Find out more by downloading our programme notes - BBC

Find out more by downloading our programme notes - BBC

Find out more by downloading our programme notes - BBC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

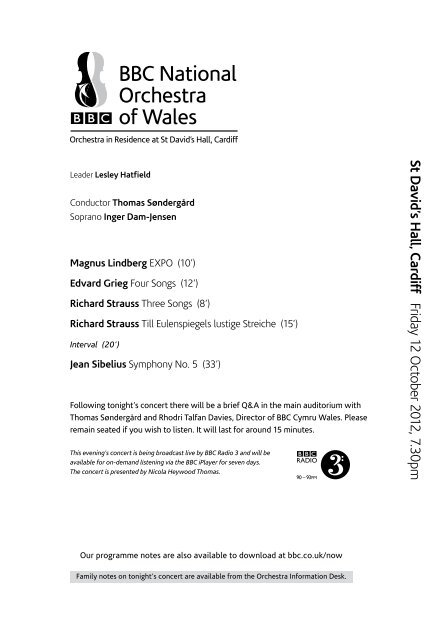

Leader Lesley Hatfield<br />

Conductor Thomas Søndergård<br />

Soprano Inger Dam-Jensen<br />

Magnus Lindberg EXPO (10’)<br />

Edvard Grieg F<strong>our</strong> Songs (12’)<br />

Richard Strauss Three Songs (8’)<br />

Richard Strauss Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche (15’)<br />

Interval (20’)<br />

Jean Sibelius Symphony No. 5 (33’)<br />

Following tonight’s concert there will be a brief Q&A in the main auditorium with<br />

Thomas Søndergård and Rhodri Talfan Davies, Director of <strong>BBC</strong> Cymru Wales. Please<br />

remain seated if you wish to listen. It will last for around 15 minutes.<br />

This evening’s concert is being broadcast live <strong>by</strong> <strong>BBC</strong> Radio 3 and will be<br />

available for on-demand listening via the <strong>BBC</strong> iPlayer for seven days.<br />

The concert is presented <strong>by</strong> Nicola Heywood Thomas.<br />

Our <strong>programme</strong> <strong>notes</strong> are also available to download at bbc.co.uk/now<br />

Family <strong>notes</strong> on tonight’s concert are available from the Orchestra Information Desk.<br />

St David’s Hall, Cardiff Friday 12 October 2012, 7.30pm

<strong>BBC</strong> National Orchestra of Wales<br />

Forthcoming concerts<br />

St David’s Hall, Cardiff<br />

Friday 2 November 2012, 7.30pm<br />

WAGNER Lohengrin – Act 1 Prelude<br />

BRAHMS Violin Concerto<br />

ZEMLINSKY Lyric Symphony<br />

Conductor Jac van Steen<br />

Violin Viviane Hagner<br />

Soprano Elizabeth Atherton<br />

Baritone Roman Trekel<br />

Friday 14 December 2012, 7.30pm<br />

HANDEL Messiah<br />

Conductor François-Xavier Roth<br />

Soprano Susan Gritton<br />

Mezzo-soprano Delphine Galou<br />

Tenor Topi Lehtipuu<br />

Bass Matthew Brook<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> National Chorus of Wales<br />

Friday 25 January 2013, 7.30pm<br />

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5, ‘Emperor’<br />

BRITTEN Spring Symphony<br />

Conductor David Atherton<br />

Piano Paul Lewis<br />

Soprano Elizabeth Atherton<br />

Alto Jennifer Johnston<br />

Tenor Andrew Kennedy<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> National Chorus of Wales<br />

Cardiff Polyphonic Choir<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff Bay<br />

Tuesday 16 October 2012, 2.00pm<br />

PROKOFIEV Symphony-Concerto<br />

VASILY KALINNIKOV Symphony No. 1<br />

Conductor Thomas Søndergård<br />

Cello Andreas Brantelid<br />

Friday 26 October 2012, 7.00pm<br />

CAMBERWELL COMPOSERS’ COLLECTIVE<br />

CHRISTOPHER MAYO The Llano Curve<br />

ANNA MEREDITH Barchan<br />

CHARLIE PIPER Kick up the fire<br />

EMILY HALL Love Songs<br />

MARK BOWDEN Sudden Light<br />

Conductor Andrew G<strong>our</strong>lay<br />

Singer Mara Carlyle<br />

Trombone Donal Bannister<br />

Monday 29 October 2012, 7.30pm<br />

THE PIANO<br />

A gala concert bringing to a close <strong>BBC</strong> Radio 3’s<br />

autumn piano focus. In an evening of piano concertos<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> Hoddinott Hall will feature the virtuosic mastery<br />

of artists including Kathryn Stott and Noriko Ogawa.<br />

Monday 12 November 2012, 7.30pm<br />

ELGAR Overture ‘Cockaigne’ (In London Town)<br />

BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1<br />

RACHMANINOV Symphonic Dances<br />

Conductor David Atherton<br />

Violin Tasmin Little<br />

Tonight’s <strong>programme</strong><br />

A warm welcome to this evening’s concert, a particularly special occasion as it<br />

marks Thomas Søndergård’s debut as Principal Conductor of <strong>BBC</strong> National<br />

Orchestra of Wales. He is particularly renowned in Nordic repertoire so it’s apt<br />

that there should be three strikingly contrasting examples on the menu.<br />

We begin with EXPO <strong>by</strong> the Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg. It’s an<br />

apposite curtain-raiser as he wrote it to mark the start of another auspicious<br />

partnership: that between the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and its Music<br />

Director Alan Gilbert. Lindberg is seen in some circles as the natural successor<br />

to Sibelius, whose Fifth Symphony is one of the masterpieces of the 20th<br />

century and a work whose immediacy belies the struggle the composer faced<br />

in completing it.<br />

Grieg and Richard Strauss were both consummate songwriters, and both were<br />

influenced <strong>by</strong> their singer-wives. Danish soprano Inger Dam-Jensen, a great<br />

fav<strong>our</strong>ite with Cardiff audiences ever since she won the <strong>BBC</strong> Cardiff Singer of<br />

the World, presents a selection of some of their most ravishing creations. And<br />

Strauss returns to take another bow, in his most irrepressible tone-poem,<br />

Till Eulenspiegel.<br />

Introduction<br />

Please turn off all mobile phones and digital watches during the performance.<br />

Try to stifle unavoidable coughs until the normal breaks in the performance.<br />

Photography and recording is not permitted.<br />

2 bbc.co.uk/now<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 3

4<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong> Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

Magnus Lindberg (born 1958)<br />

EXPO (2009)<br />

The speculation had been growing for some time<br />

as to who was going to succeed Lorin Maazel as<br />

chief conductor of the New York Philharmonic.<br />

The names of several grandees of the baton had<br />

been bandied ab<strong>out</strong> when on 18 July 2007 the<br />

announcement was made, a refreshingly farsighted<br />

one: it was to be Alan Gilbert, a native<br />

New Yorker then not yet 40 and, what’s <strong>more</strong>, a<br />

‘son’ of the orchestra – his father had played in<br />

the violins until his retirement and his mother still<br />

does. Gilbert has a reputation as a bold conductor<br />

of contemporary music and before his first<br />

concert as Music Director, which fell on 16<br />

September 2009, Gilbert made it clear that his<br />

<strong>programme</strong>s were going to be less conservative<br />

than those of his immediate predecessors (Lorin<br />

Maazel, Kurt Masur and Zubin Mehta), appointing<br />

Magnus Lindberg as the orchestra’s composer-inresidence.<br />

When EXPO opened that first concert,<br />

the symbolism was clear: Lindberg was only the<br />

third composer, after Bernstein and Copland, to<br />

write a work to open a New York Philharmonic<br />

season.<br />

Lindberg’s <strong>programme</strong> note for the premiere<br />

<strong>out</strong>lined some of the ideas that went into the<br />

piece:<br />

The title is self-explanatory: it’s the exposition of<br />

Alan’s season. I work with extremely strong<br />

contrasts, setting up some contrasts between<br />

super-fast and super-slow music and then a<br />

strange amalgam between these poles. It’s a<br />

piece built on qualities I find so gorgeous in<br />

Alan’s way of making music – absolute technical<br />

and physical straightness, no mystery around the<br />

rational part of it, and then on top of that the<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

