Download Edition - Philadelphia Public School Notebook

Download Edition - Philadelphia Public School Notebook

Download Edition - Philadelphia Public School Notebook

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

NOTEBOOK<br />

VOLUME 13, NO. 4<br />

Details on back page<br />

Join our June 6th Celebration!<br />

District progress<br />

was fueled by<br />

funding increases<br />

by Paul Socolar<br />

Back in 2000, the <strong>School</strong> District of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> was struggling with stagnating<br />

test scores, a systemwide academic crisis, and<br />

looming bankruptcy. <strong>School</strong>s were scraping<br />

by on an austerity budget that amounted to<br />

less than $7,800 per student.<br />

But five years later, the <strong>School</strong> District in<br />

2005 found itself able to spend almost 40 percent<br />

more – $10,800 per pupil, an increase of<br />

$3,000 per student.<br />

Over those five years between 2000 and<br />

2005, the rate of growth in District spending<br />

per student averaged a hefty 7 percent a year,<br />

according to data from the state Department of<br />

Education.<br />

And those significant annual increases in<br />

spending per student were soon accompanied<br />

by significant annual increases in test scores,<br />

at least on most tests in the K-8 grades.<br />

Funding increases fueled a sweeping set<br />

of reform measures undertaken by CEO Paul<br />

Vallas and the <strong>School</strong> Reform Commission<br />

Between 2000 and<br />

2005, growth in<br />

spending per student<br />

averaged a hefty 7<br />

percent a year.<br />

starting in 2002, including a new standardized<br />

curriculum and textbooks, afterschool<br />

programs, a benchmark testing system, new<br />

teacher coaches – even smaller class sizes.<br />

By contrast, the earlier period of austerity<br />

reflected that starting in the mid-1990s and<br />

through the superintendency of David Hornbeck,<br />

the growth in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s per pupil<br />

spending had averaged only 3 percent a year,<br />

hardly enough to cover inflation. In those<br />

years, the District engaged in a war of words<br />

with Harrisburg over the sluggish growth in<br />

state support for schools.<br />

The critical role that increased funding has<br />

played in the recent accomplishments of the<br />

<strong>School</strong> District is drawing attention now, as<br />

the District faces its most difficult budget season<br />

since the system emerged from near-bankruptcy<br />

in 2002.<br />

“It appears that we are dangerously close<br />

to sliding backwards – yet again – to losing<br />

the gains that slowly but decidedly have been<br />

made,” said Shelly Yanoff, executive director<br />

of the child advocacy group <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

Citizens for Children and Youth in testimony<br />

on the District budget at an April <strong>School</strong><br />

Reform Commission meeting.<br />

“We understand that some schools are making<br />

plans to increase class size, to combine<br />

grade levels, to reduce adult resources in<br />

schools,” Yanoff said. “In short, we hear that<br />

schools that are making progress are going to<br />

have to jeopardize that progress by going<br />

against what research and practice tells them<br />

is working – because the budget is being cut.”<br />

See “Budget Tightens” on p. 9<br />

FOCUS ON<br />

Arts and schools<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

■ Most schools cannot afford<br />

both a music and an art<br />

teacher; 66 schools have<br />

neither.<br />

by Dale Mezzacappa<br />

Once, the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>School</strong> District was<br />

a flagship for instruction in the arts, with certified<br />

music and art teachers in virtually every<br />

school. Today, it is struggling to rebuild that<br />

reputation as it faces tighter revenues, a shortage<br />

of qualified teachers, and pressure to spend<br />

more time on reading and math.<br />

Today, less than a third of the city’s public<br />

schools have both art and music teachers. The<br />

majority of the rest have one or the other, but<br />

66 schools have neither, according to a <strong>Notebook</strong><br />

analysis of teacher staffing patterns.<br />

Increasingly, students are getting art and<br />

music instruction through extracurricular programs<br />

and short-term visits from outside artists,<br />

not as part of their everyday learning.<br />

Still, CEO Paul Vallas maintains that the<br />

District is not “shortchanging” the arts. Among<br />

other things, he said, it is one of the few in the<br />

country to write a core curriculum for the arts,<br />

has expanded partnerships with local arts organizations,<br />

plans to open at least two new creative<br />

and performing arts high schools, started<br />

programs in Asian and Puerto Rican music,<br />

and recently invested $1.7 million to buy<br />

instruments to restore high school bands and<br />

orchestras.<br />

“We’ve made progress in all areas except<br />

for full-time art and music teachers,” Vallas<br />

said. “Nobody can tell me there’s been slippage<br />

here on my watch.”<br />

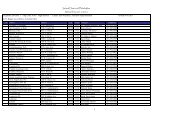

As of May, 133 District schools – 50 percent<br />

– have no full-time music teacher, and<br />

121 have no full-time art teacher (see list, p.<br />

14). These are higher numbers than four years<br />

ago, when <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Citizens for Children<br />

and Youth produced a report on declining numbers<br />

of art and music teachers just before Vallas<br />

took the reins of the District. That report<br />

said 82 schools did not have full-time art teachers,<br />

and 83 lacked full-time music teachers.<br />

Since 2002-03, as District enrollment has<br />

declined, the number of art teachers in the District<br />

has declined by 16 percent, compared to<br />

a reduction in the overall teacher workforce<br />

■ La mayoría de las escuelas<br />

no pueden pagarle a un<br />

maestro de arte y también a<br />

uno de música, y 66 escuelas<br />

no tienen ni uno ni el otro.<br />

por Dale Mezzacappa<br />

Una vez, el Distrito Escolar de Filadelfia<br />

fue un oasis de instrucción en las artes, y prácticamente<br />

cada escuela tenía maestros certificados<br />

de música y de arte. Hoy en día, está<br />

luchando por reconstruir esa reputación mientras<br />

enfrenta menos ingresos, una escasez de<br />

maestros cualificados, y presión para que le<br />

dedique más tiempo a la lectura y a las<br />

matemáticas.<br />

Teaching the<br />

arts in<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

14-15<br />

of 5 percent. For music teachers, the decline<br />

has been about 7 percent.<br />

Racially isolated schools, those at which<br />

more than 90 percent of the students are nonwhite,<br />

are somewhat more likely than other<br />

schools to lack music and art teachers. Seventy<br />

percent of the 66 schools with neither art<br />

nor music are racially isolated, compared to<br />

62 percent of all District schools.<br />

The median poverty rate of the schools with<br />

no art or music teacher is 79 percent, which is<br />

the same as the District’s rate. However, few<br />

magnet schools or schools in the Northeast,<br />

which have the highest percentages of middle-class<br />

students, lack both art and music<br />

teachers.<br />

The decision whether to hire or retain art<br />

and music teachers rests with principals, who<br />

must juggle testing demands and wish-lists<br />

with available funds. Most schools have seen<br />

their budgets and teacher allotments shrink<br />

over the past several years, even as they are<br />

being held more accountable for student<br />

progress.<br />

Vallas said that much of the increase in<br />

schools without music or art is due to deci-<br />

Actualmente, menos de la tercera parte de<br />

las escuelas públicas de la ciudad tienen<br />

maestros de arte y de música. La mayoría de<br />

las demás tienen uno o el otro pero 66 escuelas<br />

no tienen ninguno, de acuerdo a un análisis<br />

que hizo el <strong>Notebook</strong> de los patrones de<br />

contratación de maestros.<br />

Cada vez más, los estudiantes están recibiendo<br />

la instrucción de arte y de música<br />

mediante programas extracurriculares y visitas<br />

a corto plazo de artistas, y no como parte<br />

de su programa diario de aprendizaje.<br />

Aún así, el CEO Paul Vallas sostiene que<br />

el Distrito no está “siendo injusto” con las<br />

artes. Entre otras cosas, dijo, el Distrito es uno<br />

de los pocos en el país que prepara un currículo<br />

básico en las artes, tiene colaboraciones<br />

Principals<br />

keep arts at<br />

the<br />

center<br />

Focus on<br />

Arts and schools<br />

Sección en<br />

español<br />

Table of contents p. 2<br />

www.thenotebook.or<br />

SUMMER 2006<br />

Full-time art, music teachers: a dwindling breed?<br />

Photo: Harvey Finkle<br />

Tenth grader John Vizzachero performs with the saxophone quartet from the High <strong>School</strong> for Creative<br />

