Validation of a Revised Visual Analog Scale for Premenstrual Mood ...

Validation of a Revised Visual Analog Scale for Premenstrual Mood ...

Validation of a Revised Visual Analog Scale for Premenstrual Mood ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

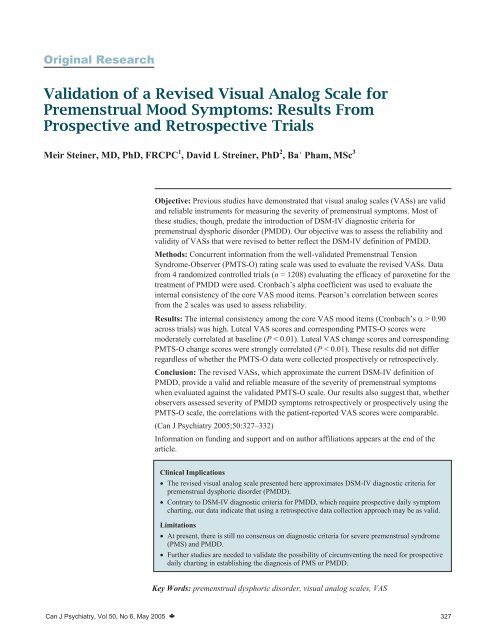

Original Research<br />

<strong>Validation</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Revised</strong> <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Analog</strong> <strong>Scale</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>Premenstrual</strong> <strong>Mood</strong> Symptoms: Results From<br />

Prospective and Retrospective Trials<br />

Meir Steiner, MD, PhD, FRCPC 1 , David L Streiner, PhD 2 ,Ba Pham, MSc 3<br />

Objective: Previous studies have demonstrated that visual analog scales (VASs) are valid<br />

and reliable instruments <strong>for</strong> measuring the severity <strong>of</strong> premenstrual symptoms. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

these studies, though, predate the introduction <strong>of</strong> DSM-IV diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong><br />

premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Our objective was to assess the reliability and<br />

validity <strong>of</strong> VASs that were revised to better reflect the DSM-IV definition <strong>of</strong> PMDD.<br />

Methods: Concurrent in<strong>for</strong>mation from the well-validated <strong>Premenstrual</strong> Tension<br />

Syndrome-Observer (PMTS-O) rating scale was used to evaluate the revised VASs. Data<br />

from 4 randomized controlled trials (n = 1208) evaluating the efficacy <strong>of</strong> paroxetine <strong>for</strong> the<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> PMDD were used. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to evaluate the<br />

internal consistency <strong>of</strong> the core VAS mood items. Pearson’s correlation between scores<br />

from the 2 scales was used to assess reliability.<br />

Results: The internal consistency among the core VAS mood items (Cronbach’s > 0.90<br />

across trials) was high. Luteal VAS scores and corresponding PMTS-O scores were<br />

moderately correlated at baseline (P < 0.01). Luteal VAS change scores and corresponding<br />

PMTS-O change scores were strongly correlated (P < 0.01). These results did not differ<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> whether the PMTS-O data were collected prospectively or retrospectively.<br />

Conclusion: The revised VASs, which approximate the current DSM-IV definition <strong>of</strong><br />

PMDD, provide a valid and reliable measure <strong>of</strong> the severity <strong>of</strong> premenstrual symptoms<br />

when evaluated against the validated PMTS-O scale. Our results also suggest that, whether<br />

observers assessed severity <strong>of</strong> PMDD symptoms retrospectively or prospectively using the<br />

PMTS-O scale, the correlations with the patient-reported VAS scores were comparable.<br />

(Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:327–332)<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation on funding and support and on author affiliations appears at the end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

article.<br />

Clinical Implications<br />

The revised visual analog scale presented here approximates DSM-IV diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong><br />

premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).<br />

Contrary to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong> PMDD, which require prospective daily symptom<br />

charting, our data indicate that using a retrospective data collection approach may be as valid.<br />

Limitations<br />

At present, there is still no consensus on diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong> severe premenstrual syndrome<br />