highly irrational and mysterious part of how you<br />

actually put music together.<br />

Given the brevity of the piece – around 10<br />

minutes – I thought a pithy word such as ‘EXPO’<br />

would make a fitting title; besides, I like the<br />

sound of the word. A work of any length must<br />

have a trajectory, a sense of direction and logic<br />

ab<strong>out</strong> the way it evolves. I have tried to establish<br />

a musical language to communicate this drama.<br />

As short as EXPO is, there are <strong>more</strong> than 10<br />

tempo markings, resulting in a feeling of great<br />

tension and energy in the orchestra.<br />

EXPO begins <strong>by</strong> establishing Lindberg’s ‘strong<br />

contrasts’: rushing string figuration in the upper<br />

strings which is swiftly set against a stately<br />

chorale-like idea in the brass. The two alternate<br />

briefly and then begin to coalesce – combining two<br />

streams of music in different tempos is a fav<strong>our</strong>ite<br />

Lindberg habit. After a climax marked <strong>by</strong> a lusty,<br />

clodhopping dance from the brass, swirling harp<br />

and violins suggest the play of waves and the<br />

music broadens <strong>out</strong> as in a seascape. At this point<br />

in the score Lindberg indulges in a private nod of<br />

thanks. Just as Shostakovich used the horns to call<br />

<strong>out</strong> the name of an inamorata in his 10th<br />

Symphony, so Lindberg writes a motto into the<br />

score – ‘Alle guten Dinge sind drei’ (all good things<br />

come in threes) – and translates three names into<br />

<strong>notes</strong> which the horns and trumpets call <strong>out</strong>: Zarin<br />

Mehta (president of the New York Philharmonic),<br />

Alan Gilbert and Matías Tarnopolsky (who was<br />

then the orchestra’s vice-president of artistic<br />

planning). The timpani underline the horn<br />

statement and a brief but gorgeous melody<br />

emerges in harmony from the cellos. Fluttering<br />

flutes suggest the Arctic birds of Lindberg’s<br />

compatriot and former teacher Einojuhani<br />

Rautavaara, the rushing strings and chorale of the<br />

opening re-emerge and the music rises to, and<br />

sinks from, another climax; as the strings continue<br />

to eddy, trumpets with cup mutes bring an<br />

American flav<strong>our</strong> to the sound. The clodhopping<br />

dance strides <strong>out</strong> again and is swept into another<br />

climax, scored with astonishing richness – what<br />

seems like an allusion to Strauss’s Also sprach<br />

Zarathustra may not be entirely a coincidence. As<br />

the music calms down, the cello harmonies are<br />

heard again before the strings and woodwind,<br />

capped <strong>by</strong> a piccolo, barrel onwards excitedly.<br />

Lindberg blends his fast and slow tempos one last<br />

time before EXPO settles into a sumptuous<br />

pianissimo chord spread across the entire orchestra<br />

and sinks into silence.<br />

Programme note © Martin Anderson<br />

Martin Anderson writes on music – often on Nordic<br />

and Baltic composers – for a number of publications,<br />

including ‘The Independent’ and ‘Tempo’ in the UK and<br />

‘Fanfare’ in the USA. He also publishes books on music<br />

and releases CDs.<br />

Ab<strong>out</strong> the composer<br />

Over the past decade and a half Magnus<br />

Lindberg’s position as one of the most widely<br />

heard of all contemporary composers has been<br />

reinforced <strong>by</strong> performance after performance; he<br />

is certainly the most popular Finnish composer<br />

since Sibelius. That achievement is the <strong>more</strong><br />

telling when you consider that he made his mark<br />

with large-scale orchestral scores of considerable<br />

complexity.<br />

The piece that first put Lindberg’s name before a<br />

wider international public was his huge, halfh<strong>our</strong>-long<br />

Kraft, for a concertante group of seven<br />

soloists and orchestra: in 1986 it won both the<br />

music prize of the Nordic Cultural Council and an<br />

award from the UNESCO Rostrum of Composers.<br />

But the very Expressionist zeal which brought<br />

Kraft such attention gave Lindberg himself pause<br />

for thought, and he spent some time<br />

reconsidering his musical means. Why, he<br />

wondered, had modern music turned its back on<br />

the directional strength supplied <strong>by</strong> Classical<br />

harmony?<br />

The result was a new inclusiveness in his style,<br />

and the works he has composed since that<br />

Damascene enlightenment, beginning with the<br />

orchestral triptych Kinetics (1988–9), Marea and<br />

Joy (both 1989–90), have combined modernist<br />

col<strong>our</strong> and Classical symphonic strength in a<br />

musical language of ever-increasing<br />

res<strong>our</strong>cefulness and approachability. The sheer<br />

physical impact of Lindberg’s major orchestral<br />

scores accounts for some degree of their<br />

immediate appeal but there’s another factor<br />

involved, something rare in contemporary music<br />

– a sense of fun.<br />

The architecturally informed harmonic thinking<br />

revealed in the Kinetics/Marea/Joy trilogy was<br />

deployed at full strength in what is probably<br />

Lindberg’s most important work to date, the<br />

deeply moving Aura (in memoriam Witold<br />

Lutosławski), composed in 1993–4. Lindberg<br />

describes the piece as a concerto for orchestra<br />

– but with f<strong>our</strong> movements, and at 40 minutes<br />

long, it is a symphony in all but name, and one<br />

possessing a profundity and power that justify<br />

its place downstream from Beethoven, Brahms,<br />

Mahler, Sibelius and the other masters of<br />

symphonic form.<br />

The works since Aura have underlined Lindberg’s<br />

mastery. Another orchestral triptych – Feria<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 5

Programme <strong>notes</strong> Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

