Creating a Culture of Security

Creating a Culture of Security

Creating a Culture of Security

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

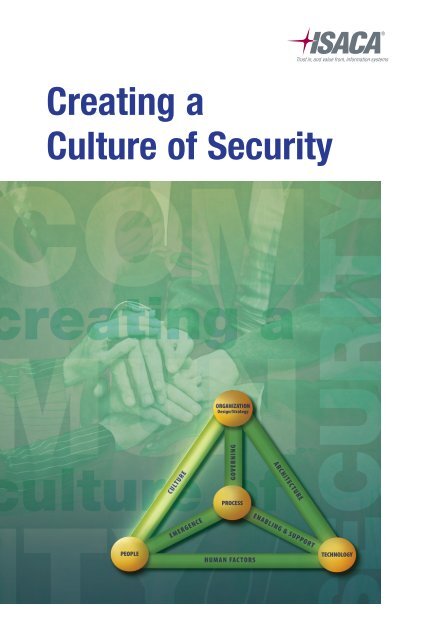

<strong>Creating</strong> a<br />

<strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong>

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

ISACA ®<br />

With 95,000 constituents in 160 countries, ISACA (www.isaca.org) is a leading global provider<br />

<strong>of</strong> knowledge, certifications, community, advocacy and education on information systems (IS)<br />

assurance and security, enterprise governance and management <strong>of</strong> IT, and IT-related risk and<br />

compliance. Founded in 1969, the nonpr<strong>of</strong>it, independent ISACA hosts international conferences,<br />

publishes the ISACA ® Journal, and develops international IS auditing and control standards,<br />

which help its constituents ensure trust in, and value from, information systems. It also advances<br />

and attests IT skills and knowledge through the globally respected Certified Information Systems<br />

Auditor ® (CISA ® ), Certified Information <strong>Security</strong> Manager ® (CISM ® ), Certified in the Governance<br />

<strong>of</strong> Enterprise IT ® (CGEIT ® ) and Certified in Risk and Information Systems Control TM (CRISC TM )<br />

designations. ISACA continually updates COBIT ® , which helps IT pr<strong>of</strong>essionals and enterprise<br />

leaders fulfill their IT governance and management responsibilities, particularly in the areas <strong>of</strong><br />

assurance, security, risk and control, and deliver value to the business.<br />

Disclaimer<br />

ISACA has designed and created <strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> (the “Work”) primarily as an<br />

educational resource for security pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. ISACA makes no claim that use <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Work will assure a successful outcome. The Work should not be considered inclusive <strong>of</strong> any<br />

proper information, procedures and tests or exclusive <strong>of</strong> other information, procedures and tests<br />

that are reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. In determining the propriety <strong>of</strong> any<br />

specific information, procedure or test, security pr<strong>of</strong>essionals should apply their own pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

judgment to the specific circumstances presented by the particular systems or information<br />

technology environment.<br />

Reservation <strong>of</strong> Rights<br />

© 2011 ISACA. All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be used, copied, reproduced,<br />

modified, distributed, displayed, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any<br />

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written<br />

authorization <strong>of</strong> ISACA. Reproduction and use <strong>of</strong> all or portions <strong>of</strong> this publication are permitted<br />

solely for academic, internal and noncommercial use and for consulting/advisory engagements and<br />

must include full attribution <strong>of</strong> the material’s source. No other right or permission is granted with<br />

respect to this work.<br />

ISACA<br />

3701 Algonquin Road, Suite 1010<br />

Rolling Meadows, IL 60008 USA<br />

Phone: +1.847.253.1545<br />

Fax: +1.847.253.1443<br />

E-mail: info@isaca.org<br />

Web site: www.isaca.org<br />

ISBN 978-1-60420-183-3<br />

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong><br />

CRISC is a trademark/service mark <strong>of</strong> ISACA. The mark has been applied for or registered in<br />

countries throughout the world.<br />

2<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

ISACA wishes to recognize:<br />

ACknowledgmentS<br />

aCknowledgementS<br />

Development Team<br />

Steven J. Ross, CISA, CBCP, CISSP, Risk Masters, Inc., USA, Author<br />

Jo Stewart-Rattray, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, CSEPS, RSM Bird Cameron, Australia, Chair<br />

Christos Dimitriadis, Ph.D., CISA, CISM, INTRALOT S.A., Greece<br />

Wendy Goucher, Idrach Ltd., UK<br />

Norman Kromberg, CISA, CGEIT, Alliance Data, USA<br />

Finn Olav Sveen, Ph.D., Gjøvik University College, Norway<br />

Vernon Poole, CISM, CGEIT, Sapphire, UK<br />

Rinki Sethi, CISA, eBay, USA<br />

Expert Reviewers<br />

Sanjay Bahl, CISM, Micros<strong>of</strong>t Corp. (India) Pvt. Ltd., India<br />

Garry Barnes, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, Commonwealth Bank <strong>of</strong> Australia, Australia<br />

Krag Brotby, CISM, CGEIT, NextStepInfoSec, USA<br />

Meenu Gupta, CISA, CISM, CBP, CIPP, CISSP, Mittal Technologies, USA<br />

Mark Lobel, CISA, CISM, CISSP, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, USA<br />

Naiden Nedelchev, CISM, CGEIT, Mobiltel EAD, Bulgaria<br />

Ramesan Ramani, CISM, CGEIT, Paramount Computer Systems, UAE<br />

Christophe Veltsos, Ph.D., CISA, CIPP, CISSP, GCFA, Minnesota State University, Mankato, USA<br />

ISACA Board <strong>of</strong> Directors<br />

Emil D’Angelo, CISA, CISM, Bank <strong>of</strong> Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd., USA, International President<br />

Christos K. Dimitriadis, Ph.D., CISA, CISM, INTRALOT S.A., Greece, Vice President<br />

Ria Lucas, CISA, CGEIT, Telstra Corp. Ltd., Australia, Vice President<br />

Hitoshi Ota, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, CIA, Mizuho Corporate Bank Ltd., Japan, Vice President<br />

Jose Angel Pena Ibarra, CGEIT, Alintec S.A., Mexico, Vice President<br />

Robert E. Stroud, CGEIT, CA Technologies, USA, Vice President<br />

Kenneth L. Vander Wal, CISA, CPA, Ernst & Young LLP (retired), USA, Vice President<br />

Rolf M. von Roessing, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, Forfa AG, Germany, Vice President<br />

Lynn C. Lawton, CISA, FBCS CITP, FCA, FIIA, KPMG Ltd., Russian Federation,<br />

Past International President<br />

Everett C. Johnson Jr., CPA, Deloitte & Touche LLP (retired), USA, Past International President<br />

Gregory T. Grocholski, CISA, The Dow Chemical Co., USA, Director<br />

Tony Hayes, CGEIT, AFCHSE, CHE, FACS, FCPA, FIIA, Queensland Government,<br />

Australia, Director<br />

Howard Nicholson, CISA, CGEIT, CRISC, City <strong>of</strong> Salisbury, Australia, Director<br />

Jeff Spivey, CPP, PSP, <strong>Security</strong> Risk Management, USA, ITGI Trustee<br />

