pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

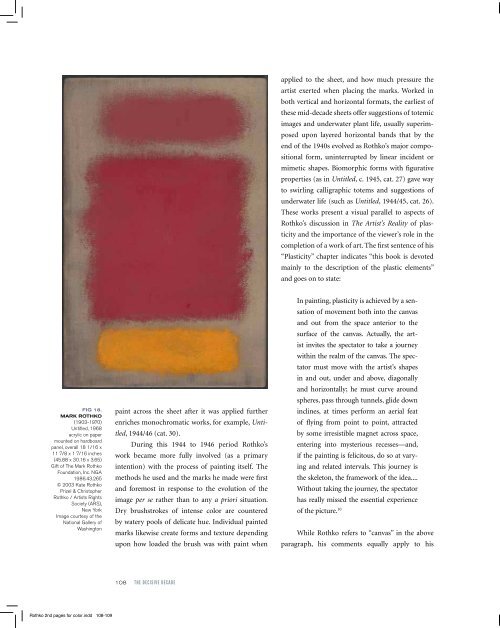

fig 18.<br />

Mark rothko<br />

(1903-1970)<br />

Untitled, 1968<br />

acrylic on paper<br />

mounted on hardboard<br />

panel, overall 18 1/16 x<br />

11 7/8 x 1 7/16 inches<br />

(45.88 x 30.16 x 3.65)<br />

Gift of The Mark Rothko<br />

Foundation, Inc. NGA<br />

1986.43.265<br />

© 2003 Kate Rothko<br />

Prizel & Christopher<br />

Rothko / Artists Rights<br />

Society (ARS),<br />

New York<br />

Image courtesy of the<br />

National Gallery of<br />

Washington<br />

paint across the sheet after it was applied further<br />

enriches monochromatic works, for example, Untitled,<br />

1944/46 (cat. 30).<br />

During this 1944 to 1946 period Rothko’s<br />

work became more fully involved (as a primary<br />

intention) with the process of painting itself. The<br />

methods he used and the marks he made were first<br />

and foremost in response to the evolution of the<br />

image per se rather than to any a priori situation.<br />

Dry brushstrokes of intense color are countered<br />

by watery pools of delicate hue. Individual painted<br />

marks likewise create forms and texture depending<br />

upon how loaded the brush was with paint when<br />

applied to the sheet, and how much pressure the<br />

artist exerted when placing the marks. Worked in<br />

both vertical and horizontal formats, the earliest of<br />

these mid-decade sheets offer suggestions of totemic<br />

images and underwater plant life, usually superimposed<br />

upon layered horizontal bands that by the<br />

end of the 1940s evolved as Rothko’s major compositional<br />

form, uninterrupted by linear incident or<br />

mimetic shapes. Biomorphic forms with figurative<br />

properties (as in Untitled, c. 1945, cat. 27) gave way<br />

to swirling calligraphic totems and suggestions of<br />

underwater life (such as Untitled, 1944/45, cat. 26).<br />

These works present a visual parallel to aspects of<br />

Rothko’s discussion in The Artist’s Reality of plasticity<br />

and the importance of the viewer’s role in the<br />

completion of a work of art. The first sentence of his<br />

“Plasticity” chapter indicates “this book is devoted<br />

mainly to the description of the plastic elements”<br />

and goes on to state:<br />

In painting, plasticity is achieved by a sensation<br />

of movement both into the canvas<br />

and out from the space anterior to the<br />

surface of the canvas. Actually, the artist<br />

invites the spectator to take a journey<br />

within the realm of the canvas. The spectator<br />

must move with the artist’s shapes<br />

in and out, under and above, diagonally<br />

and horizontally; he must curve around<br />

spheres, pass through tunnels, glide down<br />

inclines, at times perform an aerial feat<br />

of flying from point to point, attracted<br />

by some irresistible magnet across space,<br />

entering into mysterious recesses—and,<br />

if the painting is felicitous, do so at varying<br />

and related intervals. This journey is<br />

the skeleton, the framework of the idea....<br />

Without taking the journey, the spectator<br />

has really missed the essential experience<br />

of the picture. 10<br />

While Rothko refers to “canvas” in the above<br />

paragraph, his comments equally apply to his<br />

paintings on paper from these years, which tend to<br />

employ multiple media although transparent watercolor<br />

is primary among the layered hues. Opaque<br />