and Performing Arts at the May opening of the District’s annual student art show.<br />

sions by education management organizations<br />

(EMOs) to drop those subjects, not to choices<br />

by District-run schools. Over 40 schools<br />

were turned over by the SRC to EMOs in 2002<br />

as part of a privatization reform strategy.<br />

Another factor in the increase in the number<br />

of schools without art or music, Vallas said,<br />

has been the creation of more than a dozen<br />

new small high schools, whose budgets cannot<br />

support a wide diversity of offerings.<br />

“The ideal is to have 17 or 18 kids in each<br />

class and an art and music teacher and librarian<br />

in every school,” said Vallas. “But funding<br />

doesn’t permit that. We’re doing everything<br />

we can within the resources we have.”<br />

The federal No Child Left Behind law<br />

requires schools to improve reading and math<br />

test scores each year. While most city schools<br />

haven’t reached NCLB’s targets, test scores<br />

have been improving overall, especially in the<br />

lower grades.<br />

But for art and music teachers used to<br />

developing children’s creativity on a daily basis<br />

and finding and nurturing raw talent in some of<br />

the city’s poorest neighborhoods, that is small<br />

See “Art, Music” on p. 12<br />

Maestros de arte y música a tiempo completo: cada vez hay menos<br />

expandidas con organizaciones locales de arte,<br />

está planificando abrir dos nuevas escuelas<br />

superiores para artes creativas e interpretativas<br />

en la ciudad, ha comenzado programas en<br />

música asiática y puertorriqueña, y recientemente<br />

invirtió $1.7 millones en la compra de<br />

instrumentos para reestablecer las bandas y<br />

orquestas de las escuelas superiores.<br />

“Hemos progresado en todas las áreas,<br />

excepto en lo que respecta a tener maestros a<br />

tiempo completo de arte y de música,” dijo<br />

Vallas. “Nadie puede decirme que el estándar<br />

ha bajado mientras yo he estado aquí.”<br />

Este mes, 133 escuelas del Distrito – 50 por<br />

ciento – no tienen un maestro a tiempo completo<br />

de música, y 121 no tienen un maestro<br />

“Maestros” continúa en la p. 10<br />

16<br />

State of<br />

the arts:<br />

a roundtable

In Our Opinion<br />

Aren’t the arts essential?<br />

Are courses in the arts a frill – or an essential<br />

part of our vision of schooling?<br />

It is increasingly possible that students<br />

will go through the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> school system<br />

without ever taking an art or music class.<br />

As this edition of the <strong>Notebook</strong> reports, only<br />

half the schools now provide a full-time<br />

music teacher, and the numbers for art aren’t<br />

much better.<br />

<strong>School</strong>s must offer reading, math, and science<br />

to be considered fit to operate. Do offerings<br />

in art, music, drama, and dance belong as<br />

part of the core package every school must<br />

provide?<br />

Few will come right out and say that arts<br />

are a frill. But that is the message being sent<br />

every time an arts program is quietly eliminated<br />

because of insufficient resources or<br />

because reading and math scores are too low.<br />

Cutbacks affecting the arts have been<br />

going on for decades. Allowing schools to<br />

decide whether to offer art or music has accelerated<br />

these cuts. In recent years, pressures<br />

to achieve test score targets under No Child<br />

Left Behind and tightening school budgets<br />

have led dozens of schools to phase out art<br />

and music teaching positions. An array of<br />

central office initiatives to bolster the arts has<br />

not reversed that underlying trend.<br />

When we treat arts as expendable, we<br />

accept a minimalist view of what an education<br />

is – that it is just about providing the<br />

basic skills people need to enter the workforce.<br />

When we treat arts as expendable,<br />

those likely to lose most are students at<br />

schools with the fewest resources or the lowest<br />

test scores – mostly low-income students<br />

and students of color. We risk making our<br />

schools less exciting and less appealing places<br />

to the students whose opportunities are<br />

already the most limited. We put a ceiling on<br />

their aspirations and world.<br />

The arts are an essential component of<br />

schooling for all students. The arts provide<br />

tools to reach students with a variety of personalities,<br />

interests, and learning styles. For<br />

many students, art or music class may be the<br />

only time during school that they genuinely<br />

look forward to, and the resulting sense of<br />

engagement and belonging is often critical<br />

to students’ overall academic achievement.<br />

The arts also provide students with a powerful<br />

means of self-expression and an important<br />

sense of having a voice in the world.<br />

Through art, music, writing, drama, or dance,<br />

students may find a vehicle for defining who<br />

they are and expressing their goals and aspirations.<br />

Students can find community, make<br />

connections, and discover new sides of themselves<br />

through involvement with the arts.<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

An independent quarterly newspaper – a voice<br />

for parents, students, classroom teachers, and<br />

others who are working for quality and equality<br />

in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> public schools.<br />

Leadership Board:<br />

Christina Asquith, Helen Gym, Ajuah Helton,<br />

Myrtle L. Naylor, Dee Phillips, Ros Purnell,<br />

Len Rieser, Toni Bynum Simpkins,<br />

Deborah Toney-Moore, Sharon Tucker,<br />

Ron Whitehorne, Jeff Wicklund<br />

Editor: Paul Socolar<br />

Marketing coordinator: Sookyung Oh<br />

Design: Salvatore Patrone<br />

Cartoonist: Eric Joselyn<br />

Editorial assistance: Eileen Abrams, Elayne<br />

Bender, Joseph Blanc, Roseann Hugh, Ros Purnell,<br />

Len Rieser, Sandy Socolar, Corinne Welsh<br />

Distribution: Eugene Irby, Lonnia Curtis<br />

Web maintenance: Atiya Driver<br />

Interns: Samantha Adler, Carolyn Barschow<br />

Realizing one’s creative abilities is a key<br />

way that youth develop a sense of power and<br />

possibility. With that sense of possibility<br />

comes the ability to imagine change for oneself<br />

or creating a better world.<br />

There also is evidence that exposure to<br />

the arts correlates with academic improvement,<br />

particularly for low-income students.<br />

Studies suggest that involvement in the arts<br />

can support learning by creating a better<br />

school climate, improving critical thinking<br />

and social skills, and increasing student motivation.<br />

But the decision to teach the arts should<br />

not depend on whether or not arts classes<br />

improve reading and math scores. Student<br />

work in the expressive arts has meaning and<br />

value in its own right. The benefits of developing<br />

student creativity are huge, and our<br />

schools need the spirit and sense of community<br />

that the arts can foster.<br />

The baseline for a meaningful arts program<br />

is to provide a full-time art teacher and<br />

music teacher in every school, just as betterfunded<br />

school systems in our region do. Fulltime<br />

arts teachers on staff are vital if we hope<br />

to see any real schoolwide integration of arts<br />

across the curriculum. At large schools, one<br />

art or music teacher won’t be enough.<br />

Arts programs also need well-equipped<br />

physical spaces in our schools. Every student<br />

should have access to art and music classes,<br />

with additional elective opportunities for<br />

interested students.<br />

The <strong>School</strong> District has made progress in<br />

building partnerships with established community-based<br />

and citywide arts organizations,<br />

which are a critical supplement to school programs.<br />

Through artist residencies and other<br />

partnerships, schools can provide exposure<br />

to talented, practicing writers and artists who<br />

can also connect schools to the rich cultural<br />

diversity of our communities. But some fear<br />

that in the absence of a strong commitment<br />

to full-time arts and music staffing, these<br />

short-term arts programs reaching small numbers<br />

of students are now being passed off as<br />

substitutes for a well-staffed, well-equipped<br />

program.<br />

The city of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> will not realize<br />

its strategy for growth as a vibrant center for<br />

arts and culture if its schools are not preparing<br />

students to be part of that. A critical hurdle<br />

in rebuilding a strong arts education program<br />

in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> is securing adequate<br />

school funding. <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s educational,<br />

political, civic, and cultural leaders must<br />

develop a shared vision for delivering quality<br />

arts education to all students as well as a<br />

strategy for garnering the necessary resources.<br />

“Turning the page for<br />

change.”<br />

Editorial Board:<br />

Yulanda Essoka, Eli Goldblatt, Benjamin Herold,<br />

Dale Mezzacappa, Paul Socolar, Eva Travers,<br />

Debra Weiner, Ron Whitehorne, Shelly Yanoff<br />

Special thanks to…<br />

Our subscribers, advertisers, and volunteers who distribute<br />

the <strong>Notebook</strong>. Funding in part from<br />

Bread and Roses Community Fund, Campbell-<br />

Oxholm Foundation, Samuel S. Fels Fund, Allen<br />

Hilles Fund, <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Foundation, Washington<br />