(PMS) and PMDD.<br />

Further studies are needed to validate the possibility <strong>of</strong> circumventing the need <strong>for</strong> prospective<br />

daily charting in establishing the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> PMS or PMDD.<br />

Key Words: premenstrual dysphoric disorder, visual analog scales, VAS<br />

Can J Psychiatry, Vol 50, No 6, May 2005 327

The Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry—Original Research<br />

The diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong> premenstrual dysphoric disorder<br />

(PMDD), as defined in the DSM-IV, are much stricter<br />

than those <strong>for</strong> premenstrual syndrome (PMS) (1). To apply the<br />

DSM-IV criteria <strong>for</strong> PMDD, women must prospectively chart<br />

symptoms daily <strong>for</strong> at least 2 consecutive symptomatic cycles,<br />

and their chief complaints must include 1 <strong>of</strong> the 4 core mood<br />

symptoms (that is, irritability, tension, dysphoria, and lability<br />

<strong>of</strong> mood) and at least 5 <strong>of</strong> the 11 total symptoms. The charting<br />

<strong>of</strong> symptoms should clearly demonstrate premenstrual worsening<br />

and remission within a few days after the onset <strong>of</strong> menstruation<br />

(“on-<strong>of</strong>fness”) (2). A change in symptoms from the<br />

follicular to the luteal phase <strong>of</strong> at least 50% is suggested <strong>for</strong><br />

the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> PMDD (3,4).<br />

Results from a study <strong>of</strong> women with PMS who sought medical<br />

attention suggest that the DSM-IV criteria <strong>for</strong> PMDD may be<br />

too strict (5). Subjects failing to meet the criteria may still<br />

have substantial premenstrual worsening <strong>of</strong> symptoms.<br />

Prospective daily self-rating <strong>of</strong> symptoms, using reliable and<br />

valid instruments, is essential in making the diagnosis. To<br />

date, there is still no consensus among investigators as to the<br />

best instrument <strong>for</strong> confirming prospectively the diagnosis <strong>of</strong><br />

PMDD, nor is there consensus as to the most appropriate<br />

instrument to measure treatment effects in clinical trials (6).<br />

Previous studies have shown that using a single-item visual<br />

analog scale (VAS) <strong>for</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the 4 core premenstrual mood<br />

symptoms is a reliable and valid method <strong>of</strong> prospective data<br />

collection (3,4). Most <strong>of</strong> these studies, though, predate the<br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong> PMDD,<br />

and previous VASs are not aligned with these criteria. We further<br />

report here on the reliability and validity <strong>of</strong> the VASs that<br />

were revised to better reflect the DSM-IV definition <strong>of</strong><br />

PMDD.<br />

Methods<br />

The analysis used concurrent data from women’s scores on<br />

the revised VASs and the validated <strong>Premenstrual</strong> Tension<br />

Syndrome Observer (PMTS-O) rating scale collected in 4 randomized<br />

controlled trials (n = 1208) evaluating the efficacy <strong>of</strong><br />

different treatment options with paroxetine. In all these trials,<br />

women with premenstrual symptoms that fulfilled the<br />

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong> PMDD signed a written<br />

in<strong>for</strong>med consent <strong>for</strong>m that was approved by the institutional<br />

review board at participating centres.<br />

The validated PMTS-O scale allows an observer to assess<br />

symptoms in 10 domains: irritability or hostility, tension, efficiency,<br />

dysphoria or moodiness, motor coordination, mental–cognitive<br />

functioning, eating habits, sexual drive and<br />

activity, physical symptoms, and social impairment (7).<br />

VASs, together with the PMTS-O scale, have been shown to<br />

be a valid, reliable, and sensitive measure <strong>for</strong> the severity <strong>of</strong><br />

premenstrual symptoms (3). The PMTS-O scale has also been<br />

328<br />

used in subjects with premenstrual symptoms to establish<br />

symptom severity <strong>for</strong> inclusion in clinical studies (8–11) and<br />

to evaluate treatment response in clinical trials (12–15).<br />

In 3 trials with regular visits scheduled during the follicular<br />

phases (that is, each within 3 days after onset <strong>of</strong> menses), 1030<br />

participants were randomized to treatment groups <strong>of</strong> continuous<br />

treatment with paroxetine (12.5 mg daily), paroxetine (25<br />

mg daily), or placebo (16). The trials were conducted according<br />

to an identical protocol with minor language adaptations<br />

<strong>for</strong> different geographic regions <strong>of</strong> Europe and North America.<br />