watercolor touches follow sparingly, and thus function<br />

as focal points within the fields, setting up<br />

a rich contrast to Rothko’s magical line, directly<br />

drawn at first in both black and color inks, but<br />

incised as scraffito increasingly as the ideas evolve,<br />

functioning with authority as rhythm, pattern, edge,<br />

direction, interruption. The ambition of these middecade<br />

watercolors expanded his approach to layering<br />

veils of paint that eventually claimed primacy in<br />

his work.<br />

Central to Rothko’s paintings on paper is the<br />

white of the sheet as it glows through the transparent<br />

and translucent washes the artist applied in diverse<br />

directions, using many different sizes of brushes, and<br />

varying his hand pressure, together to create spatial<br />

diversity within the field. Additionally, opaque white<br />

used independently and in admixtures of various<br />

hues adds density that transparent watercolor generally<br />

defies. As paintings conservator Dana Cranmer<br />

has observed, “during this period, a remarkable symbiosis<br />

occurred between the watercolors and the oils.<br />

Rothko approached the canvas support much as he<br />

did the white paper support of the watercolor.” 11 As<br />

part of his process of applying paint, Rothko increasingly<br />

incorporated rubbing and blotting methods<br />

that provided subtle gradations to the hues. On paper<br />

these actions alter the manufactured surfaces of the<br />

sheets and, thus, the ways in which they subsequently<br />

respond to and carry the paint. Rothko rubbed or<br />

incised with such vehemence at times that he broke<br />

through the sheet entirely.<br />

In early 1946, Rothko’s first exhibition since<br />

1933 comprising solely works on paper was held at<br />

the Mortimer Brandt Gallery in Manhattan. Eighteen<br />

of his mid-1940s watercolors were on view,<br />

many of which were highly enough admired to be<br />

sold during the course of the show. Starting the<br />

following year and for much of the rest of his life,<br />

Rothko’s attention was more focused on canvas than<br />

on paper. But on paper as well as on canvas, thinly<br />

applied layers of paint create zones of color; and<br />

works on the two substrates differ from the other<br />

primarily because of differences in these surfaces<br />

and the responsiveness of materials to their very different<br />

properties, and not in his handling of them.<br />

Size is perhaps the one major delineator—his classic<br />

canvases reach dimensions impossible even with the<br />

largest rolls of paper available at that time (fig. 18). 12<br />

The importance of paper to Rothko’s oeuvre<br />

lasted well beyond the 1940s. What have come to be<br />

viewed as his classic compositions—two, three, or<br />

108 the Decisive DecaDe chapter 109<br />

fig 19.<br />

Mark rothko<br />

(1903-1970)<br />

Untitled, 1969<br />

acrylic on paper, sheet:<br />

71 ¾ x 42 7/16 inches<br />

(182.3 x 107.8)<br />

Gift of The Mark Rothko<br />

Foundation, Inc. NGA<br />

1986.43.278<br />

© 2003 Kate Rothko<br />

Prizel & Christopher<br />

Rothko / Artists Rights<br />

Society (ARS),<br />

New York<br />

Image courtesy of the<br />

National Gallery of<br />

Washington<br />

Rothko 2nd pages for color.indd 108-109 3/2/12 5:22 PM

![01 -[BE/INT-2] 2 KOL +UITGEV+ - exhibitions international](https://img.yumpu.com/19621858/1/184x260/01-be-int-2-2-kol-uitgev-exhibitions-international.jpg?quality=85)