Mutual, and the Henrietta Tower Wurts Memorial –<br />

and from hundreds of individual donors.<br />

The <strong>Notebook</strong> is a member of the Independent Press<br />

Association and the Sustainable Business Network.<br />

Table of contents<br />

Focus on arts and schools<br />

1 Full-time art, music teachers: a dwindling breed?<br />

14 133 schools lack music teacher; 121 lack art teacher<br />

14 Teaching the arts in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>: five schools, five stories<br />

14 Grads talk about the influence of their school years<br />

16 Principals who strive to keep art education at the center<br />

18 Funding seen as key to restoring arts programs in schools<br />

19 Local artists: power of arts education could benefit whole city<br />

20 Participants describe formative experiences with arts education<br />

21 NCLB: taking a toll on arts and music education<br />

22 Two hip-hop enthusiasts connect rapping and reading<br />

24 Lessons from NYC: use city’s resources to restore arts education<br />

26 Understanding the collisions between the arts and literacy<br />

27 Imagining equity in arts education<br />

Other News & Features<br />

1 District progress was fueled by funding increases<br />

4 Groups determined to see high school plans implemented<br />

Departments<br />

2 In Our Opinion 5 Who Ya Gonna Call?<br />

3 Eye on Special Ed 6 News in Brief<br />

3 Letters to the Editors 7 Activism Around the City<br />

3 <strong>School</strong> Snapshot 1, 10-11 Español<br />

More online:<br />

On the web at www.thenotebook.org<br />

About the <strong>Notebook</strong><br />

The mission of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Notebook</strong> is to promote informed<br />

public involvement in the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> public schools and to contribute to the<br />

development of a strong, collaborative movement for positive educational<br />

change in city schools and for schools that serve all children well.The <strong>Notebook</strong><br />

celebrated its tenth anniversary as a newspaper in 2004.<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Notebook</strong> is a project of the New Beginnings Nonprofit<br />

Incubator of Resources for Human Development.<br />

Send inquiries to <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Notebook</strong>, 3721 Midvale<br />

Ave., <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, PA 19129.<br />

Phone: 215-951-0330, ext. 107 • Fax: 215-951-0342<br />

Email: notebook@thenotebook.org • Web: www.thenotebook.org<br />

2 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG SUMMER 2006

State requires schools<br />

to look more closely at<br />

‘least restrictive environment’<br />

by Barbara Ransom<br />

The changes that the Pennsylvania Department of Education<br />

has put into place as a result of amendments to the federal Individuals<br />

with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) and the<br />

recent settlement agreement in the historic Gaskin case are creating<br />

quite a stir in school districts across the state.<br />

The Gaskin lawsuit challenged the Department of Education<br />

to provide more oversight of school districts’ obligation to provide<br />

education in the “least restrictive environment” to children<br />

with individualized education programs (IEPs). The Gaskin case<br />

sought to ensure that school districts provide every school-age<br />

student with a disability the special education and related services<br />

in the least restrictive environment needed to enable the<br />

child to succeed academically.<br />

The settlement of this litigation was a collaboration between<br />

the parties – the Gaskin plaintiffs and the state’s Bureau of Special<br />

Education – intended to benefit all eligible school-aged children<br />

in the Commonwealth.<br />

Spurred on by the settlement and IDEA 2004, the state has<br />

required districts to make significant changes in the development<br />

of a student’s IEP and in placement decisions. Now the team that<br />

develops the IEP must make all placement decisions by first determining<br />

whether the goals they have developed for the student<br />

can be implemented in regular classrooms with supplementary<br />

aids and services.<br />

Supplementary aids and services are any modifications to the<br />

regular education program that a child needs to be fully included,<br />

such as instructional or behavioral aides, facilitated communication<br />

devices, modified curricula, or modified textbooks.<br />

Before the IEP team can consider removing the child from the<br />

regular education classroom, supplementary aids and services<br />

must be provided to include the child to the maximum extent<br />

appropriate.<br />

<strong>School</strong> districts can still assert that education in the regular<br />

classroom is not possible if:<br />

EYE ON SPECIAL EDUCATION<br />

• the child’s disabilities are so severe<br />

that he or she will receive little or no benefit<br />

from inclusion;<br />

• he or she is so disruptive as to significantly<br />

impair the education of other children<br />

in the class; or<br />

• the cost of providing an inclusive education will<br />

significantly affect other children in the district.<br />

This requirement obviously provides some new challenges<br />

for <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, where almost 24,000 children<br />

have IEPs, and many students have “high-incident” classifications<br />

–58 percent with a learning disability, 10 percent with emotionally<br />

disturbed (ED) labels, and 14 percent with mental retardation<br />

(MR) labels. The District’s exclusion of children with MR<br />

and ED labels from regular classrooms has become more the<br />

norm than the exception.<br />

A parent must be alert to the factors that challenge a child’s<br />

ability to receive an appropriate education in the least restrictive<br />

environment and not let the school turn molehills into mountains.<br />

It helps for parents to get to know their child’s teachers and the<br />

building staff; to be a presence in the school; to insist on recordkeeping<br />

and receiving information about any incidents that occur;<br />

and to review the child’s records periodically.<br />

The state has produced an amended IEP form, including a<br />

number of changes as part of the Gaskin agreement. For example,<br />

in completing Section VII, which pertains to educational<br />

placement, the IEP team must now explain any limits on participation<br />

in the general education curriculum with non-disabled<br />

peers. The team must also identify the modifications that the<br />

child needs in order to be included and explain whether the child<br />

will participate in extracurricular and non-academic activities.<br />

In just the first six months of the five-year Gaskin agreement,<br />

three other major provisions have been implemented. A panel<br />

consisting mainly of parents now advises the Bureau of Special<br />

Education on the implementation of the agreement. The state<br />

has begun monitoring the districts with the worst performance<br />

in meeting the IDEA’s “least restrictive environment” mandate,<br />

including <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. The state has also begun awarding minigrants<br />

of $3,500 to $30,000 to school districts this school year.<br />

To date, only one public school in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, Shaw Middle<br />

<strong>School</strong>, has applied for and received a mini-grant.<br />

The panel meets quarterly and already has provided valuable<br />

input toward effective implementation of the agreement. The<br />

next panel meeting – which includes a public portion – will be<br />

held June 27-28 in State College.<br />

Barbara Ransom, Esq. is an attorney at the <strong>Public</strong> Interest<br />