Guidance and Practices Committee<br />

Kenneth L. Vander Wal, CISA, CPA, Ernst & Young LLP (retired), USA, Chair<br />

Kamal N. Dave, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, Hewlett-Packard, USA<br />

Urs Fischer, CISA, CRISC, CIA, CPA (Swiss), Switzerland<br />

Ramses Gallego, CISM, CGEIT, CISSP, Entel IT Consulting, Spain<br />

Phillip J. Lageschulte, CGEIT, CPA, KPMG LLP, USA<br />

Ravi Muthukrishnan, CISA, CISM, FCA, ISCA, Capco IT Service India Pvt. Ltd., India<br />

Anthony P. Noble, CISA, CCP, Viacom Inc., USA<br />

Salomon Rico, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, Deloitte, Mexico<br />

Frank Van Der Zwaag, CISA, Westpac New Zealand, New Zealand<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .<br />

3

4<br />

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

ACknowledgmentS (cont.)<br />

ISACA and IT Governance Institute ® (ITGI ® ) Affiliates and Sponsors<br />

American Institute <strong>of</strong> Certified Public Accountants<br />

ASIS International<br />

The Center for Internet <strong>Security</strong><br />

Commonwealth Association for Corporate Governance Inc.<br />

FIDA Inform<br />

Information <strong>Security</strong> Forum<br />

Information Systems <strong>Security</strong> Association<br />

Institut de la Gouvernance des Systèmes d’Information<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Management Accountants Inc.<br />

ISACA chapters<br />

ITGI Japan<br />

Norwich University<br />

Solvay Brussels School <strong>of</strong> Economics and Management<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Antwerp Management School<br />

ASI System Integration<br />

Hewlett-Packard<br />

IBM<br />

SOAProjects Inc.<br />

Symantec Corp.<br />

TruArx Inc.<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

ContentS<br />

table <strong>of</strong> ContentS<br />

Preface .............................................................................................................................. 9<br />

Endnotes ...................................................................................................................... 9<br />

1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11<br />

1.1 Hard and S<strong>of</strong>t <strong>Security</strong> ...................................................................................... 13<br />

1.2 Whose <strong>Culture</strong> Is It? ............................................................................................ 15<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................... 15<br />

2.0 A <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> in Context ........................................................................ 17<br />

2.1 Doing vs. Believing ........................................................................................... 17<br />

2.1.1 Ambiguity and Inconsistency.................................................................. 18<br />

2.2 <strong>Culture</strong> in Context ............................................................................................. 18<br />

2.2.1 Societal <strong>Culture</strong> and <strong>Security</strong> ................................................................ 20<br />

2.2.2 Organizational <strong>Culture</strong> and <strong>Security</strong> ...................................................... 21<br />

2.2.3 Personal <strong>Culture</strong> and <strong>Security</strong> ................................................................. 22<br />

2.3 <strong>Security</strong> in the Context <strong>of</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> ................................................................... 24<br />

2.3.1 <strong>Security</strong> as the Basis <strong>of</strong> Trust ................................................................. 26<br />

2.3.2 <strong>Security</strong> in the Prevention <strong>of</strong> Fraud and Misuse <strong>of</strong><br />

Information Resources ..............................................................................28<br />

2.3.3 <strong>Security</strong> and Risk Mitigation .................................................................. 29<br />

2.3.4 <strong>Security</strong> as a Strategic Driver ................................................................. 32<br />

2.3.5 <strong>Security</strong> in Systemic Terms .................................................................... 34<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................... 35<br />

3.0 The Benefits <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong>................................................................. 39<br />

3.1 The Benefits <strong>of</strong> Trust ........................................................................................ 40<br />

3.1.1 Internal Trust ............................................................................................ 42<br />

3.1.2 External Trust ........................................................................................... 43<br />

3.2 The Benefits <strong>of</strong> Consistency ............................................................................. 45<br />

3.2.1 Valuing Information ................................................................................ 46<br />

3.2.2 Exception Processes ................................................................................. 47<br />

3.2.3 Risk Management .................................................................................... 47<br />

3.2.4 Predictability ............................................................................................. 48<br />

3.2.5 Standardization ......................................................................................... 49<br />

3.3 Improved Ability to Manage Risk ................................................................... 50<br />

3.4 Improved Return on <strong>Security</strong> Investment ....................................................... 51<br />

3.5 Compliance With Laws and Regulations ........................................................ 53<br />

3.6 Shareholder/Citizen Value ................................................................................ 54<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................... 55<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 5

6<br />

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

4.0 Inhibitors to a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> ..................................................................... 57<br />

4.1 Societal <strong>Culture</strong> ................................................................................................. 58<br />

4.2 Lack <strong>of</strong> Organizational Imperatives................................................................. 59<br />

4.3 Unclear Requirements ....................................................................................... 60<br />

4.4 Insufficiency <strong>of</strong> Awareness Alone ................................................................... 61<br />

4.4.1 Comprehension <strong>of</strong> Risk ........................................................................... 62<br />

4.4.2 The Personal Experience <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> ..................................................... 62<br />

4.5 Systemic Shortcomings ..................................................................................... 64<br />

4.5.1 Inability to Detect Variances From Policy and <strong>Culture</strong> ....................... 66<br />

4.5.2 Inability to Monitor and Enforce Compliance With the <strong>Culture</strong> ......... 67<br />

4.6 Lack <strong>of</strong> Rewards ................................................................................................ 68<br />

4.6.1 <strong>Security</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essionals .............................................................................. 69<br />

4.6.2 Lack <strong>of</strong> Metrics ........................................................................................ 69<br />

4.6.3 Failure to Measure Risk .......................................................................... 70<br />

4.6.4 Lack <strong>of</strong> Incidents ...................................................................................... 71<br />

4.6.5 No Financial Connection ......................................................................... 71<br />

4.7 What Is in It for Me? ......................................................................................... 72<br />

4.7.1 Budget ....................................................................................................... 72<br />

4.7.2 Influence ................................................................................................... 73<br />

4.7.3 Management Attention ............................................................................ 73<br />

4.7.4 Personal Regard........................................................................................ 73<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................... 74<br />

5.0 <strong>Creating</strong> an Intentional <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> ..................................................... 75<br />

5.1 Changing Perceptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> .................................................................... 76<br />

5.1.1 Branding <strong>Security</strong> .................................................................................... 77<br />

5.1.2 Educating About <strong>Security</strong> ....................................................................... 80<br />

5.2 The People Who Make the <strong>Culture</strong> ................................................................. 81<br />

5.2.1 Intentionality ............................................................................................. 82<br />

5.2.2 Finding the Champion ............................................................................. 83<br />

5.2.3 Objects <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Security</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> .................................................................. 84<br />

5.3 Attributes <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Security</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> ....................................................................... 85<br />

5.3.1 <strong>Security</strong> Champions ................................................................................. 85<br />

5.3.2 Budget for <strong>Security</strong> .................................................................................. 86<br />

5.3.3 Broad Accountability ............................................................................... 87<br />

5.3.4 Awareness and Education ....................................................................... 88<br />

5.3.5 Policies, Standards and Guidelines......................................................... 88<br />

5.3.6 Go/No-go Decisions ................................................................................ 89<br />

5.3.7 Rewards ..................................................................................................... 90<br />

