Isabela eps:Layout 1 - Advanced Conservation Strategies

Isabela eps:Layout 1 - Advanced Conservation Strategies

Isabela eps:Layout 1 - Advanced Conservation Strategies

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

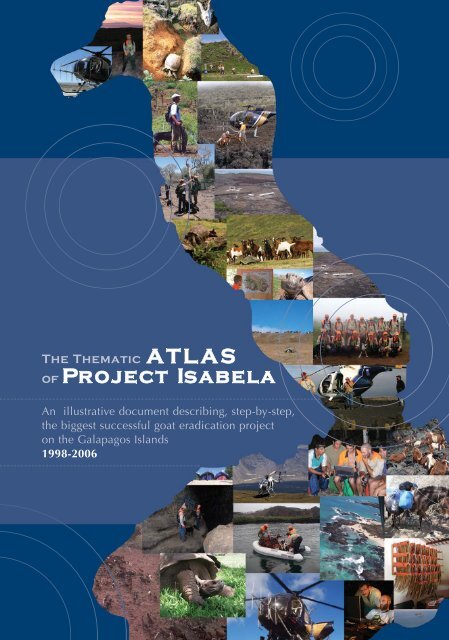

The Thematic ATLAS<br />

of Project <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

An illustrative document describing, step-by-step,<br />

the biggest successful goat eradication project<br />

on the Galapagos Islands<br />

1998-2006

CREDITS<br />

Atlas coordinator: Christian Lavoie<br />

Editors: Felipe Cruz • Sylvia Harcourt • Christian Lavoie<br />

Translation: Sylvia Harcourt<br />

Graphic design: Marycarmen Moya<br />

Original texts by: Karl Campbell • Víctor Carrion • Felipe Cruz • Christian Lavoie<br />

Data analysis: Karl Campbell • Josh Donlan • Christian Lavoie<br />

Cartography: Christian Lavoie<br />

Pictures: Project <strong>Isabela</strong> •David Jiménez •Heidi Snell •Carolina Larrea •Tui De Roy•Matts Wedin •Richard Wollocombe<br />

Other participants: Rachel Atkinson • Wilson Cabrera • Aleyda Puente<br />

Printing: Impresora Flores<br />

"We would like to acknowledge the vital support of the following foundations and individuals whose foresight and participation<br />

provided critical funding throughout Project <strong>Isabela</strong>:<br />

Galapagos Conservancy (formerly Charles Darwin Foundation Inc)<br />

Galapagos <strong>Conservation</strong> Trust<br />

Frankfurt Zoological Society<br />

Swiss Association of Friends of the Galapagos Islands<br />

Friends of Galapagos Netherlands<br />

The Prospect Hill Foundation<br />

The Mars Foundation<br />

Steven Merrill<br />

The Stewart Foundation<br />

The Dumke Foundation<br />

Charles and Judy Tate<br />

Kelly and Sandy Harcourt<br />

Greg and Elizabeth Lutz/The Lutz Foundation<br />

Mr and Mrs Christopher Holdsworth Hunt<br />

Mr Peter Hutley<br />

Mr and Mrs James Teacher<br />

Project ECU/00/G31/GEF-UNDP<br />

We are also deeply grateful to the many individuals whose private support and encouragement sustained this extraordinary project to its<br />

successful conclusion"<br />

Finally our special thanks to the truly dedicated “Project <strong>Isabela</strong> Team”<br />

The Thematic Atlas of Project <strong>Isabela</strong> is dedicated to Sven Lindblad,<br />

Lindblad Expeditions and Galapagos <strong>Conservation</strong> Fund,<br />

as a token of our gratitude for their continuos<br />

support to Project <strong>Isabela</strong>.<br />

The Charles Darwin Foundation operates the Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island, Galapagos, Ecuador.<br />

CDF is an international not-for-profit association (Association Internationale Sans But Lucratif, AISBL), registered in Belgium under the<br />

number 371359 and subject to Belgian law. The address in Belgium is Avenue Louise 50, 1050, Brussels.<br />

CONTENTS<br />

The Project <strong>Isabela</strong> 5<br />

Feral Goats in Galapagos 9<br />

Management & Strategy 13<br />

Results & Effort 23<br />

Efficiency & Costs 37<br />

Confirming Eradication & Ecological Extinction 49<br />

Benefits 55<br />

Publications by Project <strong>Isabela</strong> 58

Project <strong>Isabela</strong> vs Previous Projects<br />

ISLAND SIZE (ha) COST<br />

(2006 US$)<br />

RAOUL*<br />

New Zealand<br />

PINTA<br />

Galapagos, Ecuador<br />

SANTIAGO<br />

Galapagos, Ecuador<br />

ISABELA<br />

Galapagos, Ecuador<br />

2,943 ha<br />

5,940 ha<br />

58,465 ha<br />

458,812 ha<br />

$<br />

$ 3,473,068<br />

$<br />

$ 83,891<br />

$<br />

$ 5,483,373<br />

$<br />

$ 3,009,529<br />

ISLAND COST/ha<br />

(2006 US$)<br />

RAOUL*<br />

Making the most of every $<br />

COST / ANIMAL<br />

(2006 US$)<br />

2 3<br />

New Zealand<br />

PINTA<br />

Galapagos, Ecuador<br />

SANTIAGO<br />

Galapagos, Ecuador<br />

ISABELA<br />

Galapagos, Ecuador<br />

$<br />

1,180.11 $/ha<br />

$<br />

14.12 $/ha<br />

$<br />

93.79 $/ha<br />

6.56 $/ha<br />

* Parkes, J. P. (1990). Feral goat control in New Zealand. Biological <strong>Conservation</strong> 54, 335-348.<br />

$<br />

$<br />

$<br />

504.95 $/goat<br />

1,290.63 $/goat<br />

$<br />

61.29 $/goat<br />

$<br />

47.91 $/goat

THE PROJECT ISABELA<br />

What is PI?<br />

THE PROJECT ISABELA<br />

Foreword from Project leaders 6<br />

The Project 7<br />

5

THE PROJECT ISABELA<br />

6<br />

Foreword from Project Leaders<br />

“The necessity to conserve Galapagos, Natural World Heritage” “The PI restoration plan called for helicopters to be used as shooting<br />

platforms, species-specific trained dogs, high quality hunters<br />

and Judas goats, and was budgeted at $8.5 million”<br />

Felipe Cruz, Charles Darwin Foundation, Co-Director of Project <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

The development and successful expansion of our species has produced the secondary effect of causing the extinction of<br />

hundreds of species, an extinction which has been unnaturally rapid. All modern vertebrate extinctions have probably<br />

been caused by man. On oceanic islands the situation is particularly delicate. These sites represent only 7% of the earth’s<br />

surface, and less than 10% of bird species are present on islands, but more than 80% of the birds which have gone extinct<br />

were island forms. Of the 396 species of birds cited by IUCN as threatened, 236 (60%) are island endemics.<br />

There are three principle causes which explain this catastrophic phenomenon 1) hunting and/or over exploitation (as in<br />

the case of the land tortoises); 2) the impact of introduced species and 3) habitat destruction.<br />

The rate of extinctions ke<strong>eps</strong> speeding up. In conservation biology one no longer talks about avoiding the extinction of<br />

species, but now it is a discussion as to which species can be saved. We are rather like a collective Noah, deciding with<br />

a biblical coldness which life forms will be able to accompany us on our new journey in the Ark. The world state<br />

continues to get worse, but in Galapagos we still have the opportunity to reverse this trend because the human presence<br />

is fairly recent; because the impacts of the invasive species are reversible; because here we still maintain 95% of the<br />

native and endemic biodiversity; and, because of geographical isolation, we can help to protect the area with strict<br />

processes which make the arrival of new invasive species more difficult.<br />

Throughout the world many plant and animal species are at a level of threat which has not been registered at any<br />

previous moment in history. It is therefore not at all surprising that protection of the biodiversity is one of the biggest<br />

priorities for conservation on a world level. In this context Project <strong>Isabela</strong> is an example of restoration of ecosystems on<br />

a scale never carried out before. Until now, the conservation world thought it impossible to work on this scale. We have<br />

achieved, in record time, the reversal of the degradation processes that were occurring on <strong>Isabela</strong> and Santiago,<br />

improving by 60% the conservation status of the native and endemic species of Galapagos. Through the combining of<br />

effort and knowledge and with the strengthening of local capacities, we consider that this is pioneer work and we are<br />

sure that the possibilities of replicating it will be of help on a world scale.<br />