(1997), Parada (2001) and Cantigas (1997–9) –<br />

enjoys an electrifying charge of energy. And<br />

Sculpture, written in 2005 to celebrate Frank<br />

Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles,<br />

again demonstrates that sure-footed command of<br />

large-scale symphonic structure, so that the<br />

Classical restraint of the Violin Concerto (2006),<br />

scored for chamber orchestra, surprised many<br />

listeners who <strong>by</strong> now thought they had the<br />

measure of the composer. Seht die Sonne is a<br />

25-minute orchestral triptych commissioned <strong>by</strong><br />

the Berlin Philharmonic in 2007 and given its UK<br />

premiere at the <strong>BBC</strong> Proms the following year.<br />

Three works resulted from Lindberg’s three years<br />

as composer-in-residence with the New York<br />

Philharmonic Orchestra: EXPO (2009), being<br />

heard in this evening’s concert; Al largo (2009–<br />

10), an expansive tone-poem which integrates<br />

fast and slow tempos rather as a seascape<br />

simultaneously presents the capricious play of the<br />

waves and the immense, slow power of the deep;<br />

and a Second Piano Concerto (2011–12), heard for<br />

the first time in May this year and described as a<br />

‘monster’ in The New York Times. Lindberg’s next<br />

big score is a commission from the Royal<br />

Concertgebouw Orchestra, to be heard in January<br />

next year.<br />

Profile © Martin Anderson<br />

<strong>Find</strong> <strong>out</strong> <strong>more</strong><br />

www.boosey.com<br />

Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)<br />

F<strong>our</strong> Songs<br />

Two brown eyes, Op. 5 No. 1 (1864,<br />

orch. Painter)<br />

I love you, Op. 5 No. 3 (1864, orch. Reger)<br />

A swan, Op. 25 No. 2 (1876, orch. Grieg)<br />

Spring, Op. 33 No. 2 (1881, orch. Grieg)<br />

Inger Dam-Jensen soprano<br />

Nina Hagerup seems to have been a singer<br />

possessed of what that wildly entertaining song<br />

parodist Anna Russell described as ‘great artistry<br />

but very little voice’. To be fair, the voice <strong>by</strong> all<br />

accounts was perfectly pretty, but it was the<br />

artistry that inspired the greatest songs of the<br />

man Nina married in 1867, Edvard Grieg.<br />

According to a fellow singer, Nina ‘plumbed the<br />

depths of individual words’, which accorded well<br />

with Grieg’s avowed intention to ‘allow the text<br />

to speak’. He was possessed <strong>by</strong> the lyrics, and his<br />

gift was essentially lyric in miniature, even in the<br />

handful of <strong>more</strong> ambitious constructions such as<br />

the Piano Concerto and the Symphonic Dances. In<br />

smaller forms, such as the works for solo piano<br />

and voice with piano or orchestra, his inspiration<br />

always went straight to the heart of the matter.<br />

Even so, as he told his American biographer:<br />

I don’t think I have a greater talent for<br />

composing songs than for any other musical<br />

genre. Why, then, have songs played such a<br />

prominent role in my music? Quite simply<br />

because I, like other mortals, was (to use<br />

Goethe’s phrase) once in my life endowed with<br />

genius. And that flash of genius was: love. I<br />

loved a young woman with a marvellous voice<br />

and an equally marvellous gift as an interpreter.<br />

This woman became my wife and has remained<br />

my life’s companion to this day. She has been, I<br />

daresay, the only true interpreter of my songs.<br />

It is certainly true that the flame of Grieg’s<br />

inspiration was first fanned in his Op. 5 collection,<br />

Melodies of the Heart, composed in Copenhagen<br />

not long after his betrothal to Nina in 1864 (her<br />

parents disapproved; hence the three-year<br />

engagement). The author is none other than Hans<br />

Christian Andersen and the poems – from which<br />

Grieg selected the happier inspirations – chart<br />

Andersen’s own unrequited adoration of a young<br />

woman named Riborg Voigt. Grieg’s settings were<br />

a gift for his fiancée in a gesture akin to Strauss’s<br />

wedding present for Pauline, and at the tender<br />

age of 21 he hit upon the song for which he is<br />

most famous, ‘Jeg elsker dig’ (‘I love you’).<br />

Discreet chromaticisms in the accompaniment<br />

subtly complement the singer’s <strong>more</strong><br />

straightforward effusions, which build to an<br />

accelerating, operatic intensity in the fivefold<br />

declaration of ‘I love you’. There is only one verse<br />

in the original, a perfect lyric miniature, though a<br />

second was infelicitously added with<strong>out</strong> Grieg’s<br />

approval. ‘Two brown eyes’, again setting<br />

Andersen, is even simpler – a little gem in which<br />

the voice coasts with loving delight over the<br />

tripping accompaniment.<br />

Grieg only orchestrated seven of his 180 or so<br />

songs, and the two examples we hear tonight are<br />

masterpieces. ‘En svane’ (‘A swan’), from the<br />

composer’s only group of Ibsen settings,<br />

combines a characteristic Nordic freshness with a<br />

note of heartache for the bird who sings in death.<br />

The same bittersweet quality informs ‘Våren’<br />

(‘Spring’), perhaps best known as one of the<br />

Elegiac Melodies for string orchestra: it is the<br />

apogee of Grieg’s generous melodic word-setting<br />

and his wife’s ability to plumb the depths of a<br />

poem, each of the verses unfolding logically and<br />

with<strong>out</strong> repetition.<br />

Programme note © David Nice<br />

David Nice is a writer, lecturer and broadcaster on<br />

music who contributes regularly to Radio 3’s ‘CD<br />

Review’ and ‘<strong>BBC</strong> Music Magazine’. The first volume of<br />

his Prokofiev biography was published in 2003 and he<br />

is currently working on the second.<br />

For texts, see page 9<br />

Ab<strong>out</strong> the composer<br />

Well over a century after his death, Edvard<br />

Hagerup Grieg (born 15 June 1843 in Bergen)<br />

remains the foremost of Norwegian composers.<br />

He was also the first composer from the Nordic<br />

countries to win international acclaim. His<br />

surname was actually of Scottish derivation: his<br />

great-grandfather changed his name from Greig<br />

to Grieg when he took Norwegian nationality in<br />

1779. But Grieg’s sense of Norwegian nationality<br />

was increasingly central to his work. Many<br />

melodies presumed to be Norwegian folk songs<br />

were really composed <strong>by</strong> Grieg. In fact, he rarely<br />

used original folk music in his works but he<br />

understood its language, its moods, inflections<br />

and thinking so deeply that creating original ‘folk’<br />

tunes became almost a reflexive action for him.<br />

Initially Grieg was thoroughly schooled in the<br />

Romantic German repertoire. Hearing the teenage<br />

Grieg at the piano, the violinist and composer<br />

6 bbc.co.uk/now<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 7

8<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

Ole Bull persuaded his parents to send him to<br />

the Leipzig Conservatory, where he studied with<br />

the Schumann enthusiast E. F. Wenzel and heard<br />

Schumann’s widow Clara playing her husband’s<br />

Piano Concerto, which left a lasting impression.<br />

But Grieg was unhappy in Leipzig and the strain<br />

probably contributed to an attack of pleurisy in<br />

1860, which left him with lifelong respiratory<br />

problems.<br />

After Leipzig, Grieg studied in Copenhagen with<br />

the Danish composer Niels Gade, on whose<br />

instruction he composed a symphony – which,<br />

however, he later withdrew. Far <strong>more</strong> successful<br />

was the now famous Piano Concerto (1868,<br />

rev. 1907), in which Grieg’s lyrical gifts find<br />

magnificent early flowering. Thereafter he<br />

found worldwide fame chiefly as a miniaturist<br />

– especially in the songs and 10 books of<br />

Lyric Pieces for piano – and in chamber works:<br />

<strong>out</strong>standing among these is the G minor String<br />

Quartet (1877–8), which strongly influenced<br />

Debussy’s only String Quartet.<br />

Grieg’s immersion in Norwegian folk music<br />

began in earnest when he discovered Lindeman’s<br />

pioneering collection Norwegian Mountain<br />

Melodies and befriended Rikard Nordraak<br />

(1842–66), composer of the Norwegian National<br />

Anthem. In 1867 Grieg married his cousin, Nina<br />

Hagerup, a fine singer for whom Grieg composed<br />

many of his songs. Setting the poetry of his<br />

great compatriots Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and<br />

Henrik Ibsen led to productive relationships<br />

with both men, resulting in theatre music for<br />

Bjørnson’s Sigurd Jorsalfar (1872) and the score<br />

for Ibsen’s Peer Gynt (1874–5), one of Grieg’s<br />

crowning achievements. As Grieg’s understanding<br />

of Norwegian folk music deepened, he strove less<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

and less to ‘domesticate’ its astringencies, and<br />

late compositions such as the Slåtter (‘Norwegian<br />

Dances’, 1902–3) for piano can sound strikingly<br />

modern for their time. Years later, the great<br />

Hungarian modernist and ethnomusicologist<br />

Béla Bartók acknowledged Grieg’s importance<br />

as innovator and renewer: ‘He was the first of us<br />

who threw away the German yoke and turned to<br />

the music of his own people’.<br />

Profile © Stephen Johnson<br />

Stephen Johnson was for many years a critic for<br />

both ‘The Independent’ and ‘The Guardian’; he writes<br />

for ‘<strong>BBC</strong> Music Magazine’ and is the author of books<br />

on Bruckner, Mahler and Wagner. He is a regular<br />

presenter of <strong>BBC</strong> Radio 3’s ‘Discovering Music’.<br />

<strong>Find</strong> <strong>out</strong> <strong>more</strong><br />

Anne Sofie von Otter; Bengt Forsberg<br />

(DG 437 521-2)<br />

Grieg Robert Layton (Omnibus)<br />

www.griegsociety.org<br />

1 To brune øjne<br />

To brune Øjne jeg nylig saa,<br />

I dem mit Hjem og min Verden laa.<br />

Der flammed’ Snillet og Barnets Fred;<br />

Jeg glemmer dem aldrig i Evighed!<br />

2 Jeg elsker Dig<br />

Min Tankes Tanke ene du er vorden,<br />

Du er mit Hjaetes første Kjaerlighed.<br />

Jeg elsker Dig som Ingen her på Jorden,<br />

jeg elsker Dig i Tid og Evighed.<br />

Hans Christian Andersen (1805–75)<br />

3 En Svane<br />

Min hvide svane, du stumme, du stille,<br />

Hverken slag eller trille lod sangrøst ane.<br />

Angst beskyttende alfen, som sover,<br />

Altid Iyttende gled du henover,<br />

Men sidste mødet, da eder og øjne<br />

Var lønlige løgne, ja da, da lød det!<br />

I toners føden du slutted din bane.<br />

Du sang i døden; du var dog en svane!<br />

Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906)<br />

Two brown eyes<br />

Two brown eyes I recently saw,<br />

in them my home and my world lay.<br />

There fl<strong>our</strong>ished wisdom and child-like peace;<br />

I will never forget them!<br />

I love you<br />

My thought of thoughts you alone have become,<br />

you are my heart’s first beloved.<br />

I love you as no-one else here on earth.<br />

I love you now and to eternity.<br />

Translations © Beryl Foster<br />

Text<br />

A swan<br />

A white swan, mute and silent,<br />

not a throb nor a warble was heard of y<strong>our</strong> voice.<br />

Anxiously hiding from elves that slumber,<br />

ever listening, you glided on,<br />

but the last meeting, when oaths and eyes<br />

were secret lies – yes then, then it sounded!<br />

In the birth of sound y<strong>our</strong> c<strong>our</strong>se was ended.<br />

You sang in death; you were but a swan!<br />

Please turn the page quietly<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 9