5.3.8 Rigorous Response to Breaches .............................................................. 90<br />

5.3.9 Satisfied Customers ................................................................................. 91<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................... 92<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

table <strong>of</strong> ContentS<br />

6.0 Positive Reinforcement ......................................................................................... 93<br />

6.1 Alignment <strong>of</strong> Information <strong>Security</strong> and Business Objectives ....................... 94<br />

6.1.1 <strong>Security</strong> as an Obstacle ............................................................................ 94<br />

6.1.2 Strategic Necessity ................................................................................... 95<br />

6.1.3 Risk Management .................................................................................... 96<br />

6.1.4 <strong>Security</strong> Procedures Embedded in Daily Operations ............................ 98<br />

6.1.5 Management Reward Structure............................................................... 99<br />

6.2 Balance ............................................................................................................. 100<br />

6.2.1 The Burden on <strong>Security</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essionals ................................................ 100<br />

6.2.2 The Burden on the Enterprise ............................................................... 102<br />

6.3 Convergence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Roles ...................................................................... 103<br />

6.4 Automated Cultural Tools .............................................................................. 104<br />

6.4.1 An Architecture for a <strong>Security</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> ................................................ 106<br />

6.5 Stakeholder Feedback ..................................................................................... 109<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................. 110<br />

7.0 Negative Reinforcement ...................................................................................... 113<br />

7.1 Perverse Incentives .......................................................................................... 114<br />

7.2 Vigilance .......................................................................................................... 115<br />

7.2.1 What to Watch ........................................................................................ 115<br />

7.2.2 Who Should Watch ................................................................................ 117<br />

7.3 Automated Detection ....................................................................................... 118<br />

7.4 Alerts, Alarms and Triggers ........................................................................... 119<br />

7.4.1 Alerts ....................................................................................................... 119<br />

7.4.2 Alarms ..................................................................................................... 121<br />

7.4.3 Triggers .................................................................................................. 122<br />

7.5 When All Else Fails ........................................................................................ 123<br />

7.5.1 Penalties .................................................................................................. 125<br />

7.5.2 Defiance .................................................................................................. 126<br />

7.5.3 Career Impact ......................................................................................... 126<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................. 127<br />

8.0 How Good Is Good Enough? ............................................................................. 129<br />

8.1 Getting There ................................................................................................... 131<br />

8.1.1 Establish the Need for Change ............................................................. 132<br />

8.1.2 Communicate the Desired Vision ......................................................... 133<br />

8.1.3 Achieve Initial Objectives ..................................................................... 133<br />

8.1.4 Strike a Balance...................................................................................... 134<br />

8.1.5 Institutionalize the Intentional <strong>Security</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> ................................. 134<br />

8.1.6 Sustain the Intentional <strong>Security</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> .............................................. 134<br />

8.2 Conclusion ........................................................................................................ 135<br />

Endnotes .................................................................................................................. 136<br />

ISACA Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Guidance Publications ......................................................... 137<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 7

8<br />

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

Page intentionally left blank<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

PRefACe<br />

PrefaCe<br />

In October 2010, ISACA published The Business Model for Information <strong>Security</strong><br />

(BMIS). The model takes a business oriented approach to managing information<br />

security, building on the foundational concepts developed by the association. It<br />

utilizes systems thinking to clarify complex relationships within the enterprise and,<br />

thus, to more effectively manage security. 1<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> the BMIS study was that an intentional culture <strong>of</strong> security 2<br />

was the primary objective for the model, as applied to information security. 3 The<br />

intentionality <strong>of</strong> security must be emphasized. Implicit in the use <strong>of</strong> “intentional”<br />

is that enterprises—companies in the private sector, agencies in the public<br />

sector—do not, for the most part, have an effective culture <strong>of</strong> security, one<br />

that supports the protection <strong>of</strong> information while also supporting the broader<br />

aims <strong>of</strong> the enterprise. They must take active, directed steps to improve it. All<br />

enterprises have a culture <strong>of</strong> security. In most cases, it lacks intentionality and is<br />

inconsistent to the extent that it exists at all; in others, it is robust and guides the<br />

daily activities <strong>of</strong> employees and others who come in contact with the enterprise.<br />

Most important, those enterprises with a stronger culture <strong>of</strong> security may not have<br />

created it purposefully; the existence <strong>of</strong> meaningful security is so clearly aligned<br />

with the mission <strong>of</strong> the business that management did not need to apply intentional<br />

measures. Understanding whether the culture was created in a purposeful manner or<br />

by “accident” is critical to sustaining the culture in the long run.<br />

This volume is dedicated to all those who recognize the importance <strong>of</strong> security<br />

and who strive to achieve it. They may feel that their enterprises have given lip<br />

service to security, but do not actually have the firmness and resolution <strong>of</strong> purpose<br />

to receive the full value <strong>of</strong> the investments made in security. The people they work<br />

with say the right things, <strong>of</strong>ten do the right things and even pay for the right things,<br />

but the information with which they carry out their responsibilities is not really<br />

secure. They want to achieve a meaningful, intentional security culture. It is the<br />

purpose <strong>of</strong> this volume to suggest the way to do it.<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 ISACA, The Business Model for Information <strong>Security</strong> (BMIS), USA, 2010<br />

2 Throughout this volume, it is assumed, but not stated, that “security” refers to the<br />

security <strong>of</strong> information resources. If a differentiation is required, it is specified,<br />

e.g., physical, personnel or operations security.<br />

3 ISACA, An Introduction to the Business Model for Information <strong>Security</strong>, 2009, p. 12<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 9

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

10<br />

Page intentionally left blank<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

1.0 IntRoduCtIon<br />

My management just does not “get” information security!<br />

1.0 introduCtion<br />

Our information security department keeps getting more tools, but as a<br />

senior executive, I do not think we are any more secure.<br />

<strong>Security</strong> policy is one thing. Reality is another.<br />

Sure, I support security, but if there is going to be a company to secure,<br />

departments like mine need to make money.<br />

I am so overwhelmed with all the passwords I have to remember; I just<br />

write them down and leave them next to my computer.<br />

I know that I am not supposed to have access to this information, but<br />

I was granted authorization in my old position and just kept it when I<br />

was transferred.<br />

Management has authorized acquisition <strong>of</strong> monitoring tools, but they<br />

did not give me any budget for people to do the monitoring.<br />

All the information security people do is say “no.” They should learn<br />

the way this business really works.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> these comments, and many more like them, are heard in enterprise after<br />

enterprise around the world. Often enough, all <strong>of</strong> these statements may be heard<br />

in the same enterprise, although they do seem mutually contradictory. How can<br />

it be that senior management funds an information security function; provides it<br />

with the latest, most effective tools; and backs those tools with a definitive security<br />

policy, but still does not feel that the enterprise’s information is secure? In fact,<br />

there is sufficient evidence that it is not secure. Somewhere within the workings<br />