We can not afford to lose even one species of our world heritage without in some manner impoverishing our society and<br />

that of future generations. Probably the experts in conservation do agree that Project <strong>Isabela</strong> achieved the recovery of the<br />

habitat and the protection of the species in these areas, on a scale never attempted before, through an initiative which<br />

combined previous experiences and developed new forms of confronting problems. Even though the initial costs may<br />

have seemed high, the final benefits are greater than the investment.<br />

Our world heritage is not an acquired right, but an undeniable inheritance for future generations.<br />

Victor Carrion, Galapagos National Park, Co-Director of Project <strong>Isabela</strong>, (Responsible for the Area of<br />

Control and Eradication of Introduced Species in GNP).<br />

The Galapagos Islands are located approximately 1,000 kms from the continent, and were formed by volcanic eruptions.<br />

They have a land surface of 7,970 km 2 and a Marine Reserve of approximately 138,000 km 2 , and maintain an important<br />

level of biological diversity and endemism. Of all the species identified in Galapagos (more than 5,000) about 1,900 are<br />

endemic and 74 are threatened. The animal species most representative of the islands are the Darwin finches, the Galapagos<br />

penguin, the flightless cormorant, giant tortoises, marine and terrestrial iguanas and amongst the plants, the Scalesia and<br />

Miconia. 95% of the original biodiversity has still been maintained. The extinctions of mammals (various species of endemic<br />

rice rats) which have occurred have been due principally to the effects of species (such as the black rat) introduced by man.<br />

Of the land surface, more than 96% is protected by the State, and this was declared a National Park in 1959. In 1978 the<br />

Park was included in the list of World Heritage Sites of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural<br />

Organization); in 1984 it became part of the network of the World Biosphere Reserves in the UNESCO program, Man and<br />

the Biosphere and in 1998 UNESCO declared the Marine Reserve of Galapagos as a protected area and World Heritage Site.<br />

This Reserve covers all the interior waters as well as extending to 40 miles around the islands measured from the most extreme<br />

points (base line).<br />

The arrival of man in Galapagos provoked the beginning of the progressive deterioration of the natural environment of the<br />

islands, particularly because of the deliberate introduction of species of plants and animals for subsistence farming in these<br />

“inhospitable” islands. The surroundings which these species found on their arrival was such that they could colonize in an<br />

accelerated manner, escaping man’s control and becoming from then on, one of the worst threats to the island ecosystems.<br />

The efforts which are now necessary to reverse these impacts keep increasing. In some cases the future is very bright but in<br />

others it is very uncertain as we still do not have mechanisms and techniques to cause the drastic reductions necessary in the<br />

populations of invasive species such as rats, cats, anis, and the plants such as blackberry, guava, cinchona and a host of<br />

invertebrate species.<br />

This Document; Karl Campbell, Christian Lavoie & PI Team<br />

The Project<br />

The Project <strong>Isabela</strong> Atlas is an illustrative document that provides a step-by-step overview of Project <strong>Isabela</strong>’s activities and<br />

achievements. The primary role of this Atlas is to provide a visual and easy-to-read outline of the strategy, methods, results<br />

and magnitude of the eradication challenges.<br />

Managing a large intensive project with different methods being employed sequentially and others simultaneously was<br />

facilitated by a geographical information system (GIS), a system that was designed and implemented for managing most of<br />

the spatial data. This, along with a database for managing effort and kill data allowed information to be accessed in a timely<br />

manner by managers in the field, while also forming the basis for further analyses and publications. The Atlas shows many of<br />

the visual tools used by managers and hunters on a daily basis to facilitate their activities. These tools increased the efficacy<br />

of the project and dramatically improved our ability to achieve concrete results.<br />

The Atlas’s intended audience is broad, from the general public to conservation practitioners and eradication specialists.<br />

Many of the examples included here on how we conducted various aspects of our work will not be presented visually in any<br />

other publication. We’ve tried to make this document short and easy reading, informative, attractive and interesting. We hope<br />

that by the time you turn the last page you will feel as excited about restoring islands as we are.<br />

PI Background<br />

Eliecer Cruz and Robert Bensted-Smith, directors of the Galapagos National Park Service (GNPS) and the Charles Darwin<br />

Foundation (CDF) conceived Project <strong>Isabela</strong> as a bi-institutional initiative. Linda Cayot, then head of Vertebrates at the CDF<br />

became the first bi-institutional leader of the Project. With this new position, Linda also inherited the ongoing Santiago pig<br />

eradication project. In 1996 Brian Bell visited from New Zealand and put together a proposal for eradicating goats from northern<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>. Shocked by the $5 million price-tag, it was thought wise to invest in a more complete revision and bring in a range of<br />

world renowned experts to develop a restoration plan. In September 1997, sixteen experts attended a workshop in Galapagos<br />

and drafted a plan. The plan called for helicopters to be used as shooting platforms, specialist dogs, high quality hunters and<br />

Judas goats, and was budgeted at $8.5 million. The underlying philosophy was to bring all the best methods, techniques and<br />

tools from around the world into one project. We invested time and money into improving methods and tools that were not<br />

efficient or yet being applied. Improvements in Judas goat methods and the application of GIS to facilitate management are<br />

prime examples. Less than a year after the workshop Linda left the Galapagos; Marc Patry and Felipe Cruz took over and Karl<br />

Campbell came in as volunteer for his second tour. Two years later, as Marc left, Felipe along with Victor Carrion became heads<br />

of PI, while Karl became field operations manager and Christian Lavoie joined the team as the GIS specialist.<br />

Santiago Pig Eradication<br />

Pigs raided giant tortoise and sea turtle nests, preyed upon Galapagos rails and their eggs and altered vegetation for over 150<br />

years on Santiago. A revised campaign utilizing systematic hunting of zones by hunters and dogs and the strategic use of<br />

toxic baits ended a 30 year campaign. The last pig was removed in November 2000. In total, over 18,000 pigs were removed<br />

during the campaign. Santiago is the largest island in the world where feral pigs have been eradicated, the second largest<br />

island is only about half its size. Today, turtle and tortoise eggs and hatchlings, nesting seabirds such as Galapagos petrels,<br />

and many plant species suffer no pig predation. Galapagos rails have dramatically increased in numbers, with Santiago now<br />

being the strong-hold for this charismatic endemic species (read about the Galapagos Rail on page 57).<br />

Pinta Goat Eradication<br />

Within the plan to eradicate goats from <strong>Isabela</strong> was a trial to gain experience in the Judas goat method while eradicating<br />

goats from Pinta Island. Judas goats (JG) are goats that are captured, fitted with radio telemetry collars and released. As goats<br />

are gregarious, JG´s search out and associate with other goats. They can then be tracked down and any associated feral goats<br />

can be removed. This method is used when goats are at very low densities, increasing the efficiency with which feral goats<br />

can be detected by reducing search time.<br />

Goats were introduced to Pinta in the 1950s and by the 1970s had devastated the island’s native vegetation. Goats were<br />

removed from Pinta Island after a 30-year eradication campaign, the largest removal of an insular goat population using<br />

ground-based methods. Over 41,000 goats were removed during the initial hunting effort (1971–82). In the following decade<br />

the island was twice wrongly declared free of goats. During this period, the island was visited irregularly but no monitoring<br />

program was implemented. A revised campaign over 1999–2003, which included improved hunting techniques, Judas goats<br />

and monitoring, removed the final goats from the island.<br />

7<br />

THE PROJECT ISABELA

FERAL GOATS IN GALAPAGOS<br />

Feral Goats in Galapagos<br />

FERAL GOATS IN GALAPAGOS<br />

Capra hircus in Galapagos 10<br />

PI targeted islands 11<br />

9

FERAL GOATS<br />

IN GALAPAGOS<br />

10<br />

Capra hircus in Galapagos<br />

“Nearly half of all terrestrial life forms in Galapagos<br />

are found nowhere else on earth”<br />

Introduced mammals are major drivers of extinction. Feral goats (Capra hircus) are particularly devastating to island<br />

ecosystems, causing direct and indirect impacts through overgrazing, which often results in ecosystem degradation and<br />

biodiversity loss. Goats and donkeys are the primary threat to Galapagos’ most endangered plants, and are believed<br />

responsible for one plant extinction, an endemic from Santiago. Goats convert forest to grassland by stopping regeneration<br />

and felling trees or girdling and killing them with their horns. In this way they eliminate entire forests and ecosystems from<br />

islands they inhabit. Endemic birds, reptiles and other animals that rely on this habitat disappear; if these species are<br />

restricted to those areas they are lost forever. As seen on Santiago, many palatable endemic plant species are often reduced to<br />

individuals hanging on in inaccessible bluffs. Exclosures provide seed banks for safe keeping of these severely reduced<br />

populations, but the threats must be removed for recovery to<br />

occur.<br />

Goat menace!<br />

Removing goat populations from islands is a powerful conservation tool to prevent extinctions and restore ecosystems. Goats<br />

have been eradicated successfully from 120 islands worldwide. With newly developed technology and techniques, island<br />

size is perhaps no longer a limiting factor in the successful removal of introduced goat populations. Furthermore, the use of<br />

global positioning systems (GPS), geographic information systems, aerial hunting by helicopter, specialized hunting dogs, and<br />