Participants completed a self-rating set <strong>of</strong> 11 VASs daily<br />

throughout 6 menstrual cycles (2 screening, 1 baseline, and 3<br />

treatment cycles). Single-item VASs were used to measure<br />

each <strong>of</strong> the 4 core mood symptoms (depressed mood, tension,<br />

affective lability, and irritability), as well as the 7 additional<br />

clusters <strong>of</strong> symptoms (decreased interest in usual activities,<br />

difficulty with concentration, lack <strong>of</strong> energy, change in appetite,<br />

change in sleep pattern, feeling out <strong>of</strong> control, and physical<br />

symptoms), in accordance with the DSM-IV criteria <strong>for</strong><br />

PMDD (1). During regular visits, independent observers also<br />

assessed participants by using a retrospective data collection<br />

approach with the PMTS-O scale, prompting <strong>for</strong> the severity<br />

<strong>of</strong> premenstrual symptoms associated with the late luteal<br />

phase <strong>of</strong> the preceding menstrual cycles.<br />

In one trial with regular visits scheduled during the luteal<br />

phases, 178 participants were randomized to treatment groups<br />

receiving continuous treatment with paroxetine (20 mg daily),<br />

intermittent treatment with paroxetine (20 mg daily during the<br />

luteal phase only), or placebo (17). Participants completed a<br />

self-rating, slightly modified (that is, a Swedish version) set <strong>of</strong><br />

10 VASs daily <strong>for</strong> 6 cycles. Single-item VASs were used to<br />

measure each <strong>of</strong> the 4 core mood symptoms (depressed mood,<br />

tension, affective lability, and irritability) as well as 6 additional<br />

clusters <strong>of</strong> symptoms (mood swings, bloatedness,<br />

breast tenderness, lack <strong>of</strong> energy, food cravings, and menstrual<br />

pain). A single observer used a prospective data collection<br />

approach with the PMTS-O scale to assess participants<br />

during their luteal phases.<br />

In all trials, each VAS consisted <strong>of</strong> a 100-mm horizontal line<br />

with vertical line anchors at each end. The anchors were 0 =<br />

“not at all” (that is, “the way you normally feel when you don’t<br />

have premenstrual symptoms”) and 100 = “extreme symptoms”<br />

(that is, “the way you feel when your premenstrual<br />

symptoms are at their worst”).<br />

Data Analysis<br />

All analyses were based on intention-to-treat. For the analyses,<br />

data from the 3 trials with follicular phase visits were<br />

pooled on the basis <strong>of</strong> their identical protocols and the homogeneous<br />

results from the reliability analyses <strong>of</strong> individual trial<br />

Can J Psychiatry, Vol 50, No 6, May 2005

<strong>Validation</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Revised</strong> <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Analog</strong> <strong>Scale</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Premenstrual</strong> <strong>Mood</strong> Symptoms: Results From Prospective and Retrospective Trials<br />

Table 1 Baseline VAS and PMTS-O scores a<br />

VAS mood score<br />

(mm)<br />

Late luteal<br />

phase<br />

Placebo<br />

(n = 349)<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

data. Data from the trial with luteal phase visits were analyzed<br />

separately.<br />

The VAS scores on the 4 core symptoms were averaged to create<br />

a mean score to represent mood symptoms (that is, VAS<br />

mood score) (4). We calculated the VAS total scores (average<br />

<strong>of</strong> 11 symptom scores) only <strong>for</strong> the trials with follicular phase<br />

visits. For the trial with luteal phase visits, the VAS total<br />

scores (average <strong>of</strong> 10 symptom scores) were not derived<br />

because they were not comparable with those derived from the<br />

other trials. We calculated a late luteal phase score (that is,<br />

VAS mood or VAS total), using the average daily VAS scores<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 5 days prior to menses, and a follicular phase score,<br />

using the average <strong>of</strong> daily VAS scores from postmenses days<br />