<strong>of</strong> the company or government agency, something that should be happening is not<br />

happening. Someone—or many people—is not effectively supporting security.<br />

The missing element is a culture <strong>of</strong> security, defined in BMIS as a pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

behaviors, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes and ways <strong>of</strong> doing things. It is emergent<br />

and learned, and it creates a sense <strong>of</strong> comfort. <strong>Culture</strong> evolves as a type <strong>of</strong> shared<br />

history as a group goes through a set <strong>of</strong> common experiences. Those similar<br />

experiences cause certain responses, which become a set <strong>of</strong> expected and shared<br />

behaviors. These behaviors become unwritten rules that, in turn, become norms<br />

that are shared by all people who have that common history. It is important to<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 11

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

understand the culture <strong>of</strong> the enterprise because it pr<strong>of</strong>oundly influences what<br />

information is considered, how it is interpreted and what will be done with it. 1<br />

Note the importance <strong>of</strong> the terms used in the definition from BMIS:<br />

• Pattern—Not just intermittent, but continuous<br />

• Behaviors—The way people act and not what they say they intend to do<br />

• Beliefs—The core principles that people bring to the world <strong>of</strong> business<br />

• Assumptions—The personal and societal expectations about information and its<br />

protection that binds belief and behaviors<br />

• Attitudes—The perspectives on security that are ingrained in people based on<br />

previous experience<br />

• Ways <strong>of</strong> doing things—The security procedures embedded in day-to-day<br />

operations<br />

A culture arises whenever two or more people are engaged in a common endeavor.<br />

In a business setting, there is a pattern <strong>of</strong> behaviors, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes<br />

and ways <strong>of</strong> doing things that constitute a corporate culture. To the extent that<br />

information is a part <strong>of</strong> that business, there is a component that is a security<br />

culture. It may be weak, ineffective, disorganized, contradictory, unrecognized and<br />

haphazard, but it exists. A security culture exists in every enterprise. It is preferable<br />

that a culture <strong>of</strong> security be strong, effective, well-organized, consistent and<br />

supportive <strong>of</strong> the intentions <strong>of</strong> those in an enterprise who recognize that security is<br />

a strategic attribute and contributes to the overall health <strong>of</strong> the enterprise. That is,<br />

supposedly, the intention <strong>of</strong> management.<br />

Even in enterprises in which there are many <strong>of</strong> the components <strong>of</strong> security—staff,<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware, hardware, procedures, policies and standards—without a culture to bind<br />

them to the overall corporate culture, the best that can be hoped for is mechanistic<br />

compliance with the routine requirements <strong>of</strong> protecting information. It will be<br />

the minimum security that the enterprise can tolerate—meaning it is something<br />

that must be endured or accepted grudgingly. It will not be the degree <strong>of</strong> security<br />

appropriate to that enterprise, in the context <strong>of</strong> the way it does business in its<br />

industry or with its customers or where it is located in the world. <strong>Security</strong> without<br />

culture is insufficient security.<br />

Achievement <strong>of</strong> that level <strong>of</strong> security will not happen by itself—self-generated<br />

and unsystematically. It requires people <strong>of</strong> good intent to take both positive and<br />

punitive measures to strengthen a security culture to a desired level, the level<br />

that management intends it to be or should be in the opinion <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

leadership. For that reason, this volume is focused on the development <strong>of</strong> an<br />

intentional security culture. Yes, a culture <strong>of</strong> security always exists, but an<br />

intentionally strong, effective and resilient security culture requires work, both to<br />

build and maintain it.<br />

12<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

1.0 introduCtion<br />

An enterprise that recognizes that it does not operate with an effective culture <strong>of</strong><br />

security, but that wishes to create one, must establish a systemic viewpoint across<br />

the enterprise with regard to the protection <strong>of</strong> information. It must reconcile all the<br />

contradictory impulses within the enterprise that inhibit the growth <strong>of</strong> security. A<br />

culture cannot be effected quickly, as may the mechanics <strong>of</strong> security. There is no<br />

appliance to install or s<strong>of</strong>tware to implement. It involves the creation <strong>of</strong> a mindset<br />

among the people who make up the enterprise and among those with whom it<br />

comes in contact—vendors, customers, other stakeholders and the society at large.<br />

That mindset, the outlook and attitudes that drive behavior, is the substance <strong>of</strong> a<br />

culture, one that must be implanted, nurtured and accepted gradually. It cannot be<br />

imposed from above, although organizational leadership can lead the way.<br />

Once established, an intentional culture <strong>of</strong> security tends to be forgotten—not the<br />

culture itself, but the intentionality <strong>of</strong> it. At that point, certain behaviors are intrinsic<br />

to the enterprise’s way <strong>of</strong> doing business. For example, in the private sector, there<br />

is no need for an intentional culture <strong>of</strong> sales; sales teams sell products because that<br />

is what they do. It is simply recognized that, without sales, there is no business,<br />

and people act accordingly. An exaggerated sales culture can be disadvantageous to<br />

customer service, pr<strong>of</strong>it or security. In extreme cases, a sales culture can overwhelm<br />

ethics and legality. In the same way, a culture <strong>of</strong> security that is too heavy could<br />

be an impediment to growth or mission achievement. A heavy security culture<br />

could be a business disabler if not properly aligned with the organizational mission<br />

and business functions. It must fit comfortably within the overall culture <strong>of</strong> the<br />

enterprise and become so habitual that it is barely noticed.<br />

1.1 Hard and S<strong>of</strong>t <strong>Security</strong><br />

It is a fallacy to consider the technology and mechanics <strong>of</strong> security as being hard,<br />

while considering those aspects that deal with human factors such as planning,<br />

management, motivation and reward as the s<strong>of</strong>t side <strong>of</strong> security. The word “hard”<br />

has several connotations: impenetrability, difficulty, firmness, factuality, realism<br />

and strictness. In all these senses, it is the development <strong>of</strong> a culture <strong>of</strong> security that<br />

is hard:<br />

• To be impenetrable, a culture <strong>of</strong> security must adapt to changing environments<br />

and contexts as businesses expand or contract, personnel come and go,<br />

management organizes and reorganizes, and technologies foster and inhibit<br />

innovation. No technology is impenetrable, precisely because all technologies are<br />

implemented by people. The effectiveness <strong>of</strong> any implementation is based on the<br />

thoroughness and consistency <strong>of</strong> those who carry it out—in other words, by the<br />

culture in which they do so.<br />

• For those without it, technical skill can be hard to come by, but it can be taught<br />

and it can be learned. A culture must arise and be lived. The latter is far more<br />

difficult than the former.<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 13

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

• Technology may seem firm and unbending: A s<strong>of</strong>tware package will always do<br />

as it is told and a piece <strong>of</strong> equipment will always work the same way—until they<br />

do not. S<strong>of</strong>tware and hardware are engineered artifacts, all <strong>of</strong> which have defects.<br />

Of course, a culture may be defective as well, but it is much more likely to bend<br />

and adapt than to break.<br />

• Similarly, technology is not always factual. Just because a machine produces a<br />

result does not mean that it is the right result. A sound culture must be based on<br />

facts: the way people actually work, the value <strong>of</strong> the information with which they<br />

work and their contradictory impulses that must be accommodated.<br />

• It is odd to think <strong>of</strong> facts as hard and opinions and emotions as s<strong>of</strong>t when the<br />

reality is that many, if not most, people act on the stimuli <strong>of</strong> their emotions and<br />

opinions and not <strong>of</strong> the harsh reality before them. A culture <strong>of</strong> security can be<br />

used to mold opinions across an enterprise much more realistically to the risks <strong>of</strong><br />

their business and the environment in which they perform.<br />

• A culture <strong>of</strong> security is precisely as strict as a given enterprise wants it to be.<br />