Judas goats have dramatically increased efficiency and significantly reduced the duration of eradication campaigns.<br />

Intensive monitoring programs are also critical for successful eradications. Eradication removes the entire population of a<br />

given species from an area, compared to control efforts where a percentage of the population will be removed in perpetuity.<br />

Eradication offers a permanent solution with a once-off investment, and given the clear biodiversity benefits, the introduced<br />

goat populations should be permanently removed.<br />

Because of the presence of humans with domestic goat populations on large islands, future island conservation actions will<br />

require eradication programs that involve local island inhabitants in a collaborative approach with biologists, sociologists,<br />

and educators.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Worldwide # of islands where goats have been eradicated: 120<br />

• Range size of these islands: 1 to 132,000 ha<br />

• Cumulated area of these islands: 600,000 ha<br />

• Luxembourg = 50% of PI targeted islands<br />

• Monaco = 0,04 % of PI targeted islands<br />

• PI targeted islands = 20% of Massachusetts State<br />

C. Azul<br />

1,625 m.<br />

TOPOGRAFIC PROFIL<br />

Topographic profile of <strong>Isabela</strong> Island<br />

S. Negra<br />

1,100 m.<br />

PI targeted islands<br />

Pushing the limits to a total new scale<br />

Alcedo<br />

1,150 m.<br />

Darwin<br />

1,425 m.<br />

Wolf<br />

1,707 m.<br />

Ecuador<br />

875 m.<br />

FERAL GOATS<br />

IN GALAPAGOS<br />

11

MANAGEMENT & STRATEGY<br />

How it has been done<br />

MANAGEMENT & STRATEGY<br />

Eradication methods 14<br />

Chronological strategy 16<br />

Ground hunting management 18<br />

Aerial hunting management 19<br />

Judas goats management 20<br />

13

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

14<br />

Eradication methods<br />

“On large islands a range of methods used sequentially<br />

and simultaneously are required to put all animals at risk”<br />

Strategic use of methods<br />

Throughout all our eradication work we followed some simple rules. Where possible as close to 100 % of the animals were<br />

removed on their first encounter, reducing the possibility that survivors learn from their exposure to a certain hunting<br />

method. We studied the vegetation type, topography and goat densities; and hunters’ efforts revolved heavily around<br />

techniques to minimize escapes. For example, on Santiago mustering was used in the highlands in the first months as this<br />

was the only practical method by which herds of thousands of animals could be removed with near zero escapes. In<br />

eradication, efficacy (being efficient and effective) is a combination of minimizing cost per kill and maximizing the ratio of<br />

goats killed to escapes. Each method is suited to different terrain, vegetation type and goat densities. This creates a hierarchy<br />

of methods that can be used sequentially. The development of wary animals to any one method requires a change in<br />

methods to place those animals at risk. In various situations it is also highly<br />

advantageous to use different methods simultaneously.<br />

Aerial hunting<br />

Landscape or vegetation type offer refuge for goats from one or more<br />

methods; however no vegetation or terrain type provides refuge for goats from<br />

all methods. On Santiago goats found refuge from ground hunters with dogs<br />

in lava fields, a place where aerial hunting excels. Conversely, goats found<br />

refuge from helicopters by remaining motionless under vegetation and by<br />

hiding under thick vegetation and in caves; these areas and tactics then made<br />

goats vulnerable to ground hunters with dogs. On a large scale and on<br />

complex islands, a refuge will likely exist for most methods. As such, on large<br />

islands a range of methods used sequentially and simultaneously is required<br />

to put all animals at risk.<br />

Ground based mustering and corrals<br />

In order to channel goats into corrals, we used netting strung out in large<br />

“wings” up to several kilometers in length. This method was developed to<br />

facilitate the removal of vast herds of goats that could not effectively be<br />

removed by other means without significant numbers of escapes. Prior to the<br />

arrival of helicopters this method was fundamental as an initial knock-down<br />

tool, and was very cost-effective.<br />

In the 1970s New Zealanders began using helicopters intensively as aerial shooting<br />

platforms and for recovering deer carcasses for a demanding European market. Aerial<br />

shooting is now practiced extensively in Australia and New Zealand to control feral<br />

animals cost-effectively and on a large scale. Contrary to common belief this method is<br />

actually endorsed by animal welfare organizations as the most humane method of<br />

removing feral goats in rough terrain. It is highly effective in sparsely vegetated areas or<br />

areas with trees with open canopy; the majority of <strong>Isabela</strong> and large tracts of Santiago<br />

fit this description. Aerial shooting is cost-effective at high and low animal densities and<br />

allows for the rapid coverage of large areas.<br />

Ground hunting<br />

Traditional hunting, or, as we’ve dubbed it, free hunting, involves individual or pairs of<br />

hunters with or without their dogs hunting freely within a zone. This allows hunters to<br />

concentrate their efforts and use various hunting tactics in areas where goats are frequent,<br />

such as hill-tops, rocky ridges, cliffs, craters and lines of caves. This method<br />

is most efficient when goats are at high, medium and low densities. Skilled and motivated<br />

hunters are required. Large areas can be effectively covered with multiple camps of 2-3<br />

hunters spaced throughout.<br />

Mata Haris is a line-hunting technique adopted and improved from our local hunters and<br />

conservation practitioners in New Zealand. The technique involves a team of hunters<br />

working at fixed spacing (100-150m) and systematically moving through an area, typically<br />

proceeding into or perpendicular to the prevailing wind. Hunters maintain their place in<br />

the line by radio communications and hand-held GPSs with pre-determined points from<br />

the GIS. In this way, we produced a coordinated wall of hunters and dogs optimally spaced<br />

and covering swaths typically 3 km wide. This method is ideal for detecting animals at very low densities and covering areas<br />

systematically; it ensures that all areas are covered, and even the most wary animals are at risk. Deployment/retrieval of<br />

hunters and dogs by helicopter allows them to work remote areas and still remain ‘fresh’ for when goats are detected.<br />

Dogs<br />

Eradication methods<br />

“On large islands a range of methods used sequentially<br />

and simultaneously are required to put all animals at risk”<br />

New Zealand is the only country in the world where specialist goat dogs are<br />

employed by many hunters, providing breeds that facilitate training of pups due<br />

to natural instincts. A core breeding and training stock of five dogs was imported<br />

from New Zealand in 2000 and specialist dog trainers from there were employed<br />

to train hunters and develop trainers and a team of specialist goat dogs. Other<br />

hunting dogs from the Galapagos were selected for skills missing in the imported<br />

team and a team of over 70 skilled dogs was developed within 2.5 years.<br />

Certification at basic and advanced levels maintained dogs at high standards,<br />

and aversion training was conducted to ensure dogs were species specific and showed no interest in native wildlife. Hunters<br />

would work with one or two dogs each. Dogs were finder-bailers (dogs that track, find and contain the goats while waiting for<br />

the hunter to arrive), and could typically work with ground and air scents to detect and find goats. Dogs are highly effective with<br />

small groups of goats at low densities. They perform well in dense vegetation where other methods are ineffective, making them<br />

a key element when confronted with vast areas of that vegetation.<br />

Judas goats<br />

Goats are highly social and gregarious animals; they have an aversion to<br />

isolation, and will seek out others when isolated. The Judas goat method<br />

exploits these elements of goat biology to increase the cost efficiency of<br />

control and eradication operations when animals are at low densities. Judas<br />

goats are selected, captured, fitted with radio telemetry collars and released.<br />