Law Center of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. She served as co-counsel in Gaskin<br />

v. Commonwealth, which was filed on June 30, 1994 and settled<br />

on September 19, 2005.<br />

New admissions policy threatens<br />

equal enrollment opportunities<br />

To the editors:<br />

The <strong>School</strong> Reform Commission’s new enrollment policy<br />

giving Center City residents preference for Center City schools<br />

is a setback for school choice in the District and should alarm<br />

city families seeking access to Center City’s most sought-after<br />

schools. This controversial policy risks isolating thousands of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> K-8 students in struggling schools. These students<br />

deserve equal access to the District’s most prospering schools.<br />

Under the old admissions policy, children within a school’s<br />

immediate boundaries always had a guaranteed seat. But everyone<br />

else in the District, whether they lived in Center City or not,<br />

had an equal opportunity to fill the remaining seats. Now everyone<br />

outside the Center City Region is being pushed back. All of<br />

the regions in the District will have this “regional preference”<br />

enrollment policy by 2010.<br />

The Center City Region is where most parents living near<br />

failing schools are likely to turn. Many of the city’s most desirable<br />

schools are located there, and these schools have more<br />

developed academic and enrichment programs than the other<br />

regions. That’s why parents send students to the region in droves.<br />

Thirty-five percent of its students live outside of the region,<br />

more than in any other region. Getting <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s children<br />

from worse-off regions into these desirable schools just got that<br />

much harder.<br />

What is left for those children who can’t get by the new<br />

admission priorities? They risk being stuck at the bottom end<br />

of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s unequally performing district. In spite of the<br />

District’s welcome efforts to equalize educational opportunities,<br />

the city’s schools are hardly on an equal playing field. Even<br />

a Herculean effort by the District will not equalize the quality<br />

of education offered across the District by the time the new policy<br />

is in full effect. Given these realities, it’s clear that poorer<br />

families with fewer resources now face fewer choices.<br />

The rushed and secretive process with which this policy was<br />

enacted did not adequately include the input of city parents and<br />

education advocates. The commission should have taken the<br />

time to address their questions and concerns before going forward<br />

with a policy change of this magnitude.<br />

In spite of the District’s attempts to downplay the impact of<br />

this policy, parents should be concerned. It is their children’s<br />

educations that will suffer if the District is wrong.<br />

Blondell Reynolds-Brown<br />

City Council<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

What’s YOUR opinion?<br />

We want to know!<br />

Write a letter to<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Notebook</strong> at:<br />

3721 Midvale Avenue<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, PA 19129<br />

Fax: 215-951-0342<br />

Email: notebook@thenotebook.org<br />

Web: www.thenotebook.org/contact<br />

Photo: Amy Kapp<br />

Letters to the editors<br />

Students Rahkeisha Bingham,<br />

Rudy Fields, and Kameelah<br />

Alexander (l. to r.) joined 200<br />

YouthBuild <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Charter<br />

<strong>School</strong> students, staff, and community<br />

members in cleaning<br />

seven abandoned lots on South<br />

Mole Street near Ellsworth St.<br />

on April 21 in celebration of<br />

National Youth Service Day.<br />

YouthBuild is stabilizing vacant<br />

lots on this block where it is in<br />

the last stage of rehabilitating<br />

four houses for low-income<br />

families. YouthBuild offers a<br />

10-month diploma program for<br />

out-of-school-youth, blending<br />

academics with community service<br />

experience and on-the-job<br />

training in construction,<br />

technology or nursing.<br />

Concerns over dumped milk and juice<br />

To the editors:<br />

I have witnessed milk, juice, and food in closed containers in the<br />

dumpster outside a local school. These foods were not out of date.<br />

The school was throwing away one or two big boxes of milk<br />

or juice whenever I checked (two or three times a week). Each<br />

box, I think, was about 5 gallons of milk or juice in little fourounce<br />

containers.<br />

If the food cannot be used in the school, can’t it be donated<br />

to a food bank?<br />

Rachel Frankel<br />

Fishtown<br />

Editors’ note: We posed the question to Wayne Grasela, head<br />

of food services for the <strong>School</strong> District. He maintained that District<br />

waste of food is low due to conservative ordering. But some<br />

unopened items do get discarded – once food items are taken<br />

by students, they must be consumed or discarded, he said.<br />

Regulations require the <strong>School</strong> District to reduce waste.<br />

Grasela said in a statement, “When students select their meals<br />

they have the option of denying two items of a five-item lunch<br />

and one item of a four-item breakfast. If students still have food<br />

they do not want they are encouraged to share it with another<br />

student by placing their unopened or unused food items on a<br />

sharing table centrally located in the cafeteria.”<br />

The case described seems to involve cartons of food that had<br />

not ever been served to students. Grasela said that any school<br />

suspected of wasting food should be reported to the District‘s<br />

Inspector General’s Office at 215-400-4030.<br />

SUMMER 2006 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG 3

‘Sustainability circles’press for small school vision at West and Kensington high schools<br />

Groups determined to see high school plans implemented<br />

by Paul Socolar<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> has seen more than a few lofty<br />

plans for high school reform go unfulfilled. But<br />

in both West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and Kensington,<br />

where community members have worked for<br />

months to develop a vision and plan for reforming<br />

their neighborhood high schools, there is<br />

an organized effort to make sure that these latest,<br />

ambitious reform plans come to fruition.<br />

Few <strong>Philadelphia</strong> high schools have as<br />

much room for improvement as Kensington<br />

and West <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

high schools, both<br />

reporting that half or<br />

less of their students<br />

graduate and more<br />

than one-fourth are<br />

absent daily.<br />

At a May 10<br />

<strong>School</strong> Reform Commission<br />

(SRC) meeting,<br />

six speakers from<br />

the West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> High <strong>School</strong> community<br />

presented their shared vision of a high school<br />

campus of four small schools, while expressing<br />

their determination to bring a change to the<br />

quality of education and student life at West<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> as quickly as possible.<br />

Since 2003, West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> has been<br />

promised a replacement high school building<br />

Speakers from West<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> presented<br />

their shared vision of a<br />

high school campus of<br />

four small schools.<br />

as part of the <strong>School</strong> District’s capital plan.<br />

“Every day I walk into West <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

High <strong>School</strong>, and I feel like I’m walking into<br />

a prison,” junior David James told the SRC.<br />

West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> senior Raymond<br />

Williams described the profound impact of a<br />

trip he took, organized by the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Student<br />

Union, to a successful small school in the<br />

Bronx that maintains a safe environment without<br />

metal detectors or student ID cards because<br />

the school is such a tight-knit community.<br />

Tenth-grader<br />

Tiffany Fogle talked<br />

about an academic<br />

vision for a new West<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> High that<br />

would be based upon<br />

“the three R’s — rigor,<br />

relevance and relationships,”<br />

while using<br />

hands-on learning and<br />

tackling “real-world<br />

community problems.”<br />

These three students were among 180 community<br />

stakeholders who took part in a recent<br />

seven-month planning process for the proposed<br />

new school, led by Concordia, an architectural<br />

consulting firm.<br />

<strong>School</strong> District CEO Paul Vallas called the<br />

resulting plan for the construction of a campus<br />

JOIN THE<br />

CELEBRATION!<br />

June 6th, 2006<br />

(see the back page for details)<br />

of small schools in West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> “splendid”<br />

and added, “Hopefully we’re close to a<br />

community consensus on where the site of the<br />

school should be.” The <strong>School</strong> Reform Commission<br />

needs to settle on a location for construction<br />

to move forward, he added.<br />

“The quickest way to get this school built<br />

is to do it on the present athletic field,” Vallas<br />

added. “That way we wouldn’t have to relocate<br />

the kids until the school is built.” Vallas<br />

said construction could be completed by 2009.<br />

While in West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> it was a chapter<br />

of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Student Union that provided<br />

the impetus for a planning process, in<br />

Kensington, it was the student group Youth<br />

United for Change that led in pressing for a<br />

new high school and demanding a community<br />

voice in the plans. A similar planning<br />

process, led by Concordia, was conducted for<br />

both schools.<br />

Kensington, with its 1400 students, was broken<br />

into three small high schools last year, and<br />

the District’s capital plan includes construction<br />

of a new building for a fourth small high school<br />

in that community. A “Sustainability Circle”<br />

has been created at Kensington to encourage<br />

ongoing community efforts to improve the<br />

schools.<br />

“The value of this community-based process<br />

See “small school plans” on p. 5<br />

4 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG SUMMER 2006

Will small school plans be implemented?<br />

continued from p. 4<br />

has been bringing people together who learned<br />

that they share similar ideas about strengthening<br />

their neighborhood school and about build-<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s<br />