There are some types <strong>of</strong> enterprises, such as national intelligence agencies or<br />

banks, in which security is strictly observed. This did not occur haphazardly, but<br />

was a natural consequence <strong>of</strong> business drivers that include pr<strong>of</strong>it and customer<br />

service, to be sure, but also managed risk, achievement <strong>of</strong> organizational mission<br />

and ethics.<br />

There are other meanings <strong>of</strong> security for which a culture must be established to<br />

counter. <strong>Security</strong> should not be oppressive, unrelenting, resentful or troublesome.<br />

<strong>Security</strong> must not be allowed to be considered adverse to mission achievement;<br />

where that is so, there is clear evidence that security is a weak part <strong>of</strong> the overall<br />

corporate culture. It has allowed security to be seen as prohibition rather than<br />

enablement. Among the rationales for a culture <strong>of</strong> security is the alignment <strong>of</strong><br />

security with the business as a whole. The negativity <strong>of</strong>ten associated with<br />

security—locks, barricades, punishment, etc.—undermine its effectiveness. A<br />

culture <strong>of</strong> security is necessary to overcome obstacles <strong>of</strong> those sorts.<br />

A culture <strong>of</strong> security may be seen as s<strong>of</strong>t because it is less tangible, but fuzziness<br />

should not be confused with inaccuracy. <strong>Culture</strong> deals with perceptions, estimations,<br />

preponderances and directions and not with the orderly array <strong>of</strong> numbers that is<br />

found, for example, in accounting or finance. However, perceptions and directions<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten the indicators <strong>of</strong> reality, more so than the seemingly hard numbers that on<br />

closer inspection—or revelation—may be seen as a smokescreen designed to obscure<br />

reality. A culture determines what an enterprise actually does about security (or any<br />

other objective, for that matter) and not what it says that it intends to do.<br />

14<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

1.2 Whose <strong>Culture</strong> Is It?<br />

1.0 introduCtion<br />

A culture <strong>of</strong> security does not belong to an information security department any<br />

more than an ethical culture belongs to a legal department. A culture is generalized<br />

across an enterprise—among executive management and a board <strong>of</strong> directors;<br />

management and staff; revenue producers and their back <strong>of</strong>fice; and salespeople,<br />

computer operators, cleaning staff, etc. It is the organizational zeitgeist, the spirit <strong>of</strong><br />

the times in which an enterprise operates. It is capable <strong>of</strong> change, and it is affected<br />

by the composition <strong>of</strong> the enterprise itself.<br />

Certain functions—such as information security, internal audit, risk management<br />

and corporate security, to name a few—may well have a more leading role in<br />

crafting the culture. These functions exist and are rewarded for being aware <strong>of</strong> the<br />

need for security and generally being favorable to stronger controls. There is a<br />

trap in perceiving these functions as the owners <strong>of</strong> a culture <strong>of</strong> security, as though<br />

excusing other personnel from having to pay attention to it. To the extent that some<br />

are more committed to security than others, a balance must be achieved. However,<br />

all who would wish to be part <strong>of</strong> an enterprise must adapt to its culture and no one<br />

can afford to stand apart and still thrive. A culture <strong>of</strong> security is and must be a<br />

joint endeavor.<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 Ibid., p. 16<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 15

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

16<br />

Page intentionally left blank<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

2.0 a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity in Context<br />

2.0 A CultuRe <strong>of</strong> SeCuRIty In Context<br />

A culture <strong>of</strong> security is a pattern <strong>of</strong> behaviors, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes and<br />

ways <strong>of</strong> doing things that promotes security. As enterprises operate across nations,<br />

they observe that there are multiple levels <strong>of</strong> culture—national culture, industry<br />

culture, organizational culture, functional and departmental culture, pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

culture, and cliques and factions culture. What, then, is secure behavior? What does<br />

it mean to believe in security? What assumptions and attitudes lead to security,<br />

and which need to be suppressed if security is to be achieved? Is there a single,<br />

ordained way <strong>of</strong> doing things that promotes security, with all others undermining<br />

security to some greater or lesser degree?<br />

The answer to these and many more questions that are raised in this volume is<br />

context. A culture <strong>of</strong> security fits within a much broader context <strong>of</strong> how a society<br />

interacts; how an enterprise works; and the moral, ethical, political and economic<br />

belief systems <strong>of</strong> the individual who is a part <strong>of</strong> that culture. No one set <strong>of</strong> behaviors<br />

can be extracted from its context and shown to be secure, or insecure, for that<br />

matter. Even more bedeviling, certain patterns <strong>of</strong> behavior may be secure in routine<br />

circumstances, but become less so in times <strong>of</strong> crisis. For example, a help desk may<br />

usually respond to callers on a first-come, first-served basis, but needs to react<br />

aggressively without respect to the order <strong>of</strong> calls when a network is under attack.<br />

2.1 Doing vs. Believing<br />

Does a person have to believe in security to act securely? What, in fact, does it<br />

mean to believe in security? <strong>Security</strong> is not a religion, so where does belief enter the<br />

discussion? It may be fair to ask for two lists, one <strong>of</strong> secure practices and another <strong>of</strong><br />

dangerous ones. If everyone followed the first and eschewed the second, would that<br />

not create security? Indeed, there is a place for those lists: They are called policy,<br />

standards, guidelines and procedures, which relate the way an enterprise is to go<br />

about its mission. Rules have exceptions, and the people who follow them are not<br />

robots. Judgment; comprehension; and, yes, beliefs enter into the way things actually<br />

work, as opposed to how they are supposed to work.<br />

It is insufficient simply to do what is required because those crafting the requirements<br />

are unable to foresee all <strong>of</strong> the situations in which they are to be applied and there<br />

are exceptions to the rules best left to those who apply them. There needs to be an<br />

understanding on the part <strong>of</strong> those acting on the policies as to why they were written,<br />

for whom they were intended and what the intent <strong>of</strong> the writers was at the time they<br />

were written. It is to be expected that those who issue the policies would be more<br />

conscious <strong>of</strong> and diligent in adhering to the policies than those who receive them.<br />

For the few to achieve their objectives through the efforts <strong>of</strong> many, they need to<br />

convey the rationale behind the policies to their constituencies. In short, they must<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 17

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

communicate a systematic viewpoint that drives the policies and that, in turn, is so<br />

conditioned by the way the policy writers have internalized the need for security that<br />

it may accurately be described as a pattern <strong>of</strong> beliefs.<br />

2.1.1 Ambiguity and Inconsistency<br />

A simple, prescriptive model for developing a secure enterprise also breaks down<br />

in the face <strong>of</strong> the many ambiguities and inconsistencies inherent in the word<br />

