Transplanting Pink lady-slipper (Cypripedium acaule) - William Cullina

Transplanting Pink lady-slipper (Cypripedium acaule) - William Cullina

Transplanting Pink lady-slipper (Cypripedium acaule) - William Cullina

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Transplanting</strong> <strong>Pink</strong> <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>s (<strong>Cypripedium</strong> <strong>acaule</strong>)<br />

Images and text by <strong>William</strong> <strong>Cullina</strong><br />

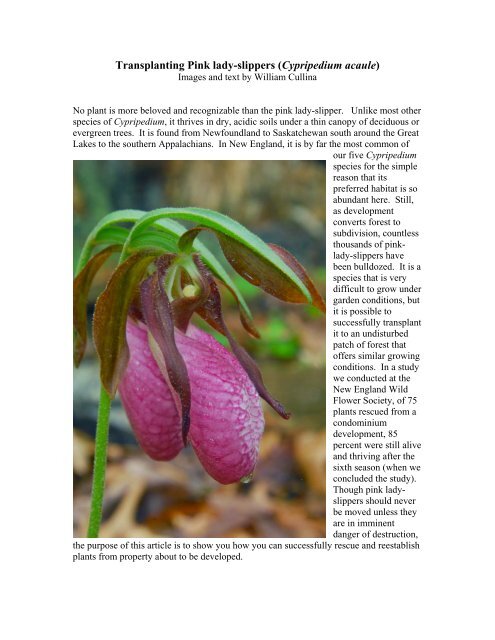

No plant is more beloved and recognizable than the pink <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>. Unlike most other<br />

species of <strong>Cypripedium</strong>, it thrives in dry, acidic soils under a thin canopy of deciduous or<br />

evergreen trees. It is found from Newfoundland to Saskatchewan south around the Great<br />

Lakes to the southern Appalachians. In New England, it is by far the most common of<br />

our five <strong>Cypripedium</strong><br />

species for the simple<br />

reason that its<br />

preferred habitat is so<br />

abundant here. Still,<br />

as development<br />

converts forest to<br />

subdivision, countless<br />

thousands of pink<strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>s<br />

have<br />

been bulldozed. It is a<br />

species that is very<br />

difficult to grow under<br />

garden conditions, but<br />

it is possible to<br />

successfully transplant<br />

it to an undisturbed<br />

patch of forest that<br />

offers similar growing<br />

conditions. In a study<br />

we conducted at the<br />

New England Wild<br />

Flower Society, of 75<br />

plants rescued from a<br />

condominium<br />

development, 85<br />

percent were still alive<br />

and thriving after the<br />

sixth season (when we<br />

concluded the study).<br />

Though pink <strong>lady</strong><strong>slipper</strong>s<br />

should never<br />

be moved unless they<br />

are in imminent<br />

danger of destruction,<br />

the purpose of this article is to show you how you can successfully rescue and reestablish<br />

plants from property about to be developed.

It is well known that all orchids have evolved a very sophisticated strategy for seed<br />

germination. Orchid seeds are tiny and lack well developed embryos. To germinate, the<br />

seed must come in contact with a<br />

specific soil fungus which<br />

surrounds the seed as if to digest it.<br />

The fungal roots (hyphae)<br />

penetrate the seed and then the<br />

orchid turns the tide, digesting the<br />

fungus instead. It seems that the<br />

fungus gets nothing from this<br />

arrangement except to be eaten, so<br />

rather than the symbiotic<br />

relationship found with most<br />

mychorrizal interactions, in this<br />

case the union is more properly<br />

called micoparisitism. After 3-4<br />

years in the soil growing larger at<br />

the expense of the fungus, the seeding emerges and begins to photosynthesize for its<br />

food. At this point, it is unclear how important the<br />

fungus becomes to the more mature <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>.<br />

Mature plants can remain underground for several<br />

years after a bad drought, predation, or other<br />

trauma, so it does appear that some continued<br />

relationship is important to the health of the plant.<br />

One plant that I moved in 1990 grew for a few<br />

years then disappeared, only to appear and bloom<br />

again in 2005 then disappear in 2006 and reappear<br />

in 2007 as a two-leaved but non-flowering plant!<br />

Just how widespread the proper group of fungi is<br />

through the range of the orchid is unclear, but<br />

absence of plants in apparently suitable habitat<br />

does not necessarily mean there is no fungus<br />

present. The most important consideration when<br />

choosing a spot for relocation is the pH of the soil,<br />

the available light, and potential competition from<br />

other plants. The pH of the soil is important<br />

because unless the soil is extremely acidic, C. <strong>acaule</strong> is prone to attack by root diseases<br />

that are naturally suppressed at low pH. Soils with a pH below 5.0 are optimal. You can<br />

test the soil with inexpensive pH test kits or look for indicator plants that like a similar<br />

habitat (obviously, if pink <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>s grow there already, it is ideal). In our area of<br />

southern New England as well as most parts of Central and Northern New England, the<br />

soils are considered to be very acidic. Pines, oaks, hickories, spruce, fir, and paper birch<br />

are common canopy species in pink <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong> habitat. Some indicator plants to for at<br />

ground level include:

Dendrolycopodium dendroideum Chimaphila maculata Gautheria procumbens<br />

(and other clubmosses) (spotted wintergreen) (wintergreen, checkerberry)<br />

Vaccinium angustifolium Gaylussacia baccata Kalmia angustifolia<br />

(lowbush blueberry and (black huckleberry) (sheep laurel)<br />

other blueberries)<br />

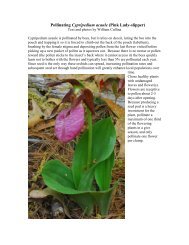

<strong>Pink</strong> <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>s do poorly in deep shade, and this is the most common reason they<br />

disappear over time from a given woods. They are most abundant in either very old<br />

forests with a mixed and broken canopy or in young forest regenerating after logging or<br />

fire. Road cuts and other edge habitats are also good places to find them. I look for<br />

places where the tree canopy has some gaps from windfalls or timber harvest to site

plants rather than in total shade under a continuous canopy.<br />

This is especially important under evergreens. Look for places where the sun breaks<br />

through for an hour or so each day.<br />

Chose areas where the ground is reasonably free of competition. Here huckleberries,<br />

wintergreen, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) and a small white pine indicate good<br />

habitat. I will site the plant just in front of the dead branch in the center.

Though in an emergency, you can successfully move pink <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>s at any time<br />

during the growing season, I have had the best results when I moved them in late summer<br />

just as the leaves begin to yellow. This plant flowered earlier in the season, but deer<br />

nipped of the bloom stalk. C. <strong>acaule</strong>’s roots are very shallow and spread out from the<br />

crown 8-24 inches in all directions, so care must be taken to damage them as little as<br />

possible.<br />

I use a pitchfork to lift the roots gently, coming in<br />

at a shallow angle about 12 inches from the crown<br />

and rocking the fork until the crown lifts up. At<br />

this point I use my hands to help tease the roots free from tree roots and debris. Here the<br />

plant has been lifted with little breakage of the roots and with some humus still<br />

surrounding them.

You can also<br />

remove plants<br />

bare-root as<br />

long as you have<br />

damp burlap to<br />

cover them with<br />

until them are<br />

replanted. This<br />

smaller<br />

individual<br />

has<br />

one welldeveloped<br />

bud<br />

visible in the<br />

center of the<br />

image and a<br />

moderately<br />

sized root<br />

system.<br />

Blackened roots<br />

are stained by humic acids in the soil but still healthy. The white roots are younger.<br />

Lady-<strong>slipper</strong><br />

roots will<br />

continue to live<br />

and grow longer<br />

over the course<br />

of about 5 years.<br />

However, if the<br />

growing tip is<br />

damaged on a<br />

particular root, it<br />

cannot grow<br />

another. In this<br />

image, the<br />

healthy white<br />

root began<br />

growing this<br />

spring (after<br />

flowering) as<br />

did the slightly<br />

more stained<br />

one at the left. Notice that this second root has lost its tip and can grow no<br />

longer.<br />

The<br />

roots are all important to <strong>lady</strong>-<strong>slipper</strong>s as they not only take up water and nutrients<br />

(and perhaps carbohydrates from the fungus) but they also act as the primary foodstorage<br />

organ for the plant during dormancy. If roots are cut or damaged during

transplant, they will stop growing and be vulnerable to infection. The loss of more than a<br />

few can spell disaster for the plant, as it has lost a good share of its food reserves and will<br />

likely wither away over the next year or two. This is a common occurrence in gardens,<br />

where a rescued or wild-collected plant will come up the first year, come back smaller the<br />

next, and fail to return the third. C. <strong>acaule</strong>’s roots inhabit what is called the F horizon in<br />

the soil. This<br />

is the zone or<br />

layer just<br />

underneath the<br />

unrotted leaves<br />

and other<br />

debris in this<br />

image. A few<br />

roots may pass<br />

through the<br />

narrow H<br />

horizon and<br />

into the black<br />

and gray A<br />

horizon. The<br />

H horizon is<br />

not topsoil, but<br />

rather a porous<br />

blend of<br />

partially<br />

decomposed<br />

organic<br />

materials.<br />

When<br />

replanting the<br />

orchid, it is<br />

essential that<br />

you relocate<br />

the roots in<br />

this layer as<br />

they will<br />

often<br />

rot if buried in<br />

the heavier<br />

horizons<br />

beneath.

I use a digging spade to scrape away the H horizon,<br />

exposing but no removing the lighter A horizon beneath.

Set the plant into this shallow hole and use your fingers to pack the duffy humus<br />

(H horizon) you just scraped off<br />

around the root mass (if the plant is<br />

bare-root, be extra careful to work the<br />

material in, around and between the<br />

roots so as they are spread out).

In this image, a bare-root plant has been set at the proper depth and is ready to be<br />

repacked with duff.<br />

Set the plant so that the tip of the white, pointed bud evident in this image lies just below<br />

the surface when you are finished.

The finished plant with<br />

unrotted leaves spread<br />

back over the roots once<br />

they have been backfilled<br />

with duff. By choosing a<br />

suitable spot, disturbing<br />

the soil horizons as little<br />

as possible and locating<br />

the roots at the proper<br />

depth, I have maximized<br />

this plant’s chances for<br />

success. Other than a<br />

good watering or two to<br />

settle the soil, no<br />

additional water or<br />

supplements are needed.<br />

The same plant the following spring with healthy leaves but no flowers. They are stiff<br />

and just pale enough to let me know they are receiving enough light.

Again, the same plant in its second spring, now with two growths and a beautiful bloom –<br />

both signs that it is settled in and thriving! Notice how the wintergreen in the first picture<br />

has spread beyond the dead branch and around the plant as it heads toward the light.<br />

Good Luck!<br />

©<br />

2007 <strong>William</strong> <strong>Cullina</strong>