small high schools: schools<br />

with 500 or fewer students<br />

(listed in order by high school enrollment - smallest to largest)<br />

2005-06 grade configuration in parenthesis<br />

<strong>School</strong>s marked with * are adding to or<br />

changing their grade configuration<br />

Phila. Military Academy at Elverson (grade 9)*<br />

Phila. HS for Business & Technology (9-12)<br />

Douglas (9-12)<br />

Motivation (9-12)<br />

Carroll (9-12)<br />

Girard Academic Music Program - GAMP (5-<br />

12)<br />

Leeds Military Academy (9-10)*<br />

Parkway Northwest (9-12)<br />

Rhodes (6-11)*<br />

Lankenau (9-12)<br />

Kensington - Culinary Arts (9-12)<br />

Robeson - Human Services (9-12)<br />

FitzSimons (6-11)*<br />

Parkway - Center City (9-12)<br />

Vaux (9-11)*<br />

Kensington - Creative and Performing Arts (9-<br />

12)<br />

Randolph (9-12)<br />

Parkway West (9-12)<br />

Masterman (5-12)<br />

Kensington Business, Finance<br />

and Entrepreneurship (9-12)<br />

Lamberton HS (9-12)<br />

Communications Technology (9-12)<br />

ing partnerships,” said Tia Keitt, small schools<br />

project coordinator at the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Education<br />

Fund. The Ed Fund has been a facilitator<br />

of the planning process at both Kensington and<br />

West <strong>Philadelphia</strong> high schools.<br />

Keitt explained that the community members<br />

who continue to meet in Kensington “have<br />

By fall, the District will<br />

have added 22 schools<br />

to its high school roster<br />

since 2003<br />

decided to continue to push for a new school<br />

and to try to get the community’s recommendations<br />

implemented.”<br />

Elsewhere, five new high schools are slated<br />

to open in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> this fall. For the past<br />

three years, the District has been creating smaller<br />

schools by dividing up existing large high<br />

schools, making annexes or branches into separate<br />

schools, and converting middle schools<br />

to high schools as part of the District’s “Small<br />

<strong>School</strong>s Transition Project.”<br />

By fall, the District will have added 22<br />

schools to its high school roster since 2003,<br />

nearly all of them with fewer than 500 students<br />

(see list).<br />

CEO Vallas said the District’s efforts to<br />

downsize high schools would continue. Besides<br />

the plans for a new high school in Kensington<br />

and the small schools conversion in West<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, other small schools in the works<br />

for 2007 and beyond include a University of<br />

Pennsylvania-sponsored school on international<br />

affairs, a creative and performing arts<br />

school in the former Rush Middle <strong>School</strong>, and<br />

conversion of Pickett and Sulzberger middle<br />

schools into high schools.<br />

<strong>School</strong> District of <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

Paul Vallas (Chief Executive Officer): 215-400-4100<br />

Gregory Thornton (Chief Academic Officer):<br />

215-400-4200<br />

Regional Superintendents<br />

Janet Samuels (Center City): 215-351-3807<br />

B. Lefra Young (Central): 215-684-8487<br />

Lucy Rodríguez-Feria (Central East): 215-291-5680<br />

Gregory Shannon (CEO Region): 215-684-5132<br />

Marylouise DeNicola (East): 215-961-2066<br />

Lissa Johnson (EMO Region): 215-299-3652<br />

Wendy Shapiro (North): 215-456-0998<br />

Harris Lewin (Northeast): 215-281-5903<br />

Linda Grobman (Northwest): 215-248-6684<br />

John Frangipani (South): 215-351-7445<br />

Harry Gaffney (Southwest): 215-727-5920<br />

Shirl Gilbert (West): 215-471-2271<br />

<strong>School</strong> Reform Commission<br />

James E. Nevels: 215-400-6272<br />

Martin Bednarek: 215-400-6276<br />

Sandra Dungee Glenn: 215-400-6275<br />

James P. Gallagher: 215-400-6273<br />

Daniel J. Whelan: 215-400-6274<br />

City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

Mayor John Street (D): 215-686-2181<br />

City Council Members-At-Large<br />

(elected citywide)<br />

W. Wilson Goode, Jr. (D): 215-686-3414<br />

Jack Kelly (R): 215-686-3452<br />

James F. Kenney (D): 215-686-3450<br />

Juan Ramos (D): 215-686-3420<br />

Blondell Reynolds Brown (D): 215-686-3438<br />

Frank Rizzo (R): 215-686-3440<br />

District City Council Members<br />

Frank DiCicco (D): 215-686-3458<br />

Anna Verna (D): 215-686-3412<br />

Jannie L. Blackwell (D): 215-686-3418<br />

Michael A. Nutter (D): 215-686-3416<br />

Darrell L. Clarke (D): 215-686-3442<br />

Joan L. Krajewski (D): 215-686-3444<br />

Donna Reed Miller (D): 215-686-3424<br />

Marian B. Tasco (D): 215-686-3454<br />

Brian J. O’Neill (R): 215-686-3422<br />

Who ya gonna call?<br />

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania<br />

Governor<br />

Ed Rendell (D): 717-787-2500<br />

State Senators<br />

Vincent J. Fumo (D): 215-468-3866<br />

Christine Tartaglione (D): 215-533-0440<br />

Shirley M. Kitchen (D): 215-457-9033<br />

Michael J. Stack (D): 215-281-2539<br />

Vincent Hughes (D): 215-471-0490<br />

LeAnna Washington (D): 215-242-0472<br />

Anthony Hardy Williams (D): 215-492-2980<br />

Susan Cornell (R): 215-674-3755<br />

State Representatives<br />

Louise Williams Bishop (D): 215-879-6625<br />

Thomas Blackwell (D): 215-748-7808<br />

Mark B. Cohen (D): 215-924-0895<br />

Angel Cruz (D): 215-291-5643<br />

Lawrence H. Curry (D): 215-572-5210<br />

Robert C. Donatucci (D): 215-468-1515<br />

Dwight Evans (D): 215-549-0220<br />

Harold James (D): 215-462-3308<br />

Babette Josephs (D): 215-893-1515<br />

William F. Keller (D): 215-271-9190<br />

George T. Kenney, Jr. (R): 215-934-5144<br />

Marie A. Lederer (D): 215-426-6604<br />

Kathy Manderino (D): 215-482-8726<br />

Michael P. McGeehan (D): 215-333-9760<br />

John Myers (D): 215-849-6592<br />

Dennis M. O’Brien (R): 215-632-5150<br />

Frank L. Oliver (D): 215-684-3738<br />

Cherelle Parker (D): 717-783-2178<br />

John M. Perzel (R): 215-331-2600<br />

William W. Rieger (D): 215-223-1501<br />

James R. Roebuck (D): 215-724-2227<br />

John J. Taylor (R): 215-425-0901<br />

W. Curtis Thomas (D): 215-232-1210<br />

Ronald G. Waters (D): 215-748-6712<br />

Jewell Williams (D): 215-763-2559<br />

Rosita C. Youngblood (D): 215-849-6426<br />

U.S. Congress<br />

Senator Arlen Specter (R): 215-597-7200<br />

Senator Rick Santorum (R): 215-864-6900<br />

Rep. Chaka Fattah (D): 215-387-6404<br />

Rep. Robert Brady (D): 215-389-4627<br />

Rep. Allyson Y. Schwartz (D): 215-335-3355<br />

Rep. Michael Fitzpatrick (R): 215-752-7711<br />

To find out which District City Council member, State Senator, State Representative, or Congressperson<br />

represents you, call the League of Women Voters at 1-800-692-7281, ext. 10.<br />