“security.” Everyone wants to be secure, but not always at the cost <strong>of</strong> comfort,<br />

flexibility, efficiency or timeliness. <strong>Security</strong> is a desired state, but not at any<br />

price. It does not come risk-free. In fact, true security implies the acceptance <strong>of</strong><br />

a reasonable level <strong>of</strong> risk, which only raises the importance <strong>of</strong> who determines<br />

the reasonability <strong>of</strong> any set <strong>of</strong> decisions or actions. No set <strong>of</strong> policies, standards,<br />

guidelines or procedures can foresee all the circumstances in which they are to be<br />

interpreted. At that point, it is the interpreter who is making the rules, and if that<br />

person is not grounded in a culture <strong>of</strong> security, the likelihood <strong>of</strong> acting in the proper<br />

manner is problematic.<br />

Moreover, there are inherent internal contradictions in the definition <strong>of</strong> “security”<br />

that defy easy interpretation. For example, access control and privacy are two<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> security. Access control demands that the attributes and actions <strong>of</strong><br />

each user be known, while privacy demands that these be obscured. 1 The balance<br />

between these conflicting imperatives is an essential part <strong>of</strong> a security culture.<br />

Frustrating as it may be, there will always be ambiguity in any culture, including<br />

one <strong>of</strong> security. It must deal with the contradictions, shortcomings and just plain<br />

silliness that are a part <strong>of</strong> the human condition. In attempting to overcome this<br />

ambiguity, many turn to automation. If security is needed, at least in part, to control<br />

technology, what better tool than technology to achieve the objective? Sadly, this is<br />

circular reasoning; philosophers and mathematicians have shown that no system can<br />

be validated within itself. 2 In other words, technology will always reach a point at<br />

which it cannot secure itself.<br />

Thus, a culture <strong>of</strong> security does not guarantee an absence <strong>of</strong> breaches nor freedom<br />

from error. It is not the cause <strong>of</strong> security, but rather a necessary context in which<br />

security can be fostered and accepted. It is foundational to the achievement <strong>of</strong><br />

security without any preceding understanding <strong>of</strong> what security is or demands. The<br />

culture does not create security, but true security cannot be created in the absence<br />

<strong>of</strong> a supportive culture.<br />

2.2 <strong>Culture</strong> in Context<br />

Enterprises are organic. That is, all enterprises, beyond the most rudimentary, are<br />

a systematic coordination <strong>of</strong> many discrete and interacting parts. For example, in a<br />

commercial business, there are those who create a product, those who sell it, those<br />

18<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

2.0 a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity in Context<br />

who record and administer the money made, those who control the process, and<br />

those who manage the enterprise as a whole. Each is driven by its own dynamics;<br />

all are working together toward a common goal—or at least should be doing so.<br />

The values, assumptions and attitudes that underlie those goals are referred to as the<br />

“corporate culture” that forms a unifying whole for the enterprise and provides the<br />

context within which events are viewed and understood.<br />

Unfortunately, each part <strong>of</strong> an enterprise sometimes becomes so captivated by its<br />

own imperatives, direction, rewards and penalties that the enterprise’s common,<br />

unitary culture becomes submerged beneath the siloed cultures <strong>of</strong> departments,<br />

locations, functions or pr<strong>of</strong>essions. In some cases, the competing cultures create<br />

tensions that pull on each individual within the enterprise. Some functions may<br />

have a sales culture in which anything done to make a sale is rewarded. Others may<br />

be pr<strong>of</strong>it-oriented, with drivers to both high-margin sales and reduced costs. Still<br />

others may participate in a culture <strong>of</strong> customer service, ethics or growth. Some may<br />

live in a culture <strong>of</strong> security.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> these cultures have a place in any enterprise; they need not be contradictory<br />

to one another. They need to be balanced. Selling is good, but not at all costs.<br />

Customer service is good, but not to the exclusion <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>it. Growth is good, but<br />

not if existing customers are dissatisfied and take their business elsewhere. Recent<br />

news has shown that when a company allows one aspect <strong>of</strong> its culture to become so<br />

dominant that others are crowded out, bad results follow. Unbalanced companies<br />

face devastated morale among employees; poor financial results; mass exodus <strong>of</strong><br />

staff; and, ultimately, the extinction <strong>of</strong> a company.<br />

The culture <strong>of</strong> security is the focus <strong>of</strong> this volume not because it should be<br />

dominant, but because it appears that, in many enterprises, it is unnecessarily<br />

overlooked. Many enterprises today have a function that oversees security. In<br />

fact, they have many such functions, each one focused on the security <strong>of</strong> physical<br />

assets; personnel; operational processes; personal information; data; or, indeed,<br />

information in all its forms. Collectively, they may foster a culture <strong>of</strong> security, but<br />

without active, deliberate, intentional management support, that culture can be so<br />

fractionalized that it is ineffective in the broader enterprise. These functions may<br />

not even recognize that their competing perspectives on security are undermining<br />

the very culture <strong>of</strong> which they would want to be a part. This, in turn, makes it<br />

difficult for those supportive <strong>of</strong> security to balance it with competing cultures.<br />

There are some enterprises in which security, in one form or another, is <strong>of</strong><br />

paramount concern and in which a culture <strong>of</strong> security is dominant. Among these<br />

are national intelligence agencies; the military; and, in a different manner, prisons<br />

and gold repositories. For most other enterprises, it would be distortive if security<br />

were the dominant culture. The intent within BMIS is not for security to dominate,<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 19

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

but for it to be integrated into a unifying whole within the corporate culture. An<br />

intentional culture <strong>of</strong> security does not create values, but heightens them among the<br />

tensions that act on each individual who lives within it.<br />

2.2.1 Societal <strong>Culture</strong> and <strong>Security</strong><br />

It is questionable whether any culture—or, for that matter, any concept <strong>of</strong><br />

security—is applicable to all enterprises in all corners <strong>of</strong> the world, without<br />

consideration <strong>of</strong> national and regional differences. 3 Are the perceptions and the<br />

realities <strong>of</strong> security the same in urban, industrialized societies and those in rural,<br />

agricultural ones? Are they the same in countries thoroughly embedded in global<br />

commercial processes and those with struggling, self-sufficient economies or for<br />

those at war and those enjoying the blessings <strong>of</strong> peace? It is not that there are<br />

national attributes that would affect security in any nation. Characterizing people<br />

from certain places as unethical, sly or lazy is reprehensible, but clearly, there are<br />

differences <strong>of</strong> custom, law, communications, politics and history that make the<br />

realization <strong>of</strong> a Platonic ideal 4 <strong>of</strong> information security unachievable.<br />

There are international standards for security. Most notably, the 27000 series from the<br />

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 5 is the DNA, style guide, metric<br />

system and scoreboard <strong>of</strong> security 6 and is generally accepted to be definitive about its<br />

management. Even in this case, there is a caveat to universality: “within the context<br />

<strong>of</strong> the organization’s overall business risks.” 7 What, then, <strong>of</strong> the context <strong>of</strong> societal<br />

norms and expectations that differ from nation to nation and region to region? For<br />

example, the primary control statement for Data protection and privacy <strong>of</strong> personal<br />

information is “Data protection and privacy shall be ensured as required in relevant<br />

legislation, regulations, and, if applicable, contractual clauses.” 8 Thus, explicitly,<br />

there is no universal meaning for privacy—and, by extension, for confidentiality and<br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> security—but rather reliance on necessarily local laws, regulations and<br />

contracts. The comparison is very clear, for example, across the Atlantic. In the US,<br />

privacy is limited to industry verticals, primarily financial services 9 and health care. 10<br />