They can then be tracked down and any associated feral goats will be<br />

removed. The Judas goat method is used as an accessory to other hunting<br />

methods, being most commonly used in conjunction with aerial hunting by<br />

helicopter and ground hunting with and without dogs.<br />

Judas goats increase the efficiency of removing animals at low density by reducing search time for hunters locating remnant<br />

herds or individuals. However, we discovered on Pinta that current Judas goat methodology fell short of its potential efficacy.<br />

The ideal Judas goat would search strongly for goats, be searched for by other goats, be sterile and not become wary. Reasons<br />

that goats may search for conspecifics include isolation and sexual cues. To maintain Judas goats in a state of isolation,<br />

managers in addition to shooting feral goats, shoot or capture any additional Judas goats associated with a particular Judas<br />

goat. Sexual cues involve both sexes searching strongly for mates, particularly when females are in estrus. Females in estrus<br />

actively search for males and likely attract them using pheromones. We developed protocols to sterilize, terminate pregnancy<br />

and induce female goats into a prolonged estrus with hormone implants. We then compared the efficiency of three types of<br />

Judas goats; sterile male, sterile female and sterile females in a prolonged estrus which we have dubbed Mata Haris (after the<br />

seductive and lethal World War I double agent).<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

15

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

16<br />

Chronological strategy<br />

Santiago<br />

The Project <strong>Isabela</strong> transitioned from pig monitoring to goat eradication on Santiago Island in December 2001. Delays in<br />

gaining access to funds and initiating contracting procedures for helicopters and other equipment forced us to look at<br />

other alternatives on where to have dogs and hunters working. Santiago filled that role; infrastructure in the form of trails and<br />

huts were already present and the hunters knew the island intimately. Santiago served as a training ground for dogs and<br />

ground hunters alike, allowing techniques to be refined and developed to suit our needs and the environmental conditions.<br />

Mustering into corrals by hunters on foot and on mules was used as an initial knockdown technique. This was followed by<br />

free hunting with dogs in all areas of the island. Ground hunters worked intensively; 85 trips were completed during the goat<br />

eradication with a peak of 21 trips in 2004. Trips averaged 2 weeks and typically involved 12-15 ground hunters with 2 dogs<br />

each. Up to 50 ground hunters and over 100 dogs were on the pay-roll at any one time in the first two years. In 2003, 18<br />

trips focused efforts on the densely vegetated area of Santiago. This strategy was adopted because helicopters, once they<br />

arrived, could quickly remove the bulk of the remaining population on the rest of the island and this area would remain the<br />

hardest part of the island from which to remove goats. Ground hunters removed 73,151 goats before helicopters came on the<br />

scene in February 2004; by the end of March another 12,912 goats had been removed, along with the last donkeys. The<br />

effectiveness of aerial hunting was apparent. Ground hunters and aerial crews had removed 99% of the goats; the remnant<br />

animals were wary of both methods, and a new technique was required to boost efficiency. In June, 122 Judas goats were<br />

systematically deployed on Santiago, followed by another 90 in December. Judas goats were initially checked by ground<br />

hunters with dogs, while in March 2005 aerial checks began. In August 2005 few goats were thought to remain; ground<br />

hunters with daily aerial support started systematically monitoring the island, working in rastrillo. The last feral goats were<br />

removed by ground hunters in November and at the end of the month all Judas goats were removed from Santiago. This<br />

assisted ground hunters and their dogs; any goat sign encountered would be from feral goats. Systematic swe<strong>eps</strong> continued<br />

until March 2006; no goat sign was detected. Santiago Island is now goat free for the first time in at least 80 years. At the end<br />

of March 2006, 20 Judas goats were deployed to monitor any deliberate goat re-introductions to the island.<br />

Timeline<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Duration: 5 years and 4 months<br />

• Goats removed: 89,474<br />

• Hunter hours: 65,031<br />

• Dog hours: 85,510<br />

• Helicopter hours: 921.6<br />

• JG deployed: 232<br />

• Days with Judas goat presence (up to March 31st 2006): 653<br />

• Hunter accidents: 1 broken leg due to a horse kick!<br />

6 knee & 1 ankle problem with surgical intervention<br />

Chronological strategy<br />

The sound of rotor blades turning over <strong>Isabela</strong> in April 2004 signaled the start of a massive campaign. Aerial hunting crews<br />

had refined techniques on Santiago that ensured that escapes were minimal (e.g. helicopter crews were often deployed to<br />

shoot goats spotted seeking refuge in caves). Aerial hunting began on Wolf and Ecuador volcanoes, then rolled south to<br />

Darwin and Alcedo. The initial knockdown took seven months, resulting in 55,575 goats being removed, and donkeys being<br />

eradicated on Alcedo volcano. This phase was interrupted by a helicopter accident in June 2004; fortunately no one was<br />

injured but the aircraft was a write-off. <strong>Isabela</strong> was largely an aerial operation with limited but strategic use of ground hunters<br />

and dogs; only 7 trips were conducted, the majority of which were in densely vegetated areas. Vegetation consisting of a<br />

canopy of trees and lower vegetation forming an additional under canopy reduced visibility of goats from the air. Aerial<br />

hunting removed the bulk of the animals but ground hunters demonstrated the efficiency of that method in near ideal<br />

conditions with goats that were naive to ground hunters and dogs. By December 2004 goats were at low densities. Over the<br />

next three months some 700 Judas goats were deployed on the northern and southern part of <strong>Isabela</strong>. A further 70 Judas goats<br />

were deployed in late 2005 on the remainder of southern <strong>Isabela</strong>. On this island, Judas goat monitoring was conducted<br />

exclusively by helicopter. Twelve months of intensive Judas goat monitoring was conducted; 915.7 accident free flying hours<br />

resulted in 7,363 checks, 1,236 recaptures and redeployments and 4,524 feral goats removed. Northern <strong>Isabela</strong> is now free of<br />

feral goats; the last goat was removed from Alcedo in December 2005. Southern <strong>Isabela</strong> has been controlled to extremely low<br />

numbers; possibly 20-30 animals remain. Operations finished at the end of March 2006. 266 Judas goats were left as their<br />

removal would be expensive. As they are sterile there is no risk of repopulating the island and they may be useful for future<br />

monitoring efforts.<br />

Timeline<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Duration: 2 years<br />

• Goats removed: 62,818<br />

• Hunter hours: 5,161<br />

• Dog hours: 8,877<br />

• Helicopter hours: 2,320<br />

• JG deployed: ~700<br />

• Days with Judas goat presence (up to March 31st 2006): 465<br />

• Accidents: 1 heavy landing and 1 emergency landing w/o tail rotor blade control.<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong><br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

17

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

18<br />

Ground hunting management<br />

Santiago: ground hunter land<br />

Massive areas made manageable<br />

At 58,465 ha Santiago Island is more than 3 times the size of<br />

Washington DC; it is too large for ground hunters or even a<br />

helicopter to work as a single block. The island has no roads or<br />

fences and is over 35 km long and 21 km wide. The division of the<br />

island into 24 blocks for ground hunters allowed the entire island to<br />

be worked systematically. Satellite imagery was used to assess the<br />

island geography; wavelength band combinations were used to<br />

highlight vegetation types and volcanic areas. GPS units were used to mark existing trails throughout the island. Natural<br />

topographic features, easily identified by hunters (e.g., ridgelines, hills, etc), were also identified. Ground hunting blocks<br />

were subdivided into a total of 137 sub-blocks which facilitated the specialized rastrillo ground hunting technique and<br />

provided optimally sized areas for teams of 15 hunters to cover in one day. Sub-blocks in open areas were on average twice<br />

the size of the Principality of Monaco (384 ha) and those in heavily vegetated areas were about 171 ha.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Ground hunters: 100% Galapageños<br />