6to10.<br />

The PMTS-O scale scores 10 domains (outlined above) with<br />

severity ranging from 0 to 4 in 8 subscales and 0 to 2 in 2<br />

domains, <strong>for</strong> a maximum score <strong>of</strong> 36. A PMTS-O mood<br />

subscore includes items from question 1 (irritability or hostility),<br />

question 2 (tension), and question 4 (dysphoria or moodiness)<br />

and ranges from 0 to 12.<br />

Change scores from both VAS and PMTS-O scales were used<br />

to assess sensitivity to symptom worsening or improvement.<br />

A change score was derived by subtracting a baseline score<br />

from the corresponding score at study end (that is, the third<br />

treatment cycle in all trials). For participants who dropped out,<br />

we used the score <strong>of</strong> the last cycle be<strong>for</strong>e early termination.<br />

Trials with follicular phase visits Trial with luteal phase visits<br />

Paroxetine<br />

12.5 mg<br />

(n = 333)<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

Paroxetine<br />

25 mg<br />

(n = 348)<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

Placebo<br />

(n = 59)<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

Intermittent treatment<br />

with 20 mg paroxetine<br />

(n = 60)<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

Continuous treatment<br />

with 20 mg paroxetine<br />

(n = 59)<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

55 (23) 57 (23) 51 (23) 48 (23) 48 (21) 47 (22)<br />

Follicular phase 6 (7) 6 (7) 6 (9) 5 (7) 5 (7) 9 (10)<br />

VAS total score<br />

(mm)<br />

Late luteal<br />

phase<br />

PMTS-O<br />

52 (23) 48 (22) 53 (23) NA NA NA<br />

Follicular phase 6 (7) 6 (8) 6 (8) NA NA NA<br />

<strong>Mood</strong> score 9 (2) 9 (2) 9 (2) 8 (2) 8 (2) 8 (2)<br />

Total score 23 (5) 22 (5) 22 (5) 22 (5) 21 (5) 19 (4)<br />

a<br />

VAS mood score is the average <strong>of</strong> the 4 core mood symptoms (that is, depressed mood, tension, affective lability, and irritability) according to DSM-IV definition<br />

<strong>of</strong> PMDD. VAS total score is the average from the VAS score <strong>of</strong> 11 symptoms according to DSM-IV definition <strong>of</strong> PMDD.<br />

NA = not available (VAS total scores from the trial with luteal phase visits were not comparable with those from the 3 trials with follicular visits.)<br />

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used at baseline to evaluate<br />

the internal consistency <strong>of</strong> the VAS mood items. Baseline<br />

VAS scores were summarized <strong>for</strong> the late luteal and follicular<br />

phases across treatment options. To evaluate construct validity,<br />

we compared VAS mood scores <strong>for</strong> subgroups <strong>of</strong> participants<br />

with varying premenstrual symptom severity according<br />

to a priori defined PMTS-O thresholds. A PMTS-O total score<br />

greater than 27 has been suggested <strong>for</strong> severe symptoms,<br />

between 18 and 27 <strong>for</strong> moderate symptoms, and between 10<br />

and 17 <strong>for</strong> mild symptoms (18,19). Analysis <strong>of</strong> variance was<br />

used to compare subgroups.<br />

Pearson’s correlation was used to compare the DSM-IV VAS<br />

and PMTS-O scores. Both absolute scores at baseline and<br />

change scores were compared. Individual items, mood<br />

domain scores, and total scores were compared.<br />

To examine the construct validity <strong>of</strong> the VAS items relative to<br />

those <strong>of</strong> the PMTS-O scale, pairwise correlation coefficients<br />

were examined between the 4 core mood symptoms in the<br />

VAS scale and the corresponding 3 symptoms from the<br />

PMTS-O scale. Correlation coefficients from 0.3 to 0.5 indicated<br />

moderate association; from 0.5 to 0.7, strong association;<br />

and above 0.7, excellent association (20).<br />

Results<br />

Data from 1208 participants were used in the analyses. In the<br />

trials with follicular phase visits, 1030 participants contributed<br />

data to the baseline analyses and 934 (88%) to the change<br />

Can J Psychiatry, Vol 50, No 6, May 2005 329

The Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry—Original Research<br />