Text<br />

4 Våren<br />

Enno ein Gong fekk eg Vetren at sjå<br />

For Våren å røma;<br />

Heggen med Tre som der Blomar var på<br />

Eg atter så bløma.<br />

Enno ein Gong fekk eg Isen å sjå<br />

Frå Landet at fljota.<br />

Snjoen å bråna og Fossen i Å<br />

Å fyssa og brjota.<br />

Graset det grøne eg enno ein Gong<br />

Fekk skoda med Blomar;<br />

Enno eg høyrde at Vårfuglen song<br />

Mot Sol og mot Sumar.<br />

Eingong eg sjølv i den vårlege Eim,<br />

Som mettar mit Auga,<br />

Eingong eg der vil meg finna ein Heim<br />

Og symjande lauga.<br />

Alt det, som Våren imøte meg bar<br />

Og Blomen, eg plukka,<br />

Federnes Ånder eg trude det var,<br />

Som dansa og sukka.<br />

Derfor eg fann millom Bjørkar og Bar<br />

I Våren ei Gåta;<br />

Derfor det Ljod i den Fløyta eg skar,<br />

Meg tyktes å gråta.<br />

Åsmund Vinje (1818–70)<br />

10 bbc.co.uk/now<br />

Spring<br />

Once again I could see winter<br />

yielding to the spring,<br />

whitethorn with clusters of flowers<br />

I saw blooming again.<br />

Once <strong>more</strong> I saw ice<br />

receding from the earth,<br />

snow melting, waterfalls tumbling in spray,<br />

the river flowing fast.<br />

The green grass once again<br />

I could see clothed in flowers;<br />

again I could hear the spring lark’s song<br />

to sun and summer.<br />

Once <strong>more</strong> I am drawn to the spring vale<br />

that sates my eye’s longing,<br />

to find again a home<br />

where I swim in rapture.<br />

All that the spring bore towards me,<br />

each bloom for the plucking,<br />

the souls of <strong>our</strong> forefathers I seemed to see,<br />

dancing and sighing.<br />

Thus I found, among birches and spruces,<br />

in spring a mystery;<br />

the flute I cut from the reed<br />

seemed to weep.<br />

Translations © Kristina Moseley<br />

Richard Strauss (1864–1949)<br />

Three Songs<br />

Muttertändelei, Op. 43 No. 2 (1899,<br />

orch. 1900)<br />

Meinem Kinde, Op. 37 No. 3 (1897)<br />

Cäcilie, Op. 27 No. 2 (1894, orch. 1897)<br />

Inger Dam-Jensen soprano<br />

Both sets of songs in tonight’s <strong>programme</strong> owe<br />

their special character to the vocal abilities of the<br />

two composers’ wives. The young Richard Strauss<br />

had already written several songs destined to last<br />

before he met capricious Major-General’s daughter<br />

and budding singer Pauline de Ahna in 1887. It was,<br />

however, their marriage in 1894 which launched a<br />

wedding bouquet of songs still among his<br />

best-loved, including ‘Morgen’ (‘Tomorrow’) and<br />

tonight’s ‘Cäcilie’. Pauline won critical plaudits as a<br />

soprano both on the recital platform and in the<br />

opera house, where she achieved notable success<br />

as the heroines of Strauss’s first opera Guntram<br />

and of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, conducted for<br />

the first time in 1892 <strong>by</strong> her husband-to-be.<br />

The fl<strong>our</strong>ishing of Strauss’s song-writing art<br />

coincided with Pauline’s distinguished career,<br />

which she finally relinquished in 1908. Many of his<br />

settings bear in mind her exemplary breath control,<br />

which Strauss was to praise not only in the way<br />

she sang his own music but also in Pamina’s<br />

lament from Mozart’s The Magic Flute and<br />

Elisabeth’s Prayer in Wagner’s Tannhäuser. The long<br />

soprano lines were to continue through<strong>out</strong> his<br />

works long after Pauline’s premature retirement,<br />

through<strong>out</strong> a number of loveable operatic roles –<br />

including the difficult but fundamentally loving<br />

wife in the marriage-comedy Intermezzo with its<br />

thinly veiled portrait of Frau Strauss as Christine<br />

Storch – and, at the end of their long lives, in the<br />

arching phrases of the F<strong>our</strong> Last Songs.<br />

‘Muttertändelei’ (‘Tantalising’) is <strong>by</strong> far the most<br />

familiar among three 1899 settings of ‘old German<br />

poets’, and the only one to be orchestrated the<br />

following year, premiered in that form <strong>by</strong> Pauline. It<br />

belongs to the vein of Bavarian wit and good<br />

hum<strong>our</strong> that Strauss first displayed in his tonepoem<br />

Till Eulenspiegel (which you’ll be able to hear<br />

later tonight) and it also looks forwards to the<br />

mock-epic treatment of the Strausses’ home life in<br />

the Symphonia Domestica. Pauline, perhaps, would<br />

not have gone as far in holding up her ba<strong>by</strong> son<br />

Franz for admiration as this chatterbox mother<br />

does in extolling her paragon infant, but the vocal<br />

writing is as delicious as the woodwind details,<br />

which include the new opening bars for clarinet<br />

and bassoon in the orchestration.<br />

‘Meinem Kinde’ (‘My Child’) is a lulla<strong>by</strong> capturing<br />

the tenderer side of motherhood, keenly<br />

anticipated <strong>by</strong> the Strausses at the time: the song<br />

was written in February 1897; their son Franz was<br />

born in April. The beauty of the song is<br />

heightened <strong>by</strong> the accompanying chamber group<br />

of 10 solo musicians. ‘Cäcilie’ (‘Cecilia’),<br />

orchestrated in the same year as ‘Meinem Kinde’,<br />

belongs to the wedding group of 1894, vintage<br />

Straussian love music at its most ardent.<br />

Programme note © David Nice<br />

For texts, see page 14<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

11

12<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong> Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