• 20% from <strong>Isabela</strong>, 80% from Santa Cruz<br />

• Highly qualified hunters<br />

- Hunting skills<br />

- GPS handling<br />

- Rifle maintenance<br />

- First aid intervention training<br />

• 147 dogs bred in PI kennel<br />

• 2 qualification levels for dogs<br />

Dogs wearing special leather boots for protecting their<br />

paws when working on lava during hot days.<br />

Not Welcome<br />

While Santiago Island has a good network of trails, several camps<br />

and water collecting sites, <strong>Isabela</strong> Island is far from providing the<br />

same level of hospitality. Moreover, a large proportion of the island<br />

is covered by lava fields and thus large areas of the island are not<br />

practically workable from the ground. Size, remoteness and<br />

complex access are additional factors that make <strong>Isabela</strong> a difficult<br />

island to work on.<br />

Darwin volcano is a good example. Probably the driest of all,<br />

it has around 64% of its area covered by volcanic rocks. Wolf with<br />

its steep slopes and high altitude also offers a big challenge.<br />

Alcedo presents probably the best conditions as well as having a<br />

hut and water collector on the rim. The Linda Cayot hut is<br />

accessible by a moderate climbing trail. The southern part of<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>, even though it has existing trails and a National Park hut,<br />

offers a challenge, not only because of its size, but also because of<br />

the huge lava fields.<br />

For all these reasons, helicopters were chosen and have proven to<br />

be the best hunting and monitoring tool for tackling <strong>Isabela</strong> Island.<br />

Aerial hunting management<br />

FACT BOX<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>: helicopter land<br />

• Helicopter model: MD500D/MD500E<br />

• Capacity: 1 pilot and up to 3 passengers<br />

• Airspeed: Hover to 156 knots<br />

• Range: 225 Nautical miles ~2.2 hours @110 knots<br />

• Lifting capacity: 500kg<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

19

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

20<br />

Judas goats management<br />

Releasing Judas goats<br />

Deploying Judas goats<br />

Judas goats for Santiago were captured on <strong>Isabela</strong> and<br />

underwent quarantine procedures before being transported<br />

by boat to sites (Puerto Nuevo and La Bomba) for loading<br />

into the helicopter. Quarantine is a common procedure<br />

when traveling between islands to prevent foreign species<br />

from being transported from one island to another, in this<br />

case in particular seeds in the stomach, hair or hooves.<br />

Deployments were conducted systematically by flying a<br />

load of 10-12 Judas goats and deploying them at<br />

predefined locations that were 2.25 km apart in vegetated<br />

areas and 3 km apart in lava areas. Flight paths for<br />

deploying each load of Judas goats were planned to<br />

minimize flight time. The map of Santiago shows each<br />

load of Judas goats in a different color, with the<br />

helicopter’s GPS tracks. Each load of Judas goats took<br />

around 30 minutes of flight time to deploy. On <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

Island, 700 Judas have been deployed on the northern and<br />

southern parts at similar spacings, using the same<br />

deployment strategy as Santiago.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• >700 Judas deployed<br />

• 33% males<br />

• 33% females<br />

• 33% Mata Haris<br />

Making Judas goats more efficient<br />

From feral to Judas: 9 st<strong>eps</strong><br />

Project staff implemented new techniques to maximize the efficacy of their Judas goats.<br />

Goats were sterilized, pregnancies were terminated by a hormone injection and Mata<br />

Haris were females implanted with hormones to induce a prolonged estrus effect.<br />

Sterilization techniques were selected to maintain normal hormone levels in males and<br />

females to ensure no alteration in their behavior. Males were sterilized with a technique<br />

similar to a vasectomy, while the fallopian tubes were tied in the females.<br />

1. Capture 2. Injection to terminate pregnancy<br />

3. Ferry to camp<br />

4. Ear tagged & quarantine<br />

(if going inter-island)<br />

5. Sterilization procedures<br />

6. Hormone implant for Mata Haris<br />

7. Collared 8. Loaded<br />

9. Deployed<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• 600 telemetry collars<br />

• Frequency range: 170-174MHz, with transmitters<br />

at 10KHz spacings<br />

• Weight: ~400 g.<br />

• Battery: Lithium with ~5 year life<br />

• Activation: with magnet swipe over a reed switch<br />

• Signal – line of sight: typically up to 6 km on ground,<br />

and up to 50 km from helicopter<br />

• Color: Day-glow orange<br />

Maps: a daily tool for monitoring<br />

Helicopter crews monitored Judas goats intensively. Maps with the last<br />

position of each Judas goat were provided to crews and updated daily. Maps<br />

indicated the unique ear tag number and collar frequency of each Judas goat<br />

and allowed crews to effectively manage over 600 goats. Judas goats need to be<br />

kept alone to maintain their searching behavior. When Judas goats were found<br />

together (see Association potential situation), all goats apart from one were<br />

captured and re-deployed (see Action Taken potential situation). Maps<br />

identified areas that Judas goats had moved out of, providing an indication of<br />

where to re-deploy captured Judas goats.<br />

Event (or collected) information:<br />

• Date<br />

• Ear tag<br />

• Geographical position (GPS)<br />

• Association (see box)<br />

• Action taken (see box)<br />

• # Goats removed<br />

Judas goats management<br />

Monitoring Judas goats<br />

ASSOCIATION<br />

with ferals & Judas, with Judas, with ferals, alone<br />

ACTION TAKEN<br />

Kill, Freed, Capture/translocated, Found dead, Escape/Not found<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

& STRATEGY<br />

21

RESULTS & EFFORT<br />

What has been done<br />

RESULTS & EFFORT<br />

Before & after: Santiago 24<br />

Santiago 25<br />

- Ground hunting phase<br />

- Aerial hunting phase<br />

- Judas phase<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong> 29<br />

- Aerial hunting phase<br />

- Ground hunting phase<br />

- Judas phase<br />

Judas goats´ movements 33<br />

- An example<br />

Before & after: <strong>Isabela</strong> 34<br />

23

24<br />

Before & after: Santiago<br />

Vegetation recovery in the highlands<br />

March 1999<br />

March 2005<br />

Tremendous ground hunting effort was invested on Santiago Island between<br />

December 2001 and June 2004. The northern side of the island shows the high<br />

numbers of goats that have been eradicated. Added to this are the results obtained doing<br />

mustering and corrals which were not included in the final block results.<br />

Despite the fact that the spatial dimension has always been taken into account for work<br />

planning, early data were not gathered using a methodology that could be integrated in<br />

the GIS and thus are not on the map; a lesson learnt throughout the project.<br />

Not on map:<br />

• 22,732 goats<br />

• 21,221 mustering hours<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Approximate distance walked<br />

by hunters<br />

• Total hunting: 26,725 km<br />

- 2001: 880 km<br />

- 2002: 7,656 km<br />

- 2003: 12,100 km<br />

- 2004: 6,089 km<br />

Time worked<br />

• Total hunting: 44,207 hrs<br />

- 2001: 7,060 hrs<br />

- 2002: 12,844 hrs<br />

- 2003: 16,927 hrs<br />

- 2004: 7,376 hrs<br />

Santiago: ground hunting phase<br />

Yearly results per method<br />

Learning while eradicating<br />

Mustering & corrals:<br />

1 : 2,600 goats, 238 hrs<br />

2 : 1,224 goats, 224 hrs<br />

3 : 3,000 goats, 420 hrs<br />

4 : 290 goats, 168 hrs<br />

5 : 40 goats, ~300 hrs<br />

6 : 2,500 goats, 420 hrs<br />

7 : 235 goats, 60 hrs<br />

8 : 1,500 goats, 1071 hrs<br />

Hunters walked the equivalent of 67% of the earth’s<br />

circumference during the hunting phase.<br />

25<br />

RESULTS & EFFORT

RESULTS & EFFORT<br />

26<br />

Santiago: aerial hunting phase<br />

Hunting effort<br />

Interpreting helicopter movements on Santiago<br />

The GPS track from helicopter operations on Santiago during the hunting phase shows where effort was focused. Goats were<br />

easily detected and frequented the edges of lava flows; these areas were regularly flown and many goats were eliminated. Other<br />

landscape features that goats frequent, such as hills and lines of caves, can also be seen as concentrations of hunting activity.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Hunting km flown<br />

• 19,687 km total (Quito to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia)<br />

- 18,708 km in 2004<br />

- 979 km in 2005<br />

Hunting hrs flown<br />

• 271.8 hrs total (11.3 days non-stop)<br />

- 262.6 hrs in 2004<br />

- 9.2 hrs in 2005<br />

Tracking down the machine!<br />

The helicopter’s GPS was programmed to log<br />

a point every 20 seconds, from which the<br />

flight track is constructed. After downloading<br />

GPS data these points are joined together in<br />

their time sequence to provide a track,<br />

represented as a line on a map.<br />

Helicopters at work!<br />

Pin-pointing the goats<br />

Santiago: aerial hunting phase<br />

Hunting results<br />

On Santiago, two helicopters were used intensively. Within two months nearly 13,000 goats were removed. A combination of<br />

ground hunters with dogs working the densely vegetated southern slope and the simultaneous use of helicopters working the<br />

remainder of the island was highly effective. With combinations of methods such as these, the population was quickly driven<br />

to zero. As goat numbers decreased, Judas goats were introduced to increase the efficiency of ground and aerial hunters<br />

because of reduced search time.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Period: February to March 2004<br />