score analyses. For the trial with luteal phase visits, the corresponding<br />

figures were 178 and 165 (93%), respectively<br />

(Tables 1 and 2).<br />

The internal consistency coefficient <strong>for</strong> the luteal VAS mood<br />

score was 0.90 with data from the 3 trials with follicular phase<br />

visits (ranging from 0.90 to 0.91 across trials) and 0.88 with<br />

data from the trial with luteal phase visits. The corresponding<br />

coefficients <strong>for</strong> the follicular VAS mood score were 0.94<br />

(ranging from 0.92 to 0.96 across trials) and 0.91, respectively.<br />

These results indicate a high level <strong>of</strong> internal consistency<br />

among the 4 core mood symptoms.<br />

The VAS mood scores captured the “on-<strong>of</strong>fness” <strong>of</strong> the conditions,<br />

with the mean VAS mood score ranging from 47 to 57<br />

across treatment options <strong>for</strong> the late luteal phase and from 5 to<br />

9 <strong>for</strong> the subsequent follicular phase. Similar results were<br />

observed with the VAS total scores (Table 1).<br />

According to the construct validity criterion, 15% (n = 153) <strong>of</strong><br />

participants in the trials with follicular phase visits experienced<br />

mild premenstrual symptoms; 68% (n = 682), moderate<br />

symptoms; and 17% (n = 171), severe symptoms. The mean<br />

VAS mood score was 41 (95%CI, 38 to 44) <strong>for</strong> participants<br />

with mild symptoms, 54 (95%CI, 52 to 55) <strong>for</strong> those with<br />

moderate symptoms, and 70 (95%CI, 66 to 73) <strong>for</strong> those with<br />

severe symptoms. The mean VAS mood score was significantly<br />

different across symptom severities (F2,1003 = 75.7, P <<br />

0.0001).<br />

Luteal phase VAS scores and corresponding PMTS-O scores<br />

were moderately correlated at baseline (P < 0.01) (Table 2).<br />

330<br />

Table 2 Correlation between luteal phase VAS scores and PMTS-O scores a<br />

Correlation between Baseline<br />

(n = 1030)<br />

VAS depressed mood and PMTS-O dysphoria or<br />

moodiness<br />

VAS affective lability and PMTS-O dysphoria or<br />

moodiness<br />

Trials with follicular phase visits Trial with luteal phase visits<br />

The correlation coefficient between VAS mood and PMTS-O<br />

mood scores was 0.48 <strong>for</strong> the 3 trials with follicular phase visits<br />

(ranging from 0.42 to 0.50 across individual trials) and 0.46<br />

<strong>for</strong> the trial with luteal phase visits. Luteal phase VAS change<br />

scores and corresponding PMTS-O change scores were<br />

strongly correlated (P < 0.01), indicating similar sensitivity to<br />

premenstrual symptom change by both scales. Whether<br />

observers assessed symptom severity retrospectively or prospectively,<br />

the correlations between the patient-reported VAS<br />

scores and the PMTS-O scores were comparable (Table 2).<br />

Corresponding items from the 2 scales (<strong>for</strong> example, VAS<br />

depressed mood and PMTS-O dysphoria or moodiness)<br />

always attained relatively higher correlation values when<br />

compared with correlation between noncorresponding items<br />

(<strong>for</strong> example, VAS depressed mood and PMTS-O tension),<br />

suggesting further evidence <strong>of</strong> the construct validity <strong>of</strong> VAS<br />

items.<br />

Discussion<br />

Change b<br />

(n = 934)<br />

Baseline<br />

(n = 178)<br />

Change b<br />

(n = 165)<br />

0.48 0.52 0.46 0.43<br />

0.46 0.54 0.40 0.35<br />

VAS tension and PMTS-O tension 0.49 0.56 0.64 0.54<br />

VAS irritability and PMTS-O irritability or hostility 0.36 0.57 0.36 0.56<br />

VAS mood and PMTS-O mood 0.47 0.63 0.47 0.51<br />

VAS mood and PMTS-O total 0.45 0.63 0.41 0.46<br />

VAS total and PMTS-O total 0.48 0.63 NA NA<br />

a<br />

VAS mood score is the average <strong>of</strong> the 4 core mood symptoms (that is, depressed mood, tension, affective lability, and irritability) according to DSM-IV definition<br />