Ab<strong>out</strong> the composer<br />

Born in Munich the year before the premiere of<br />

Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde and dying the year<br />

after the composition of Boulez’s Second Piano<br />

Sonata, Richard Strauss had a varied career that<br />

bridged seven turbulent decades. As with Wagner<br />

and Boulez, the young firebrand would eventually<br />

become part of the Establishment he had seemed<br />

keen to overthrow – a rapprochement <strong>more</strong><br />

problematical to us today than his earlier<br />

antagonism. Strauss’s early tone-poems cast aside<br />

the conservative models fav<strong>our</strong>ed <strong>by</strong> his<br />

horn-player father Franz, their programmatic<br />

aspirations col<strong>our</strong>ed with a bold and vivid<br />

orchestral palette. By 1900 this remarkable<br />

sequence of pieces included Don Juan, Death and<br />

Transfiguration, Till Eulenspiegel, Also sprach<br />

Zarathustra, Don Quixote and Ein Heldenleben.<br />

The new century saw Strauss’s energies directed<br />

primarily towards opera, the lurid, nightmarish<br />

worlds of Salome and Elektra serving further to<br />

enhance a well-cultivated notoriety.<br />

Der Rosenkavalier (1909–10) represented a<br />

marked change of tack for Strauss and his<br />

collaborator, Hugo von Hofmannsthal: in place of<br />

some mythic tale of bloodlust and parricide, here<br />

was a farce-cum-lyrical comedy consciously<br />

modelled on Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.<br />

Critical opinion has been fairly harsh towards<br />

much of his later <strong>out</strong>put, at least until the onset<br />

of an extraordinary Indian summer. While<br />

Metamorphosen (1945) and the F<strong>our</strong> Last Songs<br />

(1948) are acknowledged as poignant, valedictory<br />

masterpieces, his intervening works can seem<br />

well-wrought rather than consistently inspired,<br />

content to mine a depleted (and increasingly<br />

anachronistic) seam.<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

On a personal level, too, Strauss has been<br />

attacked for his egotism and insensitivity –<br />

certainly, his association with the Nazi regime<br />

seems ill-judged. But Strauss is best seen as a<br />

product of Imperial Germany for whom the<br />

Weimar Republic was an ineffectual interlude, and<br />

neither his casual anti-Semitic remarks nor his<br />

hostility to democracy makes him a war criminal.<br />

As Otto Klemperer remarked, his reasons for<br />

staying may have been primarily financial –<br />

‘because in Germany there were 56 opera houses,<br />

and in America only two’. Yet, having incurred the<br />

wrath of Goebbels for insisting on the rights of<br />

Stefan Zweig, the Jewish librettist of his Die<br />

schweigsame Frau (1933–4), Strauss wrote a<br />

famously abject letter to Hitler, praising him as<br />

‘the great architect of German social life’.<br />

If Strauss the man seldom seemed overburdened<br />

<strong>by</strong> considerations of good taste, sensitivity and<br />

insight constantly invade his work, not least his<br />

200-odd songs. In his <strong>more</strong> tender moments the<br />

bluff, b<strong>our</strong>geois exterior is left behind. It says<br />

something for him that his exhibitionistically<br />

shrewish wife Pauline pined away and died soon<br />

after their 54-year marriage ended with his death.<br />

Characteristically, Strauss himself once issued his<br />

own testimonial in the most brusque of terms,<br />

telling an orchestra, ‘I may not be a first-rate<br />

composer, but I am a first-class second-rate one.’<br />

Profile <strong>by</strong> David Gutman © <strong>BBC</strong><br />

David Gutman is the author and/or editor of books<br />

on subjects ranging from Prokofiev to John Lennon<br />

and is a regular contributor to ‘Gramophone’. He has<br />

written the Proms Further Listening & Reading <strong>notes</strong><br />

since 1996.<br />

<strong>Find</strong> <strong>out</strong> <strong>more</strong><br />

Inger Dam-Jensen; Malcolm Martineau<br />

(Altara ALT1033)<br />

Richard Strauss: Man, Musician, Enigma<br />

Michael Kennedy (CUP)<br />

www.richardstrauss.at<br />

Player profile<br />

David Haime cello<br />

What first sparked y<strong>our</strong> interest in<br />

performing as a professional cellist?<br />

I studied the cello with Phillip Kent, a former<br />

principal of the <strong>BBC</strong> Welsh Orchestra, and<br />

was first inspired to make music my career<br />

after attending ‘Friday Night is Music Night’<br />

concerts, given <strong>by</strong> the Orchestra in Cardiff’s<br />

City Halls.<br />

What do you enjoy ab<strong>out</strong> being a<br />

professional musician?<br />

Making music with such wonderful<br />

musicians is a thrill. And I have played in<br />

concerts with some amazing soloists and<br />

conductors over these past 34 years.<br />

What has been the most memorable<br />

moment of y<strong>our</strong> career with <strong>BBC</strong> National<br />

Orchestra of Wales?<br />

There have been many! One that rates very<br />

highly is the television recording of a<br />

Tchaikovsky symphony cycle we<br />

performed with Mariss Jansons. All <strong>our</strong><br />

foreign t<strong>our</strong>s bring back great memories,<br />

too: America, Japan, Russia and, most<br />

recently, China.<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 13

Text<br />

1 Muttertändelei<br />

Seht mir doch mein schönes Kind,<br />

Mit den goldnen Zottellöckchen,<br />

Blauen Augen, roten Bäckchen!<br />

Leutchen, habt ihr auch so eins?<br />

Leutchen, nein, ihr habt keins!<br />

Seht mir doch mein susses Kind,<br />

Fetter als ein fettes Schneckchen,<br />

Susser als ein Zuckerweckchen!<br />

Leutchen, habt ihr auch so eins?<br />

Leutchen, nein, ihr habt keins!<br />

Seht mir doch mein holdes Kind,<br />

Nicht zu mürrisch, nicht zu wählig<br />

Immer freundlich, immer fröhlich!<br />

Leutchen, habt ihr auch so eins?<br />

Leutchen, nein, ihr habt keins!<br />

Seht mir doch mein frommes Kind!<br />

Keine bitterbösen Sieben<br />

Würd ihr Mütterchen so lieben.<br />

Leutchen, mochtet ihr so eins?<br />

O, ihr kriegt gewiss nicht meins!<br />

Komm einmal ein Kaufmann her!<br />

Hunderttausend blanke Taler,<br />

Alles Gold der Erde zahl er!<br />

O, er kriegt gewiss nicht meins!<br />

Kauf er sich wo ander eins!<br />

Gottfried August Bürger (1747–94)<br />

14 bbc.co.uk/now<br />

Tantalising<br />

Just look at my lovely child<br />

with her thick golden ringlets,<br />

her blue eyes, red cheeks!<br />

Have you people got one like her?<br />

No, you people, you have not!<br />

Just look at my sweet child,<br />

plumper than a plump snail,<br />

sweeter than a sugar loaf!<br />

Have you people got one like her?<br />

No, you people, you have not!<br />

Just look at my darling child,<br />

not too moody, not too picksome!<br />

Always friendly, always happy!<br />

Have you people got one like her?<br />

No, you people, you have not!<br />

Just look at my good child!<br />

If she were a spiteful shrew,<br />

she wouldn’t love her mother so much.<br />

Would you people like one like her?<br />

Oh, you certainly won’t get mine!<br />

Just let a merchant come along!<br />

A hundred thousand shining guineas,<br />

all the gold on earth, he might pay!<br />

But he certainly won’t get mine!<br />

He can buy one somewhere else!<br />

Translation © William Mann<br />

2 Meinem Kinde<br />

Du schläfst und sachte neig’ ich mich,<br />

Über dein Bettchen und segne dich.<br />

Jeder behutsame Atemzug<br />

Ist ein schweifender Himmelsflug,<br />

Ist ein Suchen welt umher,<br />

Ob nicht dock ein Sternlein wär’,<br />

Wo aus eitel Glanz und Licht<br />

Liebe sich ein Glückskraut bricht,<br />

Das sie geflügelt hernieder trägt<br />

Und dir auf’s weisse Deckchen legs.<br />

Gustav Falke (1853–1916)<br />

3 Cäcilie<br />

Wenn du es wüsstest,<br />

Was träumen heisst von brennenden Küssen,<br />

Von Wandern und Ruhen mit der Geliebten,<br />

Aug’ in Auge,<br />

Und kosend und plaudernd,<br />

Wenn du es wüsstest,<br />

Du neigtest dein Herz!<br />

Wenn du es wüsstest,<br />

Was bangen heisst in einsamen Nächten,<br />

Umschauert vom Sturm, da niemant tröstet<br />

Milden Mundes die kampfmüde Seele,<br />

Wenn du es wüsstest,<br />

Du kämest zu mir.<br />

Wenn du es wüsstest,<br />

Was leben heisst, umhaucht von der Gottheit<br />

Weltschaffendem Atem, zu schweben empor,<br />

Lichtgetragen zu seligen Höhn,<br />

Wenn du es wüsstest,<br />

Du lebtest mit mir!<br />

Heinrich Hart (1855–1906)<br />

My Child<br />

You sleep and softly I bend down<br />

over y<strong>our</strong> cot and bless you.<br />

Every cautious breath I breathe<br />

is a winged flight to heaven,<br />

is a quest far and wide<br />

to see if there is not a star<br />

from whose pure radiance and light<br />

Love could pluck a herb of grace,<br />

that she might carry down on her wing<br />

and lay upon y<strong>our</strong> white coverlet.<br />

Translation © William Mann<br />

Cecilia<br />

If you but knew<br />

what it means to dream of ardent kisses,<br />

of walking and resting with the beloved,<br />

eye to eye,<br />

caressing and chatting.<br />

If you but knew,<br />

y<strong>our</strong> heart would turn to me.<br />

If you but knew<br />

what it means to long in lonely nights,<br />

amid the storm, with no kind words<br />

to console the battle-weary soul –<br />

if you but knew<br />

you would come to me.<br />

If you but knew<br />

what it means to live, touched <strong>by</strong><br />

the godhead’s world-creating breath, to soar aloft,<br />

borne up <strong>by</strong> the light to blessed heights –<br />

if you but knew,<br />

you would live with me.<br />

Translation <strong>by</strong> Gery Bramall<br />

© Decca Music Group Ltd.<br />

Text<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

15

16<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong> Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