• 12,912 goats eradicated<br />

• 15% of total goats eradicated<br />

• 94% eradicated 0-500 m. alt.<br />

• 6% eradicated >500 m. alt.<br />

Highest densities of goats were<br />

encountered in dry open and scrub areas.<br />

Each helicopter and ground hunter had a GPS to allow managers to see that all areas of the<br />

island had been covered and where goats had been killed or escaped. This spatial information<br />

was used in determining when changes in methods were required. The dots on the map show<br />

GPS waypoints where groups of goats were shot by aerial hunting crews. Manual counters were<br />

used by shooters to record the number of goats shot, allowing us to later calculate the number of<br />

goats killed per waypoint.<br />

27<br />

RESULTS & EFFORT

RESULTS & EFFORT<br />

28<br />

Santiago: Judas phase<br />

Judas goats strategy outcomes<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Helicopter facts<br />

• 13,390 km flown of which:<br />

- 2%(2004), 97%(2005), 1%(2006)<br />

• 9.6 days non-stop equivalent<br />

Ground facts<br />

• August 2004 to July 2005<br />

• 14 trips<br />

General facts<br />

• 913 Judas released on checks<br />

• 284 Captured & translocated<br />

Judas goats on Santiago<br />

Judas goats were monitored by ground and aerial<br />

hunting crews on Santiago about 1,400 times.<br />

Ground hunters invested 5,010 hours and dogs<br />

7,720 hours, while 231 helicopter hours were<br />

flown. Kills in this phase accounted for 1% of all<br />

goats killed on Santiago. Some 617 goats were<br />

killed associated with Judas goats; 319 and 298<br />

were killed by aerial and ground checks respectively.<br />

A further 557 goats were killed unassociated with<br />

Judas goats; 97 and 460 were killed by aerial and<br />

ground checks respectively. On average, ground<br />

hunter checks were nine times more expensive than<br />

helicopter checks. However, as dogs detected more<br />

goats that were not associated with Judas goats, the<br />

final costs per goat killed during this phase were<br />

almost identical for helicopter and ground crews.<br />

Group sizes of goats killed during the Judas goat<br />

phase on Santiago. Purple dots indicate feral goats<br />

killed that were not associated with Judas goats. Pink<br />

dots are feral goats that were shot while associated<br />

with Judas goats.<br />

Ideal helicopter country<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>: aerial hunting phase<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Hunting results<br />

On <strong>Isabela</strong>, helicopter crews removed 98% of all goats; the terrain and vegetation was, in general, ideal for aerial hunting.<br />

Goats were shot on all volcanoes, with the highest densities occurring on Alcedo, Darwin and Wolf. Aerial hunting was<br />

extremely efficient and allowed areas to be covered that would have been near impossible to cover by foot. One area<br />

proved difficult to hunt from the air. Dense vegetation on the southern slopes of Alcedo was hunted intensively but many<br />

animals still remained. Goats altered their behavior, becoming motionless and hiding under vegetation where they were<br />

generally safe from detection by aerial crews. Methods were switched after aerial hunting had removed all the animals<br />

possible (read further p.30).<br />

Period: May, June & December 2004 + January<br />

to March 2005<br />

• 56,657 goats eradicated<br />

• 98% of total goats eradicated<br />

• 46,664 in 2004 & 9,993 in 2005<br />

• 54% eradicated 0-500 m. alt.<br />

• 33% eradicated 500-1000 m. alt.<br />

• 13% eradicated > 1000 m. alt. & inside craters<br />

* Unlike on Santiago Island, no black goats were seen<br />

on <strong>Isabela</strong> Island<br />

Hunting km flown<br />

• 72.761 km total (1.8 times the earth’s circumference)<br />

• 43,957 km in 2004<br />

• 27,533 km in 2005<br />

• 1,271 km in 2006<br />

Hunting hrs flown<br />

• 1,258 hrs total (52.4 days non-stop)<br />

• 930 hrs in 2004<br />

• 312 hrs in 2005<br />

• 16 hrs in 2006<br />

Tracking on down <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

With Santiago’s recent experience fresh in their<br />

minds, the helicopter crews were well prepared<br />

when they arrived on <strong>Isabela</strong>. After a general<br />

orientation flight aimed at identifying some of the<br />

goat’s living areas, the hunting phase was<br />

launched. A whole month based on volcano Wolf<br />

enabled them to work the northern part of <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

thoroughly, flying more and spending more time<br />

than originally planned due to the unexpected<br />

high number of goats.<br />

After being based at a temporary camp<br />

on northern <strong>Isabela</strong>, the group then<br />

moved to the permanent camp where<br />

they were based until the end of March<br />

2006; Cowley base in Alfaro Point, on<br />

the eastern side of <strong>Isabela</strong>. From there,<br />

work was targeted on Alcedo and<br />

Darwin. Alcedo stands out as the<br />

problematic volcano as it had the<br />

largest goat population. Hunting flying<br />

time and kilometers flown are on a<br />

different magnitude than any previous<br />

job! The flying tracks on the map show<br />

how all of Alcedo area is suitable for<br />

goats, as opposed to any other volcano<br />

where more lava areas restrict the<br />

populations into the smaller reduced<br />

vegetated regions.<br />

29<br />

RESULTS & EFFORT

RESULTS & EFFORT<br />

30<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>: ground hunting phase<br />

Ground hunters to the rescue<br />

A strategy for dense vegetation<br />

Aerial hunting removed 6,077 animals from Alcedo’s densely vegetated southern slope (see zone of interest in the map). The<br />

remaining goats had become wary of this method and kill rates dropped to 1.5-2 goats per flight hour. In anticipation, ten<br />

water catchments were set up at 3 km intervals throughout this zone. Groups of 2-3 hunters and their dogs were based at<br />

water catchments for 12 days for three consecutive trips.<br />

Hunters´ tracks Goats killed<br />

First trip in January 2005: 3.6 goats per hunter day<br />

Second trip in February 2005: 0.7 goats per hunter day<br />

The images below show hunters’ GPS tracks and positions of goats killed. The second and third trips killed approximately<br />

one-tenth the number killed the previous trip. Aerial hunting was simultaneously conducted around this zone, removing<br />

goats attempting to flee the area. At the end of the third trip Judas goats were deployed in this area.<br />

“Water catchments”<br />

Hunters´ tracks Goats killed<br />

Third trip in June 2005: 0.07 goats per hunter day<br />

31<br />

RESULTS & EFFORT

RESULTS & EFFORT<br />

32<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>: Judas phase<br />

Judas goats strategy outcomes<br />

Judas goats on <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

After having refined their techniques on Santiago for Judas goat capture, sterilization, deployment and tracking, <strong>Isabela</strong>,<br />

although much larger was in many ways simpler, as teams knew their roles and were highly efficient. Prior to Santiago the<br />

world’s largest Judas goat operation involved around 30 Judas goats, and this was the Judas goat facilitated eradication on<br />

Pinta. The scale at which the campaign was now being conducted was by all standards massive. A database specifically<br />

designed for keeping track of Judas goats kept our GIS specialist and one data entry person occupied; daily entries of more<br />

than 60 Judas goat checks, associated kill and GPS data were not uncommon (see p.21 for information collected in Event<br />

information box). Aerial crews were also busy, often daily capturing and re-deploying more than 10 Judas goats, with a<br />

maximum of 38 in one day. In total 591 Judas goats were checked 5470 times; 3439 goats were shot associated with these<br />

Judas goats, while 1085 were shot but not associated with a Judas. A high proportion of the last goats removed were females<br />

with juvenile kids. Some females will go solitary to give birth and then remain alone with their kids until they become<br />

sexually active again. These females and their kids will typically not be detected by Judas goats until these kids are sexually<br />

mature. Judas goat campaigns must incorporate this factor into their planning. Mata Haris associated with more feral males<br />

than female or male Judas goats (see graph). However, overall there was no statistical difference in the overall number of<br />

goats that each of the three types associated with. In future<br />

campaigns the intensive use of Mata Haris may assist in removing<br />

males at a fast enough rate so that breeding does not occur with the<br />

last females, as was seen on Santiago.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Helicopter facts<br />