In most <strong>of</strong> Europe, privacy is a clearly stated fundamental right across society. 11<br />

Multinational companies and those enterprises that do business internationally<br />

cannot presume that dictates for the security <strong>of</strong> information resources will be<br />

perceived or interpreted in the same way in all locations in which they have<br />

interests. The burden is on the management <strong>of</strong> those enterprises to create their<br />

own cultures <strong>of</strong> security, while respecting the differences <strong>of</strong> milieu in which<br />

they will operate. A Londoner (UK) and a New Yorker (USA) may work for<br />

the same company and adhere to the same corporate goals, but when confronted<br />

with a matter that affects or is affected by considerations <strong>of</strong> security, they very<br />

well may not understand the same words the same way. How much higher would<br />

these societal barriers be in countries that do not share the same language, history<br />

20<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

2.0 a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity in Context<br />

and heritage? A culture <strong>of</strong> security cannot be imposed; it must be created on the<br />

substrate <strong>of</strong> the culture <strong>of</strong> the societies within which it is. Given differences in law,<br />

regulation and national outlook, it is possible that there may be several subcultures<br />

<strong>of</strong> security within one enterprise.<br />

2.2.2 Organizational <strong>Culture</strong> and <strong>Security</strong><br />

Just as culture differs across geographic locations, so a culture <strong>of</strong> security is<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>oundly affected by the industry or industries in which an enterprise operates.<br />

Within industries, there are differences in corporate (and <strong>of</strong>ten divisional) cultures.<br />

In a positive sense, differentiating security along organizational lines is a strength<br />

<strong>of</strong> a security culture. It indicates a balance that reflects the differing needs <strong>of</strong> each<br />

enterprise’s business. A stronger organizational security culture arises when there<br />

is a common security purpose tied to shared beliefs, values and assumptions. For<br />

example, all pharmaceutical companies have concern for the security <strong>of</strong> their<br />

formulas and their clinical research data. Some <strong>of</strong> this is driven by the commercial<br />

need to protect the companies’ intellectual property and, to a different degree,<br />

by the ethical consideration <strong>of</strong> the health and privacy <strong>of</strong> test subjects. Most<br />

drug manufacturers are less focused on security than are, for example, mining<br />

companies, in which the major focus <strong>of</strong> security is on the safety <strong>of</strong> personnel, not<br />

information. How much less powerful is a culture <strong>of</strong> security for a manufacturer <strong>of</strong><br />

commodity products?<br />

Every enterprise has a culture <strong>of</strong> security. The security needs <strong>of</strong> commodity<br />

manufacturing pale beside those <strong>of</strong> developing a cancer therapy, and those <strong>of</strong> large<br />

corporations are greater than those <strong>of</strong> a start-up business. In both cases, though,<br />

there is a culture at work. It may be more robust and accepted in one enterprise<br />

than another, without regard to size or the nature <strong>of</strong> the work. An effective security<br />

culture is simply adapted to the circumstances in which an enterprise finds itself.<br />

In no case is the security culture totally absent; no business accepts an open-door<br />

policy toward its information resources. However, some may not protect the door<br />

very well or even perceive that the door needs to be locked.<br />

This is, again, the concept <strong>of</strong> a culture <strong>of</strong> security in context. If there are no<br />

universals in security, who is to say that one culture is superior to another, or is it<br />

true that there are no universals at all? At some elemental level, there are things<br />

that must be achieved or there is no security: access to resources restricted to<br />

authorized people, breaches detected and repaired, data backed up, and people<br />

held accountable for their actions with regard to information. The thoroughness<br />

with which these are accomplished rests, in part, within an enterprise’s culture <strong>of</strong><br />

security, but not entirely so. Even the best intentioned and motivated employees<br />

may make mistakes, and these, on occasion, have disastrous security consequences.<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 21

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

An organizational culture sets the limits <strong>of</strong> acceptable behavior within that entity.<br />

It may be said that policy, not culture, is the driving force for establishing those<br />

boundaries, but conceptually and legally, what an enterprise does is its policy,<br />

not what its management claims that the company does. Policy is a reflection <strong>of</strong><br />

aspirational goals; in the case <strong>of</strong> security, it describes security as management<br />

wants security to be. The way with which people actually work and protect<br />

information (i.e., the culture <strong>of</strong> security) is reality, and absent any explicit moves<br />

by management to provide disincentives (i.e., punishment) for policy breaches, the<br />

culture <strong>of</strong> security is, in actuality, policy as well.<br />

In some industries, there are regulatory requirements for security that, in a broad<br />

manner, set the context <strong>of</strong> a culture <strong>of</strong> security. That does not mean that all banks,<br />

insurers, brokerages or hospitals have internalized security in the same way or to the<br />

same extent. To much the same degree as unregulated companies, the extent and impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> a culture <strong>of</strong> security is dependent on management’s perception <strong>of</strong> the risk to the<br />

enterprise’s information resources and its willingness (or ability) to fund initiatives that<br />

would strengthen either the culture or specific security measures—or both.<br />

It is possible to achieve a level <strong>of</strong> security appropriate for a given enterprise without<br />

explicit measures to create a culture <strong>of</strong> security because that culture is already there.<br />

In many enterprises, such as in financial institutions, intelligence services and the<br />

military, security is so embedded in management’s perception <strong>of</strong> business risk that<br />

the intentionality <strong>of</strong> the culture is self-evident. It has provided the context in which<br />

an enterprise makes decisions and allocates budgets. The same cannot be said in<br />

reverse. The level <strong>of</strong> security cannot exceed the degree to which an enterprise<br />

embeds security into its culture. In that case, rules will be broken and unenforced,<br />

tools will not be applied, and management will not take action against those who<br />

undermine security.<br />

2.2.3 Personal <strong>Culture</strong> and <strong>Security</strong><br />

Ultimately, all enterprises are made up <strong>of</strong> people. Many, but not by any means<br />

all, <strong>of</strong> the people are employees. Perhaps there was a time when a company or<br />

government agency was solely comprised <strong>of</strong> those on the payroll, but if so, that<br />

time is past. Too many enterprises use contractors, outsourcers, service providers<br />

and temporary staff to accept that only personnel are the people who constitute its<br />

human resources. When discussing the security <strong>of</strong> information, there is a tendency<br />

to think in terms <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> servers, terabytes <strong>of</strong> data or breadth <strong>of</strong> the<br />

network. All <strong>of</strong> those are under the control <strong>of</strong> people, and it is people who are the<br />

carriers <strong>of</strong> the “behaviors, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes and ways <strong>of</strong> doing things”<br />

that are the corporate culture.<br />

People are not tabulae rasae (blank slates). As they enter an enterprise and become<br />

a part <strong>of</strong> its culture, they bring their own set <strong>of</strong> cultural expectations derived from<br />