Richard Strauss<br />

Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche,<br />

Op. 28 (1894–5)<br />

Till Eulenspiegel was the fifth of Strauss’s<br />

symphonic poems, though he called it something<br />

<strong>more</strong> complicated on the title-page: ‘Till<br />

Eulenspiegel’s merry pranks, after the old rogue’s<br />

tale – in rondo form – set for large orchestra’. The<br />

verbosity was perhaps inspired <strong>by</strong> the antics of<br />

the work’s early 14th-century hero, a notorious<br />

troublemaker who is supposed to have roamed<br />

around northern Germany, both literally and<br />

figuratively upsetting applecarts, then evading<br />

retribution <strong>by</strong> means of a subtle and ready<br />

tongue. Till Eulenspiegel (the surname means<br />

‘owl-mirror’, which might be a corruption of the<br />

French espièglerie – ‘mischief’ – or might simply<br />

be a bit of coarse Low German) is usually depicted<br />

in old prints as a jester with cap and bells but<br />

Strauss’s image is less homely, rougher, <strong>more</strong><br />

alternative. History (or myth) relates that Till died<br />

of the Black Death, whereas Strauss has him<br />

summarily hanged. There is even a marked grave<br />

in the town of Mölln, near Lübeck:<br />

Disen Stein sol nieman erhaben<br />

Hie stat Ulenspiegel begraben.<br />

(Lifting this stone is illegal;<br />

here lies Eulenspiegel.)<br />

Strauss originally intended an opera on the<br />

subject but lost interest in the idea after the<br />

failure of his first opera, Guntram, in May 1894.<br />

Apart from disillusionment with the stage, he<br />

admitted to a difficulty fleshing <strong>out</strong> the main<br />

character, a problem which doesn’t necessarily<br />

arise in an orchestral work. In Till Eulenspiegel, as<br />

in Don Juan, the hero can be a fairly generalised<br />

concept alternating with situations which, <strong>by</strong> their<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

nature, are different until the main character<br />

intrudes on them and messes them up. As Liszt<br />

had shown in his symphonic poems, this is a<br />

handy device for the elaboration of a restricted<br />

amount of material. But, whereas Liszt tended to<br />

confine himself to a limited set of motifs, Strauss,<br />

like Wagner, knew how to invent graphic ideas<br />

that could be worked in well with the themes for<br />

his central character. And it’s his brilliance in this<br />

department that makes Till Eulenspiegel such a<br />

spectacular example of musical visualisation: a<br />

medieval woodcut turned into a Romantic<br />

tone-poem.<br />

The Till themes are easily noticed and tracked.<br />

The brief introduction supplies the first, on violins<br />

(‘Once upon a time …’), and the second follows<br />

at once on solo horn. These two themes are<br />

developed <strong>by</strong> Strauss through<strong>out</strong> the piece in a<br />

bewildering variety of guises and with fantastic<br />

virtuosity. As for his hero’s escapades, Strauss<br />

never referenced them in print but did mark up his<br />

own score. At the end of the initial exposition, Till<br />

rides through the market, upsetting stalls and<br />

stallkeepers, then escapes dressed as a priest<br />

(slower theme on violas, clarinet and bassoons);<br />

next he falls in love (lyrical development of his<br />

own themes), is jilted, to his fury (sudden <strong>out</strong>burst<br />

of his horn theme, triple forte); then, in what<br />

amounts to the second rondo episode, engages in<br />

an increasingly confused debate with some<br />

learned professors (grumpy low woodwind).<br />

Eventually Till thumbs his nose at these pedants<br />

and nips away, whistling a merry tune.<br />

Strauss now moves into a recapitulation, starting<br />

again with the main horn solo, then elaborating<br />

the material in an ecstasy of miscreance until the<br />

inevitable happens: Till is caught, tried and<br />

condemned to death – music so Straussianly<br />

graphic that it needs no explanation. A brief<br />

Epilogue extends the ‘Once upon a time …’ into a<br />

‘they all lived happily ever after’ – including Till<br />

himself, whose spirit, the final bars prove, will<br />

never die.<br />

Programme note © Stephen Walsh<br />

Stephen Walsh is the author of a major two-volume<br />

biography of Stravinsky and holds a Chair in Music at<br />

Cardiff University.<br />

<strong>Find</strong> <strong>out</strong> <strong>more</strong><br />

Dresden Staatskapelle/Rudolf Kempe<br />

(EMI 9187452)<br />

Interval: 20 minutes<br />

Jean Sibelius (1865–1957)<br />

Symphony No. 5 in E flat major,<br />

Op. 82 (1915, rev. 1916, 1919)<br />

1 Tempo molto moderato – Allegro<br />

moderato (ma poco a poco stretto) –<br />

Presto – Più presto<br />

2 Andante mosso, quasi allegretto<br />

3 Allegro molto<br />

Through<strong>out</strong> his working life, Sibelius kept diaries.<br />

For anyone interested in his music they are<br />

packed with revelations. The years 1914–15 –<br />

the period when Sibelius began making<br />

extensive sketches for the Fifth Symphony –<br />

are especially interesting. Sibelius writes ab<strong>out</strong><br />

how he composes:<br />

Arrangement of the themes. This important<br />

task, which fascinates me in a mysterious way.<br />

It’s as if God the Father had thrown down the<br />

tiles of a mosaic from heaven’s floor and asked<br />

me to determine what kind of picture it was.<br />

And he reflects on the broader meaning of<br />

his symphonies:<br />

To me they are confessions of faith from the<br />

different periods of my life. And from this it<br />

follows that my symphonies are all<br />

so different.<br />

Then, in an entry dated 21 April 1915, Sibelius<br />

relates one of the new symphony’s themes to<br />

an event which stirred him to the core:<br />

Today at ten to eleven I saw 16 swans. One<br />

of my greatest experiences! Lord God, what<br />

beauty! They circled over me for a long time.<br />

Disappeared into the solar haze like a gleaming,<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 17

18<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

silver ribbon. Their call the same woodwind<br />

type as that of cranes, but with<strong>out</strong> tremolo.<br />

The swan-call closer to the trumpet …<br />

A low-pitched refrain reminiscent of a small<br />

child crying. Nature mysticism and life’s angst!<br />

The Fifth Symphony’s finale-theme: legato in<br />

the trumpets!<br />

It took Sibelius another f<strong>our</strong> years of hard work<br />

(including two extensive revisions) to bring the<br />

Fifth Symphony to its final form. The musical<br />

tiles had to be moved around again and again<br />

before Sibelius was satisfied he could see the<br />

overall picture clearly. But one important feature<br />

is common to all three versions of the symphony.<br />

That finale theme – which Sibelius continued to<br />

refer to as his ‘Swan Hymn’ – doesn’t actually<br />

appear on the trumpets until near the end of the<br />

symphony, where it is marked nobile (‘noble’).<br />

It heralds the beginning of a long, arduous<br />

crescendo, clearly evoking ‘life’s angst’ in grinding<br />

dissonances and hard-edged orchestration.<br />

There are other passages in the Fifth Symphony<br />

where shadows fall across the music – the<br />

sombre, plaintive bassoon solo at the heart of<br />

the first movement (emerging through nervous,<br />

whispering string figures) is another point at<br />

which the music seems to look back to the pain<br />

and dark introspection of the F<strong>our</strong>th Symphony<br />

(1910–11). Certainly the Fifth isn’t all solar<br />

glory. But that only makes the final triumphant<br />

emergence of the ‘Swan Hymn’ all the <strong>more</strong><br />

convincing: the symphony has had to struggle<br />

to achieve it.<br />

A quiet, pregnant horn motif sets the first<br />

movement (Tempo molto moderato) on its<br />

c<strong>our</strong>se; this is the musical seed from which the<br />

music grows in two huge crescendo waves, each<br />

one topped <strong>by</strong> a blazing two-note trumpet-<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

call. Then the splend<strong>our</strong> fades and we hear the<br />

long, plaintive bassoon solo mentioned above.<br />

For a while, the music seems to have lost its<br />

direction. In the symphony’s first version (1915)<br />

the movement petered <strong>out</strong> soon after this, to be<br />

followed <strong>by</strong> a faster scherzo. But then Sibelius<br />

was struck <strong>by</strong> a stunning new idea – why not<br />

make the scherzo emerge from the Tempo molto<br />

moderato? The result is one of the most gripping<br />

transitions in all symphonic music. It begins with<br />

another elemental crescendo; the original horn<br />

motif shines <strong>out</strong> on trumpets; then – almost<br />

imperceptibly at first – the tempo begins to<br />

quicken. It goes on getting faster and faster;<br />

<strong>by</strong> the time we arrive at the Più presto closing<br />

pages it’s hurtling forwards with tremendous<br />

energy – the nearest thing in music to a depiction<br />

of white-water rafting. It’s hard to believe that<br />

this apparently seamless organic process wasn’t<br />

conceived in a single inspiration – harder still<br />

to accept that it could have been achieved <strong>by</strong><br />

moving around and exchanging musical ‘tiles’.<br />

At first, the next movement (Andante mosso,<br />

quasi allegretto) appears to offer a relaxing<br />

contrast. Broadly speaking, it is a set of free<br />

variations on a folk-like theme heard at the<br />

beginning (plucked strings and flutes). But things<br />

are going on under that seemingly calm surface,<br />

creating tensions which emerge in troubled<br />

string tremolos or in the brief but menacing brass<br />

crescendos towards the close.<br />

The tension is released as action in the finale<br />

(Allegro molto), which begins as a rapid airborne<br />

dance for high strings. This sweeps on into the<br />

first appearance of the ‘Swan Hymn’ (swinging<br />

horn figures and a chant-like melody for high<br />

woodwind – <strong>more</strong> bird-cries, perhaps). The<br />

whole process is repeated, but with telling<br />

variations: for example, the ‘Swan Hymn’ now<br />

appears in a different key, on woodwind and<br />

muted strings. Then the tempo drops and the<br />

mood becomes tense and expectant – until the<br />

‘Swan Hymn’ returns quietly but radiantly on<br />

trumpets, initiating the long final crescendo. For<br />

a moment, ‘life’s angst’ seems to prevail, but at<br />

last the first swinging phrase of the ‘Swan Hymn’<br />

re-emerges in full orchestral splend<strong>our</strong>. The end is<br />

remarkable: six sledgehammer chords separated<br />

<strong>by</strong> long silences – the music seems to hold its<br />

breath; then, suddenly, almost brusquely, Sibelius<br />

brings the symphony to a close.<br />

Programme note <strong>by</strong> Stephen Johnson © <strong>BBC</strong><br />

Ab<strong>out</strong> the composer<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