<strong>of</strong> PMDD. VAS total score is the average from the VAS scores <strong>of</strong> eleven symptoms according to DSM-IV definition <strong>of</strong> PMDD.<br />

b<br />

Change scores from baseline to trial end (that is, baseline score – end <strong>of</strong> treatment score).<br />

NA = not available (VAS total scores from the trial with luteal phase visits were not comparable with those from the 3 trials with follicular visits.)<br />

Data collected from 4 treatment trials <strong>of</strong> women with severe<br />

premenstrual symptoms indicate that using the revised VASs<br />

(which better reflect the current DSM-IV definition <strong>of</strong><br />

PMDD) provides a reliable measure <strong>of</strong> premenstrual symptoms<br />

when evaluated against the well-validated PMTS-O<br />

scale. The results also suggest similar concurrent validity<br />

between the daily rating <strong>of</strong> symptom severity using the<br />

patient-reported revised VAS and the observers’ rating scale<br />

(PMTS-O), regardless <strong>of</strong> whether the observers assessed the<br />

Can J Psychiatry, Vol 50, No 6, May 2005

<strong>Validation</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Revised</strong> <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Analog</strong> <strong>Scale</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Premenstrual</strong> <strong>Mood</strong> Symptoms: Results From Prospective and Retrospective Trials<br />

premenstrual symptoms with a prospective or retrospective<br />

data collection approach.<br />

The DSM-IV requires women to prospectively chart symptoms<br />

daily <strong>for</strong> a minimum <strong>of</strong> 2 symptomatic cycles to qualify<br />

<strong>for</strong> the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> PMDD and hence meet inclusion criteria<br />

in clinical trials. It has recently been suggested that this may<br />

be impractical as a diagnostic tool in a busy primary care practice.<br />

Not only has it been shown that the requirement <strong>for</strong> prospective<br />

charting may act as a deterrent <strong>for</strong> seeking help, it<br />

may also indicate that patients who participate in clinical trials<br />

are very different from typical PMDD patients seen in primary<br />

care (21).<br />

The revised VAS better reflects the current DSM-IV diagnostic<br />

criteria <strong>for</strong> PMDD, and it is also more user-friendly. As<br />

such, it can potentially increase the accurate identification <strong>of</strong><br />

sufferers and also improve their compliance with treatment.<br />

Most women with severe PMS or PMDD are likely to seek<br />

treatment from their obstetrician-gynecologist or other primary<br />

health care provider. At present, there is still no consensus<br />

on diagnostic criteria <strong>for</strong> severe PMS and PMDD (22).<br />

Recent attempts at circumventing the need <strong>for</strong> a prospective<br />

daily paper and pencil charting are promising (23,24); however,<br />

further validation studies are needed. The data presented<br />

here seem to also indicate that, in women with clear-cut severe<br />

PMS and (or) PMDD, retrospective assessment may be a clinically<br />

acceptable alternative to strict DSM-IV research diagnostic<br />

criteria.<br />

Funding and Support<br />

Funding <strong>for</strong> the project was provided by GlaxoSmithKline.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The authors thank Brian Hunter, Timothy Rolfe, and Reid Robson<br />

<strong>for</strong> their input and support during the project; Tina Haller, Theresa<br />

Chua, and Jenny Huang <strong>for</strong> their assistance with the data analysis;<br />

and Carol Ballantyne and Cindy Tasch <strong>for</strong> their expert help in preparing<br />

the manuscript.<br />

References<br />

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual <strong>of</strong> mental<br />

disorders, 4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994.<br />

p 715–8.<br />

2. Endicott J, Amsterdam J, Eriksson E, Frank E, Freeman E, Hirschfeld R, and<br />

others. Is premenstrual dysphoria disorder a distinct clinical entity? J Womens<br />

