General Conclusion form (.pdf)

General Conclusion form (.pdf)

General Conclusion form (.pdf)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

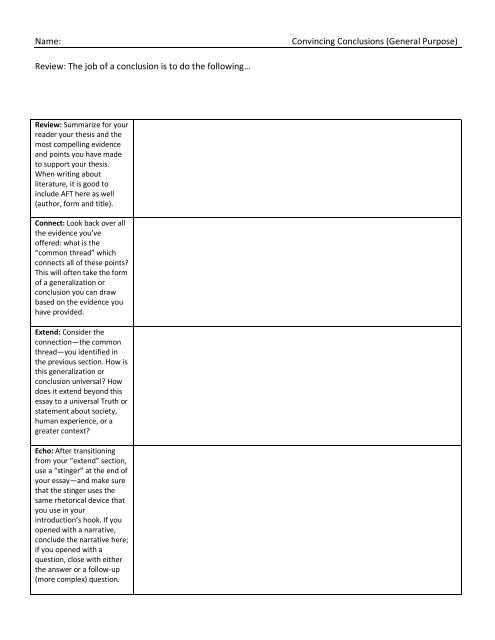

Name: Convincing <strong>Conclusion</strong>s (<strong>General</strong> Purpose)<br />

Review: The job of a conclusion is to do the following…<br />

Review: Summarize for your<br />

reader your thesis and the<br />

most compelling evidence<br />

and points you have made<br />

to support your thesis.<br />

When writing about<br />

literature, it is good to<br />

include AFT here as well<br />

(author, <strong>form</strong> and title).<br />

Connect: Look back over all<br />

the evidence you’ve<br />

offered: what is the<br />

“common thread” which<br />

connects all of these points?<br />

This will often take the <strong>form</strong><br />

of a generalization or<br />

conclusion you can draw<br />

based on the evidence you<br />

have provided.<br />

Extend: Consider the<br />

connection—the common<br />

thread—you identified in<br />

the previous section. How is<br />

this generalization or<br />

conclusion universal? How<br />

does it extend beyond this<br />

essay to a universal Truth or<br />

statement about society,<br />

human experience, or a<br />

greater context?<br />

Echo: After transitioning<br />

from your “extend” section,<br />

use a “stinger” at the end of<br />

your essay—and make sure<br />

that the stinger uses the<br />

same rhetorical device that<br />

you use in your<br />

introduction’s hook. If you<br />

opened with a narrative,<br />

conclude the narrative here;<br />

if you opened with a<br />

question, close with either<br />

the answer or a follow-up<br />

(more complex) question.

Example Introductions and <strong>Conclusion</strong>s: Label the key parts of each…<br />

Introduction: Hook, Bridge, Synopsis, Thesis<br />

<strong>Conclusion</strong>: Review, Connect, Extend, Echo<br />

Private First Class Paul Berlin could<br />

only hear the thunder of his own heartbeat<br />

in his ears. The vivid images bombarded<br />

his mind: the explosion, the blood, the<br />

smoke, the fire. Berlin had no idea the<br />

reaction that this memory would bring out<br />

in him. In Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam war<br />

short story “Where Have You Gone,<br />

Charming Billy?” PFC Berlin experiences<br />

his first few days in country. On his first<br />

day, he watches a man die not of warfare,<br />

but of a fear-induced heart attack. Berlin<br />

retreats into his memories and daydreams<br />

to cope with his fear, but the irony of Billy<br />

Boy Watkins’s death is too much for PFC<br />

Paul Berlin. Berlin’s reaction to Watkins’s<br />

death illustrates the irony of war and how<br />

during war, fear becomes a paradox.<br />

Life and blood are inseparable concepts.<br />

Without blood coursing through one’s<br />

veins, life cannot be sustained. However, in<br />

William Shakespeare’s tragic play<br />

Macbeth, blood represents not life, but<br />

something more sinister. Set in Scotland,<br />

Macbeth chronicles the misguided efforts<br />

of Macbeth, a thane (like a duke), who is<br />

prompted by the prophesies of three<br />

strange witches and the ambition of his<br />

wife to murder King Duncan in order to<br />

become King himself. However, as in all<br />

tragedies, things do not go according to<br />

plan. After murdering Duncan, both<br />

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth experience<br />

crippling guilt that ends them. This guilt is<br />

symbolized throughout the play by<br />

Shakespeare’s blood imagery.<br />

While at war, PFC Paul Berlin in Tim<br />

O’Brien’s short story “Where Have You<br />

Gone, Charming Billy?” reveals the paradox<br />

of wartime fear by laughing hysterically at<br />

the absurdity of Billy Boy’s death. Berlin’s<br />

very obsession with fear turns ironic when it<br />

is that very fear, not a bullet or bomb, which<br />

ends up taking Billy Boy’s life. Berlin’s two<br />

reactions, first daydreaming and then<br />

unstoppable laughter, illustrate an attempt to<br />

cope with the paradoxical ironies inherent in<br />

war. Ultimately, fear underlies both of these<br />

reactions, showing fear can inspire<br />

unexpected and even contradictory<br />

responses. As the fear overtakes PFC Paul<br />

Berlin, laughter overtakes him as well. The<br />

supreme irony of dying from fright while a<br />

soldier in a war zone sends him into<br />

hysterics. But when the laughter stops, the<br />

fear remains.<br />

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the guilt that<br />

both Macbeth and his wife feel for the<br />

murder of King Duncan is overwhelming—<br />

and Shakespeare symbolizes this guilt<br />

through imagery of blood. Through all these<br />

examples, the blood serves as a constant<br />

reminder of Macbeth’s and Lady Macbeth’s<br />

actions, literally staining them with guilt.<br />

This symbolic guilt is visible only to the<br />

guilty parties themselves. Through his<br />

torment of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth,<br />

Shakespeare uses the blood symbolism to<br />

illustrate how guilt can stain a human being<br />

permanently, forever coloring their<br />

existence from the moment of the offense<br />

onward. In effect, then, life and blood are<br />

still in fact inseparable concepts in this play.<br />

However, in Shakespeare’s view, it is not<br />

that blood is life-giving, but that blood on a<br />

guilty hand can be life-staining.