22<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

2.0 a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity in Context<br />

their parents, siblings, schools and houses <strong>of</strong> worship, friends and relations, and<br />

companies for which they worked previously. It is fair to say that some are affected<br />

with a deep respect for security and that others are not. The reason for this is a<br />

subject for sociologists, psychologists and anthropologists; for most others, it is<br />

sufficient to accept and recognize differences <strong>of</strong> outlook and to find the ways to<br />

incorporate them all under the cultural tent.<br />

People can and do change their cultural perceptions, even if they do not realize it<br />

or even realize that they have cultural perceptions. The accepted norms <strong>of</strong> behavior<br />

are transmitted by many means, and not all <strong>of</strong> them are intentional. Rules <strong>of</strong><br />

confidentiality, for instance, may be documented, but a disapproving glance when<br />

a customer’s name is mentioned can communicate more effectively than an entire<br />

volume <strong>of</strong> policies. It is less clear how a weak culture affects a person whose mores<br />

are more supportive <strong>of</strong> security than those <strong>of</strong> the enterprise. Does someone who is<br />

inclined to respect access rights become unconcerned simply because others do not<br />

share that outlook?<br />

If culture cannot be imposed organizationally, neither can it be achieved by<br />

dictating to individuals against their beliefs. Fortunately, it is the rare soul who is<br />

outright opposed to security. Most <strong>of</strong> the principles <strong>of</strong> security are derived from<br />

precepts that are shared across religions and belief systems around the world: Do<br />

unto others as you would have them do unto you; above all, do no harm; mind<br />

your own business; and do not run with scissors. Deep down, everyone (perhaps<br />

excluding the pathologically dishonest) brings these principles to the business. If<br />

they are not always adhered to in the workplace, as they are not always followed in<br />

the world at large, it is because they come into contention with other core concepts:<br />

Get your work done, a penny saved is a penny earned, or let nothing stand in your<br />

way. Somehow, these latter values seem less virtuous, but virtue, too, is a mindset,<br />

an artifact <strong>of</strong> a culture.<br />

If no one is opposed to security, it is equally true that there are many who are not<br />

vocal in its support. A culture <strong>of</strong> security needs its evangelists and champions, those<br />

who are eager to speak up and set examples for others. True, there are always going<br />

to be those whose moral outlook is clouded by pride, avarice and sloth, to say nothing<br />

<strong>of</strong> stupidity. However, if people are rational actors, they will do the right thing—or at<br />

least the most utilitarian thing—most <strong>of</strong> the time. People hold their beliefs privately,<br />

whether they concern religion, morals or politics. When individuals encounter what<br />

they see (or think they see) as a majority holding different viewpoints, they descend<br />

into a “spiral <strong>of</strong> silence,” becoming less and less likely to speak up for their beliefs<br />

and, thus, reinforcing their minority status and giving credence to the majority. This<br />

is how culture is formed. 12 Only those willing to break out <strong>of</strong> the spiral are able<br />

to change culture; only those committed to secure behavior are able to drive the<br />

transformation toward a culture <strong>of</strong> security.<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d . 23

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity<br />

2.3 <strong>Security</strong> in the Context <strong>of</strong> <strong>Culture</strong><br />

The meaning <strong>of</strong> a “culture <strong>of</strong> security” is not intuitively obvious. Perhaps “culture”<br />

is a hazy concept, but surely “security,” here understood to be “information<br />

security,” is a hard and fast, well-understood term, or perhaps, in the so-called<br />

“information age,” the terms “information” and “security” are so widely used<br />

that a consensus has arisen regarding the connotations <strong>of</strong> these words, separately<br />

and together. In fact, there is lively discussion in both technical and management<br />

circles about the meanings <strong>of</strong> the words and about their application in diverse<br />

environments, such as the military, civilian government agencies and private<br />

companies, and in everyday usage by ordinary citizens. It is clear that the terms do<br />

not mean the same things in all contexts.<br />

For example, the international standards on information security define “security”<br />

and “information” very broadly. 13 Evidently, the very resource to be secured is<br />

thought to be so well understood as not to need a more thorough definition, and<br />

yet, the dictionary <strong>of</strong>fers shadings <strong>of</strong> meaning. “Information” is facts; in this sense,<br />

information is made up <strong>of</strong> things that are known. It is also whatever is conveyed<br />

by a particular sequence <strong>of</strong> symbols, impulses, etc. 14 Thus, information is made<br />

up <strong>of</strong> words, bits and bytes. Information is also the communication <strong>of</strong> knowledge,<br />

which incorporates documents, conversations and networks. Additionally, it is the<br />

sequence <strong>of</strong> bits that produce specific effects, in other words, the programs that<br />

manipulate data. 15 So, information can be both signifier and signified, subject and<br />

object, and data and the people who and machines that manipulate them.<br />

Information may be represented in “digital form (e.g., data files stored on electronic<br />

or optical media), material form (e.g., on paper) and “unrepresented” in the form <strong>of</strong><br />

employee knowledge. Information may be transmitted by various means including:<br />

courier, electronic or verbal communication. “Whatever form information takes,<br />

or the means by which the information is transmitted, it always needs appropriate<br />

protection” (emphasis added). 16 The quote makes a broad statement that all<br />

information always needs protection, albeit at an appropriate level. <strong>Security</strong>, in<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> culture, cannot be so dogmatic. It is fair to question, first, whether<br />

all information requires protection and, second, how appropriateness is to be<br />

determined. In practice, security is whatever level <strong>of</strong> protection the culture will<br />

allow with cognizance <strong>of</strong> differences in approach dependent on the risk related to<br />

different forms, representations, communications, storage and disposal <strong>of</strong> varying<br />

sorts <strong>of</strong> information.<br />

<strong>Security</strong> may be (and <strong>of</strong>ten is) defined solely as confidentiality, integrity and<br />

availability (CIA). Without diminishing these characteristics, security may also be<br />

understood to include privacy (different than confidentiality), authenticity, accuracy,<br />

completeness, recoverability (different than availability) and currency. Yet, this is<br />

24<br />

© 2 0 1 1 I S A C A . A l l R I g h t S R e S e R v e d .

2.0 a <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>of</strong> SeCurity in Context<br />

not the view <strong>of</strong> security in the popular imagination. When (or if) the public at large<br />

thinks <strong>of</strong> security, it is in terms <strong>of</strong> preventing computer hacking and viruses. From<br />

War Games in 1983 to The Taking <strong>of</strong> Pelham 123 in 2009, it is always the bad guys<br />

hacking the system who are stopped, always at the last moment, by the student;<br />

simple, but honest worker; or old codger relying on the tried–and-true methods.<br />

These popular entertainments are not important in themselves, but they mightily<br />

affect the perception <strong>of</strong> those who make up the populations <strong>of</strong> enterprises. The less<br />

these people understand the reality <strong>of</strong> either computers or security, the higher the<br />

barrier to achieving a culture <strong>of</strong> security. In short, the culture <strong>of</strong> security is affected<br />

by the overall culture.<br />

Prevention <strong>of</strong> malicious attacks and malware are indeed a part, but only a part, <strong>of</strong><br />

security, and much, but not all, information is stored and manipulated on computer<br />