SUMMER 2006 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG 5

Hayre Institute will aid in<br />

teacher diversity campaign<br />

A <strong>Philadelphia</strong>-based institute aimed at<br />

training student teachers as urban classroom<br />

specialists and then recruiting them to full-time<br />

jobs in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> schools highlights the fivepoint<br />

action plan of a new campaign for<br />

improving the diversity of the District’s teacher<br />

workforce.<br />

The Dr. Ruth Wright Hayre Urban Teaching<br />

Institute, which will recruit college students<br />

nationally and then prepare up to 100 student<br />

teacher “fellows” each year for urban teaching<br />

positions, is slated to open in September 2006.<br />

The announcement was made by <strong>School</strong> District<br />

officials, U.S. Representative Chaka Fattah, and<br />

other partners at a joint April news conference.<br />

Temple University’s College of Education and<br />

the American Association of Colleges for Teacher<br />

Education are supporting the effort.<br />

At least 50 percent of the institute’s fellows<br />

will be teachers of color. Congressman Fattah<br />

pledged to secure a grant to support the institute.<br />

“Urban teaching is a specialty,” said <strong>School</strong><br />

Reform Commissioner Sandra Dungee Glenn,<br />

who has pushed for the teacher diversity campaign.<br />

She added, “And there<br />

are myths about the urban<br />

classroom that we want to<br />

explode.”<br />

The institute is named for<br />

the first full-time African<br />

American teacher in the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> public<br />

school system, who was also the first African<br />

American senior high school principal and the<br />

first African American and woman president<br />

of the Board of Education.<br />

Dungee Glenn said that to improve the<br />

effectiveness of the teacher workforce, action<br />

was needed to narrow the substantial gap<br />

between the total percentage of teachers of<br />

color in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> – 38 percent – and the<br />

combined percentage of Black, Latino, and<br />

Asian students – more than 85 percent.<br />

Other components of the teacher diversity<br />

News<br />

In Brief<br />

campaign include:<br />

• new marketing efforts aimed at recruiting<br />

teachers from universities with large African<br />

American and Latino enrollments in nearby<br />

states and Puerto Rico.<br />

• a test preparation initiative to improve<br />

the pass rate among teachers of color on the<br />

Praxis exam required for teacher certification.<br />

• a “cultural proficiency” program to help<br />

teachers connect their instruction with students’<br />

diverse cultural experiences, with proposed<br />

cultural proficiency standards to be applied in<br />

evaluating school staff.<br />

• a teacher diversity advisory council of<br />

community-based partners that will advise the<br />

District on its teacher diversity initiatives.<br />

Former board president<br />

Rotan E. Lee dies<br />

Rotan E. Lee, who served as president of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s Board of Education and a key<br />

figure in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> school reform in the<br />

1990s, died of heart failure April 24. He was 57.<br />

Lee was appointed by former Mayor W.<br />

Wilson Goode as a member of the Board of<br />

Education in March 1989, and he served as<br />

board president from December<br />

1992 to December 1994. As a<br />

board member and then president,<br />

Lee was known to put in<br />

long hours, including frequent<br />

visits to schools. The 1993 ruling<br />

of a Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court<br />

that students of color were receiving a substandard<br />

education in the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> public<br />

schools was one of the central issues of his<br />

tenure, and racial equity was a topic that he<br />

often addressed with passion.<br />

More recently, Lee had direct involvement<br />

in local school reform efforts during his tenure<br />

as executive vice president and general counsel<br />

for Universal Companies, managers of three<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> schools.<br />

Lee wore many hats: at his death he was a<br />

practicing attorney, a newspaper columnist for<br />

the <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

Tribune and the<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Daily<br />

News, and a radio<br />

host.<br />

A District testimonial<br />

in his<br />

honor presented by<br />

the <strong>School</strong> Reform<br />

Rotan E. Lee<br />

Commission May<br />

10 noted that “when he guided the business of<br />

the <strong>School</strong> District at public meetings, Rotan<br />

E. Lee was apt to reveal his love of literature<br />

by quoting Langston Hughes, and his infatuation<br />

with language by sprinkling the dialogue<br />

with a vocabulary worthy of the most rigorous<br />

college entrance test.”<br />

The testimonial described Lee as “committed<br />

to ensuring that the District served all<br />

students as he would want his own children –<br />

who attended <strong>Philadelphia</strong> public schools – to<br />

be served.”<br />

Contract with K12 for<br />

science curriculum lapses<br />

The <strong>School</strong> Reform Commission allowed<br />

its $3 million contract for elementary school<br />

science materials with K12 Inc. to expire when<br />

it declined to act to renew the contract by a<br />

May 1 deadline.<br />

Controversy about the K12 contract arose<br />

last fall after parents and others protested<br />

broadcast remarks by company co-founder and<br />

shareholder William Bennett about aborting<br />

Black babies that were widely seen as racist. A<br />

proposal to terminate the contract immediately<br />

at that time was defeated by a 3-2 vote of<br />

the SRC despite vociferous community<br />

protests.<br />

District officials say they retain rights to<br />

the curriculum materials. K12, based in Virginia,<br />

has another contract, which expires June<br />

30, to play a management role at the Hunter<br />

<strong>School</strong>.<br />

6 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG SUMMER 2006

Adequate public schools:<br />

how much do they cost?<br />

Pennsylvania’s lowest spending school districts<br />

spend as little as $8,000 per student, while<br />

per pupil expenditures in several of the more<br />

affluent districts in the state exceed $16,000.<br />

In a state with such wide gaps in spending<br />

per pupil, do students in the<br />

low-spending districts get<br />

what they need educationally?<br />

Just how much should<br />

Pennsylvania school systems<br />

spend to ensure that their students<br />

can achieve the standards for proficiency<br />

that have been set by the state?<br />

A number of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and Pennsylvania<br />

advocacy organizations are raising these<br />

questions and suggesting that it is time for the<br />

state to answer them by conducting what they<br />

call a "costing-out” or “adequacy” study. Such<br />

a study would first aim to determine what supports<br />

need to be in place in order for schools<br />

to enable their students to meet the state’s learning<br />

standards, and then would calculate the<br />

school funding level needed to provide those<br />

necessary supports and resources to schools.<br />

The idea of costing out is not a new one,<br />

according to its proponents, which include<br />

Good <strong>School</strong>s Pennsylvania, the Education<br />

Law Center, and the Education Policy and<br />

ACTIVISM<br />

Around<br />

THE CITY<br />

Leadership Center (EPLC). They report that<br />

costing out studies have been conducted or are<br />

underway in 38 states to help align funding levels<br />

with the education standards and goals in<br />

the state.<br />

While Pennsylvania is not yet one of those<br />

states, the State Board of Education here has<br />

appointed a panel to explore the idea. In addition,<br />

a resolution has been proposed<br />

in the legislature that<br />

would direct a statewide study<br />

looking at what resources are<br />

demanded by the state’s academic<br />

standards, including needs<br />

resulting from factors such as poverty, limited<br />

English proficiency, and disabilities.<br />

According to EPLC president Ron Cowell,<br />

a costing-out study is a “logical next step” for<br />

state policymakers who have established academic<br />

standards and proficiency expectations<br />

for students.<br />

For more information about work towards<br />

a costing-out study, contact Good <strong>School</strong>s<br />

Pennsylvania at info@goodschoolspa.org or<br />

866-720-4086.<br />

Youth United for Change<br />

presents plan for Olney<br />

Youth United for Change (YUC), a student<br />

Photo: Youth United for Change<br />

At a Youth United for Change press conference and school tour with State Sen. Shirley Kitchen<br />