Sibelius was born in 1865, in the provincial<br />

Finnish town of Hämeenlinna (ab<strong>out</strong> 60 miles<br />

north of Helsinki), the son of an army doctor and<br />

his music-loving wife. His parents, like most<br />

educated Finns of the time, were Swedishspeakers.<br />

But 11-year-old ‘Janne’ went to a<br />

Finnish-speaking grammar school, where he<br />

learnt the language of most of his countrymen.<br />

As a child he dreamt of becoming a virtuoso<br />

violinist but during his student years in Helsinki he<br />

began to concentrate <strong>more</strong> on composing. He<br />

initially wrote chamber music, before two years<br />

of study in Berlin and Vienna (1889–91)<br />

dramatically revealed to him the potential of the<br />

orchestra. In 1892 Sibelius completed his<br />

five-movement choral symphony Kullervo, based<br />

on a text from the Kalevala, the Finnish national<br />

folk epic. Kullervo’s power and originality revealed<br />

an exceptional command of symphonic form<br />

combined with an uncanny ability to evoke the<br />

northern landscape.<br />

During the 1890s, ‘The Swan of Tuonela’ and<br />

‘Lemminkäinen’s Return’ (two movements from<br />

the f<strong>our</strong> Lemminkäinen Legends, 1893–5)<br />

confirmed Sibelius’s reputation and began to<br />

make his name abroad. The first two symphonies<br />

were followed <strong>by</strong> a sequence of mature<br />

masterpieces, including a Third Symphony (1907)<br />

and the symphonic poems Pohjola’s Daughter<br />

(1905–6) and Night Ride and Sunrise (1908).<br />

Sibelius now began to travel widely, conducting<br />

his music to growing acclaim.<br />

The onset of suspected throat cancer in 1908,<br />

though successfully treated, brought ab<strong>out</strong> a darker<br />

mood that influenced the austere F<strong>our</strong>th<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 19

20<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

Symphony (1910–11). Marooned in Finland <strong>by</strong> the<br />

First World War, Sibelius completed the third and<br />

last version of his Fifth Symphony in 1919. After<br />

this came the Sixth (1923) and Seventh Symphonies<br />

(1924), a large score of incidental music for<br />

Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1925) and the<br />

symphonic poem Tapiola (1926). But then followed<br />

virtual silence, although he lived for another 30<br />

years. He wrote an Eighth Symphony, but later<br />

destroyed it.<br />

Sibelius’s magnitude as a symphonist tends to<br />

overshadow his mastery of other musical forms.<br />

His achievements in the realm of the symphonic<br />

poem were possibly even greater. He excelled,<br />

too, as a song and choral composer and in lighter<br />

musical genres, including music for the theatre.<br />

He composed Finlandia in 1899 to accompany a<br />

display of patriotic tableaux, at a time when his<br />

country’s desire to break free of Russian imperial<br />

domination had reached fever pitch. The work<br />

has remained Finland’s unofficial national anthem<br />

ever since.<br />

Profile <strong>by</strong> Malcolm Hayes © <strong>BBC</strong><br />

Malcolm Hayes is a composer, writer, broadcaster<br />

and music j<strong>our</strong>nalist. He contributes regularly to<br />

‘<strong>BBC</strong> Music Magazine’ and recently completed a<br />

book on Liszt. He is currently working on a biography<br />

of Sibelius.<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

<strong>Find</strong> <strong>out</strong> <strong>more</strong><br />

Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä<br />

(BIS CD863)<br />

Sibelius Robert Layton (OUP)<br />

www.fimic.fi/sibelius<br />

Orchestra Merchandise<br />

Programme <strong>notes</strong><br />

We have a variety of merchandise available<br />

to purchase today from the Orchestra<br />

Information Desk. These include:<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> National Orchestra and Chorus<br />

of Wales – A History Peter Reynolds<br />

£9.99<br />

Limited edition framed<br />

photo art <strong>by</strong> Chris Stock<br />

£50/£65<br />

Child T-Shirt<br />

Black/Burgundy Ages 7–8 & 9–11<br />

£8<br />

Adult T-Shirt<br />

Black/Burgundy S, M, L & XL<br />

£10<br />

Mug<br />

£6<br />

Souvenir Pin Badge<br />

£2<br />

Souvenir Pen<br />

£1.50<br />

We also have a selection of recordings <strong>by</strong><br />

<strong>BBC</strong> National Orchestra of Wales available.<br />

Prices vary: please ask at the Orchestra<br />

Information Desk for further details.<br />

bbc.co.uk/now 21

Bjarke Johansen<br />

Biographies<br />

Thomas Søndergård<br />

conductor<br />

At the start of this season,<br />

Danish conductor Thomas<br />

Søndergård became Principal<br />

Conductor of <strong>BBC</strong> National<br />

Orchestra of Wales and<br />

Principal Guest Conductor of<br />

the Royal Scottish National<br />

Orchestra. He was Principal<br />

Conductor and Musical<br />

Advisor of the Norwegian Radio Orchestra from 2009<br />

to 2012.<br />

Highlights this season include debuts with the Seattle<br />

Symphony and Luxemb<strong>our</strong>g Philharmonic orchestras,<br />

appearances at the Royal Danish Opera (Janá∂ek’s The<br />

Cunning Little Vixen) and the Royal Swedish Opera<br />

(Turandot), a European t<strong>our</strong> with the Junge Deutsche<br />

Philharmonie and returns to the Tivoli Festival and the<br />

Toulouse Capitole, Oslo Philharmonic and Stavanger<br />

Symphony orchestras.<br />

Highlights of recent seasons include debuts with the<br />

Brussels Philharmonic and <strong>BBC</strong>, Houston and<br />

Trondheim Symphony orchestras and return visits to the<br />

Rotterdam and Royal Stockholm Philharmonic<br />

orchestras, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Danish<br />

National and Swedish Radio Symphony orchestras and<br />

the National Arts Centre Orchestra, Ottawa.<br />

Admired for his interpretations of Scandinavian<br />

contemporary repertoire, his discography includes a<br />

number of symphonic scores. His recording of Sibelius<br />

and Prokofiev violin concertos with Vilde Frang was<br />

widely acclaimed. His most recent disc is of Poul<br />

Ruders’s Second Piano Concerto.<br />

Last year he was awarded the Foundation Prize <strong>by</strong><br />

Queen Ingrid for services to Music in Denmark.<br />

22 bbc.co.uk/now<br />

Isak Hoffmeyer<br />

Inger Dam-Jensen<br />

soprano<br />

Danish soprano Inger<br />

Dam-Jensen first came to<br />

international attention when<br />

she won <strong>BBC</strong> Cardiff Singer of<br />

the World in 1993. She has<br />

since established herself as a<br />

leading performer in concert<br />

and on the operatic stage.<br />

Her core repertoire focuses on the Romantic period,<br />

ranging from Beethoven via Brahms to Mahler and<br />

Richard Strauss. She has performed with leading<br />

orchestras around the world, including the New York<br />

and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic orchestras,<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra, Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano<br />