Health Gend Based Med 1999;8:663–79.<br />

3. Steiner M, Streiner DL, Steinberg S, Stewart D, Carter D, Berger C, and others.<br />

The measurement <strong>of</strong> premenstrual mood symptoms. J Affect Disord<br />

1999;53:269–73.<br />

4. Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, Carter D, Berger C, Reid C, and others.<br />

Fluoxetine in the treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual dysphoria. N Engl J Med<br />

1995;332:1529–34.<br />

5. Kraemer CR, Kraemer RR. <strong>Premenstrual</strong> syndrome: diagnosis and treatment<br />

experiences. J Womens Health 1998;7:893–907.<br />

6. Born L, Palova E, Steiner M. <strong>Premenstrual</strong> syndromes: guidelines <strong>for</strong> treatment.<br />

In: Gaszner P, Halbreich U, editors. Women’s mental health. Budapest<br />

(Hungary): Section <strong>of</strong> Interdisciplinary Collaboration, World Psychiatric<br />

Association; 2002. p 56 –72.<br />

7. Steiner M, Haskett RF, Carroll BJ. <strong>Premenstrual</strong> tension syndrome: the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> research diagnostic criteria and new rating scales. Acta Psychiatr<br />

Scand 1980;62:177–90.<br />

8. Taskin O, Gokdeniz R, Yalcinoglu A, Buhur A, Burak F, Atmaca R, and others.<br />

Placebo-controlled cross-over study <strong>of</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> tibolone on premenstrual<br />

symptoms and peripheral beta-endorphin concentrations in premenstrual<br />

syndrome. Hum Reprod 1998;13:2402–5.<br />

9. Brown CS, Ling FW, Andersen RN, Farmer RG, Arheart KL. Efficacy <strong>of</strong> depot<br />

leuprolide in premenstrual syndrome: effect <strong>of</strong> symptom severity and type in a<br />

controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84:779– 86.<br />

10. Rausch JL, Janowsky DS, Golshan S, Kuhn K, Risch SC. Atenolol treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord 1988;15:141–7.<br />

11. Maddocks S, Hahn P, Moller F, Reid RL. A double-blind placebo-controlled<br />

trial <strong>of</strong> progesterone vaginal suppositories in the treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual<br />

syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;154:573–81.<br />

12. Condon JT. Investigation <strong>of</strong> the reliability and factor structure <strong>of</strong> a questionnaire<br />

<strong>for</strong> assessment <strong>of</strong> the premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:543–51.<br />

13. Hahn PM, Van Vugt DA, Reid RL. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover<br />

trial <strong>of</strong> danazol <strong>for</strong> the treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendrocrinology<br />

1995;20:193–209.<br />

14. Schmidt PJ, Grover GN, Rubinow DR. Alprazolam in the treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen<br />

Psychiatry 1993;50:467–73.<br />

15. Su TP, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Rosenstein DL, Murphy DL, and<br />

others. Fluoxetine in the treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual dysphoria.<br />

Neuropsychopharmacology 1997;16:346–56.<br />

16. Yonkers KA, Hunter BN, Bellew KM, Rolfe TE, Steiner M, Heller VL.<br />

Paroxetine controlled release is effective in treating premenstrual dysphoric<br />

disorder: a pooled analysis <strong>of</strong> three trials. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:110S–111S.<br />

17. Landen M, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Allgulander C, Nissbrandt H, Gezelius B, and<br />

others. A placebo-controlled trial exploring the efficacy <strong>of</strong> paroxetine <strong>for</strong> the<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual dysphoria [poster presentation, 2002]. Washington<br />

(DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2002.<br />

18. Smith S, Rinehart JS, Ruddock VE, Schiff I. Treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual<br />

syndrome with alprazolam: results <strong>of</strong> a double-blind, placebo-controlled,<br />

randomized crossover clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol 1987;70:37–43.<br />

19. Miner C, Brown E, McCray S, Gonzales J, Wohlreich M. Weekly luteal-phase<br />

dosing with enteric-coated fluoxetine 90 mg in premenstrual dysphoric disorder:<br />

a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Ther<br />

2002;24:417–33.<br />

20. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their<br />

development and use, 3rd ed. Ox<strong>for</strong>d (UK): Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press; 2003.<br />

