P3-Vol 2.No3 Dec 96 - International Journal of Wilderness

P3-Vol 2.No3 Dec 96 - International Journal of Wilderness

P3-Vol 2.No3 Dec 96 - International Journal of Wilderness

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

modified this mandate in one corner<br />

where hunting was permitted, and in<br />

another where “scientific forestry” was<br />

to be practiced (Baxter Park Authority<br />

1978). Baxter State Park remains New<br />

England’s largest dedicated wilderness.<br />

Adjacent to the park are several major<br />

state land units and the put-in-point for<br />

the Allagash <strong>Wilderness</strong> Waterway.<br />

Federal <strong>Wilderness</strong><br />

The best-known elements <strong>of</strong> the<br />

region’s wild forest are the federal wilderness<br />

areas, which totaled about<br />

200,000 acres in 1994. These owe their<br />

origin to the establishment <strong>of</strong> national<br />

forests and wildlife refuges earlier in<br />

this century, largely by purchase. In late<br />

1994, only 183,000 <strong>of</strong> the 1.6 million<br />

acres <strong>of</strong> national forest land in the<br />

Northeast were dedicated wilderness,<br />

though road building and logging on<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the remaining area will be limited.<br />

Small wilderness patches exist on<br />

other federal lands.<br />

State and Local<br />

Wild Areas<br />

State and local governments manage<br />

thousands <strong>of</strong> acres <strong>of</strong> forest that would<br />

qualify for inclusion in the wild forest,<br />

as noted in Table 2. The largest example<br />

is the 2.7 million acre New York State<br />

Forest Preserve in the Adirondacks and<br />

the Catskills. Others range from the<br />

14,000 acres <strong>of</strong> natural areas managed<br />

by Vermont’s Department <strong>of</strong> Forests<br />

and Parks to the 170,000 acres <strong>of</strong> designated<br />

wildlands on Pennsylvania’s<br />

state lands, and the preserve lands in<br />

New Jersey’s Pinelands. They could include<br />

Maine’s Bigelow Preserve, although<br />

timber will be harvested there.<br />

Future land use planning on state and<br />

municipal lands may result in more areas<br />

being formally designated for wildness<br />

or wilderness.<br />

Motors: Challenge<br />

to Wildness<br />

Outside <strong>of</strong> the Adirondacks, restrictive<br />

categories <strong>of</strong> wilderness are relatively<br />

new to the Northeast. Much <strong>of</strong> the 5<br />

million-acre wild forest is open to mo-<br />

torized canoes, RVs, and<br />

snowmobiles. <strong>Wilderness</strong><br />

lakes are reached by aircraft<br />

in summer and winter.<br />

As elsewhere, motorized<br />

woods users have<br />

enormous political clout;<br />

their organized opposition<br />

accounts in large part for<br />

the minimal acreage <strong>of</strong><br />

public land designated as<br />

wilderness here. Considering<br />

the impacts <strong>of</strong> motors<br />

on visitor perceptions<br />

<strong>of</strong> wildness, true wilderness<br />

in the region will remain<br />

a chimera unless<br />

some way <strong>of</strong> managing the<br />

impacts <strong>of</strong> motorization is<br />

found. Whether this is<br />

even possible is uncertain.<br />

Additional designations <strong>of</strong><br />

“wilderness” will not be<br />

able to provide visitors<br />

with solitude unless this<br />

issue can be confronted.<br />

A Program<br />

for Wildness<br />

I believe that a sensible conservation<br />

program for the region has two parts:<br />

land acquisition and cooperative landscape<br />

management on private land.<br />

First, I would attempt to increase the<br />

acreage in the publicly owned wild forest<br />

by 50% by the year 2020—from 5<br />

to 7.5 million acres. A significant part<br />

<strong>of</strong> this increase should be allocated to<br />

wilderness. This would still be only<br />

7.5% <strong>of</strong> the region’s land. The effort<br />

should focus on bolstering existing<br />

large and remote publicly owned areas,<br />

especially those with key wildlife<br />

values but would also involve private<br />

groups acquiring small, key parcels. An<br />

enlarged wild forest would be a prize<br />

bequest for this generation to pass to<br />

the future. While there are advocates<br />

<strong>of</strong> single large reserves, I think a case<br />

can be made for a more dispersed approach<br />

that would represent a greater<br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> ecosystems (see, for example,<br />

Maine Audubon Society 19<strong>96</strong>).<br />

But public wildlands will not be<br />

enough. There are innovative ways to<br />

serve long-term land protection goals<br />

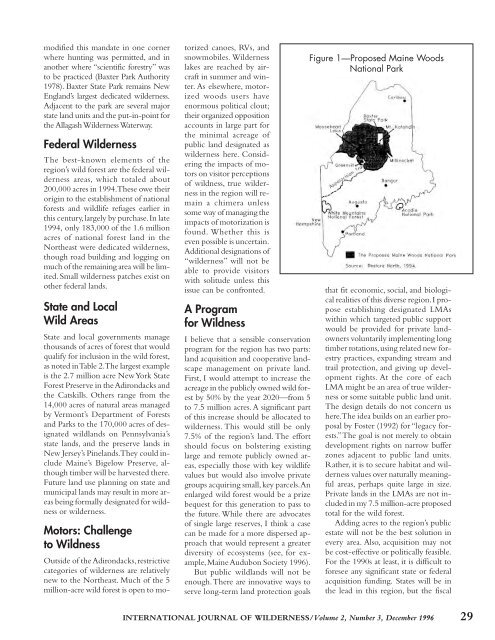

Figure 1—Proposed Maine Woods<br />

National Park<br />

that fit economic, social, and biological<br />

realities <strong>of</strong> this diverse region. I propose<br />

establishing designated LMAs<br />

within which targeted public support<br />

would be provided for private landowners<br />

voluntarily implementing long<br />

timber rotations, using related new forestry<br />

practices, expanding stream and<br />

trail protection, and giving up development<br />

rights. At the core <strong>of</strong> each<br />

LMA might be an area <strong>of</strong> true wilderness<br />

or some suitable public land unit.<br />

The design details do not concern us<br />

here. The idea builds on an earlier proposal<br />

by Foster (1992) for “legacy forests.”<br />

The goal is not merely to obtain<br />

development rights on narrow buffer<br />

zones adjacent to public land units.<br />

Rather, it is to secure habitat and wilderness<br />

values over naturally meaningful<br />

areas, perhaps quite large in size.<br />

Private lands in the LMAs are not included<br />

in my 7.5 million-acre proposed<br />

total for the wild forest.<br />

Adding acres to the region’s public<br />

estate will not be the best solution in<br />

every area. Also, acquisition may not<br />

be cost-effective or politically feasible.<br />

For the 1990s at least, it is difficult to<br />

foresee any significant state or federal<br />

acquisition funding. States will be in<br />

the lead in this region, but the fiscal<br />

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WILDERNESS/<strong>Vol</strong>ume 2, Number 3, <strong>Dec</strong>ember 19<strong>96</strong> 29