• 78,311 km flown of which:<br />

- 20%(2005) and 80%(2006)<br />

• 38 days non-stop equivalent<br />

Group sizes of goats killed during the Judas goat phase on <strong>Isabela</strong>. Blue dots indicate feral<br />

goats killed that were not associated with Judas goats. Red dots are feral goats that were<br />

shot when associated with Judas goats.<br />

Mata Hari JGs performed ~1.5 times better than female or male JGs<br />

at detecting feral males, while there was no difference in the<br />

probability of any JG type detecting females.<br />

Walking the distance!<br />

Judas goats´ movements<br />

An example<br />

Monitoring Judas goats gave crews and managers detailed insight into the movements, preferred location and abilities of<br />

goats. The original plan to eradicate goats from northern <strong>Isabela</strong> assumed that the Perry Isthmus could be used as a barrier<br />

to immigration from the south. Monitoring Judas goats on <strong>Isabela</strong> soon dispelled that idea; some goats repeatedly traveled<br />

45 km from the north of Wolf volcano to Alcedo, typically in 10-12 days. The majority of Judas goats averaged 3.6 km<br />

movements between checks; only 8% of movements were greater than 10 km. Notice that these linear distances between<br />

checks don’t take into account the sinuosity of JG movements. Judas goats provided a worst case scenario that couldn’t be<br />

ignored. To compensate for the wrong assumption that goats could be held at the Perry Isthmus, it was decided to expend as<br />

much extra effort as possible in driving the southern goat population towards zero. Ever-dwindling helicopter hours were<br />

finely balanced between checking Judas goats on northern <strong>Isabela</strong> and Santiago, moving ground hunters and extending<br />

hunting and Judas goat zones into the remainder of southern <strong>Isabela</strong>. The buffer zone (Perry Isthmus south of Alcedo<br />

volcano) that had been assumed could prevent immigration from the south, turned into an intensive aerial hunting zone,<br />

followed by the deploying and monitoring of Judas goats in the few months left. The population was driven to extremely low<br />

levels but eradication in this short time was unlikely. However, the measure was primarily carried out as a way of<br />

maintaining the results achieved in the north.<br />

Perry Isthmus<br />

33<br />

RESULTS & EFFORT

34<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong> before...<br />

Already reversing the situation!<br />

Volcano<br />

1977<br />

1997<br />

... and <strong>Isabela</strong> after<br />

Already reversing the situation!<br />

Alcedo<br />

2006<br />

2006<br />

35

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

Investing time and $<br />

Efficiency of operations 38<br />

- Aerial hunting<br />

- Aerial monitoring<br />

- Comparison of phases<br />

Costs of operations 43<br />

- Aerial hunting<br />

- Aerial monitoring<br />

- Ground monitoring<br />

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

37

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

38<br />

Efficiency of operations<br />

Aerial hunting phase<br />

The maps on these pages (38-39-40-41) show spatially where effort has been invested, where goats were removed<br />

and how much effort it took to remove each goat (refer to titles). The blocks shown here were used by managers to<br />

delineate hunting units for aerial hunting crews. Color coding shows these values; white represents the average value,<br />

cold colors (blues, purple and light green) represent below-average values while warm colors (reds and oranges) show<br />

above-average values. Grey areas indicate where there are no values. Standard deviation (STD) values from each data<br />

set are the increments used to guide each color or value change. Pages 38 and 39 show the aerial hunting phase. The<br />

following pages (40 and 41) present the aerial monitoring phase. All data sets values are normalized to the size of the<br />

hunting blocks (ex.: Effort = time flown/ha or Animals removed = animals/ha).<br />

EFFORT<br />

ANIMALS REMOVED<br />

Cowley Camp<br />

Cowley Camp<br />

La Bomba<br />

La Bomba<br />

Effort<br />

This map shows where flight hours were invested.<br />

The presence of helicopter base camps at La Bomba and<br />

Cowley show high flying hours due to ferry time over those<br />

blocks to get to any other block.<br />

Animals removed<br />

Alcedo had high densities of goats removed, while vegetated<br />

areas on Darwin and Wolf volcanoes had medium densities.<br />

On Santiago, arid areas had medium densities, while the lava<br />

field and dense vegetation had lower numbers removed by<br />

aerial hunting. Areas of dense vegetation on Santiago were<br />

primarily searched by ground hunters with dogs, and the<br />

animals removed from there are obvioulsy not shown on these<br />

maps for aerial hunting.<br />

Goats per unit effort<br />

As a measure of efficiency we refer to animals removed per unit effort. This is calculated by dividing the number of animals<br />

removed by the number of hours invested.<br />

This map shows the relative number of animals removed per unit of effort (e.g. per hour of aerial hunting). Note that areas<br />

where camps were based have lower values (blue), this is an artifact of helicopter ferry time over these areas to reach other<br />

blocks. Some areas had few goats; effort invested searching for them produces dark blue areas, as seen on the majority of<br />

Cerro Azul in south-western <strong>Isabela</strong>. Areas where high densities of goats were removed with little effort that weren’t in flight<br />

paths (between camps or to other hunting areas) are shown in red. These areas often coincide with vegetation that was<br />

open, allowing for aerial hunting to be highly efficient in detecting and removing animals.<br />

GOATS PER UNIT EFFORT<br />

Cowley Camp<br />

La Bomba<br />

39<br />

EFFICIENCY & COSTS

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

40<br />

Efficiency of operations<br />

Aerial monitoring phase<br />

EFFORT<br />

ANIMALS REMOVED<br />

Cowley Camp<br />

Cowley Camp<br />

La Bomba<br />

La Bomba<br />

Effort<br />

Helicopter flying time expended was influenced by two<br />

primary factors; the number of Judas goats present in that area<br />

and the frequency at which they were checked. These factors<br />

were influenced to some degree by the density of remnant<br />

animals; managers concentrated more effort in areas with<br />

higher densities of goats.<br />

The Cowley base camp block has an inflated effort due to<br />

ferry time. On Santiago, Puerto Nuevo acted as a refueling<br />

site during this phase, influencing the amount of effort<br />

expended there.<br />

Animals removed<br />

Management actions, such as not hunting intensively on the<br />

western slopes of Alcedo during the aerial hunting phase to<br />

facilitate later capture of Judas goats, influence the number of<br />

animals removed during monitoring phase. On southern<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong>, little aerial hunting was conducted prior to the<br />

monitoring phase. Other areas with refuges, such as networks<br />

of caves and lava tubes, allowed goats to remain at higher<br />

densities during the aerial hunting phase; these animals were<br />

then detected and removed during the monitoring phase.<br />

Goats per unit effort<br />

Goat per unit effort shows where remnant goats survived the initial knockdown phase, or reflect the management regimes.<br />

For example, on the western slopes of Alcedo goats were not hunted intensively during the initial aerial hunting phase so that<br />

this area could provide a later source of Judas goats. All of southern <strong>Isabela</strong> was hunted during the monitoring phase; kills<br />

shown reflect the entire population rather than remnant populations. Due to management decisions, relatively large numbers<br />

of animals were removed from the rest of Alcedo and a lowland section of Sierra Negra in southern <strong>Isabela</strong> in this phase (see<br />