21. Yonkers KA, Pearlstein T, Rosenheck RA. <strong>Premenstrual</strong> disorders: bridging<br />

research and clinical reality. Arch Women Ment Health 2003;6:287–92.<br />

22. Freeman EW. <strong>Premenstrual</strong> syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder:<br />

definitions and diagnosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003;28(Suppl 3):25–37.<br />

23. Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Hayes-Gill B, Crowe J, O’Brien PM. Menstrual<br />

symptometrics: a simple computer-aided method to quantify menstrual cycle<br />

disorders. Fertil Steril 2002;78:96–101.<br />

24. Steiner M, Macdougall M, Brown E. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool<br />

(PSST) <strong>for</strong> clinicians. Arch Women Ment Health 2003;6:203–9.<br />

Manuscript received April 2004, revised, and accepted July 2004.<br />

1<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Department <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences and<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Obstetrics and Gynecology, McMaster University,<br />

Hamilton, Ontario.<br />

2<br />

Assistant Vice President, Research and Director, Baycrest Centre <strong>for</strong><br />

Geriatric Care; Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Department <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry, University <strong>of</strong><br />

Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.<br />

3<br />

Statistician, BioMedical Data Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Oakville,<br />

Ontario.<br />

Address <strong>for</strong> correspondence: Dr M Steiner, Department <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry and<br />

Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON<br />

L8N 4A6<br />

e-mail: mst@mcmaster.ca<br />

Can J Psychiatry, Vol 50, No 6, May 2005 331

The Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry—Original Research<br />

332<br />

Résumé : <strong>Validation</strong> d’une échelle visuelle analogique révisée des symptômes de<br />

l’humeur prémenstruelle : résultats d’essais prospectifs et rétrospectifs<br />

Objectif : Des études antérieures ont démontré que les échelles visuelles analogiques (EVA) sont des<br />

instruments valides et fiables pour mesure la gravité des symptômes prémenstruels. La plupart de ces<br />

études, cependant, datent d’avant l’introduction des critères diagnostiques du DSM-IV pour le trouble<br />

dysphorique prémenstruel (TDPM). Notre objectif était d’évaluer la fiabilité et la validité des EVA<br />

qui ont été révisées pour mieux refléter la définition du DSM-IV du TDPM.<br />

Méthodes : L’in<strong>for</strong>mation concurrente de l’échelle de mesure bien validée de l’observateur du<br />

syndrome de tension prémenstruelle (PMTS-O) a servi à évaluer les EVA révisées. Les données de 4<br />

essais contrôlés randomisés (n = 1 208) évaluant l’efficacité de la paroxétine pour le traitement du<br />

TDPM ont été utilisées. Le coefficient alpha de Cronback a servi à évaluer la cohésion interne des<br />

principaux items sur l’humeur des EVA. La corrélation de Pearson entre les scores aux 2 échelles a<br />

servi à évaluer la fiabilité.<br />

Résultats : La cohésion interne des principaux items sur l’humeur des EVA (alpha de Cronback ><br />

0,90 dans tous les essais) était élevée. Les scores lutéaux aux EVA et les scores correspondants à la<br />

PMTS-O étaient modérément corrélés à la base (P < 0,01). Les scores de changement lutéaux aux<br />

EVA et les scores de changement correspondants à la PMTS-O étaient <strong>for</strong>tement corrélés (P < 0,01).<br />

Ces résultats ne différaient pas, que les données de la PMTS-O soient recueillies prospectivement ou<br />

rétrospectivement.<br />

Conclusion : Les EVA révisées, qui s’approchent de la définition actuelle du TDPM du DSM-IV,<br />

<strong>of</strong>frent une mesure valide et fiable de la gravité des symptômes prémenstruels, quand elles sont<br />

évaluées par rapport à l’échelle PMTS-O validée. Nos résultats suggèrent également que les<br />

corrélations avec les scores aux EVA déclarés par les patients étaient comparables, que les<br />

observateurs aient évalué la gravité du TDPM prospectivement ou rétrospectivement.<br />

Can J Psychiatry, Vol 50, No 6, May 2005