(left) on February 28 outside Olney High <strong>School</strong>, 11th grader Rasheeda Enoch (center) delivers<br />

speech calling for the conversion of Olney to small schools.<br />

organization with a history of education reform<br />

activism, presented their plan for dividing troubled<br />

Olney High <strong>School</strong> into six small schools<br />

at a community meeting in April. Last fall, the<br />

school was divided into two separate schools<br />

by constructing a wall; each opened the school<br />

year with about 1000 students.<br />

YUC’s plan, presented by students from<br />

the group’s Olney chapter, is based on published<br />

research that suggests that to realize<br />

major academic and behavioral gains, small<br />

schools should be no larger than 400 students.<br />

The proposal calls for the partition of the<br />

existing building into four autonomous schools<br />

with a second building holding two additional<br />

schools. The schools would share some facilities<br />

and have joint extracurricular activities.<br />

Along with a three-year history of pressing<br />

for small schools at Olney, YUC has led a community-based<br />

effort to implement a small<br />

school model at Kensington High <strong>School</strong>.<br />

Students have visited successful small<br />

schools in New York and Oakland and have<br />

interviewed educators with expertise in this<br />

area.<br />

A “design team” of community members<br />

See “Activism” on p. 8<br />

SUMMER 2006 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG 7

Activism<br />

continued from p. 7<br />

and parents is being formed to further develop<br />

and promote the plan for Olney. <strong>School</strong> District<br />

officials have indicated that they are open<br />

to proposals for improving the school, which<br />

continues to suffer from high absenteeism, a<br />

high dropout rate, and low test scores.<br />

But District CEO Paul Vallas said in a May<br />

interview that there are no plans to create more<br />

than two schools at Olney. He said student<br />

enrollment at the two existing schools will be<br />

reduced significantly due to a new charter high<br />

school opening in the neighborhood next year.<br />

Vallas also said the District lacks the funds to<br />

construct a new Olney High <strong>School</strong> – a project<br />

that had been included in the District’s<br />

two most recent annual capital budget plans.<br />

YUC member Anthony Warrick, an 11th<br />

grader at Olney, said YUC’s plan can be<br />

achieved with “a commitment from the community<br />

to create small schools at Olney and<br />

money from the <strong>School</strong> District.”<br />

For more information on YUC’s work at<br />

Olney High <strong>School</strong>, call 215-423-9588.<br />

Fighting deportations<br />

of immigrant parents<br />

“Danny” (name changed for privacy), a<br />

first-grader at a <strong>Philadelphia</strong> charter school,<br />

was home the night immigration agents came<br />

to pick up his father for deportation to Indonesia.<br />

According to Danny’s mother, the immigration<br />

agents told his father to say goodbye<br />

to his son because he would never see him<br />

again. His mother said the incident has traumatized<br />

Danny, who is coping not only with<br />

the loss of his father but also with the fear of<br />

an uncertain future.<br />

As Immigrations and Customs Enforcement<br />

(ICE) ramps up deportations locally, a<br />

number of schools, community organizations,<br />

and coalitions are strategizing to fight against<br />

what activists call “cruel” and “inhumane”<br />

practices.<br />

Independence Charter <strong>School</strong> and the Folk<br />

Arts Cultural Treasures Charter <strong>School</strong> have<br />

sponsored letter-writing campaigns on behalf<br />

of school families threatened with deportation.<br />

Immigrant rights advocacy groups formed<br />

the Day Without An Immigrant Coalition,<br />

which lists family unity as a central platform<br />

of immigration reform. The group has sponsored<br />

local rallies and educational forums,<br />

which have drawn tens of thousands of supporters.<br />

According to the Urban Institute, as many<br />

as one in 10 American families have at least<br />

one parent as an undocumented immigrant.<br />

Mary Yee, director of the <strong>School</strong> District’s<br />

Office of Family Engagement and Language<br />

Equity Services, said the District doesn’t have<br />

firm figures on the number of local children<br />

potentially affected by deportation, but estimates<br />

that 1,000 to 4,000 students could be<br />

impacted.<br />

Ellen Somekawa, executive director of<br />

Asian Americans United, said that organization<br />

is supporting the “Justice for Jiang Zhen<br />

Xing Campaign.” Jiang Zhen Xing, the mother<br />

of two elementary-aged children, miscarried<br />

her second-trimester twins following a<br />

deportation attempt where she said she was<br />

denied adequate food, water and requested<br />

medical attention for hours.<br />

Somekawa noted, “Many of us are not prepared<br />

to handle the brutality of this system,<br />

but clearly it’s something we need to figure<br />

out, especially as immigration rules become<br />

harsher,”<br />

At the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter<br />

<strong>School</strong>, principal Deborah Wei said the letter-writing<br />

campaign helped children engage<br />

in a discussion about human rights at a basic<br />

level – the right of a family to remain together.<br />

“The children’s questions are quite simple,”<br />

Wei said. “But no one can answer them."<br />

8 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG SUMMER 2006

After period of steady funding growth, budget tightens<br />

continued from p. 1<br />

Despite the recent growth spurt in funding,<br />

the <strong>School</strong> District’s per pupil funding level<br />

still consistently ranks near the bottom among<br />

the 63 school districts in the five-county region.<br />

That spurt was based in part on an increment<br />

in both state and city funding resulting from<br />

the negotiated state takeover in 2001-02, as<br />

well as a $300 million deficit financing move<br />

by the city, which provided a financial cushion<br />

that has now been largely depleted.<br />

A relatively poor school system, the District<br />

still has difficulty trimming its budget<br />

without jeopardizing vital personnel and programs,<br />

as protests by parents and others this<br />

spring have highlighted. The District’s $2.04<br />

billion budget plan for 2006-07 requires cuts<br />

to balance out rising costs in areas such as<br />

employee benefits, debt service, and charter<br />

schools that together far exceed any antici-<br />

pated increases in revenues.<br />

District officials say their projections are<br />

realistic but acknowledge uncertainty about<br />

how next year’s budget will end up. Even<br />

assuming that the state legislature fully endorses<br />

the significant funding increases provided<br />

in Governor Rendell’s state budget proposal,<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> must make reductions in a variety<br />

of programs, including a 5 percent acrossthe-board<br />

cut to school-based budgets.<br />

SRC Chairman James Nevels noted that<br />

cuts have affected every school. “We are in a<br />

budgetary crunch,” he said.<br />

“This budget – and really our last two budgets<br />

have stretched me,” said CEO Paul Vallas,<br />

who acknowledged his inability to add art<br />

and music teachers and added that “it has<br />

impacted my ability to do class size reduction.”<br />

Ann Listerud, a parent at the Powel <strong>School</strong><br />

in West <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, characterized the situa-<br />

tion as “a school district in crisis.” Powel parents<br />

have been demanding a commitment from<br />

the District to restore budget cuts at the school<br />

that they say amount to $190,000.<br />

“We know something is seriously wrong<br />

when the District has to make drastic cuts to<br />

an excellent performing school with a 40-year<br />

history,” said Listerud, who serves on Powel’s<br />

school council. “What further disturbs us are<br />

the stories we are hearing from our parentgrandparent<br />

population who work in schools<br />

around the District – stories about SSAs,<br />

ESOL, Special Ed, music, drama and classroom<br />

teachers, all being let go.”<br />

Both <strong>School</strong> District officials and education<br />

advocates have turned their attention to<br />

the state budget process, which often drags out<br />

till the end of June.<br />

One issue is a $25 million annual line item<br />

in the state budget earmarked to support privately<br />

managed schools in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> that<br />

was deleted by the state House. District and<br />

local officials say they still hope the funds will<br />

be restored.<br />

“If we lose that $25 million, I’m not going<br />

to cut afterschool and summer school programs<br />

in order to finance the EMOs [education management<br />

organizations],” Vallas said.<br />

Meanwhile, a newly formed coalition of 10<br />

Pennsylvania organizations is calling on candidates<br />

for state office to pledge to increase<br />

the state share of public education costs to 60<br />

percent from the current 36 percent.<br />

The “Statewide Coalition to Close the<br />

Gap,” which is highlighting what it calls “gross<br />

disparities” in spending among districts in the<br />

state, compared spending per pupil in <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

to the average spent by the top one-fifth<br />

of school districts in the state. They found that<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s spending lags this group of highperforming<br />

school districts by more than<br />

$2,700 per pupil, according to Michael<br />

Churchill of the <strong>Public</strong> Interest Law Center of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>.<br />