Giuseppe Verdi, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin<br />

and the Danish National Radio, Malmö and Tivoli<br />

Symphony orchestras. Among the many notable<br />

conductors with whom she has worked are Christoph<br />

von Dohnányi, Sir Colin Davis, Xian Zhang, James<br />

Conlon, Edo de Waart, Thomas Dausgaard, Herbert<br />

Blomstedt, Jesús López-Cobos, Vladimir Ashkenazy,<br />

Ernest Martínez-Izquierdo, Claus Peter Flor, Bernard<br />

Haitink and Vassily Sinaisky.<br />

Her operatic repertoire encompasses Handel, Mozart,<br />

Berlioz, Puccini, Richard Strauss, Thomas, Donizetti,<br />

Verdi, Bellini, Wagner and Bizet and she has sung in the<br />

major houses of Europe, including for the Royal Opera,<br />

Covent Garden, Opéra de Paris, Geneva Opera and<br />

Royal Danish Opera.<br />

Inger Dam-Jensen’s discography includes Grieg’s Peer<br />

Gynt, Handel’s Solomon, Brahms’s A German Requiem<br />

and songs <strong>by</strong> Nielsen and Richard Strauss.<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> National<br />

Orchestra of Wales<br />

The <strong>BBC</strong> National Orchestra of Wales occupies a special<br />

role as both a national and broadcasting orchestra,<br />

acclaimed not only for the quality of its performances<br />

but also for its importance within its own community.<br />

The work of <strong>BBC</strong> National Orchestra and Chorus of<br />

Wales is supported <strong>by</strong> the Arts Council of Wales.<br />

In September Thomas Søndergård started in his post of<br />

Principal Conductor, for an initial term of f<strong>our</strong> years. He<br />

joins the formidable conducting team of Principal Guest<br />

Conductor Jac van Steen, Associate Guest Conductor<br />

François-Xavier Roth and Conductor Laureate Tadaaki<br />

Otaka with whom the Orchestra has won considerable<br />

critical and audience acclaim over recent years. As well<br />

as an <strong>out</strong>standing ability to refresh core repertoire, the<br />

Orchestra is proud of its adventurous programming and<br />

continuously demonstrates artistic excellence in new or<br />

rarely performed works. As part of this commitment to<br />

contemporary music, the Orchestra appointed Mark<br />

Bowden as Resident Composer in June 2011.<br />

It is Orchestra-in-Residence at St David’s Hall, Cardiff,<br />

and also presents a concert series at the Brangwyn Hall,<br />

Swansea. As well as international t<strong>our</strong>ing, it is in demand<br />

at major UK festivals and performs every year at the <strong>BBC</strong><br />

Proms and biennially at the <strong>BBC</strong> Cardiff Singer of the<br />

World. Education and Community Outreach is also<br />

integral to its musical life and the department has been<br />

challenging conventions for nearly 15 years, taking the<br />

Orchestra’s work into schools, workplaces and<br />

communities.<br />

Based at its state-of-the-art recording and rehearsal<br />

venue in <strong>BBC</strong> Hoddinott Hall at Wales Millennium<br />

Centre, Cardiff Bay, the Orchestra broadcasts regularly<br />

for radio and television. Its discography includes Havergal<br />

Brian’s ‘Gothic’ Symphony and David Matthews’s Second<br />

and Sixth Symphonies, which won a 2011 <strong>BBC</strong> Music<br />

Magazine Award.<br />

Biographies<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

23

24<br />

Orchestra list<br />

<strong>BBC</strong> National Orchestra of Wales<br />

Patron<br />

HRH The Prince of Wales kg kt pc gcb<br />

Principal Conductor<br />

Thomas Søndergård<br />

Principal Guest Conductor<br />

Jac van Steen<br />

Associate Guest Conductor<br />

François-Xavier Roth<br />

Conductor Laureate<br />

Tadaaki Otaka cbe<br />

Composer-in-Association<br />

Simon Holt<br />

Resident Composer<br />

Mark Bowden<br />

First Violins<br />

Lesley Hatfield<br />

Leader<br />

Nick Whiting<br />

Associate Leader<br />

Carl Dar<strong>by</strong> #<br />

Gwenllian Hâf<br />

Richards<br />

Terry Porteus<br />

Suzanne Casey<br />

Richard Newington<br />

Paul Mann<br />

Gary George-Veale<br />

Robert Bird<br />

Carmel Barber<br />

Kerry Gordon-Smith<br />

Emilie Godden<br />

Anna Cleworth<br />

Elin Edwards<br />

Elizabeth Whittam<br />

Second Violins<br />

Naomi Thomas *<br />

Jane Sinclair #<br />

Ros Butler<br />

Sheila Smith<br />

Vickie Ringguth<br />

Joseph Williams<br />

Michael Topping<br />

Margot Leadbeater<br />

Katherine Miller<br />

Beverley Wescott<br />

Debbie Frost<br />

Nicolas White<br />

Roussanka<br />

Karatchivieva<br />

Jane West<br />

Violas<br />

Göran Fröst *<br />

Alex Thorndike #<br />

Martin Schaefer<br />

Peter Taylor<br />

David McKelvay<br />

Sarah Chapman<br />

James Drummond<br />

Ania Leadbeater<br />

Robert Gibbons<br />

Catherine Palmer<br />

Laura Sinnerton<br />

Charles Cross<br />

Cellos<br />

John Senter *<br />

Keith Hewitt #<br />

Hetty Snell<br />

Sandy Bartai<br />

Margaret Downie<br />

David Haime<br />

Carolyn Hewitt<br />

Kathryn Harris<br />

Sarah Bowler<br />

Jacqueline Phillips<br />

Double Basses<br />

David Stark ‡<br />

David Ayre<br />

Christopher Wescott<br />

William<br />

Graham-White<br />

Richard Gibbons<br />

Tim Older<br />

Claire Whitson<br />

Neil Watson<br />

Flutes<br />

Matthew<br />

Featherstone †<br />

Eilidh Gillespie<br />

Elizabeth May<br />

Eva Stewart<br />

Piccolo<br />

Eva Stewart<br />

Oboes<br />

David Cowley *<br />

Amy McKean<br />

Gillian Taylor<br />

Sarah-Jayne<br />

Porsmoguer<br />

Cor anglais<br />

Sarah-Jayne<br />

Porsmoguer<br />

Clarinets<br />

Robert Plane *<br />

John Cooper<br />

Mark Simmons<br />

Bass Clarinet<br />

Lenny Sayers †<br />

Bassoons<br />

Jarosπaw<br />

Augustyniak *<br />

Martin Bowen<br />

Joanna Shewan<br />

David Buckland<br />

Contrabassoon<br />

David Buckland †<br />

Horns<br />

Tim Thorpe *<br />

Irene Williamson<br />

Ian Fisher †<br />

William Haskins<br />

Neil Shewan<br />

Trumpets<br />

Philippe Schartz *<br />

Adrian Williams<br />

Matthew Williams<br />

Trombones<br />

Donal Bannister *<br />

Andy Connington<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Darren Smith †<br />

Tuba<br />

Daniel Trodden †<br />

Timpani<br />

Steve Barnard *<br />

Percussion<br />

Chris Stock *<br />

Mark Walker †<br />

Harp<br />

Valerie<br />

Aldrich-Smith †<br />

* Section Principal<br />

† Principal<br />

‡ Guest Principal<br />

# Assistant Principal<br />

Director<br />

David Murray<br />

Orchestra Manager<br />

Byron Jenkins<br />

Assistant to Director<br />

and Orchestra<br />

Manager<br />

Bethan Everton<br />

Assistant Orchestra<br />

Manager<br />

Charlotte Sandford<br />

Orchestral<br />

Coordinator<br />

Andy Farquharson<br />

Music Librarian<br />

Christopher Painter<br />

Stage Manager<br />

Andrew Smith<br />

Transport Manager<br />

Mark Terrell<br />

Senior Producer<br />

Tim Thorne<br />

Programme produced <strong>by</strong> <strong>BBC</strong> Proms Publications. Welsh translation <strong>by</strong> Annes Gruffydd.<br />

bbc.co.uk/now<br />

Artists and Concerts<br />

Administrator<br />

Victoria Massocchi<br />

Broadcast Assistant<br />

Callum Thomson<br />

Marketing Manager<br />

Sarah Horner<br />

Assistant Marketing<br />

Manager<br />

Jodi Bennett<br />

Communications<br />

Officer<br />

David Hopkins<br />

Marketing and<br />

Publicity Assistant<br />

Anwen Locke<br />

Audience Line<br />

Operators<br />

Nerys Lloyd-Evans<br />

Margarita Felices<br />

Phillippa Scammell<br />

Education and<br />

Community Manager<br />

Suzanne Hay<br />

Education and<br />

Community<br />

Assistant<br />

Andy Everton<br />

Chorus Manager<br />

Osian Rowlands<br />

Senior Audio<br />

Supervisor<br />

Huw Thomas<br />

Business and Finance<br />

Manager<br />

Chris Rogers