly in desert plains, sparsely covered with low<br />

shrub.<br />

Social Organization: Members of this species live in unstable groups of variable<br />

composition, and there is no indication of permanent bonds between any adult<br />

individuals.<br />

Conservation Status: The wild asses of Asia have declined drastically though such<br />

factors as excessive hunting, habitat deterioration, transmission of disease from<br />

livestock, and interbreeding with the domestic donkey.<br />

Source: Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World.<br />

4th edition, Volume II. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.<br />

Pages 1157-1163.<br />

39

PRZEWALSKI’S HORSE<br />

(Equus ferus przewalskii)<br />

Herbivore<br />

Description: The Przewalski’s horse, also known as the Asian or Mongolian wild<br />

horse, is the only true wild horse that exists today. It is small and sturdy with a<br />

sandy-colored coat and a short stiff mane. It has a thick neck and heavy head, and<br />

dark legs often with faint striping and a dark stripe down the back. In Mongolia, the<br />

wild horse is known as “takhi” which means “spirit” or “spiritual” in Mongolian. The<br />

species is a symbol of the Mongolian national heritage.<br />

Teeth: The Przewalski’s horse has three pairs of incisors and 0-1 pair of canines in<br />

both the upper and lower jaws. The incisors are shaped like chisels, the enamel on<br />

the tips folding inward to form a pit, or “mark,” that is worn off in early life. The<br />

cheek teeth have a complex structure. They are high crowned, with four main<br />

columns and various infoldings with much cement. They have 3-4 pairs of premolars<br />

in the upper jaw and three pairs of premolars in the lower jaw. They also have three<br />

pairs of molars in both jaws, for a total of 36-42 teeth.<br />

Diet: Grasses make up the diet of the Przewalski’s horse.<br />

Range: Though they are thought to be extinct in the wild, Przewalski’s horses<br />

formerly ranged over Mongolia, China, and the Soviet Union. They were last seen in<br />

the wild during the 1960s in the Gobi, which accounts for roughly the southern third<br />

of Mongolia.<br />

Habitat: Grassy plains and steppes of central Asia make up its habitat. It requires<br />

access to drinking water.<br />

Social Organization: The herd structure of the Przewalski’s horse is highly<br />

developed, with a dominant stallion defending his group. Young males are ejected<br />

from the herd prior to their reaching sexual maturity. A hierarchy exists among the<br />

females of the herd and a lead mare often guides the herd in grazing activities.<br />

Conservation Status: The Przewalski’s horse was driven into extinction in the wild by<br />

hunting and encroachment of domestic animals grazing in their habitat. The horses<br />

were forced further back in the desert where they had difficulty finding adequate<br />

water. However, zoos saved the wild horse from dying out altogether by breeding<br />

the species. All of the approximately 1,200 wild horses alive today are descended<br />

from 12 that were caught in the wild around 1900.<br />

40

Today’s Przewalski’s horse population enjoys remarkably good genetic health. The<br />