SUMMER 2006 PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC SCHOOL NOTEBOOK • WWW.THENOTEBOOK.ORG 9

Maestros de arte y música a tiempo completo<br />

continúa de la p. 1<br />

a tiempo completo de arte (vea la lista, página<br />

14). Estos números son mayores que los de<br />

hace cuatro años, cuando la organización<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Citizens for Children and Youth<br />

(Ciudadanos de Filadelfia para los Niños y la<br />

Juventud) produjo un informe sobre la reducción<br />

en el número de maestros de arte y de<br />

música justo antes de que Vallas tomara las<br />

riendas del Distrito. Entonces, 82 escuelas no<br />

tenían maestros a tiempo completo de arte, y<br />

83 no tenían maestros a tiempo completo de<br />

música.<br />

Desde el 2002-03, el número de maestros<br />

de arte en el Distrito se ha reducido en un 16<br />

por ciento, en comparación a la reducción de<br />

toda la fuerza laboral de maestros del 5 por<br />

ciento. Para los maestros de música, la reducción<br />

ha sido aproximadamente del 7 por ciento.<br />

Las escuelas con mayor tendencia a no<br />

tener maestros de música y de arte son las<br />

escuelas racialmente aisladas, en las que más<br />

del 90 por ciento de los estudiantes no son<br />

blancos. Setenta por ciento de las 66 escuelas<br />

que no tienen maestros ni de arte ni de música<br />

son racialmente aisladas, en comparación<br />

con el 62 por ciento de las escuelas del<br />

Distrito.<br />

La decisión de<br />

contratar o retener<br />

los maestros recae<br />

sobre los principales.<br />

La tasa de pobreza promedio en las escuelas<br />

que no tienen maestros de arte ni de música<br />

es 79 por ciento, igual a la tasa del Distrito.<br />

Sin embargo, unas pocas escuelas magnet<br />

o escuelas en el Noreste que tienen los porcentaje<br />

más elevados de estudiantes de clase<br />

media, tampoco tienen maestros de arte ni de<br />

música.<br />

La decisión de contratar o retener los<br />

maestros recae sobre los principales, quienes<br />

tienen que manejar las exigencias de los<br />

exámenes de aptitud y todo tipo de peticiones<br />

en base a los fondos disponibles. La mayoría<br />

de las escuelas han visto una reducción en sus<br />

presupuestos y en los maestros asignados<br />

durante los últimos años, a la vez que se les<br />

responsabiliza cada vez más por el progreso<br />

de los estudiantes.<br />

Vallas dijo que el aumento en escuelas sin<br />

música y sin arte se debe en gran parte a que<br />

las organizaciones de administración educativa<br />

(EMO por sus siglas en inglés) decidieron<br />

no seguir ofreciendo esas materias, y no por<br />

opción de las escuelas administradas por el<br />

Distrito. En 2002 la SRC le transfirió más de<br />

40 escuelas a las EMO como parte de una<br />

estrategia de reforma mediante privatización.<br />

Otro factor en el aumento en el número de<br />

escuelas sin arte ni música, dijo Vallas, ha sido<br />

la creación de más de una docena de nuevas<br />

escuelas superiores pequeñas, cuyos presupuestos<br />

no pueden afrontar una amplia diversidad<br />

de ofrecimientos.<br />

“Lo ideal sería que cada escuela tuviese 17<br />

o 18 estudiantes por salón, un maestro de arte,<br />

uno de música y una bibliotecaria,” dijo<br />

Vallas. “Pero los fondos no lo permiten. Estamos<br />

haciendo todo lo que podemos con los<br />

recursos que tenemos.”<br />

La Ley Que Ningún Niño Quede Atrás<br />

(NCLB, por sus siglas en inglés) requiere que<br />

las escuelas mejoren las puntuaciones en los<br />

exámenes de lectura y matemáticas todos los<br />

años. Aunque la mayoría de las escuelas de<br />

la ciudad no han cumplido con las metas de la<br />

NCLB, las puntuaciones de los exámenes han<br />

estado mejorando en términos generales,<br />

especialmente en los grados más bajos.<br />

Esto no es de mucho consuelo para los<br />

maestros de arte y de música, que están acostumbrados<br />

a desarrollar la creatividad de los<br />

niños a diario y a encontrar y cultivar talento<br />

en algunos de los vecindarios más pobres<br />

de la ciudad. A los niños más necesitados se<br />

les podría estar negando la instrucción de arte<br />

y de música aún cuando está disponible<br />

porque tienen que dedicarle más tiempo a la<br />

lectura y a la matemática, dicen ellos.<br />

“Una de las omisiones más graves en la<br />

educación de los jóvenes de Filadelfia es el<br />

hecho vergonzoso de que la mayoría de<br />

nuestros niños de bajos ingresos no tienen el<br />

beneficio de contar con arte o música en el<br />

programa diario escolar, en vez de sólo<br />

‘después de la escuela’ o como un ‘enriquecimiento<br />

ocasional’, dijo Jo-Anna Moore,<br />

coordinadora de educación en arte en la<br />

Escuela de Arte Tyler de la Temple University.<br />

“En realidad es un problema que se<br />

reduce a ingresos o clase, porque los niños<br />

que pudieran beneficiarse drásticamente de<br />

las oportunidades educativas más ricas y más<br />

diversas son los que menos las tienen. Definitivamente<br />

sabemos que esto está mal.”<br />

Lynne Horoschak, su colega en el Moore<br />

College of Art que dedicó 36 años en el<br />

Distrito, dijo que el enfoque en las destrezas<br />

de lectura y matemáticas solamente ha logrado<br />

desplazar el aprendizaje inventivo y basado<br />

en proyectos.<br />

“Ya no existe la habilidad de integrar,”<br />

dijo Horoschak. “Todo el tiempo se necesita<br />

para las artes de lectura/lenguage y las<br />

matemáticas.” Proyectos como “pedirle a los<br />

estudiantes que escriban una obra teatral sobre<br />

el Renacimiento” ya no se usan porque el<br />

enfoque está en la preparación para el<br />

examen. Ella dijo que cuando los maestros<br />

veteranos de arte se retiran, a menudo no se<br />

reemplazan y los programas que fomentaron<br />

por años simplemente se desvanecen.<br />

Dennis Creedon, el administrador para las<br />

artes creativas e interpretativas del Distrito,<br />

reconoció que la ley Que Ningún Niño Quede<br />

Atrás ha alterado las prioridades de muchos<br />

principales, quienes podrían optar por contratar<br />

a un maestro adicional de lectura en<br />

lugar de reemplazar a un maestro de arte o<br />

de música que se retire.<br />

“El arte, al igual que los estudios sociales,<br />

no es un tema de examen, y por eso lo que se<br />

enseña es lo del examen,” dijo. Añadió que<br />

los principales y los padres a menudo no<br />

entienden los beneficios académicos que la<br />

enseñanza de arte y de música puede tener.<br />

Escuela invierte $2 millones<br />

en nueva área de artes<br />

Resistiendo la tendencia nacional de reducir la educación de arte en las escuelas, la<br />

Escuela Superior Chárter Nueva Esperanza – respaldada financieramente por Nueva<br />

Esperanza Inc., la organización comunitaria que la fundó – está invirtiendo $2 millones para<br />

añadir 20,000 pies cuadrados al área de la escuela en Hunting Park que actualmente se<br />

dedica al estudio del arte. El proyecto añadirá a la escuela de 600 estudiantes un taller para<br />

cerámicas, un cuarto oscuro, un salón de artes visuales, un auditorio, un salón de cinematografía<br />

y una galería de arte.<br />