Results & effort section, p32).<br />

GOATS PER UNIT EFFORT<br />

Cowley Camp<br />

La Bomba<br />

41<br />

EFFICIENCY & COSTS

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

42<br />

Efficiency per phase<br />

Aerial efficiency ratios<br />

When should methods change? When<br />

one method becomes inefficient or is<br />

resulting in unnecessary escapes then<br />

methods need to be modified or<br />

changed. The map to the left compares<br />

aerial efficiency (kills/flight hour) during<br />

various phases of the campaign: aerial<br />

hunting phase (broken down in three<br />

stages: first 2 hours, last 2 hours and<br />

overall) and Judas phase. Efficiency<br />

clearly goes down from the first 2 hours,<br />

to the last 2 and finally to the Judas<br />

phase. The yellow line indicates 20<br />

goats/hour, a point used to provide a<br />

rough indication that Judas goats may<br />

soon need to be released. Note that the<br />

2 last aerial hunting hours refer to the<br />

hours before changing to Judas phase<br />

and thus are always around the 20<br />

kills/hour mark. Ground hunting was<br />

conducted again when goats were below<br />

this level.<br />

In blue: efficiency ratio between the<br />

beginning and the end of the aerial hunting<br />

phase. A longer bar expresses how much<br />

more efficient (in terms of animals killed per<br />

hour) were the first hours of the hunting<br />

phase versus the last hours during the same<br />

phase.<br />

In red: efficiency ratio between aerial<br />

hunting phase and Judas phase.<br />

A longer bar expresses how much more<br />

efficient (in terms of animals killed per hour)<br />

was the hunting phase versus the Judas<br />

phase.<br />

The graphs confirm a ratio that had<br />

been anticipated.<br />

Yellow line: a visual mark that represents a<br />

4-fold magnitude in the ratio scale, shown<br />

to help comprehension of the graphs.<br />

Costs of operations<br />

Overall budget<br />

The Santiago and <strong>Isabela</strong> campaigns were conducted together. Santiago was a training ground where methods were<br />

refined, dogs were trained and experimental approaches taken. Overall efficiency there was lower, giving elevated costs<br />

for that campaign and lower costs for the <strong>Isabela</strong> campaign. Once teams reached <strong>Isabela</strong> they were highly experienced,<br />

efficient and were dealing with naive animals. By combining both campaigns we benefited from economies of scale.<br />

Santiago Judas, 8%<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong> Ground, 6%<br />

Project <strong>Isabela</strong>´s overall allocation of expenditures<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong> Judas, 17%<br />

Santiago Corrals, 3%<br />

Santiago Aerial, 4%<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong> Aerial, 15%<br />

Santiago Ground, 47%<br />

43<br />

EFFICIENCY & COSTS

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

44<br />

Costs of operations<br />

Aerial hunting phase<br />

The following maps use 150 ha polygons, within which effort (i.e. the number of animals removed and the number of<br />

animals removed per unit effort) is shown. Effort is expressed in $ which is calculated from known costs per helicopter<br />

flying hour. These blocks were not used by management to delineate hunting areas, but are shown in this form to remove<br />

biases in block size and management boundaries. Aerial hunting was conducted intensively throughout areas with highmedium<br />

goat densities. Santiago had high densities of goats with a large number of caves and dense vegetation patches in<br />

which they would take refuge; costs were on average 2.3 times higher per hectare for Santiago. Some areas that were<br />

suspected to have no goats, such as south-western <strong>Isabela</strong>, had no aerial hunting activities conducted; monitoring with Judas<br />

goats was the first method employed in these areas.<br />

Spatial repartition of aerial hunting $ spent<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Cost per helicopter flight hour: $1,252<br />

• Santiago<br />

- Aerial hunting cost: $360,954<br />

(7% of Santiago operation)<br />

- Aerial hunting cost per ha: $6.17<br />

• <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

- Aerial hunting cost: $1,212,572<br />

(35% of <strong>Isabela</strong> operation)<br />

- Aerial hunting cost per ha: $2.64<br />

Some areas were flown that resulted in no kills (magenta areas) but these were<br />

essential to provide effective coverage of the island during this phase.<br />

Cheap or expensive goats?<br />

Costs of operations<br />

Aerial hunting phase<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Santiago<br />

- Aerial hunting cost per goat: $30*<br />

• <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

- Aerial hunting cost per goat: $20*<br />

* aerial operation cost / # goats<br />

Results have been compiled on the basis of and homogenous<br />

matrix of 150 ha hexagons to show a more realistic situation.<br />

Compilation of the helicopter managing blocks would not have<br />

provided the same visual effect (see managing blocks page 19).<br />

45<br />

EFFICIENCY & COSTS

EFFICIENCY & COSTS<br />

Costs of operations<br />

Aerial monitoring of Judas<br />

These maps show where helicopter effort was expended and translate this effort into dollars. On the left the cost of<br />

checking Judas goats is shown spatially; grey areas had Judas goats deployed in or near-by, and although no monitoring<br />

events were conducted there, this ensured complete coverage of the island. The map on the right provides cost per kill for<br />

feral goats removed that were associated with Judas goats, providing a function of cost expended and the number of feral<br />

goats removed. Although many polygons indicate that no goats associated with Judas goats, these checks are required to<br />

ensure systematic and complete coverage of the islands.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Santiago<br />

- Cost per Judas check: $207.52<br />

- Average cost per feral: $569<br />

• <strong>Isabela</strong><br />

- Cost per Judas check: $191.37<br />

- Average cost per feral: $308<br />

Costs of operations<br />

Ground monitoring of Judas<br />

Ground hunters were also used to check Judas goats on Santiago. Costs per Judas goat check were nine times higher for<br />

ground hunters than for checks by helicopter. However, ground hunters removed significantly more goats unassociated<br />

with Judas goats between checks; when this is taken into consideration then cost per goat removed between the two methods<br />

is comparable. Additionally, ground hunters would take more than a month to check all Judas goats on Santiago, while a<br />

helicopter would check all Judas goats in 2-3 days. The speed at which Judas goats can be checked influences how many<br />

goats can be removed and thus affects the potential reproductive capacity of the remnant population. By removing goats<br />

faster, the end result is that there are fewer animals to be removed. Cost/goat removed does not take these factors into account.<br />

46 47<br />

FACT BOX<br />

• Santiago<br />

- Cost per Judas check: $1798.77<br />

- Cost per feral: $595<br />

EFFICIENCY & COSTS

CONFIRMING ERADICATION &<br />

ECOLOGICAL EXTINCTION<br />

Achieving our goals!<br />

CONFIRMING ERADICATION<br />

& ECOLOGICAL EXTINCTION<br />

Santiago 50<br />

<strong>Isabela</strong> 52<br />

49

CONFIRMING ERADICATION<br />

& ECOLOGICAL EXTINCTION<br />

50<br />

Santiago: searching for the last goats<br />

Systematic monitoring<br />

Monitoring Santiago<br />

In August 2005 few goats were thought to remain on the island and ground hunters initiated systematic rastrillo swe<strong>eps</strong> of all<br />

vegetated areas of the island. Twelve trips were conducted with up to 26 hunters and 64 dogs per trip. Nearly 12,000 hunter<br />

hours were invested covering around 10,000 km. Three complete swe<strong>eps</strong> of the island were conducted; areas where goats<br />

were shot on the first and second swe<strong>eps</strong> were covered several times. To maintain hunter morale, increase efficiency and to<br />

increase the speed at which the island could be covered, ground hunters and dogs were moved daily by helicopter.<br />

Aerial support of ground hunters<br />

Helicopter logistical support of ground hunters,<br />

for moving hunter and dog food, water and<br />

equipment, dramatically increased hunter morale<br />

and efficiency.<br />

In the last nine months of the Santiago campaign,<br />

ground hunters were ferried daily to or from<br />

work sites. The helicopter’s GPS tracks show<br />

where hunters were camped and where they<br />

were deployed or picked up. Moving hunters by<br />

helicopter allowed them to nearly double the<br />

number of kilometers invested in hunting instead<br />

of spending time traveling on trails to and from<br />

work sites. Hunters typically logged 80 km of<br />

GPS track in a 10 day period. Distance covered<br />

was limited by weather. In summer dogs could<br />

not work past 10AM as scent would burn off the<br />

ground and also dogs would overheat. As<br />

helicopter support was limited to daylight hours,<br />

hunters were limited in the number of effective<br />

hours they could work per day.<br />

FACT BOX<br />

Ground work:<br />

• 9 months of systematic<br />

island monitoring<br />

• 12 trips<br />

• 10,121 km walked<br />

Aerial work:<br />

• 7 months of logistic support (LS)<br />

• Nearly 220 hours flown in LS<br />

• Nearly 19,000 km flown in LS<br />

Feral FREE!<br />

Santiago: last goats & last Judas<br />

Confirming eradication<br />

The last four goats were shot on Santiago by ground hunters working in rastrillo hunting system. They were found in dense<br />

vegetation on the southern slope of the island on November 25th 2005. All were adult females, and none was pregnant. The<br />

last adult feral male had been removed four months earlier. Throughout the last year of the campaign we estimated the age of<br />

kids and measured fetuses in any pregnant females shot, to determine when they had conceived. As male Judas goats were<br />